Abstract

Background

Potassium currents contribute to action potential duration (APD) and arrhythmogenesis. In heart failure, Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is upregulated and can alter ion channel regulation and expression.

Methods and Results

We examine the influence of overexpressing cytoplasmic CaMKIIδC, both acutely in rabbit ventricular myocytes (24 h adenoviral gene transfer) and chronically in CaMKIIδC-transgenic mice, on transient outward potassium current (Ito), and inward rectifying current (IK1). Acute and chronic CaMKII overexpression increases Ito,slow amplitude and expression of the underlying channel protein KV1.4. Chronic, but not acute CaMKII overexpression, causes down-regulation of Ito,fast, as well as KV4.2 and KChIP2, suggesting that KV1.4 expression responds faster and oppositely to KV4.2 upon CaMKII activation. These amplitude changes were not reversed by CaMKII inhibition, consistent with CaMKII-dependent regulation of channel expression and/or trafficking. CaMKII (acute and chronic) greatly accelerated recovery from inactivation for both Ito components, but these effects were acutely reversed by AIP (CaMKII inhibitor), suggesting that CaMKII activity directly accelerates Ito recovery. Expression levels of IK1 and Kir2.1 mRNA were downregulated by CaMKII overexpression. CaMKII acutely increased IK1, based on inhibition by AIP (in both models). CaMKII overexpression in mouse prolonged APD (consistent with reduced Ito,fast and IK1), while CaMKII overexpression in rabbit shortened APD (consistent with enhanced IK1 and Ito,slow and faster Ito recovery). Computational models allowed discrimination of contributions of different channel effects on APD.

Conclusion

CaMKII has both acute regulatory effects and chronic expression level effects on Ito and IK1 with complex consequences on APD.

Keywords: action potentials, potassium, arrhythmia, electrophysiology, heart failure

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is accompanied by arrhythmogenic changes related to electrical remodeling. This is associated with prolongation of action potential duration (APD)1 and down-regulation of transient outward K-current (Ito) and inward rectifying K-current (IK1). IK1 is responsible for stabilizing the diastolic membrane potential (Em), such that decreased IK1 increases the propensity for triggered arrhythmias.2 Ito is important in early repolarization and influences the effects of other currents and transporters by affecting AP voltage-time trajectory. There are at least two components of Ito generated by different K-channel isoforms, which can be distinguished according to their recovery and inactivation kinetics.3, 4 The fast component (Ito,fast) recovers and inactivates with time constants (τ) of <100 ms, whereas the slow component (Ito,slow) recovers with τ of hundreds of milliseconds up to several seconds and inactivates with τ of ~200 ms.3–5 Downregulation of Ito has been described in animal models of hypertrophy and human HF, 2, 6, 7 is associated with APD prolongation8 and predisposes to early after-depolarizations.

In HF, expression and activity of Ca/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) are enhanced.9–11 CaMKIIδ is the predominant cardiac isoform12 and transgenic mice (TG) overexpressing cytosolic CaMKIIδC develop HF with increased APD13 and are prone to ventricular arrhythmias.14 Recent evidence suggests that chronic inhibition of CaMKII results in APD shortening15 and prevents remodeling after myocardial infarction and excessive β-adrenergic stimulation.16 Moreover, an enhancement of Ito and inward rectifying IK1 after chronic CaMKII inhibition was described, whereas acute CaMKII-inhibition did not increase Ito and IK115.

We studied how CaMKII alters Ito and IK1, both acutely by adenoviral CaMKII overexpression in rabbit myocytes and chronically in CaMKII TG mice. We found that CaMKII activation exerts an acute regulatory effect on Ito and IK1, and that CaMKII causes opposite effects on functional expression of Ito,slow and Ito,fast, whereas functional expression of IK1 was only downregulated after TG CaMKII overexpression.

Methods

CaMKIIδC TG mice and overexpression of CaMKIIδC in rabbit myocytes

CaMKIIδC TG mice were used at 17.6±2.3-weeks of age17 and compared to their age- and sex-matched wild-type (WT) littermates. Ventricular myocytes were isolated18 and kept in modified Tyrode solution containing (mmol/l) 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 Na2HPO4, 20 HEPES, 15 glucose, 1 CaCl2 (pH 7.4). Ventricular myocytes were isolated from rabbits (1.3–2.0 kg).19 Transfection with CaMKIIδC adenovirus (Ad-CaMKIIδC) was performed and compared to β-galactosidase (Ad-βGal) as a control at a MOI of 100.18, 20 Cells were cultured for 24 h with M199 and washed prior to the experiment.18 All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

An expanded Materials and Methods section can be found in the online data supplement.

Results

Functional expression and inactivation kinetics of Ito

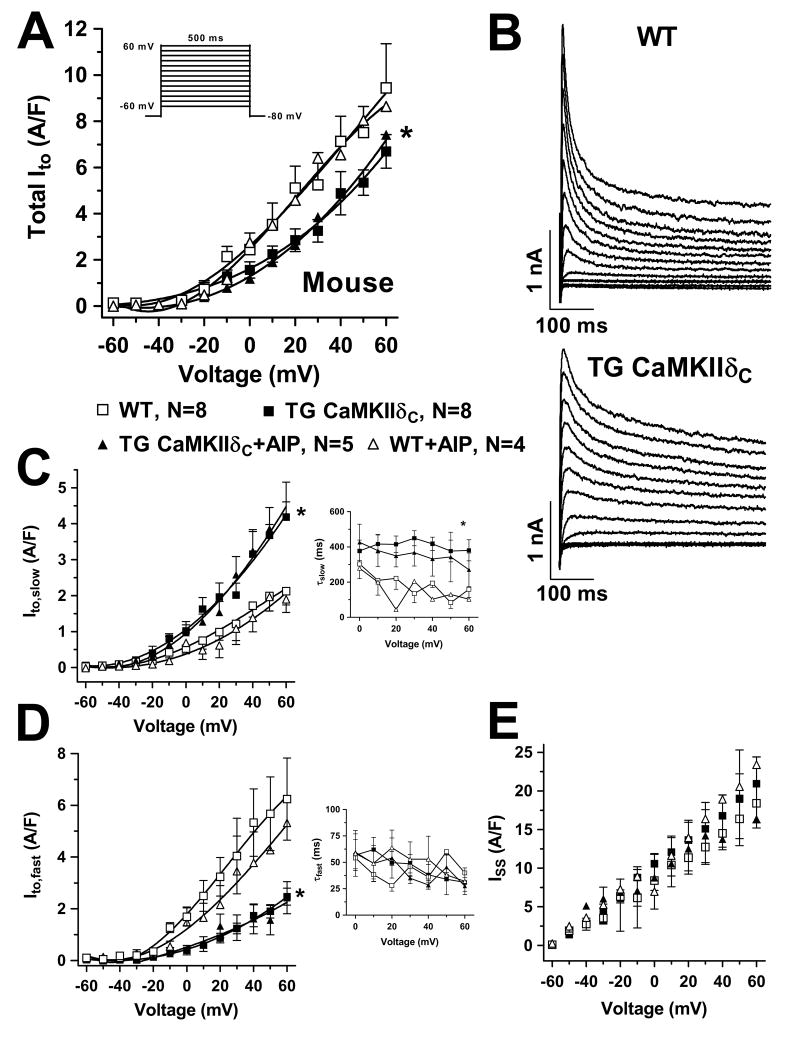

To measure CaMKIIδC-dependent regulation of Ito, the Em-dependence of activation and the kinetics of inactivation were analyzed (Figure 1–2). Ito,fast and Ito,slow were separated based on inactivation rate. Original traces were fit to bi-exponentials to obtain amplitudes and time constants τfast and τslow of inactivation.3, 21 In CaMKIIδC TG mice, total Ito was significantly reduced (vs. WT, Fig 1A), due to a large reduction in Ito,fast with a slightly smaller increase in Ito,slow (Fig 1C–D).

