Abstract

Background. Uric acid is heritable and associated with hypertension and insulin resistance. We sought to identify genomic regions influencing serum uric acid in families in which two or more siblings had hypertension.

Methods. Uric acid levels and microsatellite markers were assayed in the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) cohort (1075 whites and 1333 blacks) and the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network (HyperGEN) cohort (1542 whites and 1627 blacks). Genome-wide linkage analyses of uric acid and bivariate linkage analyses of uric acid with an additional surrogate of insulin resistance were completed. Pathway analysis explored gene sets enriched at loci influencing uric acid.

Results. In the GENOA white cohort, loci influencing uric acid were identified on chromosome 8 at 135 cM [multipoint logarithm of odds score (MLS) = 2.4], on chromosome 9 at 113 cM (MLS = 3.7) and on chromosome 16 at 93 cM (MLS = 2.3), but did not replicate in HyperGEN. At these loci, there was evidence of pleiotropy with other surrogates of insulin resistance and genes in the fructose and mannose metabolism pathway were enriched. In the HyperGEN-black cohort, there was some evidence of a locus for uric acid on chromosome 4 at 135 cM (MLS = 2.4) that had modest replication in GENOA (MLS = 1.2).

Conclusions. Several novel loci linked to uric acid were identified but none showed clear replication. Widespread diuretic use, a medication that raises uric acid levels, was an important study limitation. Bivariate linkage analyses and pathway analysis were consistent with genes regulating insulin resistance and fructose metabolism contributing to the heritability of uric acid.

Keywords: genomics, hypertension, insulin resistance, linkage analysis, uric acid

Introduction

Uric acid is the main breakdown product of purine metabolism and is largely renally excreted since humans lack a uricase enzyme. Hyperuricaemia is common, particularly among men in the general community. Uric acid can crystalize at levels >6.7 mg/dL [1]. Gouty arthritis and nephrolithiasis are well-described complications of hyperuricaemia, but the vast majority of hyperuricaemic individuals are asymptomatic. Hyperuricaemia is a strong predictor of hypertension, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease [2–6]. Established risk factors for hyperuricaemia include factors that increase dietary purines (e.g. animal-based proteins) and decrease renal clearance of purines (e.g. diuretics and alcoholic beverages). Uric acid levels are also heritable [7,8], and recent genome-wide linkage analyses have identified quantitative trait loci (QTL) in white and Mexican American families [9–11]. These studies have also found evidence of pleiotropy in as much as some loci influencing uric acid also influence other surrogates of insulin resistance (e.g. obesity and diabetes).

This study sought to compare these previously published studies with results of genome-wide linkage analyses in two biracial study populations: the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) and the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network (HyperGEN), both within the Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP) [12]. Genome-wide linkage analyses of uric acid in these families enriched for hypertension may provide new insight into the genetics of uric acid since hypertension is both common [13] and associated with hyperuricaemia [2]. Hyperuricaemia is also associated with insulin resistance, perhaps via dietary fructose, a common sweetener that raises uric acid levels by depleting hepatic ATP with the conversion to fructose-1-P and the subsequent degradation of AMP to uric acid [14]. By raising uric acid levels, fructose impairs glucose uptake by skeletal muscle and insulin levels rise to compensate [15]. Several recent genome-wide studies have found SLC2A9, a glucose, fructose and urate transporter, to be associated with uric acid levels [16–18]. Hyperuricaemia may also lead to chronic kidney disease by activation of renin–angiotensin systems, glomerular hypertrophy/hypertension, renal hypoperfusion and tubulointerstitial fibrosis [19,20]. Bivariate linkage analyses were performed between uric acid and other surrogates of insulin resistance (obesity, diabetes mellitus or triglycerides) and between uric acid and serum creatinine.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The GENOA cohorts recruited non-Hispanic white and black participants from two centres between 1996 and 2000. In Rochester, MN, the Rochester Epidemiology Project [21] was used to identify non-Hispanic white residents of the Olmsted County general population with a diagnosis of essential hypertension before the age of 60 years. In Jackson, MS, residents with essential hypertension were identified through the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort, a general population sample of 45- to 64-year-old non-Hispanic black residents. Probands with evident secondary hypertension were not recruited at either site (e.g. serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL). The hypertensive proband and all siblings were invited to participate if at least one other sibling had essential hypertension. Between 2000 and 2004, 2721 (79%) of the 3434 original GENOA participants (1239 whites and 1482 blacks) returned for a second clinic visit [22]. Serum uric acid levels were measured in 1238 whites and 1468 blacks. Linkage analyses were based on the pedigree relationships of all GENOA participants and the genome-wide microsatellite markers available in 1075 whites and 1333 blacks with measured uric acid levels.

