Abstract

Objective To evaluate ascertainment of the onset of community transmission of influenza A/H1N1 2009 (swine flu) in England during the earliest phase of the epidemic through comparing data from two surveillance systems.

Design Cross sectional opportunistic survey.

Study samples Results from self samples by consenting patients who had called the NHS Direct telephone health line with cold or flu symptoms, or both, and results from Health Protection Agency (HPA) regional microbiology laboratories on patients tested according to the clinical algorithm for the management of suspected cases of swine flu.

Setting Six regions of England between 24 May and 30 June 2009.

Main outcome measure Proportion of specimens with laboratory evidence of influenza A/H1N1 2009.

Results Influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections were detected in 91 (7%) of the 1385 self sampled specimens tested. In addition, eight instances of influenza A/H3 infection and two cases of influenza B infection were detected. The weekly rate of change in the proportions of infected individuals according to self obtained samples closely matched the rate of increase in the proportions of infected people reported by HPA regional laboratories. Comparing the data from both systems showed that local community transmission was occurring in London and the West Midlands once HPA regional laboratories began detecting 100 or more influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections, or a proportion positive of over 20% of those tested, each week.

Conclusions Trends in the proportion of patients with influenza A/H1N1 2009 across regions detected through clinical management were mirrored by the proportion of NHS Direct callers with laboratory confirmed infection. The initial concern that information from HPA regional laboratory reports would be too limited because it was based on testing patients with either travel associated risk or who were contacts of other influenza cases was unfounded. Reports from HPA regional laboratories could be used to recognise the extent to which local community transmission was occurring.

Introduction

Prompt recognition of sustained community transmission in the earliest phase of an epidemic of a novel influenza virus is important to improve short term predictions, to guide public health decisions on switching from a policy of containment to one of mitigation,1 and for fulfilling criteria for WHO phases of pandemic alert.2 When laboratory confirmed cases of influenza A/H1N1 2009 (swine flu) in England steadily increased during May and June 2009, it was unclear whether community transmission had begun and whether the transmission rate in the country was increasing. A number of factors contributed to this uncertainty.

Foremost was the concern that if initial laboratory testing capacity concentrated on ill people with links to affected countries or who were in close contact with patients whose symptoms had been microbiologically confirmed,3 then surveillance would fail to recognise the extent to which local community transmission was occurring.4 In addition, existing syndromic surveillance systems might not have been sufficiently specific during the early stages of the epidemic. The influenza syndromic surveillance capability of the Health Protection Agency (HPA) includes the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Weekly Returns Service5 and the QSurveillance system (University of Nottingham and Egton Medical Information Systems Ltd),6 which analyse anonymised morbidity data automatically extracted from networks of participating general practices. Since the beginning of the influenza A/H1N1 2009 epidemic, general practice diagnoses of influenza-like illness and a range of other respiratory tract infections (rates per 100 000 population) have been monitored on a daily (QSurveillance) and weekly basis (QSurveillance, RCGP), providing information for regular situation reports.7 Throughout May and most of June 2009, however, general practice consultation rates for influenza-like illness remained well below the upper limit for “baseline activity” of 30 cases per 100 000 population. Only during the second half of June did a clear increase in consultation rates became apparent in either the RCGP system or the QSurveillance system.8

One response to the perceived poor specificity of syndromic surveillance for recognising illness caused by the novel virus was the re-introduction of virological testing. During each influenza “season,” a programme of integrated nose and throat swabbing is conducted within the RCGP system.9 In addition, the HPA operates a Regional Microbiological Network general practice spotter scheme.10 Both systems were re-instigated to enhance community based virological surveillance. In May 2009, however, there was unease that the geographical scope of these sentinel virological sampling systems may have been too limited so that sustained community transmission may have been underascertained once begun and if concentrated in a few places. Moreover, once members of the public with suspect flu symptoms were advised in early May 2009 not to attend general practitioner surgeries or accident and emergency departments unless they were seriously ill or advised to do so,11 the case mix of those receiving primary care from their general practitioners was likely to have changed.

