Abstract

Background

Most cancer patients die at institutions despite their wish for home death. GP-related factors may be crucial in attaining home death.

Aim

To describe cancer patients in palliative care at home and examine associations between home death and GP involvement in the palliative pathway.

Design of study

Population-based, combined register and questionnaire study.

Setting

Aarhus County, Denmark.

Method

Patient-specific questionnaires were sent to GPs of 599 cancer patients who died during a 9-month period in 2006. The 333 cases that were included comprised information on sociodemography and GP-related issues; for example knowledge of the patient, unplanned home visits, GPs providing their private phone number, and contact with relatives. Register data were collected on patients' age, sex, cancer diagnosis, place of death, and number of GP home visits. Associations with home death were analysed in a multivariable regression model with prevalence ratios (PR) as a measure of association.

Results

There was a strong association between facilitating home death and GPs making home visits (PR = 4.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2 to 14.9) and involvement of community nurses (PR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0 to 1.9). No other GP-related variables were statistically significantly associated with home death.

Conclusion

Active involvement of GPs providing home visits and the use of home nurses were independently associated with a higher likelihood of facilitating home death for cancer patients. The primary care team may facilitate home death, accommodating patients' wishes. Future research should examine the precise mechanisms of their involvement.

Keywords: Denmark, family practice, neoplasm, palliative care, primary health care, terminally ill

INTRODUCTION

Most cancer patients die at institutions, despite most patients' wishing to die at home.1,2 GPs and community nurses often play an important role in palliative care at home.3,4 It has been postulated that the low percentage distribution of home deaths may be rooted in poor delivery of primary health care.5

However, studies indicate that GP involvement is associated with facilitating home death.6–9 Furthermore, despite earlier studies identifying considerable dissatisfaction with symptom control in a primary care setting,3,10 satisfaction with GPs was still rated high3 and relatives valued the involvement of GPs.11,12 All in all, it suggests that good palliative care amounts to more than simply a certain degree of symptom control.

Most extant research focuses on specialised institution-based palliative care. Studies are needed into how to support and improve GP involvement in palliative care, and to gain knowledge of the actual extent and nature of this involvement in facilitating home death.

How this fits in

Research in palliative care often focuses mainly on specialised, institutionally-based palliative care. The types and quality of primary care services may, however, be crucial in facilitating home death. This study offers new knowledge about associations between home death and primary care services, especially in relation to GP-related factors.

The aim of the present study was to describe cancer patients in palliative home care in relation to demographic characteristics, the palliative pathway, and degree of GP involvement. Another aim was to examine the association between home death and GP involvement in palliative pathways, identifying significant factors for supporting home death.

METHOD

Setting

The Danish healthcare system is financed through tax; more than 98% of Danes are registered with a GP and receive free medical care.13 Danish GPs are gatekeepers for access to specialist treatment and are responsible for frontline care 24 hours a day. Large GP cooperatives provide out-of-hours care.

All Danish citizens are registered with unique civil registration numbers.14 Through these, questionnaire data were linked to health register information.

Denmark has no formal national agreement on task distribution in palliative care, but Aarhus County provided a special fee for GP involvement in palliative care. Community nurses employed by the municipalities are often involved in palliation and visit patients on a 24-hour basis. Specialist palliative visiting teams based at the major hospitals are available during daytime hours, and specialist advice can be obtained by telephone from GPs or community nurses.

Aarhus County comprises 43 municipalities, with approximately 640 000 inhabitants at the time of the study (12% of the Danish population). Figures from 2005 indicated that 1680 people die from cancer there each year.15

Study population and sampling

Adults in Aarhus County who died from cancer from 1 March to 30 November 2006, and who had received palliative care at home either from GPs, community nurses, or palliative specialist teams were included. Since no database on palliative patients was available, and since the Danish Register of Causes of Death was still not updated on deaths in 2006, the patients were sampled by combining official register data with questionnaire information. The questionnaires were answered by patients' GPs, who were asked if palliative care had been provided in the patient's home.

