Abstract

It is still not clear how organisms regulate the size of appendages or organs during development. During development, Dictyostelium discoideum cells form groups of ∼2 × 104 cells. The cells secrete a protein complex called counting factor (CF) that allows them to sense the local cell density. If there are too many cells in a group, as indicated by high extracellular concentrations of CF, the cells break up the group by decreasing cell-cell adhesion and increasing random cell motility. As a part of the signal transduction pathway, CF decreases the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase to decrease internal glucose levels. CF also decreases the levels of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and increases the levels of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate. In this report, we focus on how a secreted signal used to regulate the size of a group of cells regulates many basic aspects of cell metabolism, including the levels of pyruvate, lactate, and ATP, and oxygen consumption.

Key words: Dictyostelium discoideum, size regulation, pyruvate, lactate, ATP, oxygen consumption

The molecular mechanisms used by organisms to regulate the size of multicellular structures during development are poorly understood.1,2 The social amoebae Dictyostelium discoideum provides an excellent model system to study multicellular structure size regulation. Dictyostelium is a haploid organism that divides by binary fission. Dictyostelium cells grow on soil surfaces and feed on bacteria as individual amoebae when the food source is ample.3,4 Upon starvation, a developmental program is initiated and they aggregate in dendritic streams to form a multicellular structure called a fruiting body that, in our laboratory strains, tends to contain ∼20,000 cells.

The aggregating cells form a fruiting body consisting of a roughly spherical spore mass held up off the soil by a thin stem of stalk cells. The whole purpose of the formation of these structures is to disperse the spores. When a fruiting body is too small, the spore mass will be too close to the ground for optimal spore dispersal. On the other hand, if a spore mass is too big, it will slide down the stalk or the fruiting body will fall over. Therefore, it is important for Dictyostelium cells to form a fruiting body that is the right size.3,5–7 This report will discuss some of what we know about the Dictyostelium size regulation mechanism.

There seems to be three mechanisms that determine the size of the group of cells that forms a Dictyostelium fruiting body.11 The first mechanism alters the size of the aggregation territory by modifying the range of relayed signals of cAMP.12–15 The second mechanism can be observed when cells are forming aggregation streams. If the cell density is high, as aggregation streams flow into an aggregation center, the streams break into groups and each group then forms a fruiting body.16 We previously identified an ∼450 kDa secreted protein complex that affects the formation of aggregation streams, which we named counting factor (CF).9,11 The third mechanism acts after groups are formed. Even after CF-mediated stream break up, if a group is above a threshold size, it will break into smaller subgroups.17,18

CF contains at least four different proteins: countin, CF45-1, CF50 and CF60.9,19–22 Disrupting the genes encoding countin, CF45 and CF50 causes cells to secrete almost no detectable CF activity.21,22 The streams formed by countin−, cf45-1− or cf50− cells do not break up, and the unbroken streams then coalesce into huge groups.

To begin to explore what parameters of cell behavior might cause a stream of cells to break up into groups as opposed to remaining intact, we created computer simulations of streams of cells.11,23–25 The simulations suggested that if CF increases random motility and/or decreases cell-cell adhesion, a large stream of cells would begin to dissipate, and the dissipated cells would then condense into groups. We found that, as predicted, CF increases random motility, and that decreasing motility with drugs that disrupt the cytoskeleton causes the formation of large groups.10,11,19,23,24,26 Also as predicted, we found that CF decreases cell-cell adhesion, and that decreasing adhesion using antibodies to block adhesion molecules decreases group size.10,11,19,23,24,26

Garrod and Ashworth27 showed that wild-type cells grown with a high concentration (86 mM) of glucose formed larger fruiting bodies than control cells. To our surprise, we found that CF decreases intracellular glucose levels, which in turn regulate adhesion and motility to modulate fruiting body size in Dictyostelium.10 Adding glucose to cells blocks the effects of CF and mimics the effects of depleting CF on group size, adhesion and motility.

High levels of CF decrease glycogen levels, but CF does not affect the activities of amylase or glycogen phosphorylase, enzymes that break down glycogen to eventually produce glucose.28 A mutant with a disruption in glycogen synthesis does not have altered glucose levels or altered development, suggesting that CF does not regulate glycogen synthesis or breakdown to regulate glucose levels or group size.28 CF does not appear to regulate glucose by altering the activities of hexokinase, phosphofructokinase or fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, but does inhibit the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase, and the decreased activity can roughly account for the decrease in the amount of glucose in cells.28,29 Probably because of the decreased activity of glucose-6-phosphatase, CF increases levels of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate.28 For unknown reasons, CF decreases levels of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate.28 Together, these results indicated that CF regulates cell-cell adhesion and motility, and thus group size, by regulating a key enzyme in the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway.