NHS Direct is a multi-channel health advice and information service for the population of England.12 In the telephone channel, operators use a series of clinical assessment algorithms to evaluate the symptoms of each patient and the predominant symptom is recorded. The service is nurse led, and other health professionals—such as pharmacists—are used where appropriate. Callers are triaged, and their reported symptoms and the severity are evaluated to produce recommended call outcomes that include advice for self care, referral to an emergency department, referral to urgent general practitioner care, or referral to routine general practitioner care. All outcomes are dependent on the seriousness of the call and the “risk status” of the caller—that is, whether they are young or old, or have other illnesses. The service is accessible all day, every day and provides a reliable and continuous feed of data that are utilised by the HPA Real-time Syndromic Surveillance Team to form the basis of the NHS Direct and HPA syndromic surveillance system.12 Previous work has demonstrated that call data are sensitive to increases in community transmission of a range of pathogens, including influenza. Daily numbers of calls recording cold or flu symptoms, or both (aggregated across all ages), and fever (in patients aged 5-14 years) provide early warning of the beginning of community influenza transmission in winter.13

During the swine flu epidemic, the existing NHS Direct and HPA syndromic surveillance system was augmented on 28 May 2009 with a scheme of self sampling and virological testing of telephone callers that had been piloted during the winter of 2003-2004.14 The clinical assessment algorithm used by NHS Direct for callers concerned about swine flu distinguished a subset of patients with generally uncomplicated illness who had no travel associated risk, no contact with other suspected or confirmed influenza A/H1N1 2009 cases, and had a “self care” call outcome.

In addition, laboratory confirmation of influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection before the end of May 2009 depended on the results of tests that were only available at the national reference laboratory. From 1 June 2009, however, suitable testing facilities became available throughout the HPA’s network of regional laboratories. Thereafter, the volume of clinical testing increased rapidly, as did the numbers of laboratory confirmed diagnoses.

The aim of our study was to compare, throughout June 2009 when the swine flu epidemic was taking hold, the weekly information from virological testing of self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers with information from laboratory testing of swabs taken from patients assessed with the clinical algorithm for management of patients with influenza-like illness to see what conclusions might be drawn about the timing of the onset of sustained community transmission. More specifically, we sought to know whether at the beginning of an epidemic the results from the swabs of NHS Direct callers could improve ascertainment of the onset and extent of sustained community transmission of a new influenza virus.

Methods

Members of the public who sought health advice over the telephone from NHS Direct12; were symptomatic for cold or flu symptoms, or both, according to a cold/flu algorithm; were aged 16 years or over; and were advised to self treat their symptoms or seek pharmacy advice (that is, those in whom primary care management was considered unnecessary) were asked to participate. These symptomatic patients represented “sporadic” cases of influenza-like illness, whereas callers who had recently returned from an affected country or who had contact with a confirmed case were referred for primary care management, including clinical testing. Patients from the following six Strategic Health Authorities were sampled: the North East (population 2.6 million); the East Midlands (population 4.4 million); the East of England (population 5.7 million); the South East (population 8.3 million); London (population 7.6 million); and the West Midlands (population 5.4 million).

Patients were sent to their home address a self sampling kit that included an explanatory letter, a dry swab, instructions for taking a nasal swab, a viral transport medium, a short questionnaire, and pre-paid packaging to return specimens to a central laboratory.14 The packaging fulfilled packaging instruction PI 650 in conformity with the UN 3373 regulation. Returned nasal swabs were tested for influenza A/H1N1 2009 virus, seasonal influenza virus (influenza A/H1N1, influenza A/H3N2, and influenza B/H1N1), human respiratory syncytial virus, and human metapneumovirus. The letter made clear that the scheme was not a diagnostic service and that participation did not guarantee callers would be sampled. Infections ascertained through the scheme were reported to the patient’s general practitioner, who was asked to arrange further clinical management according to existing guidelines. In order to maintain consistent and manageable numbers of self obtained samples for laboratory testing, the daily number of eligible NHS Direct patients was limited by only sending self sampling kits to callers located within the regions where clinical diagnoses were increasing (West Midlands and London) and in another four regions that were much less affected.

