Abstract

Objective To examine whether the introduction of payment by results (a fixed tariff case mix based payment system) was associated with changes in key outcome variables measuring volume, cost, and quality of care between 2003/4 and 2005/6.

Setting Acute care hospitals in England.

Design Difference-in-differences analysis (using a control group created from trusts in England and providers in Scotland not implementing payment by results in the relevant years); retrospective analysis of patient level secondary data with fixed effects models.

Data sources English hospital episode statistics and Scottish morbidity records for 2002/3 to 2005/6.

Main outcome measures Changes in length of stay and proportion of day case admissions as a proxy for unit cost; growth in number of spells to measure increases in output; and changes in in-hospital mortality, 30 day post-surgical mortality, and emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture as measures of impact on quality of care.

Results Length of stay fell more quickly and the proportion of day cases increased more quickly where payment by results was implemented, suggesting a reduction in the unit costs of care associated with payment by results. Some evidence of an association between the introduction of payment by results and growth in acute hospital activity was found. Little measurable change occurred in the quality of care indicators used in this study that can be attributed to the introduction of payment by results.

Conclusion Reductions in unit costs may have been achieved without detrimental impact on the quality of care, at least in as far as these are measured by the proxy variables used in this study.

Introduction

In April 2002 the Department of Health in England outlined plans to introduce a new system of financing hospitals, called “payment by results.”1 The system marked a fundamental change in the way in which hospitals in England were paid for the services they provide. In common with many other healthcare systems, payment by results uses a fixed price system that makes a direct link between a hospital’s income and the number and case mix of patients treated.2 Payment by results was motivated by policy objectives to increase efficiency, volume of activity, and quality of care in English NHS hospitals. This paper presents the findings of the first extensive quantitative empirical analysis of the effects of the policy in its first years of implementation.

Under payment by results, prices (or tariffs) for hospital care are defined in terms of healthcare resource group (HRG) spells of stay in hospital. A spell of activity is a hospital stay from admission to discharge and is a measure of the hospital’s output. An HRG code is assigned to each spell of activity.

The tariff system has various characteristics that shape the incentives of the system. The payment the hospital receives for providing an HRG spell is determined by whether that spell is elective and reflects the difference in costs associated with elective and non-elective patients.3 A single tariff exists to reimburse trusts for each HRG for day case and inpatient elective care.1 The key document introducing the payment by results policy was Reforming NHS Financial Flows.1 It identified three main reasons for introducing a standard price tariff: to “enable PCT [primary care trust] commissioners to focus on the quality and volume of services provided;” to “incentivise NHS Trusts to manage costs efficiently;” and to “create greater transparency and planning certainty in the system.” These objectives suggest linkages between the adoption of payment by results, change in the behaviour of decision makers, and subsequent changes in the performance of the NHS hospital system in England.

Before payment by results, several different purchasing arrangements were used in the English NHS. These were variously called block contracts, sophisticated block contracts, cost and volume contracts, and cost per case contracts.4 The first two of these arrangements accounted for most of hospitals’ income. Relative to the financing arrangements in place before its adoption, payment by results removes the option for hospitals to use their own cost circumstances to negotiate for higher payment. This feature of fixed price payment systems for health care gives rise to increased incentives to control costs.5 Any surplus earned by a hospital because it reduces its unit costs can be retained by the hospital to spend on other areas of its activity at its discretion.

However, fixed price payment systems may compromise quality of care.5 Providers can act to reduce costs in various ways: by increasing the efficiency with which they use resources to provide care, by selecting patients who need less resource intensive care, or by reducing the level of resources in the provision of care, which has a lowering effect on the quality of the patients’ care. Although the intention of the payment by results policy is that NHS trusts will respond to the fixed price with increases in efficiency, providing an incentive to reduce unit costs may compromise the quality of care provided.

Payment by results makes an explicit link between the number of patients treated and the payment to a hospital, whereas the predominant arrangements that it replaces left this link poorly defined. The logic of this seems clear: making an explicit payment for additional treatments provides incentives to provide more of those treatments. However, this will be the case only if the payment for a treatment is higher than the costs of providing the treatment, such that a surplus can be made and used for other purposes. In a complex healthcare setting, this surplus (or deficit) per treatment will vary across HRGs and also between trusts with different cost structures, so the incentive to increase output will vary across HRGs and between trusts.