The HyperGEN cohorts were recruited between 1996 and 1999 from five centres: Framingham, MA; Minneapolis, MN; Salt Lake City, UT; Forsyth County, NC; and Birmingham, AL. The NHLBI Family Heart Study was used to identify hypertensive sibships in Massachusetts, Minnesota, Utah and North Carolina. Additional black participants in North Carolina and Alabama were recruited through a variety of media and community sources. As with GENOA, hypertension was confirmed at the study visit by a systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >90 or treatment with anti-hypertensive medications before age 60 years [12]. Probands with evident secondary hypertension were excluded. In addition to the sibships (n = 2342 individuals), parents and unmedicated offspring of index siblings (n = 665 individuals) and a random sample of the community (mostly spouses, n = 918 individuals) were also recruited. Overall, 3925 individuals (1906 whites and 1926 blacks) participated in the visit. Serum uric acid levels were measured in 1832 whites and 1898 blacks. Linkage analyses were based on the pedigree relationships of all HyperGEN participants and the genome-wide microsatellite markers available in 1542 whites and 1627 blacks with measured uric acid levels.

Measurements

The clinic visit for both the GENOA and HyperGEN cohorts included a blood draw, measurement of height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, smoking history and current medications. Use of anti-gout medications was defined as the use of allopurinol, colchicine or probenecid in the last month. Other medications known to affect uric acid levels were also identified: diuretics, aspirin, warfarin, losartan and fenofibrate. Fasting glucose, creatinine, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol were assayed in serum samples. Hypertension was defined by a blood pressure >140/90 or use of anti-hypertensive medications. Diabetes was defined by a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL or use of oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin. Serum uric acid was measured with a standard automated uricase enzymatic assay [23] at a separate central laboratory for each network. The GENOA cohort used a Hitachi 911 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) analyser and the HyperGEN cohort used a Vitros 700 analyser (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY). A set of 381 microsatellite markers for GENOA and 391 microsatellite markers for HyperGEN across the 22 autosomes were genotyped by the Mammalian Genotyping Center of the Marshfield Medical Research Foundation (Marshfield, WI) using a standard polymerase chain reaction. Data cleaning to verify family relationships and identify sample mix-ups was performed separately at each network as described elsewhere [19,20]. Genotyping errors that could not be resolved were recoded as missing.

Heritability and linkage analyses

Mean levels of uric acid by gender and race were estimated within the GENOA and HyperGEN cohorts using mixed models, where a random sibship effect was included to model the dependence within a family [24]. The genetic analyses were performed separately in GENOA whites, GENOA blacks, HyperGEN whites and HyperGEN blacks. Uric acid levels were transformed using the van der Waerden transformation to meet the assumption of normality for variance component linkage analysis. Analyses were age–sex-adjusted or multivariable-adjusted (age, sex, serum creatinine, body mass index, current smoker, diabetes, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, anti-gout medications, diuretics, aspirin, warfarin, losartan and fenofibrate). Alcohol intake and C-reactive protein were available for GENOA; including these variables in models had no substantive effect on the results and is not shown. Excluding individuals on anti-gout medications also had no substantive effect on the results (data not shown). The heritability estimate was computed as the percent of variance in the quantitative measure of uric acid that is explain by the familial relationship,  , where

, where  is the variance due to shared familial effects and

is the variance due to shared familial effects and  is the residual variance from a polygenic model [25,26], after adjustment for age and sex.

is the residual variance from a polygenic model [25,26], after adjustment for age and sex.

Quantitative linkage analysis using a variance component approach was implemented using the multic R library [25–27]. Identity by descent matrices were computed using Simwalk2 [28,29]. Allele frequencies were estimated based on each study cohort. Test for linkage was based on the likelihood ratio test with LOD scores also calculated. For the genome-wide univariate linkage analyses, a MLS >3.00 (P < 0.0001) was considered statistically significant evidence of linkage and a MLS >2.00 (P < 0.001) was considered suggestive evidence of linkage [30]. The genome-wide linkage results were compared between the GENOA and HyperGEN cohorts to assess replication. Meta-analyses for both whites and blacks were also completed by combining the linkage results in the GENOA and HyperGEN networks using the GSMA (genome search meta analysis) method outlined by Wise et al. with age- and sex-adjusted LOD scores and 30 cM bins [31].