During the same period, suspect cases of swine flu were being ascertained largely through patients or concerned persons responding to media interest and contacting their general practitioners or through the active follow-up by public health services of contacts of confirmed or suspect cases, often where local school outbreaks had been recognised. Once ascertained, suspect cases were assessed according to the current clinical management algorithm,3 and specimens were taken for laboratory investigation at the HPA regional laboratories. These laboratories provided daily electronic returns to the national surveillance centre. The data from these daily returns were summarised by region and the information used for national situation reports, as was the information from the NHS Direct self sampling scheme.7 8

The self sampling participant questionnaire collected data regarding presenting symptoms, date of symptom onset, and date of self swab. The date of self swab was used to calculate the week of specimen. Where the exact date of self swab was unavailable, a date was estimated using the date the specimen was received at the central laboratory. The data from HPA regional laboratories were categorised by week of swab. Where the exact date was unavailable, the date the swab was received at the HPA regional laboratory was used. Where appropriate, exact binomial confidence intervals and Fisher’s exact P values were calculated using Stata 10.1.15 16

For the purposes of this study, the number of cases diagnosed by the HPA regional laboratories during June was used to categorise the six regions where the NHS Direct self sampling took place (covering 66% of the population of England) as mildly (50 to 199 cases), moderately (200 to 999 cases), and severely (more than 1000 cases) affected.

Results

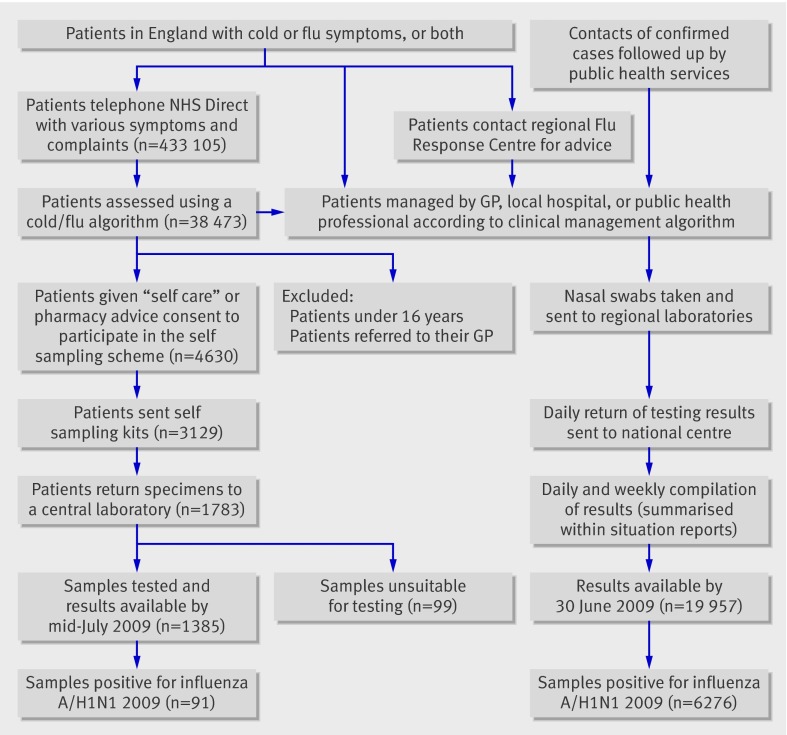

Of the 433 105 callers to NHS Direct between 28 May and 30 June 2009, 38 473 (9.1%) callers were assessed using a cold/flu clinical algorithm and 4630 agreed to self sample. Specimens were received from 1783 (57%) of the 3129 callers sent self sampling packs, and testing was completed on 1385 (82%) individuals by mid-July (figure). Influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection was detected in 91 samples (7% of those tested, 95% confidence interval 5% to 8%). In addition, eight influenza A/H3 infections and two influenza B infections were identified. During the same period, HPA laboratories in the six regions studied tested 19 957 individuals and confirmed influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection in 6276 people (31%, 95% CI 31% to 32%).

