Abstract

Motivation: The decision to commit some or many false positives in practice rests with the investigator. Unfortunately, not all error control procedures perform the same. Our problem is to choose an error control procedure to determine a P-value threshold for identifying differentially expressed pathways in high-throughput gene expression studies. Pathway analysis involves fewer tests than differential gene expression analysis, on the order of a few hundred. We discuss and compare methods for error control for pathway analysis with gene expression data.

Results: In consideration of the variability in test results, we find that the widely used Benjamini and Hochberg's (BH) false discovery rate (FDR) analysis is less robust than alternative procedures. BH's error control requires a large number of hypothesis tests, a reasonable assumption for differential gene expression analysis, though not the case with pathway-based analysis. Therefore, we advocate through a series of simulations and applications to real gene expression data that researchers control the number of false positives rather than the FDR.

Availability: Our R package, EPath.omg is available at http://sphhp.buffalo.edu/biostat/research/software.

Contact: dlgold@buffalo.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

DNA microarray technology makes possible the simultaneous monitoring of thousands of gene expression and has been widely applied to detect gene activity changes in many areas of biomedical research. Traditionally, the microarray data were analyzed using a gene by gene strategy, which focused on individual gene's expression change across contrasting conditions. This gene-based approach, while useful to identify the most significant changes, could often neglect the information in genes' joint distribution. From the viewpoint of biology, the biological mechanisms underlying gene activity change are generally the result of interactions between multiple genes in a modular pathway, with most of its members characterized by subtle active changes. Such modest but consistently coordinate effects are difficult to be identified by gene expression analysis.

To overcome the limitations of the gene expression analysis, pathway-based enrichment methods have been developed to identify changes in the collections of genes, thought to be involved in the same underlying biological process (i.e. pathway), thus allowing the incorporation and weighting of prior biological knowledge into microarray analysis. The earliest pathway-based approaches followed from Fisher's test, comparing the distributions counts of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each pathway with the overall distribution (Khatri and Drghici, 2005). Other methods include parametric analysis of gene set enrichment (PAGE) (Kim and Volsky, 2005), which attempts to model the changes in DEGs belonging to pathways by a parametric model. The more popular pathway analysis employ stringent permutation-based methods, attempting to account for gene–gene correlation. Examples of these are gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian, 2005) and gene set analysis (GSA) (Efron and Tibshirani, 2007). In GSEA, all of the genes are first ranked, by their significance in terms of differential expression, and then, the rankings are tested, to determine whether a particular predefined collection of genes is randomly distributed throughout the ranked list, or enriched at either the top or bottom of the list (Efron and Tibshirani, 2007; Subramanian, 2005). GSA employs the max–mean statistic, as a measure of significance for each pathway, what Efron and Tibshirani claim is more powerful and discriminatory approach, and uses a permutation-based approach to determine the null distribution.

One of the critical assumptions underlying the pathway-based strategy is the availability of a collection of well-curated pathways. These can be obtained through existing annotation information such as that provided by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000). KEGG is one of the most complete and academically available pathway databases, whose latest release includes about 210 curated non-redundant pathways in human. Although it is possible to create more gene sets in silico (e.g. through chromosome neighborhoods, expression neighborhoods and regulatory motif sharing, etc.), the increasing functional heterogeneity associated with such less-curated gene sets make them difficult for subsequent interpretation in terms of biological mechanism. As a result, many published pathway-based application (Jimeno et al., 2008; Pangas et al., 2008; Setlur et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007) or evaluation (Liu et al., 2007; Song and Black, 2008) in microarray data analysis used a couple of hundred well-curated non-redundant pathways merged from KEGG and other public annotation systems like Biocarta and/or Gene Ontology (GO). Although KEGG is not freely available to all users, our arguments regarding error control for pathway analysis apply to similar databases used to construct the pathways.

Both gene- and pathway-based analysis deal with the challenge of multiple testing error control (i.e. multiplicity correction ). Three universal error control strategies are applied in the microarray analysis literature, controlling the false discovery rate (FDR), false positive count or simply choosing the top K from a ranked list.

The FDR-based method of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) has been widely applied in the analysis of gene expression microarray analysis, and is also a popular choice in pathway-based microarray analysis. However, the size of multiplicity is quantitatively different between them. For example, the latest human U133plus 2.0 array contains ∼54 000 probe sets targeting at ∼38 000 human genes, including ∼37 000 probe sets for ∼18 000 curated refseq genes. On the other hand, typically much fewer than 500 canonical pathways (e.g. from KEGG, Biocarta or GO databases, etc.) are available for pathway-based approaches, and less are used after excluding pathways with less than a certain number of genes expressed in the chips. The shift from massive multiplicity in the gene expression approach, to reduced multiplicity in pathway-based methods raises interesting questions about the accuracy of FDR-based procedures in pathway studies. We addressed this issue here by first briefly reviewing the terminology of multiple testing.