Figure 1.

Ito current-voltage relation in mouse myocytes. (A) Mean data of total Ito which was significantly reduced in TG. (B) Original records. (C) Ito,slow amplitude was enhanced in TG but not reversed with AIP. Time constant of Ito,slow inactivation was slowed (right), but not reversed by AIP. (D) The reduction of total Ito was based on a smaller Ito,fast in TG and not influenced by AIP. The time constant of Ito,fast inactivation was not altered (right). (E) Steady-state currents were not affected. Average maximum Ito: 1.85±0.15 nA, 7.82±0.77 pA/pF, Cm 257±18.6 pF, RS 8.5±0.6 MΩ. *P<0.05 vs. WT (ANOVA).

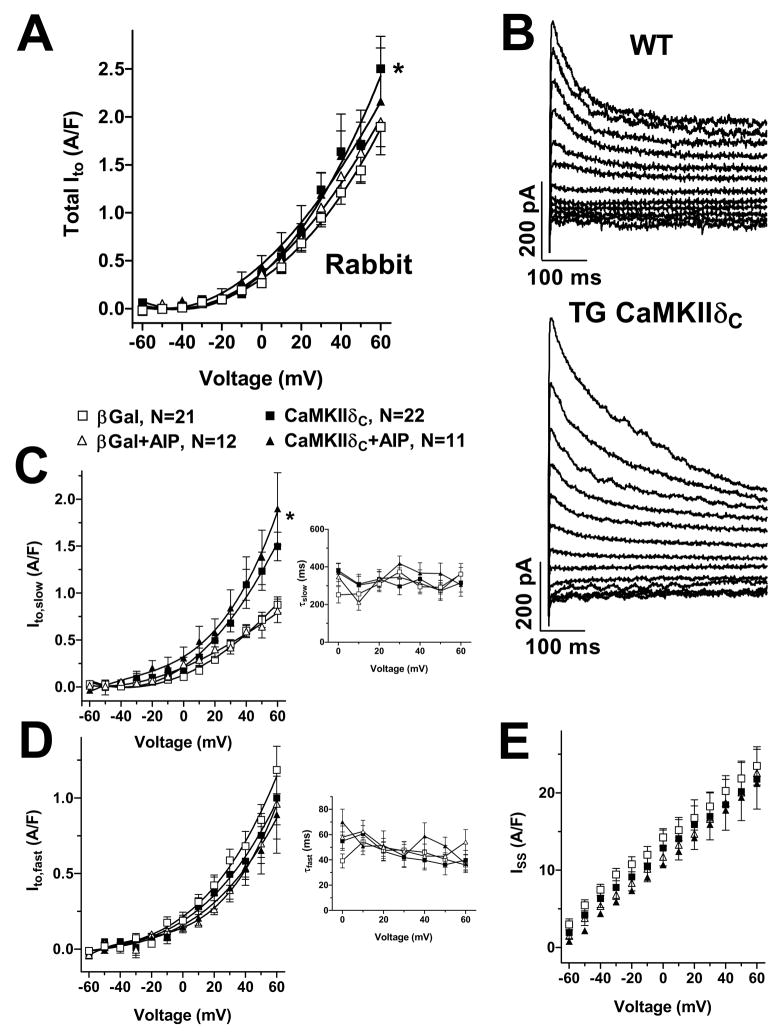

Figure 2.

Ito current-voltage relation in rabbit myocytes. (A) Mean data of total Ito. (B) Original records. (C) The increase of total Ito appears to be due to an increase of Ito,slow amplitude and not reversible by AIP, (D) while Ito,fast was not altered. Unchanged time constants of Ito,slow and Ito,fast inactivation (right panels). (E) Steady-state currents were not affected. Average maximum Ito: 0.32±0.03 nA, 2.12±0.16 pA/pF, Cm 151±4.8 pF, RS 8.6±0.4 MΩ. *P<0.05 vs. βGal (ANOVA).

In CaMKIIδC mice, neither the Em-dependence of Ito activation (both Ito components), nor the inactivation kinetics for Ito,fast nor the steady-state current were altered (Fig 1C–E). However, Ito,slow inactivated more slowly in the CaMKIIδC mice (Figure 1C, right). Neither the Ito amplitude effects nor the inactivation kinetic effects in CaMKIIδC mice were reversed by CaMKII-inhibition using AIP, implying that CaMKII alters functional channel (or regulator) expression.

In rabbit myocytes, CaMKIIδC-overexpression significantly enhanced total Ito (Fig 2A). This was the result of significant up-regulation of Ito,slow amplitude, without detectable alteration in Ito,fast (Fig 2C–D). No CaMKII-dependent shifts were detected in either the Em-dependence or kinetics of inactivation. Again, the CaMKII-induced changes in total Ito and Ito,slow amplitude were not reversible using AIP, suggesting that functional upregulation of Ito,slow may occur after only 24 hr of CaMKIIδC adenoviral infection.

