Abstract

Introduction:

Rheumatism has been treated using whole-body cryotherapy (WBCT) since the 1970s. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of WBCT as an experimental, adjunctive method of treating depressive and anxiety disorders.

Materials and Methods:

A control (n=34) and a study group (n=26), both consisting of outpatients 18–65 years old with depressive and anxiety disorders (ICD-10), received standard psychopharmacotherapy. The study group was additionally treated with a series of 15 daily visits to a cryogenic chamber (2–3 min, from –160°C to –°C). The Hamilton’s depression rating scale (HDRS) and Hamilton’s anxiety rating scale (HARS) were used as the outcome measures.

Results:

After three weeks, a decrease of at least 50% from the baseline HDRS-17 scores in 34.6% of the study group and 2.9% of the control group and a decrease of at least 50% from the baseline HARS score in 46.2% of the study group and in none of the control group were noted.

Conclusions:

These findings, despite such limitations as a small sample size, suggest a possible role for WBCT as a short-term adjuvant treatment for mood and anxiety disorders.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, adjuvant therapy, experimental treatment method, whole-body cryotherapy

Introduction

Treatment using total immersion of the body in extremely low temperatures was first introduced in Japan towards the end of the 1970s by Prof. Toshiro Yamauchi [21], who constructed the first cryogenic chamber and successfully used cryotherapy to treat rheumatism. Whole-body cryotherapy (WBCT) is currently used to alleviate inflammation and pain in arthritis [2] and osteoarthritis [8] and for pain relief in fibromyalgia [10, 17]. WBCT has been found useful in neurological diseases in reducing spasticity [20], as a method of kinesitherapy in rheumatic diseases and multiple sclerosis, and for its sedative effect in psoriasis and neurodermatitis [2].

It has already been demonstrated that WBCT applied for short times stimulates physiological reactions of an organism which result in analgesic, anti-swelling, and hormonal, immune, and circulatory system reactions [14, 18, 23]. When the time of exposure to extremely low temperatures is strictly controlled, cryotherapy does not cause any significant reactions from the circulatory system and is thus safe [18]. Cryogenic chamber treatment does not affect heart rate, blood pressure, or left ventricle fractional shortening index and its ejection, or cause arrhythmia and ischemic changes of the heart [22]. Although WBCT may induce a transient bronchodilatory effect [1], the results of Smolander et al. [19] did not support the hypothesis that the WBCT improves lung function. WBCT induced minor bronchoconstriction in healthy humans and therefore it did not seem to be harmful to lung function. However, WBCT should be applied with caution in susceptible individuals, such as asthmatics.

The only animal study assessed the effect of short exposure to extremely low temperature on some plasma and liver enzymes in rats [12]. Statistically significant increases in the activities of glutamate dehydrogenase, sorbitol dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, ornithine transcarbamoylase, and arginase were observed in the plasma and liver. The results indicate the influence of low temperature on liver metabolism, which may lead to changes in the metabolism of drugs.

Apart from activating the body’s system of temperature regulation, there is also a hormonal response, which increases body metabolism and the concentrations of adrenaline, noradrenaline, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisone, pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), and β-endorphins in blood plasma as well as male testosterone levels [15, 23]. In a recent study assessing blood serum concentrations of selected steroid hormones in professional football players subjected to WBCT, the authors suggested that it leads to a significant decrease in serum testosterone and estradiol, with no effect on dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and luteinizing hormone levels. The changes observed are probably due to cryotherapy-induced changes in the blood supply to the skin and subcutaneous tissue as well as to modulation of the activity of aromatase, which is responsible for the conversion of testosterone and androstendione to estrogens [7].

POMC is the source of several important biologically active substances, such as ACTH in the anterior pituitary gland and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and β-endorphin in the intermediate lobe. α-MSH has a role in the regulation of appetite and sexual behavior. One neurobiological hypothesis of depression is based largely on dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The brain’s opioid peptide systems are known to play an important role in motivation, emotion, attachment behavior, response to stress and pain, and the control of food intake [9]. The positive effects of WBCT in treating both external and internal pain are due to the activation of the endogenous opioid system and “pain control system” [15]. It is possible that such a multi-system reaction could play a role in the treatment of mental disorders [16]. WBCT is successfully used in clinical work in several countries; however, very limited data are available.