1.1 Family-wise error rate

Suppose that 10 000 hypothesis tests are performed, each controlled at the 0.05 level. If all null hypotheses are true, on average you can expect 500 false positives, far too many false leads in practice. Carlo E. Bonferroni (1892–1960) suggested controlling the probability of at least one false positive, what he called the family-wise error rate (FWER). The FWER procedure, given N hypothesis tests, controls the FWER at level α with P-value threshold α/N. Notice that the Bonferroni threshold becomes more stringent, i.e. conservative, as the number of tests N increases, diminishing power for microarray analysis. For this reason new methods of error control were devised.

1.2 FDR analysis

Multiple statistical testing procedures began to be reexamined in the early 1990s, with the advent of high-throughput genomic technologies, in light of microarray analysis. Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) proposed controlling the FDR, or the expected rate of false test positives (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). In the BH multiple testing procedure, the FDR is controlled by the following scheme:

Let p(1) < ··· < p(N) denote the N ordered P-values.

Let

for the largest k such that p(k) ≤ α*k/N

for the largest k such that p(k) ≤ α*k/NReject all null hypothesis H0i for which

.

.

BH prove that if the above procedure is applied, then FDR ≤ α. Storey (2002) showed, for P-value threshold t,

| (1) |

where π is the probability that an alternative hypothesis is true, and F(t) is the distribution of P-values given the alternative. FDR performance has been evaluated for gene detection given a variety of scenarios, for examples, in the presence of gene–gene correlation (Benjamini and Yekutieli, 2001; Shao and Tseng, 2007). FDR analysis does not control what Genovese and Wasserman (2004) call the realized FDR (rFDR), the number of false rejections V divided by the number of rejections R (assuming at least one rejection), which in fact, can be quite variable, see our Supplementary Materials. Since researchers do not have knowledge of the truly DEGs, the rFDR is unknown in a real experiment. Several of the multiple testing procedures (MTPs) thus try to control the expectation of the rFDR, (often confusingly abbreviated as FDR).

BH control is achieved only in large sample sense, as BH showed that as the number of tests goes to infinity, the expected rate of false positives is bounded above. BH's result controls the FDR ≤(1 − π) α ≤ α as N → ∞, through π, the percentage of true (and in practice unknown) positives. In other words, a desired FDR control of 10% might yield less power than hoped for inversely to π (Storey, 2002).

1.3 Controlling the number of false positives

Lehman and Romano (2005) proposed controlling against at least K false positives, what he called K FWER (KFWER) with P-value threshold α · K/N. Like the FWER control, the KFWER P-value threshold becomes more stringent as the number of tests N becomes larger. We consider the K binomial method, KBIN (Miecznikowski et al., 2009), to control KFWER. Like Lehman and Romano (2005), KBIN also controls the probability of at least K false positives, although for our purposes can achieve greater power. The KBIN procedure follows from basic probability concepts, to control the probability that the number of false positives V is not larger than k to be α, that is,

where V is the number of false positives, assumed to follow a Binomial distribution, with k defined by the user. The procedure rejects all hypotheses with P-values less than αcut, where αcut is the value of α that solves the equation below

where F is the cumulative density function for a Binomial distribution with N trials and probability of success α and β is usually chosen to be large, e.g. 0.95. KFWER provides a convenient approximation for choosing αcut in the case that N is large.

In contrast, KBIN is determined before the data are observed, rather than estimated from data. Given the way the P-value threshold is estimated, when the number of false positives exceeds the desired bound K, it tends not to be much larger, see our Supplementary Materials. One might also consider selecting the top K pathways, i.e. with the smallest P-values. We call this method TopK. TopK and KBIN are less variable than BH for pathway analysis, although they have their own drawbacks such as lacking meaningful control and interpretation. For example, suppose for KBIN K = 5, and three pathways are discovered, while in another case 20 pathways are discovered. Clearly the latter seems to lend better interpretation. In practice, it is impossible to predict how many pathways will be detected with KBIN.

