Abstract

Objective To report acceptability, feasibility, and outcome data from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of a brief intervention for caregivers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Method Eighty-one families were randomly assigned following collection of baseline data to Intervention or Treatment as Usual (TAU). Recruitment and retention rates and progression through the protocol were tracked. Measures of state anxiety and posttraumatic stress symptoms served as outcomes. Results Difficulties enrolling participants included a high percentage of newly diagnosed families failing to meet inclusion criteria (40%) and an unexpectedly low participation rate (23%). However, movement through the protocol was generally completed in a timely manner and those completing the intervention provided positive feedback. Outcome data showed no significant differences between the arms of the RCT. Conclusions There are many challenges inherent in conducting a RCT shortly after cancer diagnosis. Consideration of alternative research designs and optimal timing for interventions are essential next steps.

Keywords: anxiety, caregivers, intervention, parents, pediatric cancer, posttraumatic stress, randomized clinical trial

Recognizing that a diagnosis of childhood cancer causes distress, national organizations recommend that psychosocial services be provided to families at diagnosis (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997; Noll & Kazak, 2004). Unfortunately, there are few published studies on interventions around the time of diagnosis and recognition that the psychosocial needs of families are inadequately addressed (Institute of Medicine, 2007). In this article we briefly discuss the nature of parental distress at diagnosis and the evidence regarding psychosocial interventions for families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. We then focus on the acceptability, feasibility, and outcomes from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program for Newly Diagnosed Families (SCCIP-ND), a program adapted from an intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families (SCCIP; Kazak et al., 1999; Kazak, Alderfer, Streisand et al., 2004).

There is substantial evidence for parental (particularly maternal) distress around the time a child is diagnosed with cancer, across psychological outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress (Barrerra et al., 2004; Brown, Madan-Swain, & Lambert, 2003; Dahlquist, Czyzewski, & Jones, 1996; Dolgin et al., 2007; Frank, Brown, Blount, & Bunke, 2001; Kazak et al., 1997; Kazak, Alderfer, Rourke et al., 2004; Manne, Miller, Meyers, Wolner, & Steinherz, 1996; Sloper, 2000; Steele, Dreyer, & Phipps, 2004). Rates of traumatic stress are noteworthy. For example, 51% of mothers and 40% of fathers within 2 weeks of their child's cancer diagnosis met DSM-IV criteria for Acute Stress Disorder (Patiño-Fernández et al., 2008). Approximately 68% of mothers and 57% of fathers of children in treatment for at least 2 months reported posttraumatic stress symptoms in the moderate to severe range (Kazak, Boeving, Alderfer, Hwang, & Reilly, 2005).

Prospective reports indicate that distress is heightened for mothers and fathers during the first few months of treatment and diminishes over a year (Dahlquist et al., 1996; Sawyer, Antoniou, Toogood, & Rice, 1997; Sawyer, Antoniou, Toogood, Rice, & Baghurst, 2000). An important subset of these families, however, experience persisting and/or escalating distress with higher levels of distress during treatment predicting ongoing difficulties (Best, Streisand, Catania, & Kazak, 2002; Dolgin et al., 2007; Kazak & Barakat, 1997; Kupst & Schulman, 1988; Kupst et al., 1995; Sawyer, Antoniou, Toogood, Rice, & Baghurst, 1993; Steele, Long, Reddy, Luhr, & Phipps, 2003). These findings support identifying this more vulnerable group of families and intervening early.

The strongest evidence for intervention during treatment is a maternal problem-solving protocol tested in a multi-site trial of 430 mothers (Sahler et al., 2005). Mothers receiving the intervention had significantly higher scores on measures of problem solving and lower scores on measures of negative affect immediately after the intervention, with positive effects maintained for depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms 3 months post intervention. Other intervention studies have been more modest pilot studies, such as stress reduction for mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation (Streisand, Rodrique, Houck, Graham-Pole, & Berlant, 2000). Mothers who completed that intervention reported that they used significantly more stress reduction techniques than the control group, however there were no differences in levels of stress between the groups. General family psycho-educational approaches have also not, to date, demonstrated differences in wellbeing over no-treatment conditions (Hoekstra-Weebers, Heuvel, Jaspers, Kamps, & Klip, 1998).

The potential importance of providing an evidence-based intervention relevant for families near the time of cancer diagnosis led us to develop and test an intervention for parents/caregivers. Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program-Newly Diagnosed (SCCIP-ND) is a manualized three-session intervention for parents/caregivers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. This intervention, like our earlier intervention for families of survivors of childhood cancer (SCCIP), integrates cognitive behavioral and family therapy approaches. The focus of SCCIP-ND is explicitly interpersonal in nature, directed at the level of the dyadic relationship between caregivers. The original SCCIP intervention was family-systems based, using a multiple family group format, and was tested in a RCT of 150 families. Treatment families showed reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) across family members (Kazak et al., 1999; Kazak, Alderfer, Streisand et al., 2004).

The goal of SCCIP-ND is to promote healthy family adjustment to pediatric cancer, specifically targeting parental distress to prevent the development of longer-term cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms, and to do so within a brief intervention format. In a pilot study of 19 families (38 caregivers; Kazak, Simms et al., 2005) preliminary support was found for greater reductions in traumatic stress and anxiety for mothers and fathers in the treatment group compared to caregivers in the treatment as usual condition. Consent was obtained quickly after diagnosis (median 0 days) and enrolled parents reported that the intervention was highly acceptable. Although the participation rate was low (40%), retention was good (79%). The data were promising and supportive of initiating a larger RCT, particularly with attention to improving the participation rate.

Having now completed the RCT, we have identified challenges associated with conducting this research during the acutely stressful period around a child's cancer diagnosis.Therefore, the purpose of this article is to present data on acceptability (recruitment, retention, participant report) and feasibility (study flow, implementation) using definitions of these terms consistent with that used in other samples of families of children with ADHD (Bennett et al., 1996) and headache (Cottrell, Drew, Gibson, Holroyd, & O’Donnell, 2007). We also present outcomes (anxiety, traumatic stress) from the RCT. The larger goal of the article is to provide empirical data about the challenges associated with intervention research during the early phases of treatment for childhood cancer that can inform further work in this area.