Bivariate linkage can have the advantage of greater statistical power than univariate linkage when a single locus influences multiple traits (i.e. pleiotropy). Pleiotropy of loci influencing uric acid and other surrogates of insulin resistance has been previously reported [9–11]. For this study, bivariate linkage analyses were performed between uric acid and each of the following measures: BMI, diabetes, triglycerides and serum creatinine. The bivariate linkage analysis was completed using an extension of the univariate variance component model [25–27,32], and a test for linkage was conducted using a likelihood ratio test [33] with the multic R library. Diabetes was modelled using a 0–1 indicator variable. For the genome-wide bivariate analyses, a MLS ≥4.00 (P < 0.0001) was considered statistically significant evidence of bivariate linkage and a MLS ≥2.87 (P < 0.001) was considered suggestive evidence of bivariate linkage [34].

Pathway analysis

Pathway analysis was performed to explore uric acid as a polygenic trait affected by genes enriched in canonical pathways related to uric acid metabolism. Pathway analysis was performed separately in each cohort using all QTL with at least suggestive evidence of age–sex-adjusted univariate linkage to uric acid. QTL were defined by the centimorgan (cM) range for a drop of 1.0 LOD on either side of the MLS. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview) build 36.2 was used to map the Marshfield markers to the physical locations closest to the start and end of the QTL. All genes between the two markers were identified. Canonical pathways associated with the set of genes located within the QTL were explored with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems, Inc., Redwood City, CA). With this tool, Fisher's exact test was used to determine if a given pathway was enriched by the genes located within the QTL. For this exploratory analysis, statistical significance was defined as a nominal P < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the study populations are shown in Table 1. In the GENOA cohort, uric acid was 1.0 mg/dL higher (P-value < 0.0001) in men than in women after adjusting for age and race and 0.2 mg/dL (P-value = 0.01) higher in blacks than in whites after adjusting for age and sex. In the HyperGEN cohort, uric acid was 1.2 mg/ dL (P-value < 0.0001) higher in men than in women after adjusting for age and race and 0.3 mg/dL (P-value < 0.0001) higher in blacks than in whites after adjusting for age and sex. Age- and sex-adjusted heritability estimates in the GENOA cohorts were 0.41 ± 0.07 for whites and 0.55 ± 0.07 for blacks and in the HyperGEN cohorts were 0.35 ± 0.06 for whites and 0.35 ± 0.06 for blacks (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic (frequency/mean±SD) | GENOA whites | GENOA blacks | HyperGEN whites | HyperGEN blacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1075 | 1333 | 1542 | 1627 |

| Sibships | 415 | 552 | 612 | 702 |

| Sibling pairs | 1217 | 1380 | 1248 | 983 |

| Singletons | 4 | 24 | 180 | 26 |

| Male (%) | 45 | 30 | 47 | 36 |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 10 | 63 ± 9 | 57 ± 13 | 48 ± 13 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 1.8 |

| Hyperuricaemiaa (%) | 35 | 40 | 27 | 34 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.90 ± 0.27 | 0.90 ± 0.35 | 0.98 ± 0.28 | 1.01 ± 0.49 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 ± 6 | 32 ± 7 | 30 ± 6 | 32 ± 8 |

| Hypertension (%) | 75 | 79 | 80 | 77 |

| Current smoker (%) | 9.3 | 12.5 | 9.0 | 28 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 16 | 29 | 15 | 20 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 160 ± 96 | 120 ± 78 | 165 ± 104 | 113 ± 108 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51 ± 15 | 58 ± 18 | 49 ± 14 | 54 ± 15 |

| Diuretic use (%) | 40 | 45 | 30 | 37 |

| Anti-gout medicationb use (%) | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| Regular aspirin use (%) | 43 | 33 | 20 | 13 |

| Warfarin use (%) | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 1.2 |

| Losartan use (%) | 5.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 1.7 |

| Fenofibrate use (%) | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

aSerum uric acid >7 mg/dL in men and >6 mg/dL in women.

bAllopurinol, colchicine or probenecid.

