Abstract

Motivation: High-resolution copy-number (CN) analysis has in recent years gained much attention, not only for the purpose of identifying CN aberrations associated with a certain phenotype, but also for identifying CN polymorphisms. In order for such studies to be successful and cost effective, the statistical methods have to be optimized. We propose a single-array preprocessing method for estimating full-resolution total CNs. It is applicable to all Affymetrix genotyping arrays, including the recent ones that also contain non-polymorphic probes. A reference signal is only needed at the last step when calculating relative CNs.

Results: As with our method for earlier generations of arrays, this one controls for allelic crosstalk, probe affinities and PCR fragment-length effects. Additionally, it also corrects for probe sequence effects and co-hybridization of fragments digested by multiple enzymes that takes place on the latest chips. We compare our method with Affymetrix's CN5 method and the dChip method by assessing how well they differentiate between various CN states at the full resolution and various amounts of smoothing. Although CRMA v2 is a single-array method, we observe that it performs as well as or better than alternative methods that use data from all arrays for their preprocessing. This shows that it is possible to do online analysis in large-scale projects where additional arrays are introduced over time.

Availability: A bounded-memory implementation that can process any number of arrays is available in the open source R package aroma.affymetrix.

Contact: hb@stat.berkeley.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Following the suite of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays (‘10K’, ‘100K’ and ‘500K’), Affymetrix has released a new class of chip types referred to as GenomeWideSNP (GWS), which in addition to SNP units include non-polymorphic probes, also called copy-number (CN) probes. The latter can be used to estimate the amount of target DNA at loci other than SNPs. The GenomeWideSNP_5 (GWS5), released February 2007, is targeted by Affymetrix as a genotyping assay, whereas the GenomeWideSNP_6 (GWS6), released May 2007, is targeted as both a genotyping and a CN assay.

In this article, we present the CRMA v2 method for estimating full-resolution raw total CNs. It extends and improves upon CRMA (Bengtsson et al., 2008b) and applies to all Affymetrix genotyping arrays including GWS and custom arrays. Likewise, it does not require genotype calls. The main objective of this method is to estimate full-resolution CNs so that segmentation and other downstream analyses can discriminate better between any two CN states.

In contrast to several other methods, CRMA v2 is a single-array method that processes each array independently of the others. In order to achieve this, we had to overcome the challenges in adapting CRMA's multi-array steps. Access to a single-array preprocessing method has several implications: (i) Only two hybridizations are required for paired analysis, e.g. in a single-person tumor-normal study, which is further illustrated by the results in Section 3.2. (ii) Each array can be preprocessed immediately after being scanned. (iii) Arrays can be processed in parallel on different hosts/processors making it possible to decrease the processing time of a set of arrays linearly with the number of processors. (iv) There is no need to reprocess an array when new arrays are produced, which further saves time and computational resources. Furthermore, (v) the decision to filter out poor arrays can be made later, because a poor array will not affect the preprocessing of other arrays. More importantly, a single-array method is (vi) potentially very practical for applied medical diagnostics, because individual patients can be analyzed at once, even when they come singly rather than in batches.

The outline of this article is as follows. In Section 2, we start by describing important differences between the new GWS arrays and the earlier SNP arrays. In light of this, we explain how the original CRMA (v1) model is adapted for GWS, and how it is further enhanced by introducing a normalization step controlling for probe sequence effects. Each step is modified so that it can be applied to an array independently of the others. At the end of this section, the evaluation method used for comparing with existing methods is described. In Section 3, we compare the different methods based on their performances at different levels of resolution and stratified by SNP or CN loci. In Section 4, we conclude the study and give future research directions.

2 METHODS

2.1 Overview of the GWS arrays

The GWS6 chip type interrogates 931 946 SNPs and 945 826 CN loci totaling 1 877 772 loci, whereas GWS5 interrogates 500 568 SNPs and 417 269 CN loci totaling 917 837 unique loci. GWS5 has the same set of SNPs as the 500K chip set, whereas for GWS6 6238 of those have been replaced by a new set of 437 616 SNPs. Among CN loci, only 61 846 are identical on GWS5 and GWS6. In contrast to previous generations of chip types, there are no mismatches but only perfect-match (PM) probes. On GWS5, all SNPs have four replicated (PMA, PMB) pairs. On GWS6 there are either three or four such pairs. These probe pairs are identical replicates, whereas before they were slightly shifted relative to the SNP position. For both GWS arrays, the pairs in each SNP were selected so that they optimized the genotype performance. For the GWS5, there was no constraint that the PMA and PMB sequences had to be aligned on the genome, causing 192 399 (38.4%) SNPs to have misaligned PMA and PMB. There was also no constraint that PMA and PMB should be on the same strand, resulting in 46 176 (9.22%) SNPs with PMA and PMB on opposite strands. These constraints were reintroduced for GWS6. The above GWS annotation is summarized in Table 1. More details on the GWS arrays are available in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Summary of the annotation available in the (‘full’) GWS CDFs

| GWS5 | GWS6 | |

|---|---|---|

| Unit types | ||

| SNPs | 500 568 | 931 946 |

| CN units | 417 269 | 945 826 |

| Total | 917 847 | 1 877 772 |

| SNP probe pairs | ||

| SNPs with three pairs | 0 | 811 179 |

| SNPs with four pairs | 500 568 | 120 767 |

| SNP alignment | ||

| Aligned allele pairs | 308 169 | 931 946 |

| Non-aligned allele pairs | 192 399 | 0 |

| SNP strandness | ||

| Sense only | 260 266 | 491 830 |

| Antisense only | 194 126 | 440 116 |

| Opposite strands | 46 176 | 0 |

| Both strands | 0 | 0 |

For the 100K as well as the 500K SNP-only assays, DNA is prepared in two parallel processes, each digesting the DNA using a unique enzyme, amplifying the fragments by PCR, and hybridizing the products to separate arrays. In the GWS assays, which like 500K, uses the enzymes NspI and StyI, the two mixes of PCR products are no longer hybridized to separate arrays but instead to the same array (Affymetrix Inc., 2007a, b). Consequently, some of the SNP target DNA of PCR products originating from different restriction digestions (enzymes) will hybridize to the same probe. The non-polymorphic (CN) probes were designed to target DNA either from both enzymes or NspI exclusively, but not from StyI alone. For an explanation of this and a summary of how many SNP and CN loci are targeted by the two enzymes, see the Supplementary Material.

