Abstract

The production of disease-targeted agents requires the covalent conjugation of a targeting molecule with a contrast agent or therapeutic, followed by purification of the product to homogeneity. Typical targeting molecules, such as small molecules and peptides, often have high charge to mass ratios and/or hydrophobicity. Contrast agents and therapeutics themselves are also diverse, and include lanthanide chelates for MRI, 99mTc chelates for SPECT, 90Y chelates for radiotherapy, 18F derivatives for PET, and heptamethine indocyanines for near-infrared fluorescent optical imaging. We have constructed a general-purpose HPLC/mass spectrometry platform capable of purifying virtually any targeted agent for any modality. The analytical sub-system is composed of a single dual-head pump that directs mobile phase to either a hot cell for the purification of radioactive agents or to an ES-TOF MS for the purification of nonradioactive agents. Nonradioactive agents are also monitored during purification by ELSD, absorbance, and fluorescence. The preparative sub-system is composed of columns and procedures that permit rapid scaling from the analytical system. To demonstrate the platform's utility, we describe the preparation of five small molecule derivatives specific for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA): a gadolinium derivative for MRI, indium, rhenium, and technetium derivatives for SPECT, and a yttrium derivative for radiotherapy. All five compounds are derived from a highly anionic targeting ligand engineered to have a single nucleophile for N-hydroxysuccinimide-based conjugation. We also describe optimized column/mobile phase combinations and mass spectrometry settings for each class of agent, and discuss strategies for purifying molecules with extreme charge and/or hydrophobicity. Taken together, our study should expedite the development of disease-targeted, multimodality diagnostic and therapeutic agents.

Keywords: High-performance liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, multimodality contrast agents, targeted therapeutics, diagnostic contrast agents, radiotherapeutics, magnetic resonance imaging, prostate-specific membrane antigen

INTRODUCTION

The ultimate success of molecular imaging will hinge on the development of targeted diagnostic agents. Some clinical applications, such as stem cell tracking, will require agents specific for normal cells, tissues, or organs, while others, such as cancer-detection, will require specificity for diseased cells, tissues, or organs. The future treatment of most diseases will also require molecular targeting. Low-molecular weight ligands, such as small molecules and peptides are highly preferred for disease targeting due to their rapid biodistribution, rapid clearance, and improved tissue/tumor penetration.

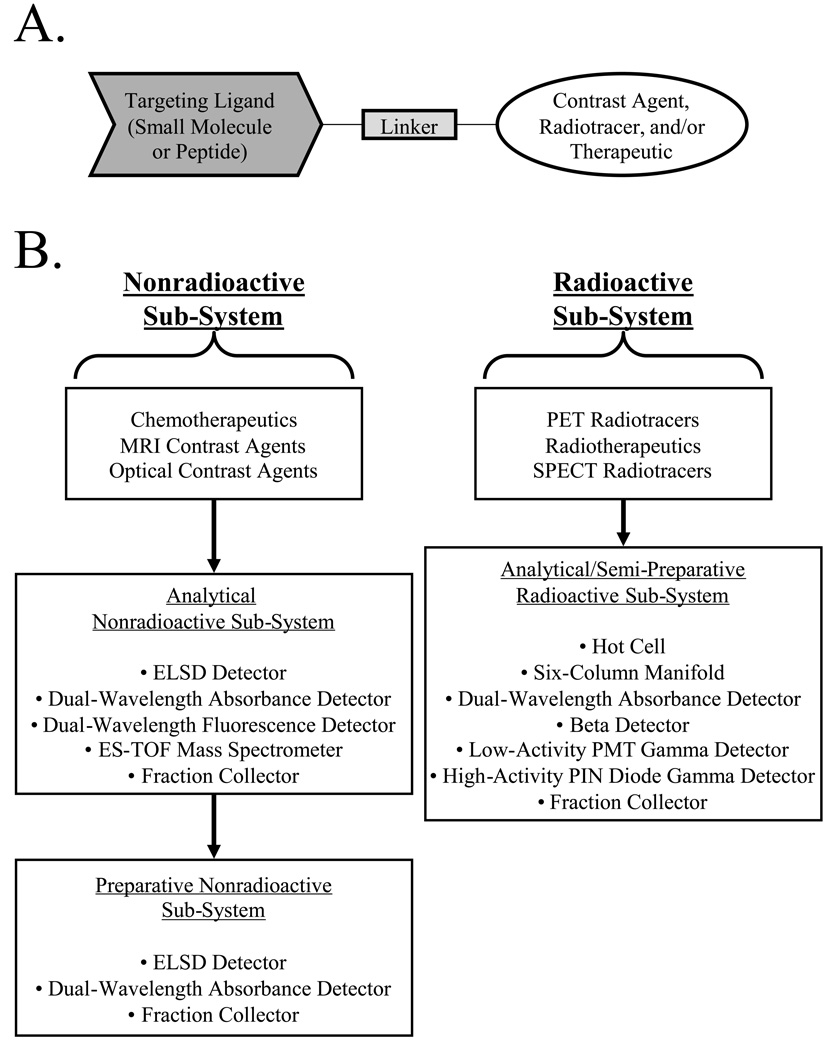

Inherent to both diagnostic and therapeutic clinical applications is the need to create bifunctional molecules that are composed of a targeting domain and a "functional" domain, typically joined together with an appropriate linker (Figure 1A). The benefits of a "modular" approach to targeted agents are numerous. For example, both the targeting molecule and functional molecule, e.g., contrast agent, radiotracer, chemotherapeutic, etc. can be optimized separately. Hence, one targeting molecule can potentially be used with many different functional molecules. If the linker is chosen appropriately, the targeting and functional domains will be truly "isolated", thus retaining their optimized properties. However, there are also problems with the modular approach. Small molecules and peptides that exhibit high specificity and affinity for in vivo targets often have high charge and/or hydrophobicity, making purification of final bifunctional molecules difficult and time-consuming. If agents for multiple modalities are desired, the number of reactants and products can be large, with each set requiring its own optimization.

Figure 1.

Overview of the LC/MS platform for the development of disease-targeted agents.

A) A typical disease-targeted agent is created from the covalent conjugation of a small molecule or peptide targeting ligand to a functional molecule, through an appropriate linker.

B) Depending on the type of desired agent, one of three different platform sub-systems are utilized for molecule preparation, with the major components of each sub-system shown.

C) Switching between nonradioactive and radioactive sub-systems is accomplished using a master valve directing pump flow and two electrical switchboxes as shown.

Recently, we described a family of highly anionic small molecules specific for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA [1]). PSMA is a 100 kDa type II transmembrane glycoprotein whose expression in the systemic circulation is abundant in, and highly restricted to, normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. Prostate cancer is in special need of targeted diagnostic and therapeutic agents, since in 2005 alone, an estimated 30,350 men have died of the disease [2]. As prostate cancer evolves to a hormone refractory state, both levels of PSMA and the ratio of the major (transmembrane) splice variant to the minor (cytosolic) splice variant, greatly increase [3], making it a highly desirable target for bifunctional agents [4–9].

To overcome barriers associated with developing disease-specific, targeted agents, we have developed a general purpose HPLC/mass spectrometry platform that permits virtually any bifunctional molecule to be purified to homogeneity and fully characterized. Using PSMA-specific small molecules as examples, we demonstrate the development of agents for MRI imaging, SPECT imaging, and radiotherapy, and demonstrate their bioactivity with living prostate cancer cells.

RESULTS

Platform Overview

Disease-targeted diagnostic and therapeutic agents include nonradioactive molecules such as chemotherapeutics, MRI contrast agents, and optical contrast agents, as well as radioactive agents such as PET radiotracers, SPECT radiotracers, and β-emitting radiotherapeutics. As such, the platform we have developed has sub-systems for the purification of these two general classes of molecules, with the major components of each sub-system shown in Figure 1B. To conserve space, minimize cost, and maximize reproducibility, the two analytical sub-systems (nonradioactive and radioactive) are constructed adjacent to each other, and share a common binary pump (model 1525 binary pump, Waters, Milford, MA) and in-line degasser (Waters), with switching between the two systems accomplished using a master valve (model 7030, Rheodyne, Rohnert Park, CA) to direct solvent flow, and two switchboxes to direct electrical connections (Figure 1C). A summary of recommended columns and mobile phases for the platform is provided in Table I.

Table I.