Our objective was to examine whether changes in key outcome variables measuring the volume, cost, and quality of care during 2004/5 and 2005/6 were associated with tariff funding introduced for NHS hospitals in England under the payment by results policy.

Methods

Study design

When examining the impact of an intervention or change in policy, the challenge is to determine whether the observed changes over time are attributable to the intervention. A valid method of achieving this is by comparing the outcomes of the group subject to the intervention (the treatment group) with a group not subject to the intervention (the control group). For measuring the effect of healthcare interventions, this evaluation problem is most commonly solved by the use of an experiment in the form of a trial. However, such experiments, randomised or not, are rare in the field of health policy, and opportunities in the form of quasi-experiments or natural experiments have to be exploited.

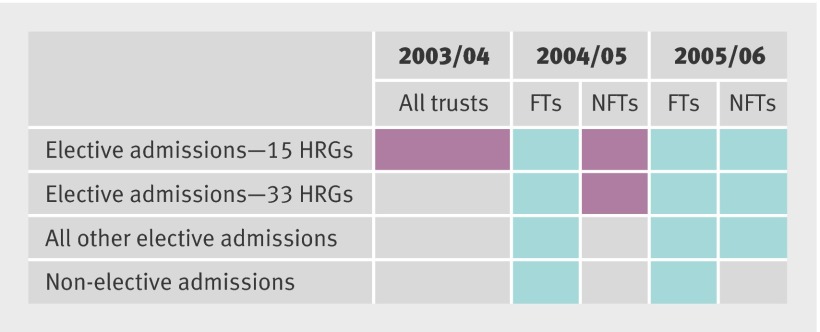

We therefore constructed a quasi-experiment using various naturally occurring control groups. The figure shows the introduction of the tariff system under payment by results in 2003/4 to 2005/6. The pink (darker) boxes indicate where the tariff is being applied in part: it was first applied to marginal changes in output for 15 HRGs in 2003/4 and extended to a further 33 HRGs in 2004/5.1 3 The blue (medium) boxes indicate where the tariff is being applied to all the spells of care. For a subset of NHS trusts—foundation trusts (box) and three early implementing non-foundation trusts—payment by results was applied to most inpatient, day case, and outpatient output activity in 2004/5. For the remaining non-foundation trusts, it was applied to most elective admissions in 2005/6.6 7 The grey (lighter) boxes indicate where the tariff is not being used. Throughout the period 2003/4 to 2005/6 the tariff system was not adopted in Scotland, and for most trusts in England it was not adopted extensively until 2005/6. This phased and partial introduction of payment by results provides a series of treatment and control groups.

Stages of implementation of payment by results, 2003/4 to 2005/6. FT=foundation trust; HRG=healthcare resource group; NFT=non-foundation trust

Foundation trusts

Foundation trusts are a type of NHS trust. They were created to give high performing trusts greater autonomy from control by central government. The first foundation trusts were established in April 2004; 29 existed by the end of 2004/5 and 34 by the end of 2005/6.

Ideally, the control group will be the same as the intervention group in everything other than the change in policy. In practice, differences usually exist between the two groups in observed and unobserved characteristics. However, a less onerous assumption is that, in the absence of the policy intervention, the unobserved differences between the two groups would be the same over time. Difference-in-differences analysis is a commonly used empirical technique in the evaluation of impacts of policy, which uses this assumption and is similar to a controlled before and after study but in a multivariate context.8 9 We used this technique to estimate average changes in key variables in the treatment and control groups before and after the introduction of payment by results and hence to estimate the average effects of payment by results. The absolute differences between the policy group and the control group are not important. It is the difference in differences, or the differences in the changes over time, that are subject to analysis. This means that our statistical methods strip out any potentially unobserved confounding differences in the control and treatment groups that are fixed over time, apart from any that are simultaneous with the implementation of payment by results in England. The analysis also controls for differences at baseline.