Ascertainment of cases of influenza A/H1N1 2009 in the NHS Direct self swabbing scheme and by Health Protection Agency regional laboratories in England during June 2009

Most specimens collected via the NHS Direct scheme (1005/1373; 73%) were from patients with influenza-like illness, as defined by the cold/flu management algorithm,3 and 80% (1076/1346) were taken within seven days of symptom onset. Laboratory confirmed influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection was highest in people aged 16 to 24 years: 22% (40/182) of patients tested within the NHS Direct scheme and 37% (1123/3013) of those who underwent testing in HPA regional laboratories. In addition, the NHS Direct scheme detected the virus in 8% (26/325) of 25-34 year olds, 4% (22/556) of 35-54 year olds, and 1.3% (3/234) of individuals over 54; these proportions were 22% (670/2984), 16% (698/4311), and 8% (109/1421), respectively, in regional laboratory testing. In contrast, influenza A/H1N1 2009 virus was detected in 45% of the patients aged under 16 who were tested in HPA regional laboratories (3579/7881; table 1).

Table 1.

Overall weekly test results of NHS Direct callers and individuals suspected of swine flu according to the clinical algorithm in six regions of England, 24 May to 30 June 2009

| Week ending Tuesday 2 June* | Week ending Tuesday 9 June | Week ending Tuesday 16 June | Week ending Tuesday 23 June | Week ending Tuesday 30 June | Five week summary | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | |

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers tested by a central laboratory† | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 0/55 | 0% | 0% to 6% | 2/252 | 1% | 0% to 3% | 12/346 | 3% | 1% to 6% | 30/410 | 7% | 5% to 10% | 47/322 | 15% | 11% to 19% | 91/1385 | 7% | 5% to 8% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu tested by Health Protection Agency regional laboratories‡ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Under 16s | 46/165 | 38% | 21% to 35% | 101/379 | 27% | 22% to 31% | 466/1072 | 43% | 40% to 46% | 1349/2977 | 45% | 44% to 47% | 1617/3288 | 49% | 47% to 51% | 3579/7881 | 45% | 44% to 47% |

| 16 and over | 75/482 | 16% | 12% to 19% | 86/772 | 11% | 9% to 14% | 263/1742 | 15% | 13% to 17% | 863/3966 | 22% | 20% to 23% | 1315/4769 | 28% | 26% to 29% | 2602/11731 | 22% | 21% to 23% |

| Total§ | 124/656 | 19% | 16% to 22% | 189/1167 | 16% | 14% to 18% | 736/2854 | 26% | 24% to 27% | 2248/7062 | 32% | 31% to 33% | 2979/8218 | 36% | 35% to 37% | 6276/19957 | 31% | 31% to 32% |

The following six regions of England were sampled: the North East; the East Midlands; the East of England; the South East; London; and the West Midlands.

Exact binomial confidence intervals have been calculated for all data.

*NHS Direct self sampling initiated on 28 May 2009.

†Results from self obtained samples are by week of self swab.

‡Health Protection Agency regional laboratory results are by week of swab.

§Total includes laboratory results without age of the patient and, therefore, these data are not included within the age breakdown data.

During the weeks ending 2 June and 9 June 2009, only 2/307 (1%, 95% CI 0% to 2%) influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections were detected in the NHS Direct scheme compared to 161/1254 (13%, 95% CI 11% to 15%) among patients aged 16 and over tested by HPA regional laboratories (table 1). Thereafter, the number of infections and the proportion with infection in both groups increased steadily so that in the week ending 30 June 2009, influenza A/H1N1 2009 virus had been detected in 47/322 (15%, 95% CI 11% to 19%) of the NHS Direct samples and in 1315/4769 (28%, 95% CI 26% to 29%) samples from patients aged 16 years and over tested in HPA regional laboratories.