Recommended Column and Mobile Phase Combinations

| Type | Column Name |

Pore Size |

Particle Size |

Manufacturer | Catalog # | Overall Size |

Capacity | Recommended Mobile Phases (A/B) |

Recommended Flow Rate (ml/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anion-Exchange (Analytical) | Protein-Pak | 1000 Å | 10 µm | Waters | WAT088044 | 7.5 × 75 mm | 10 mg | H2O/NH4 + Formate* | 1 |

| C4 (Analytical) | Delta-Pak | 100 Å | 5 µm | Waters | WAT011796 | 3.9 × 150 mm | 6 mg | TEAA/CH3CN | 1 |

| C4 (Preparative) | Delta-Pak | 100 Å | 15 µm | Waters | WAT011809 | 19 × 300 mm | 270 mg | TEAA/CH3CN | 15 |

| C18 (Analytical) | Symmetry | 100 Å | 5 µm | Waters | WAT045905 | 4.6 × 150 mm | 8 mg | TEAA/MeOH | 1 |

| C18 (Preparative) | Symmetry | 100 Å | 7 µm | Waters | WAT066240 | 19 × 150 mm | 135 mg | TEAA/MeOH | 15 |

| C18 (Preparative) | Symmetry | 100 Å | 7 µm | Waters | WAT066245 | 19 × 300 mm | 270 mg | TEAA/MeOH | 15 |

| Gel-Filtration (Analytical) | YMC-Pack | 60 Å | 5 µm | YMC | DL06S053008WT | 8 × 300 mm | 10 mg | PBS | 1 |

| Gel-Filtration (Analytical) | YMC-Pack | 200 Å | 5 µm | YMC | DL20S053008WT | 8 × 300 mm | 10 mg | PBS | 1 |

| Gel-Filtration (Preparative) | Ultrastyragel | 1000 Å | 7 µm | Waters | Custom | 19 × 300 mm | 20 mg | PBS | 5 |

| Silica (Preparative) | Nova-Pak | 60 Å | 6 µm | Waters | WAT038501 | 3.9 × 300 mm | 12 mg | Various | 1 |

High concentrations of NH4 + Formate result in refractive inde× changes that will saturate the absorbance detector

Analytical HPLC/MS Sub-System for Nonradioactive Molecules

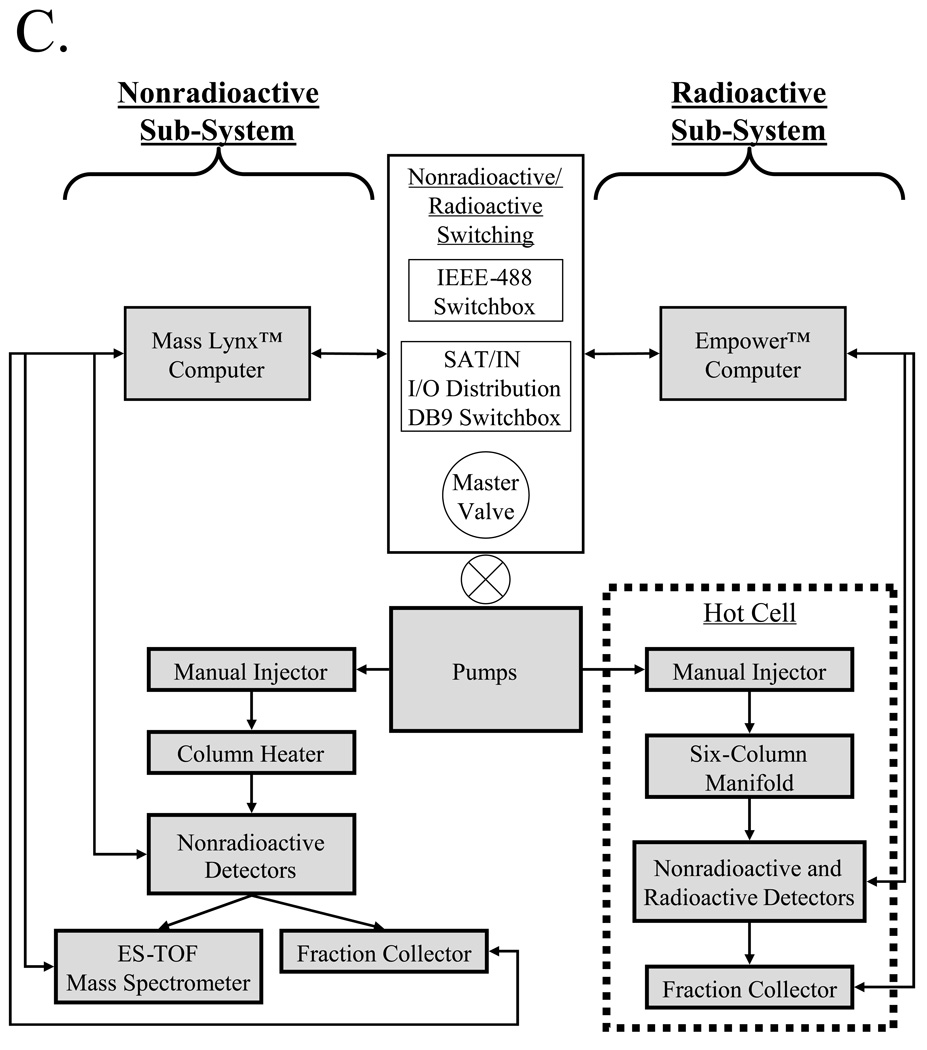

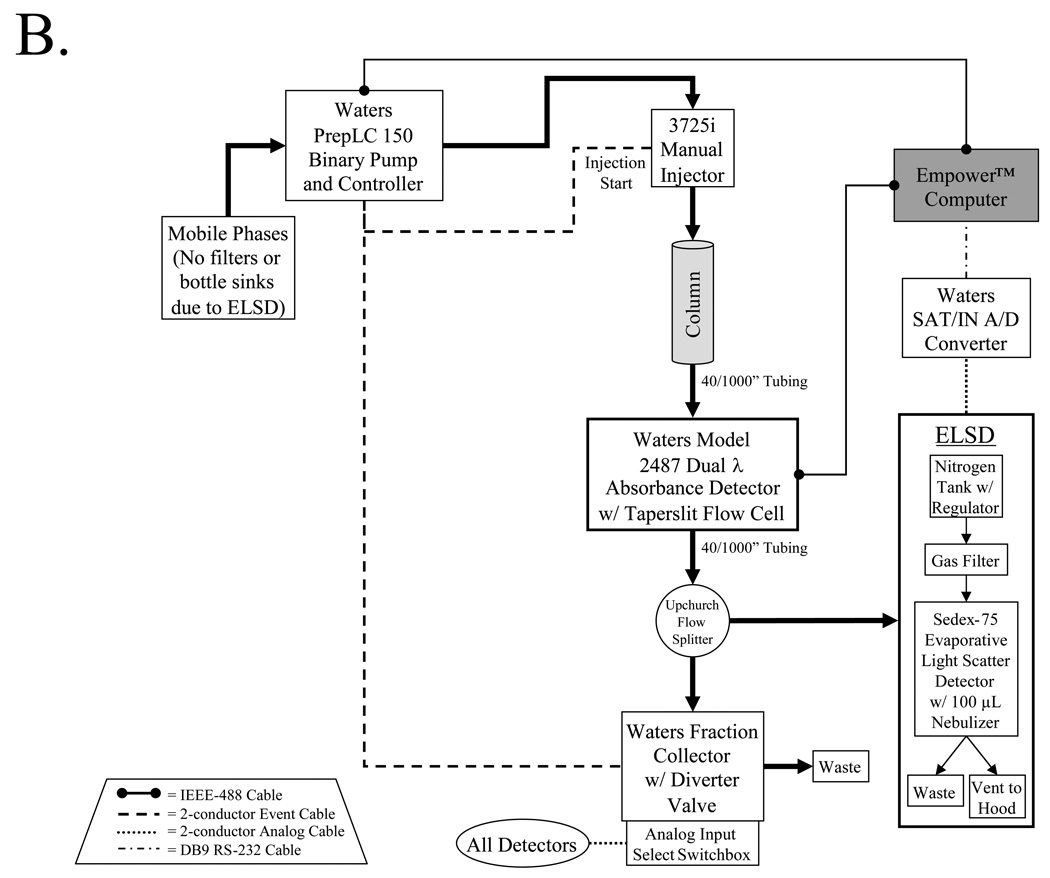

The plumbing and electrical connections of the nonradioactive analytical sub-system is detailed in Figure 2A. From the master valve, solvents flow through the desired temperature-controlled column to the absorbance (Waters 2487) and fluorescence (Waters 2475) detectors. The Waters 2487 dual λ absorbance detector is a two-channel, tunable, ultraviolet/visible detector. It operates from 190 to 700 nm and monitors absorbance at one or two discrete wavelengths. The Waters 2475 multi λ fluorescence detector is a multi-channel, tunable, fluorescence detector designed for HPLC applications. It operates from 200 to 900 nm and monitors fluorescence at one or two discrete wavelength pairs. Smaller diameter tubing (9/1000") is used after the column to prevent the formation of cavitation bubbles and band broadening. Using a flow-splitter (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA) a small fraction (typically 10–20%) of the flow is directed to an evaporative light scatter detector (ELSD). The ELSD is the heart of the system, and is capable of detecting high pg to low ng amounts of any non-volatile compound eluting from the column (even salts). Indeed, the ELSD is so sensitive that standard bottle sinks and filters cannot be used on the system, since leaching of trace compounds from these devices will saturate the ELSD. Special care must also be taken with solvents, since even many "HPLC grade" solvents have impurities detected by ELSD. The ELSD in our platform is equipped with a special low-flow nebulizer (Richards Scientific, Novato, CA) that reduces band-broadening at low flow rates, with total flow rates limited to 1 ml/min.

