Abstract

Genomic instability plays an important role in most human cancers. To characterize genomic instability in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), we examined loss of heterozygosity (LOH), copy number (CN) loss, CN gain, and gene expression using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K (n=30 cases) and Human U133A (n=17 cases) arrays in ESCC cases from a high-risk region of China. We found that genomic instability measures varied widely among cases and separated them into two groups: a high-frequency instability group (two-thirds of all cases with one or more instability category ≥ 10%) and a low-frequency instability group (one-third of cases with instability < 10%). Genomic instability also varied widely across chromosomal arms, with the highest frequency of LOH on 9p (33% of informative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)), CN loss on 3p (33%), and CN gain on 3q (48%). Twenty-two LOH regions were identified: four on 9p, seven on 9q, four on 13q, two on 17p, and five on 17q. Three CN loss regions – 3p12.3, 4p15.1, and 9p21.3 – were detected. Twelve CN gain regions were found, including six on 3q, one on 7q, four on 8q, and one on 11q. One of the most gene-rich of these CN gain regions was 11q13.1-13.4, where 26 genes also had RNA expression data available. CN gain was significantly correlated with increased RNA expression in over 80% of these genes. Our findings demonstrate the potential utility of combining CN analysis and gene expression data to identify genes involved in esophageal carcinogenesis.

Keywords: esophageal cancer, LOH, copy number alteration, 500K SNP array

Introduction

Genomic instability plays an important role in most human cancers (1-3). Several questions arise regarding genomic instability in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (ESCCs): (i) How prevalent is genomic instability in these tumors? (ii) Is there a relation between different types of genome-wide instability in ESCC, such as LOH and CN loss/gain? (iii) What is the association between genomic instability and risk factors and clinical phenotypes? The ability to answer some of these questions may lead to a better understanding of tumorigenesis and the development of new strategies for prevention, early detection, and therapy.

A combined analysis of changes in both DNA and RNA from tumors is a useful approach to identifying DNA alterations that are important for tumor development, and genome-wide genomic instability and gene expression have been simultaneously evaluated for several different cancer types (4, 5). Such integrated analysis for ESCC has been examined only once previously, and then only in a study of cell lines (6). Identification of DNA alterations in early stage tumors can be used for cancer diagnosis as well as etiology and prevention. High-throughput identification of genetic alterations that affect gene expression remains a challenging task. Recently several reports focused on the relation between DNA variants and gene expression in the human genome and tumors using several methods, most commonly comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) (7-16). So far, analyses based on the identification of genetic loci have not been resolved at the level of individual genes and polymorphic alleles that affect gene expression (17).

ESCC is a common malignancy worldwide and one of the most common cancers in the Chinese population; Shanxi Province in north central China has some of the highest esophageal cancer rates in the world (18, 19). Previously, we identified several regions of LOH and CN alteration in ESCC using microsatellite markers and low-density SNP arrays (20-24). Here we analyzed DNA from 30 micro-dissected ESCC tumors and compared them to germ-line DNA from the same case using the Affymetrix 500K SNP array. First, we examined relations among three types of genome-wide instability – LOH, CN loss, and CN gain – and then examined associations of these genomic instability measures to ESCC risk factors, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. Second, we identified regions with particularly high LOH and DNA CN change that may contain specific tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes related to ESCC tumorigenesis or disease progression. Third, we compared findings from the current study with our two previously published studies of genome-wide ESCC LOH in the same population. Finally, we compared individual gene CN alteration and mRNA expression.

Materials and Methods

Case selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Shanxi Cancer Hospital and the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). Cases diagnosed with ESCC between 1998 and 2001 in the Shanxi Cancer Hospital in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, PR China, and considered candidates for curative surgical resection were identified and recruited to participate in this study. None of the cases had prior therapy and Shanxi was the ancestral home for all. After obtaining informed consent, cases were interviewed to obtain information on demographics, cancer risk factors (smoking, alcohol drinking, and detailed family history of cancer), and clinical information. Cases were followed for survival status to the end of 2003. The cases evaluated here were part of a larger case-control study of upper gastrointestinal cancers conducted in Shanxi Province (25).

Biological specimen collection and processing

Venous blood (10 ml) was taken from each case prior to surgery and germ-line DNA from whole blood was extracted and purified using the standard phenol/chloroform method.

Tumor and adjacent normal tissues were dissected at the time of surgery and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. One 5-micron section was H&E stained and reviewed by a pathologist from NCI to guide the micro-dissection. Five to ten consecutive 8-micron sections were cut from fresh frozen tumor tissues. Tumor cells were manually micro-dissected under light microscopy. DNA was extracted from micro-dissected tumor as previously described (26) using the protocol from Puregene DNA Purification Tissue Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). RNA from tumor and matched normal tissue was extracted using the protocol from PureLink Micro-to-midi total RNA purification system (Catalog number 12183-018, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA quality and quantity were determined using the RNA 6000 Labchip/Aligent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Germantown, MD).

Target preparation for GeneChip Human Mapping 500K array set

The Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K array set contains ∼262,000 (Nsp I array) and ∼238,000 (Sty I array) SNPs (mean probe spacing = 5.8Kb, mean heterozygosity = 27%) according to the manufacture protocol.