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that WBCT may be a novel adjunctive therapy for affective and anxiety disorders.

Materials and Methods

This study was based on the assessment of depressive and anxiety symptoms observed in a group of subjects exposed to WBCT compared with a control group. The study, whose protocol was accepted by the local bioethics commission, was carried out at the Department of Psychiatry of Wrocław Medical University.

Subjects

Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: circulatory or breathing insufficiency, clotting, embolism, inflammation of blood vessels, open wounds, ulcers, serious cognitive disturbances, fever, addictions, claustrophobia, and over-sensitivity to cold. The study involved persons from 18–65 years of age with depressive and anxiety disorders (ICD-10 criteria) treated at an outpatient psychiatric clinic, after they had provided written informed consent. The subjects in both the control group (n=34) and the study group (n=26) received standard psychopharmacotherapy as prescribed by their psychiatrists (Table 1). This treatment was not modified during the evaluation period.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the samples

| Study group (n=26) | Control group | p-value (n=34) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of females | 22(84.6%) | 31(91.2%) | NS |

| Average age | 47.04(SD=13.05) | 40.88(SD=11.90) | NS |

| Marital status: | |||

| single | 5(19.2%) | 6(18.2%) | |

| in a relationship | 17(65.4%) | 21(61.8%) | NS |

| separated/divorced | 4(15.4%) | 7(20.6%) | |

| Number with children | 17 | 25 | NS |

| Number living alone | 3(11.5%) | 3(8.8%) | NS |

| Level of education: | |||

| primary | 1 | 1 | 0.001 |

| vocational | 3 | 17 | |

| high school | 11 | 15 | |

| university | 9 | 1 | |

| Number employed | 7(28.0%) | 7(20.6%) | NS |

| Diagnosis (ICD-10): | |||

| F3 | 14(53.8%) | 20(58.8%) | NS |

| F4 | 12(46.2%) | 14(41.2%) | NS |

| Pharmacotherapy: | NS | ||

| classical thymoleptics | 13 | 14 | |

| new thymoleptics | 7 | 13 | |

| benzodiazepines | 14 | 17 | |

| neuroleptics | 5 | 7 |

NS - not significant.

Method

The subjects in the study group were additionally treated using a cycle of 15 visits to a cryogenic chamber carried out daily from Monday to Friday. The cryogenic chamber has two rooms: the vestibule, in which the temperature is −60°C, and the main chamber, where the temperature can be set anywhere between −110 and −160°C. The external walls are covered with multi-layer isolation to maintain low temperatures and the outer surface is kept at room temperature. Liquid nitrogen is used as the coolant. The functioning of the cryogenic chamber is entirely automated and the main working parameters are controlled by two electronic mechanisms. The sessions in the chamber lasted 2–3 min. The temperature used in the chamber during the first visit was −110°C. This temperature was systematically lowered over successive visits to permit the organism to adapt to the low temperatures. The temperature used during the final visit was −160°C. The patients stood inside the chamber in swimwear with their noses and mouths secured by a surgical mask lined on the inside with two layers of gauze, their ears covered by a woolen headband and their feet in woolen socks and wooden clogs. Gregorowicz and Zagrobelny [3] provide guidance on the appropriate duration of exposure and temperature for adult patients as well as a list of medical conditions for which WBCT is unsuitable.

Observations were made at six different stages: at the start of treatment (T1), after 7, 14, and 21 days (T2, T3, and T4, respectively), as well as 3 and 6 months after the cycle of visits (T5 and T6, respectively). This article considers the short-term effects of treatment (the first three weeks, T1–T4). Apart from standard medical documentation, the study used Hamilton’s scales of depression and anxiety.