Non-foundation trusts and foundation trusts were subject to virtually all the same changes in policy over the period of study. Two differences are important to our study. The first is the difference in the timing of the introduction of payment by results, which we exploit in our study design. The second is that trusts gain greater financial freedoms on achieving foundation trust status. This may mean that they are better placed to respond to the financial incentives of payment by results or have a greater motivation to respond than the non-foundation trusts. If this is the case, we may overestimate the effects of payment by results when measuring its effects on key outcomes for foundation trusts in 2004/5. However, in order to achieve foundation trust status, non-foundation trusts have incentives other than payment by results to improve their performance. If this occurred for the control group in 2004/5, we may have underestimated the average effect of payment by results on the foundation trusts. Research elsewhere suggests that the financial performance of foundation trusts during the period of early achievement of this status was similar to that of non-foundation trusts.10

Although differences exist in aspects of the healthcare systems and policies of England and Scotland, they are broadly comparable. Seen in an international setting, given the possibilities in design of healthcare systems, the English and Scottish systems have considerable similarities. They essentially shared the same financing mechanisms and broad policy developments until the Scotland Act 1998. Both systems are predominantly funded through general taxation and provide services free at the point of consumption, and they both use family doctors as gatekeepers to secondary care services. They also have the same nationally agreed (UK) contracts for consultants, nurses, and general practitioners. The NHS in Scotland provides a structure similar to the English NHS, and importantly one that has been relatively stable in its financing of hospitals at the time of the implementation of payment by results. As a result, we consider that the NHS in Scotland provides a useful control in our analysis.

We used differences between the phasing in of payment by results by foundation trusts, non-foundation trusts, and Scotland to estimate the effects of the introduction of the policy. For each of the outcome measures used in the study, we made three main comparisons: between foundation trusts (treatment group) and non-foundation trusts (control) for changes from 2003/4 to 2004/5, using the difference that payment by results was implemented for foundation trusts in 2004/5; between foundation trusts (treatment group) and providers in Scotland (control) for changes from 2003/4 to 2004/5, using the same difference; and between non-foundation trusts (treatment group) and providers in Scotland (control) for changes from 2004/5 to 2005/6, using the difference that payment by results was first implemented for non-foundation trusts in 2005/6. We made a fourth comparison to analyse changes in foundation trusts over the full first two years of implementation of payment by results: between foundation trusts (treatment group) and providers in Scotland (control) for changes from 2003/4 to 2005/6.

Data sources

We used data from the hospital episode statistics for 2002/3 to 2005/6 for England and from the Scottish morbidity records (SMR01 and SMR02 ) for Scotland. Table 1 shows summary statistics. To match the unit of output to the unit of reimbursement, we converted the data from finished consultant episode level to spell level data (NHS Information Authority, Episodes to Spells Converter, version 3.1). A finished consultant episode represents the completion of a patient’s period of care under a consultant, after which the patient is either discharged or transferred to another consultant. A spell is the period of care in hospital from admission to discharge. It can consist of a single or multiple finished consultant episode(s). We used spells of activity in all subsequent analysis. To construct a model in which the “before” period did not include tariffed spells, we excluded spells within the list of 48 HRGs specified by the Department of Health for special application of the tariff in 2003/4 and 2004/5.1 3 The sample sizes shown in the results tables refer to the number of spells. They are large and vary with each model. The English data represent 248 acute care trusts, and the Scottish data come from 49 hospitals. Thirty four of the English trusts gained foundation status or were early implementers of payment by results during the period of analysis.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of hospital episode statistics and Scottish morbidity data

| 2001/2 | 2002/3 | 2003/4 | 2004/5 | 2005/6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of spells | |||||

| Non-foundation trusts | 7 629 806 | 7 526 797 | 7 820 040 | 7 958 654 | 8 347 898 |

| Foundation trusts | 1 617 327 | 1 845 650 | 1 929 056 | 1 973 753 | 2 077 994 |

| Scotland | 1 061 903 | 1 030 201 | 1 031 844 | 1 039 950 | 1 063 328 |

| Length of stay (days) | |||||

| Non-foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 4 802 745 | 4 704 459 | 4 946 759 | 5 060 002 | 5 243 302 |

| Mean | 10.33 | 8.80 | 8.16 | 7.89 | 7.42 |

| Foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 978 306 | 1 094 740 | 1 144 208 | 1 169 162 | 1 219 550 |

| Mean | 8.20 | 6.74 | 6.59 | 6.28 | 5.98 |

| Scotland: | |||||

| Number | 694 376 | 685 289 | 682 111 | 680 309 | 687 721 |

| Mean | 7.51 | 7.47 | 7.51 | 7.42 | 7.27 |

| In-hospital mortality | |||||

| Non-foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 7 629 806 | 7 526 797 | 7 820 040 | 7 958 654 | 8 347 898 |