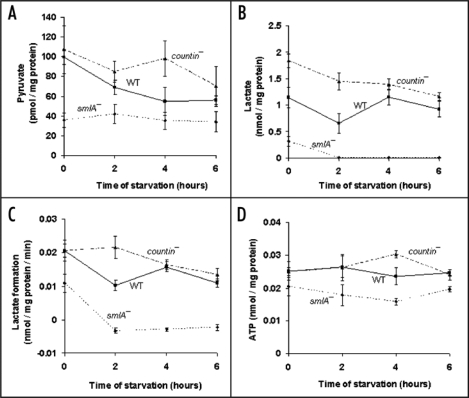

Glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate are downstream of glucose in the glycolytic pathway, which yields pyruvate and lactate. These compounds can be further metabolized in the TCA cycle.30 Conversely, amino acids can be metabolized to produce lactate and pyruvate, and these can be used to make glucose by gluconeogenesis. To elucidate the extent to which CF affects other aspects of metabolism, we measured the levels of key intermediates, such as pyruvate, at the end of the glycolysis pathway/beginning of the gluconeogensis pathway (Fig. 1A). Other workers observed that the concentration of pyruvate was 50 µM in packed vegetative wild-type cells.31 Converting our data, we obtained ∼35 µM pyruvate in packed vegetative (0 hour) wild-type cell pellets, indicating that our observations are roughly consistent with the previously observed value. During the first 4 hours of development, countin− cells (with essentially no extracellular CF activity) had significantly higher levels of pyruvate than smlA− cells (which over secrete CF) (Fig. 1A). The pyruvate levels in wild-type cells were between the countin− and the smlA− levels. These data suggest that, to a first approximation, CF decreases pyruvate levels.

Figure 1.

Cells with different levels of extracellular CF have different levels of pyruvate, lactate, lactate formation in lysates, and ATP. countin−, wild-type (WT) and smlA− cells were starved by shaking in PBM, harvested at the times indicated, and the levels of metabolites were measured in the three cell lines. (A) Pyruvate levels. At 0 hours, the differences between smlA− and WT cells, and between smlA− and countin− cells were significant. At 2 hours of starvation, the difference between smlA− and countin− cells was significant. In addition, a t-test indicated that the difference at 4 hours between smlA− and countin− cells was significant. Values are means ± SEM from at least 4 independent assays. (B) Lactate levels. The measured values of lactate in smlA− cells at 2, 4 and 6 hours of starvation were 8.9 ± 7.7, 5.9 ± 6.0 and 9.7 ± 8.4 pmol/mg protein, respectively. At 0 and 2 hours, the differences between smlA− and WT, WT and countin−, and smlA− and countin− cells were significant. At 4 and 6 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, and smlA− and countin− cells were significant. Values are means ± SEM from at least 6 independent assays. (C) The formation of lactate in lysates. The negative values for smlA− at 2, 4 and 6 hours indicate that lactate was used faster than it was made. At 0 hours, the difference between smlA− and WT lysates was significant, and at 2 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, WT and countin−, and smlA− and countin− lysates were significant. At 4 and 6 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, and smlA− and countin− lysates were significant. Values are means ± SEM from 6 independent assays. (D) ATP levels. At 4 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, WT and countin−, and smlA− and countin− cells were significant. At 6 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, and smlA− and countin− cells were significant. Values are means ± SEM from five independent assays.

Pyruvate can easily be converted to lactate during glycolysis, or vice versa during gluconeogenesis.30 Because the levels of pyruvate appeared to be affected by extracellular CF, we measured the levels of lactate. Other workers found that the amount of lactate in Ax2 cells is 1.7–2.4 nmol/mg protein and 0.3–1.0 nmol/mg protein at 0 and 4 hours of starvation, respectively.32 The levels of lactate we measured in wild-type cells were in rough agreement with the previously observed values (Fig. 1B). From 0 to 6 hours, lactate levels were the highest in countin− cells, intermediate in wild-type cells, and the lowest in smlA− cells (Fig. 1B). This suggests that, as with pyruvate, CF decreases lactate levels.