Method

Overview of Study Design

After providing informed consent per IRB-approved procedures for the RCT, participants (parents/caregivers) completed Time 1 (T1) data collection and were subsequently randomized (as families) to SCCIP-ND or standard psychosocial care/treatment as usual (TAU). Time 2 (T2) data was collected 1 month following the third and final session for families in SCCIP-ND and within a comparable time period for the TAU group. Primary outcomes were parental state anxiety and symptoms of traumatic stress.

Participants

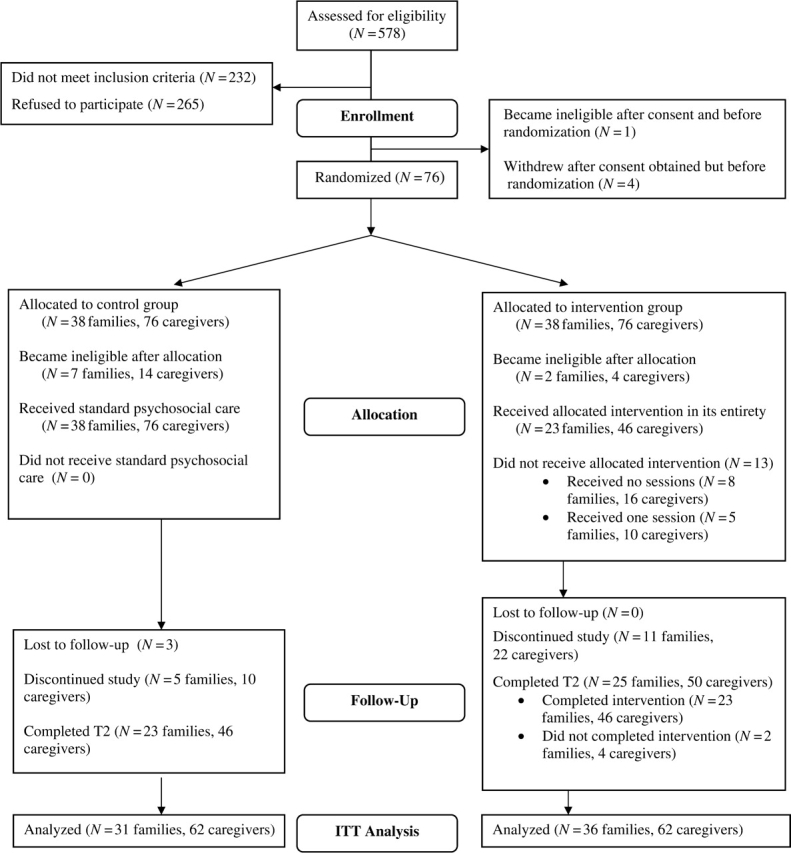

Eighty-one families (162 caregivers) of newly diagnosed patients enrolled in this IRB approved study. Five families withdrew from the study prior to randomization or did not complete their T1 data collection resulting in a sample of 76 families. Thirty-eight families were randomized to the SCCIP-ND group and 38 to the TAU group (Figure 1). Eligible families were English-speaking and had a child between birth and 17 years of age who was receiving chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment at our hospital, had no medical co-morbidities or developmental delay, and was not referred to palliative care. Families needed to have two parents/caregivers to participate and children needed to have been diagnosed within 2 months prior to recruitment. Patients with nonmalignant tumors (e.g., craniopharyngioma) were eligible when the treatment was consistent with that for cancer (i.e., included chemotherapy or radiation).

Figure 1.

SCCIP-ND Flowchart.

Procedure

We accrued families for 3 years (January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2006). Patients new to the oncology service were identified as potentially eligible via daily inpatient Oncology rounds, contact with the outpatient charge nurse, and the daily admission roster. Families were introduced to the study in person by a research assistant as soon as possible after the family meeting, during which they learned of their child's cancer diagnosis and began discussion of the treatment plan options. Because of the interpersonal focus of the intervention and its evolution from a multiple family group model, participation in the study necessitated two caregivers (adults who were directly involved in parenting and childcare activities, including parents, significant others of parents, grandparents, siblings if age 18 years or older, or other extended family). Having a child newly diagnosed with cancer can be particularly stressful and the logistics of caring for the child, as well as attending to other family responsibilities, is challenging for the entire family. It was felt that including two caregivers in the intervention provided families with a unique opportunity to increase communication and support at this time. Primary caregivers were those identified by the family as responsible for the larger amount of direct care for the child. All but one of the primary caregivers were mothers (one father). The secondary caregivers, identified by the primary caregiver as another adult involved directly with care of the child with cancer, were more diverse and included 68 fathers (including three stepfathers and one mother's boyfriend), nine grandmothers, one aunt, one uncle, and two adult siblings (including one stepsibling).

In addition to completing self-report questionnaires and accepting randomization to SCCIP-ND or TAU, participants were also asked to consent to providing 20 cc of blood at each data collection, related to a secondary aim of this study, examining neuroimmune markers in parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer (Lutz Stehl et al., 2008). Consenting to this part of the study was optional and did not affect participation in the primary study. All data collection took place at the hospital at a time and location of convenience for the family and was conducted by research assistants. Randomization was completed by a predetermined concealed random assignment list maintained by a staff member unaware of patient identity. Families were notified of treatment condition in person (if the child was hospitalized) or by telephone. At the time of notification families randomized to SCCIP-ND scheduled their first intervention session. Families who declined participation were asked to provide their reason(s) for doing so.

SCCIP-ND: Procedure for the Intervention Group

Families randomized to the intervention participated in three 45 minute sessions and three booster sessions. The treatment sessions, ideally conducted within 4–6 weeks after diagnosis, focus on identifying the caregivers’ beliefs about the adversities associated with cancer and reframing these beliefs to alter unwanted consequences (e.g., distress, relationship difficulties). The sessions also consider the future role of cancer in the family, with an emphasis on family growth, framed interpersonally and with the goal of promoting communication and mutual support among caregivers (Table I). SCCIP-ND uses a Multiple Family Video Discussion Group (MFVDG), a CD/ROM-based adaptation of Multiple Family Discussion Groups (MFDGs; Steinglass, 1998). This virtual discussion group was developed to provide participants with the opportunity to observe other parents of children with cancer discussing their experiences and responses to diagnosis. Consistent with trauma focused therapies, the MFDG provides controlled exposure to cancer-related potentially traumatic events. Three five-minute video clips are used in the intervention (one in each session linked to the content of that session). The booster sessions, delivered at 1, 2, and 3 months after Session 3, were designed to facilitate families’ continued exposure to the tools and concepts of the intervention. They consisted of printed materials and a CD/ROM mailed to the families’ homes and a phone call conducted by the family's interventionist.