| Mean | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 1 617 327 | 1 845 650 | 1 929 056 | 1 973 753 | 2 077 994 |

| Mean | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Scotland: | |||||

| Number | 1 061 903 | 1 030 201 | 1 031 844 | 1 039 950 | 1 063 328 |

| Mean | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 30 day post-surgical mortality | |||||

| Non-foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 3 240 116 | 3 256 791 | 3 337 277 | 3 352 583 | 2 960 147 |

| Mean | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 734 585 | 865 652 | 896 085 | 901 642 | 832 153 |

| Mean | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Scotland: | |||||

| Number | 499 288 | 481 190 | 481 268 | 486 319 | 508 204 |

| Mean | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture | |||||

| Non-foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 44 419 | 44 118 | 43 879 | 45 231 | |

| Mean | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | |

| Foundation trusts: | |||||

| Number | 9 205 | 9 340 | 9 211 | 9 344 | |

| Mean | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| Scotland: | |||||

| Number | 6 207 | 6 179 | 6 150 | 6 299 | |

| Mean | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | |

The rate of coding errors differed between the Scottish and English datasets. Unclassified spells or U codes in HRG 3.5 are generated mostly because of missing information on the required fields such as age, sex, date of admission, date of discharge, and length of stay. The hospital episode statistics data contained 2.68% of U codes in 2002/3, 2.93% in 2003/4, 2.40% in 2004/5, and 1.16% in 2005/6; the Scottish morbidity records data contained 1.34%, 1.37%, 1.36%, and 1.36% of U codes for the same years.

We used log length of stay (to give a close to normal distribution of the data) and day cases as a proportion of elective admissions as our two main measures of unit costs or efficiency for hospital admissions. For quality of care, we followed convention and used in-hospital mortality, 30 day post-surgical mortality, and emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture.

Econometric methods

We used fixed effects to control for differences between the characteristics of HRGs and trusts that were unobserved and did not change over time. Examples of such trust level characteristics are management culture, teaching status, and characteristics of the local population. HRG level unobserved factors include technology, specialty specific factors, patients’ demographics, and case mix within the HRG.

Other unobserved factors are likely to vary both within trusts and within HRGs. In addition, some trusts may be more efficient at providing particular HRGs and achieve better outcomes, and some HRGs will be highly specialised and will tend to be provided by particular types of trust both before and after the policy change. We therefore interacted the two variables to create fixed effects for each combination of HRG and trust. A total of 81 820 fixed effects exist. Inclusion of these effects ensured that we modelled changes in efficiency and quality associated with payment by results. Thus, we avoid the selection bias associated with attribution to payment by results of differences between trusts that determined whether they received foundation status. We also controlled for the characteristics of HRGs that determined whether they were deemed suitable for inclusion in payment by results.

For the analysis of length of stay, the data contain many zeros and the distribution of length of stay is skewed to the right. Because of this, we used a two part model and a log transformation of the dependent variable.11

Results

Impact on unit costs

The results for proxies of unit costs were consistent across most of the difference-in-differences analyses: they suggest that unit costs fell more quickly where payment by results was implemented (table 2). In all but one of the difference-in-differences comparisons used, foundation trusts and non-foundation trusts responded in the expected way to the incentives associated with payment by results. The first column in table 2 identifies the group of trusts to which the tariff is being applied; the second column is the control group used to estimate the difference in differences. The third column shows the year of analysis—for example, 2004/5 indicates the change in length of stay in 2004/5. The fourth and sixth columns contain the coefficients from the regression analysis. These show the change between the treatment group and the control group.

Table 2.

Effects of payment by results on measures of unit costs: length of stay (days) and proportion of day cases (change in percentage points)

| Treatment group | Control group | Years | Length of stay | Day case proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | No* | Change | No* | ||||

| Foundation trusts | Non-foundation trusts | 2003/4-2004/5 | 0.02† | 1091 | 0.4† | 8266 | |

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2004/5 | −0.08† | 2724 | 0.4† | 2810 | |

| Non-foundation trusts‡ | Scotland‡ | 2004/5-2005/6 | −0.03† | 1704 | 0.8† | 6842 | |

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2005/6 | −0.18† | 1248 | 1.5† | 1178 | |

*Number of observations in 1000s.

†Significant at P<0.01.

‡Elective only.

