Abstract

Motivation: Primary data analysis methods are of critical importance in second generation DNA sequencing. Improved methods have the potential to increase yield and reduce the error rates. Openly documented analysis tools enable the user to understand the primary data, this is important for the optimization and validity of their scientific work.

Results: In this article, we describe Swift, a new tool for performing primary data analysis on the Illumina Solexa Sequencing Platform. Swift is the first tool, outside of the vendors own software, which completes the full analysis process, from raw images through to base calls. As such it provides an alternative to, and independent validation of, the vendor supplied tool. Our results show that Swift is able to increase yield by 13.8%, at comparable error rate.

Availability and Implementation: Swift is implemented in C++and supported under Linux. It is supplied under an open source license (LGPL3), allowing researchers to build upon the platform. Swift is available from http://swiftng.sourceforge.net.

Contact: new@sgenomics.org; nava.whiteford@nanoporetech.com

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Second generation sequencing technologies such as the Genome Analyzer (Illumina, San Diego, USA), 454-FLX (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and SOLiD (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) have increased the production of sequence data by several orders of magnitude (Quail et al., 2008). Along with an increase in throughput these technologies bring an increased primary data analysis problem, both in terms of the complexity of the analysis and the volume of data that needs to be processed. Second generation devices image a surface to which clusters of DNA grown from a template or beads have been attached. The data analysis problem, therefore, first presents itself as one of image analysis, the result of which is a sequence of intensities which require further signal corrections to produce base calls (Brown et al., 2006). A number of new base-calling methods have been developed including Altacyclic (Erlich et al., 2008) and Rolexa (Rougemont et al., 2008). However, to our knowledge no image analysis methods have been developed aside from the proprietary implementation provided by the vendor.

In this article, we present Swift, an open source primary data analysis package for the Illumina Solexa sequencing platform which performs image analysis and base calling. Swift is the first freely available solution to the primary data analysis problem ‘from images to base calls’ and is available under the LGPL3 at http://swiftng.sourceforge.net. We perform validation against a ϕX 174 dataset.

The use of benchmark datasets is well established for the validation of analysis methods for gene expression (Cope et al., 2004; Holloway et al., 2006) and genotyping (Lin et al., 2008) microarrays. To facilitate algorithm development and comparison for the Illumina Solexa platform, we have made the raw files from a ϕX 174 dataset available from our web site. This dataset, which provides a stable reference against which sequencing errors may be determined, is used to assess the performance of our approach.

2 METHODS

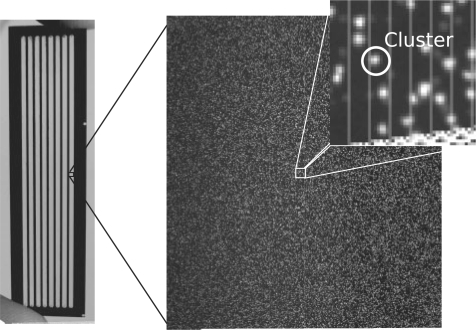

In Illumina Solexa sequencing template, DNA sequences are attached to a flowcell (shown in Fig. 1). ‘Clusters’ of single-stranded DNA are grown from these single molecules and the prepared flowcell is placed in the sequencing device for imaging. Sequencing occurs as a cyclic process. A cycle of chemistry is performed which synthesizes a single fluorescently labelled complementary base to each DNA molecule (Bentley et al., 2008). The clusters are then imaged four times per cycle using two different lasers and two filters to detect the excitation of the four labelled nucleotides. The primary data analysis problem is therefore to take sets of images from the device and extract base calls from them. In an ideal scenario, a cluster would fluoresce in a single channel and the sequence of the template could be readily determined. However, the intensity vectors are not purely responsive to one distinct base and there are several signal artefacts present which must be corrected for in order to achieve accurate base calls.

Fig. 1.

A Genome Analyzer flowcell (left) and imaging region or ‘tile’ (right), with a magnified section showing a cluster. Images have been normalized, to span the full grey-scale range, for illustration purposes.