Table I.

SCCIP-ND: Key Constructs and Outline of Intervention

| Four key constructs |

|

| Session 1. Identifying beliefs about cancer, its treatment and the impact on the family | The therapist joins with the caregivers to establish a collaborative relationship and reinforces the importance of the caregivers’ participation (i.e., potential benefits of the study). A cognitive behavioral framework, the A-B-C Model (Ellis, 2001), is introduced for examining the relationship between adversities (diagnosis of pediatric cancer) and beliefs, and between beliefs and the emotional, behavioral and relational consequences for each person and the pair. |

| Session 2. Changing beliefs to enhance family functioning | This session addresses changing one's thoughts to produce different consequences for the family. The therapist continues to join with the family and reaffirm the link between beliefs and relational consequences. For example, caregivers expand their discussion of the impact of cancer and their beliefs on familial and social relationships. Caregivers learn how to use reframing to modify beliefs and their emotional, behavioral and interpersonal consequences. |

| Session 3. Family growth and the future | By focusing on family growth in this session, the therapist helps caregivers consider the future, with cancer occupying an ever-present but diminishing role. The therapist uses two metaphors, “The Family Survival Roadmap” and “Putting Cancer in its Place,” to help caregivers recognize their beliefs about the family's future, and share these beliefs with each other. Finally, the therapist encourages caregivers to consider how they will incorporate what they have learned into their family life. |

| Three monthly boosters | Booster 1 materials were handouts illustrating key concepts in the intervention (e.g., ABC Model, reframing) with suggestions for practice. The second booster consisted of a video discussion among three SCCIP-ND interventionists talking about the key constructs in the intervention and how they might be used by families presented on CD/ROM. The final booster was a phone call from the family's interventionist. This call, intended to provide personal contact and closure with the treatment, focused on follow up as to the family's progress and continued use of the SCCIP-ND approach. |

Four psychology fellows, a psychology intern, a masters-level psychologist, and a doctoral-level nurse were interventionists. Each completed 18 hours of didactic and experiential training led by senior psychologists in the Division of Oncology. Weekly supervision was provided throughout the course of the study and all SCCIP-ND sessions were audio taped. Details of the intervention are described in another paper (Kazak, Simms et al., 2005) and in the treatment manual (available from the corresponding author).

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment fidelity ratings assessing interventionist adherence and competence were provided by an independent team at another institution using a manual developed in collaboration with the SCCIP-ND team. Ratings for adherence and competence were completed separately, using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with descriptive anchors at the lowest point (1), suggesting that the therapist did not engage in behaviors consistent with the manual or was not competent in his/her interaction to the highest point (5), suggesting a high level of adherence or competency. Adherence was operationally defined as the percentage of ratings across all sessions that were rated a 3 or above. The adherence rating was 96% and mean competence scores were 4.22 (Session 1), 3.85 (Session 2), and 4.18 (Session 3).

Standard Psychosocial Care: Procedure for the TAU group

Routine psychosocial care was provided to all newly diagnosed families, irrespective of group assignment. All families in our study (and in the Division of Oncology) were assigned a social worker who attended the initial family meeting, provided resources and supplemental information about diagnosis and treatment, and offered support. Social workers consulted with parents and the medical team on an ongoing basis to facilitate families’ adjustment. The services of child life specialists, including medical play and education, art and music therapies, and assistance with procedures were also provided to all families. Psychologists were available upon referral for child and family behavioral concerns. Families in the TAU group were contacted on three occasions at time intervals similar to those of the booster sessions of SCCIP-ND. In these contacts, families received information on resources for families of children diagnosed with cancer, a card thanking them for their ongoing participation, and a letter informing them of the opportunity to participate in the original SCCIP intervention after completion of SCCIP-ND and cancer treatment.

Measures

Measures Completed by Caregivers

Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS)

The ASDS (Bryant, Moulds & Guthrie, 2000), used at T1, is a 19-item self-report inventory that assesses parental acute stress symptoms in relation to their child's cancer diagnosis. Items are summed and higher scores reflect greater distress. Test-retest reliability across 2–7 days is excellent (r = .94; Bryant et al., 2000). The ASDS Total Score has been used previously as a measure of posttraumatic stress in parents of pediatric patients (Patiño-Fernández, et al., 2008) and demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach's alpha = .90).

Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)

The IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, 1997) is a 22-item self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of re-experiencing, arousal, and avoidance occurring within the past week. It was used at T2 as a measure of PTSS. Internal consistency of the scale for parents within our sample was high (Cronbach's alpha = .93) and adequate test-retest reliability has previously been reported (Baumert et al., 2004; Weiss, 2004; Weiss & Marmar, 1997).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI (Spielberger, 1983) is a self-report questionnaire assessing current/situational (state) and stable/dispositional (trait) anxiety symptoms. The full 40-item STAI was administered at T1 and the 20-item state anxiety portion was administered at T2. Internal consistency within our sample was good for both the state and trait scales (Cronbach's alpha for state = .96 at T1, for trait = .89). Test-retest reliability across an eight-week period in other samples is, as predicted, low for state anxiety (.16–.33) and high for trait anxiety (.76–.86), with high internal consistency and adequate construct and discriminative validity across gender and ethnic groups.

Program Evaluation

After Session 3, caregivers who participated in SCCIP-ND completed an 11-item evaluation assessing satisfaction with the intervention structure, content, and materials. A final open-ended question asked for comments/suggestions about SCCIP-ND and reactions to the MFVDG.

