Abstract

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with an ovarian teratoma is a very rare disease. However, treating teratoma is the only method to cure the hemolytic anemia, so it is necessary to include ovarian teratoma in the differential diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. We report herein on a case of a young adult patient who had severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia that was induced by an ovarian teratoma. A 25-yr-old woman complained of general weakness and dizziness for 1 week. The hemoglobin level was 4.2 g/dL, and the direct and indirect antiglobulin tests were all positive. The abdominal computed tomography scan revealed a huge left ovarian mass, and this indicated a teratoma. She was refractory to corticosteroid therapy; however, after surgical resection of the ovarian mass, the hemoglobin level and the reticulocyte count were gradually normalized. The mass was well encapsulated and contained hair and teeth. She was diagnosed as having autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with an ovarian teratoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such a case to be reported in Korea.

Keywords: Teratoma; Ovary; Anemia, Hemolytic, Autoimmune

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) can be induced by a variety of causes. The tumors that induced AIHA are usually hematologic neoplasms such as malignant lymphoma (1, 2). There have been a few reports of AIHA associated with ovarian tumors worldwide, and most of them were ovarian dermoid cysts (3-6). The mechanism of hemolysis has not yet been defined. However the only effective treatment for hemolysis is tumor removal (3-6), so it is important for physicians to know that teratoma is one of the etiologies of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Ovarian mature cystic teratoma is very rare cause of AIHA, and we could not find any reports on this in the KoreaMed. We report here a case of severe AIHA associated with an ovarian mature cystic teratoma, and the patient's hemolysis was successfully treated via tumor resection.

CASE REPORT

A 25-yr-old female was admitted to our hospital with complaints of weakness and dizziness of one week's duration. She also complained of fever, vague abdominal pain, and dark colored urine. She did not have any significant prior medical history and there was no recent drug exposure. The initial blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, the pulse rate was 100/min, and the body temperature was 38℃. There was neither palpable abdominal mass nor other specific findings on the physical examination except for her pale appearance.

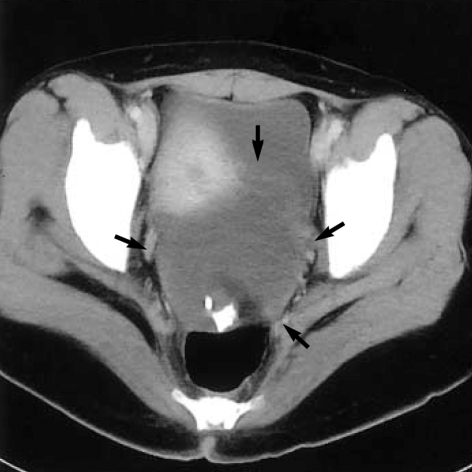

At the time of admission her hemoglobin level was 4.2 g/dL, and the reticulocyte count was 23.5% (corrected count: 5.74%). Marked polychromasia with spherocytosis and nucleated red blood cells were noted on the peripheral blood smear. The serum lactate dehydrogenase level was 1,842 IU/L (240-460 IU/L), total bilirubin, 2.73 mg/dL (0.4-1.3 mg/dL), haptoglobin, 38 mg/dL (70-380 mg/dL), and vitamin B12, 369 pg/mL (225-1,100 pg/mL). The blood group was A, Rh-positive. The direct and indirect antiglobulin tests were all positive. Serum autoantibody testing against red blood cells was positive, and anti-nuclear antibody and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody tests were negative. The abdominal computed tomography revealed a huge left ovarian cystic mass and hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomographic scan shows a huge ovoid mass (arrows) with multiple calcific nodules anterior to rectum.