2.1 Image analysis

In each cycle, the flowcell is imaged in a series of non-overlapping regions (Fig. 1). The number of regions (known in Illumina terminology as ‘tiles’) depends on the device configuration. The default configuration for a Genome Analyzer 2 is 100 tiles per lane, where there are eight lanes per flowcell. Tiles are separated by a margin to prevent clusters being imaged multiple times. The flowcell is moved under the camera in order to image each tile in each cycle. Therefore, during each cycle 800 tiles are imaged in four channels. Runs are typically around 37 cycles producing a total of 118 400 images. Each GA2 image is a 2048 × 1794 pixel 16 bit grey-scale TIFF (though only 12 bits contain data). Each pixel covers ∼0.14 μ2 of the flowcell and ∼9 pixels comprise one cluster object.

In Swift, the unit of analysis is a set of images covering a single tile. These undergo image analysis the result of which is an intensity vector, for each cluster (a total of 148 intensity values, per cluster, for a 37 cycle run).

2.1.1 Background subtraction

The removal of non-specific ‘background’ intensity is desirable in order to obtain a less-biased measure of the true signal. For microarrays, it has been shown that subtracting a conservative estimate of the local background performs well, and avoids negative intensities (Ritchie et al., 2007), which are undesirable in downstream analysis and, as described below, possible in the GAPipeline (Brown et al., 2006). We therefore take the conservative approach of morphological erosion (Serra, 1983) in Swift. In this method the minimal pixel value within a window around each pixel is subtracted from the central pixel's value. For efficiency, we use a square structuring element and implement the process using a FIFO queue.

2.1.2 Image correlation

In each cycle, the stage supporting the flowcell is moved to each tile position in turn. This repositioning is not entirely accurate and between cycles images may be several pixels out of alignment. We must therefore bring the images within each channel into alignment to compensate for this. A reference cycle is selected (typically the first cycle) to which subsequent images are aligned. Images are thresholded for alignment, discarding noise, using the method described in the following section. Alignment is performed by cross-correlating the images at the pixel level. Registering images to subpixel resolution was found unnecessary. This step may be performed efficiently using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) (Castro and Morandi, 1987). Swift uses the FFTW library (Frigo and Johnson, 1998) to implement this process.

To allow for a variation in offsets across the image (due perhaps to incorrect focusing, or warping of the flowcell due to temperature variation), we divide the image into regular regions and calculate and apply offsets in each region independently. After this cross-cycle registration step, images within each channel should be in alignment. In order to make this process robust, the median channel offsets are used, as all imaging channels should be subject to the same stage movement.

Though each channel is now in alignment from cycle to cycle, an offset still exists between channels. This offset is due to the different dye emission frequencies, and therefore differences in the optical path. In order to compensate for this offset an aggregate image is constructed for each channel, which simply sums the intensities from all cycles creating a reference image which should contain all clusters. The reference image for each channel is correlated against the other channels and from this cross-channel offsets are determined. Once these offsets are applied all images should be in alignment and we can begin to identify objects and extract their intensities.

2.1.3 Object identification and intensity extraction

Images are thresholded in order to identify foreground (cluster) pixels. In order to threshold the image, we create a morphologically dilated (Serra, 1983) image and threshold those pixels in the original image that are within a given fraction of their dilated value. These parameters may be adjusted by the user. The process is implemented efficiently using a FIFO queue and square structuring element. This thresholding scheme is invariant to the differences in illumination commonly seen in Genome Analyzer image data. Reference contours are produced for each cluster, formed from groups of four-connected foreground pixels. Reference contours are created from non-overlapping objects in first cycle images by default.

Once we have a set of reference contours for each cluster, the maximum pixel intensity within the contour is extracted from the background subtracted, aligned images. This process is performed for each cluster across cycle. The result is a sequence of four intensities per cycle across N cycles.

2.2 Base calling

If no artefacts were present in the signal, we could now simply ‘call’ the maximum intensity as the base call. However, a number of artefacts are present making the post-image analysis signal correction problem significant. Several tools exist for solving this post-image analysis, or base-calling, problem (Erlich et al., 2008; Rougemont et al., 2008). Swift is able to output a GAPipeline-style intensity file, allowing it to be used with any of these tools. However, Swift also provides its own base-calling algorithms allowing complete end to end operation using a simple but efficient and robust approach. In contrast to the existing tools, Swift does not employ machine learning or statistical modelling but rather applies a series of corrections to the signal a methodology similar to that employed in the GAPipeline.

