Abstract

Objective

Both genetic and epigenetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of lupus. Herein, we study methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) polymorphism in a large cohort of lupus patients and controls, and determine functional consequences of the lupus-associated MECP2 haplotype.

Methods

We genotyped 18 SNPs within MECP2, located on chromosome Xq28, in a large cohort of European-derived lupus patients and controls. We studied the functional effects of the lupus-associated MECP2 haplotype by determining gene expression profiles in B cell lines from female lupus patients with and without the lupus-associated MECP2 risk haplotype.

Results

We confirm, replicate, and extend the genetic association between lupus and genetic markers within MECP2 in a large independent cohort of European-derived lupus patients and controls (OR= 1.35, p= 6.65×10−11). MECP2 is a dichotomous transcriptional regulator that either activates or represses gene expression. We identified 128 genes that are differentially expressed in lupus patients with the disease-associated MECP2 haplotype; most (~81%) are upregulated. Genes that were upregulated have significantly more CpG islands in their promoter regions compared to downregulated genes. Gene ontology analysis using the differentially expressed genes revealed significant association with epigenetic regulatory mechanisms suggesting that these genes are targets for MECP2 regulation in B cells. Further, at least 13 of the 104 upregulated genes are interferon-regulated genes. The disease-risk MECP2 haplotype is associated with increased expression of the MECP2 transcriptional co-activator CREB1, and decreased expression of the co-repressor HDAC1.

Conclusion

Polymorphism in the MECP2 locus is associated with lupus and, at least in part, contributes to the interferon signature observed in lupus patients.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus) is a chronic debilitating autoimmune disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The disease can affect multiple organs including the brain, kidney, lung, heart, and joints. Lupus is characterized by the production of autoantibodies to a variety of nuclear antigens and by the presence of an autoreactive T cell phenotype in the peripheral blood (1, 2). The pathogenesis of both drug-induced and idiopathic lupus involves a defect in T cell DNA methylation resulting in overexpression of a number of methylation sensitive genes such as ITGAL (CD11a), TNFSF7 (CD70), PRF1 (perforin), and CD40LG (CD40L) (3, 4). Normal CD4+ T cells treated with DNA methylation inhibitors such as 5-azaC overexpresses the same methylation sensitive genes similar to T cells from lupus patients. T cells treated with DNA methylation inhibitors become autoreactive in vitro; capable of spontaneously lysing syngeneic macrophages, and inducing autologous B cell activation and immunoglobulin production (5). Further, T cells treated with DNA methylation inhibitors induce a lupus-like disease with glomerulonephritis and autoantibody production upon adoptive transfer into mice (6). Interestingly, a CD4+ T cell methylation defect has also been reported in at least one murine model of the disease (7).

We have previously reported the genetic association between lupus and common variants within the methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene in two independent cohorts of lupus patient and controls and identified both risk and protective haplotypes (8). MECP2, located on chromosome Xq28, encodes for a 486 amino acid protein that binds methylated DNA and is intimately involved in the transcriptional regulation of methylation-sensitive genes.

MECP2 had been largely thought of as a transcriptional repressor exerting its effects, at least in part, by recruiting histone deacetylases to promoter sequences of target genes, thereby inducing a transcriptionally inaccessible chromatin configuration (9). Recent evidence, however, indicates that MECP2 is also a transcriptional activator capable of recruiting the transcription factor CREB1 (10). Indeed, MECP2 acts as a transcriptional activator in the majority (~85%) of genes regulated by MECP2 in the murine hypothalamus (10).

In this report, we first confirm the association of lupus with variants within MECP2 in a large independent cohort of European-derived lupus patients and controls. We next determined the expression of the two known mRNA isoforms of MECP2 in B cell lines from lupus patients with the risk and the protective haplotypes. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the MECP2 risk haplotype dictates global changes in B cell gene expression relative to the protective non-risk haplotype and thereby provides multiple paths toward realization of the phenotype.