2 METHODS

2.1 Simulation studies

The theoretical results of BH's FDR control hinge on a large number of tests. This begs the question, when is it inappropriate to report α-control of FDR? In order to answer this question, we illustrate the performance of BH's FDR analysis simulating data under two scenarios. In Simulation 1, we have a relatively large number of significant tests, each with small effects. In Simulation 2, there are fewer relative significant tests, but when significant, the effects are larger. The underlying P-value distributions in our simulations are described at length in the Appendix A. In both simulations, we let the number of tests N = 250. Simulating from a model provides us with well-defined functions, FDR(t) and rFDR(t), of the P-value threshold t.

We compare the discrimination performance of our candidates: BH, KBIN and TopK, for Simulations 1 and 2, each of the 10 000 iterations. The true positive detection rate (PDR) and the true negative detection rate (NDR) were measured in each simulation as the mean number of positives and negatives, detected at a given threshold. While it is not possible to compare BH, KBIN and TopK directly since they control different quantities, there exists, for example, a pair (α,K) yielding near identical average PDR performance for both BH and KBIN. Therefore, we consider a range of criteria: for FDR, we let α ranged from 0.01 to 0.99, KBIN K ranges from 0 to 250 and TopK, K ranges from 1 to 250. We use 20 and 50 values for each method in either simulation, respectively. We compare both the relative PDR/NDR mean and standard deviation (SD) by method across all 10 000 simulated datasets.

2.2 Gene expression data

We perform pathway analysis on a subset of the samples in the cervical cancer study of Scotto et al. (2008), contrasting pathways in normal (24 cases) from cervical cancer (33 cases) specimens, on U133A Affymetrix arrays. Unlike simulated data, real data pathway analysis can be influenced by gene–gene correlation. To this end we favor permutation-based methods that attempt to account for gene–gene correlation yielding more robust results. PAGE and expression analysis systematic explorer (EASE), for example, ignore gene–gene correlation in determining P-values (Hosack et al., 2003; Kim and Volsky, 2005).

We compare the performance of KBIN and BH, for various levels of control, given the nominal P-values of GSA (Efron and Tibshirani, 2007) and GSEA (Subramanian, 2005). We modified the original restandardization step in GSA, rescaling by the max–mean scores by the median absolute deviation (MAD). The MAD estimator is more robust to outliers, i.e. significant max–mean statistics and thus yields nominal P-value distributions more consistent with the underlying assumptions of BH. In the authors' experience, an abundance of positive, or negative, max–mean scores, can inflate the SD estimate for restandardization, and potentially bias the nominal P-value distribution. This issue is easily rectified with the more robust MAD estimator. Otherwise, we did not alter GSA, nor seek improvements or modifications. For GSEA, we perform the kolmogorov-smirnov (KS) test, i.e. setting P = 0 in the original algorithm, and applied BH and KBIN to the nominal P-values (i.e. we did not apply GSEA's multiple testing procedure, which we comment on below). We repeat analysis on 100 boot strapped versions of the data (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994), to contrast the distributions on the results, in particular the (random) number of pathways discovered as enriched for each criterion and method. We repeated the above analysis comparing gene expression in smokers versus non-smokers, from the Spira et al. study, on U133A Affymetrix arrays Spira et al. (2004), and differences in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) with and without down syndrome status (Bourquin et al., 2006).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Simulation studies

3.1.1 FDR and rFDR

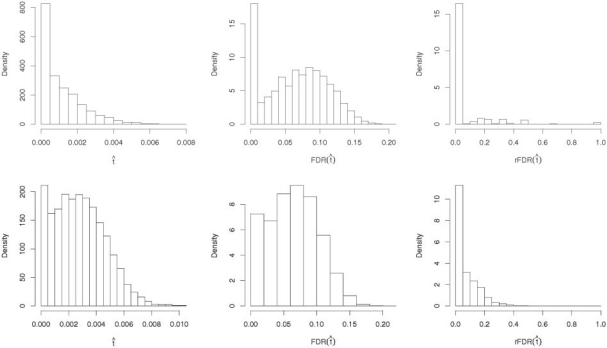

There is a discordance between the FDR and rFDR for pathway analysis. In Figure 1, the variability in the rFDR for both Simulations 1 and 2 is extreme, and appears to be quite discordant from the FDR control level. Researchers should find this troubling. The frequency histogram of  , shows the sampling variability in the decision rule to reject. This variability can better be illustrated though the FDR function, as function of

, shows the sampling variability in the decision rule to reject. This variability can better be illustrated though the FDR function, as function of  , not to be confused with the desired FDR level of control level which is a constant. In the results of Simulation 1, there is a spike in the probability that the

, not to be confused with the desired FDR level of control level which is a constant. In the results of Simulation 1, there is a spike in the probability that the  , and a long right tail. Similar results are observed for Simulation 2. This indicates that the method has a tendency to be overly conservative for N = 250 tests. Summary statistics for each simulation are listed in Table 1 of Supplementary Materials, including results for BH control at α = 0.01. Note that for N = 5000, available in the Supplementary Materials, the discordance between FDR and rFDR disappears.