Figure 2.

Nonradioactive analytical and preparative sub-systems. Thick black arrows indicate the path, and direction, of fluid flow. Electrical connections are as indicated in the trapezoidal legends.

A) The analytical sub-system is composed of detectors for all non-volatile compounds (ELSD), photon-absorbing compounds (dual-channel absorbance detector), fluorescent compounds (dual-channel fluorescent detector), and mass verification (ES-TOF mass spectrometer).

B) The preparative sub-system includes high-flow pumps, an ELSD and dual-channel absorbance detectors.

The remainder of the eluate is split again between a Waters Micromass LCT TOF-ES mass spectrometer (Waters) equipped with a LockSpray exact mass ionization source, and a fraction collector equipped with a waste diverter valve. A custom switchbox controls the analog input to the fraction collector so that it can be triggered from any of the detectors. Output from all four detectors, as well as fraction collector events, are acquired simultaneously using MassLynx™ (Waters) software and stored on a PC. Although not shown in Figure 2A, an additional configuration of the system permits Empower™ (Waters) software to control all functions of the system except the mass spectrometer.

The mass spectrometer uses electrospray ionization, which is a very “soft” ionization technique that is compatible with even sensitive non-covalent biomacromolecular complexes. There is virtually no limit to the size of molecules that can be ionized and detected, and the spectrometer interfaces easily with HPLC separation techniques [10]. The mass analyzer utilizes time-of-flight (TOF), which separates ions according to their velocity, with ions of the highest mass to charge ratio (m/z) arriving later in the spectrum. Unlike scanning instruments, the TOF performs parallel detection of all masses within the spectrum at very high sensitivity and acquisition rates. This characteristic is of particular advantage when the instrument is coupled to a HPLC, since each spectrum is representative of the sample composition at that point in time, irrespective of how rapidly the sample composition is changing. TOF also has several advantages over the quadrupole, the most widely used mass analyzer [10]. Mass resolution (m/z) is in thousands for TOF whereas quadrupole detection is limited to 300 to 4000, depending on the physical parameters of the spectrometer. Finally, TOF offers mass accuracy in tens of parts per million (ppm), whereas quadrupole accuracy is in hundreds of ppm.

Preparative HPLC Sub-System for Nonradioactive Molecules

The preparative chromatography system consists of a Prep LC 150 ml fluid handling unit (Waters) equipped with a manual injector (Rheodyne 3725i) and a 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector (Waters) outfitted with a semi-preparative flow cell. An Upchurch flow splitter then diverts a portion of the eluate to an ELSD detector equipped with the same low-flow nebulizer as the analytical sub-system while the other portion is directed into a fraction collector.

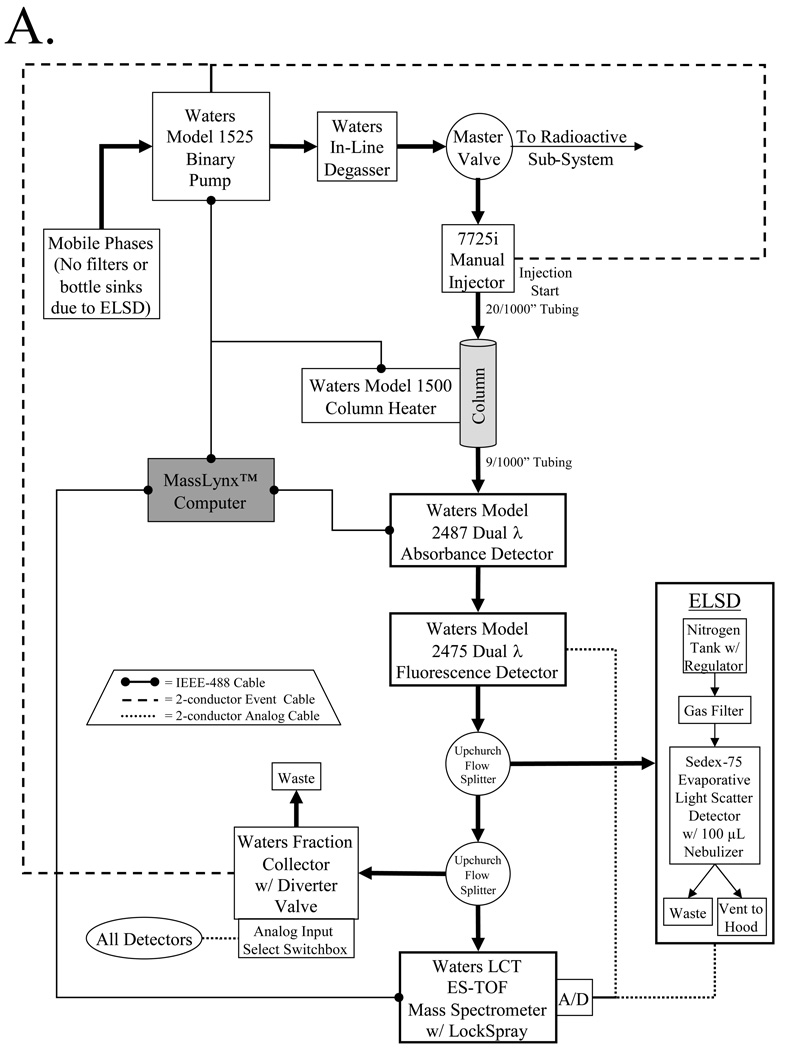

HPLC Sub-System for Radioactive Molecules

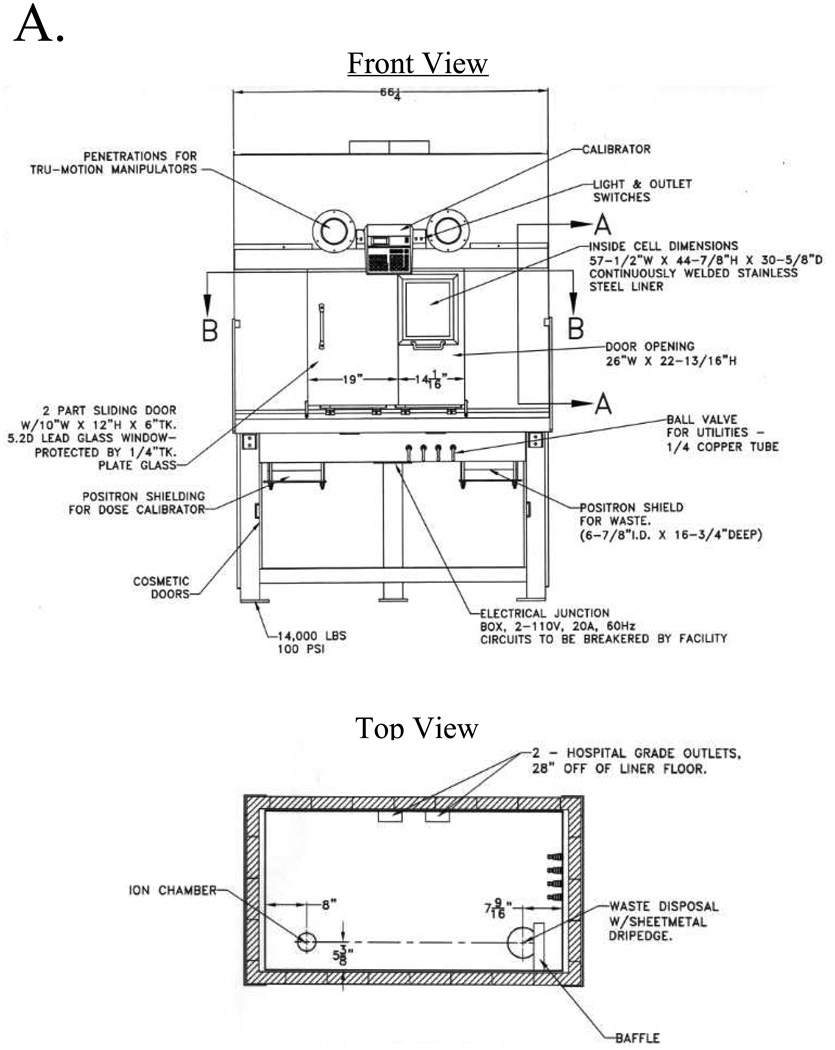

With the master valve and electrical switchboxes set to the radioactive sub-system, solvent flow is directed into the custom hot cell, which permits the safe use of medium- (e.g., SPECT) and high-energy (e.g., PET) radioisotopes (Figure 3A). All plumbing and electrical connections into, and out of, the hot cell are through a 33/8" diameter lead-baffled port on its right side. The hot cell is equipped with special features including an integrated dose calibrator and a shielded waste bottle holder, both mounted below bench level to maximize interior available space. It is also equipped with external control valves for gas, water, air, and vacuum, and internal AC electrical sockets.