Finally, for GWS5 and GWS6, Affymetrix has identified 59 744 (6.51% of all loci) and 25 346 (1.35%) SNPs, respectively, that do not meet their quality criteria (S.Cawley, Affymetrix, private communication). In order to differentiate between the filtered and non-filtered sets of loci, Affymetrix provides one ‘default’ chip definition file (CDF) and one ‘full’ CDF. Further details on the two types of CDFs are given in the Supplementary Material.

2.2 Proposed model

The CRMA v2 method takes an approach similar to CRMA v1 for estimating total (non-polymorphic) CNs. The model for allelic-crosstalk calibration is adapted to GWS, because of the added non-polymorphic probes. After this calibration, we utilize a nucleotide-position model not only to normalize for small difference across arrays but also for allelic imbalances in PMA and PMB. In contrast to our previous multi-array model, we here use a single-array model to summarize the probes. At the end, PCR fragment-length normalization is updated to model the multi-enzyme hybridization.

CRMA v2 was designed to be: (i) backward compatible with previous generations of arrays; (ii) prepared (as far as possible) for future generations of arrays; (iii) sequential, so that it is easy to replace or add other steps; and (iv) such that each array can be processed independently of the others. The latter allows for online single-array CN analysis, which is useful not only in projects with a very small or a very large number of arrays, but also in projects where arrays are generated over an extended period of time. It is only in the last step while calculating relative CNs that a reference is needed. Although not discussed further in this article, we also look toward a unified method for estimating allele-specific CNs.

2.2.1 Calibration for offset and crosstalk between alleles

For reasons explained in Bengtsson et al. (2008b), the (PMA,PMB) signals are affected by allelic crosstalk. It was shown that correcting for crosstalk as well as offset significantly improved the ability to differentiate between CN states. The offset & crosstalk model introduced in CRMA v1 needs to be modified for GWS arrays in order to control for offset in the new non-polymorphic probes. For SNPs, let xijk = (xijkA, xijkB) and yijk=(yijkA, yijkB) denote the true and the observed signals for probe pair (j, k) in SNP j, probe k=1,…, Kj, and sample i = 1,…, I. Without loss of generality, assume that probes in each pair are ordered lexicographically by the SNP nucleotides (nts), resulting in six possible pairs. For a particular pair, we model the allelic crosstalk and shift observed in {yijk} by an array-specific affine transformation as

| (1) |

where ai=(aiA, aiB)T denotes the offset,

| (2) |

is the crosstalk matrix, and εijk=(εijkA, εijkB)T is noise. In order to avoid biases in parameter estimates due to aberrant CNs, this model is fitted based on signals from autosomal chromosomes only, or more generally to a subset 𝒥* of loci that are likely to be copy neutral regardless of sample, i.e. signals from ChrX and ChrY as well as known CN polymorphic regions are excluded. If some of the remaining loci are not copy neutral, we rely on robustness of the estimator to get unbiased estimates. Estimates of the true signals are obtained by backtransforming as

| (3) |

In words, the crosstalk correction for SNPs is performed by treating the data as points sampled from a polyhedral cone in multidimensional space. The apex (ai) of the cone is the baseline intensity for all channels, and edges (defined by Si) are directions corresponding to pure signals. Zeroing the apex and orthogonalizing the edges remove the baseline and the crosstalk. The cone is fitted iteratively by minimizing the distance from the cone to the points that lie outside it (Wirapati and Speed, 2002). For other non-SNP probes, including CN probes, we estimate and correct for the offset as the weighted average of offsets across all 6 nt pairs with weights inversely proportional to the number of data points in each group. The reason for calculating the offset this way is the belief that there is a dominant offset that is shared by all probes, e.g. scanner offsets (Bengtsson et al., 2004), a view which is strengthened by our parallel studies on Affymetrix resequencing arrays. This would also suggest that the offsets in Equation (1) should be symmetric in the two alleles and same for all six pairs, but for practical reasons (Bengtsson et al., 2008b) we do not do this.

Another difference from CRMA v1 is that after correcting for offset, rescaling to the same arbitrary average (=2200) is based on the median of all probes pooled together, instead of separately for each nucleotide pair. This is done to prevent systematic biases between SNP and CN loci due to enzymatic mixture imbalances.

As in CRMA v1, the above crosstalk calibration method is applied to each array independently. Despite this, it still controls for gross differences across arrays (Bengtsson et al., 2008b). In addition to the fact that the crosstalk of the underlying signals has affine properties, in practice it is the possibility of rescaling toward a common arbitrary average (instead of, say, an average across all arrays) that makes this a single-array step.