Ito recovery from inactivation

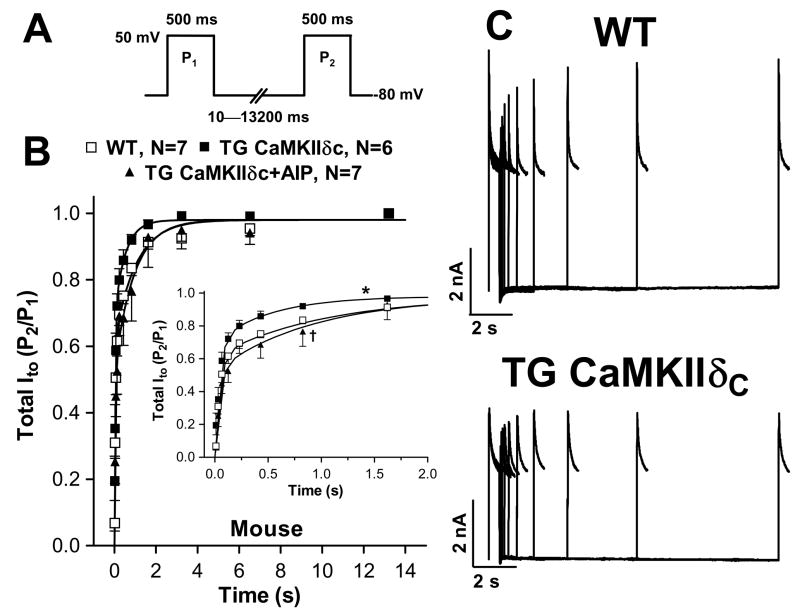

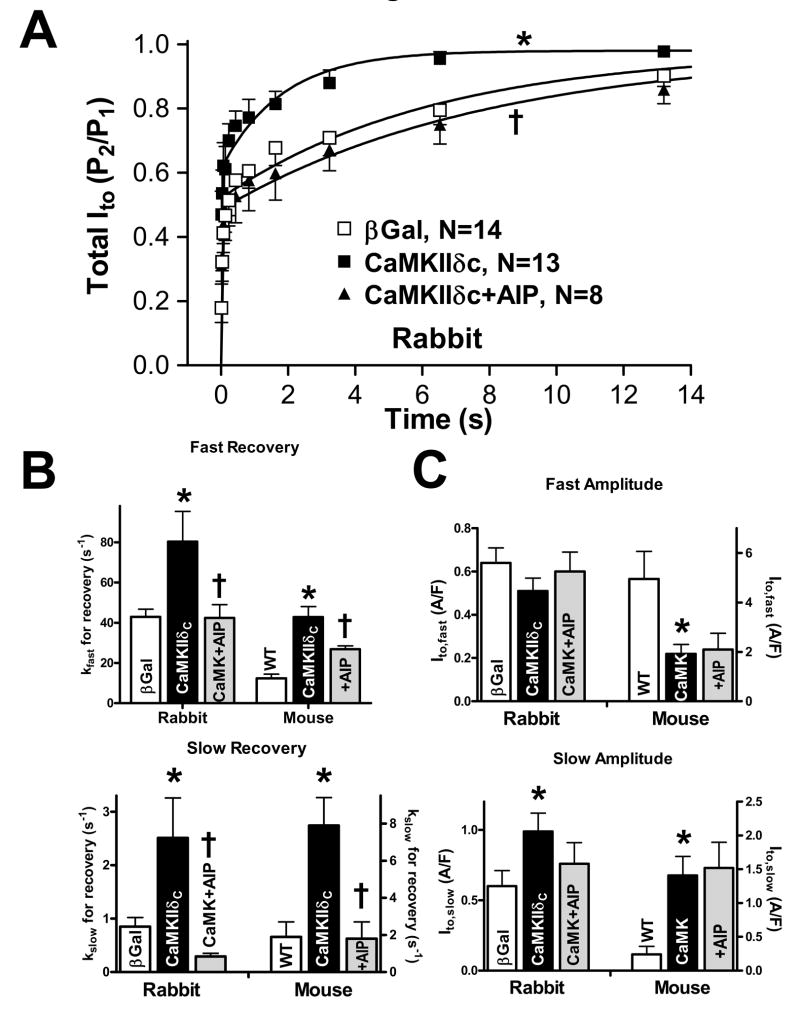

Ito recovery from inactivation was assessed using a two pulse protocol (Fig 3A). Compared to WT and β-gal control myocytes, Ito recovery from inactivation was significantly faster in CaMKIIδC-overexpressing mouse (Fig 3B–C) and rabbit (Fig 4A) myocytes. This accelerated recovery was completely reversed by AIP (Fig 4B). Recovery was bi-exponential and CaMKII accelerated both fast (kfast) and slow (kslow) recovery from inactivation, an effect reversed by AIP (Fig 4B, Table 1). Thus, CaMKII appears to acutely speed recovery of Ito,fast and Ito,slow, and this would increase Ito availability at high heart rates.

Figure 3.

Ito recovery from inactivation in mouse myocytes. (A) Protocol. (B) Mean data for total Ito. Inset shows Ito recovery within the first 2 s. Data was fit to a double exponential function (Table 1). (C) Original records. Ito recovery from inactivation was enhanced in TG vs. WT (*P<0.05, F-test) which was reversible with AIP (†P<0.05, F-test).

Figure 4.

(A) Ito recovery from inactivation in rabbit myocytes. Mean data for total Ito. *P<0.05 vs. βGal; †P<0.05 vs. CaMKIIδC (F-test) (B+C) Recovery rate constants and amplitudes of Ito,fast and Ito,slow. (B) Ito,fast and Ito,slow where significantly enhanced after CaMKII overexpression in rabbit and mouse myocytes and could be slowed using AIP. (C) After adenoviral CaMKIIδc overexpression, the amplitude of Ito,slow was significantly increased. Ito,fast was unchanged. In TG mice, Ito,slow amplitude was increased, but Ito,fast was significantly reduced. All effects were unaffected upon CaMKII inhibition. *P<0.05 vs. WT or βGal; †P<0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle (one-way ANOVA).

Table 1.

Fitting parameters for Ito recovery from inactivation

| Mouse [n] | Rabbit [n] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG CaMKIIδC [6] (WT) [7] |

TG CaMKIIδC+AIP [8] | Ad-CaMKIIδC [13] (Ad-βGal) [14] |

Ad-CaMKIIδC+AIP [8] (Ad-βGal+AIP) [8] |

|

| Afast (A/F) | 1.92±0.38* (4.95±1.12) | 2.10±0.65 | 0.51±0.06 (0.64±0.07) | 0.60±0.09 (0.76±0.22) |

| Afast/y0 | 0.71±0.07* (0.89±0.04) | 0.59±0.09 | 0.35±0.03* (0.54±0.05) | 0.45±0.04 (0.62±0.08) |

| kfast (s−1) | 42.8±5.2* (12.3±2.1) | 26.9±1.6† | 80.4±15.0* (42.9±3.8) | 42.4±6.6† (38.3±10.2) |

| Aslow (A/F) | 1.41±0.28* (0.24±0.12) | 1.52±0.38 | 0.99±0.13* (0.60±0.11) | 0.76±0.15 (0.48±0.18) |

| Aslow/y0 | 0.29±0.07* (0.11±0.05) | 0.41±0.09 | 0.63±0.03* (0.46±0.05) | 0.55±0.04 (0.38±0.08) |

| kslow (s−1) | 7.9±1.5* (1.9±0.8) | 1.8±0.9† | 2.51±0.75* (0.85±0.17) | 0.29±0.06† (0.63±0.11) |

| y0 (A/F) | 3.75±0.48 (4.90±1.29) | 4.14±0.87 | 1.46±0.15 (1.24±0.14) | 1.36±0.21 (1.24±0.3) |

Fit parameters measured in mouse (average maximum Ito 1.04±0.13 nA, 4.16±0.57 pA/pF, Cm 260±17.5 pF, RS 8.6±0.6 MΩ) and rabbit (average maximum Ito 0.21±0.02 nA, 1.3±0.1 pA/pF, Cm 160.4±5.3 pF, RS 8.7±0.5 MΩ) myocytes.. Cm=membrane capacitance, RS=series resistance.