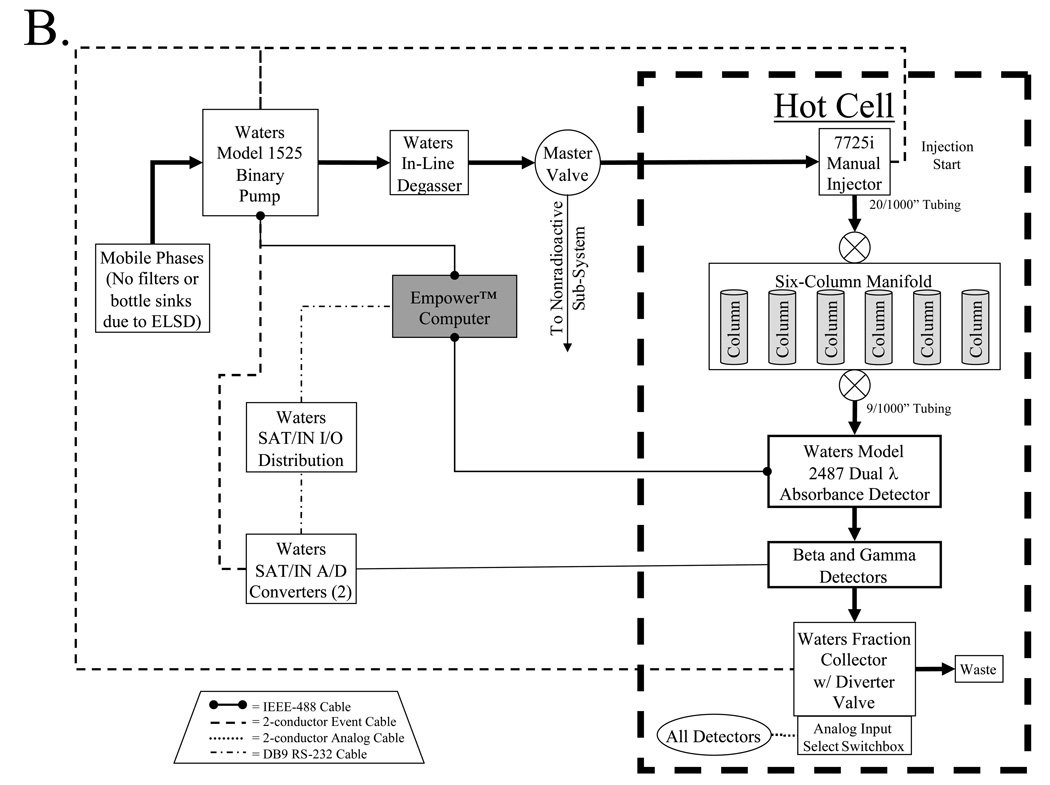

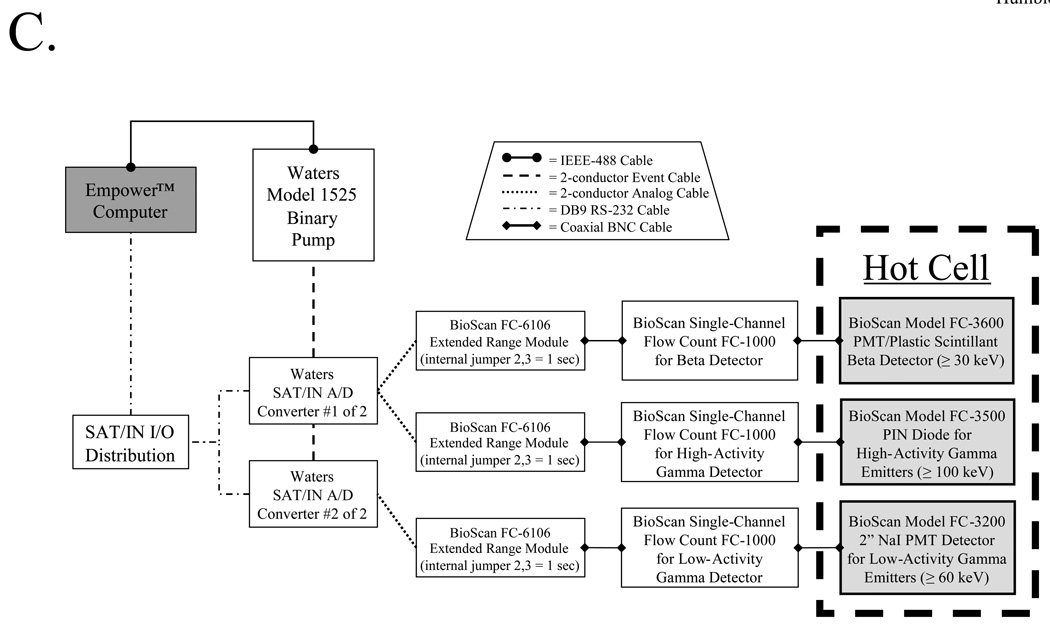

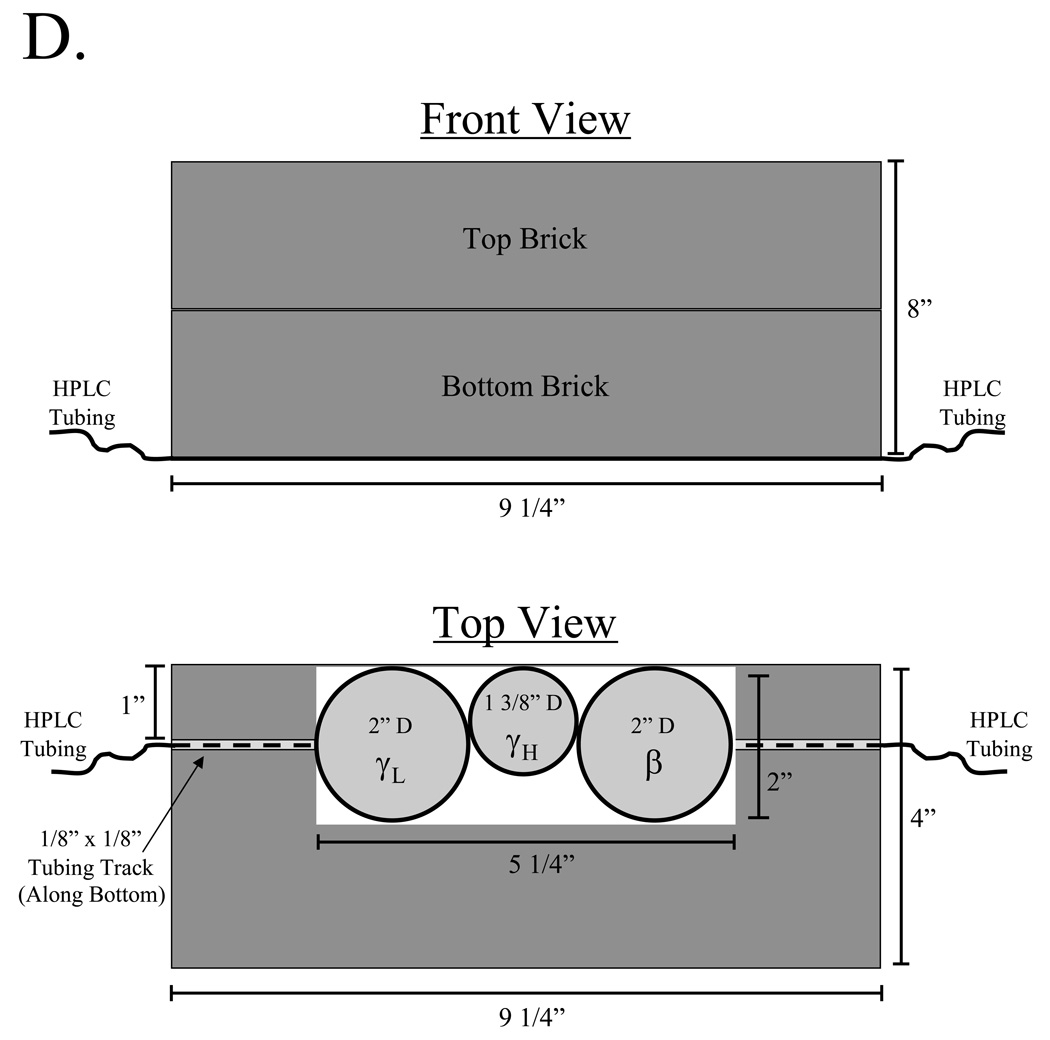

Figure 3.