Measures Completed by Oncology Staff

Social Work Activity Form (SWAF) and the Child Life Activity Form (CLAF)

SWAF and CLAF were developed by our team to track contact and services provided to families by social work and child life staff in the first month after diagnosis. The data were used to ascertain psychosocial contacts for all participating families. Social workers and child life therapists reported the time they spent (in half-hour increments, ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 h) with families during each of the first four weeks of the child's cancer experience, engaging in activities involving: supportive counseling, medical care issues, education/school contact, referrals, and for social workers specifically, activities involving community/financial organizations and legal issues.

The Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale (ITR-2)

The ITR-2 (Werba et al., 2007) provides a categorization of the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment from least intensive (Level 1) through most intensive (Level 4). Ratings were based on treatment modality (radiation, chemotherapy, surgery) and stage/risk level for the patient, based on chart data extracted by a pediatric oncologist (ATR), blind to patient identity. Ratings were completed by two independent pediatric oncologists, blind to patient identity. Content validity for the ITR-2 was demonstrated in previous samples by agreement between internal criterion raters and external criterion raters (r = .95). Inter-rater reliability on the current sample was .96.

Data Analyses

Acceptability and Feasibility

To assess acceptability the percentage of eligible families recruited, enrolled and retained is reported. To examine whether intervention participation and retention was related to demographic and disease/treatment variables (child age, child gender, child ethnicity, diagnosis, treatment intensity, parent marital status, parent education, family income), a series of chi-squares for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables were completed comparing families that remained in the study to those that withdrew. ASDS and STAI scores at T1 were compared for caregivers who withdrew and those who remained using independent t-tests. These analyses were conducted for the whole sample and within treatment condition. Binomial tests were used to compare the intervention arms in terms of participation, withdrawal, and retention rates. Fisher's exact tests were used when fewer than five cases were represented in any condition. Additional information was gathered to evaluate the acceptability of the intervention by reviewing caregiver responses to items on the Program Evaluation, including an optional open-ended question. Feasibility, specifically implementation, was evaluated by summarizing the flow through the study (time from diagnosis to consent, consent to T1, completion of the sessions [for the SCCIP-ND group], and completion of T2) using medians and ranges.

Outcome Analyses

The study used an intent-to-treat design. Prior to conducting outcome analyses, a series of t-tests and Chi-square analyses were used to evaluate the equivalency of the SCCIP-ND and TAU groups, including patient and family demographic characteristics, treatment intensity rating, and STAI and ASDS scores at T1. To examine the efficacy of the intervention, the SCCIP-ND and TAU groups were compared on T2 STAI and IES-R data through two analyses. Primary and secondary caregivers’ data were analyzed separately using independent t-tests and a linear mixed effects regression model was applied to T2 data from both primary and secondary caregivers while accounting for the within-family correlation. A multiple imputation procedure was done to estimate data missing at T2. For each imputation, a chain of linear regression equations was used to predict the missing data as a function of caregiver status (i.e., primary or secondary), treatment arm, acute stress at T1, and trait and state anxiety at T1. All descriptive statistics and tests results were summarized based on five imputed datasets according to Rubin's rules (Rubin, 1987). With a total of 76 caregivers from 38 families in each group, we had 80% power to detect moderately sized effects for the between-subject factor (i.e., group assignment) with 5% type I error, for both the t-tests analyzing primary and secondary caregivers separately (effect size = .42) and for the linear mixed effects regression model (effect size = .52) assuming a conservative estimated correlation of .3 between the outcome measures from the same family.

Results

Acceptability and Feasibility

Recruitment

Over the 36 months of enrollment, a large number of potentially eligible patients were identified (N = 578). Of these, 40% (232 families) were ineligible. Most were ineligible due to the diagnosis of a nonmalignant tumor, type of treatment or the other aspects of medical care. Approximately 22% of those identified had a benign tumor or treatment with resection only (N = 106), a co-morbid medical diagnosis (N = 14), or were diagnosed more than 2 months previously (N = 5). Another group of patients were referred to palliative care (N = 9), had a tumor recurrence (N = 4), or died shortly after diagnosis (N = 3). Forty-nine patients received treatment at another hospital. Other reasons for ineligibility included a primary language other than English (N = 23), no secondary caregiver available (N = 13), and developmental delay (N = 6). The enrollment rate for the RCT was 23% (81 of 346 eligible families). The main reasons for not participating, as indicated by the Refusal Questionnaire, included feeling overwhelmed/unwilling to commit the time (35%), primary caregiver not being interested (31%), secondary caregiver not being interested (21%), and having adequate support (10%). Two percent of the sample was lost to follow-up.

Retention

See Figure 1 for patient flow information. During the course of this study, 10 families became ineligible. One of these families became ineligible after signing consent, but prior to randomization. Of the remaining nine families becoming ineligible, all were randomized to condition and seven were assigned to the control group. To preserve randomization, T2 data were estimated for these families as described above.

A total of 22 families dropped out of the study after providing consent. Eighteen of these families did so after randomization (27% of randomized eligible families). Of the 36 families randomized to the intervention and remaining eligible, 11 (31%) withdrew from the study prior to completing T2. Seven families completed no sessions of the intervention and four completed only Session 1. Those discontinuing the study reported feeling overwhelmed, having difficulty scheduling sessions with both caregivers, and losing interest in continuing with participation. As an aside, two families completing T2 data collection, thus considered retained in the study, did not attend all intervention sessions, so 23 (61%) of the 38 families assigned to the intervention completed it as planned. In TAU a total of eight families (26%) dropped out. Three families were unable to be contacted after their initial enrollment and five reported unexpected complications with their child's treatment, scheduling conflicts, and in one family, the death of the patient's sibling. The proportion of families withdrawing from the SCCIP-ND group (n = 11) was not significantly different from that withdrawing from the TAU group (n = 8; p = .60).