From the county hospital discharge register 29 043 individuals ≥18 years of age who were registered with at least one cancer diagnosis (ICD-10) (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers) during the period November 2006 and 10 years back were identified. In December 2006, using the Civil Registration System database, 813 patients were identified among the 29 042 who died between 1 March and 30 November 2006 (9 months). From the regional health authority's register their GPs were identified. Eight (1.0%) patients were not registered with a GP and 18 (2.2%) had moved from the county after having been diagnosed, leaving 787 deceased cancer patients. A questionnaire was sent to their GPs.

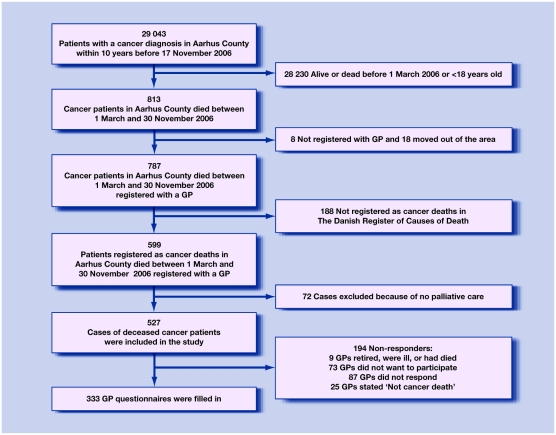

In late 2008, data from the Danish Register of Causes of Death for 2006 was available. Merging information of cause of death with the primary database, 188 patients were excluded who were not registered as cancer deaths, which reduced the study population to 599 deceased cancer patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of sampling of study population and GP questionnaires: responders and non-responders.

Data collection

GP questionnaires included themes identified through literature studies, clinical experience and group interview studies with bereaved relatives.12 It involved professionals such as GPs, community nurses, and hospital consultants (MA Neergaard, unpublished data, 2009). The 72-item questionnaire was pilot-tested among 30 GPs in another Danish county.

In partnership practices, the GPs most familiar with the patients were asked to answer the questionnaire. GPs received a small economic compensation for their efforts. Non-responders were sent reminders 4 and 7 weeks following the first questionnaire.

Retrieved were register data on patients' age (18–65, ≥66 years), sex, cancer diagnosis (lung, colorectal, breast, prostate, other), place of death, home visits provided by GPs (0, 1, 2, 3, >3, and dichotomised into no/yes) in the period 3 months prior to the patients' death. The questionnaires included information on the patients' marital status (single, married, or cohabiting), patients' children (no, yes at home, yes not at home), GPs' knowledge of the patient before the palliative period (dichotomised into poor [1, 2 on a 1–5 point scale] and good [3, 4, and 5]), whether GPs provided their private phone number for emergency advice (no/yes), whether GPs had contact with patients' relatives (no/yes), whether community nurses (no/yes) or a specialist team (no/yes) were involved, and the duration of the palliative period at home and in total. The palliative period was defined as the last period of the patient's life during which all curative treatment had ceased and care and treatment were solely palliative.

Analysis

‘Home death’ was defined as the outcome measure and associations between home death and patient, GP, and palliative pathway variables were analysed. Place of death is defined in the Danish Register of Causes of Death as ‘home’, ‘nursing home’, ‘hospital or hospice’ and ‘death in other places’. Since the patient's own GP provides care for the patient at home as well as in nursing homes, ‘home death’ was defined as death either at home or at a nursing home. GPs are rarely involved in palliative pathways at hospices, but the register data did not allow separation between hospital and hospice deaths.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations were calculated. Using robust variance estimates, the estimates were adjusted for clustering of patients in practices.16 Prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as a measure of association. Due to the high prevalence of the outcome measure (more than 20% home deaths), odds ratios would overestimate the association.17 PRs were calculated with generalised linear models with log link and within the Bernoulli family, and since the model could not converge, the Poisson regression model was used.17,18