, and a long right tail. Similar results are observed for Simulation 2. This indicates that the method has a tendency to be overly conservative for N = 250 tests. Summary statistics for each simulation are listed in Table 1 of Supplementary Materials, including results for BH control at α = 0.01. Note that for N = 5000, available in the Supplementary Materials, the discordance between FDR and rFDR disappears.

Fig. 1.

Simulation of sampling variability in FDR and rFDR top row Simulation 1, bottom row Simulation 2, for FDR control level of 10%.

Table 1.

Mean and SD of counts of cervical cancer pathways detected

|

GSA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 6.8 | 8.48 | 10.26 | 11.56 | 13.26 | 14.72 | 16.53 |

| SD | 2.4 | 3.27 | 3.29 | 3.38 | 3.33 | 3.76 | 4.22 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 6.8 | 9.85 | 10.83 | 12.27 | 13.91 | 15.95 | 16.57 |

| SD | 2.4 | 2.59 | 2.49 | 2.4 | 2.35 | 2.55 | 2.61 | |

|

GSEA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 3.73 | 4.19 | 5.67 | 7.09 | 8.74 | 10.64 | 12.21 |

| SD | 1.57 | 2.29 | 2.7 | 3.45 | 4.34 | 5.41 | 6.17 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 3.73 | 6.27 | 7.11 | 8.86 | 11.12 | 13.94 | 14.65 |

| SD | 1.57 | 2.18 | 2.5 | 2.78 | 3.08 | 3.44 | 3.54 | |

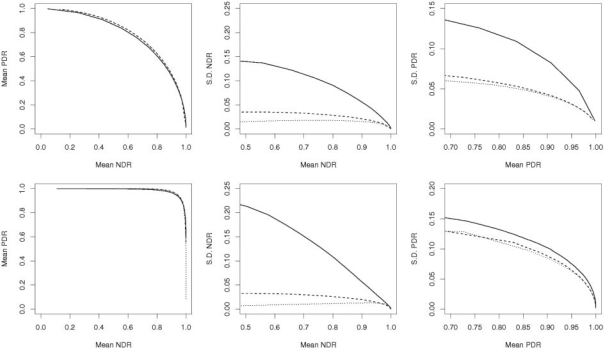

3.1.2 Comparison of error control procedures

A method that can achieve, say, on average higher PDR than all other methods, over the range of NDR, would be attractive, although variability can play a role. In Figure 2, average PDR, over 10 000 simulations, improves as the threshold becomes more liberal, i.e. leading to negative consequences for the average NDR. Notice, the relative performance of all three methods is on average the same, yet the SD in PDR and NDR, measured over all 10 000 simulated datasets, tends to be higher for BH than KBIN and TopK. The trend in the SD falls as the average PDR or NDR improve, expected since at P-value threshold extremes there are fewer relative misclassifications, respectively. Practically speaking, this means that KBIN and TopK provide typically less variable results than BH, while delivering the overall expected benefit of error control.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of BH (solid), KBIN (dash) and TopK (dot): top row Simulation 1, bottom row Simulation 2.

3.2 Application to real data

Since BH and KBIN control different things, the two are not directly comparable. Hence, for a multitude of control levels, we use the mean number of pathways detected, estimated by bootstrap analysis, as the equating metric between BH and KBIN. This allows sufficient comparison of the bootstrap variability in the number of pathways detected, for different control levels between procedures, that on average yield similar results. For any level of control, the method that is most consistent is preferred. Below we list selected results for each dataset, see our Supplementary Materials for complete results.

3.2.1 Cervical cancer

We found similar results in BH and KBIN for conservative control, the relative variability in BH increased as the control was allowed to be more liberal. For example, BH's with 1% FDR control and KBIN with K = 1 yield mean (SD) counts of discovered pathways across bootstrap versions of the dataset of 6.8 (2.4). For GSA and GSEA, respectively, BH controlled at the 10% FDR level, yields mean (SD) counts of 10.26 (3.29) and 5.79 (2.6), and KBIN with K = 2 yields 9.85 (2.59) and 6.36 (2.11). The mean (SD) of counts for FDR control at 20% are 13.26 (3.33) and 8.77 (4.24), while KBIN with K = 6 yields 13.91 (2.35) and 8.88 (2.69), see Table 1.