There were no differences between study completers and those who withdrew on demographic and disease/treatment characteristics. Seven out of fourteen families (50%; 95% CI: 23–77%) with one or two nonbiological parents as caregivers withdrew from the study, compared to 14 of 53 families with two biological parents (26%: 95% CI: 15–40%), however this difference in distributions was not statistically significant (p = .11). Primary caregivers who remained in the study (M = 48.09, SD = 14.65), compared to those who withdrew (M = 33.40, SD = 1.72) had significantly higher ASDS total scores, t (26) = 4.77, p ≤ .001. Conversely, secondary caregivers who remained had significantly lower scores on trait anxiety at T1 (M = 38.76, SD = 7.37), t (36) = –2.52, p = .016, than those who withdrew (M = 47.80, SD = 8.29). There were no other differences in traumatic stress symptoms or anxiety at T1 between caregivers who completed the intervention versus those who withdrew.

Implementation

SCCIP-ND was designed to be delivered within the first months after diagnosis. In order to do so, the study needed to be presented to the parents/caregivers and consent obtained shortly after diagnosis. Five families provided informed consent within 48 h of diagnosis. The majority took longer; the process of consenting a family generally consisted of multiple contacts extending over several weeks (Median = 15 days post diagnosis, range = 2–45 days). There were three families who consented 3 months after the diagnosis. These families were removed from the analyses computing the median from the first contact to consent, but were retained for all additional analyses. With respect to completing the T1 assessment, the median was 9 days (range = 0–119 days). Families were given the option to schedule interventions when convenient for them, including evening and weekend hours, and childcare was provided; they tended to prefer scheduling around their child's hospital admissions and clinic visits.

Participant Feedback

Participants’ ratings on the Program Evaluation form were very positive (Table II). Families viewed the topics discussed as important and helpful and found the timing and format of the intervention to be acceptable. These responses show support for the acceptability of SCCIP-ND and the MFVDG. In general, comments made by caregivers suggested that the intervention was particularly helpful to them as they coped with the early stages of their child's cancer experience and that the MFVDG was very informative and educational, and helped normalize their thoughts and feelings regarding their current experience. In addition to these general comments one caregiver reported that the MFVDG was “less scary than being in a ‘live’ discussion group,” suggesting an additional benefit of this unique intervention format. Caregivers also provided suggestions for improving the intervention such as including more information regarding the children described in the MFVDG, providing more flexibility with scheduling and incorporating additional web-based tools, and lastly, one caregiver reported that the intervention would have been more helpful if she had been able to participate closer to the time of diagnosis.

Table II.

Acceptability of SCCIP-NDa

| Primary (N = 22) |

Partners (N = 21) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Maybe | No | Yes | Maybe | No | |

| The three-session format worked well | 21 | 1 | 20 | 1 | ||

| The handouts and worksheets were easy to understand | 21 | 1 | 19 | 2 | ||

| The timing of this program was appropriate | 18 | 4 | 19 | 2 | ||

| We learned something new | 21 | 1 | 18 | 3 | ||

| The topics were important | 22 | 20 | 1 | |||

| The program was helpful to us | 21 | 1 | 19 | 2 | ||

| The program was interesting | 22 | 20 | 1 | |||

| The program helped us think differently about how cancer affects our family | 17 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 1 |

| The interventionist was tuned into our needs | 21 | 1 | 20 | 1 | ||

| The program will help other newly diagnosed families | 22 | 17 | 4 | |||

| This program will help us to help our child | 21 | 1 | 18 | 3 | ||

aOf the 23 families who completed three sessions of SCCIP-ND, 21 mother–father pairs completed the Program Evaluation (91%); one additional mother completed the form; data are missing for the others.

Equivalency of Groups

Disease and patient characteristics and family demographic variables for SCCIP-ND and TAU are presented in Table III. In general the groups were equivalent. There were no differences on demographic variables or in treatment intensity, except that more mothers and children in the SCCIP-ND group (mothers N = 4, child N = 4) than in TAU (mothers N = 0, child N = 0) endorsed being of Hispanic descent. Chi-square analyses indicated that there were no significant group differences between SCCIP-ND and TAU on the social work (SWAF) and child life activity (CLAF) measures (SWAF week 1, p = .84; SWAF week 2, p = .32; CLAF week 1, p = .39; CLAF week 2, p = .23; CLAF week 3, p = .69; CLAF week 4, p = .87). There were no significant differences between the groups on treatment intensity (ITR, p = .32).

Table III.

Demographic Characteristics of SCCIP-ND, TAU and Total Sample

| SCCIP-ND (N = 38 families) | TAU (N = 38 families) | Total sample (N = 76 families) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age (Median) | 5 years | 7 years | 6 years | .20 |

| Patient gender | ||||

| F | 21 (55.3%) | 14 (36.8%) | 35 (46.1%) | .11 |

| M | 17 (44.7%) | 24 (63.2%) | 41 (53.9%) | |

| Diagnosis (N) | 38 | 38 | 76 | .73 |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 20 (52.6%) | 22 (57.8%) | 42 (55.3%) | |

| Solid tumors | 11 (29.0%) | 8 (21.1%) | 19 (25.0%) | |

| Brain tumors | 7 (18.4%) | 8 (21.1%) | 15 (19.7%) | |

| Treatment intensity (N) | 38 | 38 | 76 | .39 |

| Least intensive | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (2.6%) | |

| Moderately intensive | 12 (31.6%) | 10 (26.3%) | 22 (29.0%) | |

| Very intensive | 19 (50.0%) | 25 (65.8%) | 44 (57.9%) | |

| Most intensive | 6 (15.8%) | 2 (5.3%) | 8 (10.5%) | |

| Caregiver age (median) | .31 | |||

| Primary | 35 years | 36 years | 36 years | |

| Partner | 38 years | 40 years | 39 years | |

| Family Structure (N) | 38 | 37 | 75 | .44 |

| Married/partnered | 31 (81.6%) | 31 (83.8%) | 62 (82.7%) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 2 (5.2%) | 4 (10.8%) | 6 (8.0%) | |