2.2.2 Normalization for probe sequence effects

It has been shown that the affinity of a probe can be attributed to its sequence composition (Binder et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2007; Naef and Magnasco, 2003; Wu et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2007). As in Carvalho et al. (2007), we model the probe sequence affinity as a function of nucleotide and position in order to control for (i) small fluctuations in probe affinities across arrays, and (ii) differences in PMA and PMB affinities. Consider all probes k′=1,…, K′ on the array and let bk′ = (bk′,1, bk′,2,…, bk′,25) be the probe sequence for probe k′ with nucleotide bk′,t∈{A, C, G, T} at position t=1,…, 25. According to the probe-position model (Carvalho et al., 2007), the crosstalk and offset calibrated signals  for probe k′ of a given array i=1,…, I, can be described (on the intensity scale) by:

for probe k′ of a given array i=1,…, I, can be described (on the intensity scale) by:

| (4) |

where μik′ is the probe signal of interest, ρik′ > 0 is the array- and sequence-specific affinity, and ξik′ is noise. The affinities are modeled on the logarithmic scale as:

| (5) |

where {hib(·)}b are nucleotide-specific smooth functions and 𝕀(·) is the indicator function. The model is constrained such that ∑b∈{A,C,G,T} hib(t) = 0 at each position t. We choose to model {hib(·)}b with cubic splines with 5 degrees of freedom (d.f.) (we get very similar results for 7 and 9 d.f.). The model is fitted on the logarithmic scale with non-positive signals excluded, and as before, only to the subset of probes that are expected to be copy neutral. Given estimates {ĥib(·)}b, all probe signals can be normalized as:

| (6) |

where  denotes the offset and crosstalk calibrated and probe-sequence normalized signals. As in Carvalho et al. (2007), we observe small systematic effects across arrays {hib(·)}b, which introduce extra variance. In addition, the difference in affinity between PMB and PMA is hibB(t)−hibA(t), where t is the SNP probe position. If not controlled for, it will bias heterozygote signals (AB) relative to homozygote signals (AA or BB), when calculating the total signals. We note that the latter effect can be controlled for by introducing a heterozygote component in the crosstalk model, but as argued in Bengtsson et al. (2008b) such an approach is likely to be sensitive to model errors, e.g. when there are a lot of CN aberrations which may be the case for some tumors.

denotes the offset and crosstalk calibrated and probe-sequence normalized signals. As in Carvalho et al. (2007), we observe small systematic effects across arrays {hib(·)}b, which introduce extra variance. In addition, the difference in affinity between PMB and PMA is hibB(t)−hibA(t), where t is the SNP probe position. If not controlled for, it will bias heterozygote signals (AB) relative to homozygote signals (AA or BB), when calculating the total signals. We note that the latter effect can be controlled for by introducing a heterozygote component in the crosstalk model, but as argued in Bengtsson et al. (2008b) such an approach is likely to be sensitive to model errors, e.g. when there are a lot of CN aberrations which may be the case for some tumors.

The above method is by design a single-array normalization method. An alternative, multi-array method, is to replace the correction factor in Equation (6) with  , where ρRk′ is calculated as the average effect across arrays. This would result in smaller adjustments per array while still normalizing across arrays. However, because of the overall (affine) design of CRMA v2, such terms (ρRk′) cancel out when calculating relative CNs.

, where ρRk′ is calculated as the average effect across arrays. This would result in smaller adjustments per array while still normalizing across arrays. However, because of the overall (affine) design of CRMA v2, such terms (ρRk′) cancel out when calculating relative CNs.

2.2.3 Probe-level summarization

With technically replicated probes, as in the most recent chip types GWS5 and GWS6, and assuming that the effect from neighboring probes is negligible, probe affinities used in multi-array summarization models will vanish. For these reasons, we consider the following single-array summarization estimates for total CNs:

| (7) |

where the median is calculated across all probe-pair sums k=1,…, Kj in SNP j. For older chip types (10–500K) for which the replicated probes are slightly shifted along the genome, it is still sensible to model the probe affinities using a multi-array model such as the log-additive model used in CRMA v1. Since these chip types are considered outdated, we have not conducted a formal study comparing the two summarization models, but from our experience we do note a small gain when using the log-additive model (no such gain is observed for GWS6). Thus, for these arrays, the choice will be a trade-off of receiving this gain and having the option to process each array independently of the others.

Finally, for non-polymorphic loci, which are all single-probe units (as defined by the CDFs used here), we let

| (8) |

be the corresponding estimates for unit/probe j in sample i. If in future chip types, or related custom genotyping arrays, there are replicated non-polymorphic probes, Equation (8) should be replaced by summaries as in Equation (7).

2.2.4 Normalization for fragment-length effects

Because fragments from two enzymes are hybridized to the same array for GWS, some probes will match fragments originating from both restriction digestions. See the Supplementary Material for details on how many SNP and CN loci are exclusively on NspI, StyI and on both. For signals originating from only one of the digestions, we could, for each enzyme separately, apply the fragment-length normalization method proposed in Bengtsson et al. (2008b). However, because a signal that originates from both digestions consists of one NspI and one StyI component, which each has been amplified differently, another method has to be used for such units. For this reason, we modify our previous model as described next.