The 17-item Hamilton’s depression rating scale (HDRS-17) is used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms and provides a valuable guide of a patient’s progress over time [5]. Items are scored 0–4 and, in general, the higher the total score the more severe the depression. Questions are related to symptoms such as the patient’s mood, guilt feelings, thoughts of suicide, disturbed sleep, anxiety levels, and weight loss. The original HDRS-17 has often been reported to be the most sensitive scale for measuring response to treatment and is probably the most widely used scale in research on depression for describing levels of severity in different groups, ensuring adequate matching for measuring improvements in clinical trials.

The Hamilton’s anxiety rating scale (HARS) was one of the first rating scales developed to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms [6]. The scale includes 13 symptoms regarding: moods of anxiety, tension, and fear, insomnia, cognitive changes, depression, and somatic symptoms of a general type and of the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic systems. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale. The measure of anxiety is the sum of the scores for each item. The five scores are: none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3), and very severe (4). This is a widely used scale and an accepted outcome measure in clinical trials.

Outcome measure

Two criteria for determining the short-term efficacy of WBCT as an adjunctive treatment according to either the HDRS-17 or HARS score were used.

Criterion 1: i) a reduction in the given score should be significantly greater in the study group than in the control group, and ii) the mean of the given score in the study group must be lower at the endpoint. The first condition is insufficient as an indicator of effectiveness, since it is easier to reduce a high score than a low score.

Criterion 2: a positive response to treatment after three weeks according to a score was defined as at least a 50% reduction from the baseline score at the endpoint. WBCT is considered effective if the proportion of patients with a positive response in the study group is significantly greater than in the control group.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test for independence was used to test whether there was a significant difference between the proportions of patients showing a decrease of 50% in these scores over a 3-week period. The Mann-Whitney rank test for independent samples was used to compare changes in HDRS-17 and HARS in the two groups from the baseline scores, since these changes did not fit the normal distribution (e.g. the hypothesis of the normality of the change from the baseline of the depression score was rejected using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with p<0.01, p<0.05, and p<0.01 for the changes after one, two, and three weeks, respectively). Similarly, the Wilcoxon rank test for dependent samples was used to test for a significant change in these scores within a group. Linear regression was used to compare the rate of change of these scores according to the group and clinical variables. Regression models were also used to assess the effects of the two methods of treatment on the HDRS-17 and HARS scores (dependent variables), taking into account both sociodemographic and clinical factors (explanatory variables: age, sex, marital status, having children, employment, diagnosis, and treatment type). It was assumed that each variable could be associated with the initial assessment as well as the rate of change of the assessment.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical data regarding the patients are presented in Table 1. The only significant difference between the groups was the level of education. There was a large majority of females in both groups, but there was no significant difference between the sex proportions in the two groups (Table 1).

In the following section, changes in the HARS and HDRS-17 scores within the groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test and comparisons of these changes between the groups was carried out using the Mann-Whitney test. According to the Wilcoxon test, in the first week (T1–T2) significant decreases in the HDRS-17 (Z= −3.678, p<0.001) and HARS (Z= −3.730, p<0.001) scores were observed in the study group, as opposed to the control group (Z= −0.700, p>0.4 and Z= −0.778, p>0.4, respectively). The statistical comparison of the average decrease in the scores within groups is central to testing the efficacy of WBCT as an adjunctive treatment. This average decrease was significantly greater in the study group (Z= −3.722, p<0.001 and Z= −4.346, p<0.001, respectively). In the second week of treatment (T2–T3) there was again a significant decrease in depressive (Z= −4.160, p<0.001) and anxiety (Z= −4.379, p<0.001) symptoms within the study group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in anxiety and depressive scores within three weeks (mean, SD)

| Weeks of treatment | Study group (Δ mean) | Control group (Δ mean) | p-value for comparison of changes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamilton’s anxiety rating scale | 1(T1–T2) | −3.12 | −0.58 | <0.001 |