Length of stay generally fell more quickly where payment by results was implemented. In 2004/5 the average length of stay in foundation trusts fell by 0.08 of a day more than it did in Scotland. Expressed in whole days, this equates to eight inpatient days saved for every 100 inpatient admissions. For non-foundation trusts that implemented payment by results in 2005/6 the difference was in the same direction, indicating a faster reduction in average length of stay in non-foundation trusts than in Scotland by 0.03 days or a saving of three days per 100 admissions.

The proportion of elective care provided as day cases increased more quickly where payment by results was implemented. This change was seen for both foundation trusts and non-foundation trusts. In 2004/5 day cases as a proportion of elective care grew by 0.4 percentage points more in foundation trusts than in other providers, and in 2005/6 the proportion of elective care provided as day cases grew by 0.8 percentage points more in non-foundation trusts than in Scotland.

One difference-in-differences analysis using non-foundation trusts as the control for foundation trusts in 2004/5 did not support expectations. The non-foundation trusts, which were not subject to tariff, reduced length of stay more quickly than did the foundation trusts.

Impact on volume of spells

Using Scotland as the control group, we found that both foundation trusts and non-foundation trusts experienced a growth in volume associated with payment by results. The number of foundation trusts’ spells grew by 1.33 percentage points more than for providers in Scotland in 2004/5, and non-foundation trusts’ spells grew by 2.57 percentage points over and above growth in Scotland. However, the comparison of the tariffed response of foundation trusts with the non-tariffed response of non-foundation trusts, in 2004/5, shows that foundation trusts’ spells did not increase relative to the non-foundation trusts. This last result suggests that changes in policies other than payment by results that we were not able to control for in our analysis, such as waiting time targets, affected the growth in the volume of care in England relative to that in Scotland. Table 3 summarises the difference-in-differences results for the growth in volume of elective and non-elective spells.

Table 3.

Effects of payment by results on growth in volume of care (change in percentage points)

| Treatment group | Control group | Years | Growth in volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | No* | |||

| Foundation trusts | Non-foundation trusts | 2003/4-2004/5 | −0.25 | 82 816 |

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2004/5 | 1.33† | 20 431 |

| Non-foundation trusts‡ | Scotland‡ | 2004/5-2005/6 | 2.57† | 51 249 |

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2105/6 | 4.95† | 21 598 |

*Number of observations in 1000s.

†Significant at P<0.01.

‡Elective only.

Impact on quality of care

We found little evidence of an association between the introduction of payment by results and a change in the quality of care. Table 4 shows the difference-in-differences results for the three variables we used to measure quality: in-hospital mortality, 30 day post-surgical mortality, and emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture. The only result with statistical significance was the difference in the change in in-hospital mortality for foundation trusts compared with Scotland. A difference emerged when we looked at the longer term effects—that is, two years of impact of payment by results. This provided one piece of evidence that the quality of care in foundation trusts increased (represented by a reduction in in-hospital mortality) in association with the introduction of the tariff. No results support the proposition that quality of care has suffered as a result of payment by results. Most results indicate no associated change in quality.

Table 4.

Effects of payment by results on measures of quality of care: rates of in-hospital mortality, 30 day post-surgical mortality, and emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture (change in percentage points)

| Treatment group | Control group | Year | In-hospital mortality | 30 day mortality | Hip fracture emergency readmissions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | No* | Change | No* | Change | No* | |||||

| Foundation trusts | Non-foundation trusts | 2003/4-2004/5 | 0.01 | 19 744 | 0.01 | 6 775 | −0.68 | 107 | ||

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2004/5 | −0.05 | 5 090 | 0.03 | 2 215 | 0.73 | 29 | ||

| Non-foundation trusts‡ | Scotland‡ | 2004/5-2005/6 | −0.00 | 6 840 | −0.05 | 3 823 | 0.00 | 102 | ||

| Foundation trusts | Scotland | 2003/4-2005/6 | −0.28† | 2 192 | −0.00 | 1 046 | −1.20 | 14 | ||

*Number of observations in 1000s.

†Significant at P<0.01.

‡Elective only.