First, assume that the number of fragments obtained from digesting with a particular enzyme is independent of locus j. This assumption was implicit in CRMA v1. Continuing, let λrj be the length of the fragment that was digested by restriction enzyme r∈{Nsp, Sty} and contains locus j. For sample i=1,…,I, assume that the amount of PCR amplification of a fragment from digestion with enzyme r∈{Nsp, Sty} is proportional to 2hri(λrj), where hri(·) is a sample-specific smooth function on the logarithmic scale. Next, labeled PCR products of the two digestions are mixed together. Let ρri>0 be the total amount of product for enzyme r in sample i relative to the Nsp I enzyme, such that ρNspi = 1 for all samples. Furthermore, assume that the amount of target hybridized to a specific probe is proportional to the number of labeled sequences. When targets from more than one digestion (enzyme) hybridize to the same probe, assume there is no preference for either enzyme. Next, let κi > 0 be the overall efficiency of hybridization, scanning, image analysis, etc., for array i relative to the first array, such that κ1 = 1. Finally, define gri(·) such that 2gri(λrj) = κiρri2hri(λrj) describes, as a scale factor, the overall systematic effect for locus j in sample i due to fragmentation, PCR amplification, mixing, hybridization and so on. To conclude, for a probe interrogating sequences from both digestions, we assume that the signal for sample i at locus j is proportional to:

| (9) |

We say that the confounded fragment-length effect is additive on the intensity scale. With this model, each fragment-length effect {gir(·)}r can be estimated from signals exclusively from a single digestion.

In Bengtsson et al. (2008b), we normalized the data toward target fragment-length effects estimated as the average effects across arrays. In the effort to avoid multi-array estimators in CRMA v2, we here normalize data toward fixed target effects. The choice of target functions is not important because the effects will cancel out when CN ratios relative to a reference is calculated. Using the notation of Bengtsson et al. (2008b), we use constant target functions gTr(λ)=log2(2200), where 2200 was chosen arbitrarily.

Define 𝒥Nsp, 𝒥Sty, 𝒥Nsp∩Sty ⊂ 𝒥 to be the subsets of loci that are exclusive to NspI, StyI and to both enzymes, respectively. In order to simplify the notation, we will use the same notation for the true and the estimated functions. The normalization algorithm for array i = 1,…, I is then:

For each enzyme r∈{Nsp, Sty}, fit a smooth spline gri(·) robustly to {(λrj, log2θij)} based on copy-neutral loci j∈𝒥r ∩ 𝒥* that are exclusive to restriction enzyme r. This constitutes the fragment-length effect for enzyme r in the sample i.

- For each enzyme r∈{Nsp, Sty}, calculate the PCR discrepancies for sample i based on all loci j∈𝒥r that are exclusive to restriction enzyme r as

(10) - For remaining loci j∈𝒥Nsp∩Sty, calculate the discrepancies as

where

(11)

and gNsp∩StyT(λNsp, λSty) defined analogously.

(12) - Finally, normalize all loci (on the intensity scale) by

(13)

Loci for which annotation is missing (see Supplementary Material) are rescaled such that their median signal equals the median of the other loci. For chip types such as 10K, 100K and 500K, where there are no multi-enzyme loci (𝒥Nsp∩Sty=∅), Step 3 no longer applies and the method becomes effectively identical to the one presented in Bengtsson et al. (2008b) (if the target effect is estimated from the average array). Moreover, since each gri(·) includes the term ρri, the above method will also control for imperfect mixing of enzyme products, which otherwise carry through introducing systematic effects in loci that originate from both digestions. Analogously, the scale differences between arrays, {κi}, are also controlled for.

2.2.5 Normalization for GC-content effects

As in our previous study, we did not find any significant GC-content effects remaining after applying CRMA v2, and correcting for it did not improve the performance. For this reason, we do not consider GC-content normalization here. We wish to note that this does not necessarily contradict other studies that report strong GC-content effects. The reason for this may be due to differences in the preprocessing methods, especially in how they correct for offset. Consistent with previous discussion, normalization for GC-content effects can be done in a single-array manner.

2.2.6 Calculation of raw CNs

CRMA v1 and CRMA v2 both calculate raw CNs as the chip effect relative to a reference. This is the only step in CRMA v2 requiring a reference. We calculate the relative CN for sample i and locus j as:

| (14) |

where  is the reference signal, which commonly is the robust average across samples and possibly corrected for the case that some data points are from non-copy-neutral loci, cf. Bengtsson et al. (2008b). Note that for paired studies such as tumor-normal comparisons, the normal DNA will serve as the reference, which is why only two hybridizations are needed in such comparisons. In Equation (14), we assume that the mean of

is the reference signal, which commonly is the robust average across samples and possibly corrected for the case that some data points are from non-copy-neutral loci, cf. Bengtsson et al. (2008b). Note that for paired studies such as tumor-normal comparisons, the normal DNA will serve as the reference, which is why only two hybridizations are needed in such comparisons. In Equation (14), we assume that the mean of  corresponds to CN = 2, e.g. ChrY reference estimates should be rescaled accordingly. For CN estimates on the logarithmic scale, we calculate:

corresponds to CN = 2, e.g. ChrY reference estimates should be rescaled accordingly. For CN estimates on the logarithmic scale, we calculate:

| (15) |

Note that the latter is not defined for zero CN levels (or for negative levels occurring due to noise).

2.2.7 Filtered and non-filtered set of loci

Regardless of whether CN analysis will be conducted on a filtered or the full set of loci, we recommend that all preprocessing is done on the full set and filtering is applied only after obtaining raw CNs. The rationale for this is that we believe the main systematic effects are the same for the filtered and the full set and that one can estimate these effects more accurately using the latter. This also has the advantage that the preprocessing will be the same regardless of which set is used in the end.

2.3 Implementation

The above preprocessing method, referred to as CRMA v2, is available as part of aroma.affymetrix (Bengtsson et al., 2008a) implemented in R (R Development Core Team, 2008). The method is designed and implemented to have bounded-memory usage, regardless of the number of arrays. Since it is a single-array method, the arrays can be processed in parallel on multiple hosts/processors.

2.4 Datasets

Two publicly available datasets were used in this study.