Experiments were conducted according to the protocol (GeneChip Mapping Assay manual) supplied by Affymetrix, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, DNA samples were diluted to approximately 50ng/uL in reduced EDTA TE Buffer (0.1mM EDTA) and assayed according to the GeneChip Mapping Assay manual. A total of 250ng of DNA was digested with Nsp I or Sty I for 120 minutes at 37°C, and the reaction was inactivated at 65°C for 20 minutes. The digested DNA was then ligated to Nsp I or Sty I adaptors for 180 minutes at 16°C, followed by 20 minutes at 70°C before subsequent PCR amplification. All aforementioned steps were carried out in the pre-PCR clean room. The PCR protocol consisted of: 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 68°C for 15 seconds, with a final extension at 68°C for 7 minutes. PCR was performed with the DNA Engine Tetrad PTC-225 (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). After PCR, a mixture of 3uL of PCR product and 3uL of the 2X Gel Loading Dye was electrophoresed on a 2% Tris-borate EDTA gel at 120V for 30 minutes to assess successful amplification. If the expected product sizes (200 to 2000bp) were observed, purification and elution of the PCR products were performed using Qiagen MiniElute 96 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), followed by DNA quantification using spectrophotomeric analysis. Samples were diluted to a final concentration of 90ug in 45uL volume for fragmentation at 37°C for 35 minutes, followed by 95°C for 15 minutes. Fragmentation was verified by performing electrophoresis of 4ul of fragmented DNA from each sample in a 4% Tris-borate EDTA gel at 120V for 30 minutes. Successful fragmentation was confirmed by the presence of a smear between 50 to 200bp. The samples were end-labeled with biotin and hybridized onto the array. The chip was incubated at 49°C for 18 hours in the Affymetrix Genechip system hybridization oven, then washed and stained in the Genechip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) following the manufacturer's instructions. The chip was scanned with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 using GeneChipOperating System 1.4, and the data files were automatically generated. Genotype calls were generated by GTYPE v 4.0 software (Affymetrix). Germ-line and tumor DNA from each case were run together in parallel in the same experiment (ie, same batch, same day). The GEO accession number for these array data is GSE15526.

Probe preparation and hybridization for Human Genome U133A 2.0 array

The Human U133A 2.0 array is a single array representing 14,500 well-characterized human genes (Affymetrix). The array experiment was performed using 1-5μg total RNA; reverse transcription, labeling, and hybridization followed the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Genechip 500K array data analysis

Probe intensity data from the Affymetrix 500K SNP array was used to identify autosomal alterations in the present study.

LOH was defined in a traditional manner as a change in genotyping call from heterozygous (AB) in the germ-line DNA to homozygous (AA or BB) in the matched micro-dissected tumor DNA (all genotype calls generated by using GTYPE, Affymetrix).

CN loss or gain was based on a comparison of tumor with germ-line DNA. Microarray data were first normalized using the gtype-probeset-genotype package included in Affymetrix Power Tools version 1.85. Each tumor sample was individually normalized via the BRLMM algorithm along with 99 blood samples. These blood samples were obtained from the 30 ESCC cases evaluated in the present study plus 69 healthy controls (age-, sex-, and region-matched to cases) who were all part of a larger case-control study of upper gastrointestinal cancers conducted in Shanxi Province. Paired CN analysis was then performed on each tumor sample using the Affymetrix Copy Number Analysis Tool (CNAT). DNA obtained from the case's blood served as the normal control; a window of 100kb was chosen to optimize the identification of extended regions of CN alteration. The output of the CNAT program is CN state rather than an absolute CN prediction: normal CN corresponds to a state of 2; zero and 1 correspond to CN loss; and states 3 and 4 correspond to CN gain. Therefore we treated CN loss or gain as a qualitative trait.

Case genomic instability

Each case was categorized as high or low status for each of the three genomic instability measures (LOH, CN loss, CN gain) based on his/her frequency across the entire genome using a cutoff of 10% (≥ 10% = high, < 10% = low), which was approximately a median split for each measure (Table 1A). An overall genomic instability score was calculated for each case as follows: a case was coded “0” for no high (ie, ≥ 10%) genomic alterations (LOH, CN loss, or CN gain), “1” for one high measure, “2” for two high measures, and “3” for all three measures high. Cases with “0” genomic instability score were called the low-frequency genomic instability group; cases with scores “1”, “2”, or “3” were the high-frequency genomic instability group.

Table 1A. ESCC case clinical characteristics, risk factors, and genome-wide genomic instability measures*.

| Clinical characteristics and risk factors | Genome-wide genomic instability measure | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | ID | Age/Sex | Tumor stage | Tumor grade | Metastasis (Y/N) | Survival status | Survival days | Smoking (Y/N) | FH of cancer | LOH frequency | CN loss frequency | CN gain frequency |

| (No. informative SNPs) | (488745 SNPs) | (488745 SNPs) | ||||||||||

| 1 | E12 | 52/F | 3 | 3 | N | Deceased | 33 | N | N | 0.00 (232516) | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| 2 | E11 | 39/M | 3 | 2 | N | Alive | 2102 | Y | N | 0.00 (226150) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 3 | E19 | 65/F | 3 | 3 | Y | Deceased | 436 | N | N | 0.00 (230529) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | E5 | 53/F | 2 | 2 | N | Deceased | 498 | N | Y | 0.00 (231543) | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| 5 | E15 | 59/F | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 213 | N | N | 0.01 (227331) | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| 6 | E2 | 63/F | 3 | 2 | Y | NA | N | N | 0.01(221351) | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| 7 | E16 | 40/M | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 790 | Y | N | 0.02 (212111) | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| 8 | E28 | 52/F | 3 | 3 | Y | Deceased | 675 | N | N | 0.02 (217088) | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| 9 | E20 | 60/F | 3 | 2 | N | NA | N | Y | 0.02 (219180) | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| 10 | E9 | 57/M | 2 | 2 | N | Alive | 1860 | Y | Y | 0.03 (209005) | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| 11 | E18 | 54/F | 3 | NA | N | Deceased | 579 | N | N | 0.03 (213437) | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| 12 | E3 | 64/M | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 997 | Y | N | 0.04 (209160) | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| 13 | E7 | 50/F | 3 | 2 | N | Alive | 1878 | Y | N | 0.04 (212128) | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| 14 | E8 | 47/M | 3 | NA | Y | Deceased | 650 | Y | N | 0.04 (213257) | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 15 | E13 | 49/M | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 348 | Y | N | 0.09 (200938) | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| 16 | E22 | 64/F | 3 | 3 | Y | Deceased | 331 | N | N | 0.12 (216088) | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| 17 | E27 | 66/F | 3 | 2 | Y | NA | Y | N | 0.13 (199421) | 0.18 | 0.14 | |

| 18 | E21 | 57/F | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 339 | N | Y | 0.13 (203359) | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| 19 | E6 | 47/F | 2 | 2 | N | Alive | 1630 | N | Y | 0.14 (202987) | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 20 | E17 | 56/F | 2 | NA | Y | Deceased | 173 | N | N | 0.14 (203492) | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| 21 | E23 | 45/F | 3 | 2 | N | Alive | 1582 | N | N | 0.14 (214279) | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| 22 | E10 | 67/M | 3 | 2 | N | Alive | 1771 | Y | N | 0.15 (206914) | 0.09 | 0.20 |