Radioactive sub-system. Thick black arrows indicate the path, and direction, of fluid flow. Electrical connections are as indicated in the trapezoidal legends.

A) Detailed schematic for the custom hot cell shown in front view (top) and top view (bottom). Plumbing and electrical wires enter through a 3 3/8" diameter leaded baffle on the right side. A fully-shielded dose calibrator (left) and waste container (right) are integrated into the hot cell, and are mounted below bench level to minimize loss of space. External ball valves control internal water, gas, air, and vacuum quick-disconnect lines.

B) After sample loop injection, the entire purification process of the radioactive sub-system is automated under computer control. Sub-system detectors include dual-channel absorbance, beta decay, low-activity gamma decay, and high-activity gamma decay.

C) Radiation detectors and their associated electronics are shown, along with interfacing to the data acquisition computer.

D) The three radiation detectors (γL = low-activity gamma PMT, β = beta, γH = high-activity gamma PIN diode) are mounted in a custom lead enclosure comprised of two lead bricks, which prevents general hot cell contents from triggering detectors. HPLC tubing runs along a track cut into the bottom brick as shown.

An overview of the radioactive sub-system is shown in Figure 3B. After sample injection, solvent flow is directed to one of six columns via a custom manifold. Eluate then passes through a dual-channel absorbance detector (Waters model 2487) and a series of radiation detectors before either being collected or disposed. Radiation detectors include those for beta counting (≥ 30 keV), low- to medium-energy (≥ 60 keV) low-activity (µCi range) gamma counting, and medium- to high-energy (≥ 100 keV) high-activity (mCi-Ci range) gamma counting, with their associated electronics (Figure 3C). The detectors are mounted in a custom lead enclosure (Figure 3D), which shields the detectors from other contents of the hot cell.

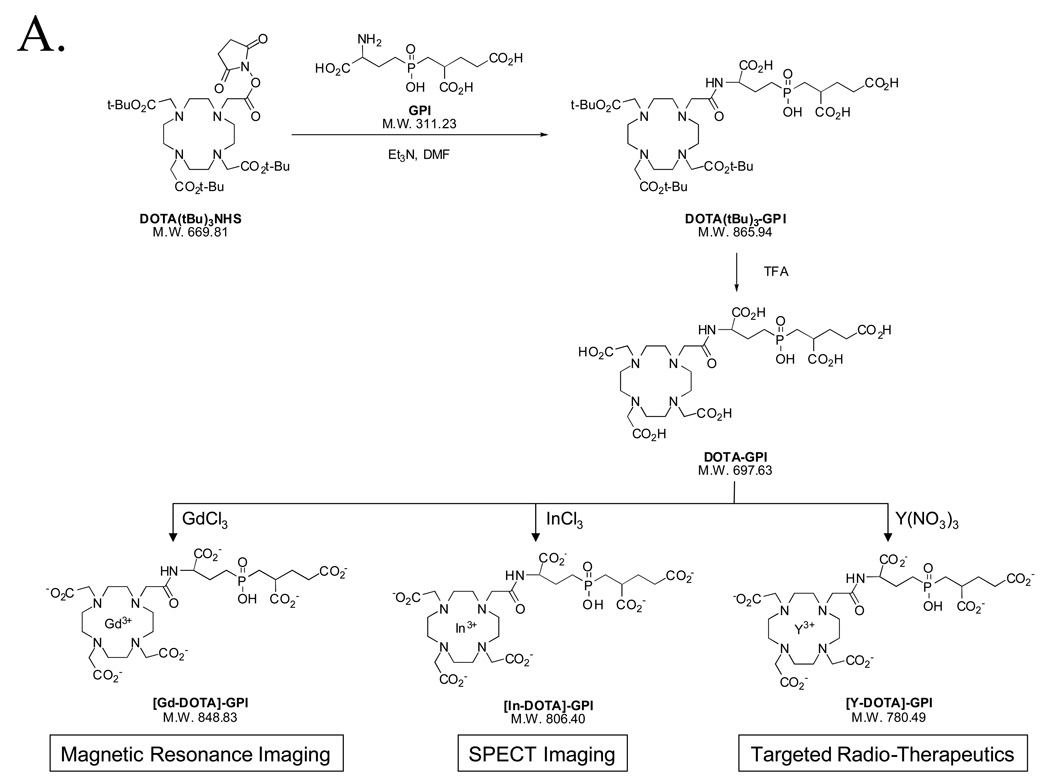

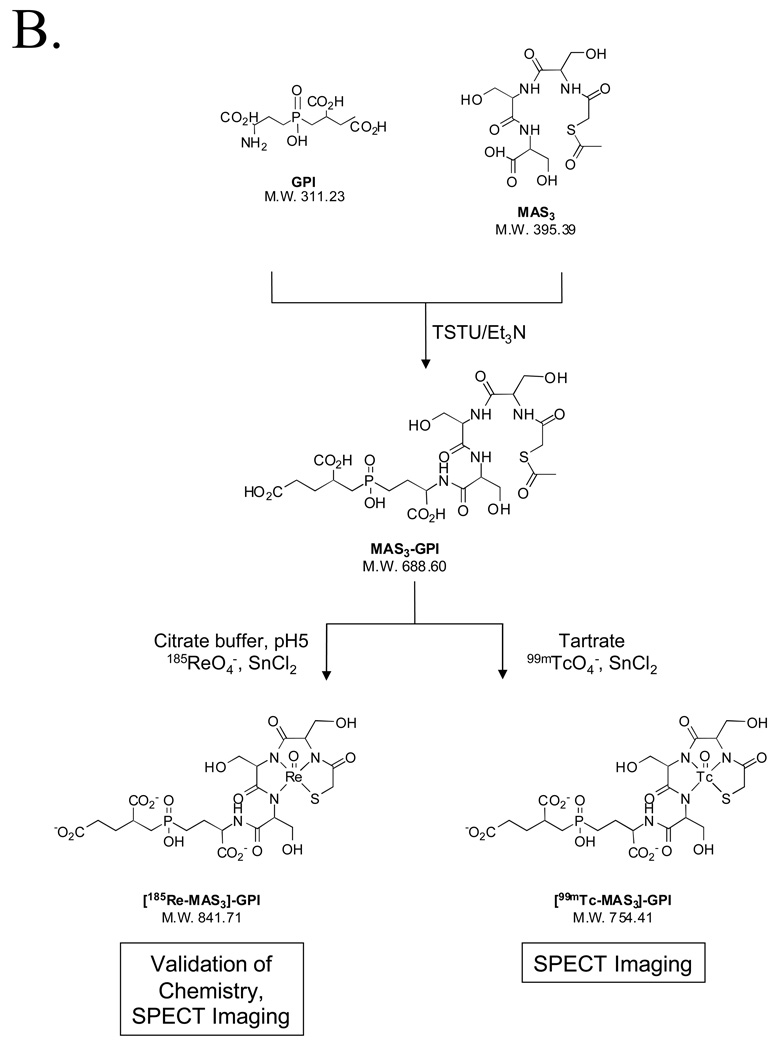

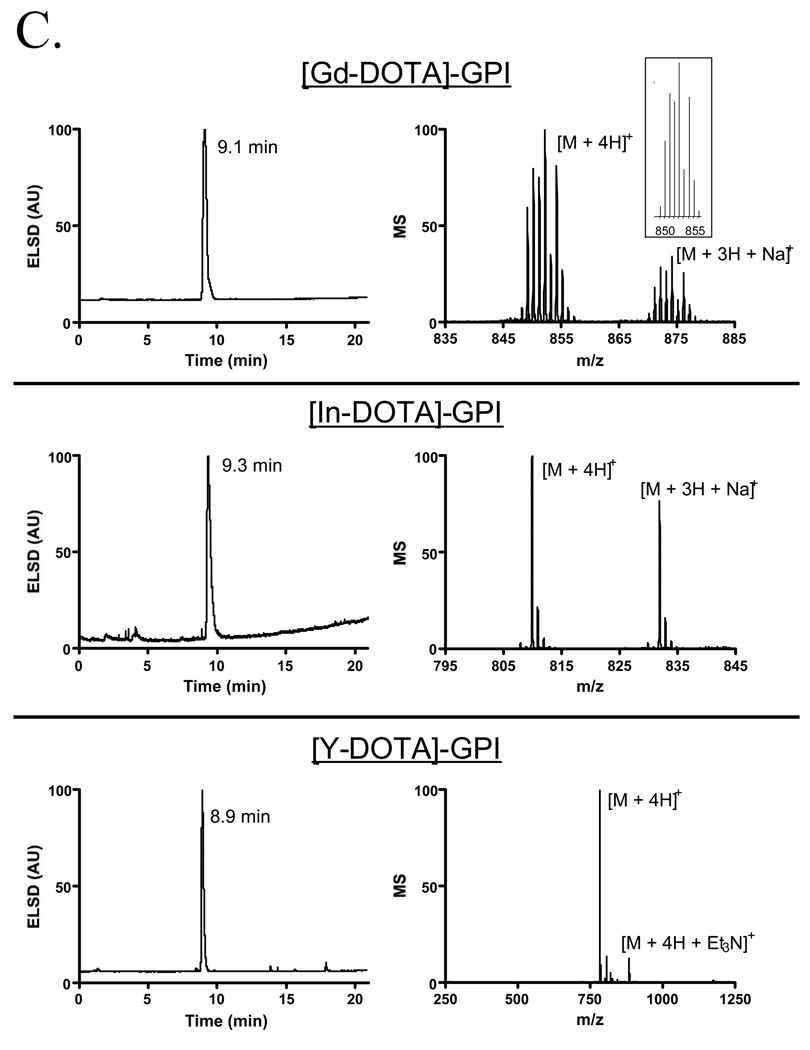

Preparation and Purification of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Targeted Diagnostic and Therapeutic Agents