| Never married | 5 (13.2%) | 2 (5.4%) | 7 (9.3%) | |

| Family income (N) | 37 | 35 | 72 | .77 |

| <$50K | 10 (27.0%) | 7 (20.0%) | 17 (23.6%) | |

| $50–99K | 11 (29.7%) | 12 (34.3%) | 23 (31.9%) | |

| ≥$100K | 16 (43.3%) | 16 (45.7%) | 32 (44.5%) | |

| Primary caregiver | ||||

| Educational level (N) | 38 | 38 | 76 | .54 |

| ≤12th grade | 10 (26.4%) | 7 (18.4%) | 17 (22.4%) | |

| Some college | 10 (26.3%) | 14 (36.8%) | 24 (31.6%) | |

| College/advanced degree | 18 (47.3%) | 17 (44.8%) | 35 (46.0%) | |

| Patient ethnicity (N) | 37 | 38 | 73 | .22 |

| Caucasian | 25 (67.6%) | 32 (84.2%) | 57 (76.0%) | |

| African-American | 3 (8.1%) | 2 (5.3%) | 5 (6.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (10.8%) | 0 | 4 (5.3%) | |

| Asian | 3 (8.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | 6 (8.0%) | |

| Mixed race | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | 3 (4.0%) |

Outcomes

State Anxiety

As expected, no differences were observed between groups in STAI scores at T1 for primary caregivers or secondary caregivers based on independent t-tests (all p's > .90; Table IV). On average, both SCCIP-ND and TAU groups showed a significant decrease (all p's < .05) of state anxiety from T1 to T2 for primary and secondary caregivers. When analyzing primary and secondary caregivers separately, the data indicated no differences in STAI scores at T2 between groups for primary caregivers or secondary caregivers. This result held when analyzing both caregivers’ data together in a linear mixed model analysis (p = .97). The difference between SCCIP-ND and TAU was on average, − .10 points (95% CI: −5.62 to 5.81). The within-family correlation was estimated to be .10.

Table IV.

Outcome Data for STAI, ASDS, and IES-R

| SCCIP-ND |

TAU |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | t(df) | p | |

| Time 1 | ||||||

| STAI | ||||||

| Primary | 38 | 48.45 (13.90) | 38 | 48.24 (14.33) | 0.07 (74) | .95 |

| Secondary | 38 | 48.13 (13.90) | 38 | 47.76 (11.92) | 0.22 (74) | .90 |

| ASDS | ||||||

| Primary | 38 | 49.87 (15.66) | 38 | 46.16 (14.59) | 1.07 (74) | .29 |

| Secondary | 38 | 47.63 (14.08) | 38 | 46.87 (15.25) | 0.23 (74) | .82 |

| Time 2 | ||||||

| STAI | ||||||

| Primary | 38 | 42.05 (15.54) | 38 | 42.35 (15.22) | −0.08 (21)a | .94 |

| Secondary | 38 | 42.90 (16.00) | 38 | 42.42 (14.55) | 0.13 (22)a | .90 |

| IES-R | ||||||

| Primary | 38 | 36.10 (26.63) | 38 | 30.60 (27.14) | 0.95 (34)a | .35 |

| Secondary | 38 | 36.26 (27.68) | 38 | 30.94 (26.20) | 0.90 (30)a | .38 |

adf for the multiple imputation is calculated using the following formula:

m is the number of imputations; U is within-imputation variance; B is between-imputation variance.

Traumatic Stress

Independent t-tests indicated no difference in ASDS scores at T1 between the SCCIP-ND and TAU groups for primary or secondary caregivers (all p's > .30, Table IV). At T2, there were no significant differences observed between groups on the IES-R for primary caregivers or secondary caregivers (all p's > .56). The joint analysis by a linear mixed model also showed a nonsignificant effect (p = .22; the difference between SCCIP-ND and TAU was 5.30 points, 95% CI: −3.34 to 14.17). The within-family correlation was estimated to be .14.

Discussion

Elevated distress has repeatedly been demonstrated shortly after diagnosis for family members of children with cancer and distress during treatment is predictive of long-term adjustment. However, evidence-based interventions for childhood cancer patients and their families during this newly diagnosed period are not generally available. Based on this clinical and scientific need we embarked on a trial of a family-based intervention delivered shortly after diagnosis. The course of the trial was met with substantial challenges which included difficulties with participant recruitment and retention (limitations brought about by RCT design and acuity of child illness) and the dynamic nature of distress at the time of diagnosis. Detailed data regarding the process of conducting this RCT at diagnosis was offered to inform future research efforts related to interventions for families during cancer treatment. Although the results regarding outcomes are discouraging, the findings are entwined with the requirements of a RCT and the feasibility and acceptability of a research trial, making it difficult to comment on the eventual effectiveness of this intervention in practice with newly diagnosed families.

With respect to this trial, some difficulties arose in terms of recruitment and retention. Even in a large children's cancer center, many families did not meet inclusion criteria for the study. Efforts were made to keep the exclusion criteria at a minimum, yet they needed to be somewhat restrictive to allow enough homogeneity in the sample to maintain internal validity. The length of time between the introduction of the study to a family and completed informed consent was lengthy. The final participation rate of 23% is very low and makes it difficult to draw conclusions about generalizability. Although a number of changes were made to recruitment procedures and the study protocol in an attempt to increase participation (medical director involvement in recruitment group information sessions for eligible families, reduction of study measures), rates remained low. Study complexity, other competing research protocols, and the acuity of patient illness likely played a role in recruitment rates. The dropout patterns, which were greater for families in the SCCIP-ND condition compared to those in TAU, could be interpreted as reflecting self selection biases, related to negative reactions to the intervention or difficulties with the additional time commitment associated with the active treatment arm. These families may also have felt that they had received adequate support from the intervention sessions they attended, or from sources within the hospital setting. It is plausible that an intervention model that targeted individuals with high levels of distress, rather than a preventive model, would have yielded higher recruitment and retention rates. For families who were generally functioning well with diagnosis, engaging in an intervention of this nature may not have been a priority. Finding ways to measure and screen for difficulties surrounding diagnosis and treatment, as well as providing tiered intervention that addresses varied levels of caregiver distress would be appropriate (Kazak, 2005).

The design of the intervention required two caregivers. The requirement of two caregivers excluded some families that may have been more isolated, more financially strained, or single parent families with more limited social support. A more in depth analysis of the ways in which health insurance coverage, employment status and other economic factors promote or discourage participation in research trials would be helpful in expanding an ecological appreciation of this period of time. Our initial expectation was that grandparents, extended family or close family friends could (and would) participate in single parent families, however only 41% of these families were able to find another family member who could participate. These data are supportive of the importance of designing interventions that are appropriate and accessible for a variety of family constellations and for exploring ways of maintaining an interpersonal focus while not disadvantaging those families who cannot identify a second caregiver.