| 2(T2–T3) | −5.00 | −0.39 | <0.001 | |

| 3(T3–T4) | −2.77 | −0.83 | <0.05 | |

| Hamilton’s depression rating scale | 1(T1–T2) | −2.42 | +0.96 | <0.001 |

| 2(T2–T3) | −6.58 | −0.01 | <0.001 | |

| 3(T3–T4) | −2.00 | −0.22 | <0.05 |

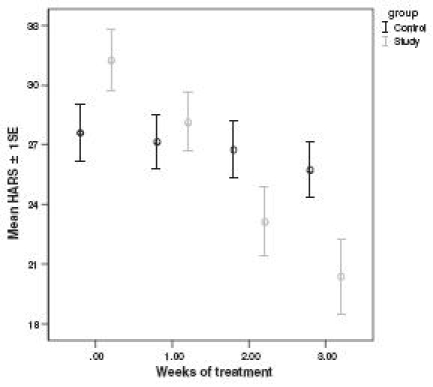

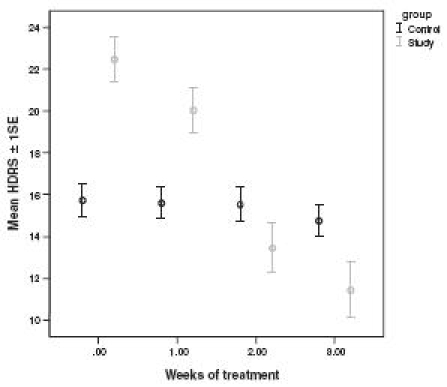

Considering the effects of treatment over the first two weeks, these decreases were significantly greater in the study group (Z= −6.218, p<0.001 and Z= −4.817, p<0.001, respectively). In the third week of treatment (T3–T4) a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms was observed in the control group (Z= −2.307, p<0.03). However, no such change was observed in the severity of depressive symptoms (Z= −0.081, p>0.9). In the study group a significant reduction was noted in both cases (Z= −2.995, p<0.004 and Z= −3.297, p<0.002, respectively). Again, these reductions were significantly greater in the study group (depression: Z= −4.295, p<0.001, anxiety: Z= -1.958, p=0.05). Over the first three weeks of treatment (T1–T4) a significant decrease was noted in the severity of anxiety (Fig. 1; control group: Z= −3.156, p<0.003, study group: Z= −4.436, p<0.001) and depression (control group: Z= −2.146, p<0.033, study group: Z= -4.461, p<0.001; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Intensity of anxiety symptoms within the measure points (HARS scores)

Fig. 2.

Intensity of depressive symptoms within the measure points (HDRS-17 scores).

Comparing the results from both groups (Table 2), over the first three weeks of treatment the reduction of symptoms was significantly greater in the study group (depression: Z= −6.306, p<0.001, anxiety: Z= −5.521, p<0.001). It should be stressed that significant decreases in both scores were observed in the study group during each week. Such reductions were only observed in the control group after three weeks. Also, the decrease in both scores was very significantly greater in the control group. A decrease of 50% from the baseline scores of depressive symptoms was noted in 34.6% (n=9) of the study group and only in 2.9% (n=1) of the control group (p<0.01, Fisher’s test). Such a reduction in anxiety symptoms was noted in 46.2% (n=12) of patients from the study group and none from the control group (p<0.001, Fisher’s test).

According to the regression model describing the level of anxiety symptoms, the type of treatment was the only factor associated with the rate of decrease of the anxiety score (3.88 units/week; |t|=5.52, p<0.001), whereas in the control group the rate of decrease was insignificant. Additionally, the association between the rate of decrease and the use of cryotherapy was the strongest association according to the model (it had the largest |t| value). According to the model describing the severity of depressive symptoms, only the type of treatment was associated with the rate at which the depression score decreased. In the study group the decrease rate was 4.15 units/week (|t|=8.83, p<0.001), whereas in the control group the decrease rate was insignificant. As in the model describing the anxiety score, the association between the decrease rate and the use of cryotherapy was the strongest.

The fact that the decrease rate of the scores in the control group was not significant may well be due to the fact that the decrease was not linear. This does not contradict the fact that there were significant decreases in these scores in the control group. However, the regression analysis does indicate that the decreases in these scores were significantly greater in the study group.