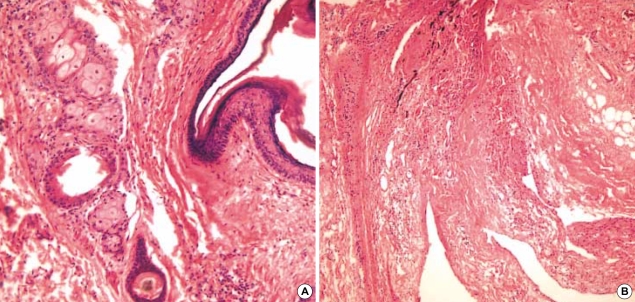

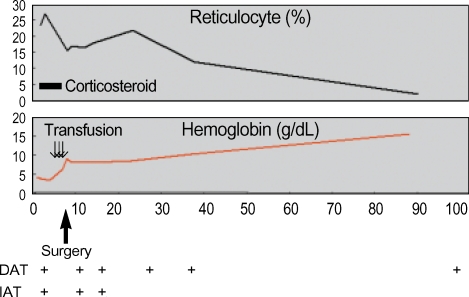

We started to treat her with prednisolone, 1.5 mg/kg/day. However the hemoglobin level gradually decreased to 3.3 g/dL, and she complained of resting chest discomfort 2 days after prednisolone. We performed transfusion with packed red blood cell in spite of the positive cross matching, and the persistent autoantibody. We stopped treating her with prednisolone after 7 days, and then resected the ovarian tumor. The tumor was 13×9×7 cm sized, well encapsulated mass and the mass was cystic and multiloculated. The cystic content was greasy, and composed of keratin, sebum, and hairs. Teeth were also present. Microscopically, the cyst was lined by mature epidermis with skin appendages, neural tissue and adipocyte (Fig. 2). After surgical resection of the teratoma, the hemoglobin level stopped decreasing, and it then gradually increased (Fig. 3). She was diagnosed as having AIHA induced by an ovarian teratoma. She did not have any evidence of hemolysis and anemia, but the direct antiglobulin test was still positive 4 months after the surgery.

Fig. 2.

Stratified squamous epithelium with skin appendage including sebaceous glands and hair follicle are noted (A, H & E, ×200). Neural tissue and adipocytes are present (B, H & E, ×100).

Fig. 3.

Laboratory data after admission.

DAT, direct antiglobulin test; IAT, indirect antiglobulin test.

DISCUSSION

The etiological causes of AIHA are variable. Common causes are various drugs, systemic lupus erythematosus and hematologic malignancies (7), yet teratoma has rarely been associated with AIHA. The mechanism of hemolysis is not currently defined, although several hypotheses have been proposed such as cross-reactivity of tumor and RBC antigens, production of RBC auto-antibodies by the tumor or alteration of the RBC molecules by the tumor, which renders them antigenic to the host (4, 5).

The features of AIHA associated ovarian dermoid cyst or teratoma are palpable abdominal mass and severe anemia (4). Our case had a huge ovarian teratoma; however we could not find it on the gynecologic examination. Hepatosplenomegaly is also the feature of AIHA, and this patient displayed hepatosplenomegaly on the abdominal computed tomography. The patient also had a fever at the time of diagnosis, and we could not find any infection foci, and no organism was grown during the the blood culture study. So we thought that the fever was also the phenomenon of severe hemolysis (7).

Glucocorticoids and splenectomy are the treatment of choice of AIHA; however, these were ineffective for the AIHA induced by the ovarian tumor. Only tumor removal is an effective treatment (3-6). In this case, the patient did not respond to the corticosteroid therapy, so we stopped the corticosteroid therapy and performed tumor resection; after the surgery, hemoglobin level slowly increased. However the antiglobulin antibody still persisted 4 months after tumor resection. The auto-antibodies persisted from 2 weeks to 10 months in the previous case reports (3-5). In the AIHA, blood transfusions should be avoided; however they should never be withheld from those patients in extremis (7). Our case was refractory to corticosteroid therapy, the hemoglobin level decreased and she complained of resting chest discomfort, so we performed transfusion in spite of positive cross matching, and no complications of transfusion occurred. Moreover transfusions were performed in the other case reports.

AIHA induced by teratoma is a very rare paraneoplastic phenomenon. The only effective treatment is the tumor removal, so it is important to include ovarian tumor such as teratoma in differential diagnosis of AIHA, especially the case of refractory to glucocorticoid therapy.

References

- 1.Jung CK, Park JS, Lee EJ, Kim SH, Kwon HC, Kim JS, Roh MS, Yoon SK, Kim KH, Han JY, Kim HJ. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with primary ovarian non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:294–296. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sallah S, Sigounas G, Vos P, Wan JY, Nguyen NP. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: characteristics and significance. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1571–1577. doi: 10.1023/a:1008319532359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glorieux I, Chabbert V, Rubie H, Baunin C, Gaspard MH, Guitard J, Duga I, Suc A, Puget C, Robert A. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with a mature ovarian teratoma. Arch Pediatr. 1998;5:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(97)83466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobo F, Pereira A, Nomdedeu B, Gallart T, Ordi J, Torne A, Monserrat E, Rozman C. Ovarian dermoid cyst-associated autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a case report with emphasis on pathogenic mechanisms. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:567–571. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.5.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonanno G, Gonnella F, Pettinato G, Castaldo C. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and dermoid cyst of the mesentery. A case report. Cancer. 1984;54:2533–2536. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:11<2533::aid-cncr2820541137>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young RH. New and unusual aspects of ovarian germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1210–1224. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neff AT. Autoimmune hemolytic anemias. In: Greer JP, Foerster J, Lukens JN, Rodgers GM, Paraskevas F, Glader B, editors. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. 2nd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2004. pp. 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spira MA, Lynch EC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and carcinoma: An unusual association. Am J Med. 1979;67:753–758. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]