Key findings

SLC2A9 was recently cloned and identified as a member of the SLC2A gene family of hexose facilitative transporters, where its main physiological role was assumed to be in the transport of glucose and fructose. However, new findings have unearthed a novel role for SLC2A9 (also known as GLUT9) as a modulator of uric acid levels. Specifically, after conducting genome-wide scans, Doring et al. and Vitart et al. have identified several noncoding genetic variants of SLC2A9 that were strongly associated with a decrease in serum uric acid concentrations and an increase in fractional excretion of uric acid. Accordingly, the variants were also associated with a decreased risk of gout, suggesting a protective role for the minor alleles. Interestingly, in both of the studies, gender-specific effects were more pronounced in women than in men. Doring et al. estimated the additive effect to be −0.45 mg/ dl per copy of the minor allele in women and −0.25 mg/ dl in men. Overall, genetic variants of SLC2A9 are potentially responsible for 1.2–6.0% of the variance in serum uric acid concentrations. Of importance is the functional determination that SLC2A9 is a strong urate transporter, implicating it as a key player in the renal excretion of uric acid that could greatly impact clinical practices.

Brief review

Unlike most mammals, humans cannot regulate uric acid levels very effectively, largely because of the mutational loss of uricase (urate oxidase) that degrades uric acid to allantoin. A major consequence of the lack of this hepatic enzyme is a relatively unique susceptibility of humans to develop hyperuricemia in response to diet, such as from purine-rich meats, seafood and beer. In addition, fructose, which is present in table sugar or sucrose, the sweetener high fructose corn syrup and fruits, can raise uric acid levels due to the unique ability of this sugar to cause intracellular ATP depletion and adenine nucleotide turnover.

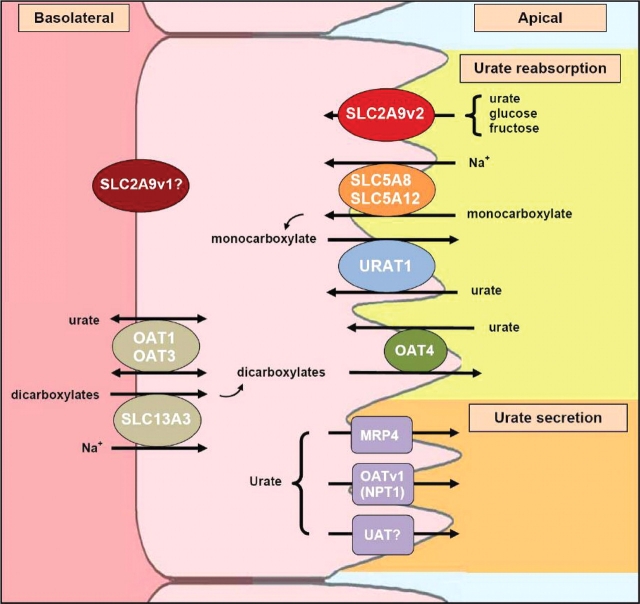

While diet is likely a key factor in modulating uric acid levels in the population, genetic mechanisms are also known to be important regulators of uric acid concentrations which is considered to be strongly heritable, ranging from 25 to 73% [1,2]. Some rare genetic causes of hyperuricemia include those associated with the de novo purine synthesis pathway, such as complete or partial deficiency in hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase and increased phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase (PRPP). More recently, the disease, familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy (FJHN), was found to be due to mutation in uromodulin (Tamm Horsfall protein). Although elevated uric acid can be caused by the increased breakdown of endogenous and exogenous purines, impairments of the renal excretion of uric acid is the main cause of ∼90% of all hyperuricemia incidents; thus, it is more clinically significant [3,4]. Renal transport of uric acid is governed by a complex system of transporters in the proximal tubule (Figure 1) [4,5]. Several genetic polymorphisms in the apical transporter, URAT1, have already been linked with hyperuricemia [6,7]. In addition, mutational loss of URAT1 can cause the rare syndrome of hypouricemia with exercise-induced acute renal failure [8].