The variables were assessed for collinearity (Pearson's correlation coefficient >0.4) and multicollinearity (variance inflation factor [VIF] <10). [Explanation: If VIF of an independent variable is x, it means that the standard error of that variable's coefficient is √x times as large as it would be if the variable were uncorrelated with other independent variables.]19 None of the included variables had to be excluded because of collinearity. The duration of the palliative period spent at home was also added as a confounder, since it could be associated with GPs' possibility to provide palliative services. Data were analysed using STATA 10 (Stata Statistical Software, Release 10, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Among the 599 questionnaires sent to GPs, 72 were excluded because GPs stated that no home care was provided during the palliative pathway. Of the remaining 527 included patient deaths, a total of 333 questionnaires from 231 general practices were filled in (response rate 63.2%) (Figure 1). Characteristics of cases included in the study are seen in Table 1. The case data are derived from GP questionnaires and registers, while data on cases from GPs who did not respond are from registers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 333 included cases and 194 cases not included because the GP did not respond.a

| Cases in study (n = 333) | Cases of non-responders (n = 194) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient's age at time of death, years mean (95% CI) | 69.4 (68.0 to 70.8) | 73.5 (71.7 to 75.3)b | |

| Patient's sex, n (%): | Male | 181 (54.4) | 113 (58.3) |

| Female | 152 (45.6) | 81 (41.7) | |

| Primary cancer diagnosis, n (%): | Bronchus/lung | 65 (19.5) | 37 (19.1) |

| Colon/rectum | 50 (15.1) | 32 (16.5) | |

| Breast | 34 (10.2) | 22 (11.3) | |

| Prostate | 39 (11.7) | 31 (16.0) | |

| Other | 145 (43.5) | 72 (37.1) | |

| Patient's marital status, n (%): | Single | 125 (39.8) | – |

| Married | 189 (60.2) | ||

| Having children, n (%): | No | 32 (11.0) | – |

| Yes, living at home | 34 (11.7) | ||

| Yes, adults | 226 (77.3) | ||

| Place of death, n (%): | Home | 120 (36.0) | 70 (36.1) |

| Nursing home | 69 (20.7) | 51 (26.3) | |

| Hospital/hospice | 140 (42.0) | 70 (36.1) | |

| Other (for example other institution) | 4 (1.2) | 3 (1.5) | |

| GP involvement in palliation, n (%): | No | 37 (11.3) | – |

| Yes | 290 (88.7) | ||

| GP's knowledge prior to palliative period, n (%): | Poor | 44 (13.3) | – |

| Well | 279 (86.7) | ||

| Number of home visits by GP during the last 3 months, median (IQI) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–5) | |

| GP home visits in the last 3 months, n (%): | 0 | 44 (13.2) | 26 (13.4) |

| 1 | 48 (14.4) | 30 (15.5) | |

| 2 | 40 (12.0) | 30 (15.5) | |

| 3 | 49 (14.7) | 24 (12.4) | |

| >3 | 152 (45.7) | 84 (43.3) | |

| Unplanned home visits by GP, n (%): | No | 134 (49.1) | – |

| Yes | 138 (50.9) | ||

| GP gave private number to patient to use in out-of-office hours, n (%): | No | 164 (58.4) | – |

| Yes | 116 (41.6) | ||

| GP had made a plan with the patient for whom to contact in out-of-office hours: | No | 180 (63.8) | – |

| Yes | 102 (36.2) | ||

| GP had contact with relatives, n (%): | No | 39 (13.5) | – |

| Yes | 243 (86.5) | ||

| Community nurse involvement, n (%): | No | 105 (31.1) | – |

| Yes | 228 (68.9) | ||

| Specialist team involvement, n (%): | No | 206 (61.9) | – |

| Yes | 127 (38.1) | ||

| Common involvement of professionals, n (%): | GP and community nurse | 220 (66.1) | – |