The rate of change in the proportions of influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections in the NHS Direct scheme each week within each of the six included regions closely matched the rate of increase in the proportions infected reported by HPA regional laboratories (table 2). Combining the NHS Direct data for the week ending 23 June and the week ending 30 June, the proportion positive in the two severely affected regions of West Midlands and London was 14% (95% CI 11% to 17%), which was significantly greater than the 3% positive in the mildly affected regions of North East and East Midlands (95% CI 1% to 9%; P=0.009). Only once regional laboratories began detecting per week 100 or more influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections or a proportion positive of more than 20% did the NHS Direct scheme begin to consistently detect infections (that is, the lower confidence limit on the proportion positive was not 0; table 2).

Table 2.

Overall weekly test results of NHS Direct callers and individuals suspected of swine flu according to the clinical algorithm in six regions of England, 24 May to 30 June 2009

| Week ending Tuesday 2 June* | Week ending Tuesday 9 June | Week ending Tuesday 16 June | Week ending Tuesday 23 June | Week ending Tuesday 30 June | Five week summary | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | x/n | Proportion positive | 95% CI | |

| Mildly affected | ||||||||||||||||||

| North East | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/3 | 0% | 0% to 71% | 0/9 | 0% | 0% to 34% | 1/18 | 6% | 0% to 27% | 0/31 | 0% | 0% to 11% | 1/12 | 8% | 0% to 38% | 2/73 | 3% | 0% to 10% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 0/12 | 0% | 0% to 26% | 25/88 | 25% | 19% to 39% | 9/160 | 6% | 3% to 10% | 10/193 | 5% | 3% to 9% | 18/204 | 9% | 5% to 14% | 62/657 | 10% | 7% to 12% |

| East Midlands | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/4 | 0% | 0% to 60% | 0/23 | 0% | 0% to 15% | 0/39 | 0% | 0% to 9% | 1/29 | 3% | 0% to 18% | 1/26 | 4% | 0% to 20% | 2/121 | 2% | 0% to 6% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 5/34 | 15% | 5% to 31% | 4/68 | 6% | 2% to 14% | 5/102 | 5% | 1% to 11% | 47/273 | 17% | 13% to 22% | 124/528 | 23% | 20% to 27% | 185/1005 | 18% | 16% to 21% |

| Moderately affected | ||||||||||||||||||

| East of England | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/10 | 0% | 0% to 31% | 0/35 | 0% | 0% to 10% | 0/38 | 0% | 0% to 9% | 4/41 | 10% | 3% to 23% | 2/47 | 4% | 1% to 15% | 6/171 | 4% | 1% to 7% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 23/62 | 37% | 25% to 50% | 6/100 | 6% | 2% to 13% | 19/164 | 12% | 7% to 17% | 116/428 | 27% | 23% to 32% | 232/813 | 29% | 25% to 32% | 396/1567 | 25% | 23% to 27% |

| South East | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/15 | 0% | 0% to 22% | 0/59 | 0% | 0% to 6% | 0/73 | 0% | 0% to 5% | 3/66 | 5% | 1% to 13% | 8/64 | 13% | 6% to 23% | 11/277 | 4% | 2% to 7% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 44/218 | 20% | 15% to 26% | 21/355 | 6% | 4% to 9% | 55/451 | 12% | 9% to 16% | 248/1182 | 21% | 19% to 23% | 350/1495 | 23% | 21% to 26% | 718/3701 | 19% | 18% to 21% |

| Severely affected | ||||||||||||||||||

| London | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/17 | 0% | 0% to 20% | 0/69 | 0% | 0% to 5% | 3/65 | 5% | 1% to 13% | 10/99 | 10% | 5% to 18% | 21/91 | 23% | 15% to 33% | 34/341 | 10% | 7% to 14% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 25/164 | 15% | 10% to 22% | 36/256 | 14% | 10% to 19% | 201/702 | 29% | 25% to 32% | 930/2523 | 37% | 35% to 39% | 1144/2545 | 45% | 43% to 47% | 2336/6190 | 38% | 37% to 39% |