Discussion

Using a series of comparisons for each set of variables and using different controls within a difference-in-differences framework, we have examined whether, in response to the introduction of a fixed price tariff under payment by results, trusts have reduced unit costs, increased the volume of care, and changed the quality of care. Most of our tests on mean length of stay and the proportion of day case activity in total elective admissions are consistent with a reduction in unit costs associated with introduction of the tariff. Of the five tests on the effect of the tariff on the volume of care, four provided evidence that the tariff was associated with growth in activity. During their first full year of payment by results, foundation trusts did not experience the greater reductions in average length of stay and higher growth expected relative to non-foundation trusts. Only when they were compared with Scotland was a difference apparent. Both foundation trusts and non-foundation trusts seem to have increased volume and reduced length of stay relative to Scotland. This may reflect several pressures. Evidence from interviews with NHS managers suggests that other pressures in the form of waiting times targets and cash limits were driving these changes.12 The difference between trusts’ costs and the tariff may have influenced the response. Foundation trusts by definition are the more efficient and well managed trusts in England, with shorter lengths of stay. The tariffs are based on historical average costs, and foundation trusts may have experienced less pressure from the tariff to reduce costs than was the case in other trusts. In addition, the low absolute length of stay may have made it more difficult for foundation trusts to produce efficiency savings in this area. However, these very same foundation trusts should therefore have been in a better position to have benefited from increases in the volume of patients treated, but we did not see this in the data. The results for the effects on quality of care were generally not statistically significant and may be taken as evidence that payment by results did not have an adverse impact on the quality of care.

The results showing reductions in length of stay and increases in the proportion of day case activity provide support for the anticipated effects of the payment by results policy on hospitals’ costs. The damaging effects on the quality of care often anticipated in financing systems with fixed prices did not emerge in the results. Combining these two pieces of evidence points to the tentative conclusion that reductions in cost have been attained through increases in efficiency rather through reductions in quality.

Limitations

We used standard proxies for quality of care in our analysis: in-hospital mortality, 30 day post-surgical mortality, and emergency readmissions. Mortality has been criticised as an insufficiently sensitive measure of change in the quality of care.13 However, it is widely used in the absence of other routine data, such as quality of life outcomes measures, which may be more sensitive to changes in the quality of care.5 In-hospital mortality specifically is open to criticism as a means of measuring quality of care in a system that is also reducing length of stay. Reductions in in-hospital mortality may reflect patients dying outside hospital after rapid discharge. However, our (setting independent) 30 day mortality figures do not support the existence of this phenomenon.

We are confident that no change in the quality of care as measured by the proxies we have used has occurred. However, dimensions of quality of care that we have not captured could have been adversely affected by payment by results.

As described in the data sources section above, the proportion of unclassified spells has fallen more quickly in the hospital episode statistics data than in the Scottish data. U codes do not receive funding under payment by results, so the trend probably reflects the incentive to ensure that all activity is assigned an HRG code. We dropped all U coded spells from the analysis. This may have slightly inflated the effect of the tariff on the growth of spells.

Difference-in-differences analysis is a methodological framework widely used to evaluate the effects of policy.8 9 We have exploited the natural experiment that was created by the stepped introduction of the payment by results policy in England and the absence of payment by results in Scotland. The method controls for differences between the two countries that do not vary over time. Ideal conditions for applying difference-in-differences analysis require that in the absence of the policy intervention the average outcomes for the treatment and control groups would be parallel over time. Although policy differences exist between the two countries, provided these differences are time invariant, the method “nets” these out. However, if a policy, other than payment by results, that might influence the outcomes in which we were interested changed in one country and not the other, this may bias our results. “Patient choice” is one such policy, which is expected to complement the effects of payment by results. However, it was not implemented until the final quarter of the final year of data used in our analysis. Therefore, we do not anticipate that it will have significantly affected our results. Of more concern is the differential in waiting times introduced in 2004/5. Waiting time targets of the same level were used in England and Scotland throughout the period of our study with the exception of the six months target in England for the end of 2004/5 compared with nine months in Scotland. However, the rewards and sanctions associated with meeting or not meeting waiting time targets have been stronger in England during this period, and Propper et al found greater reductions in waiting times corresponding to these incentives.14 This additional incentive in England to increase the throughput of patients may have had a confounding effect on the results for the growth in the volume of spells in 2004/5 and may explain the lack of difference in growth of the tariffed foundation trusts and the non-tariffed non-foundation trusts in that year.