| GP and specialist team | 114 (34.2) | ||

| GP, community nurse and specialist team | 96 (28.8) | ||

| Duration of palliative period related to place of death, weeks mean (95% CI): | Institution (hospital/hospice) | 17.5 (14.6 to 20.3) | – |

| Home (home, nursing home) | 17.9 (15.4 to 20.3) | ||

| Total | 17.8 (15.9 to 19.6) | ||

| Time spent at home related to place of death, weeks mean (95% CI): | Institution (hospital/hospice) | 14.6 (11.8 to 17.3) | – |

| Home (home, nursing home) | 14.5 (12.5 to 16.6) | ||

| Total | 14.6 (13.0 to 16.3) | ||

| Percentage of time spent at home related to place of death, mean, % (95% CI): | Institution (hospital/hospice) | 75.1 (71.0 to 79.1) | |

| Home (home, nursing home) | 84.0 (80.5 to 87.6) | – | |

| Total | 80.1 (77.4 to 82.8) | ||

Themes in the 72-item questionnaires included: information about closest relative and the community nurse/centre involved, GP knowledge of patient before the palliative pathway, length of the palliative period, type of contact, patient's wish for place of death, care for relatives, cooperation with other healthcare professionals, evaluation of the care provided, overall view on palliative care in primary care and demographic data of the GP's practice.

Statistically significantly different from cases in study. Not all sums of percentages equal 100.0% because of rounding off. IQI = interquartile interval.

General practices completed questionnaires for one to six patients (mean: two patients). Non-responding practices were not statistically significantly different from participating practices with respect to organisation (single or partnership), patients per GP, and number of questionnaires sent per practice (data not shown).

The 194 cases from non-responding GPs were not statistically significantly different from included cases regarding patients' sex, place of death, and number of GP home visits (Table 1). However, patients in the non-participating group were statistically significantly older.

Descriptive data

GPs were involved in 89% of the cases, knew the patient well before the palliative period (87%) and had contact with the relatives (87%). In nearly half of the cases, GPs paid at least four home visits during the last 3 months of patients' lives, and in only 13% of the cases did the GP not pay home visits at all. Likewise, in nearly half of the cases, GPs provided special services like unplanned home visits and offering their private phone numbers (Table 1).

In two-thirds of the cases GPs were involved together with community nurses, and in one-third of the cases a specialist team was involved. In 80 cases (24.0%) GPs were involved without community nurses or specialist team (Table 1).

More than half of patients died at home (one-fifth at a nursing home). However, those who eventually died at institutions spent more than 75% of their time at home during the palliative pathway (Table 1).

Association with home death

GP home visits were positively associated with facilitating home death (PR = 4.5, 95% CI = 1.3 to 15.6) This is shown in Table 2; a total of 333 cases were included in the analyses, and unadjusted and adjusted PRs are shown with 95% CIs. Home visits (no/yes) were also replaced with an ordered categorical variable (0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4), referring to the actual number of visits, in the same model (data not shown). When GPs made three or more home visits, the patient's likelihood of attaining home death increased significantly (PR for three home visits = 6.9, 95% CI = 2.0 to 23.4), PR for ≥4 home visits = 6.1 (95% CI = 1.8 to 20.0) with 0 home visits as reference group).

Table 2.

Associations between home death and model variables.

| Unadjusted PR (95% CI) | Adjusted PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of patient, years | ||

| 18–65 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥66 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7)a | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Sex of patient | ||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | ||

| Bronchus/lung | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Colon/rectum | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.8) |

| Breast | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) |

| Prostate | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8)a |

| Other | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.6) |

| Patient's marital status | ||

| Single | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Married | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Children | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes, living at home | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) |

| Yes, adults | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| GP knowledge prior to palliative period | ||

| Poor | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Well | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Home visits by GP | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 3.5 (1.9 to 6.4)a | 4.5 (1.3 to 15.6)a |

| Unplanned home visits by GP | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| GP gave private number to patient to use in out-of-office hours | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)a | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

| GP had contact with relatives | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) |

| Community nurse involvement | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2)a | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8)a |

| Specialist team involvement | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)a | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

Statistically significant. PR = prevalence ratio.