Table 2.

Heritability (±SE) of uric acid

| Age–sex- | Multivariable- | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Unadjusted | adjusted | adjusted |

| GENOA whites | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.07 |

| GENOA blacks | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.07 |

| HyperGEN whites | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.06 |

| HyperGEN blacks | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.06 |

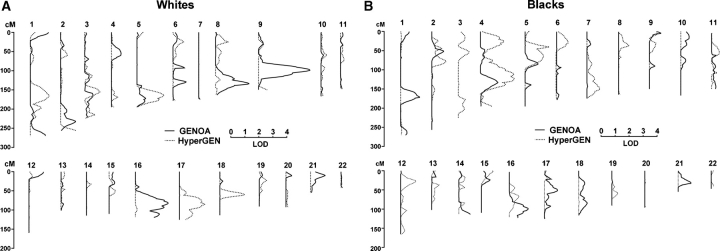

Figure 1 summarizes of the age–sex-adjusted univariate linkage analysis for uric acid. Regions with at least suggestive evidence of linkage [i.e. multipoint logarithm of odds score (MLS) > 2] are presented in Table 3. Significant evidence of linkage (i.e. MLS > 3) on chromosome 9 (MLS = 3.7 at 113 cM) for GENOA whites and suggestive evidence of linkage on chromosome 8 (MLS = 2.4 at 135 cM) and chromosome 16 (MLS = 2.3 at 93 cM) for GENOA whites were not evident in HyperGEN whites (Figure 1A). These QTL were attenuated with multivariable adjustment, with only chromosome 9 in GENOA whites having at least suggestive evidence of linkage (MLS = 2.2 at 111 cM). With multivariable adjustment, suggestive evidence of linkage emerged on chromosome 2 for GENOA whites (MLS = 2.3 at 247 cM, age–sex-adjusted MLS = 1.1 at 237 cM). Suggestive evidence of linkage on chromosome 4 (MLS = 2.4 at 135 cM) for HyperGEN blacks was seen with some evidence of replication at the same region in GENOA blacks (MLS = 1.2 at 145 cM) (Figure 1B). With multivariable adjustment, this QTL was attenuated (MLS = 1.0 at 153 cM), but suggestive evidence of linkage emerged at another loci on chromosome 4 (MLS = 2.1 at 33 cM) in HyperGEN blacks. The meta-analysis combining the results from the GENOA and HyperGEN cohorts showed no evidence of linkage (P > 0.01) at these QTL or any other region of the genome.

Fig. 1.

Summary of linkage analysis of serum uric acid by each chromosomal location (y-axis) and LOD score (x-axis) for (A) whites and (B) blacks (GENOA—solid, HyperGEN—dashed)

Table 3.

Regions with at least suggestive evidence of linkage (MLS ≥2.0) for uric acid (age–sex or multivariable-adjusted)

| Any evidence of replication (LOD ≥0.5 with | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age–sex-adjusted | Multivariable-adjusted | age–sex-adjusted uric acid linkage) | ||||||

| Cohort | Chromosome | Loci (cM) | LOD | Loci (cM) | LOD | Cohort | Loci (cM) | LOD |

| GENOA whites | 8 | 135 | 2.4, P = 0.0005 | 128 | 0.5, P = 0.06 | HyperGEN whites | 135 | <0.5 |

| Framingham | 135 | 1.2a | ||||||

| GENOA whites | 9 | 113 | 3.7, P < 0.0001 | 111 | 2.2, P = 0.0008 | HyperGEN whites | 113 | <0.5 |

| GENOA whites | 16 | 93 | 2.3, P = 0.0005 | 91 | 0.5, P = 0.06 | HyperGEN whites | 93 | <0.5 |

| GENOA blacks | 110 | 1.2, P = 0.008 | ||||||

| GENOA whites | 2 | 237 | 1.1, P = 0.01 | 247 | 2.3, P = 0.0006 | HyperGEN whites | 260 | 1.1, P = 0.02 |

| Framingham | 256 | 1.1a | ||||||

| NHLBI-FHS | 228 | 1.9 | ||||||

| HyperGEN blacks | 4 | 135 | 2.4, P = 0.0004 | 153 | 1.0, P = 0.02 | GENOA blacks | 145 | 1.2, P = 0.008 |

| HyperGEN blacks | 4 | 39 | 1.7, P = 0.003 | 33 | 2.1, P = 0.001 | GENOA blacks | 39 | <0.5 |