Those families who engaged in the intervention found the program helpful and suited to their needs. Caregivers commented on the unique format of the multi-family group video discussion groups and reported that the video-taped discussions of other families talking about the time period following diagnosis were especially helpful in providing support and reassurance. Some caregivers additionally commented that having the discussions videotaped was more comfortable and convenient than participating in person in a group. While feedback was positive, it is important to consider that participants represented a fairly selective group of caregivers. Families retained in the treatment arm had primary caregivers (mothers) with higher levels of acute stress and partners (usually fathers) with lower trait anxiety. More highly distressed mothers may be more likely to stay engaged in the program, particularly when their partner is a generally less anxious individual. This also provides additional evidence to support that caregivers who were distressed were more likely to feel that engagement in an intervention like SCCIP-ND would be worthwhile and ultimately helpful to them and their family.

Although the focus of this report is on the acceptability and feasibility of a RCT at diagnosis, we presented basic analyses of the short-term outcomes, recognizing that they are complicated by the difficulties reported with recruitment and retention. As expected, caregivers reported elevations in distress at diagnosis and these levels dissipated over the course of time, irrespective of study group assignment. Although a similar decline in trauma stress symptoms might be expected, the data suggest more variability in these symptoms and a less clear course of recovery. This may be due to the fact that childhood cancer treatment is not one discrete potentially traumatic event (Kazak, Stuber, Barakat & Meeske, 1996). A significant challenge of interventions at diagnosis is showing changes that are more positive (adaptive) than this normative, and potentially variable, course.

The data highlight the potential importance of the timing for RCTs with this population and the need to consider broader windows of recruitment. Sahler et al. (2005) reported an initial participation rate of 50% when approaching families at diagnosis for maternal problem solving. They changed their recruitment protocol, delaying recruitment to 4–16 weeks after diagnosis, and achieved a 75% rate. The experiences of conducting this RCT shortly after diagnosis suggest that subsequent trials may benefit from a broader window of recruitment.

This study was also conducted in the context of a relatively enriched psychosocial environment. That is, all families received psychosocial care. While social work and child life services were documented, it was difficult to track psychological referrals and subsequent treatment. It is possible that the availability of these services outside of the context of a research study may have mitigated against enrollment in the research study. The study required agreeing to randomization and repeated data collection which maybe seen as too burdensome by families in the process of making major medical decisions. It is not known whether a RCT would be more acceptable in an environment with less extensive psychosocial support. Additionally, outcomes of the RCT were likely impacted by the provision of psychosocial services to both the SCCIP-ND and TAU groups.

A broader consideration for future trials concerns study design and whether and when RCTs are the most appropriate designs for evaluating psychosocial services in pediatric contexts. RCTs have emerged as the gold standard in medicine assuring high levels of internal validity when appropriately implemented with the basic feature being random assignment of participants to conditions, and control over potential confounders. Unfortunately, RCTs cannot be implemented with the same level of control when used to evaluate psychosocial interventions. For example, neither participants nor providers can be blinded to treatment condition and nonspecific factors of treatment (e.g., time, attention) are more difficult to define and equate across intervention and control groups. Furthermore, when attempting to evaluate interventions in specific pediatric populations, it is difficult to assure a large homogeneous sample. All of these limitations erode the internal validity of the RCT in our field.

Indeed, the distinction between efficacy and effectiveness in pediatric psychology, particularly for interventions focused on acutely ill or injured children and their families, differs from other populations. That is, the “laboratories” (for developing and testing) interventions are clinical settings (inpatient unit, emergency department, intensive care unit, outpatient clinic). These families are not seen (broadly speaking) in other settings so there is no translation from a university-based laboratory to the clinic. Case and case series designs are necessary to provide additional data that is not well addressed using a RCT, and no one design can answer all of our research questions. Many patient groups (such as families of children newly diagnosed with cancer) are also small in size relative to groups of children often tested in efficacy trials in mental health, highlighting the importance of multi-site trials. These realities complicate intervention research; they limit the ability to test a “pure” intervention, with a well-defined and homogeneous sample. Of course, those interventions that are efficacious under these circumstances have potentially very high relevance and importance for improving the care and psychosocial outcomes of important groups of patients. At a broader level, there has been relatively little formal discussion of these issues in pediatric psychology, suggesting the importance of drawing on the experiences across trials to formulate strategies to overcome these challenges. Moreover, the literature reflects a growing recognition that other methodologies (case, case series, patient preference designs) also contribute to understanding and improving practice (Laurenceau, Hayes, & Feldman, 2007).

The issue of participant perceived need and acceptability is also of central concern. While families of survivors may say that they want interventions at diagnosis, their perspective is different from that of families during the early phases of treatment. More attention to the stakeholders in terms of what may be helpful to them is important in developing efficacious interventions in pediatric psychology. Participant input, via focus groups, for example, may help refine the context and delivery of interventions and help to reflect direct concerns of caregivers at this time. Designs that utilize web based interventions or other media are important considerations in this field and have the benefit of being more accessible for single parent families or those who are more socially isolated. Adding a child component would also likely be appealing to a broader range of families as would home-based interventions.

Conceptualizing interventions within a broader framework, including time since diagnosis and level of distress may help to engage the families most receptive and able to benefit from different models of intervention (Kazak et al., 2007). This will necessitate development of reliable methods for screening to identify those families. Once identified, early and more intensive clinical services for families at greatest psychosocial risk, paired with other intervention models, ideally those that families could use flexibly, as their emotional states, time and needs allow, may help move the field closer to delivering more effective care.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA088828).