| 23 | E14 | 56/M | 2 | 2 | N | Alive | 1818 | N | N | 0.16 (195598) | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| 24 | E24 | 58/F | 3 | 3 | N | Deceased | 666 | N | Y | 0.16 (206115) | 0.21 | 0.11 |

| 25 | E25 | 42/F | 3 | 2 | N | Alive | 1530 | N | Y | 0.17 (199721) | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| 26 | E29 | 56/M | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 313 | Y | Y | 0.19 (189675) | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| 27 | E1 | 62/F | 3 | 2 | Y | Deceased | 656 | N | N | 0.31(195363) | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| 28 | E26 | 49/F | 3 | 2 | N | Deceased | 182 | N | N | 0.33 (215189) | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| 29 | E30 | 40/M | 3 | 2 | N | Deceased | 608 | Y | Y | 0.38 (202783) | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| 30 | E4 | 58/M | 2 | 2 | Y | Alive | 1938 | Y | N | 0.39 (193783) | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| Table 1B. Summary of ESCC case status by type and number of genomic instability measures | ||||||||||||

| Type of genomic instability measure by frequency group | ||||||||||||

| Group | LOH (no. cases) | CN loss (no. cases) | CN gain (no. cases) | |||||||||

| High frequency (≥ 10% SNPs altered) | 15 | 11 | 18 | |||||||||

| Low frequency (< 10% SNPs altered) | 15 | 19 | 12 | |||||||||

| Altered genomic instability measures by number of cases | ||||||||||||

| No. high frequency genomic instability measures present | No. cases | |||||||||||

| 3 | 9 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 7 | |||||||||||

| 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| 0 | 11 | |||||||||||

| Total | 30 | |||||||||||

ESCC cases sorted in ascending order of LOH frequency

Chromosomal arm high genomic instability

A chromosomal arm was considered to show high genomic instability (ie, high LOH or high CN loss or high CN gain) when the average instability frequency among all cases combined for all SNPs (informative SNPs only for LOH, all SNPs for CN loss/gain) across the entire chromosomal arm was ≥ 10% for the specific genomic instability measure of interest. To maximize the likelihood that we would identify only true, “non-random” areas of change, for a chromosomal arm to be called high genomic instability, we also required that the instability measure be present in ≥ 50% of SNPs in at least 20% (n=6) of cases.

Subchromosomal region LOH

To identify focal regions of LOH, we also evaluated SNPs in cytobands. For consideration, a region had to have a minimum size of 15 informative SNPs. We declared an LOH region only when all informative markers showed LOH in at least 10% (n=3) of cases, with LOH in a minimum one-third of informative SNPs in at least 15% (n=4) of cases.

Subchromosomal region CN loss/gain

We also identified focal regions of CN loss/gain in cytobands. We declared a CN loss (gain) region when, within a sliding windows of 30 consecutive SNPs (regardless of genotype call), all 30 markers showed CN loss (gain) in at least 30% (n=9) of cases, and at least one-sixth of the markers showed CN loss (gain) in at least 50% (n=15) of cases.

Human Genome U133A 2.0 array data analysis

The Affymetrix GeneChip Human U133A 2.0 array is a single array with 22,000 probe sets representing 14,500 well-characterized human genes. Robust Multiarray Average (RMA) algorithm (27, 28) implemented in Bioconductor in R was used for background correction and normalization across all samples. We applied paired t-tests to each of the 22,000 probe sets to identify genes differentially expressed between tumor and matched normal samples. To account for multiple comparisons, we selected genes that showed significant differences with P-values less than 0.05 after Bonferroni adjustment.

Association between genomic instability and risk factor/clinical data and survival

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS) (SAS Corp, NC) for assessment of the relations between genomic instability and risk factors (smoking, family history), clinical characteristics (stage, grade, metastasis), and survival. LOH and CN alterations were modeled in several different ways. For summary genomic instability measures over the entire genome (22 autosomes), outcomes were evaluated as high versus low (defined as median split) for LOH, CN loss, and CN gain, as well as a combined average score, all in relation to individual risk and clinical factors. LOH, CN loss, CN gain, and the combined average score were also examined as continuous variables in relation to risk/clinical factors using general linear models. Additionally, we analyzed relations of LOH, CN loss, and CN gain to risk/clinical factors separately for each chromosomal arm. For the chromosomal arm-specific analyses, we divided LOH and CN alternations into high or ‘non-random’ frequency (≥ 50% of SNPs affected) versus low or ‘random’ frequency (<50% of SNPs affected). Overall survival was examined by LOH and CN alteration status (high versus low frequency categorized as ≥ 50% versus <50% of SNPs affected) per chromosomal arm with Kaplan-Meier curves; differences were tested using the log-rank test. Pearson correlation analyses were used for comparisons between CN alterations and gene expression levels in tumors. All P-values were two-sided and considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Risk factors and clinical characteristics for cases are shown in Table 1A. The average age of cases was 54 years (range 39-67), females predominated (19 of 30), approximately one-third smoked (nearly all males), and about one-third had a positive family history of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) cancer. Tumors were most commonly Stage 3 (24 of 30) and Grade 2 (24 of 30), one-half the cases had metastatic disease at the time of surgery, and the median survival from the time of surgery was 666 days.

The overall average genotype call rate was 96% (89-99%) based on a total of 126 SNP array chips, including three cases whose blood DNAs were repeated on both the Nsp I and Sty I SNP arrays for quality control purposes. The average call rate for the 250K Nsp I array was 96% (90-98%) and for the 250K Sty I array was 96% (89-99%). The genotype call rates on micro-dissected tumor DNA (95% for Sty I and 96% for Nsp I) and germ-line DNA (96% for Sty I and 99% for Nsp I) were similar for both chips. The average present call rate on the Human Genome U133A array was 53% (range 51- 61%) for the 34 chips from the 17 sample pairs with sufficient tissue for RNA isolation and testing.