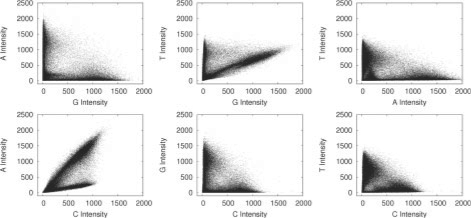

2.2.1 Crosstalk correction

The first artefact we must correct for is crosstalk. This is caused by an overlap in the dye emission frequencies. Simply put, the C channel illumination overlaps with the A, causing a C label to produce a small amount of illumination in the A channel, and similarly the G and T dye responses also overlap. Figure 2 shows crosstalk plots typical of those produced by a Genome Analyzer 2. In order to correct for this we use a method similar to (Li and Speed, 1998) with a few minor differences. The basic method puts regression lines through the arms of the plots. The arms are identified by placing bins along with X- and Y-axis and detecting the minimum values in these bins. Linear regression is performed on these values and the slope is used to derive a correction matrix. This process is performed iteratively until almost no slope remains. In Swift, we also perform some basic outlier detection, by placing a number of bins across the crosstalk plot and removing those containing few points.

Fig. 2.

Pairwise intensity plots from cycle 1 of a Genome Analyzer 2 run. Unlike pairwise plots produced by capillary sequencing (Li and Speed, 1998) many Genome Analyzer plots have a distinctive ‘bowed’ appearance.

Some Genome Analyzer datasets produce deviations in crosstalk, which appear intensity dependent. This produces slightly ‘bowed’ plots as seen in Figure 2. Placing a linear regression though the minimal values produces poor results and we therefore adopt a second strategy in addition to the method described to cope with this scenario. In this method, we identify a set of clusters (using the chastity metric described below) where it is likely that the correct base call can easily be determined, and then perform a linear regression on these values and derive a correction matrix as before. Figure 3 shows the pairwise intensity plots after correction.

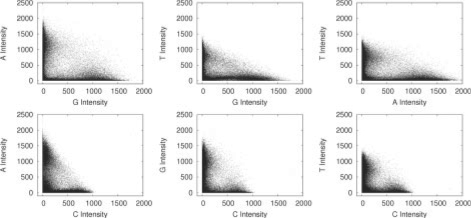

Fig. 3.

Pairwise intensity plots from cycle 1 of a Genome Analyzer 2 run after crosstalk correction.

After crosstalk correction negative values, which represent an over-correction, are removed. The resultant signal is re-expressed as a deviation from the median intensity value in each channel. This normalization provides a fixed reference point for signals. We believe this may help compensate for any build up in background intensity, such as the common ‘sticky-T’ phenomenon, due to incomplete cleavage of the T-dye.

2.2.2 Phasing correction

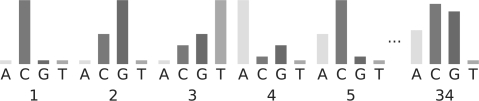

As previously stated each cluster contains many identical copies of a template sequence. During each cycle, labelled nucleotides are incorporated into these molecules. However, this is driven by stochastic chemical processes, so some molecules may fail to incorporate a labelled nucleotide, or may fail to block and incorporate >1 nt. This manifests itself as a leakage in intensity between cycles. For example, if a G base is present in cycle 2, we will see a small amount of G intensity leaking into cycles 1 and 3. Figure 4 illustrates forward phasing.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of phasing in Illumina Solexa sequencing. The figure shows intensities detected across cycle where the true sequence reads CGTAC… Cross-cycle signal leakage can be seen, for example, in cycle 2 which contains a significant fraction of the intensity present in cycle 1. By the final cycle, the signals are almost fully convolved and it becomes difficult to determine the true signal. Phasing is caused by the non-incorporation of a labelled nucleotide in a given cycle. The reverse phenomenon (data not shown) is caused by the multiple incorporation of nucleotides and manifests itself as signal leakage between the current and previous cycles.

To correct this, we rank clusters by ‘Chastity’ (described in the following section) and use the top 400 clusters to estimate phasing. We correct each cycle and channel independently. For each channel, we identify those clusters which are brightest in the current channel, but whose maximal intensity is not this channel in previous and subsequent cycles. From these we calculate the fraction of the intensity that has leaked between cycles and use this as our phasing estimate.