Fig. 1.

Urate transport in the proximal tubule. Several transporters have recently been identified as potential molecular components in the renal transport of urate [4,5]. URAT1, a urate-anion exchanger, and OAT4, an organic anion-dicarboxylate exchanger, are mediators of urate reabsorption. URAT1 is considered to be a key player in uric acid homeostasis and has been estimated to be responsible for 50% of urate reabsorption. Its activity, however, is driven by sodium-anion transporters, potentially by SLC5A8 and SLC5A12, which provide the main source of anions needed for URAT1 function. For urate secretion into the lumen, a urate transporter/channel (UAT), a voltage-driven organic anion transporter (OATv1 or NPT1) and an ATP-binding cassette transporter (MRP4) are potential efflux candidates. Although very little is known about the basolateral transport of urate, two anion-dicarboxylate transporters, OAT1 and OAT3, have been shown to have the ability to transport urate, but the direction of the urate transport still needs to be characterized. Furthermore, their activity may be coupled with SLC13A3 that drives the intake of Na+ and dicarboxylates. In addition to all these transporters, SLC2A9 has been discovered to be a candidate protein in the excretion of urate and may play a dominant role in urate reabsorption [12]. The short isoform, SLC2A9v2, localizes exclusively to the apical membrane and has been shown to transport urate. The role of the long isoform, SLC2A9v1, on the uric acid transport remains to be elucidated.

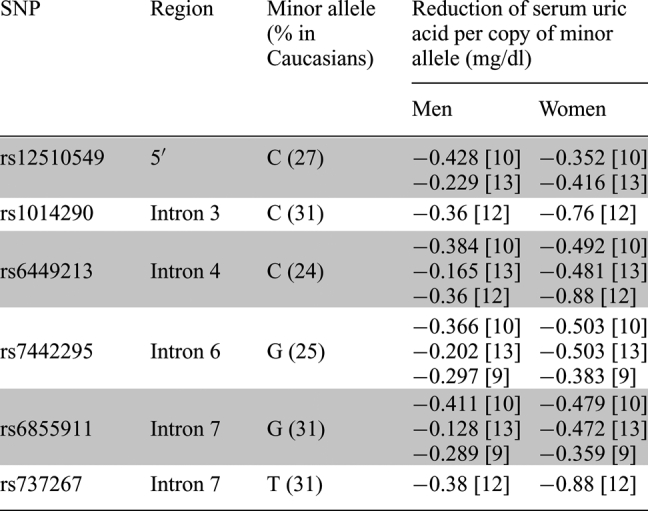

Recently, genome-wide studies have been conducted to identify new genes involved in uric acid homeostasis. Several loci associated with hyperuricemia have been identified, including in chromosome 4q25 observed in Taiwanese aborigines [4], in chromosomes 2, 8 and 15 in the Framingham Heart Study [2] and in chromosome 6q22–23 in Mexican Americans [1]. However, one of the most striking associations was localized to SLC2A9 on chromosome 4p15.3–16. After conducting genome-wide scans by utilizing chips consisting of 300K–500K single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), genetic variants of SLC2A9 were strongly associated with reduced levels of serum uric acid in Caucasian cohorts from Italy [9,10], the UK [11], Croatia [12], the United States [10], Germany and Austria [13]. The strongest associations were mapped to noncoding SNPs located near the 5′ of the gene and within introns 3–7, but further studies are needed to elucidate their impact on the protein's function. Interestingly, SLC2A9 polymorphisms (rs6855911, rs7442295, rs6449213, rs12510549, rs737267 and rs1014290) were shown to have gender-specific effects on uric acid concentrations, resulting in a greater reduction in women (−0.352 to −0.880 mg/dl) than in men (−0.128 to −0.428 mg/dl) (Table 1). Consequently, genetic variants of SLC2A9 are potentially responsible for 5.3–6.0% of the variance in serum uric acid concentrations in women and 1.2–1.7% in men.