While measuring lactate levels, we noticed that the lactate levels in the thawed lysates changed with time (Fig. 1C), and we thus found that it is important to measure lactate levels quickly. In the vegetative cell lysates, more lactate was being formed in countin− and wild-type lysates compared to smlA− lysates. During development, the levels of lactate decreased in smlA− lysates, indicating that lactate was being consumed. Wild-type lysates appeared to be making lactate, and countin− lysates made slightly more lactate compared to the wild-type lysates. Together, the data indicate that both the rate of lactate production and the levels of lactate are decreased by CF in lysates.

Since the levels of glucose, pyruvate and lactate seemed to be repressed by CF, and since these altered levels may reflect an altered rate of either glycolysis or gluconeogenesis, we examined levels of ATP, a key product of metabolism. Converting our data, we obtained ∼5 µM ATP in wild-type cells during vegetative growth and the first six hours of development (Fig. 1D). This is considerably lower than the previously observed ATP levels of 0.93 mM, which were only measured during late development, using cells grown on bacteria.33,34 During the first two hours of development, the levels of ATP were similar between countin− and wild-type, and slightly less in smlA− cells (Fig. 1D). At four hours, compared to wild-type, countin− cells had significantly higher levels of ATP, and smlA− cells had significantly lower levels of ATP (Fig. 1D). At six hours, the ATP levels in countin− and wild-type cells were similar, and the ATP levels in smlA− cells were lower. Together, the data suggest that high levels of CF tend to decrease ATP levels.

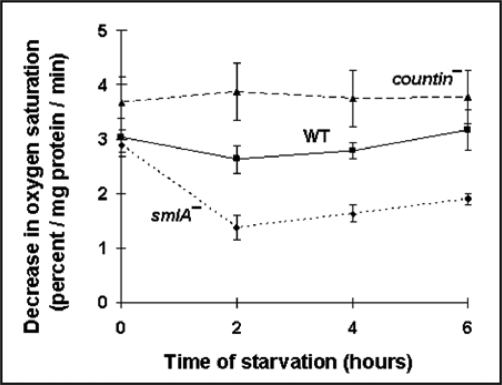

Since cells mostly use oxygen during oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP, we measured oxygen consumption in the three different cell lines. During vegetative growth, the rates of oxygen consumption were similar in smlA−, wild-type and countin− cells (Fig. 2). At two and four hours, compared to wild-type, the rate of oxygen consumption was significantly higher in countin−, and significantly lowers in smlA− cells. The observations that the levels of ATP and oxygen consumption were low in smlA− cells and high in countin− cells suggest that CF represses oxidative phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Cells with different amounts of extracellular CF have different levels of oxygen consumption. countin−, wild-type and smlA− cells were starved by shaking in PBM, and harvested at the times indicated. The oxygen consumption was then measured; a high decrease in oxygen saturation corresponds to a high O2 utilization by cells. At 2 and 4 hours of starvation, the differences between smlA− and WT, WT and countin−, and smlA− and countin− cells were significant with p < 0.05. Values are means ± SEM from three independent assays.

In Dictyostelium, glucose stimulates oxygen consumption.35 It is thus possible that the repression of glucose levels by CF may play a role in decreasing oxygen consumption and ATP levels. In addition, low glucose levels caused by CF could cause a low flux through the glycolytic pathway, resulting in the observed low levels of lactate and pyruvate in cells with high extracellular levels of CF. Alternatively, CF could conceivably decrease amino acid influx to the gluconeogenic pathway, which would result in a decrease in the levels of glucose, pyruvate, lactate, ATP and the rate of oxygen consumption.

Conclusion

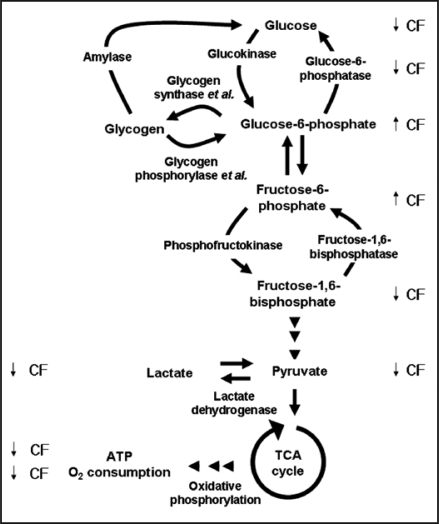

Combined with our previous observations that CF decreases glucose and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate levels, and increases fructose-6-phosphate and glucose-6-phosphate levels, our findings suggest that CF regulates basic cellular metabolism, such as pyruvate, lactate and ATP, and the rates of oxygen consumption in cells and lactate formation in lysates (Fig. 3, reviewed in refs. 10 and 28).

Figure 3.