Methods

Patients and controls

A cohort of 1,418 European-derived unrelated lupus patients and 1,876 race-matched controls were recruited at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation as well as at collaborating institutes in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. This cohort is independent of the previously studied European-derived cohort reported in Sawalha et al (8). All patients met the 1997 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for lupus. All protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Genotyping of 18 SNPs within the MECP2 gene was performed using an Illumina BeadStation 500GX instrument using Illumina Infinum II genotyping assays following manufacturer’s recommendations. These 18 SNPs were selected from the published SNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) to cover the entire length of MECP2, and were previously genotyped by our group in two independent cohorts of lupus patients and controls.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of genotyping data

SNPs with minor allele frequencies of ≥ 5% and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p value of >0.01 were used for further analysis. All SNPs analyzed had a genotyping success rate of ≥97.4%. Allele frequencies were determined in both cases and control groups, and a Pearson’s Chi square and p value were calculated to assess differences between the two groups. Permutation p values were calculated using Haploview 4.1 to correct for multiple testing (11). Haploview 4.1 was also used to generate a linkage disequilibrium (LD) plot for the analyzed SNPs and to calculate correlation coefficient (r2) values between SNPs. Common haplotypes (with a frequency of >1%) produced by the disease-associated SNPs were determined and haplotype frequencies calculated using Haploview 4.1. Principal component analyses (PCA) were computed to identify populations substratification in our cohort (12). A total of 64 samples that violated the assumption of sample homogeneity based on the PCA (41 cases and 23 controls) were removed prior to data analysis. We then performed genomic control analysis to calculate the inflation factor λ (Lambda) using 2218 null SNPs, which produced a λ =1.04, further indicating no evidence for population substratification. The inflation factor is a measure that quantifies the degree to which population stratification increases the chi2 test statistics.

Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis of Microarray Data

Statistical analysis of microarray data was performed using associative analysis of expression as previously described (13). CpG islands in the 5kb upstream and 5kb downstream regions of the transcription start site of differentially expressed genes were identified algorithmically using Build 36.3 (released Mar 24, 2008) of the Human genome (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/H_sapiens/). CpG islands were defined as a stretch of DNA of at least 200bp with a C+G content of at least 50% and an observed/expected CG frequency of at least 0.6. The IRIDESCENT algorithm (14) was used to identify and score the relevance of “objects” (i.e., genes, diseases, phenotypes, small molecules and ontology categories) that co-occurred in MEDLINE abstracts with the differentially expressed genes. Names and synonyms for these objects are obtained from publicly available databases including, but not limited to, OMIM (diseases), Disease Ontology Database (phenotypes), Entrez Gene (genes), CHEMID (chemicals) and the Gene Ontology database (GO categories). A shared relationship between a subset of differentially expressed genes and another object in the IRIDESCENT database identifies common processes and associations.

Cell culture and RNA extraction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transformed B cell lines from lupus patients were used to study the effect of MECP2 risk and protective haplotypes. B cell lines were prepared from PBMCs isolated from lupus patients by density gradient centrifugation and then suspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% bovine serum, supplemental glutamine, streptomycin, and penicillin. A small concentration of cyclosporine is added (1 μg/ml) to inhibit T cell suppression of transformed B cell growth. Finally, an aliquot of a fresh culture supernatant from a B95-8 marmoset cell line culture producing infectious Epstein-Barr virus is added as the transforming agent. Cell lines grow in a few weeks, are expanded, and frozen in 90% fetal calf serum and 10% DMSO in aliquots of 20 million cells at −70°C. After having equilibrated at this temperature the cells are transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage. EBV transformed B cell lines from 10 lupus patients homozygous for the MECP2 risk haplotype and 10 lupus patients homozygous for the protective haplotypes were thawed into medium, washed and grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, glutamine, streptomycin and penicillin. Twenty-four hours prior to isolating RNA all cell lines were washed and grown into fresh media. RNA was isolated using a combination of Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Briefly, 15×106 cells were lysed in 1 ml of Trizol reagent, 200μl of chloroform added, then mixed by inversion for 15 seconds and incubated at room temperature for 3 minutes. The lysate was then centrifuged for 15 minutes at 4°C and 14,000 RPM. Ethanol (100%) was added to the supernatant at 0.53 volume and the mixture loaded into the RNeasy column and RNA isolation was completed following the RNeasy protocol.