To examine the effect on the model of the inclusion of patients who died at nursing homes, the analysis was also run without cases with ‘nursing home death’. The positive association between facilitating home death, the GP making home visits (PR = 3.7, 95% CI = 1.0 to 12.9) and the involvement of community nurses (PR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.0 to 2.6) persisted for those 120 patients who died in their own home compared with those who died at an institution.

Further, involvement of community nurses (PR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.0 to 1.8) and having prostate cancer compared with lung/bronchus cancer (PR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.0 to 1.8) were just significantly positively associated with facilitating home death.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

In a consecutive group of cancer patients who died from cancer with a palliative pathway at home (including nursing home), a strong association between GP home visits and facilitating home death was found (Table 2). Further, an increased likelihood of home death was seen when GPs paid three or more home visits during the last 3 months. The association persisted when excluding the cases with death at nursing homes.

In the univariate analysis weaker but significant associations were also seen. Whenever the patients were ≥66 years of age, whenever GPs gave a private number to use in out-of-office hours, and whenever community nurses or specialist teams were involved, the chance of facilitating home death increased. However, of these, only the association between home death and involvement of the community nurse persisted in the adjusted analysis.

Strengths and limitations of the study

To eliminate differential misclassification, standardised official health registers were used to identify the study population, including places and reasons of death. However, in 25 of the cases, GPs returned the questionnaires stating that the patient did not die from cancer. These cases were defined as non-response, which may have introduced a bias (including confounding by indication), but direction and importance of this bias is hard to establish. However, no statistically significant differences were found between included and non-included cases regarding sex, place of death, and number of GP home visits. This indicated that selection bias must be limited. Furthermore, using GP-reported data causes potential information biases, and therefore data from registers were used whenever possible.

To minimise recall bias, questionnaires were sent in January 2007 instead of waiting for the Danish Register of Causes of Death to be updated in 2008. Further, all Danish GPs can consult electronic patient files when completing a questionnaire.

This study's results are generalisable to patients who had palliative home care in a Danish context. This was because patients were sampled who died from cancer and had some palliative period at home. This was regardless of the involvement of specialised teams or hospital records and because Denmark is quite homogenous with respect to primary care and social demography.

Approximately 1680 patients died from cancer in Aarhus County in 2006, and 599 cases recruited during a 9-month period were included (Figure 1). This lower amount of cases can be explained by the fact that patients aged <18 years or with non-melanoma cancer were not included. Also, only those with cancer diagnosis registered in a hospital in Aarhus County were included as the main diagnosis of admittance in a 10-year period. Furthermore, the period where patients could die (1 March to 30 November) was without the winter months of 2006, which may account for some of the missing cases, since winter months may have a higher average of deaths.

Comparison with existing literature

The found association between home death and GP home visits fits well with findings of previous studies.7,20–22 Contrary to these studies, the model was adjusted by including time at home in the palliative period. This was because dying at home often demands more home visits and more home care, and the patient has to be at home to receive these visits. The association between home death and GP home visits persisted despite this adjustment.

GPs' participation in palliative care may be seen as a package. Thus, if GPs are paying many home visits during the palliative period, this would testify to their willingness to assume different tasks and provide different services in relation to palliative pathways. However, there was a lack of insight into the precise contents of this informal, palliative healthcare package. More detailed studies should therefore be conducted to elucidate the specific effect of GP home visits and other GP-related factors. Furthermore, the high CI is a sign of uncertainty of the exact value of PR; more cases in the analysis are needed to give a more exact value.

In line with previous studies, a significant association was found between home death and involvement of community nurses.6,7,9 Since addressing this important association was not an aim of this study and the finding came from an adjustment in the analysis of community nurses' involvement, no conclusion can be made and the found association therefore deserves further investigation.