The effects of CF on metabolism. Glycogen phosphorylase and glycogen synthase catalyze part of the reactions that are shown in the drawing, and are therefore noted as enzyme et al. The levels of glucose, glucose- 6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate were measured by Jang et al.22 and Jang and Gomer.28 The arrows indicate the effects of CF on the levels of each intermediates or metabolites (up arrow for increasing the levels, and down arrow for decreasing the levels).

Unlike the levels of glucose, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, pyruvate, lactate, ATP, and the rate of oxygen consumption, the levels of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate were increased by CF (Fig. 3 and reviewed in ref. 28). The CF-induced decrease in the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase can account for the decrease in glucose levels when cells are exposed to CF.28,29 However, the CF-induced increase in glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate levels compared to the CF-induced decrease in fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, pyruvate, lactate and ATP levels suggests that CF regulates the activity of a second enzyme.

There are several possible reasons why CF might regulate metabolism. One is that an ancestral motile cell evolved a mechanism to regulate adhesion and motility based on the availability of food, as sensed by some combination of glucose and ATP levels. If the cell found itself in the presence of ample food, as indicated by high internal glucose and ATP levels, it would decrease cell motility and increase adhesion to stay in place. When the cell began to starve, as indicated by low glucose and ATP levels, it would increase cell motility and decrease adhesion to move to a new location. It is possible that this simple mechanism may have, during evolution, become modulated by the CF signal to regulate group size, while the overall glucose metabolism is affected by CF.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture.

Dictyostelium discoideum Ax4 wild-type, smlA− clone HDB7YA, and cells with a disruption of the ctnA gene (strain HDB2B/4; referred to in this and previous work as countin− cells) were grown in HL5 media (with maltose as the carbohydrate source) and starved in PBM (20 mM KH2PO4, 10 µM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 [pH 6.1] with KOH) buffer at 5 × 106 cells/ml as previously described.8–10 Cells were collected as previously described.10 For freeze lysis, the pellets were lysed by freezing at −70°C for 2 or more hours, and were then thawed. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 19,000 xg for 1 minute.

Pyruvate, lactate and ATP assays.

Pyruvate, lactate and ATP assays were performed using pyruvate, lactate and ATP assay kits (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) following the user's manuals. At 0, 2, 4 and 6 hours after starvation, 10 ml of cells in shaking culture were collected and lysed by freeze lysis. For pyruvate assays, 550 µl of PBM was added to the pellets, and the lysates were clarified. Five hundred micoliters of lysate was mixed with 1.5 ml of 8% perchloric acid, and used for the assay. For lactate assays, 200 µl of PBM was added to the pellets, and 100 µl of clarified cell lysate was used for the assay. The amount of lactate in the lysates was measured at 5-minute intervals. For ATP assays, 350 µl of PBM was added to the pellets, and 300 µl of cell lysate was used for the assay. For all assays, 2 µl of the clarified lysate was used at the same time for a Bio-Rad protein assay, using BSA as a standard.

Oxygen consumption assay.

One milliliter of cells starved in shaking culture was collected at 0, 2, 4 and 6 hours of starvation, and diluted to 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in PBM. 1.2 ml of the cell suspension was placed in the chamber of a model 5300 biological oxygen monitor (Yellow Springs Instrument, Yellow Springs, OH) while constantly stirring the cell suspension using a plastic-coated magnetic stir bar, at a slow rate to prevent severe agitation or bubble formation. The oxygraph was calibrated using the O2 concentration of PBM in the absence of cells as 100% saturation.

Statistics.

All statistics were done with Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). One-way ANOVA using Tukey's multiple comparison test as a post-test was done to compare values from three different cell lines. Where indicated, t-tests were also done. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

Richard H. Gomer was an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported in part by the Dongguk University research fund of 2009 and by NIH GM074990.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- Ax4