Real time RT PCR

To measure the levels of MECP2 transcripts (isoform 1 and isoform 2), real time RT PCR was performed using iScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit With SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the Rotor-Gene 3000 real-time thermocycler (Corbett Research, Australia). RNA was first treated with Turbo DNA-free (Ambion, Austin, TX) to digest any contaminating DNA. A total of 62.5ng RNA was used per reaction. The following PCR protocol was used: 10 min at 50 °C, 5 min at 95 °C, 45 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C. Internal standards prepared by serial dilutions were used to quantify expression levels of both MECP2 isoforms, CREB1, and HDAC1, followed by normalization to a housekeeping gene (GAPDH or ACTB (β actin)). The following primers were used: MECP2A (isoform 1) forward: 5′-CTGGGATGTTAGGGCTCAGGGA-3′, reverse: 5′-AGAGTGGTGGGCTGATGGCT-3′; MECP2B (isoform 2) forward: 5′-AGGCGAGGAGGAGAGACTGGAA-3′, reverse: 5′-AGAGTGGTGGGCTGATGGCT-3′; CREB1 forward: 5′-CCAGCAGAGTGGAGATGCAG-3′, reverse: 5′-GTTACGGTGGGAGCAGATGAT-3′; HDAC1 forward: 5′-ACCCGGAGGAAAGTCTGTTAC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGTAGAGACCATAGTTGAGCAGC-3′; GAPDH forward: 5′-TGTTGCCATCAATGACCCCTTC-3′, reverse: 5′-CTCCACGACGTACTCAGCGC-3′; ACTB forward: 5′-GCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAGC-3′; reverse: 5′-GGATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC -3′. Real time RT PCR as described above was also used to validate the expression microarray data. Genes examined include CLIC2, IFITM3, IGJ, ITM2B, and TEX15. Primer sequences are available upon request. All primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

Expression microarray

After purification, RNA concentration was determined with a Nanodrop scanning spectrophotometer, and then qualitatively assessed for degradation using the ratio of 28:18s rRNA using a capillary gel electrophoresis system (Agilent 2100 Bionalalyzer, Agilent Technologies). Biotinylated amplied RNA was produced from 250ng total RNA per sample using a modification of the Eberwine protocol (15) as described in the Illumina® TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit from Ambion, Inc (Austin, TX). Briefly, RNA was reverse-transcribed with oligo(dT) primer containing a T7 promoter. RNA containing biotin-UTP ribonucleotides was amplified by in vitro transcription to generate anti-sense RNA. This RNA was hybridized overnight at 58C to human WG-6 version 3 Expression BeadChip™ microarrays (Illumina Corp, San Diego, CA). These arrays contain 48,804 50-mer oligonucleotide probes coupled to beads that are mounted on glass slides. Each bead has approximately a 20–30-fold redundancy per microarray. Microarrays are washed under high stringency, labeled with streptavidin-Cy3, and scanned with an Illumina BeadStation 500 scanner.

Results

Lupus is associated with polymorphisms within the MECP2 gene

We confirm the association between SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) within MECP2 and lupus in a large independent cohort of European-derived lupus patients and controls. We genotyped 18 SNPs within MECP2 in a cohort of 1,418 European-derived lupus patients and 1,876 controls. Principle component analysis was used to detect population substratification and identified ‘outlier’ samples (41 cases and 23 controls) that were excluded from further analysis. A total of 1,377 lupus patients (1,293 females, and 84 males) and 1,853 controls (1,097 females, and 756 males) were analyzed.

SNPs with minor allele frequencies of ≥ 5%, and a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p value of >0.01 were included in subsequent analysis. HWE p value measures the difference between the observed genotype frequency and the expected genotype frequency based on the observed allele frequency. A high HWE p value indicates random mating in a study population. We confirm the association between lupus and all 8 SNPs within MECP2 previously reported in European-derived and Korean lupus patients and controls (8). Indeed, the SNPs with the strongest association rs3027933, rs1734791, rs1734792, rs1734787, and rs2075596, have odds ratios of 1.38, 1.37, 1.37, 1.35, and 1.35, respectively, and p values of 1.50×10−5, 1.92×10−5, 2.80×10−5, 5.22 × 10−5, and 5.66 ×10−5, respectively in the new independent cohort (Table 1). All the 8 lupus-associated SNPs identified are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with pair-wise r2 values of ≥0.64. The SNPs with the strongest association, mentioned above, are in strong LD with pair-wise r2 values of ≥0.95 suggesting that they are surrogates for the same genetic effect.

Table 1.