The results of this study refer specifically to the effects of the payment by results policy in its early years of implementation and may not necessarily be extrapolated forwards as the tariff continues to be used in England. The providers’ response may become more pronounced as the policy matures. Firstly, as hospitals become more familiar with the likely effects on their own costs and revenues of responding to the incentives of payment by results, they may be less cautious in their responses. Secondly, as hospital managers and clinicians become more confident about the permanence of payment by results and its prices, they may be more likely to respond to its incentives. Thirdly, our study covers a period when most hospitals affected by payment by results were on a transition pathway that partially protected them from financial losses associated with the tariff. As this protection reduces, the incentives of payment by results may be strengthened and the responses changed accordingly. Clearly, further research is needed to monitor the changing effects of payment by results on key outcomes in the English healthcare system.

Key findings in context

An activity based finance system using diagnostic related groups was first developed in the United States and used to pay hospitals as part of the publicly funded Medicare programme in 1983.15 Since then more than 20 healthcare systems in Europe, Australia, Asia, and Africa have adopted similar financing mechanisms based on diagnostic related groups.16 The dominant motivation for adopting activity based financing has been to control total healthcare costs and introduce incentives to increase efficiency, although some systems were also targeting waiting times and in turn the volume of care.17 Reductions in unit costs, with reduced length of stay as a proxy, are a commonly seen effect of the systems, and, on occasion, quite dramatic reductions have been seen.5

Less agreement exists on the effects of financing based on diagnostic related groups on the quality of care. A common theme in the literature is the inadequacy of using variables from administrative data as measures of quality. Despite this, and in the absence of other measures, the main outcomes used to measure changes in the quality of care are mortality (before and after discharge) and readmission rates extracted from such routinely collected data. Less commonly, surveys of patients have been used.18 Evidence from the United States suggesting a negative impact on quality of care after the introduction of activity based financing has not been reproduced for European countries adopting similar systems.19 However, whether these findings reflect the effects of the policy, the different underlying healthcare systems in the United States and European countries, or the inadequacy of the proxies for quality remains a debated issue.

Nordic countries adopting activity based financing (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland) have generally done so with the explicit aim of increasing productivity and reducing patients’ waiting times for hospital care.20 Empirical analysis of the effects of some of these schemes on output cautiously provides evidence of a positive relation between diagnostic related groups pricing and output in Norway,17 although the effects seem to have been temporary in Sweden.21

Some papers have commented on the likely effects of the introduction of payment by results in England,22 23 24 and a body of empirical analysis is emerging. The empirical based papers have examined the impact on management of demand and administrative costs,25 transaction costs,26 “HRG drift,”27 waiting times, the process of implementation,28 and similar key outcomes to the ones presented in this paper.29 A report by the Audit Commission draws on a similar time period to the research reported here, and the findings mirror those of our evaluation.29 Our research provides the first robust empirical analysis that uses econometric techniques to control for other confounding factors that may be influencing key outcomes.

Implications

Our substantive quantitative analysis of the effects of payment by results on key outcomes provides evidence of reductions in unit costs of hospital care associated with the introduction of payment by results in England in its early years of implementation. Less unequivocal evidence shows that payment by results has stimulated increases in the volume of spells. With respect to quality of care, the evidence should be treated with caution because, in common with other researchers, we were limited by the availability of proxies for the complexity that is “quality” of health care. Our results suggest that the reductions in unit costs have been achieved without a detrimental impact on the quality of care, at least in as far as these are measured by our proxy variables.

Taken together, the analyses suggests that payment by results is capable of achieving, and has in the short time since its adoption actually achieved, real changes in delivery of health care in hospitals in England. Looking forward, our evaluation suggests a potentially rich set of further research questions. Our approach has of necessity been a general one; much remains to be learnt about the impact of payment by results at a more disaggregate level.

What is already known on this topic

In April 2002 the Department of Health in England outlined plans to introduce a new system of financing hospitals, called payment by results

The system directly links the income hospitals receive with the number and case mix of patients treated

Similar systems adopted in other countries have been shown to have effects on the cost, quality, and volume of patients’ care

What this study adds

The results show a reduction in unit costs (with average length of stay and proportion of day cases as proxies) associated with the introduction of payment by results

The evidence on volume of care is more equivocal but suggests that the volume of spells of care increased in response to the new payment system

Payment by results had no effect on the outcomes used as proxies for the quality of care

Contributors: SF conceived and led the study and drafted and finished the paper. DY prepared the database, did the econometric analysis, and contributed to writing the paper. MS contributed to the design, oversaw the econometric analysis, and contributed to writing the paper. MC contributed to the design of the study and the writing of the paper. JS advised on the analysis and contributed to writing of the paper. AS advised on the design of the study and contributed to the analysis and the writing of the paper. SF is the guarantor.