Case genomic instability

Genome-wide LOH, CN loss, and CN gain in the 30 ESCC cases studied here are shown in Table 1A. Using a frequency of ≥ 10% as a cutoff for high-frequency instability for each of these three measures, one-half of the cases showed high LOH, 11 cases had high CN loss, and 19 cases had high CN gain (Tables 1A and 1B). Based on our criteria for categorizing cases into high or low genomic instability groups (see Methods), 11 cases had no high genomic instability measure, three cases had one high measure, seven cases had two high measures, and nine cases had all three high measures. Altogether, 11 cases had low-frequency and 19 cases high-frequency genomic instability

LOH and CN loss/gain were analyzed in relation to the case risk factors and clinical characteristics. None of the risk factors or clinical characteristics we examined showed a significant association with any of the three genomic instability measures, with one exception: CN gain on chromosome 3q was positively associated with metastasis (nominal P = 0.025).

Overall and chromosomal arm genome-wide LOH

The overall LOH frequency for all 30 ESCC cases across all chromosomal arms combined was 10.5% (median, range < 1% to 39%) (Table 1A, cases ordered by increasing LOH frequency), while the LOH frequency for the 39 individual (autosomal) chromosomal arms (Chr 1-22) ranged from < 1% to 33% (Table 1C). Nine chromosomal arms showed high LOH frequency, including 3p, 4p/q, 9p/q, 13q, 17p/q, and 21q, based on the criteria described (Table 1C). LOH frequency overall was highest on chromosomal arm 9p (33%), where 40% of cases had LOH in at least 50% of informative SNPs (Supplementary Table 1a, cases ordered by ID).

Overall and chromosomal arm genome-wide CN loss/gain

Overall genome-wide CN loss and gain in all 30 ESCC cases are shown in Table 1A. CN loss (median 5.5%, range < 1% to 24%) was less frequent than CN gain (median 11.5%, range < 1% to 20%). Six chromosomal arms had high CN loss, including 3p, 4p/q, 8p, 9p, and 11q (Table 1C). Supplementary Table 1b shows the frequency of CN loss on these six chromosomal arms for each case; the highest CN loss occurred on 3p where 33% of cases had CN loss in at least 50% of SNPs.

Six chromosomal arms were identified with high CN gain: 3q, 7p, 8q, 14q, 20p/q (Table 1C). The number of SNPs that showed CN gain varied widely. Many cases exhibited CN gain so extensive as to essentially encompass the entire chromosomal arm. CN gain on at least 50% of SNPs was seen in 43% of cases for 3q and 40% of cases for 8q, while almost half the cases showed no CN gain at all on the remaining four chromosomal arms (ie, 7p, 14q, 20p/q) with high CN gain overall (Supplementary Table 1c).

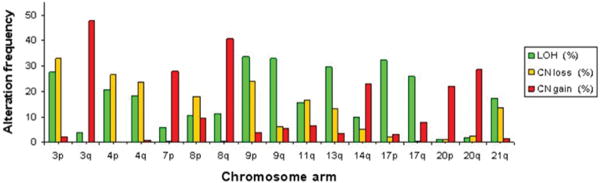

Chromosomal arm comparisons between LOH and CN loss/gain

We noted both high LOH and high CN loss on four chromosomal arms (ie, 3p, 4p/q, 9p), suggesting that LOH there was caused by chromosome loss. However, some chromosomal arms exhibited high LOH without high CN loss (ie, 9q, 13q, 17p/q, 21q), indicative of mitotic recombination or a non-disjunction event, and are target regions of interest for CN neutral LOH exploration. In contrast, chromosomal arms with high CN gain were distinct, and did not overlap with chromosomal arms that exhibited either high LOH or high CN loss (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

High instability chromosome arms in ESCC. The histograms show LOH (green), CN loss (orange), and CN gain (red). Criteria for defining genomic instability are described in Materials and Methods.

Subchromosomal region genomic instability

A total of 22 LOH regions were identified based on our criteria (see Methods), including 11 on chromosome 9, 7 on chromosome 17, and four on chromosome 13. These regions represent 395 SNPs from 21 genes (Table 2A). Three CN loss regions were found – 3p12.3, 4p15.1, and 9p21.3 – which contain 765 SNPs from seven genes (ie, CTNT3, LOC33897, LOC28529, LOC645716, MTAP, CDKN2A, and CDKN2B; Table 2B). Twelve CN gain regions were recognized: six on chromosome 3q, one on 7q, four on 8q and one on 11q; these 12 regions represented 13,343 SNPs from 482 genes (Table 2C). Among the 37 regions of genomic instability found, a single cytoband, 9p21.3, which contains CDKN2A and CDKN2B, showed both LOH and CN loss (Tables 2A and 2B).

Table 2A. Summary of LOH regions by SNPs and cases.

| Region no. | hg18 nucleotide boundaries | Cytoband | No. genes in region | No. informative SNPs | LOH region by no. of SNPs | LOH region by no. of cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. SNPs with LOH in 10 - 14% of cases | No. SNPs with LOH in ≥ 15% of cases | No. cases with LOH in ≥ 10% of SNPs | No. cases with LOH in ≥ 15% of SNPs | No. cases with LOH in ≥ 25% of SNPs | No. cases with LOH in ≥ 50% of SNPs | |||||

| 1 | chr9:14355200-14432045 | 9p22.3 | 0 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| 2 | chr9:21684039-21775304 | 9p21.3 | 0 | 36 | 24 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| 3 | chr9:29096566-29173429 | 9p21.1 | 0 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 3 |

| 4 | chr9:36965108-36997769 | 9p13.2 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| 5 | chr9:74162167-74331189 | 9q21.13 | 2 | 25 | 2 | 23 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| 6 | chr9:108856785-108943244 | 9q31.2 | 0 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 3 |

| 7 | chr9:112327376-112374428 | 9q31.3 | 1 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 3 |

| 8 | chr9:117064513-117169425 | 9q33.1 | 1 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| 9 | chr9:133710891-133789187 | 9q34.13 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 4 |

| 10 | chr9:135865842-136242947 | 9q34.2 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 3 |

| 11 | chr9:139880374-140094586 | 9q34.3 | 1 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 6 |

| 12 | chr13:37103546-37185893 | 13q13.3 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 4 |

| 13 | chr13:71667301-71724275 | 13q21.33 | 0 | 17 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 3 |

| 14 | chr13:81899127-81945971 | 13q31.1 | 0 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| 15 | chr13:109807056-109830700 | 13q34 | 1 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| 16 | chr17:2066568-2147184 | 17p13.3 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| 17 | chr17:6228993-6313993 | 17p13.2 | 2 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 3 |