Genetic association between SNPs within MECP2 and lupus in an independent European-derived lupus patients and controls. Only SNPs with minor allele frequencies of ≥5% were analyzed.

| SNP | Risk allele | Risk allele frequency | Chi2 | OR (95% CI) | p value | Permutation p value | HWE p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | |||||||

| rs2075596 | A | 446 (16.8) | 383 (13.0) | 16.212 | 1.35 (1.17–1.57) | 5.66×10−5 | 0.0003 | 0.25 |

| rs3027933 | C | 464 (17.4) | 390 (13.2) | 18.734 | 1.38 (1.19–1.60) | 1.50×10−5 | 1.00E-04 | 0.28 |

| rs3027935 | G | 2476 (93.3) | 2721 (92.4) | 1.581 | 1.14 (0.93–1.40) | 0.2086 | 0.5385 | 0.76 |

| rs3027939 | A | 2447 (94.8) | 2721 (93.9) | 1.828 | 1.17 (0.93–1.48) | 0.1763 | 0.4747 | 0.99 |

| rs17435 | T | 608 (22.8) | 575 (19.5) | 9.005 | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 0.0027 | 0.0136 | 0.79 |

| rs7050901 | G | 2542 (95.2) | 2786 (94.5) | 1.534 | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 0.2155 | 0.5508 | 0.98 |

| rs1624766 | G | 604 (22.7) | 576 (19.5) | 8.4 | 1.21 (1.06–1.37) | 0.0038 | 0.0176 | 0.96 |

| rs7884370 | A | 2523 (94.7) | 2773 (94.0) | 1.198 | 1.14 (0.90–1.43) | 0.2737 | 0.6497 | 0.75 |

| rs1734787 | C | 459 (17.2) | 393 (13.3) | 16.366 | 1.35 (1.17–1.56) | 5.22×10−5 | 0.0003 | 0.40 |

| rs5987201 | G | 2529 (94.8) | 2772 (94.0) | 1.655 | 1.16 (0.92–1.46) | 0.1982 | 0.5189 | 1.00 |

| rs1734791 | A | 464 (17.5) | 395 (13.4) | 18.269 | 1.37 (1.18–1.59) | 1.92×10−5 | 0.0002 | 0.24 |

| rs1734792 | A | 462 (17.3) | 392 (13.3) | 17.546 | 1.37 (1.18–1.58) | 2.80×10−5 | 0.0003 | 0.31 |

| rs11156611 | G | 2530 (94.8) | 2773 (94.0) | 1.387 | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) | 0.239 | 0.5891 | 1.00 |

| rs2239464 | A | 583 (21.9) | 541 (18.4) | 10.811 | 1.25 (1.09–1.42) | 0.001 | 0.0053 | 0.94 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Using the 8 SNPs in MECP2 that are associated with lupus in our cohort, we identified 3 haplotypes with a frequency of >1%. Haplotype 1 “ACTGCAAA” is a disease-risk haplotype (OR= 1.38, 95%CI= 1.19–1.60, p= 2.36×10−5) while Haplotype 2 “GGAAATCG” is a protective haplotype (OR= 0.82, 95%CI= 0.72–0.93, p= 0.0022). These data are consistent with and confirm our previously reported findings (8).

Table 2 summarizes the odds ratios and the Fisher’s combined p values for the MECP2 SNPs associated with lupus in three independent cohorts of lupus patients and controls that have been studied to date. MECP2 SNPs with the strongest association are rs1734787, rs1734792, and rs1734791, with Fisher’s combined p values of 6.65×10−11, 9.67×10−11, and 1.52×10−10, respectively.

Table 2.

Fisher’s combined p values for risk alleles in lupus-associated MECP2 SNPs in all three lupus cohorts reported.

| SNP | Risk allele | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Fisher combined p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean* | European-derived 1* | European-derived 2** | |||

| rs2075596 | A | 1.49 (1.24–1.80) | 1.28 (1.09–1.52) | 1.35 (1.17–1.57) | 1.57×10−9 |

| rs3027933 | C | 1.48 (1.23–1.79) | 1.30 (1.10–1.53) | 1.38 (1.19–1.60) | 2.90×10−10 |

| rs17435 | T | 1.58 (1.31–1.90) | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 1.45×10−9 |

| rs1624766 | G | 1.50 (1.24–1.82) | 1.28 (1.10–1.48) | 1.21 (1.06–1.37) | 3.76×10−8 |

| rs1734787 | C | 1.55 (1.29–1.87) | 1.32 (1.12–1.56) | 1.35 (1.17–1.56) | 6.65×10−11 |

| rs1734791 | A | 1.51 (1.25–1.82) | 1.31 (1.11–1.54) | 1.37 (1.18–1.59) | 1.52×10−10 |

| rs1734792 | A | 1.53 (1.27–1.83) | 1.31 (1.11–1.54) | 1.37 (1.18–1.58) | 9.67×10−11 |

| rs2239464 | A | 1.51 (1.25–1.82) | 1.24 (1.07–1.45) | 1.25 (1.09–1.42) | 2.92×10−8 |

Cohorts published in Sawalha AH et al. 2008 (8). The Korean cohort included 628 lupus patients and 736 controls; European-derived 1 cohort included 1,080 patients and 1,080 controls.