This phasing estimation is then applied as a correction where this fraction of the current cycle's intensity is subtracted from subsequent and previous cycles and added to the current cycle. A limit is placed upon the phasing estimation to ensure that unreasonable values are not used. The correction is applied iteratively starting with the first cycle, then correcting for each subsequent cycle's phasing.

2.2.3 Chastity filtering

In the ideal scenario discrete clusters are grown, each from a single DNA template. However, mixed clusters can be grown starting from more than one template, in which case the base calls of the cluster cannot be accurately determined. Swift uses the same metric as the GAPipeline to filter out these clusters. The metric is defined as follows:

| (1) |

In the GAPipeline, a limit is placed on the second lowest value of chastity over the first 25 bases. By default this is set as 0.6. As this is a robust and well-validated metric it is also used in Swift, with a user-selectable threshold.

2.2.4 Base calling

After correction, the base with the maximum intensity is chosen as the called base. Swift can also optionally produce a Fast4 file. This file contains the raw probabilities for all four bases. This additional information may prove useful in alignment. Base probabilities are simply calculated as a fraction of the total intensity. Fastq files may also be created. The value used is derived from the probability of the called base scaled over the range Q6–Q30. As with all quality scores this value requires calibration in order to provide a useful metric.

2.2.5 Comparison with the GAPipeline

GAPipeline (the vendor-supplied analysis tool) performs image analysis, base calling and alignment (optional) and is composed of a number of independent programs. The UNIX ‘make’ utility is used to manage workflow and job control. Figure 5 shows the processing steps common to Swift and the GAPipeline. In this section, we briefly discuss our investigation of the GAPipeline's methods, based on the release prior to GAPipeline 1.0. A detailed description of our analysis is also available (http://sgenomics.org/mediawiki/upload/8/80/Pipeline.pdf).

Fig. 5.

Processing steps required to process primary data from images to base calls.

Processing begins with Firecrest, the GAPipeline image analysis tool. Firecrest operates in two passes. In the first pass a full image analysis is performed but only the offsets between imaging channels are retained. The second pass then applies these offsets between channels. This differs from Swift which aligns images within each channel and then performs alignment on aggregate reference images in a single pass. Firecrest begins by applying a Mexican hat filter to each image. This attenuation of high and low frequencies smoothes the image and strengthens the edges. The image is broken into an even number of regions >125 pixel square for noise and background estimation. A smoothed, filtered histogram of the pixels in each region is created to which a Gaussian is fitted. The average calculated from the Gaussian is used to populate a ‘background’ image, the SD a ‘noise’ image, a single value is used for each 125 pixel square region. The ‘background image’ is subtracted and then thresholded for object identification. Thresholding retains pixels whose value is greater than four times the value in the ‘noise image’. This differs significantly from Swift where the background subtraction and thresholding varies smoothly across the image, adapting for local intensity variation.

In Firecrest, objects >15 pixels but <115 pixels are split producing two objects, one at the maximum pixel value, another at the second highest. In contrast to this, Swift performs no deblending by default. In general, the deblending of an object may be one source of ‘optical duplicates’ where multiple clusters are identified where only one true cluster exists. This is best avoided if possible.

In Firecrest, once objects have been identified local background is compensated for. This takes a 10 × 10 window around the pixel of maximum intensity in an object. The median of all pixels not within the object is taken (some basic outlier removal is performed) and subtracted from the objects maximal intensity value (this is designed to compensate for local background noise). In contrast to Swift, this often produces non-integer and negative values. Swift avoids this producing only positive integers as its output of image analysis. This not only simplifies later processing, but also reduces the cost of archival.

The pixel of maximum intensity in each object has a parabolic fit applied to it and the values of adjacent pixels, which produces a position at subpixel resolution. In order to bring the images into alignment, synthetic images are constructed from the reference positions (a Gaussian distribution of intensities is created, centred around this position). The synthetic images are cross-correlated in 125 × 125 pixel regions, producing an X/Y offset in each region. A linear regression is fitted to the X and Y offsets calculated in order to determine a scaling factor (this assumes the offsets deviate linearly across the tile). In contrast, Swift uses the object profiles identified after thresholding on subregions of the image. Swift does not apply a linear fit to the data, as our investigation shows that the offsets do not vary linearly across the tile (Fig. 6).