Funding: This research was funded by the Department of Health through the Policy Research Programme. The researchers are independent of the funders. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not the funding body.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3047

References

- 1.Department of Health. Reforming NHS financial flows: introducing payment by results. London: Department of Health, 2002.

- 2.Sussex J, Street A. Activity-based financing for hospitals: English policy and international experience. London: Office of Health Economics, 2005.

- 3.Department of Health. NHS reference costs 2003 and national tariff 2004 (payment by results core tools 2004). London: Department of Health, 2004.

- 4.Raftery J, Robinson R, Mulligan J, Forrest S. Contracting in the NHS quasi-market. Health Econ 1996;5:353-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalkley M, Malcolmson JM. Government purchasing of health services. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, eds. Handbook of health economics. Vol 1A. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 2000:847-90.

- 6.Department of Health. Implementing payment by results: technical guidance 2005/06 (version 2.0). London: Department of Health, 2005.

- 7.Department of Health. Implementing payment by results. technical guidance 2005/06 (version 1.0). London: Department of Health, 2004.

- 8.Blundell R, Costa Dias M. Evaluation methods for non-experimental data. Fiscal Studies 2000;21:427-68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin J, Zhang B. Empirical likelihood based on difference-in-differences estimators. J R Stat Soc 2008;70:329-49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marini G, Miraldo M, Jacobs R, Goddard M. Giving greater financial independence to hospitals—does it make a difference? The case of English NHS trusts. Health Econ 2008;17:751-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ 2005;24:465-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussex J, Farrar S. Activity-based funding for National Health Service hospitals in England: managers’ experience and expectations. Eur J Health Econ 2009;10:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitches DW, Mohammed MA, Lilford RJ. What is the empirical evidence that hospitals with higher-risk adjusted mortality rates provide poorer quality of care? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Propper C, Sutton M, Whitnall C, Windmeijer F. Did ‘targets and terror’ reduce waiting times in England for hospital care? Bristol: University of Bristol, 2007. (Centre for Market and Public Organisation working paper series number 07/179.)

- 15.Newhouse JP, Byrne DJ. Did Medicare prospective payment system cause length of stay to fall? J Health Econ 1988;7:413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roger-France F. Case mix use in 25 countries: a migration success but international comparisons failure. Int J Med Inform 2003;70:215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kjerstad E. Prospective funding of general hospitals in Norway—incentives for higher production? Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2003;3:231-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljunggren B, Sjoden P-O. Patient reported quality of care before and after the implementation of a diagnosis related groups classification and payment system in one Swedish county. Scand J Caring Sci 2001;15:283-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dismuke CE, Guimaraes P. Has the caveat of case-mix based payment influenced the quality of inpatient hospital care in Portugal? Appl Econ 2002;34:1301-7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siciliani L, Hurst J. Tackling excessive waiting times for elective surgery: a comparative analysis of policies in 12 OECD countries. Health Policy 2005;72:201-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikkola H, Keskimaki I, Hakkinen U. DRG-related prices applied in a public health care system—can Finland learn from Norway and Sweden? Health Policy 2001;59:37-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon J. Payment by results: new financial flows in the NHS. BMJ 2004;328:969-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Street A, Sawson H. Would Roman soldiers fight for the financial flows regime? The re-issue of Diocletian’s English NHS. Public Money and Management 2004;24:301-8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appleby J, Renu J. Payment by Results: the NHS financial revolution. New Economy 2004;11:195-200. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannion R, Street A. Payment by results and demand management: learning from the South Yorkshire Laboratory. University of York, 2006. (Centre for Health Economics working paper 14, available at www.york.ac.uk/inst/che/pdf/rp14.pdf.)

- 26.Marini G, Street A. A transaction costs analysis of changing contractual relations in the English NHS. Health Policy 2007;83:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers R, Williams S, Jarman B, Aylin P. “HRG drift” and payment by results. BMJ 2005;330:563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Audit Commission. Early lesson of payment by results. London: Audit Commission, 2005.

- 29.Audit Commission. The right result? Payment by results 2003-07. London: Audit Commission, 2008.