3.2.2 Smoking-associated changes in gene expression

In this dataset, similar to what we found in the Cervical cancer data, we noticed that GSA tended to yield more pathways than GSEA. Given the results of GSA, BH controlled at 10% and 20% FDR yields mean (SD) counts of 5.41 (4.19) and 7.41 (5.6) discovered pathways. In contrast, KBIN with K = 2 yields 5.11 (3.18) and K = 3, 7.15 (3.95) counts, respectively. Given the P-values from GSEA, FDR control of 20% yields 1.65 (3.03) counts compared with KBIN with K = 2 of 1.44 (1.62) counts, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean and SD of counts of smoking-related pathways detected

|

GSA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 3.75 | 4.28 | 5.41 | 5.41 | 7.41 | 9.08 | 10 |

| SD | 2.45 | 3.29 | 4.19 | 4.19 | 5.6 | 6.57 | 7.22 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 3.75 | 5.11 | 7.15 | 7.95 | 10.01 | 11.72 | 12.64 |

| SD | 2.45 | 3.18 | 3.95 | 4.19 | 4.82 | 5.19 | 5.32 | |

|

GSEA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 1.33 | 1.65 | 2.8 | 3.27 |

| SD | 1.12 | 1.36 | 1.68 | 2.07 | 3.03 | 4.23 | 4.68 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 0.82 | 1.44 | 3.04 | 3.59 | 5.74 | 7.55 | 8.79 |

| SD | 1.12 | 1.62 | 2.31 | 2.32 | 3.26 | 3.8 | 4.05 | |

3.2.3 Down Syndrome-associated changes in AMKL

As shown in Table 3, KBIN shows >4-fold less variability than BH in this dataset, for on average comparable results. Fewer pathways were detected with BH, for both GSA and GSEA, over a range of control levels, than KBIN. Controlling at 35% FDR, the mean count of detected pathways is 1.06 (2.47) and 1.15 (2.29), respectively. KBIN, K = 2, yields a mean count of 1.02 (1.14) pathways for GSA and 1.25 (1.14) pathways for GSEA.

Table 3.

Mean and SD of counts of AMKL pathways detected

|

GSA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| SD | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.79 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 0.28 | 1.02 | 1.43 | 2.26 | 3.33 | 5.1 | 5.41 |

| SD | 0.6 | 1.14 | 1.38 | 1.81 | 2.26 | 2.88 | 3.03 | |

|

GSEA | ||||||||

| α | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| BH | Mean | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.84 | |

| K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| KBIN | Mean | 0.33 | 1.25 | 1.64 | 2.51 | 3.72 | 5.2 | 5.62 |

| SD | 0.65 | 1.14 | 1.37 | 1.67 | 2.14 | 2.54 | 2.6 | |

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

While there are now many methods for conducting pathway analysis (Huang et al., 2008), relatively little is discussed about how to control the error for pathway discovery. We recognize that in practice, a variety and/or composite of error control methods are applied. For our purposes, we were concerned with comparing the sole performance of representative methods including BH, KBIN and TopK. BH is widely applied, partly because it requires less computation than competing FDR analysis, offering a simple interpretation, i.e. FDR ≤ α. In contrast, KBIN bounds the probability of committing more than a specified number of false positives. While KFWER and KBIN offer control of the false positive count, KBIN is more powerful and, thus preferred. Our results demonstrate the sole performance of individual method, which serves for future study of consensus approaches.

We found BH more variable than KBIN or TopK for pathway analysis, both in simulation and with three real datasets, from independent labs, addressing different hypotheses. The reason for the variability in BH's FDR analysis is that  is estimated from data, and therefore suffers from sampling variation. Note, when the number of tests is much greater than N = 250 tests, say N ≥ 5000, the variability in the sampling distribution of the rFDR is considerably reduced, see Supplementary Materials.FDR control procedures, that attempt to estimate the distribution of the p-values will suffer from sampling variability as we demonstrated.

is estimated from data, and therefore suffers from sampling variation. Note, when the number of tests is much greater than N = 250 tests, say N ≥ 5000, the variability in the sampling distribution of the rFDR is considerably reduced, see Supplementary Materials.FDR control procedures, that attempt to estimate the distribution of the p-values will suffer from sampling variability as we demonstrated.