2.4.1 Normal dataset

GWS6 CEL files for the 30 male and 30 female CEU founders of The International HapMap Project (Altshuler et al., 2005; The International HapMap Consortium, 2003) were used. Offspring were excluded in order to avoid biological relationships. Because female NA12145 has a low true ChrX CN level (Ting et al., 2006), it was excluded from the evaluation.

2.4.2 Tumor-normal dataset

All 68 GWS6 CEL files of the GEO dataset GSE13372 (Chiang et al., 2009), which among other samples contains 21 replicated tumor-normal HCC1143 (breast ductal carcinoma) pairs, were processed. The evaluation was done on the first tumor-normal HCC1143 pair. More details on the above datasets can be found in the Supplementary Material.

2.5 Methods for evaluation

In order to assess the performance of CRMA v2, we compared it with Affymetrix CN5 method (Affymetrix Inc., 2008) and the method implemented in dChip (Li and Wong, 2001). For dChip, we found that summarizing SNP probes by averaging is significantly better than using the default multiplicative model. For this reason, we only present results for the former (here denoted by dChip*). Moreover, since the CN5 implementation is limited to the default CDF, the results presented here are based on that set of loci. As outlined below, we base the evaluation on the aforementioned data sets using a multi-sample evaluation and a single-sample single-changepoint evaluation, respectively. Further details are available in the Supplementary Material.

2.5.1 Multi-sample ChrX and ChrY evaluation

For the normal dataset, we used the same set of receiver operator characteristics (ROC) evaluation methods as in Bengtsson et al. (2008b) using relative [Equation (14)] instead of log-ratio CNs [Equation (15)]. To assess how well the methods differentiate between one and two copies, and zero and one copy, we use ChrX and ChrY data, respectively. We exclude loci in pseudo-autosomal regions (Blaschke and Rappold, 2006) and inside and close to known CN polymorphic regions (Redon et al., 2006), leaving 68 966 ChrX loci and 5718 ChrY loci. Since CN5 uses only females (males) for the reference signals  on ChrX (ChrY), this comparison study will not use bias-corrected reference signals from all samples (Bengtsson et al., 2008b).

on ChrX (ChrY), this comparison study will not use bias-corrected reference signals from all samples (Bengtsson et al., 2008b).

2.5.2 Single-sample evaluation at a set of changepoints

For the tumor-normal dataset, we selected one tumor-normal pair for which we identified a set of regions each containing a single CN change point. Data points in a 500 kb region centered on each change point were excluded. The remaining data points are annotated to belong to either the copy-neutral state or the copy-aberrant state. Contrary to the evaluation on the normal dataset, the true CN levels are not known except that they are either gains or losses. Next, for each CN region we use ROC analysis to assess how well the raw CNs separate between the neutral and the aberrant data points. This evaluation is done on the full-resolution CNs as well as smoothed CNs, where the CNs are smoothed by using non-overlapping bins for which the average of CNs is calculated. This approach was inspired by studies such as Lai et al. (2005), Willenbrock and Fridlyand (2005) as well as Bengtsson et al. (2009).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Multi-sample evaluation