| 18 | chr17:22009077-22505419 | 17q11.1 | 0 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 19 | chr17:47115727-47212755 | 17q21.33 | 1 | 19 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 2 |

| 20 | chr17:50931709-51004571 | 17q22 | 0 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 4 |

| 21 | chr17:54195586-54596720 | 17q22 | 4 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 3 |

| 22 | chr17:75750662-75826327 | 17q25.3 | 3 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| Total | 21 | 395 | 188 | 207 | ||||||

| Table 2B. Summary of CN loss regions by SNPs and cases | ||||||||||

| Region no. | hg18 nucleotide boundaries | Cytoband | No. genes in region | No. SNPs | CN loss region by no. of SNPs | CN loss region by no. of cases | ||||

| No. SNPs with CN loss in 30 - 49% of cases | No. SNPs with CN loss in ≥ 50% of cases | No. cases with CN loss in ≥ 30% of SNPs | No. cases with CN loss in ≥ 50% of SNPs | |||||||

| 1 | chr3:74200117-75879418 | 3p12.3 | 3 | 212 | 204 | 8 | 12 | 12 | ||

| 2 | chr4:30817709-32723028 | 4p15.1 | 1 | 271 | 221 | 50 | 14 | 13 | ||

| 3 | chr9:21642666-22978063 | 9p21.3 | 3 | 282 | 248 | 34 | 14 | 12 | ||

| Total | 7 | 765 | 673 | 92 | ||||||

| Table 2C. Summary of CN gain regions by SNPs and cases | ||||||||||

| Region no. | hg18 nucleotide boundaries | Cytoband | No. genes in region | No. SNPs | CN gain region by no. of SNPs | CN gain region by no. of cases | ||||

| No. SNPs with CN gain in 30 - 49% of cases | No. SNPs with CN gain in ≥ 50% of cases | No. cases with CN gain in ≥ 30% of SNPs | No. cases with CN gain in ≥ 50% of SNPs | |||||||

| 1 | chr3:127704774-131311144 | 3q21.3 | 42 | 491 | 354 | 137 | 14 | 12 | ||

| 2 | chr3:137407881-140385944 | 3q22.3 | 15 | 333 | 260 | 73 | 14 | 12 | ||

| 3 | chr3:140425733-144397917 | 3q23 | 25 | 785 | 696 | 89 | 13 | 12 | ||

| 4 | chr3:150406346-156291482 | 3q25.1-q25.2 | 39 | 955 | 263 | 692 | 19 | 13 | ||

| 5 | chr3:156303582-161199046 | 3q25.31-q25.33 | 24 | 842 | 234 | 608 | 16 | 15 | ||

| 6 | chr3:161206482-199318155 | 3q26.1-q29 | 180 | 5872 | 550 | 5322 | 22 | 20 | ||

| 7 | chr7:98095021-101704367 | 7q22.1 | 41 | 183 | 171 | 12 | 12 | 12 | ||

| 8 | chr8:80304821-84278815 | 8q21.13 | 17 | 566 | 486 | 80 | 13 | 11 | ||

| 9 | chr8:99109330-101380541 | 8q22.2 | 12 | 152 | 48 | 104 | 16 | 14 | ||

| 10 | chr8:117700533-122496459 | 8q24.11-q24.12 | 20 | 1017 | 324 | 693 | 18 | 14 | ||

| 11 | chr8:122507370-131499315 | 8q24.13-q24.21 | 30 | 1944 | 319 | 1625 | 19 | 17 | ||

| 12 | chr11:65544648-70948892 | 11q13.1-q13.4 | 37 | 203 | 132 | 71 | 17 | 11 | ||

| Total | 482 | 13343 | 3837 | 9506 | ||||||

Comparison of genome-wide LOH with the two previous studies

Genome-wide LOH results from this study are compared to two previous studies of ESCC from the same population in China in Table 3 (21, 23). Of note, the cases studied in the three studies described here were all different and non-overlapping. Our first genome-wide LOH study was performed on 11 ESCC cases and used 366 microsatellite makers with an average heterozygosity of 76%. High LOH frequencies (≥ 50%) were observed on 14 chromosomal arms (3p, 4p/q, 5q, 8p/q, 9p/q, 11p/q, 13q, 17p/q, 18p) (19). A second study performed on 26 ESCC cases used the Affymetrix 10K SNP array and found high frequency of LOH (≥ 50%) on 10 chromosomal arms (3p, 4p/q, 5q, 9p/q, 13q, 15q, 17p/q). The present study showed high LOH (≥ 10%) on nine chromosomal arms (3p, 4p/q, 9p/q, 13q, 17p/q). Table 3 shows that LOH frequency decreased as the number of markers increased, suggesting that the frequency of LOH in previous studies was overestimated by the low density marker platforms, and that the presence of LOH in ESCC tumors was not as high as previously thought. Alternative explanations for this finding include that the high density array increased the probability of markers disrupting the requirement for continguous LOH regions, or that differences in marker polymorphic information content or marker placement may have played a role. Table 3 also shows that eight chromosomal arms (3p, 4p/q, 9p/q, 13q, 17p/q) consistently showed the highest LOH frequencies across all three studies, suggesting that these regions likely contain tumor suppressor genes involved in ESCC development and disease progression.