To demonstrate the utility of the purification platform described above, we focused on a family of highly anionic PSMA-specific small molecules described previously by our group [1]. The GPI molecule, in particular, is especially difficult to work with since it has three carboxylic acids and a phosphinic acid on a mass of only 311 Da, leading to a high mass to charge ratio (Table II). Having been engineered to contain a single nucleophile (free amine) for conjugation, GPI was used as the targeting ligand to create agents for MR imaging (Gd chelate), SPECT imaging (In, Re, and Tc chelates), and therapy (Y chelate) using the chemistry shown in Figures 4A and 4B. Conjugation, analytical separation, and preparative purification were performed as described in the Experimental section. Validation of the final purified products is shown in Figure 4C (Gd, In, Y chelates) and Figure 4D (Re and Tc chelates), and is summarized in Table II. Note that in these proof of principle experiments, nonradioactive In, Re, and Y isotopes were used, although no difference in technique for the radioactive versions is anticipated. Note also that Re derivatives require different HPLC and MS conditions for optimal detection (Figure 4D and Table II).

Table II.

Small Molecule Derivatives Specific for Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen

| Molecule | Type | Modality | Expected M.W. |

Found M.W. |

Net Charge |

Charge to Mass Ratio (X 10−3) |

Column | Mobile Phase (A/B) |

Mass Spec Mode |

Capillary Voltage |

Cone Voltage |

Live Cell Binding Affinity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPI | Targeting | n/a | 311.23 | 310.45 | −3 | −9.6 | n/a | n/a | Neg | −3000V | −30V | 9.0 nM |

| [Gd-DOTA]-GPI | Diagnostic | MRI | 851.85 | 852.31 | −4 | −4.7 | SC18A | TEAA/MeOH | Pos | 3300V | 40V | 29.0 nM |

| SC18P | TEAA/MEOH | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||||||

| [In-DOTA]-GPI | Diagnostic | SPECT | 809.42 | 810.35 | −4 | −4.9 | SC18A | TEAA/MeOH | Pos | 3300V | 40V | 22.3 nM |

| [99mTc-MAS3]-GPI | Diagnostic | SPECT | 743.07 | n/a | −4 | −5.3 | SC18A | TEAA/MeOH | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| [Re-MAS3]-GPI | Diagnostic | SPECT | 844.73 | 842.95 | −4 | −4.7 | SC18A | H2O/CH3CN+0.1% FA | Neg | −3300V | −30V | 34.6 nM |

| [Y-DOTA]-GPI | Therapeutic | Radiotherapy | 783.51 | 784.21 | −4 | −5.1 | SC18A | TEAA/MeOH | Pos | 3300V | 40V | 12.7 nM |

Columns: SC18A = Symmetry C18 4.6 × 150 mm (Analytical); SC18P = Symmetry C18 19 × 300 mm (Preparative) FA = Formic acid

Live cell binding assays were performed in TBS, pH 7.4. The mean ± S.D. affinity from N = 3 independent experiments is shown

Figure 4.

Diagnostic and therapeutic agents targeted to prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA).

A) Chemical structures, conjugation chemistry, and chelate loading of PSMA-specific DOTA chelates.

B) Chemical structures, conjugation chemistry, and chelate loading of PSMA-specific MAS3 chelates.

C) Platform-purification of nonradioactive PSMA-specific targeted agents. Shown is the ELSD tracing, mass spectrometry of the peak fraction, and the predicted isotopic pattern for those molecules with an isotopic distribution (inset).

D) Platform-purification of radioactive PSMA-specific targeted agents. Shown at the top is the ELSD tracing, mass spectrometry of peak fraction, and predicted isotopic pattern for the 185Re derivative of MAS3-GPI. Shown at the bottom are the low-activity gamma detector tracings for 99mTcO4 − prior to loading onto MAS3-GPI, and [99mTc-MAS3]-GPI after loading and purification.

Bioactivity of PSMA-Targeted Diagnostic Agents

The binding assay described in the Experimental section was used to measure the binding affinity of each purified agent on living prostate cancer cells. The results, shown in Table II, confirm that GPI conjugates have affinity in the nM range, which is consistent with previously published reports of GPI conjugated to NIR fluorophores [1].

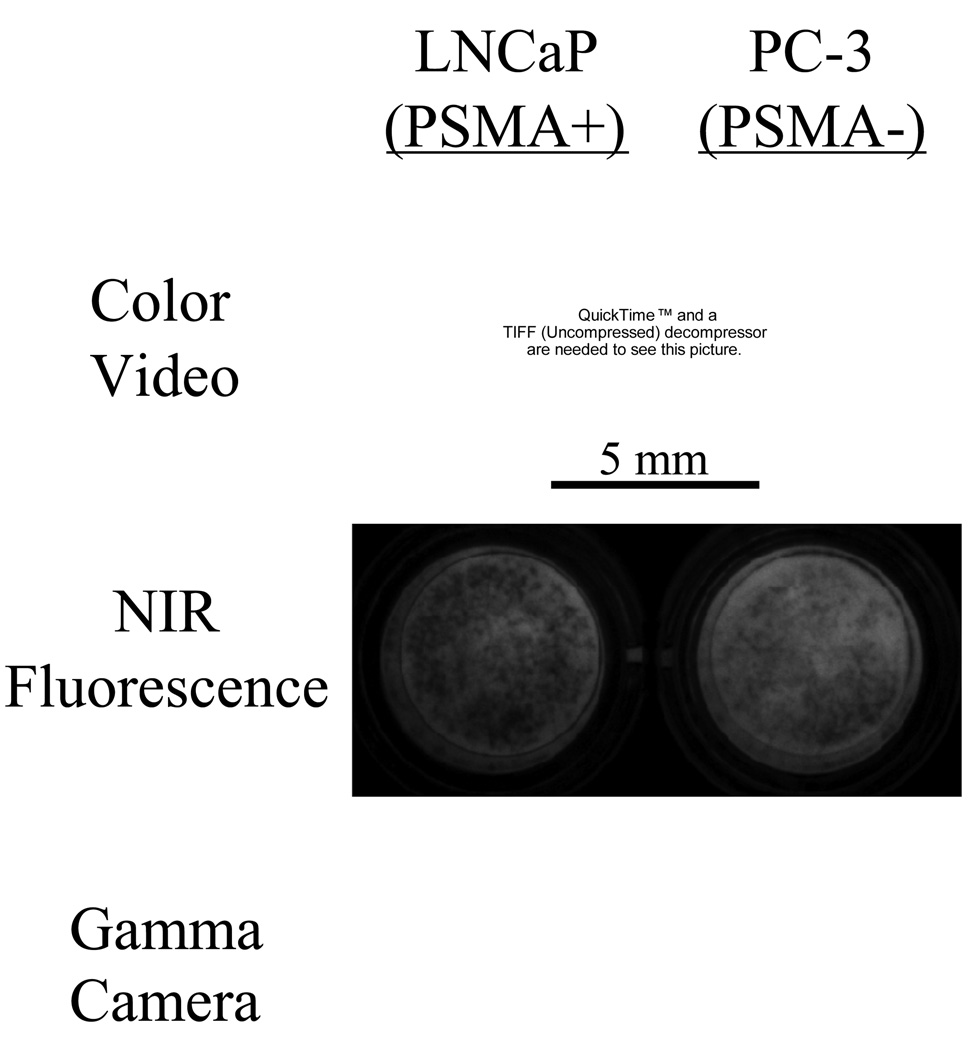

To demonstrate that molecules purified on the platform are competent for use as diagnostic agents, radioscintigraphic imaging was performed. As shown in Figure 5, living PSMA-expressing prostate cancer cells, but not non-expressing cells, showed intense binding of [99mTc-MAS3]-GPI to their surface.