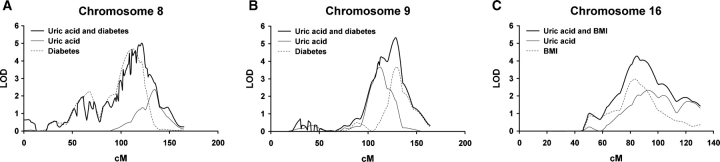

Quantitative trait loci with at least suggestive evidence of bivariate linkage between uric acid and either BMI, diabetes, triglycerides or serum creatinine are presented in Table 4. All three QTLs for univariate uric acid linkage in GENOA whites had significant evidence of linkage in the bivariate linkage analysis (Figure 2). In particular, there was bivariate linkage between uric acid and diabetes on chromosome 8 (MLS = 5.0 at 121 cM) and chromosome 9 (MLS = 5.3 at 129 cM) and between uric acid and BMI on chromosome 16 (MLS = 4.3 at 84 cM). There was suggestive evidence of linkage in HyperGEN blacks between uric acid and BMI on chromosome 4 (MLS = 3.0 at 166 cM) and in GENOA blacks between uric acid and triglycerides on chromosome 14 (MLS = 3.0 at 123 cM). There was also at least suggestive evidence of bivariate linkage between uric acid and serum creatinine at several loci in the GENOA and HyperGEN cohorts.

Table 4.

Regions with at least suggestive evidence of bivariate linkage (MLS ≥ 2.87) and any evidence of univariate uric acid linkage at the same loci (LOD ≥0.5)

| Univariate (uric acid) | Univariate (other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate phenotype | Cohort | Chromosome | Loci (cM) | Bivariate LOD score | LOD score | trait) LOD score |

| Uric acid and BMI | GENOA whites | 9 | 113 | 3.8, P = 0.0001 | 3.7, P < 0.0001 | 0.3, P = 0.10 |

| 16 | 84 | 4.3, P = 0.0001 | 2.0, P = 0.0013 | 2.9, P = 0.0001 | ||

| HyperGEN blacks | 4 | 166 | 3.0, P = 0.0009 | 0.5, P = 0.06 | 0.03, P = 0.36 | |

| Uric acid and diabetesa | GENOA whites | 8 | 121 | 5.0, P < 0.0001 | 1.3, P = 0.008 | 4.0, P < 0.0001 |

| 9 | 129 | 5.3, P < 0.0001 | 1.8, P = 0.002 | 3.6, P < 0.0001 | ||

| Uric acid and triglycerides | GENOA whites | 9 | 113 | 3.8, P = 0.0001 | 3.6, P < 0.0001 | 0.5, P = 0.06 |

| 16 | 123 | 2.9, P = 0.0001 | 1.7, P = 0.003 | 0.2, P = 0.17 | ||

| GENOA Jackson | 14 | 123 | 3.0, P = 0.0009 | 0.7, P = 0.03 | 0.4, P = 0.09 | |

| Uric acid and serum creatinine | GENOA whites | 9 | 113 | 4.6, P < 0.0001 | 3.7, P < 0.0001 | 1.7, P = 0.0023 |

| GENOA blacks | 5 | 85 | 3.4, P = 0.0004 | 0.9, P = 0.020 | 2.0, P = 0.0012 | |

| HyperGEN whites | 17 | 79 | 3.5, P = 0.0003 | 1.6, P = 0.0033 | 2.2, P = 0.0007 | |

| HyperGEN blacks | 7 | 155 | 3.2, P = 0.0006 | 0.9, P = 0.021 | 1.7, P = 0.0024 |

aQualitative linkage analysis used for the univariate diabetes phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Multipoint LOD scores of age–sex-adjusted linkage plots in GENOA whites for (A) chromosome 8, (B) chromosome 9 and (C) chromosome 16. Thin curve is for univariate linkage to uric acid. Dashed curve is for univariate linkage to the surrogate of insulin resistance. Thick curve is for the bivariate linkage to uric acid and the surrogate of insulin resistance. BMI—body mass index.