3.1.1 Differentiating CN = 1 and CN = 2 (ChrX)

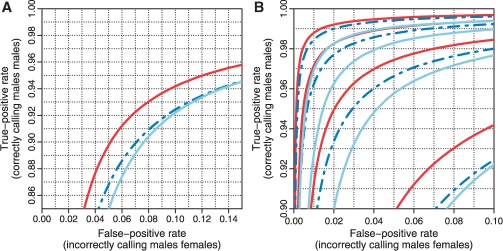

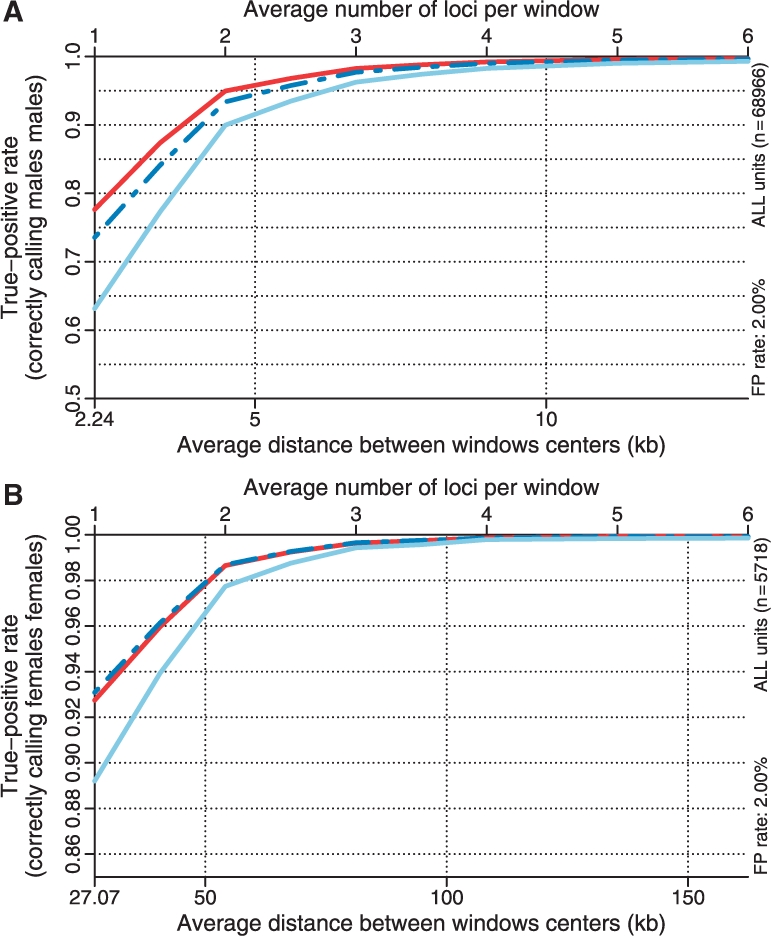

As explained in detail in Bengtsson et al. (2008b), we use ChrX data to assess how well a set of CN estimates can differentiate between the CN = 2 (females) state and the CN = 1 (males) state. The idea is to call the CN state for each locus given a global threshold, where a locus with a CN estimate below the threshold is considered to belong to the CN = 1 state, otherwise the CN = 2 state. By calculating the fraction of correctly called CN = 1 loci, we obtain an estimate of the true-positive rate, and by calculating the fraction of incorrectly called CN = 2 loci, we obtain an estimate of the false-positive rate. By adjusting the threshold, we can estimate the ROC curve. The true-positive rate of calling a CN = 1 locus correctly (among CN = 2 loci) as a function of false-positive rate is depicted in Figure 1 for each of the three methods. The ROC curves show that CRMA v2 separates CN = 1 from CN = 2 better than CN5, which in turn is better than dChip*. This is true both at the full resolution (H = 1) and at various amounts of smoothing. We also note that CRMA v2 smoothed with three loci per window performs as well as or better than dChip* smoothed with four loci per window (see also Fig. 2). In this ROC analysis, which is based on 68 966 loci in 59 samples, there were in total 2 000 014 CN = 1 (male) loci out of 4 068 994 loci.

Fig. 1.

ROC curves showing that CRMA v2 (solid red) separates CN = 1 from CN = 2 (ChrX) better than CN5 (dashed blue) and dChip* (solid light blue) at the full resolution (H = 1; A) as well as at various amounts of smoothing (H = 1, 2, 3, 4; B). The curves for H = 1 are in the lower right corner and the curves for H = 4 are in the upper left corner.

Fig. 2.

The true-positive rate as a function of resolution/smoothing at a 2.0% false-positive rate for the different methods. The results for the CN = 2 versus CN = 1 (ChrX) test is depicted in (A) and the results for the CN = 1 versus CN = 0 (ChrY) test in (B). Note the different scales. See Figure 1 for legends.

Using a windowing technique similar to that in Bengtsson et al. (2008b), for a fixed false-positive rate we can estimate the true-positive rate as a function of amount of smoothing. Since a given amount of smoothing corresponds to a given distance between loci this provides us with a first approximation to the effective resolution of a method. In Figure 2A, the true-positive rate (for CN = 2 versus CN = 1) as a function of resolution is shown for the three methods, which shows that CRMA v2 has a higher resolution.

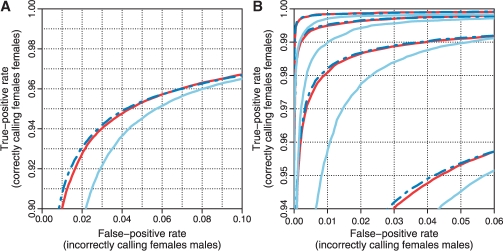

3.1.2 Differentiating CN = 0 and CN = 1 (ChrY)

Identifying a CN = 0 locus among CN = 1 loci is easier than identifying a CN = 1 locus among CN = 2 loci. This is because the distance between CN = 0 and CN = 1 is greater than that between CN = 1 and CN = 2, relative to the reference level (and noise level). This is also confirmed by comparing the corresponding true-positive rates at a given false-positive rate (Figs 1 and 3) at the full resolution or at various amounts of smoothing (Fig. 2). The results also show that CN5 is as good as or slightly better than CRMA v2 at differentiating CN = 0 from CN = 1, and both are better than dChip*. In this ROC analysis, which is based on 5718 loci in 59 samples, there were in total 150 162 CN = 0 (female) loci out of 305 502 loci.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves showing CRMA v2 differentiates between CN = 1 and CN = 0 (ChrY) as well as or slightly worse than CN5, and better than dChip* at the full resolution (A) as well as at various amounts of smoothing (B). See Figure 1 for legends.