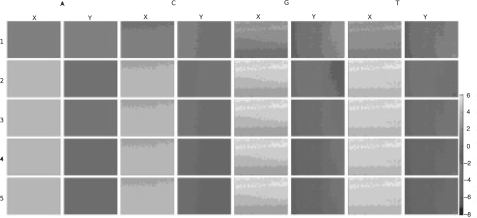

Fig. 6.

X and Y offsets per channel calculated by Swift on the first five cycles of run 1851 lane 4, tile 1. Offsets were calculated independently in 400 subregions of each image. Many of these offset maps do not exhibit a linear variation across the tile.

Once in alignment, the pixels lying under the reference positions are extracted, producing an intensity vector for each cluster. This intensity vector is then passed on to a script which performs crosstalk correction using the method of (Li and Speed, 1998). A phasing correction is then performed. We have not examined the GAPipeline post-image analysis corrections in great detail, though it is apparent that no explicit normalization is performed and that other than this our methods are similarly motivated.

3 RESULTS

In this section, we discuss the validation of Swift against five tiles of ϕ X174 control from a 37 cycle single-end Genome Analyzer 2 run. A full set of tile images, intensity files and base calls is available from http://sgenomics.org/swift/paperdataset.html. A comparably small dataset was chosen in order to allow us to make the full dataset available. We identify clusters from the first three cycles. In doing so, we run the risk of producing ‘optical duplicates’, that is, identifying multiple clusters, and therefore reads, where there is only really one. In order to mitigate this effect, we apply an optical duplicate filter. This filter removes those duplicate reads within a 6 × 6 window with similar sequence (allowing eight mismatches), and retains the read with the highest ‘chastity’. No optical duplicate filtering was performed for the GAPipeline. Settings may be tuned to reduce the duplicate rate, however, this will result in a reduction in yield. We compare the Swift output with version 1.3.2 of the Illumina GAPipeline. Table 1 summarizes these results. Default parameters were used for the GAPipeline. Swift produced an average increase in yield of 13.8% while maintaining a similar error rate. The user may tune Swift's parameters to reduce the optical duplicate rate, error rate or increase yield as desired.

Table 1.

Comparison of Swift and GAPipeline 1.3.2 error rates for given tiles on Sanger Institute run 1851 lane 4

| Swift |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile no. | Total reads | Dups. Rem. | PF | Err. (%) |

| 1 | 333 345 | 192 103 | 100 697 | 1.20 |

| 21 | 288 498 | 158 540 | 96 923 | 0.97 |

| 41 | 286 302 | 150 220 | 88 374 | 1.05 |

| 61 | 276 433 | 146 407 | 92 247 | 1.00 |

| 81 | 280 069 | 155 752 | 98 872 | 1.00 |

| GAPipeline 1.3.2 |

Swift yield |

|||

| Tile no. | Total reads | PF | Err. (%) | Inc. (%) |

| 1 | 112 353 | 79 548 | 1.10 | 26.6 |

| 21 | 108 588 | 85 330 | 1.04 | 13.6 |

| 41 | 101 574 | 79 453 | 1.13 | 11.2 |

| 61 | 104 237 | 84 658 | 1.16 | 8.9 |

| 81 | 112 546 | 90 996 | 1.04 | 8.6 |

This lane contained ϕX 174, a commonly used control genome. Sequences were aligned using PhageAlign from the GAPipeline version 1.3.2. The GAPipeline performed its own alignment. Default parameters we used for the GAPipeline. As can be seen Swift provides an average increase in yield of 13.8% at comparable error rate.

In order to determine whether improvements come from image analysis or base calling, we analysed intensity files from the GAPipeline using Swift (Table 2). The results show a small increase in yield over the GAPipeline in most cases, but no reduction in error rate. This indicates that Swift's improvements come for the most part from the image analysis. We do however note that the number of optical duplicates removed is lower.

Table 2.