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank our research assistants—Katrin Julia Kaal, Ifigenia Mougianis, Portia Jones, Amy Bollenbacher, Kristen Craig, Jaime Spinell, Justin Hulbert, and Allison Myers. We are also grateful for the assistance of Rowena Conroy, PhD, Janet Deatrick, PhD, Courtney Fleisher, PhD, James Klosky, PhD, and Stephanie Schneider, MS who served as interventionists and to Mary T. Rourke, PhD for her assistance throughout the study. Treatment fidelity was developed in collaboration with Drs Art and Christine Nezu at Drexel University. We also thank Ann Leahey, MD and Leslie Kersun, MD for their assistance with treatment intensity ratings.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for the pediatric cancer center and the role of such centers in diagnosis and treatment. Pediatrics. 1997;99:139–140. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, D’Agostino N, Gibson J, Gilbert T, Weksberg R, Malkin D. Predictors and mediators of psychological adjustment in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:630–641. doi: 10.1002/pon.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert J, Simon H, Gundel H, Schmitt C, Ladwig K. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised: Evaluation of the subscales and correlations to psychophysiological startle response patterns in survivors of a life-threatening cardiac event: An analysis of 129 patients with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82(1):29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Power T, Rostain A, Carr D. Parent acceptability and feasibility of ADHD interventions: Assessment, correlates, and predictive validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21:643–657. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best M, Streisand R, Catania L, Kazak A. Parental distress during pediatric leukemia and parental posttraumatic stress symptoms after treatment ends. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;26:299–307. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Madan-Swain A, Lambert R. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their mothers. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:309–318. doi: 10.1023/A:1024465415620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R, Moulds M, Guthrie R. Acute stress disorder scale: A self-report measure of acute stress disorder. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell C, Drew J, Gibson J, Holroyd K, O’Donnell F. Feasibility assessment of telephone-administered behavioral treatment for adolescent migraine. Headache. 2007;47:1293–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlquist L, Czyzewski D, Jones C. Parents of children with cancer: A longitudinal study of parental distress, coping style, and marital adjustment two and twenty months after diagnosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21:541–554. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgin M, Phipps S, Fairclough D, Sahler OJ, Askins M, Noll R, et al. Trajectories of adjustment in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A natural history investigation. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:771–782. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. New York: Prometheus Books; 2001. Overcoming destructive beliefs, feelings and behaviors: New directions for rational emotive therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Frank N, Brown R, Blount R, Bunke V. Predictors of affective responses of mothers and fathers of children with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:293–304. doi: 10.1002/pon.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra-Weebers J, Heuvel F, Jaspers J, Kamps W, Klip E. Brief report: An intervention program for parents of pediatric cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1998;23:207–214. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Barakat L. Parenting stress and quality of life during treatment for childhood leukemia predicts child and parent adjustment after treatment ends. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1997;22:749–758. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.5.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Barakat L, Meeske K, Christakis D, Meadows A, Casey R, et al. Posttraumatic stress, family functioning, and social support in survivors of childhood leukemia and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:120–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Simms S, Barakat L, Hobbie W, Foley B, Golomb V, et al. Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program (SCCIP): A cognitive-behavioral and family therapy intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Family Process. 1999;38:175–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Stuber ML, Barakat LP, Meeske K. Assessing posttraumatic stress related to medical illness and treatment: The Impact of Traumatic Stress Interview Schedule (ITSIS) Families, Systems, & Health. 1996;14:365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Alderfer M, Rourke M, Simms S, Streisand R, Grossman J. Posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:211–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Alderfer M, Streisand R, Simms S, Rourke M, Barakat L, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:493–504. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. Evidence-based interventions for survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:29–39. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Boeving A, Alderfer M, Hwang WT, Reilly A. Posttraumatic stress symptoms during treatment in parents of children with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:7405–7410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Simms S, Alderfer M, Rourke M, Crump T, McClure K, et al. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of a brief psychological intervention for families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:644–655. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A, Rourke M, Alderfer M, Pai A, Reilly A, Meadows A. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: A blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:1089–1098. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupst MJ, Schulman J. Longterm coping with pediatric leukemia: A six year follow up study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1988;13:7–22. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/13.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupst MJ, Natta M, Richardson C, Schulman J, Lavigne J, Das L. Family coping with pediatric leukemia: Ten years after treatment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1995;20:601–617. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Hayes A, Feldman G. Some methodological and statistical issues in the study of change processes in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz Stehl M, Kazak A, Hwang WT, Pai A, Reilly A, Douglas S. Innate immune markers in mothers and fathers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:102–107. doi: 10.1159/000148192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Miller D, Meyers P, Wolner N, Steinherz P. Depressive symptoms among parents of newly diagnosed children with cancer. Children's Health Care. 1996;25:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Micucci J. New York: Guilford; 1998. The adolescent in family therapy: Breaking the cycle of conflict and control. [Google Scholar]

- Noll R, Kazak A. Psychosocial care. In: Ablin A, editor. Supportive care of children with cancer. 3rd. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press; 2004. pp. 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Patiño-Fernández AM, Pai A, Alderfer M, Hwang WT, Reilly A, Kazak A. Acute stress in parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2008;50:289–292. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJ, Fairclough D, Phipps S, Mulhern R, Dolgin M, Noll R, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M, Baghurst P. A prospective study of the psychological adjustment of parents and families of children with cancer. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1993;29:352–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M. Childhood Cancer: A two-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1736–1743. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M, Baghurst P. Childhood cancer: A 4-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. Journal of Peditric Hematology/Oncology. 2000;22:214–220. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sloper P. Predictors of distress in parents of children with cancer: A prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25:79–91. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele R, Long A, Reddy K, Luhr M, Phipps S. Changes in maternal distress and child-rearing strategies across treatment for childhood cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:447–452. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele R, Dreyer M, Phipps S. Patterns of maternal distress among children with cancer and their association with child emotional and somatic distress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:507–517. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass P. Multiple family discussion groups for patients with chronic medical illness. Families, Systems and Health. 1998;16:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Streisand R, Rodrique J, Houck C, Graham-Pole J, Berlant N. Brief Report: Parents of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation: Documenting stress and piloting a psychological intervention program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25:331–337. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Events Scale – Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D. The Impact of Events Scale – Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. 2nd. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Werba B, Hobbie W, Kazak A, Ittenbach R, Reilly A, Meadows A. Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment protocols: The Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale 2.0 (ITR-2) Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2007;48:673–677. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]