If one expects to obtain, for example, a list of 10–20 candidate pathways, a liberal FDR control of 30% provides reasonable costs. In our applications, KBIN yields, with comparable results to that of BH's FDR control of 30%, between a 2.25- and 4-fold reduction in variability in the count of detected pathways across three bootstrap analysis of independent datasets. While BH's error control procedure offers interpretation for gene discovery, interpretation is lacking for pathways, due to the variability in the rFDR. We prefer KBIN for pathway analysis, yielding less variability than BH, and better interpretation than TopK.

We encourage investigators to consider the relative costs in selecting an error control procedure, taking into account N, the number of hypothesis tests. Gene annotations will no doubt evolve, eventually calling for new methods for pathway analysis. Procedures that attempt to control error should be examined in the light of what they are controlling and how accurately they control it given what is known about the experiments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was performed in part at the University at Buffalos Center for Computational Research.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

A APPENDIX

A1 Simulations: two-component mixture model

A useful and widely adopted model considered for FDR analysis is the two-component P-value mixture model, pi ∼ (1 − π)u + π f, for i = 1,…, N pathways. The first component of the mixture follows a uniform distribution, the distribution of P-values when the null is true. The second component f is assumed to be concave. The mixture weight π, the percentage of pathways that are enriched, is generally assumed to be small. For any P-value threshold t, the FDR(t) = (1 − π)t/((1 − π)t + π F(t)) for cumulative distribution function of the P-values for which the alternative is true, F(t) = ∫t0 f(t)dt. The realized FDR, the rate of false positives (FPs), rather than expected rate, follows the distribution of η1/(η1 + η2), if η1 + η2 > 0, for η1 ∼ Binomial(N, (1 − π)t) and η2 ∼ Binomial(N, π F(t)), i.e. distributed as Binomial random variables with N trials and respective success probabilities. Otherwise, the rFDR is equal to zero if no discoveries are made. This is a complicated distribution, often easier to simulate than determine analytically.

In the first simulation, we let N = 250, π = 0.20 and the distribution of P-values under the alternative hypothesis, i.e. for enriched pathways, follows a beta distribution with parameters 1/2 and 2. This simulation corresponds to the case where many pathways are enriched, although, the differential effects in gene expression underlying enrichment are moderate. Since the true FDR function is known, we find that FDR (0.001734105) = 10%. In our second simulation, we let π = 0.05, and the distribution of P-values for enriched pathways follows a beta distribution with parameters 0.1 and 10, corresponding to the situation of few enriched pathways, with large effect sizes in differential gene expression underlying the enrichment. In this case, we find that FDR (0.004468064)=10%.

REFERENCES

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Bourquin J, et al. Identification of distinct molecular phenotypes in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3339–3344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511150103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Vol. 1. Boca Raton FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. On testing the significance of sets of genes. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2007;1:107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese C, Wasserman L. A stochastic approach to false discovery control. Ann. Stat. 2004;32:1035–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Hosack D, et al. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with ease. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, et al. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimeno A, et al. Coordinated epidermal growth factor receptor pathway gene overexpression predicts epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor sensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2841–2849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P, Drghici S. Ontological analysis of gene expression data: current tools, limitations, and open problems. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3587–3595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Volsky D. PAGE: parametric analysis of gene set enrichment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman E, Romano J. Generalizations of the familywise error rate. Ann. Stat. 2005;23:1138–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, et al. Comparative evaluation of gene-set analysis methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miecznikowski J, et al. KBIN: A method to control the number of false positives. Technical Report No. 0905. 2009 Available at http://sphhp.buffalo.edu/biostat/research/techreports/index.php. [Google Scholar]

- Pangas S, et al. Conditional deletion of Smad1 and Smad5 in somatic cells of male and female gonads leads to metastatic tumor development in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:248–257. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01404-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotto L, et al. Identification of copy number gain and overexpressed genes on chromosome arm 20q by an integrative genomic approach in cervical cancer: potential role in progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:755–765. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlur S, et al. Integrative microarray analysis of pathways dysregulated in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10296–10303. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Tseng C-H. Sample size calculation with dependence adjustment for FDR-control in microarray studies. Stat. Med. 2007;26:4219–4237. doi: 10.1002/sim.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Black M. Microarray-based gene set analysis: a comparison of current methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:502. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira A, et al. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10143–10148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401422101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, et al. A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, et al. Identification of prostate cancer modifier pathways using parental strain expression mapping. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17771–17776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708476104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.