| West Midlands | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self obtained samples from NHS Direct callers† | 0/6 | 0% | 0% to 46% | 2/57 | 4% | 0% to 12% | 8/113 | 7% | 3% to 13% | 12/144 | 8% | 4% to 14% | 14/82 | 17% | 10% to 27% | 36/402 | 9% | 6% to 12% |

| Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu‡ | 27/166 | 16% | 11% to 23% | 97/300 | 32% | 27% to 38% | 447/1275 | 35% | 32% to 38% | 897/2463 | 36% | 35% to 39% | 1111/2633 | 42% | 40% to 44% | 2579/6837 | 38% | 37% to 39% |

Exact binomial confidence intervals have been calculated for all data.

*NHS Direct self sampling initiated on 28 May 2009.

†Results from self obtained samples are by week of self swab.

‡Clinical samples from suspect cases of swine flu were tested by Health Protection Agency regional laboratory and are shown by week of swab.

Discussion

Self sampling by 1385 callers to NHS Direct detected “sporadic” influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections in 91 (7%) individuals and showed local community transmission was occurring in London and the West Midlands regions.

Our six region systematic virological testing of self sampled NHS Direct callers over the initial period of influenza A/H1N1 2009 circulation in England shows that the trends in clinical diagnoses reported by HPA regional laboratories provided a reliable indication of the extent to which local transmission was occurring. In the regions where the numbers and proportions of clinical specimens positive for influenza A/H1N1 2009 were low, the self sampling scheme operating via NHS Direct likewise suggested an absence of sustained community transmission. In regions where the proportion of clinical specimens positive for influenza A/H1N1 2009 were rising rapidly, however, the self sampling scheme provided complementary and less biased evidence of increasing community transmission than that provided by reported laboratory diagnoses. Comparing the data from both systems showed that local community transmission was occurring once HPA regional laboratories began detecting 100 or more influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections, or a proportion positive of over 20% of those tested, each week. The initial concern that information from HPA regional laboratory reports would be too limited because it was based upon testing patients with either travel associated risk or who were contacts of other influenza cases was unfounded. Reports from HPA regional laboratories could be used to recognise the extent to which local community transmission was occurring.

Interestingly, the self sampling results also show community transmission of seasonal influenza A/H3 and B viruses in early summer, which is a rare observation given that influenza virological surveillance schemes are usually suspended from May (week 21) to September (week 39) each year.

Comparison with other studies

This work follows the NHS Direct self sampling pilot conducted during the influenza season of 2003-2004.14 The sample return rate of NHS Direct callers was higher during the current swine flu epidemic than in the pilot (57% versus 42%, respectively 14). Increased public interest and awareness of the swine flu epidemic, primarily driven by media reporting during the early stages of the outbreak, may have resulted in a greater proportion of NHS Direct callers who were interested in knowing the specific cause of their illness.

There are very few studies that have used self sampling of patients for microbiological or pathological screening. Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae has been reported using self collected vaginal swabs in women17 18 and self obtained pharyngeal and rectal swabs in men.19 These self sampling methods for sexually transmitted infection testing have provided results comparable to those collected by clinicians.17 19 In addition, a number of human papillomavirus studies have compared samples collected by patients with those obtained by clinicians, with reasonable concordance between the two sets of samples.20 21 Our results confirm that it is feasible to obtain samples for routine microbiological testing from patients with acute respiratory illness without the intervention of a clinician.

Strengths and limitations

Early clinical investigation algorithms used in regional reporting are understandably biased towards detecting cases among patients exposed to affected countries or to known cases. An advantage of using NHS Direct self sampling in parallel with clinical case reporting and HPA regional laboratory testing is that self sampling provided a relatively unbiased picture of “sporadic” community transmission and thus strengthened the ascertainment of the onset of community transmission of influenza A/H1N1 2009. Another advantage is that the NHS Direct self sampling scheme did not depend on patients presenting to primary care, which is important given that public health advice to reduce transmission discouraged patients suspected of having influenza from attending primary care services.