Table 1.

SLC2A9 SNPs showing gender-specific effects on serum uric acid concentrations

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of SLC2A9 have been reported from various genome-wide association studies to cause gender-specific differences in serum uric acid levels. All six mutations were located in noncoding regions of the gene: five polymorphisms were in intronic regions and one polymorphism was located 5′ of the SLC2A9 gene sequence. Mutations in the gene caused a greater additive effect in women than in men. For women with one copy of the minor allele, the effect size ranged from −0.359 to −0.88 mg/dl. For men, the effect size ranged from −0.128 to −0.428 mg/dl. If an individual has two copies of the minor allele, the reduction in serum uric acid levels would generally double. The frequencies of these mutations are relatively common, affecting ∼24–31% of the Caucasian population.

How do alterations in SLC2A9 alter serum uric acid levels? Recent studies suggest that one mechanism may be by modulating renal excretion of uric acid. There are two common variants of SLC2A9 (GLUT9): a long isoform (SL2A9v1) and a short isoform (SLC2A9v2) [14]. From in vitro studies, it was shown that the long isoform trafficked predominantly to the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule epithelial cells while the short isoform was exclusively localized to the apical membrane. Utilizing Xenopus laevis oocytes, SLC2A9v2 was shown to have a high capacity for the urate transport [12]. Polymorphisms of SLC2A9 were also shown to be associated with the increased fractional excretion of uric acid, suggesting that these polymorphisms may effectively modulate uric acid excretion.

Discussion

There is a growing interest in understanding the genetic determinants of urate homeostasis due to the concern that elevated serum uric acid concentrations may be a risk factor for several common disorders, including gout, hypertension [15], metabolic syndrome [16,17], cardiovascular disease [18], type 2 diabetes mellitus [19], diabetic nephropathy [20] and kidney disease [21,22]. The discovery of SLC2A9, along with other proteins involved in the urate transport, may greatly impact our understanding of uric acid homeostasis. Clinically, new insights in this field can enhance the utilization of current medications and can generate novel genetic therapeutic targets for the control of uric acid concentrations. For instance, with the discovery of URAT1, the assumed action of pyrazine carboxylic acid (PZA) as an inhibitor of urate secretion has been debunked. Instead, PZA has been shown increase urate reabsorption by stimulating URAT1 activity, thus invalidating the four-component model of the renal urate transport [4].

Since fructose itself results in uric acid generation, the observation that SLC2A9, a fructose transporter, can also function as a urate transporter raises the interesting possibility that this transporter may ‘fine tune’ the movement of uric acid in and out of the cell in response to fructose. For example, a polymorphism of SLCA29 could lead to a relatively higher concentration of uric acid within the cell in response to fructose. The importance of this potential function could be significant given recent studies suggesting that fructose-induced hyperuricemia may have a critical role in mediating the metabolic syndrome [23] and by studies suggesting that intracellular uric acid levels may largely mediate many of the pro-inflammatory effects of uric acid in various cell types [24]. Besides being expressed in a variety of other sites, such as the liver, placenta, brain, lung and leukocytes, SLC2A9 is also expressed in chrondrocytes [12,14,25]. Can SLC2A9 be responsible for the buildup of urate in gouty arthritis?

Combined with its strong activity as a urate transporter and the strong associations between genetic variants of SLC2A9 and serum uric acid concentrations, SLC2A9 is an important modulator of uric acid levels. Interestingly, it was the minor alleles of the genetic variants of SLC2A9 that was associated with reduced levels of serum uric acid levels. Assuming that the mutations impair the function of the protein, SLC2A9 is then implicated as an essential player in inducing hyperuricemia in humans. Thus, individuals with the mutations are protected and less likely to develop gout and potentially other disorders. Furthermore, SLC2A9 may be important to the underlining differences in uric acid concentrations reported between women and men.