P<0.05 vs. βGal and WT.

P<0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle.

Since Ito,fast typically inactivates and recovers faster than Ito,slow, we compared the amplitudes of Ito recovery. CaMKII significantly increased the Ito,slow proportion (Aslow/(Aslow+Afast)) and Ito,slow density in both rabbit and mouse, but this effect was not reversed by AIP (Fig 4C, Table 1). This may reflect a CaMKII-dependent increase in functional expression of Ito,slow. In contrast, Ito,fast density was not altered by CaMKII overexpression in rabbit, suggesting unaltered functional expression of Ito,fast. Conversely, CaMKIIδC mice exhibit decreased Ito,fast (Fig 4C, Table 1) which was not reversible by AIP. These conclusions match those from the inactivation kinetics (Figs 1–2) and strengthen the conclusions regarding Ito assignment to Ito,fast and Ito,slow.

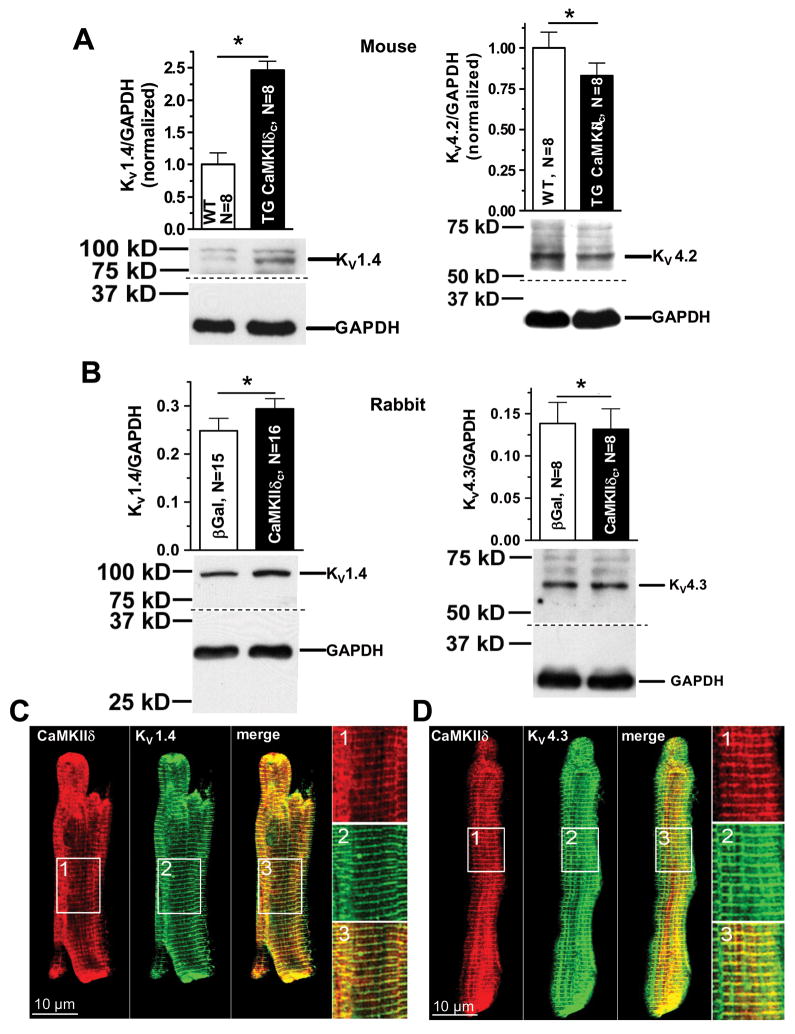

K-channel expression and co-localization of CaMKII with KV1.4, 4.2, and 4.3

To clarify whether there is a combination of altered channel expression changes (insensitive to AIP) as well as acute CaMKII modulation (reversed by AIP), we assessed mRNA and protein expression levels of the channel forming subunits thought to underlie Ito,slow (KV1.4) and Ito,fast (KV4.2/4.3) and the β-subunit KChIP2 that associates with Kv4.2/Kv4.3.

KV1.4 expression was significantly enhanced by CaMKIIδC expression in mice and rabbits overexpressing CaMKIIδC (Fig 5A–B). This agrees with the observed increase of Ito,slow that is not acutely blockable by AIP. Notably, mRNA measurements (Suppl. Fig. 1A+B) roughly paralleled this data, consistent with CaMKII-dependent transcriptional regulation.

Figure 5.

K-channel expression. (A) Western blots of KV1.4 and KV4.2 from mouse heart. (B) Western blots of KV1.4 and KV4.3 in rabbit myocytes. (C+D) Confocal microscopy using immunocytological stainings of CaMKII, KV1.4 (C), KV4.3 (D). Merge indicates the close relationship of CaMKII with KV1.4 and KV4.3. *P<0.05 (t-test)

In contrast to the enhanced KV1.4, expression, KV4.2 was significantly down-regulated in TG mice vs. WT at both protein and mRNA levels (Fig 5A and Suppl. Fig. 1), while KV4.3 expression was unaltered. The reduction of Kv4.2 protein expression was relatively small compared to the greatly reduced Ito,fast density. However, mRNA levels of KChIP2 were also reduced to about 50% in TG vs. WT (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Thus both Kv4.2 and KChIP2 decreases may contribute to the net reduction of Ito,fast density. This reduced expression of KV4.2/4.3 agrees with previously published data from failing myocardium.6, 22–24 Reduced Ito,fast generated via KV4.2/4.3 may be a general feature of cardiac remodeling in HF,25 and this might be partly caused by CaMKII.

In rabbit myocytes, CaMKIIδC failed to alter Ito,fast (Fig 2D&4C) and there was likewise no significant change in KV4.3 protein or Kv4.2 or Kv4.3 mRNA expression (Fig 5B and Suppl. Fig. 1B). There was an increase in KChIP2 mRNA levels (Suppl. Fig. 1B), but that may be unrelated to the unaltered Ito,fast amplitude.

Subcellular immunolocalization of CaMKII and K-channels (Fig 5C–D) show KV1.4, KV4.3 and CaMKII in rabbit myocytes. All proteins show a striated pattern, consistent with a co-localization in the transverse tubules.