The NHS Direct self sampling survey was limited to individuals aged 16 years or over (in accordance with the pilot study14) and to those who were not advised to seek further medical attention. Self sampling kits were sent and returned using the postal service, whereas patients attending for clinical management would have been sampled immediately and their specimens were probably returned faster to HPA regional laboratories.

It could also be argued that the increases in the proportion of patients positive for influenza A/H1N1 2009 detected by HPA regional laboratories during June were affected by changes in the mix of patients being sampled; however, the self sampling data also show that cases were increasing during this time, especially in those areas where regional laboratory testing was finding a high number of cases.

Another possible limitation is that patients might have both provided a self obtained sample and given a sample for testing to their general practitioner, and thus could be included in both study populations. Given that the NHS Direct self sampling scheme was offered only to callers with a “self care” or “pharmacy advice” outcome and not to those referred to “GP care,” the potential for patients to be sampled in both the NHS Direct scheme and the general practice scheme was small. In addition, after early to mid May 2009 patients with suspected influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection included within the general practice virological surveillance schemes would generally have had an extra reason to attend their general practitioner, such as “serious illness,” owing to the recommendation that people with “uncomplicated” influenza symptoms should not visit their GP 11).

Conclusions and policy implications

Self sampling of NHS Direct callers provided a system complementary to laboratory testing to monitor influenza A/H1N1 2009 transmission in the subset of patients with uncomplicated illness who had no travel associated risk and no known contact with other influenza cases. In addition, the trends in clinical diagnoses reported by HPA regional laboratories over the initial period of influenza A/H1N1 2009 circulation in England provided a reliable indication of the extent to which local transmission was occurring.

The self sampling of members of the public with cold or flu symptoms, or both, who telephoned NHS Direct changed considerably in early July 2009 when a system change to managing callers was introduced in response to large increases in swine flu calls. When the National Pandemic Flu Service (NPFS) was launched on 23 July 2009,22 the majority of calls to NHS Direct that were related to influenza were redirected to the NPFS. If the current epidemic of influenza A/H1N1 2009 intensifies through the coming autumn and winter, self sampling of selected callers to clinical advice services should enable relatively unbiased monitoring of the proportion of mild influenza-like illness attributable to particular influenza types in different regions, as well as both the antiviral susceptibility of strains and any antigenic drift. Such a scheme began operating from 3 August 2009 with respect to callers to the NPFS.23

What is already known on this topic

Prompt recognition of sustained community transmission during an influenza pandemic can improve short term predictions, guide public health decisions, and affect the criteria for WHO phases of pandemic alert

If initial laboratory testing capacity is concentrated on ill people with links to affected countries or who are close contacts of cases that are already microbiologically confirmed, surveillance based on reports of such cases may fail to recognise the extent of local community transmission

Laboratory confirmed cases of influenza A/H1N1 2009 increased steadily during the first eight weeks of the swine flu epidemic in England, but there was uncertainty as to whether local community transmission had begun

What this study adds

Self sampling of NHS Direct callers provided a system complementary to laboratory testing to monitor influenza A/H1N1 2009 transmission in the subset of patients with generally uncomplicated illness who had no travel associated risk and no known contact with other influenza cases

Self sampling by 1385 callers to NHS Direct detected “sporadic” influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections in 91 (7%) people and showed the regions where local community transmission was occurring

Comparing the data from both systems showed that local community transmission was happening once Health Protection Agency regional laboratories began detecting 100 or more influenza A/H1N1 2009 infections, or a proportion positive of over 20% of those tested, each week

We are grateful to members of the Regional Microbiology Network for providing access to the regional diagnostic laboratory data used within this report.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. AJE, CP, AT, CO, CH, IS, DF, EP, GES, and ONG all contributed to the extraction and processing of NHS Direct call data and the selection of self sampling participants. JE, AB, PS, AL, MZ, and DB contributed to the laboratory testing of samples. PW and TW contributed the data on testing by Health Protection Agency regional laboratories. AJE and ONG collaborated to write the manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting and have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This enhanced surveillance was undertaken as part of the national surveillance function of the Health Protection Agency.