Figure 5.

Bioactivity of diagnostic agents targeted to prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). Live cell binding of [99mTc-MAS3]-GPI in TBS for 20 min at 4°C onto PSMA-positive LNCaP cells (left) and PSMA-negative PC-3 cells (right), followed by extensive washing with TBS. Cells were independently loaded with NIR fluorophore IR-786 to assess viability and confluence. Shown are the color video, NIR fluorescence, and gamma detector images of cells grown on 96-well filter plates.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we present a streamlined approach for the development of targeted diagnostic and therapeutic agents. First, the small molecule or peptide targeting ligand is engineered to contain a single nucleophile for conjugation, and is optimized for binding affinity and physicochemical properties independent of the desired functional molecule. Second, the functional molecule is conjugated covalently to the targeting ligand with a linker that provides adequate "isolation" of the two functions. Third, simple NHS ester chemistry is used for conjugation since it is fast, efficient, has few side reactions, and forms a stable amide bond. Finally, the platform described above is used to separate reactants from products and to purify the final desired compound to homogeneity. This strategy makes no assumptions about the final use of the compound, i.e., diagnostic versus therapeutic, and has few limitations with respect to modality, i.e., MR imaging, optical imaging, radioscintigraphic imaging, etc.

The platform we described above integrates nonradioactive and radioactive sub-systems by sharing common pumps and degasser. By so doing, there are savings in bench space and cost, and reproducibility between nonradioactive and radioactive versions of the same molecule is maximized. Considering that the retail cost of the entire platform is approximately $550K, any possible cost savings is important. Of course, if bench space and cost is not an issue, the nonradioactive and radioactive systems can be separated by adding a binary pump and degasser, which will also increase molecule throughput.

An important feature of the platform is its scalability between analytical and preparative scales. First, we have chosen column families (e.g., Delta-Pak C4 and Symmetry C18 columns) that are designed for rapid scaling. Second, all peaks are first identified by ELSD and mass spectrometry on the analytical sub-system prior to preparative scale-up. The ELSD detects every non-volatile eluate (even salts) from the column, so there are no ambiguities or unknown peaks when transferring the process to the preparative sub-system, which is equipped with the same ELSD.

From the examples shown, it appears that ES-TOF mass spectrometry works reasonably well for the identification of small molecules chelated with metals such as gadolinium, indium, yttrium, and rhenium. In truth, metal-chelated compounds fly poorly in the mass spectrometer compared to their non-metal precursors. Although adding significantly to the cost and complexity of the platform, addition of an inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass spectrometer would likely provide much higher sensitivity for metal-containing small molecules.

We presented PSMA-specific small molecules containing Gd for MR imaging, In, Re, and Tc for SPECT imaging, and Y for radiotherapy. As described in detail previously [1], GPI conjugates compete for the active site of the PSMA enzyme with phosphate and other anions. For this reason, our studies were conducted in non-phosphate containing medium. Nevertheless, the affinity of these compounds for the surface of living cells is in the nanomolar range, and specificity is high. Recently developed GPI derivatives (Humblet et al., manuscript in preparation; Misra et al., manuscript in preparation) have restored full binding to living cells in any physiological medium. A second problem not addressed in this study is the post-labeling approach for molecule chelation. GPI is highly anionic and might be expected to chelate the metals used in this study independent of MAS3 or DOTA. To date, we can find no chromatographic or mass spectrometric evidence that this phenomenon occurs (data not shown), but to eliminate it as a possibility, future studies will focus on novel methods for metal pre-labeling. As high affinity, disease-specific molecules such as these continue to evolve, the platform used in this study will ensure rapid purification and characterization.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe an integrated platform of HPLC systems, detectors, columns, mobile phases, and procedures for the production of single- and multimodality disease-targeted diagnostic and therapeutic agents, and demonstrate the performance of these molecules with living prostate cancer cells.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents

HPLC grade triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), pH 7 was from Glen Research (Sterling, VA), HPLC grade water was from American Bioanalytic (Natick, MA), HPLC grade MeOH was from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL) and HPLC grade acetonitrile was from VWR International (West Chester, PA). Formic acid 99% for analysis was purchased from Acros Organic (Geel, Belgium). Guilford 11245-36 (GPI; 2[((3-amino-3-carboxypropyl)(hydroxy)(phosphinyl)-methyl]pentane-1,5-dioic acid) was synthesized as described previously [11]. The perchlorate salt of IR-786 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). DOTA(tBu)3 NHS ester (1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-tris(t-butyl acetate)-10-succinimidyl acetate) was purchased from Macrocyclics (Dallas, TX). Other solvents and chemicals obtained from commercial sources were analytical grade or better and used without further purification.

Mass Spectrometer Technical Specifications and Calibration

The LCT time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) features a ZSpray source with electrospray ionization (ESI), hexapole lenses, and a modular LockSpray™ interface for acquisition of exact mass data. A 1 ng/µL (1:1 CH3CN:H2O) solution of Leucine Enkephalin is infused directly into the LockSpray by means of a syringe pump at a flow rate of 10 µL/min. A 10 ng/μL (MeOH) solution of poly-DL-alanine (Sigma, St-Louis, MO) is used to calibrate the instrument in both positive and negative modes for mass range 100 to 1500. The following solution is used to calibrate the instrument for protein work in positive mode (mass range 600 to 3200): horse heart myoglobin (Sigma) 5 pm/µL and bovine trypsinogen (Sigma) 10 pm/µL in 1:1 CH3CN:H2O + 0.2% formic acid. The mass range of acquisition used for the examples described in this paper was 100 to 1500.

GPI Conjugation and Chelate Loading of Gd, In, and Y

Synthesis of DOTA(tBu)3-GPI

180 µl of pure Et3N was added to a solution of 0.02 g (0.064 mmol) of GPI in 4 ml of DMF. After 5 min, a solution of 0.05 g (0.06 mmol) of DOTA(tBu)3 NHS ester in 1 ml of DMF was added. Constant stirring was maintained at RT for 18 h. The compound was purified by preparative HPLC (Symmetry C18 column, 19 ×300 mm, A = H2O + 0.1% formic acid and B = CH3CN + 0.1% formic acid; linear gradient 100% A to 75% B in 40 min, starting 10 min after injection, flow rate = 15 ml/min, retention time = 30.1 min). After lyophilization, 46.7 mg (0.054 mmol; yield = 90%) of DOTA(tBu)3-GPI was obtained. The purity of the compound was assessed by analytical LC-MS (Symmetry C18 column, 4.6 × 150 mm, A = TEAA 10 mM, pH 7 and B = MeOH, linear gradient 100% A to 100% B in 15 min, starting 3 min after injection, flow rate = 1 ml/min, retention time = 16.8 min). ES-TOF(−): calculated C38H67N5O15P: m/z 864.4377 [M - H]− found 864.4366.

Synthesis of DOTA-GPI

40 mg (0.046 mmol) of DOTA(tBu)3-GPI was dissolved in 2 ml of pure trifluoroacetic acid. The solution was stirred at RT for 2 h then lyophilized. The desired compound was obtained without further purification as a white powder (yield = 95%). The purity of the compound was assessed by analytical LC-MS (Symmetry C18 column, 4.6 × 150 mm, A = TEAA 10 mM, pH 7 and B = MeOH, linear gradient 100% A to 40% B in 30 min, starting 5 min after injection, flow rate = 1 ml/min, retention time = 10.7 min). ES-TOF(−): calculated C26H43N5O15P: m/z 696.2499 [M - H]− found 696.2496.

Synthesis of [In-DOTA]-GPI

The chelation of In3+ was performed by adding 225 µl of 10 mM InCl3 (2.25 µmol) in water to a solution of 2.15 µmol of DOTA-GPI in 775 µL of 0.5 M HAc/Ac− buffer, pH 5.5. The reaction mixture was incubated at RT for 1 h. The compound was purified by preparative HPLC (Symmetry C18 column, 19 × 300 mm, A = TEAA 10 mM, pH 7 and B = MeOH, linear gradient 100% A to 40% B in 35 min, starting 5 min after injection, flow rate = 15 ml/min, retention time = 9.5 min)). After lyophilization, the purity of the compound was assessed by LC-MS (Symmetry C18 column, 4.6 × 150 mm, A = TEAA 10 mM, pH 7 and B = MeOH, linear gradient 100% A to 40% B in 15 min, starting 3 min after injection, flow rate = 1 ml/min, retention time = 9.3 min).