Comparison of Swift and GAPipeline 1.3.2 Image analysis when used in conjunction with the Swift basecaller, as for Table 1

| GAPipeline 1.3.2 + Swift |

Swift yield |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile no. | Total reads | Dups. Rem. | PF | Err. (%) | Inc. (%) |

| 1 | 112 925 | 112 503 | 92 345 | 1.12 | 9.05 |

| 21 | 108 588 | 108 190 | 91 022 | 1.12 | 6.48 |

| 41 | 101 574 | 101 171 | 85 281 | 1.15 | 3.63 |

| 61 | 104 237 | 103 782 | 87 455 | 1.24 | 5.48 |

| 81 | 112 546 | 112 122 | 82 588 | 1.36 | 19.72 |

In order to support our validation of Swift, a different and larger genome was analysed. A lane of data from 3 Mb of exonic regions in PGP2 (Zaranek,A. et al. (2009) Lessons from the initial data release of the personal genome project, in preparation.) was used for this purpose. This dataset is available online via Tranche at http://openwetware.org/wiki/PGP_and_Tranche. Analysis was performed in a virtual machine on the Free Factories compute infrastructure (Zaranek et al., 2008).

Table 3 summaries our results. Swift produced significantly more reads than the GAPipeline (∼ 106 additional reads). However, fewer of these passed purity filtering, resulting in a smaller total dataset (GAPipeline 502 872 additional reads). The error rate was comparable (GAPipeline 0.3766%, Swift 0.6524%). In order to determine if the GAPipelines increased read count can be attributed to optical duplicates, we ran processed the GAPipeline intensity files against the Swift basecaller and optical duplicate filter. This removed 209 199 duplicate reads accounting for a significant portion of the difference.

Table 3.

Comparison of Swift and the GAPipeline 1.3.2 for a lane of data from 3 Mb of exonic regions in PGP2 (Zaranek,A. et al. (2009) Lessons from the initial data release of the personal genome project, in preparation.)

| Tool | Total reads | PF reads |

|---|---|---|

| Swift | 8 164 716 | 4 665 259 |

| GAPipeline 1.3.2 | 6 903 576 | 5 168 131 |

| GAPipeline 1.3.2+Swift | 6 694 377 | 4 954 683 |

For Swift, ‘total reads’ indicates the number of reads after duplicate filtering.

We have validated Swift for use with genomic data. However, the application of Solexa sequencing to RNA-Seq, Chip-Seq and other sequencing applications are of significant importance. The ability to tune Swift's parameters to lower the optical duplicate rate may be attractive here. Swift supports paired end runs, this does not change the analysis but simply splits reads after they have been generated.

3.1 An assessment of quality scores

As previously described, Swift generates a set of four probabilities at each position. This is calculated as a fraction of the base intensity over the sum of all intensities. For example, probability of an A call would be:

| (2) |

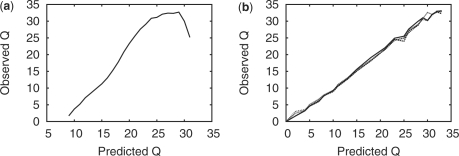

In order to generate a single quality score, Swift extracts the base with the highest probability. This value is scaled over the range of Q6–Q30, such that Q30 represents a probability of one and Q6 zero. Figure 7a shows the observed versus predicted quality scores for one tile of our dataset. As can be seen, the dependence of the observed quality is not linear to those predicted, and they do not reflect the true quality, as to be expected from an uncalibrated quality score. In order to correct for this, we apply a simple calibration (Ewing and Green, 1998) scheme. To generate a calibration table, reads from a training tile are aligned to a reference, those reads with more than seven mismatches are discarded as being most likely generated from contamination. Once the observed quality scores have been calculated, they are used to construct a mapping from predicted to observed values. This mapping may then be applied to another dataset where the true reference may not be known, using a simple lookup table. Figure 7b shows the results of applying this mapping onto a different tile from the same run, the quality scores now largely reflect the true base quality (showing that the method is somewhat transferable). The highest quality assigned is Q32, with 53% of bases being calibrated to Q30 or above. This result shows that the calibration table generated is transferable between tiles. This robust and simple calibration scheme is therefore a reasonable placeholder until more precise methods are developed.

Fig. 7.

(a) Predicted versus observed quality for run 1851 lane 4 tile 1. In calculating this plot reads with more than seven mismatches were discarded in order to remove sample contamination. (b) The data shown in (a) were used to generate a calibration table. This table was then applied to the remaining tiles (21, 41, 61 and 81). The result is that quality scores now largely reflect true quality.