Competing interests: None declared.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3403

References

- 1.Department of Health. Pandemic flu: a national framework for responding to an influenza pandemic. November 2007. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_080734.

- 2.Department of Health. World Health Organization (WHO) has announced a move to pandemic phase 6. 11 June 2009. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Flu/Swineflu/DH_100693.

- 3.Sir Liam Donaldson, Chief Medical Officer. Swine Flu Alert 1 May 2009. https://www.cas.dh.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=101203.

- 4.MacKenzie D. Europe may be blind to swine flu cases. New Scientist 20 May 2009. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20227094.400-europe-may-be-blind-to-swine-flu-cases.html.

- 5.Fleming DM, Elliot AJ. Lessons from 40 years’ surveillance of influenza in England and Wales. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:866-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippisley-Cox J, Smith S, Smith G, Porter A, Heaps M, Holland R, et al. QFLU: new influenza monitoring in UK primary care to support pandemic influenza planning. Euro Surveill 2006;11:E060622.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre, NHS Direct, Nottingham University Division of Primary Care, HPA Real-time Syndromic Surveillance Team. Primary care section of Health Protection Report. 14 August 2009. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/infections/primarycare.htm.

- 8.Health Protection Agency. HPA weekly national influenza report 24 June 2009 (week 26). http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1245581558905.

- 9.Zambon MC, Stockton JD, Clewley JP, Fleming DM. Contribution of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus to community cases of influenza-like illness: an observational study. Lancet 2001;358:1410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph C. Virological Surveillance of influenza in England and Wales: results of a two year pilot study 1993/94 and 1994/95. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev 1995;5:R141-R145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. Swine flu information leaflet, 4 May 2009. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Flu/Swineflu/News/DH_102125.

- 12.Smith GE, Cooper DL, Loveridge P, Chinemana F, Gerard E, Verlander N. A national syndromic surveillance system for England and Wales using calls to a telephone helpline. Euro Surveill 2006;11:220-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper DL, Verlander NQ, Elliot AJ, Joseph CA, Smith GE. Can syndromic thresholds provide early warning of national influenza outbreaks? J Public Health 2009;31:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper DL, Smith GE, Chinemana F, Joseph C, Loveridge P, Sebastianpillai P, et al. Linking syndromic surveillance with virological self-sampling. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2nd edn. Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1987.

- 16.Intercooled Stata version 10.1 [program]. Stata Corporation, 2009.

- 17.Fang J, Husman C, DeSilva L, Chang R, Peralta L. Evaluation of self-collected vaginal swab, first void urine, and endocervical swab specimens for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008;21:355-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, Aumakhan B, Holden J, Hardick A, et al. Performance of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of self-collected vaginal swabs obtained via an Internet-based screening program. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:1663-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander S, Ison C, Parry J, Llewellyn C, Wayal S, Richardson D, et al. Self-taken pharyngeal and rectal swabs are appropriate for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in asymptomatic men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:488-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longatto-Filho A, Roteli-Martins C, Hammes L, Etlinger D, Pereira SM, Erzen M, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing as cervical cancer screening option. Experience from the LAMS study. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2008;29:327-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart DE, Gagliardi A, Johnston M, Howlett R, Barata P, Lewis N, et al. Self-collected samples for testing of oncogenic human papillomavirus: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007;29:817-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health. Dear colleague letter: A (H1N1) swine influenza: launch of the national pandemic flu service. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_103224.

- 23.Health Protection Agency. HPA weekly national influenza report 13 August 2009 (week 33). http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1250148897195.