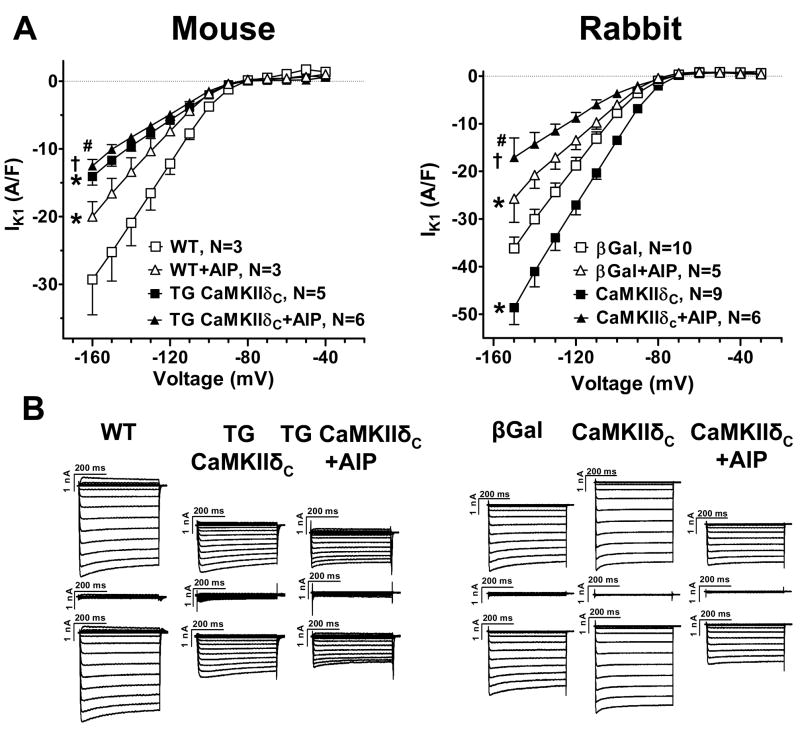

Inward rectifying current IK1

CaMKII effects on IK1 were assessed using 500 ms pulses to varying Em (I–V curves in Figure 6A). We compared IK1 (which reversed near −80 mV) using the outward current amplitudes at negative Em. Measuring IK1 in the presence of AIP showed 30–40% IK1 down-regulation upon both acute and chronic CaMKIIδC overexpression (▲ vs. △ in Fig 6). In accordance with this, Kir2.1 gene expression was downregulated by ~40% in TG mice, and the mean value was lower in CaMKIIδC rabbit myocytes (but not significantly; Suppl. Fig. 1). Thus, CaMKII downregulates IK1 expression within 24 h.

Figure 6.

IK1 current-voltage relation. (A) Mean data for peak IK1 in myocytes from TG mice (vs. WT) and rabbit CaMKIIδC myocytes (vs. βGal). *P<0.05 vs. WT and βGal; †P<0.05 vs. TG CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIδC; #P<0.05 vs. WT+AIP and βGal+AIP (ANOVA). (B) Original traces. Each upper trace is the raw current, each mid trace shows the remaining current after BaCl2, and each lower trace depicts the BaCl2 sensitive current used for analysis.

In all cases, the measured IK1 was reduced by AIP (squares vs. triangles, Fig 6A), from which we infer that there may be some basal level of CaMKII-dependent IK1 activation. In the TG mouse the AIP-sensitive component of IK1 was reduced, implying unaltered basal CaMKII-dependent regulation. However, in the rabbit, CaMKIIδC overexpression increased the AIP-sensitive IK1 by >100% despite a lower baseline. This raises the intriguing possibility that short-term enhancement of CaMKII can activate IK1. These changes were seen both in the inward component as well as the small but physiologically relevant outward component of IK1 (not shown).

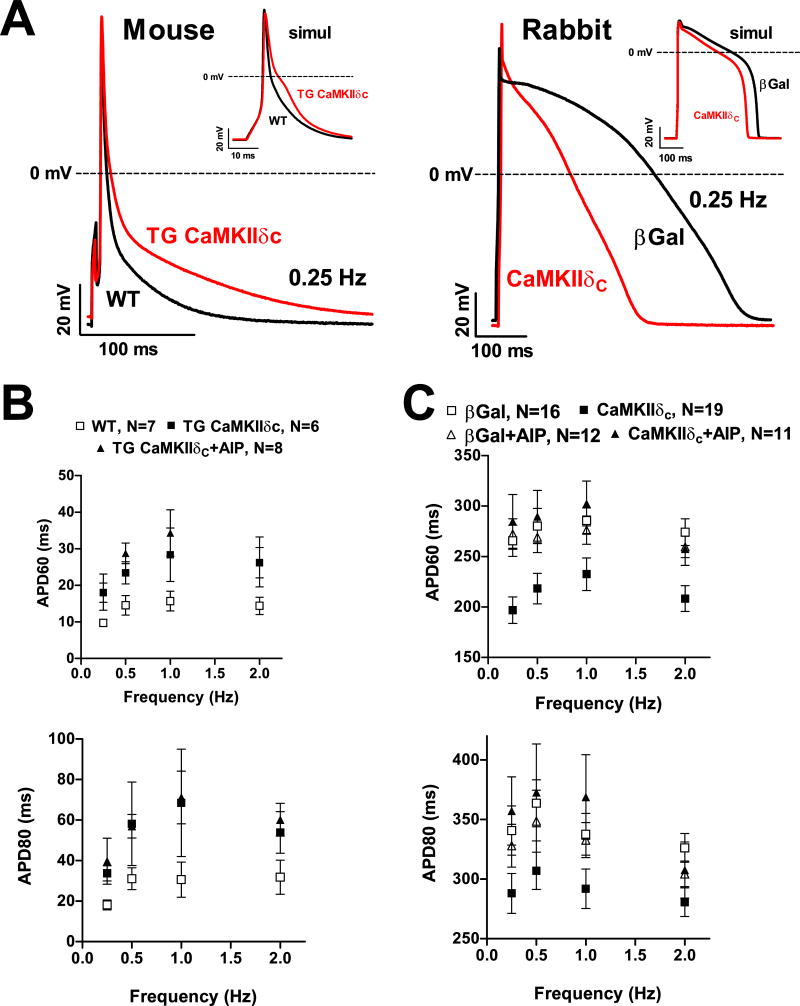

APD and computational modeling

Figure 7A–B show that in CaMKIIδC TG mice, APD was significantly prolonged over a broad range of frequencies, and that AIP did not reverse the effect. This result is consistent with the reductions in Ito,fast, total Ito and IK1, which would all be expected to prolong APD. The lack of effect of AIP is consistent with the APD prolongation being due to the reduced expression of KV4.2, KChIP2 and Kir2.1, rather than the acute CaMKII-dependent acceleration of Ito recovery.

Figure 7.

AP measurements. (A) Original traces at 0.25 Hz in mouse and rabbit myocytes. Insets show simulated traces at 0.25 Hz. (B+C) Mean data of APD at 60% (APD60) and 80% (APD 80) for 0.25–2 Hz. (B) Compared to WT, APDs were prolonged in TG; AIP did not influence APDs. (C) APDs were shorter in CaMKIIδC-overexpressing rabbit myocytes vs.βGal; AIP re-lengthened APDs.