Ingenuity pathway analysis was performed in each cohort using all QTL with at least suggestive evidence of age–sex-adjusted linkage to uric acid. For GENOA whites, the physical location of the three QTL were chromosome 8, 120 M bp to 129 M bp; chromosome 9, 93 M bp to 112 M bp; and chromosome 16, 57 M bp to 80 M bp. In these regions a total of 437 genes were identified. Pathway analysis using these ‘focus genes’ identified six enriched pathways and three of these pathways contained genes at two different QTLs: fructose and mannose metabolism (P = 0.013), inositol metabolism (P = 0.020) and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis (P = 0.045). For HyperGEN blacks, the physical location of the QTL was chromosome 4, 97 M bp to 158 M bp; from which 339 genes were identified. There were eight enriched pathways: seven pathways involving the alcohol dehydrogenase superfamily of genes and the coagulation system pathway. The purine metabolism pathway was borderline significant for enrichment (P = 0.11).

Discussion

Among family members with similar serum uric acid levels, there were genomic regions where family members were more likely to share the same alleles (i.e. linkage). For GENOA whites, genome-wide significant evidence of linkage for uric acid was found on chromosome 9 (113 cM) and suggestive evidence of linkage on chromosomes 8 (135 cM) and 16 (93 cM), but these QTL did not replicate in HyperGEN whites. All three QTL showed genome-wide significant evidence of linkage (MLS > 4.0) in bivariate analysis with uric acid and a surrogate of insulin resistance (Figure 2). For HyperGEN blacks, there was suggestive evidence of linkage for uric acid on chromosome 4 (135 cM) that showed some evidence of replication in GENOA blacks.

Other investigators have performed genome-wide linkage analysis for uric acid levels. Evidence for replication of the findings in this study with the findings by other investigators is shown in Table 3. In the Framingham Heart Study, there was evidence of linkage (MLS = 3.3) on chromosome 15 (50 cM) [9], but this QTL was not replicated in the GENOA or HyperGEN cohorts. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study found evidence of linkage (MLS = 3.3) on chromosome 2 (240 cM) for a composite measure of uric acid and seven other surrogates of insulin resistance [11]. This QTL did show some evidence of replication in both GENOA and HyperGEN whites (Table 3) and in the Framingham Heart Study (MLS = 1.1 at 256 cM) [9]. At this locus (2q37.3), positional cloning implicated the CAPN10 gene as a type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene [35,36]. Other studies have not confirmed this association and the mechanism for diabetes risk is unknown [37]. The San Antonio Family Heart Study (Mexican Americans) found evidence of linkage (MLS = 3.3) for uric acid on chromosome 6 (133 cM) [10]. There was some evidence of replication of this locus in GENOA whites (MLS = 0.9 at 138 cM), but not in HyperGEN whites.

In this study, the loci with the most statistically significant evidence for uric acid linkage were on chromosomes 8, 9 and 16 in the GENOA white cohort. These QTL also showed evidence of pleiotropy between uric acid and surrogates of insulin resistance, and the QTL on chromosome 9 also showed pleiotropy between uric acid and serum creatinine (Table 4). Genes in the fructose and mannose metabolism pathway were enriched at these QTL. The enriched genes were aldolase B (9q21.3-q22.2), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1 (9q22.3), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (9q22.3) and fucokinase (16q22.1). Fructose is the only dietary sugar that raises uric acid levels in humans [38]. The development of high-fructose corn syrup may be a major contributor to the increased prevalence of obesity, diabetes and hypertension [15,39,40]. By raising uric acid levels, fructose interferes with glucose uptake by muscles and contributes to insulin resistance [15]. The liver responds to a fructose load by sequestration of inorganic phosphate in fructose-1-phosphate leading to decreased ATP synthesis. Decreased ATP synthesis leads to increased inosine, a precursor to uric acid [14]. Of the four genes enriched in the fructose and mannose metabolism pathway, aldolase B is known to have an associated genetic disorder leading to hyperuricaemia. Aldolase B deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that presents clinically with failure to thrive and fast-induced hypoglycaemia. Heterozygotes for aldolase B deficiency have a greater rise in uric acid levels after ingestion of fructose than that in controls [41]. It is plausible that heterozygotes for aldolase B deficiency or other aldolase B variants explain the QTL found on chromosome 9.