The fact that patients who received palliative care at home and died at institutions still spent most of the palliative period at home definitely questions the use of home death as a measure of good quality in terminal care. A ‘successful palliative pathway’ is a lot more than achieving home death. The reasons for hospitalisation during the last days of life may be many, and hospital death may represent successful care just as well as home death. Also, studies on terminally ill patients' preferred place of death suggest that patients' preference changes away from home death when death approaches, and that for some patients home death may not be preferred at all.1 GPs and other healthcare professionals have an important job helping patients to state a preference.23,24 Studies are therefore warranted to establish what constitutes a successful palliative pathway for patients and relatives, rather than only looking at place of death and how primary care professionals may be involved in that pathway.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

This study calls for further assessment of the predictive power of a more active approach to home visits. Furthermore, this study indicates that involvement of community nurses were independently associated with a higher likelihood of home death. The primary care team may be instrumental in allowing patients to die at home. Future research should examine the more precise mechanisms of their involvement.

Acknowledgments

Profound gratitude is extended to participating GPs.

Funding body

The study was funded by the Aarhus County Research Fund for Clinical Development and Research in General Practice and across the Primary and Secondary Health Care Sectors (4-01-3-04), the Danish National Research Foundation for Primary Care (585-457808) and the Multipractice Study Committee (585-04/2072)

Ethical approval

According to the Scientific Committee for the County of Aarhus, the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee System Act does not apply here (j.no. 2005-2.0/14). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.no. 2005-41-4967) and the Danish National Board of Health (j.no. 7-505-29-1007/1)

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(3):287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(3):245–251. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanratty B. Palliative care provided by GPs: the carer's viewpoint. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(457):653–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2002;16(6):457–464. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm573oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grande GE, Farquhar MC, Barclay SI, et al. Valued aspects of primary palliative care: content analysis of bereaved carers' descriptions. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(507):772–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukui S, Fukui N, Kawagoe H. Predictors of place of death for Japanese patients with advanced-stage malignant disease in home care settings: a nationwide survey. Cancer. 2004;101(2):421–429. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aabom B, Kragstrup J, Vondeling H, et al. Population-based study of place of death of patients with cancer: implications for GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(518):684–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515–521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howat A, Veitch C, Cairns W. A retrospective review of place of death of palliative care patients in regional north Queensland. Palliat Med. 2007;21(1):41–47. doi: 10.1177/0269216306072383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones RV, Hansford J, Fiske J. Death from cancer at home: the carers' perspective. BMJ. 1993;306(6872):249–251. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6872.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazil K, Bedard M, Krueger P, et al. Service preferences among family caregivers of the terminally ill. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):69–78. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Jensen AB, et al. Palliative care for cancer patients in a primary health care setting: bereaved relatives' experience, a qualitative group interview study. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivarius NF, Hollnagel H, Krasnik A, et al. The Danish National Health Service Register: a tool for primary health care research. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44(4):449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, et al. The Danish Civil Registration System: a cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Danish National Board of Health. The Danish register of causes of death [in Danish] 2008.

- 16.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. 1st edn. London: Hodder Arnold; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality and Quantity. 2007;41(5):673–690. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantwell P, Turco S, Brenneis C, et al. Predictors of home death in palliative care cancer patients. J Palliat Care. 2000;16(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brazil K, Bedard M, Willison K. Factors associated with home death for individuals who receive home support services: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2002;1(1):2–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G, et al. Primary care continuity and location of death for those with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(6):911–918. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munday D, Petrova M, Dale J. Exploring preferences for place of death with terminally ill patients: qualitative study of experiences of general practitioners and community nurses in England. BMJ. 2009;338:b2391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meeussen K, Van den Block L, Bossuyt N, et al. GPs' awareness of patients' preference for place of death. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(566):665–670. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]