axenic strain 4

- CF

counting factor

- PBM

phosphate buffer with magnesium

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/8470

References

- 1.Gomer RH. Not being the wrong size. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:48–54. doi: 10.1038/35048058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamer L, Nove J, Rosen V. Return of the Chalones. Dev Cell. 2003;4:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loomis WF. Dictyostelium discoideum: A developmental system. New York: Acad Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessin RH. Dictyostelium Evolution, cell biology and the development of multicellularity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firtel RA. Integration of signaling information in controlling cell-fate decisions in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1427–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaap P. Intercellular interactions during Dictyostelium development. In: Dworkin M, editor. Microbial Cell-Cell Interactions. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol; 1991. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devreotes P. Dictyostelium discoideum: A model system for cell-cell interactions in development. Science. 1989;245:1054–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.2672337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock DA, Buczynski F, Spann TP, Wood SA, Cardelli J, Gomer RH. A Dictyostelium mutant with defective aggregate size determination. Development. 1996;122:2569–2578. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock DA, Gomer RH. A cell-counting factor regulating structure size in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1960–1969. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang W, Chiem B, Gomer RH. A secreted cell-number counting factor represses intracellular glucose levels to regulate group size in Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31972–31979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roisin-Bouffay C, Jang W, Gomer RH. A precise group size in Dictyostelium is generated by a cell-counting factor modulating cell-cell adhesion. Mol Cell. 2000;6:953–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedel V, Gerisch G, Muller E, Beug H. Defective cyclic adenosine-3,5′-phosphate-phosphodiesterase regulation in morphogenetic mutants of Dictyostelium discoideum. J Mol Biol. 1973;74:573–585. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thadani V, Pan P, Bonner JT. Complementary effects of ammonia and cAMP on aggregation territory size in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. ExpCell Res. 1977;108:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faure M, Podgorski GJ, Franke J, Kessin RH. Disruption of Dictyostelium discoideum morphogenesis by overproduction of cAMP phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8076–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Y, Gomer RH. A protein with similarity to PTEN regulates aggregation territory size by decreasing cyclic AMP pulse size during Dictyostelium discoideum development. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1758–1770. doi: 10.1128/EC.00210-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer BM. Variability of behavior of aggregating cellular slime moulds. Quart J Micr Sci. 1957;98:393–405. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohl HR, Raper KB. Control of sorocarp size in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Biol. 1964;9:137–153. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopachik WJ. Size regulation in Dictyostelium. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;68:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brock DA, Ehrenman K, Ammann R, Tang Y, Gomer RH. Two components of a secreted cell-number counting factor bind to cells and have opposing effects on cAMP signal transduction in Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52262–52272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brock DA, van Egmond WN, Shamoo Y, Hatton RD, Gomer RH. A 60-kilodalton protein component of the counting factor complex regulates group size in Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1532–1538. doi: 10.1128/EC.00169-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brock DA, Hatton RD, Giurgiutiu D-V, Scott B, Ammann R, Gomer RH. The different components of a multisubunit cell number-counting factor have both unique and overlapping functions. Development. 2002;129:3657–3668. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brock DA, Hatton RD, Giurgiutiu D-V, Scott B, Jang W, Ammann R, et al. CF45-1, a secreted protein which participates in group size regulation in Dictyostelium. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:788–797. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.4.788-797.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang W, Gomer RH. Combining experiments and modelling to understand size regulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5:49–58. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0067.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang L, Gao T, McCollum C, Jang W, Vickers MG, Ammann R, et al. A cell number-counting factor regulates the cytoskeleton and cell motility in Dictyostelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1371–1376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022516099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dallon J, Jang W, Gomer RH. Mathematically modelling the effects of counting factor in Dictyostelium discoideum. Math Med Biol. 2006;23:45–62. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqi016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao T, Roisin-Bouffay C, Hatton RD, Tang L, Brock DA, DeShazo T, et al. A cell number-counting factor regulates levels of a novel protein, SslA, as part of a group size regulation mechanism in Dictyostelium. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1538–1551. doi: 10.1128/EC.00169-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrod DR, Ashworth JM. Effect of growth conditions on development of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum. J Embryol Exp Morph. 1972;28:463–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang W, Gomer RH. Exposure of cells to a cell-number counting factor decreases the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase to decrease intracellular glucose levels in Dictyostelium. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:991–998. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.1.72-81.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang W, Gomer RH. A protein in crude cytosol regulates glucose-6-phosphatase activity in crude microsomes to regulate group size in Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16377–16383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509995200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehninger A, Nelson D, Cox M. Principles of Biochemistry. New York, NY: Worth Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleland SV, Coe EL. Conversion of aspartic acid to glucose during culmination in Dictyostelium discoideum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;192:446–454. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schachner E, Aschhoff H-J, Kersten H. Specific changes in lactate levels, lactate dehydrogenase patterns and cytochrome b559 in Dictyostelium discoideum caused by queuine. FEBS Lett. 1984;139:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutherford CL, Wright BE. Nucleotide metabolism during differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:269–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.269-275.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson JB, Rutherford CL. ATP, trehalose, glucose and ammonium ion localization in the two cell types of Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Physiol. 1978;94:37–48. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040940106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liddel G, Wright B. The effect of glucose on respiration of the differentiating slime mold. Dev Biol. 1961;3:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(61)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]