There was suggestive evidence of linkage of uric acid to a locus on chromosome 4 at 135 cM in HyperGEN blacks with evidence of replication in GENOA blacks. This QTL also showed suggestive evidence of pleiotropy with a surrogate of insulin resistance (BMI). While only borderline significant (P = 0.11) for enrichment, purine metabolism is a biologically plausible pathway to account for this QTL since uric acid is the end-product of purine metabolism. The purine metabolism pathway genes were GUCY1A3, GUCY1B3, PAPSS1, PDE5A and SMARCA5, but none have a reported association with hyperuricaemia or insulin resistance. Pathways containing alcohol dehydrogenase genes were enriched at this QTL, in part, because seven members of this gene family are contiguous at this locus. There was also suggestive evidence of multivariable-adjusted linkage to uric acid on chromosome 4 at 33 cM in HyperGEN blacks, but without evidence of replication in GENOA blacks. The SLC2A9 gene, a glucose, fructose and uric acid transporter gene associated with serum uric acid levels [16–18], is located near this locus on chromosome 4 at 21 cM [age–sex-adjusted log of the odds (LOD) score = 0.9, P = 0.02; multivariable-adjusted LOD score = 1.2, P = 0.01]. Functional polymorphism in the SLC2A9 gene may have caused the linkage in HyperGEN blacks near this locus.

This study and other studies that have identified QTL with linkage to uric acid or QTL with pleiotropic effects between uric acid and other surrogates of insulin resistance have had limited replication. Unlike prior studies, the cohorts used in this study were composed of families characterized by two or more siblings with hypertension. The reason for lack of replication of the findings between GENOA whites and HyperGEN whites is not known. There were differences between the two networks with respect to how the hypertensive subjects were identified, inclusion of normotensive siblings and the multigenerational structure of the families. Instead of large effects of a few genes, small effects of many genes with differences in gene–environment and gene–gene interactions between networks may have contributed to lack of replication [37]. Restricting the biological pathways that influence the phenotype, such as studying the urinary fractional excretion of urate, may improve replication between studies.

Strengths of this study include linkage analysis in two separate networks allowing independent assessment for evidence of replication. In addition, heritability and linkage analysis of uric acid was performed in both non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white cohorts. Family-based studies using non-elderly hypertensive probands are particularly relevant given the potential link between hyperuricaemia and the early development of primary hypertension [42]. The pathway analysis provided a systematic approach to identifying candidate genes under uric acid QTLs.

There were also several limitations to this study. Dietary data were not available, and dietary purines are known to have a large influence on serum uric acid levels. Diuretic medication use was common, as expected in families enriched for hypertension, but adjustment for diuretic use in the analyses may not have adequately accounted for all the variability in uric acid due to different diuretic types and doses. The genetic effects on uric acid over a lifetime may not be adequately captured with a single uric acid level. The QTL for uric acid identified in GENOA whites and HyperGEN blacks were attenuated with multivariable adjustment. Both age–sex-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted uric acid phenotypes are relevant. Several disease pathways that may be affected by uric acid levels can be overadjusted for, including insulin resistance, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and kidney disease [3].