Take home message

Serum uric acid levels and renal uric acid excretion have been found to be modulated by genetic polymorphisms in SLC2A9, a fructose transporter, which can influence the risk for gout by affecting renal urate reabsorption.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH training grant NIDDK T32-7518 (to M. Le), NIH RO-1 HL-68607 and generous funds from Gatorade.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Nath SD, Voruganti VS, Arar NH, et al. Genome scan for determinants of serum uric acid variability. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3156–3163. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Q, Guo CY, Cupples LA, et al. Genome-wide search for genes affecting serum uric acid levels: the Framingham Heart study. Metabolism. 2005;54:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terkeltaub R, Bushinsky DA, Becker MA. Recent developments in our understanding of the renal basis of hyperuricemia and the development of novel antihyperuricemic therapeutics. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/ar1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mount DB, Kwon CY, Zandi-Nejad K. Renal urate transport. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32:313–331. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2006.02.006. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anzai N, Kanai Y, Endou H. New insights into renal transport of urate. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:151–157. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328032781a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graessler J, Graessler A, Unger S, et al. Association of the human urate transporter 1 with reduced renal uric acid excretion and hyperuricemia in a German Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:292–300. doi: 10.1002/art.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vazquez-Mellado J, Jimenez-Vaca AL, Cuevas-Covarrubias S, et al. Molecular analysis of the SLC22A12 (URAT1) gene in patients with primary gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:215–219. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichida K, Hosoyamada M, Hisatome I, et al. Clinical and molecular analysis of patients with renal hypouricemia in Japan-influence of URAT1 gene on urinary urate excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:164–173. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000105320.04395.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Sanna S, Maschio A, et al. The GLUT9 gene is associated with serum uric acid levels in sardinia and chianti cohorts. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandstätter A, Kiechl S, Kollerits B, et al. The gender-specific association of the putative fructose transporter SLC2A9 variants with uric acid levels is modified by BMI. Diabetes Care. 2008 doi: 10.2337/dc08-0349. May 16 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace C, Newhouse SJ, Braund P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genes for biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: serum urate and dyslipidemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, et al. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet. 2008;40:437–442. doi: 10.1038/ng.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doring A, Gieger C, Mehta D, et al. SLC2A9 influences uric acid concentrations with pronounced sex-specific effects. Nat Genet. 2008;40:430–436. doi: 10.1038/ng.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Augustin R, Carayannopoulos MO, Dowd LO, et al. Identification and characterization of human glucose transporter-like protein-9 (GLUT9): alternative splicing alters trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16229–16236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson RJ, Titte S, Cade JR, et al. Uric acid, evolution and primitive cultures. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conen D, Wietlisbach V, Bovet P, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and relation of serum uric acid with cardiovascular risk factors in a developing country. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE. Components of the metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in beaver dam. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1790–1794. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, et al. Uric acid is a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2006;37:1503–1507. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221716.55088.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dehghan A, van Hoek M, Sijbrands EJ, et al. High serum uric acid as a novel risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:361–362. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosolowsky ET, Ficociello LH, Maselli NJ, et al. High-normal serum uric acid is associated with impaired glomerular filtration rate in nonproteinuric patients with type 1 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:706–713. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04271007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, et al. Uric acid and incident kidney disease in the community. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chonchol M, Shlipak MG, Katz R, et al. Relationship of uric acid with progression of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:239–247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa T, Hu H, Zharikov S, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F625–F631. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00140.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang DH, Park SK, Lee IK, et al. Uric acid-induced C-reactive protein expression: implication on cell proliferation and nitric oxide production of human vascular cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3553–3562. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phay JE, Hussain HB, Moley JF. Cloning and expression analysis of a novel member of the facilitative glucose transporter family, SLC2A9 (GLUT9) Genomics. 2000;66:217–220. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]