Discussion

The standard and most common method of biological treatment in psychiatry is currently the use of medications. However, a considerable percentage of patients do not respond positively and pharmacotherapy does not lead to remission. Research is being carried out into other, non-pharmacological strategies of treatment. Phototherapy was introduced at the beginning of the 1980s and has proved to be an effective method in treating the seasonally occurring mood disorder occurring in bipolar disorders. Electroconvulsive therapy is still in use. Other modern biological treatment methods are being developed. Methods involving neurostimulation include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, magnetic seizure therapy, vagus nerve stimulation, deep brain stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation. These methods may be effective in treating depression and have minimal side effects [4, 11, 13].

This study was aimed at investigating whether WBCT could be an effective aid to psychopharmaceutical treatment. No previous research has been carried out on the efficacy of cryotherapy in psychiatric treatment. The results suggest that cryotherapy may play a positive role in the process of treating patients with affective and anxiety disorders, since the decreases in the HARS and HDRS-17 scores were clearly greater in the study group than in the control group. A positive effect was already observable after one week of treatment and improvements continued to be significant over the whole three-week cycle of cryotherapy. A significant improvement, taken to be a decrease of at least 50% from the baseline severity of symptoms, was observed in almost half of the study group and only in one case in the control group. Analysis of the long-term observations will indicate whether this effect is long lasting. Even if the follow-up results indicate that the long-term effects of treatment are the same in both groups, the rapid initial improvement achieved using cryotherapy means that such adjunctive treatment may be of value.

The physiological mechanisms of WBCT mentioned in the Introduction, particularly those associated with the HPA axis and endogenous opioids, can be an explanation of the positive effect of WBCT on mood. Other unknown or unrecognized phenomena may be associated with the WBCT effect.

There is a possibility that WBCT only improves several symptoms among the many psychopathological phenomena associated with depressive or anxiety disorders. It can be suspected that WBCT provides pain relief and regulation of biological rhythms, which are common symptoms accompany emotional disorders; however, these hypotheses need to be confirmed in further studies.

Nevertheless, despite the positive results of the study, we are aware of its limitations. Among these one should mention the small sample size and the lack of a procedure randomly assigning patients to a group. We should also note the problem of recruiting patients to undergo a novel, unknown treatment requiring daily mobilization and adaptation to the rigors of a research program. Further studies are being planned involving such methods as neuro-imaging and biochemical measures with the aim of clarifying the effect of WBCT on mental health. There is ever-increasing interest in non-pharmacological strategies to treat depressive disorders. Several approaches are currently being investigated as novel forms of therapy and may well constitute new effective treatments for major depression.

Acknowledgments

The study was financed by a Wrocław Medical University research grant.

Abbreviations:

- WBCT

whole-body cryotherapy

- HDRS-17

Hamilton’s depression rating scale

- HARS

Hamilton’s anxiety rating scale

- ICD-10

international statistical classification of diseases and health related problems, tenth revision

References

- 1.Engel P., Fricke R., Taghawinejad M. and Hildebrandt G. (1989): Lungenfunktion und Ganzkörperkältebehandlung bei Patienten mit chronischer Polyarthritis. Z. Phys. Med. Baln. Med. Klim., 18 37–43.

- 2.Fricke R. (1989): Ganzkörperkältetherapie in einer Kältekammer mit Temperaturen um −110°C. Z. Phys. Med. Baln. Med. Klim., 18 1–10.

- 3.Gregorowicz H. and Zagrobelny Z. (2003): [Whole-body cryotherapy. Indications and contraindications, its course, and physiological and clinical results.] In Zagrobelny Z (ed.): [Local and whole-body cryotherapy]. Wydawnictwo Medyczne Urban & Partner, Wrocław, pp. 15–34.