Current study. The European-derived 2 cohort included 1,377 lupus patients and 1,853 controls.

Expression of MECP2 in lupus patients with and without the lupus-associated haplotype

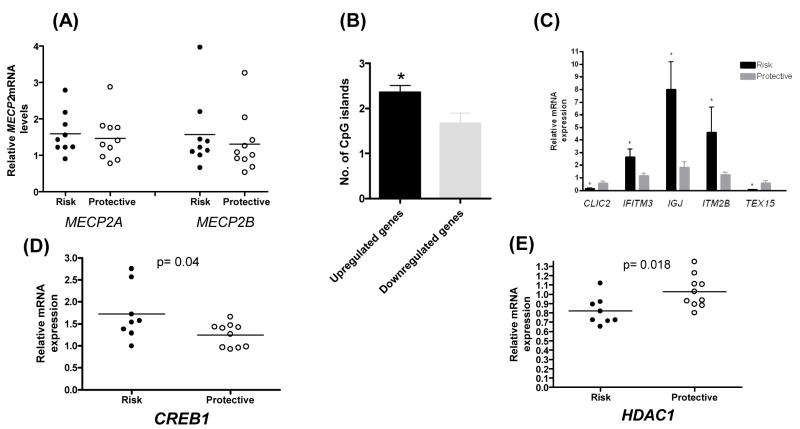

To determine if the disease-associated polymorphism within the MECP2 locus alters the expression of MECP2, we determined the expression of the two known MECP2 transcript isoforms (MECP2A and MECP2B) in female lupus patients who are homozygous for the disease risk haplotype and in female lupus patients homozygous for the protective haplotype. MECP2A (isoform 1) includes exon 2 where translation is reported to start. The more recently identified transcript variant, MECP2B (isoform 2), lacks exon 2, and has a translation start site in the first exon (16, 17). There was no detectable difference in the level of either transcript variant in lupus patients with the risk haplotype compared to lupus patients with the protective haplotype as measured by real time RT PCR and primers specific for the two transcript isoforms (Fig. 1A). However, statistical power to find differences in this experiment is limited by the number of B cell lines available with the risk and protective homozygous MECP2 haplotypes.

Fig. 1.

(A) mRNA expression levels of MECP2 transcript variants (MECP2A and MECP2B) in B cells from lupus patients homozygous for the MECP2 risk haplotype (Risk) compared to patients homozygous for the protective haplotype (Protective). (B) Genes that are upregulated (104 genes) in lupus patients with the disease-associated MECP2 haplotype have significantly more CpG islands in their promoter region compared to downregulated genes (24 genes) (t= 2.07, p=0.04). (C) Confirmation of expression micraoarray data by real time RT PCR. The expression of 5 genes differentially expressed in B cells from 5 patients with the MECP2 risk haplotype (Risk) compared to 6 patients with the MECP2 protective haplotype (Protective) (p<0.05). (D, E) mRNA expression levels of CREB1 and HDAC1 in B cells from lupus patients homozygous for the MECP2 risk haplotype (Risk) compared to patients homozygous for the protective haplotype (Protective).

Identification of functional consequences of the disease-associated MECP2 haplotype