Table 3. Comparsion of genome-wide LOH frequencies from 3 different studies of ESCC.

| Study 1 11 ESCC cases |

Study 2 26 ESCC cases |

Study 3 30 ESCC cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 366 microsatellite markers Heterozygosity 0.76 |

10K SNP array Heterozygosity 0.37 |

500K SNP array Heterozygosity 0.27 |

|

| Chr arm | % LOH | % LOH | % LOH |

| 1p | 26 (23/88) | 28 (563/1998) | 6 (16998/295640) |

| 1q | 24 (22/91) | 21 (377/1787) | 0 (10133/265992) |

| 2p | 30 (17/57) | 31 (561/1861) | 7 (16577/223205) |

| 2q | 38 (43/113) | 33 (782/2363) | 9 (28908/300767) |

| *3p | 89 (65/73) | 58 (955/1658) | 27 (51525/187767) |

| 3q | 28 (25/90) | 29 (482/1677) | 4 (7505/199734) |

| *4p | 65 (24/37) | 60 (509/846) | 21 (21824/105746) |

| *4q | 67 (62/93) | 65 (1424/2208) | 18 (39623/218248) |

| 5p | 38 (27/71) | 32 (286/906) | 0 (452/113713) |

| 5q | 79 (77/97) | 52 (1321/2560) | 10 (28687/286976) |

| 6p | 29 (8/28) | 45 (545/1226) | 5 (8794/164505) |

| 6q | 45 (38/85) | 42 (981/2351) | 1 (2484/233438) |

| 7p | 11 (6/54) | 33 (398/1201) | 6 (8608/147004) |

| 7q | 23 (19/81) | 35 (539/1551) | 8 (11086/182680) |

| 8p | 52 (27/52) | 43 (331/764) | 11 (13275/125798) |

| 8q | 52 (34/66) | 31 (550/1759) | 11 (22686/204630) |

| *9p | 81 (34/42) | 72 (867/1209) | 34 (30533/91179) |

| *9q | 86 (32/37) | 72 (714/999) | 33 (53726/163207) |

| 10p | 43 (20/47) | 37 (314/855) | 4 (4536/121213) |

| 10q | 38 (24/63) | 37 (694/1897) | 8 (21736/274831) |

| 11p | 71 (32/45) | 39 (444/1130) | 11 (15042/131731) |

| 11q | 52 (28/54) | 37 (591/1590) | 16 (30370/195457) |

| 12p | 24 (10/41) | 26 (149/576) | 7 (6213/94193) |

| 12q | 35 (30/85) | 27 (496/1874) | 4 (8832/239201) |

| *13q | 95 (73/77) | 68 (1300/1907) | 30 (57242/193786) |

| 14q | 32 (29/91) | 46 (846/1836) | 10 (20399/203814) |

| 15q | 46 (23/50) | 57 (845/1487) | 8 (15563/205215) |

| 16p | 38 (5/13) | 29 (148/520) | 2 (2113/91022) |

| 16q | 19 (9/47) | 34 (213/631) | 3 (4150/137525) |

| *17p | 69 (22/32) | 76 (246/326) | 32 (13975/43120) |

| *17q | 64 (16/25) | 67 (450/669) | 26 (29538/114393) |

| 18p | 50 (7/14) | 4.09 (142/347) | 8 (3400/40543) |

| 18q | 45 (17/38) | 48.1 (513/1067) | 12 (16285/136517) |

| 19p | 25 (5/20) | 38.9 (58/149) | 5 (2088/38710) |

| 19q | 22 (6/27) | 44.2 (184/416) | 9 (5804/62565) |

| 20p | 23 (8/35) | 31.8 (208/655) | 1 (919/88878) |

| 20q | 45 (5/11) | 33.5 (178/532) | 2 (1569/97137) |

| 21q | 42 (14/33) | 39.1 (339/866) | 17 (14315/83079) |

| 22q | 34 (12/35) | 34.9 (157/450) | 5 (5541/103776) |

| Average LOH (%) | 978/2138=0.457 | 20700/48704=0.425 | 653054/6206935=0.105 |

High LOH chromosomal arms (bold and italicized) defined as ≥ 50% LOH in studies 1 and 2, and ≥ 10% in study 3 (with ≥ 50% LOH in minimum of 20% of cases)

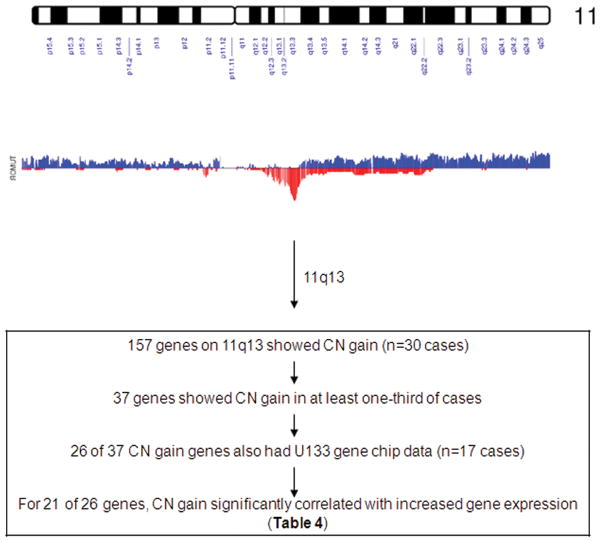

Relation between CN alterations and mRNA expression

To investigate the relationship between CN alterations and mRNA expression level, we focused our analysis on chromosome 11q13.1-q13.4, one of the CN gain regions, to evaluate the association between gene expression and CN gain. 11q13 is a highly gene rich region strongly conserved across zebrafish, mice, and humans, and it has exhibited multiple amplification peaks in several tumors (29). The high CN gain region 11q13.1-q13.4 identified in the present study contained 777 SNPs from 157 genes. We found that 37 of the 157 genes (203 SNPs) had CN gain in more than 30% of cases (range 33% - 63%). We measured RNA expression in 17 cases with sufficient frozen material available for RNA isolation from both tumor and matched normal tissues, and determined that 26 of the 37 genes represented on the U133A chip probesets were suitable for analysis. Among these 26 genes, there were strong (significant) positive correlations between CN gain and expression for 21 of 26 genes, with Pearson correlation coefficients between 0.51-0.87 (P < 0.05), including PSCA1, CCND1, CTTN, PPFIA1, and SHANK2 (Figure 2 and Table 4). The result suggests that high CN gain is associated with up-regulated gene expression. To identify specific genes in the focal CN gain regions, we will need to characterize both gene expression and other cellular activities in a larger population of cases in the future.

Figure 2.

CN gain and loss on chromosome 11. The top graph shows chromosome 11 ideogram. The middle graph displays CN loss (blue) and gain (red) frequencies across 30 cases. The bottom box describes gene selection procedure.