In striking contrast, rabbit APD was significantly shortened by acute CaMKIIδC over-expression (vs. β-Gal), and this effect was largely reversed by AIP (Fig 7A&C). The APD shortening could be partly due to the CaMKII-induced enhancement of total Ito and Ito,slow amplitude (Figs 2C&4C) and higher KV1.4 expression (Fig 5B), but that should not be AIP-sensitive. A more likely dominant explanation could be the CaMKII-induced acceleration of Ito recovery from inactivation (Fig 4B), which would increase Ito density during the AP. This would be especially the case for Ito,slow which takes several seconds to recover in the absence of CaMKII but where CaMKII doubles the rate of recovery (Fig 4A–B). A third explanation is the CaMKII-dependent increase of IK1 density (Fig 6A), although this would come in to play late in the AP. CaMKII may also acutely modulate other ion channels.14, 26

Because of the multiple currents during the AP, computational modeling can help identify the relative contributions of various CaMKII-sensitive currents. We made use of our rabbit ventricular AP model27 and a mouse ventricular AP model28 with some modifications to include CaMKII-dependent alterations on ICa and INa13, 14, 18 and the novel Ito and IK1 data (see online supplement). Figure 7A (insets) shows the calculated APs and Suppl. Table 2 shows the predicted APD60 and 80. Over the full range of stimulation frequencies explored APD60 and 80 are increased in the TG-CaMKIIδC myocytes vs. WT (Suppl. Table 2). In the TG mouse, CaMKII effects on INa and ICa do not significantly impact the APD, whereas reduced Ito,fast and IK1 conspire to prolong the AP. AP prolongation is not reversed at fast rates where TG-CaMKIIδC Ito recovery is faster.

Using our rabbit ventricular myocyte computer model, we showed that the increased rate of Ito recovery and enhancement of Ito,slow are essential for the observed APD shortening27. In the present study the data on IK1 was added to the model, but the resulting change was minimal. Therefore, CaMKII-dependent enhancement of Ito recovery from inactivation and Ito,slow amplitude appear to be the main determinant of AP duration changes in the rabbit myocytes.

Discussion

The present study shows that CaMKIIδC expression in ventricular myocytes induces alterations in both functional expression levels of Ito,fast, Ito,slow, and IK1, as well as acute alterations in the gating of Ito and IK1. Only the latter effects are reversed by inclusion of CaMKII inhibitors. CaMKIIδC reduces expression of Ito,fast (Kv4.2/4.3) and IK1 (Kir2.1), but increases expression of Ito,slow (Kv1.4). CaMKIIδC activity accelerates the recovery of Ito,fast and Ito,slow from inactivation and activates IK1. There are quantitative differences in these effects in the TG mouse model vs. the rabbit overexpression model and these changes can have complex effects on the AP (prolonging the mouse APD, shortening the rabbit APD). Since CaMKII expression levels are enhanced in HF,10, 11 these effects may predispose to ventricular arrhythmias.

Separation of Ito components and acute vs. long-term CaMKII effects

To separate Ito,fast and Ito,slow components of Ito we used the differences in time constants of recovery from inactivation ~10–30-fold)29 and time constants of inactivation (5–10-fold).3 While KV1.4 and KV4.2/4.3 might inactivate and recover in a multi-exponential fashion,30 both methods gave very similar results and the pedestal component was unchanged. This gives us confidence in the component assignments. This is further supported by the Kv1.4 and Kv4.2/4.3 expression data, which largely parallel the CaMKIIδC-induced changes in Ito,slow and Ito,fast amplitudes, respectively.

To distinguish between acute dynamic CaMKII-dependent regulation of Ito and longer term effects due to altered protein expression, we used the selective CaMKII inhibitor AIP. Effects that were reversed by AIP were deemed acute (potentially mediated by CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of channel subunits), whereas CaMKII effects that were not prevented by AIP were assumed to be longer term alterations (e.g. in protein expression). These are functional distinctions, and complementary work is needed to define which specific CaMKII target sites are responsible for acute gating changes and longer term effects.

CaMKII regulates Ito functional expression

The CaMKIIδC-induced changes in amplitudes of Ito,fast and Ito,slow were insensitive to AIP. This was true for mouse and rabbit myocytes and for both methods of separating Ito components, and also for the slowing of Ito,slow inactivation in the mouse. CaMKIIδC overexpression enhanced Ito,slow amplitude and Kv1.4 expression in the TG CaMKIIδC mouse and after CaMKIIδC overexpression in rabbit myocytes (Table 2). This suggests that the up-regulation of Kv1.4 and Ito,slow is a relatively rapid consequence of CaMKIIδC overexpression. While Kv1.4 protein expression was significantly enhanced, Kv1.4 mRNA changes were less significant. This raises the possibility that CaMKII might enhance trafficking and/or stability of Kv1.4 in the sarcolemma.

Table 2.

Effects of CaMKIIδC overexpression on K-currents

| Ito,fast | Ito,slow | IK1* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit | |||

| amplitude (from recov.) | Ø | ↑ | |

| amplitude (from inact.) | Ø | ↑ | |

| amplitude (peak) | ↓ | ||

| Protein | =Kv4.3 | ↑Kv1.4 | |

| mRNA | =Kv4.2/3 | =Kv1.4 | ↓Kir2.1 |

|

| |||

| Mouse | |||

| amplitude (from recov.) | ↓ | ↑ | |

| amplitude (from inact.) | ↓ | ↑ | |

| amplitude (peak) | ↓ | ||

| Protein | ↓Kv4.2/3 | ↑Kv1.4 | |

| mRNA | ↓Kv4.2/3 | ↑Kv1.4 | ↓Kir2.1 |

|

| |||

| Both | |||

| Ito amplitudes unaltered by AIP | |||

| Ito inactivation kinetics unaltered | |||

| Ito,fast and Ito,slow recover faster from inactivation (acutely AIP-sensitive) | |||

Legend: Maximal currents, protein data, and mRNA levels were derived from I–V-curves, Western blots, and RT-PCR results, respectively. ↑=upregulation; ↓=downregulation; Ø=unaltered.

with AIP, which reduces IK1 in all cases

Ito,fast density and KV4.2 mRNA and protein were reduced in CaMKIIδC TG mice, but not during short-term CaMKIIδC overexpression in rabbit. There are several possible reasons: 1) the CaMKIIδC-dependent downregulation of Ito,fast takes longer than 24 h to develop, 2) Ito,fast functional downregulation depends on hypertrophy and/or HF-dependent pathways caused by CaMKIIδC overexpression, 3) rabbit and mouse regulate functional Ito,fast differentially. Ito and KV4.2/4.3 downregulation are typical in many models of hypertrophy or HF,6, 22–24 and the fetal KV1.4 subunit increases during hypertrophy23 and in HF,24 where CaMKII activity is increased.10, 11 A remaining question is how CaMKII mediates the altered expression of channel proteins responsible for Ito.