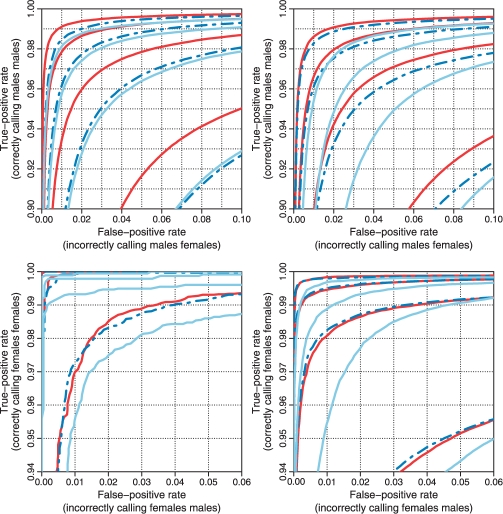

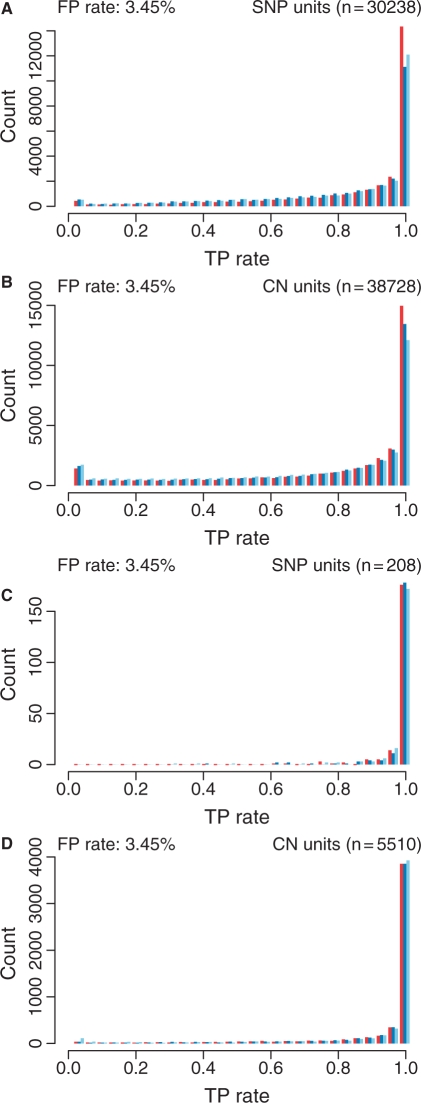

3.1.3 Performance of SNPs and CN loci

In order to better understand differences between methods, we compare the ROC curves and distribution of true-positive rates at a given false-positive rate, while stratifying on SNP and CN loci. We observe that on average the discriminatory power is greater for SNPs than CN loci (Fig. 4). CN5 is the method for which SNPs and CN loci have the most similar performances. Furthermore, by investigating the locus-by-locus ROCs, we observe that the true-positive rates at a fixed false-positive rate tend to be greater for SNPs than for CN loci (Fig. 5), and that there is a significant set of CN loci with very low true-positive rates. The dChip* method has a larger set of poorly performing CN loci, which is also seen when comparing dChip's ROC curves for SNPs and CN loci. For the ChrX-based analysis, 30 238 SNPs and 38 728 CN loci were used, and for the ChrY-based analysis, 208 SNPs and 5510 CN loci were used.

Fig. 4.

The methods' performances on SNPs (left) and CN units (right) when testing for CN = 2 versus CN = 1 (ChrX; upper) and CN = 1 versus CN = 0 (ChrY; lower). The panels show the ROC curves for CRMA v2 (solid red), CN5 (dashed blue) and dChip* (solid light blue) at H = 1, 2, 3, 4 amounts of smoothing.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of true-positive rates for SNPs (A and C) and CN units (B and D) for CRMA v2 (left bars; red), CN5 (middle bars; blue) and dChip* (right bars; light blue) when testing for CN = 2 versus CN = 1 (ChrX; A and B) and CN = 1 versus CN = 0 (ChrY; C and D) while fixing the false-positive rate (3.45%). No smoothing was applied.

3.2 Single-sample evaluation

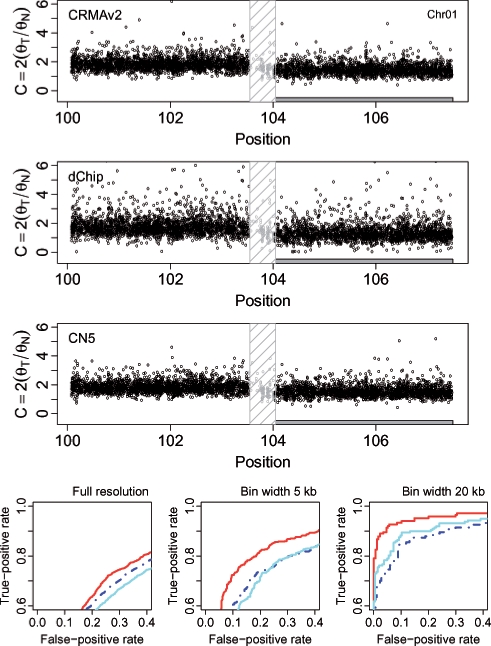

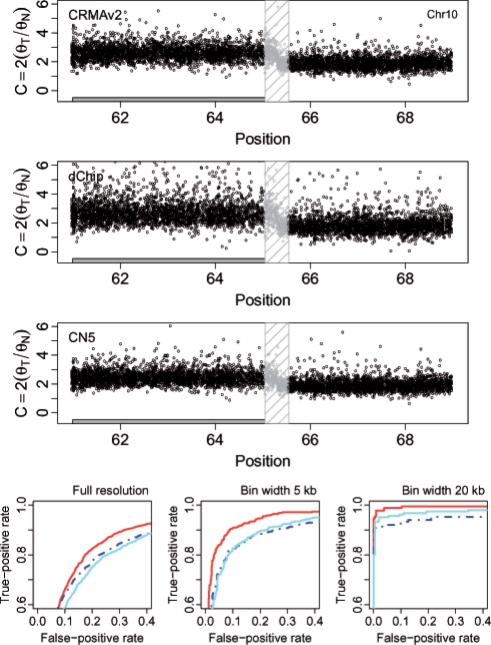

For the tumor-normal pair HCC1143, we calculated how well CN estimates of loci that are either gains or losses separate from estimates of copy-neutral loci. Figures 6 and 7 show the CN estimates and the performance for a 7.4 Mb region on Chr 1 and a 9.0 Mb region on Chr 10, respectively. The former contains a loss (2074 out of 4316 loci) and the latter a gain (2805 out of 5285 loci). The ROC results show that CRMA v2 identifies the aberrant states better than or as well as dChip* and CN5. We wish to emphasize that in order for CRMA v2 to provide CN estimates for this tumor-normal pair only two CEL files were required. For dChip* and CN5, all 68 CEL files were used in order to obtain CN estimates. Results for additional CN regions and amounts of smoothing can found in the Supplementary Material.