Table 4. Correlation between CN gain and mRNA expression for 26 genes on 11q13 in ESCC (n=17 cases).

| No. | Cytoband | Gene name/ID | No. SNPs | Frequency of cases with CN gain | Average gene expression fold-change | r | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11q13.1 | SF3B2/10992 | 2 | 0.47 | 1.64 | 0.63 | 0.0064 |

| 2 | 11q13.1 | PACS1/55690 | 26 | 0.50 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 4.32E-06 |

| 3 | 11q13.1 | BRMS1/25855 | 1 | 0.47 | 1.74 | 0.54 | 0.0266 |

| 4 | 11q13.1 | SLC29A2/3177 | 1 | 0.47 | 1.86 | 0.76 | 0.0004 |

| 5 | 11q13.1 | RAD9A/5883 | 3 | 0.47 | 2.04 | 0.67 | 0.0030 |

| 6 | 11q13.1 | RPS6KB2/6199 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.76 | -0.27 | 0.2871 |

| 7 | 11q13.2 | AIP/9049 | 2 | 0.53 | 1.85 | 0.68 | 0.0026 |

| 8 | 11q13.2 | GSTP1/2950 | 1 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.0043 |

| 9 | 11q13.2 | NDUFV1/4723 | 1 | 0.47 | 1.40 | 0.77 | 0.0003 |

| 10 | 11q13.2 | ALDH3B2/222 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.14 | 0.5950 |

| 11 | 11q13.2 | SUV420H1/51111 | 7 | 0.47 | 1.21 | 0.51 | 0.0352 |

| 12 | 11q13.2 | C11orf24/53838 | 1 | 0.47 | 1.83 | 0.66 | 0.0036 |

| 13 | 11q13.2 | LRP5/4041 | 12 | 0.53 | 2.60 | 0.72 | 0.0011 |

| 14 | 11q13.2 | SAPS3/55291 | 11 | 0.47 | 1.44 | 0.62 | 0.0082 |

| 15 | 11q13.2 | MTL5/9633 | 7 | 0.47 | 1.33 | 0.29 | 0.2603 |

| 16 | 11q13.2 | CPT1A/1374 | 7 | 0.47 | 2.14 | 0.66 | 0.0041 |

| 17 | 11q13.2 | IGHMBP2/3508 | 7 | 0.53 | 1.51 | 0.58 | 0.0144 |

| 18 | 11q13.2 | CCND1/595 | 3 | 0.65 | 1.43 | 0.59 | 0.0135 |

| 19 | 11q13.3 | FGF3/2248 | 1 | 0.71 | 2.40 | 0.28 | 0.2820 |

| 20 | 11q13.3 | TMEM16A/55107 | 20 | 0.71 | 40.91 | 0.62 | 0.0085 |

| 21 | 11q13.3 | PPFIA1/8500 | 12 | 0.65 | 7.04 | 0.74 | 0.0006 |

| 22 | 11q13.3 | CTTN/2017 | 3 | 0.59 | 3.50 | 0.64 | 0.0060 |

| 23 | 11q13.3 | SHANK2/22941 | 29 | 0.59 | 1.65 | 0.55 | 0.0209 |

| 24 | 11q13.4 | DHCR7/1717 | 4 | 0.35 | 3.44 | 0.59 | 0.0122 |

| 25 | 11q13.4 | NADSYN1/55191 | 10 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.72 | 0.0012 |

| 26 | 11q13.4 | KRTAP5-9/3846 | 2 | 0.35 | 1.03 | 0.14 | 0.6041 |

| Total | 175 | ||||||

Discussion

Our study characterized ESCC tumors for three types of genome-wide instability – LOH, CN loss, and CN gain – in germ-line DNA and matched micro-dissected tumor DNA using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K array, and is the first study to report the integration of high density LOH and CN alteration data in ESCC with gene expression analyses on a genome-wide scale.

We observed that chromosomal arms with high LOH and CN loss frequently overlapped (ie, 3p, 4p/q, 9p), suggesting that these areas potentially harbor tumor suppressor genes, as illustrated in a previous study that showed high LOH on 9p concurrent with frequent CDKN2A mutations and intragenic allelic losses (30). The present study had analogous findings: subchromosomal region 9p21.3 exhibited both high LOH (Table 2A) and high CN loss (Table 2B), while one-half the ESCC cases studied had CN loss on all five SNPs in CDKN2A, and nine cases showed biallelic loss for CDKN2A (data not shown). These data indicate that numerous types of alterations occur in CDKN2A – LOH, CN loss, biallelic loss, germ-line and somatic mutations, and intragenic allelic loss – and that these alterations collectively contribute to the inactivation of CDKN2A.

Using criteria stricter than traditionally applied, we identified 22 focal subchromosomal regions of LOH. These regions were found on 9p/q, 13q, and 17p/q, similar to a previous LOH study in which we utilized the Affymetrix 10K SNP array (24). Both studies employed micro-dissected tumor and matched germ-line DNA, which we believe are essential approaches to obtaining consistent LOH results. The concordance of findings between these two LOH studies using similarly rigorous methods increases our confidence in the importance of emphasizing these 30 regions in future studies to identify ESCC tumor suppressor genes.

Six chromosomal arms showed high CN loss and six arms showed high CN gain, but over all 22 autosomal chromosomes, CN gain occurred twice as often as CN loss. There was no overlap in the chromosomal arms which showed high CN gain compared to arms which showed high CN loss, nor did high CN gain arms overlap with high LOH arms. This is consistent with observations that chromosome-wide CN gain is limited to one or two copies (trisomy or tetrasomy), while high level amplification tends to be a focal event (eg, gene amplification at 11q13 encompassing CCND1). While there have been several previous reports of CN alterations in ESCC, most have used low-resolution comparative genomic hybridization methods (6, 24, 31-36). Two have used SNP-based array methods (24, 36), comparable to the present study, but these were also low-resolution arrays.

We previously reported that CDC25B over-expressed both mRNA (37, 38) and protein in ESCC tumors and dysplasias (38). CDC25B is located on 20p13, a chromosomal arm with high CN gain in the present study, where we also observed that 30% of ESCC cases showed CN gain in CDC25B (data not shown), suggesting that CN gain is responsible for CDC25B over-expression in at least a subset of persons with pre-malignant and invasive ESCC.