- 4.Grunhaus L., Dannon P. N., Schreiber S., Dolberg O. H., Amiaz R., Ziv R. and Lefkifker E. (2000): Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is as effective as electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of nondelusional major depressive disorder: an open study. Biol. Psychiatry, 47, 314–324. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hamilton M. (1960): A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hamilton M. (1959): The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol., 32 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Korzonek-Szlacheta I., Wielkoszyński T., Stanek A., Swiętochowska E., Karpe J. and Sieroń A. (2007): [Influence of whole-body cryotherapy on the levels of some hormones in professional football players] Endokrynol. Pol., 58, 27–32. [PubMed]

- 8.Metzger D., Zwingmann C., Protz W. and Jackel W. H. (2000): Whole-body cryotherapy in rehabilitation of patients with rheumatoid diseases - pilot study. Rehabilitation, 39, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nestler E. J., Barrot M., DiLeone R. J., Eisch A. J., Gold S. J. and Monteggia L. M. (2002): Neurobiology of depression. Neuron, 34, 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Offenbacher M. and Stucki G. (2000): Physical therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Scand. J. Rheumatol. Suppl., 113 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rau A., Grossheinrich N., Palm U., Pogarell O. and Padberg F. (2007): Transcranial and deep brain stimulation approaches as treatment for depression. Clin. EEG Neurosci., 38 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Romuk E., Birkner E., Skrzep-Poloczek B., Jagodzinski L., Stanek A., Wisniowska B. and Sieron A. (2006): Effect of short time exposure of rats to extreme low temperature on some plasma and liver enzymes. Bull. Vet. Inst. Puławy, 50, 121–124.

- 13.Rush A. J., George M. S., Sackeim H. A., Marangell L. B., Husain M. M., Giller C., Nahas Z., Haines S., Simpson R. K. Jr. and Goodman R. (2000): Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol. Psychiatry, 47, 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Rymaszewska J., Biały D., Zagrobelny Z. and Kiejna A. (2000): The influence of wholebody cryotherapy on mental health. Psychiatr. Pol., 34 649–653. [PubMed]

- 15.Rymaszewska J., Tulczyński A., Zagrobelny Z. and Kiejna A. (2000): The influence of wholebody cryotherapy on mental health of the human. In Zagrobelny Z (ed.): Local and whole body cryotherapy. Wydawnictwo Medyczne Urban & Partner, Wrocńaw, pp. 177–185.

- 16.Rymaszewska J., Tulczyński A., Zagrobelny Z., Kiejna A. and Hadryś T. (2003): Influence of wholebody cryotherapy on depressive symptoms - preliminary report. Acta Neuropsychiatr., 15 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Samborski W., Stratz T., Sobieska M., Mennet M., Müller W. and Schulte-Mönting J. (1992) Intraindividueller Vergleich einer Ganzkörperkältetherapie und einer Wärmebehandlung mit Fangopackungen bei der generalisierten Tendomyopathie (GTM). Z. Rheumatol., 51 25–31. [PubMed]

- 18.Schroeder D. and Andersen M. (1995): Kryo- und Thermotherapie. Grundlangen und praktische Anwendung. Gustav Fisher Verlag, Stuttgart-Jena-New York.

- 19.Smolander J., Westerlund T., Uusitalo A., Dugué B., Oksa J. and Mikkelsson M. (2006): Lung function after acute and repeated exposures to extremely cold air (−110°C) during whole-body cryotherapy. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging, 26, 232–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Westerlund T., Oksa J., Smolander J. and Mikkelsson M. (2000): Thermal responses during and after whole-body cryotherapy (−110°C). J Thermal Biol., 28 601–608. [DOI]

- 21.Yamauchi T. (1989): Whole body cryo-therapy is method of extreme cold −175°C treatment initially used for rheumatoid arthritis. Z. Phys. Med. Baln. Med. Klim., 15 311.

- 22.Zagrobelny Z., Halawa B., Negrusz-Kawecka M., Spring A., Gregorowicz H., Wawrowska A. and Rozwadowski G. (1992): [Hormonal and hemodynamic changes caused by whole-body cooling in patients with rheumatoid arthritis]. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn., 87 34–40. [PubMed]

- 23.Zagrobelny Z (ed.) (2003): Local and whole body cryotherapy. Wydawnictwo Medyczne Urban & Partner, Wrocław. for the degree of Master of Science in Medicine.