One potential pathway by which CaMKII may regulate transcription of transient outward K-channels involves phosphorylation of type II histone deacetylases.31, 32 Indeed, this system is more activated in rabbit and human HF where CaMKII is upregulated.9–11, 33

The extent of Kv4.2 downregulation in CaMKIIδC mice (~20%) was less than the reduction of Ito,fast (~50%). KChIP2 is expressed in heart, and when it is co-expressed with KV4.2 (but not with KV1.4), it increases Ito amplitude, slows inactivation and enhances recovery from inactivation.34 Here KChIP2 gene expression was reduced (by ~50%) in CaMKIIδC-TG mice. Thus, the Ito,fast density reduction may be due to both decreases in Kv4.2 and KChIP2. Notably, chronic CaMKII inhibition in mouse was reported to downregulate KChIP2,15 implying that CaMKII increases KChIP2 expression, which we do see in the rabbit experiments (Suppl Fig 1B). It is possible that the KChIP2 downregulation in TG CaMKIIδC-overexpression is secondary to the development of hypertrophic/HF signaling. This may also help explain why acute CaMKIIδC overexpression in rabbit failed to reduce Ito,fast.

CaMKII acutely alters Ito gating

The lack of AIP effects on Ito amplitude indicates that CaMKII does not exert acute regulation on Ito amplitude or Em-dependence of activation. However, we found that CaMKII prominently accelerates Ito,fast and Ito,slow recovery from inactivation. This suggests that CaMKII acts directly on Ito.

In HEK293 cells CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of Ser123 of KV1.4 channels modulates the inactivation of Ito,slow leading to an accelerated recovery from inactivation.35 Our study suggests that CaMKII enhances Ito,slow recovery also in rabbit and mouse myocytes.

Initial evidence for a CaMKII-dependent regulation of Ito,fast came from human atrial myocytes showing that CaMKII inhibition accelerated Ito,fast inactivation.36 Similar results were obtained from rat ventricular myocytes37 and in heterologeous expression of KV4.2/KV4.3.37, 38 It was suggested that CaMKII acts on KV4.3 by a direct effect at Ser550, thereby prolonging open-state inactivation and accelerating the rate of recovery from inactivation.38 At least in vitro, CaMKII phosphorylation sites at Ser438 and Ser459 of KV4.2 have been identified.39 Therefore, the CaMKII-dependent effect on Ito,fast recovery observed here may be mediated via phosphorylation of one or more of those sites.

CaMKII regulates functional expression and regulation of IK1

We show that the AIP-insensitive IK1 and Kir2.1 expression, were significantly downregulated in CaMKIIδC-TG mice and rabbit myocyte upon short-term CaMKIIδC overexpression (by 30–40%). So, CaMKIIδC reduces functional expression of IK1. This may partly explain the downregulation of IK1 in HF, where IK1 is down-regulated ~40–50%,2, 22 and may be a consequence of chronically enhanced CaMKII activity in HF.

Acute modulation of IK1 by CaMKII seems more complex. In all cases, acute CaMKII inhibition reduces IK1 density, suggesting a constitutive CaMKII-dependent activating effect on IK1 amplitude. The overall effect of CaMKIIδC overexpression was to increase IK1 in rabbits, but to decrease IK1 in the TG mouse. We infer that in the rabbit the acute activating effect of CaMKII on IK1 exceeds the moderate decrease in expression induced by CaMKIIδC overnight. In the TG mice, the reduction in IK1 expression may predominate over the acute activating effect of CaMKII, explaining the overall reduced IK1.

Heterologous Kir2.X channels are regulated by PKA, PKC and tyrosine kinases and some phosphorylation sites in the C-terminal of Kir2.1 and Kir2.3 have been confirmed biochemically.40 Therefore, it is possible that CaMKII may alter IK1 through direct channel phosphorylation.

Cell hypertrophy

Myocyte hypertrophy seen in CaMKIIδC-TG mice13 could dilute K-channel current density even if no changes in channel transcription per cell occurred. There was no change in rabbit ventricular myocyte membrane capacitance during the 24 h of exposure to adenovirus (Suppl. Fig. 2), ruling out this complication. For the mouse, the cellular hypertrophy (Suppl. Fig 2) would modestly decrease (<25%) K-current density (if expression/cell is unaltered). Since Ito,fast density was reduced by ~50% and Ito,slow density was increased in the CaMKIIδC TG mice, this does not influence our conclusions.

Influence of altered K-currents on APD

CaMKIIδC overexpression prolonged APD in mouse, but shortened APD in rabbit. This disparity may depend on differences in CaMKII-induced changes and species differences in the ionic currents. The mouse APD is short and Ito critically determines APD.5, 41 CaMKIIδC overexpression in mouse myocytes decreased total Ito (Fig 1A), attributed to a large decrease of Ito,fast. At physiological heart rates in mouse Ito,slow will have less impact than implied by Fig 1. The net reduction in Ito may explain the prolonged APD in TG mice, although reduced IK1 (Fig 6A) could also contribute. CaMKII overexpression increases INa and ICa in mice18 which would also prolong APD, so distinguishing the relative contributions may require computer modeling.

Ito can influence APD in the rabbit myocyte, but its influence on APD is weaker than for mouse. In rabbit myocytes overall Ito was slightly (Fig 2A), due to an acute up-regulation of Ito,slow (Fig 2C). This would shorten APD, and for the rabbit Ito,slow is more likely to be relevant. In addition, the accelerated recovery from inactivation would enhance Ito,slow availability. This would shorten APD, as observed. The increased IK1 could also contribute to APD shortening, while the increases in INa and ICa14, 18 would prolong APD.

Computational modeling

To delineate the relative contributions of Ito and IK1 to the APD we used computational modeling. We incorporated the measured CaMKII-dependent alterations on ICa, INa, Ito and IK1 in a mouse myocyte model28, 42 (see supplemental data) similar to our previous study.27 Equations for the fast and slow component of Ito and a Markovian formulation of INa27,43 were introduced.44 In TG CaMKIIδC mouse myocytes, the reduced Ito,fast is the dominant cause of the observed AP prolongation. While the greater ICa and INa did not significantly alter APD, the decreased IK1 in the CaMKIIδC mouse slightly slows the terminal repolarization making a slight contribution to the APD increase.

For rabbit, we used our previously published model incorporating CaMKII-dependent alterations on ICa, INa and Ito.27 The increased rates of Ito recovery and Ito,slow amplitude are essential for APD shortening, whereas the changes in INa and ICa gating alone tend to prolong the AP duration.27 The addition of the increased IK1 density caused only a few milliseconds further reduction in APD. The fact that AIP reversed the effects of CaMKIIδC on APD in rabbit myocytes indicates that the accelerated Ito recovery is the main determinant of the APD changes. The effect of CaMKII could potentially serve as a Ca-dependent physiologic feedback mechanism. That is, increased [Ca]i (via CaMKII) could enhance Ito recovery, resulting in APD shortening and reduced Ca influx and [Ca]i.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joan Heller Brown, UCSD for kindly providing the TG mice.