3.2 Computational requirements

Processing a single GA2 tile across 37 cycles requires ∼1 GB of main memory. When compiled using the Intel C++ compiler version 11, processing took 25 min. The GAPipeline uses GNU C++ and modifying this is non-trivial. The GAPipeline took 23 min to process this tile and 657 MB of memory on our dataset (gcc version 4.2.3 installed). Using this compiler Swift took 30 min. Swift however operates on the tile level; a user may therefore submit 800 jobs and gain maximum utilization of their cluster (as opposed to eight jobs which may be submitted for the GAPipeline). Our benchmarks were performed on a single core of a Intel Core2Duo T8100 at 2.10 GHz.

4 DISCUSSION

We have described a new open source pipeline for the analysis of primary data from the Illumina Solexa sequencing platform. Our analysis provides validation of the vendor-provided analysis tools and is the first openly documented technique for extracting sequence data from images on this platform. We have provided a pipeline which other researchers may use as a platform for further development and which allows them to freely distribute their modifications.

Swift protects the user from potentially undesirable changes to the vendor-supplied analysis tools. It gives users an alternative to bundled analysis platforms and allows them to manage their own IT infrastructure. It also provides an openly documented analysis tool enabling the user to understand the primary data, and to investigate frequent device changes which can cause unexpected side effects. For example, the original version of the Genome Analyzer did not image the flowcell wall, current revisions do resulting in artificial poly A sequences. Understanding the primary data is critical to the operation of a high-throughput sequencing facility.

We have also shown that there is significant room for improvement in the vendor-supplied analysis showing an increased yield of 13.6% (at the same error rate). We believe that the image analysis methods presented should prove to be transferable to other next-generation sequencing platforms, such as the Applied Biosciences SOLiD™ Sequencer and Roche 454 FLX, though in the latter case, the image analysis problem should be simplified due to the regular arraying of beads. Potentially, this allows a user to maintain a single primary data analysis platform for all second generation systems.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the following individuals from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute: James Bonfield for many illuminating discussions, Andy Brown and Roger Pettett for their suggestions relating to Swift's reporting module and Tony Cox for his continued support. We also thank Klaus Maisinger of Illumina for discussions relating to the Illumina primary data analysis methods and Tony Cox of Illumina for answering our queries relating to PhageAlign.

Conflict of Interest: Since the inception of this work Nava Whiteford and Clive Brown have moved to 3rd Generation sequencing company, Oxford Nanopore Technologies. The other authors have declared none.

REFERENCES

- Bentley D, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CG, et al. Solexa/Illumina GAPipeline product and product documentation. Illumina Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Castro ED, Morandi C. Registration of translated and rotated images using finite fourier transforms. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1987;9:700–703. doi: 10.1109/tpami.1987.4767966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope LM, et al. A benchmark for Affymetrix genechip expression measures. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:323–331. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlich Y, et al. Alta-cyclic: a self-optimizing base caller for next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:679–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. ii. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigo M, Johnson SG. FFTW: An Adaptive Software Architecture for the FFT. In: Frigo M, Johnson SG, editors. Proceedings of ICASSP 3. IEEE; 1998. pp. 1381–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway A, et al. Statistical analysis of an rna titration series evaluates microarray precision and sensitivity on a whole-array basis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Speed T. An estimate of the crosstalk matrix in four-dye fluorescence-based DNA sequencing. Electrophoresis. 1998;20:1433–1442. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990601)20:7<1433::AID-ELPS1433>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, et al. Validation and extension of an empirical Bayes method for SNP calling on Affymetrix microarrays. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R63. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-r63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail M, et al. A large genome center's improvements to the Illumina sequencing system. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, et al. A comparison of background correction methods for two-colour microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2700–2707. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougemont J, et al. Probabilistic base calling of Solexa sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra J. Image Analysis and Mathematical Morphology. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zaranek AW, et al. ATC'08: USENIX 2008 Annual Technical Conference on Annual Technical Conference. Berkeley, CA: USENIX Association; 2008. Free factories: unified infrastructure for data intensive web services; pp. 391–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.