In conclusion, QTLs for uric acid with evidence of pleiotropic effects on other surrogates of insulin resistance or serum creatinine were identified on chromosomes 8, 9 and 16 in white families. Genes in the fructose metabolism pathway were enriched at these loci, providing a plausible biological mechanism that may underlie these findings. Quantitative trait loci for uric acid on chromosome 4 were found in blacks, with one locus that showed some evidence of replication and another locus in the region of the SLC2A9 gene. These loci could be explored further with positional cloning or candidate gene association studies. However, given the overall lack of replication of loci for uric acid identified with linkage analysis, alternative approaches may be needed. Genome-wide association studies have shown successful replication of loci for uric acid and may be the optimal approach for identifying genomic regions that influence uric acid levels.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK073537, K23 DK078229).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Lin KC, Lin HY, Chou P. Community based epidemiological study on hyperuricemia and gout in Kin-Hu, Kinmen. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman JP, Choi H, Curhan GC. Plasma uric acid level and risk for incident hypertension among men. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:287–292. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Short RA, Tuttle KR. Clinical evidence for the influence of uric acid on hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease: a statistical modeling perspective. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson RJ, Segal MS, Srinivas T, et al. Essential hypertension, progressive renal disease, and uric acid: a pathogenetic link? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1909–1919. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, et al. Uric acid and incident kidney disease in the community. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1204–1211. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obermayr RP, Temml C, Gutjahr G, et al. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2407–2413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilk JB, Djousse L, Borecki I, et al. Segregation analysis of serum uric acid in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Hum Genet. 2000;106:355–359. doi: 10.1007/s004390000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice T, Borecki IB, Bouchard C, et al. Commingling analysis of regional fat distribution measures: the Quebec Family Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16:831–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Q, Guo CY, Cupples LA, et al. Genome-wide search for genes affecting serum uric acid levels: the Framingham Heart Study. Metabolism. 2005;54:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nath SD, Voruganti VS, Arar NH, et al. Genome scan for determinants of serum uric acid variability. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang W, Miller MB, Rich SS, et al. Linkage analysis of a composite factor for the multiple metabolic syndrome: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:2840–2847. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RR, Rao DC, Ellison RC, et al. NHLBI family blood pressure program: methodology and recruitment in the HyperGEN network. Hypertension genetic epidemiology network. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:389–400. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Wang QJ. The prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension among US adults according to the new joint national committee guidelines: new challenges of the old problem. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2126–2134. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayes PA. Intermediary metabolism of fructose. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:754S–765S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.754S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinig M, Johnson RJ. Role of uric acid in hypertension, renal disease, and metabolic syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:1059–1064. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.12.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley RN, Wang C, Ishani A, et al. NHANES III: influence of race on GFR thresholds and detection of metabolic abnormalities. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2575–2582. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace C, Newhouse SJ, Braund P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genes for biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: serum urate and dyslipidemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, et al. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet. 2008;40:437–442. doi: 10.1038/ng.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa T, Mazzali M, Kang DH, et al. Uric acid—a uremic toxin? Blood Purif. 2006;24:67–70. doi: 10.1159/000089440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Santamaria J, et al. Mild hyperuricemia induces vasoconstriction and maintains glomerular hypertension in normal and remnant kidney rats. Kidney Int. 2005;67:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Rochester Epidemiology Project: a unique resource for research in the rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30:819–34, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner ST, Kardia SL, Mosley TH, et al. Influence of genomic loci on measures of chronic kidney disease in hypertensive sibships. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2048–2055. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rock RC, Walker WG, Jennings CD. Nitrogen metabolites and renal function. In: TIetz NW, editor. Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1987. pp. 684–686. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amos CI. Robust variance-components approach for assessing genetic linkage in pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:535–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopper JL, Mathews JD. Extensions to multivariate normal models for pedigree analysis. Ann Hum Genet. 1982;46:373–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1982.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobel E, Lange K. Descent graphs in pedigree analysis: applications to haplotyping, location scores, and marker-sharing statistics. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:1323–1337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobel E, Sengul H, Weeks DE. Multipoint estimation of identity-by-descent probabilities at arbitrary positions among marker loci on general pedigrees. Hum Hered. 2001;52:121–131. doi: 10.1159/000053366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton NE. Significance levels in complex inheritance. [Erratum appears in Am J Hum Genet 1998;63(4):1252] Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:690–697. doi: 10.1086/301741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wise LH, Lanchbury JS, Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of genome searches. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:263–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6330263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams JT, Van Eerdewegh P, Almasy L, et al. Joint multipoint linkage analysis of multivariate qualitative and quantitative traits: I. likelihood formulation and simulation results. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1134–1147. doi: 10.1086/302570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Self S, Liang KY. Asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators and likelihood ratio tests under nonstandard conditions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:605–610. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner ST, Kardia SL, Boerwinkle E, et al. Multivariate linkage analysis of blood pressure and body mass index. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;27:64–73. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanis CL, Boerwinkle E, Chakraborty R, et al. A genome-wide search for human non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes genes reveals a major susceptibility locus on chromosome 2. Nat Genet. 1996;13:161–166. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horikawa Y, Oda N, Cox NJ, et al. Genetic variation in the gene encoding calpain-10 is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2000;26:163–175. doi: 10.1038/79876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barroso I. Genetics of Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:517–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emmerson BT. Effect of oral fructose on urate production. Ann Rheum Dis. 1974;33:276–280. doi: 10.1136/ard.33.3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. [See comment] JAMA. 2004;292:927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaby AR. Adverse effects of dietary fructose. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:294–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oberhaensli RD, Rajagopalan B, Taylor DJ, et al. Study of hereditary fructose intolerance by use of 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lancet. 1987;2:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia in childhood primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:247–252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085858.66548.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]