Funding Sources

Dr. Wagner was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Georg-August-University Göttingen. Dr. Bers is supported by NIH grants (HL80101, HL30077). Dr. Maier is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MA1982/2-1, MA1982/4-1), Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kardiologie, and Drs. Bers and Maier by the Fondation Leducq.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Gwathmey JK, Copelas L, MacKinnon R, Schoen FJ, Feldman MD, Grossman W, Morgan JP. Abnormal intracellular calcium handling in myocardium from patients with end-stage heart failure. Circ Res. 1987;61:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmajothi M, Campbell D, Rasmusson R, Morales M, Trimmer J, Nerbonne J, Strauss H. Distinct transient outward potassium current (I-to) phenotypes and distribution of fast-inactivating potassium channel alpha subunits in ferret left ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:581–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comer MB, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Lamson DR, Morales MJ, Zhang Y, Strauss HC. Cloning and characterization of an Ito-like potassium channel from ferret ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1383–1395. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:661–678. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kääb S, Dixon J, Duc J, Ashen D, Näbauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, Steinbeck G, McKinnon D, Tomaselli GF. Molecular basis of transient outward potassium current downregulation in human heart failure: a decrease in Kv4.3 mRNA correlates with a reduction in current density. Circulation. 1998;98:1383–1393. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.14.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomita F, Bassett AL, Myerburg RJ, Kimura S. Diminished transient outward currents in rat hypertrophied ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1994;75:296–303. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kääb S, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, O’Rourke B, Pak PH, Kass DA, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res. 1996;78:262–273. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97:1314–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirchhefer U, Schmitz W, Scholz H, Neumann J. Activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:254–261. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch B, Meyer R, Hetzer R, Krause EG, Karczewski P. Identification and expression of delta-isoforms of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ Res. 1999;84:713–721. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier LS, Bers DM. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maier LS, Zhang T, Chen L, DeSantiago J, Brown JH, Bers DM. Transgenic CaMKIIdeltaC overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ Res. 2003;92:904–911. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069685.20258.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack E, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Maier S, Zhang T, Hasenfuss G, Brown J, Bers D, Maier L. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3127–3138. doi: 10.1172/JCI26620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Marionneau C, Zhang R, Shah V, Hell JW, Nerbonne JM, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition shortens action potential duration by upregulation of K+ currents. Circ Res. 2006;99:1092–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249369.71709.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Jr, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang T, Maier LS, Dalton ND, Miyamoto S, Ross J, Jr, Bers DM, Brown JH. The δC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;92:912–919. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069686.31472.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohlhaas M, Zhang T, Seidler T, Zibrova D, Dybkova N, Steen A, Wagner S, Chen L, Brown J, Bers D, Maier L. Increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak but unaltered contractility by acute CaMKII overexpression in isolated rabbit cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;98:235–244. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200739.90811.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner S, Seidler T, Picht E, Maier L, Kazanski V, Teucher N, Schillinger W, Pieske B, Isenberg G, Hasenfuss G, Kögler H. Na+-Ca2+ exchanger overexpression predisposes to reactive oxygen species-induced injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu WZ, Wang SQ, Chakir K, Yang D, Zhang T, Brown JH, Devic E, Kobilka BK, Cheng H, Xiao RP. Linkage of beta1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:617–625. doi: 10.1172/JCI16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel S, Campbell D, Morales M, Strauss H. Heterogeneous expression of KChIP2 isoforms in the ferret heart. J Physiol. 2002;539:649–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.015156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beuckelmann DJ, Näbauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circ Res. 1993;73:379–385. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodi I, Muth JN, Hahn HS, Petrashevskaya NN, Rubio M, Koch SE, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Electrical remodeling in hearts from a calcium-dependent mouse model of hypertrophy and failure: complex nature of K+ current changes and action potential duration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1611–1622. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akar F, Wu R, Juang G, Tian Y, Burysek M, DiSilvestre D, Xiong W, Armoundas A, Tomaselli G. Molecular mechanisms underlying K+ current downregulation in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2887–H2896. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00320.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Näbauer M, Kääb S. Potassium channel down-regulation in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:324–334. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan W, Bers DM. Ca-dependent facilitation of cardiac Ca current is due to Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H982–993. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandi E, Puglisi J, Wagner S, Maier L, Severi S, Bers D. Simulation of Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on rabbit ventricular myocyte ion currents and action potentials. Biophys J. 2007;93:3835–3847. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demir S. Computational modeling of cardiac ventricular action potentials in rat and mouse: Review. Jpn J Physiol. 2004;54:523–530. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.54.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Bett G, Jiang X, Bondarenko V, Morales M, Rasmusson R. Regulation of N- and C-type inactivation of Kv1.4 by pH(o) and K+: evidence for transmembrane communication. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H71–H80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00392.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Bondarenko V, Qu Y, Bett G, Morales M, Rasmusson R, Strauss H. Time- and voltage-dependent components of Kv4.3 inactivation. Biophys J. 2005;89:3026–3041. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson EN, Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Zhang T, Bossuyt J, Li X, McKinsey TA, Dedman JR, Olson EN, Chen J, Brown JH, Bers DM. Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:675–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI27374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossuyt J, Helmstadter K, Wu X, Clements-Jewery H, Haworth RS, Avkiran M, Martin JL, Pogwizd SM, Bers DM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIδ and protein kinase D overexpression reinforce the histone deacetylase 5 redistribution in heart failure. Circ Res. 2008;102:695–702. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling HP, Mendoza G, Hinson JW, Mattsson KI, Strassle BW, Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roeper J, Lorra C, Pongs O. Frequency-dependent inactivation of mammalian A-type K+ channel KV1.4 regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3379–3391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tessier S, Karczewski P, Krause EG, Pansard Y, Acar C, Lang-Lazdunski M, Mercadier JJ, Hatem SN. Regulation of the transient outward K+ current by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases II in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 1999;85:810–819. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colinas O, Gallego M, Setien R, Lopez-Lopez JR, Perez-Garcia MT, Casis O. Differential modulation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channels by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1978–1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01373.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sergeant GP, Ohya S, Reihill JA, Perrino BA, Amberg GC, Imaizumi Y, Horowitz B, Sanders KM, Koh SD. Regulation of Kv4.3 currents by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C304–313. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00293.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Schrader LA, Wu GY, Gatchel JR, Johnston D, Sweatt JD. Calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II modulates Kv4.2 channel expression and upregulates neuronal A-type potassium currents. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3643–3654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0154-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruppersberg JP. Intracellular regulation of inward rectifier K+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 2000;441:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s004240000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo W, Li H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Functional consequences of elimination of Ito,f and Ito,s: early afterdepolarizations, atrioventricular block, and ventricular arrhythmias in mice lacking Kv1.4 and expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 α subunit. Circ Res. 2000;87:73–79. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandit S, Giles W, Demir S. A mathematical model of the electrophysiological alterations in rat ventricular myocytes in type-I diabetes. Biophys J. 2003;84:832–841. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74902-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clancy C, Rudy Y. Na+ channel mutation that causes both Brugada and long-QT syndrome phenotypes - A simulation study of mechanism. Circulation. 2002;105:1208–1213. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bondarenko V, Szigeti G, Bett G, Kim S, Rasmusson R. Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1378–H1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.