Synthesis of [Y-DOTA]-GPI

The chelation of Y3+ was performed by adding 180 µl of 10 mM Y(NO3)3 (1.80 µmol) in water to a solution of 1.72 µmol DOTA-GPI in 820 µL of 0.5 M HAc/Ac− buffer, pH 5.5. Incubation, preparative HPLC and analytical LC/MS were performed as described for [In-DOTA]-GPI, except retention time of [Y-DOTA]-GPI was 9.2 min for preparative HPLC and 8.9 min for analytical LC-MS.

Synthesis of [Gd-DOTA]-GPI

The chelation of Gd3+ was performed by adding 250 µl of 100 mM GdCl3 (25 µmol) in water to a solution of 21.5 µmol (15 mg) of DOTA-GPI in 785 µL of 0.5 M HAc/Ac- buffer, pH 5.5. Incubation, preparative HPLC and analytical LC/MS were performed as described for [In-DOTA]-GPI, except retention time of [Gd-DOTA]-GPI was 9.3 min for preparative HPLC and 9.1 min for analytical LC-MS.

GPI Conjugation and Chelate Loading of Re and Tc

All radioactive gamma chemistry was performed in a custom hot cell (Capintec, Ramsey, NJ) as described in the text. Custom lead enclosures were constructed by Atlantic Nuclear (Canton, MA). A six-column manifold was constructed by mounting two Rheodyne model 7060 6-position valves onto the model 7725i manual injector kit and extending the backplate with a piece of plexiglass to which was mounted column holding clips (model 18515A37, McMaster-Carr, Chicago, IL).

MAS3-NHS was synthesized as described previously [12]. Conjugation was performed by mixing 1 mM GPI and 80 mM triethylamine together in dry DMSO and adding 1 mM MAS3-NHS. After constant stirring at RT overnight, a 10 µL sample of the reaction was separated on a Symmetry C18 (4.6 × 150 mm) column, with a gradient of 100% A (10 mM TEAA, pH 7.0) to 20% B (MeOH) over 30 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Eluate was analyzed simultaneously by ELSD and LC/MS, and the desired fraction identified. After dilution of the reaction with 10 mM TEAA to a total volume of 5 ml, the desired GPI-MAS3 conjugate was purified on the nonradioactive preparative HPLC sub-system using a Symmetry C18 19 × 150 mm preparative column and the above gradient. Fractions were combined and solvents were removed by freeze-drying yielding GPI-MAS3 as a white powder with a 55% yield.

For chelation with 185Re, a 0.1 ml solution of GPI-MAS3 in citrate buffer, pH 5.0 was mixed with 8.3 µL of 5 mM NaReO4, followed by the addition of 25 µL of 200 mM SnCl2. The reaction was incubated at 90°C for 1 h, and the chelated product analyzed and purified as described for GPI-MAS3.

For chelation with 99mTc, a 0.1 ml solution of GPI-MAS3 in MES buffer, pH 5.6 was mixed with 0.12 ml of 17 mM Na+/K+ tartrate and 5–10 mCi of 99mTcO4 −. 10 µL of 2 mg/ml (8 mM final) SnCl2 was added, and the vial heated to 100°C for 10 min. The chelated product was analyzed on the radioactive HPLC sub-system using the conditions described for GPI-MAS3 and purified to homogeneity.

High-Throughput, Radioactive Live Cell Binding and Affinity Assay

Human prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and PC-3 were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech Cellgro, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, Woodland, CA) and 5% penicillin/streptomycin (Cambrex Bioscience, Walkersville, MD) under humidified 5% CO2. Cells were split onto 96-well filter plates (model MSHAS4510, Millipore, Bedford, MA) and grown to 50% confluence (approximately 35,000 cells) over 48 h.

To confirm live cell binding and assign absolute affinity to each compound, a competitive displacement assay was employed using radiolabeled MAS3-GPI and the cold test compound. To avoid internalization of the radioligand due to constitutive endocytosis [1], live cell binding was performed at 4°C. Cells were washed 2 times with ice-cold tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4 and incubated for 20 min at 4°C with 100 µCi [99mTc-MAS3]-GPI in the presence or absence of the agent being tested. Cells were then washed 3 times with TBS and the well contents transferred directly to 12 × 75 mm plastic tubes placed in gamma counter racks. Transfer was accomplished using a modified (Microvideo Instruments, Avon, MA) 96-well puncher (Millipore MAMP09608) and disposable punch tips (Millipore MADP19650). Well contents were counted on a model 1470 Wallac Wizard (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA) ten-detector gamma counter.

Near-Infrared Fluorescence and Gamma Radioscintigraphic Imaging

To assess viability and verify confluence, living cells were loaded with the NIR fluorophore IR-786 by adding it to cell culture medium at 1 µM for 30 min at 37°C [13]. Simultaneous color video and NIR fluorescence imaging was performed as described in detail previously [14,15]. Gamma radioscintigraphy was performed with an Isocam Technologies (Castana, IA) Research Digital Camera equipped with a 1/2" NaI crystal, 86 photomultiplier tubes, and high-resolution low energy lead collimator.

Acknowledgment

We thank Pavel Majer, Takashi Tsukamoto, and Barbara Slusher from MGI Pharma for supply of the GPI compound, Joanne Fortunato and Thomas E. Wheat from Waters Corporation for many helpful discussions, Michael Paszak and Victor Laronga (Microvideo Instruments) for custom machining, John Viscovic (Capintec) for construction of the custom hot cell, John Anderson, Sr. and John Anderson, Jr. (Atlantic Nuclear) for custom lead enclosures, Barbara L. Clough for editing, and Grisel Rivera for administrative assistance. This work was funded by NIH grant R01-CA-115296 (JVF), and grants from the Lewis Family Fund (JVF) and the Ellison Foundation (JVF).

Abbreviations

- CH3CN

acetonitrile

- ELSD

evaporative light scattering detector

- ES-TOF

electrospray time-of-flight

- GPI

Guilford compound 11245-36

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MeOH

absolute methanol

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NIR

near-infrared

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- TEAA

triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.0

References

- 1.Humblet V, Lapidus R, Williams LR, Tsukamoto T, Rojas C, Majer P, Hin B, Ohnishi S, De Grand AM, Zaheer A, Renze JT, Nakayama A, Slusher BS, Frangioni JV. High-affinity near-infrared fluorescent small-molecule contrast agents for in vivo imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:448–462. doi: 10.2310/7290.2005.05163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grauer LS, Lawler KD, Marignac JL, Kumar A, Goel AS, Wolfert RL. Identification, purification, and subcellular localization of prostate-specific membrane antigen PSM' protein in the LNCaP prostatic carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4787–4789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farokhzad OC, Jon S, Khademhosseini A, Tran TN, Lavan DA, Langer R. Nanoparticleaptamer bioconjugates: a new approach for targeting prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7668–7672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry MD, Wen S, Silva MD, Chandra S, Milton M, Worland PJ. A prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted monoclonal antibody-chemotherapeutic conjugate designed for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7995–8001. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Huang H, Donate F, Dickinson C, Santucci R, El-Sheikh A, Vessella R, Edgington TS. Prostate-specific membrane antigen directed selective thrombotic infarction of tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5470–5475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDevitt MR, Barendswaard E, Ma D, Lai L, Curcio MJ, Sgouros G, Ballangrud AM, Yang WH, Finn RD, Pellegrini V, Geerlings MW, Jr, Lee M, Brechbiel MW, Bander NH, Cordon-Cardo C, Scheinberg DA. An alpha-particle emitting antibody ([213Bi]J591) for radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6095–6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, Simon J, Borchardt P, Frank RK, Wu K, Pellegrini V, Curcio MJ, Miederer M, Bander NH, Scheinberg DA. Tumor therapy with targeted atomic nanogenerators. Science. 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith-Jones PM, Vallabahajosula S, Goldsmith SJ, Navarro V, Hunter CJ, Bastidas D, Bander NH. In vitro characterization of radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies specific for the extracellular domain of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5237–5243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glish GL, Vachet RW. The basics of mass spectrometry in the twenty-first century. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:140–150. doi: 10.1038/nrd1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valiaeva N, Bartley D, Konno T, Coward JK. Phosphinic acid pseudopeptides analogous to glutamyl-gamma-glutamate: synthesis and coupling to pteroyl azides leads to potent inhibitors of folylpoly-gamma-glutamate synthetase. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5146–5154. doi: 10.1021/jo010283t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang F, Qu T, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. NHS-MAS3: a bifunctional chelator alternative to NHS-MAG3. Appl Radiat Isot. 1999;50:723–732. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(98)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama A, Bianco AC, Zhang CY, Lowell BB, Frangioni JV. Quantitation of brown adipose tissue perfusion in transgenic mice using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:37–49. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Grand AM, Frangioni JV. An operational near-infrared fluorescence imaging system prototype for large animal surgery. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:553–562. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakayama A, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Frangioni JV. Functional near-infrared fluorescence imaging for cardiac surgery and targeted gene therapy. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:365–377. doi: 10.1162/15353500200221333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]