Fig. 6.

The region 100.1–107.5 Mb on Chr 1 in tumor-normal sample HCC1143 has a change point at ∼103.8 Mb, which separates a copy-neutral state (left) from a loss (right). There are 2242 and 2074 loci in these two states, respectively (totaling 4316 loci). The top three rows show the raw CNs [Equation (14)] of the CRMA v2, the dChip and the CN5 methods, respectively. The 500 kb safety region around the change point with data points excluded in the evaluation is highlighted by a dashed frame. The three panels in the bottom row show the ROC performance of the three methods at the full resolution, and after binning the CNs in non-overlapping windows of size 5 and 20 kb, respectively. See Figure 4 for legends.

Fig. 7.

The region 61.0–69.0Mb on Chr 10 in tumor-normal sample HCC1143 has a change point at ∼65.3 Mb, which separates a gain (left) from a copy-neutral state (right). There are 2805 and 2480 loci in these two states, respectively (totaling 5285 loci). See Figure 6 for content and legends as in.

4 DISCUSSION

We conclude that it is possible for a single-array method such as CRMA v2 to produce non-polymorphic CN estimates that discriminate two CN states as well as or better than existing multi-array-based methods. In the above sections, we have tried to point out the main attributes of each preprocessing step that allow CRMA v2 to become a single-array method. In order to further clarify why this is possible, we would like to underline that there is a distinction between models that include parameters shared by multiple arrays, and algorithms that are applied to multiple arrays. The main rationale for using multi-array models (Li and Wong, 2001), was removed when Affymetrix designed the newer arrays to have identically replicated SNP probes. Having said this, we believe that several existing preprocessing methods, such as CN5 and dChip, naturally allow themselves to be turned into single-array methods (without having to rely on a priori parameter estimates).

Confirming previous observations, we found that it is harder to differentiate between CN = 1 and CN = 2 than between CN = 0 and CN = 1. We believe that this trend will be true for higher CN levels, i.e. it will be increasingly difficult to separate higher CN levels from each other. We also found that the SNPs show better discrimination for CN than the CN loci. We look forward to further studies investigating whether this is because more/multiple probes are used for the SNPs or there are other reasons for this. Also, an assessment is still needed of how well CRMA v2 (and other methods) controls for systematic effects between labs and batches, and whether additional normalization is needed in such cases.

We also wish to emphasize that the dChip method has not been optimized for GWS or SNP arrays, which may explain its lower performance in this GWS6 study in comparison with its higher performance for the 500K arrays (Bengtsson et al., 2008b).

CRMA v2 provides neither allele-specific nor CN estimates calibrated toward true CN levels. Allele-specific CNs are needed in order to identify events such as copy-neutral loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH). With calibrated allele-specific CNs, genotyping algorithms can be generalized to call genotypes beyond the traditional diploid AA, AB and BB states. We are currently working on an extension to CRMA v2 that will provide full-resolution calibrated allele-specific CN estimates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Ben Bolstad, Simon Cawley and Jim Veitch at Affymetrix Inc. for technical support and scientific feedback. We also thank Cheng Li at the Harvard School of Public Health for details on the dChip method and software, and the reviewers for constructive feedback.

Funding: Wenner-Gren Foundation (to H.B. ); the American-Scandinavian Foundation (to H.B. ); the Solander Foundation (to H.B.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Affymetrix Inc. Genome-Wide Human SNP Nsp/Sty 6.0 User Guide. 2007a Affymetrix Inc. Rev 1. Available at http://www.affymetrix.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Affymetrix Inc. Genome-Wide Human SNP Nsp/Sty Assay 5.0. 2007b Affymetrix Inc. Rev 2. Available at http://www.affymetrix.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Affymetrix Inc. Affymetrix Genotyping Console 3.0 - User Manual. 2008 Affymetrix Inc. Available at http://www.affymetrix.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, et al. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson H, et al. Calibration and assessment of channel-specific biases in microarray data with extended dynamical range. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson H, et al. Technical Report 745. Berkeley: Department of Statistics, University of California; 2008a. aroma.affymetrix: a generic framework in R for analyzing small to very large Affymetrix data sets in bounded memory. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson H, et al. Estimation and assessment of raw copy numbers at the single locus level. Bioinformatics. 2008b;24:759–767. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson H, et al. A single-sample method for normalizing and combining full-resolution copy numbers from multiple platforms, labs and analysis methods. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:861–867. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder H, et al. Sensitivity of microarray oligonucleotide probes: variability and effect of base composition. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:18003–18014. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke RJ, Rappold G. The pseudoautosomal regions, shox and disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho B, et al. Exploration, normalization, and genotype calls of high-density oligonucleotide SNP array data. Biostatistics. 2007;8:485–499. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxl042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang DY, et al. High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Method. 2009;6:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WR, et al. Comparative analysis of algorithms for identifying amplifications and deletions in array CGH data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3763–3770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong W. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naef F, Magnasco MO. Solving the riddle of the bright mismatches: labeling and effective binding in oligonucleotide arrays. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter Phys. 2003;68(1 Pt 1):011906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon R, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting J, et al. Analysis and visualization of chromosomal abnormalities in SNP data with SNPscan. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbrock H, Fridlyand J. A comparison study: applying segmentation to array CGH data for downstream analyses. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4084–4091. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirapati P, Speed T. WEHI Bioinformatics Technical Report. Australia: Walter & Elisa Hall Institute of Medical Research; 2002. An algorithm to fit a simplex to a set of multidmensional points. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, et al. A model based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004;99:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, et al. Free energy of DNA duplex formation on short oligonucleotide microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.