Among the 12 CN gain regions identified, six were on 3q, four on 8q, one on 7q22.1, and one on 11q13.1. We focused on 11q13.1, the most gene-rich of these gain regions. Several genes on chromosomal region 11q13 which were amplified in this study are known oncogenes whose amplification has been associated with poor prognosis (39). For example, PPFIA1 is a member of a family of leukocyte common antigen-related (LAR) trans-membrane tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins. Recently, Tan et al reported that PPFIA1 was over-expressed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), and suggested that this gene may act as an invasion inhibitor in HNSCC (29). PPFIA1 was highly (7-fold) over-expressed in our data, and expression was highly correlated with CN (Table 4).

In summary, our study demonstrated that genomic instability varied widely among ESCCs and included cases with both high and low frequencies; the high-frequency instability group may harbor germ-line variants or acquired somatic mutations in genes that maintain genomic stability. Genome-wide studies from this high-risk population show a consistent pattern of high LOH on selected chromosome arms which are targets in searching for loss-of-function genes involved in ESCC. Our findings also demonstrate the potential utility of combining CN and gene expression data to identify genes involved in esophageal carcinogenesis. Future studies should combine results in tumors with germ-line genotypes to find functional changes, and determine if these changes are associated with genetic susceptibility to ESCC or might serve as early detection markers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Stephen Hewitt of NCI for reviewing the slides used for micro-dissection. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, the National Cancer Institute, the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, and the Center for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations used

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- CN

copy number

- GCOS

GeneChip Operating System

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

References

- 1.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–9. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitelman Database of Chromsome Aberrations in Cancer. 2008 http://cgap nci nih gov/Chromsomes/Mitelman.

- 3.Bodmer W, Bielas JH, Beckman RA. Genetic instability is not a requirement for tumor development. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3558–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukamoto Y, Uchida T, Karnan S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number alterations and gene expression in gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2008;216:471–82. doi: 10.1002/path.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Tayrac M, Etcheverry A, Aubry M, et al. Integrative genome-wide analysis reveals a robust genomic glioblastoma signature associated with copy number driving changes in gene expression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:55–68. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimoto T, Arai M, Shimada H, Hata A, Seki N. Integrated analysis of expression and genome alteration reveals putative amplified target genes in esophageal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:465–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergamaschi A, Kim YH, Wang P, et al. Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1033–40. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gysin S, Rickert P, Kastury K, McMahon M. Analysis of genomic DNA alterations and mRNA expression patterns in a panel of human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44:37–51. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidenblad M, Lindgren D, Veltman JA, et al. Microarray analyses reveal strong influence of DNA copy number alterations on the transcriptional patterns in pancreatic cancer: implications for the interpretation of genomic amplifications. Oncogene. 2005;24:1794–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, Chang B, Sauvageot J, et al. Comprehensive assessment of DNA copy number alterations in human prostate cancers using Affymetrix 100K SNP mapping array. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1018–32. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masayesva BG, Ha P, Garrett-Mayer E, et al. Gene expression alterations over large chromosomal regions in cancers include multiple genes unrelated to malignant progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8715–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400027101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack JR, Sorlie T, Perou CM, et al. Microarray analysis reveals a major direct role of DNA copy number alteration in the transcriptional program of human breast tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12963–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162471999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spielman RS, Bastone LA, Burdick JT, Morley M, Ewens WJ, Cheung VG. Common genetic variants account for differences in gene expression among ethnic groups. Nat Genet. 2007;39:226–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stransky N, Vallot C, Reyal F, et al. Regional copy number-independent deregulation of transcription in cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1386–96. doi: 10.1038/ng1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker BA, Leone PE, Jenner MW, et al. Integration of global SNP-based mapping and expression arrays reveals key regions, mechanisms, and genes important in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:1733–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan H, Yuan W, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Allelic variation in human gene expression. Science. 2002;297:1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1072545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockman MV, Kruglyak L. Genetics of global gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:862–72. doi: 10.1038/nrg1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JY. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in China. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1982;62:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiao YL, Hou J, Yang L, et al. The trends and preventive strategies of esophageal cancer in high-risk areas of Taihang Mountains, China. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2001;23:10–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu N, Roth MJ, Emmert-Buck MR, et al. Allelic loss in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients with and without family history of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3476–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu N, Roth MJ, Polymeropolous M, et al. Identification of novel regions of allelic loss from a genomewide scan of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in a high-risk Chinese population. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:217–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200003)27:3<217::aid-gcc1>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Hu N, Goldstein AM, et al. High frequency allelic loss on chromosome 17p13.3-p11.1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from a high incidence area in northern China. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2019–26. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu N, Su H, Li WJ, et al. Allelotyping of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma on chromosome 13 defines deletions related to family history. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44:271–8. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu N, Wang C, Hu Y, et al. Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity and copy number alteration in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using the Affymetrix GeneChip Mapping 10 K array. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng D, Hu N, Hu Y, et al. Replication of a genome-wide case-control study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1610–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, et al. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–93. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan KD, Zhu Y, Tan HK, et al. Amplification and overexpression of PPFIA1, a putative 11q13 invasion suppressor gene, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:353–62. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu N, Wang C, Su H, et al. High frequency of CDKN2A alterations in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma from a high-risk Chinese population. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;39:205–16. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinomiya T, Mori T, Ariyama Y, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: the possible involvement of the DPI gene in the 13q34 amplicon. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:337–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang LD, Qin YR, Fan ZM, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization: comparison between esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma from a high-incidence area for both cancers in Henan, northern China. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:459–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirasaki S, Noguchi T, Mimori K, et al. BAC clones related to prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous carcinoma: an array comparative genomic hybridization study. Oncologist. 2007;12:406–17. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-4-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin YR, Wang LD, Fan ZM, Kwong D, Guan XY. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of genetic aberrations associated with development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Henan, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1828–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carneiro A, Isinger A, Karlsson A, et al. Prognostic impact of array-based genomic profiles in esophageal squamous cell cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Guo L, Peiffer DA, et al. Genomic profiling of 766 cancer-related genes in archived esophageal normal and carcinoma tissues. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2249–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su H, Hu N, Shih J, et al. Gene expression analysis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma reveals consistent molecular profiles related to a family history of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3872–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shou JZ, Hu N, Takikita M, et al. Overexpression of CDC25B and LAMC2 mRNA and protein in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas and premalignant lesions in subjects from a high-risk population in China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1424–35. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver AM. Cortactin in tumor invasiveness. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.