MECP2 binds methylated DNA, recruits histone deacetylase or CREB1, and functions as a transcriptional repressor or activator for genes with CG-rich promoter sequences. Therefore, if the lupus-risk MECP2 haplotype we identified alters the function of MECP2, it is likely to affect the expression of a number of target genes that are regulated by MECP2. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expression patterns of genes in B cell lines from five European-derived female lupus patients homozygous for the disease-risk haplotype compared to six European-derived female lupus patients homozygous for the protective haplotype using expression microarrays. We identified 128 genes that are differentially expressed as a result of the MECP2 haplotype (Table 3 and Table 4). The majority of differentially expressed genes (104 genes, ~81%) are upregulated (≥1.5 fold) in patients with the risk haplotype compared to patients with the protective haplotype, while 24 genes (~19%) were downregulated. Interestingly, the number of CpG islands in the 5kb region upstream and 5kb region downstream of the transcription start site was significantly higher in the upregulated genes compared to genes that are downregulated (t=2.07, df=120, p=0.04) (Fig. 1B). A number of genes that are upregulated in patients with the MECP2 risk haplotype are interferon-regulated genes. These include BTN3A2, CEBPD, CECR1, IFI6 (G1P3), IFI35, IFITM1, IFITM3, IRF7, ISG20, LY6E, PHGDH, S100A10, and ZBP1. An interferon signature is well documented in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of lupus patients (18, 19). We conducted a literature-based analysis of shared commonalities for these genes as previously described (14), and found that several of these genes are associated with epigenetic mechanisms (Table 5). We confirmed the microarray data by examining the expression of 5 genes (3 upregulated and 2 down regulated) using real time RT PCR. The genes examined are CLIC2, IFITM3, IGJ, ITM2B, and TEX15 (Fig. 1C). We next determined mRNA expression levels of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and CREB1 in patients homozygous for the disease-risk compared to patients homozygous for the protective haplotype. HDAC1 and CREB1 are recruited by MECP2 and function as a transcriptional co-repressor and a transcriptional co-activator, respectively. We found that the presence of the lupus-risk MECP2 haplotype is associated higher expression levels of CREB1 (0.04) and lower expression levels of HDAC1 (p=0.018) and (Fig. 1D, 1E).

Table 3.

Genes upregulated (≥1.5 fold) in lupus patients homozygous for the lupus-associated MECP2 risk haplotype as compared to lupus patients homozygous for the MECP2 protective haplotype

| Gene | Definition/Description | Ratio Risk/Protective | Associative P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES | Amino-terminal enhancer of split, transcript variant 3 | 1.55 | 5.63×10−09 |

| AIM2 | Absent in melanoma 2 | 1.62 | 9.06×10−06 |

| ANG | Angiogenin, ribonuclease, RNase A family, 5 | 1.71 | 3.85×10−05 |

| ARSD | Arylsulfatase D, transcript variant 1 | 1.54 | 2.47×10−18 |

| B3GALT4 | UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,3-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide 4 | 1.58 | 1.69×10−21 |

| BTG2 | BTG family, member 2 | 1.77 | 2.07×10−34 |

| BTN3A2 | Butyrophilin, subfamily 3, member A2 | 1.78 | 8.00×10−07 |

| BTN3A3 | Butyrophilin, subfamily 3, member A3, transcript variant 1 | 1.59 | 1.76×10−19 |

| C19ORF10 | Chromosome 19 open reading frame 10 | 1.50 | 1.28×10−13 |

| CCDC53 | Coiled-coil domain containing 53 | 1.77 | 1.31×10−05 |

| CCR6 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 6, transcript variant 2 | 2.53 | 1.76×10−19 |

| CD1C | CD1C antigen, c polypeptide | 1.52 | 1.47×10−08 |

| CD79A | CD79A antigen (immunoglobulin-associated alpha), transcript variant 1 | 2.16 | 4.05×10−20 |

| CD96 | CD96 molecule, transcript variant 1 | 1.89 | 1.69×10−40 |

| CD96 | CD96 molecule, transcript variant 2 | 1.62 | 3.59×10−37 |

| CDKN2C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C, transcript variant 2 | 1.70 | 7.19×10−05 |

| CEBPD | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), delta | 1.91 | 6.19×10−38 |

| CECR1 | Cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 1, transcript variant 1 | 3.01 | 1.35×10−33 |

| CHST12 | Carbohydrate (chondroitin 4) sulfotransferase 12 | 1.56 | 4.86×10−05 |

| CLEC2D | C-type lectin domain family 2, member D, transcript variant 3 | 1.86 | 1.38×10−06 |

| CRIM1 | Cysteine rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 (chordin-like) | 1.51 | 2.74×10−09 |

| CRKRS | Cdc2-related kinase, arginine/serine-rich | 2.23 | 7.28×10−10 |

| DHRS8 | Hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 11 | 1.58 | 3.14×10−28 |

| EAF2 | ELL associated factor 2 | 1.70 | 2.97×10−07 |

| EDG6 | Endothelial differentiation, G-protein-coupled receptor 6 | 2.04 | 5.91×10−09 |

| EVI2B | Ecotropic viral integration site 2B | 1.75 | 6.98×10−18 |

| FAM46C | Family with sequence similarity 46, member C | 2.92 | 9.17×10−20 |

| FAM55C | Family with sequence similarity 55, member C | 1.62 | 1.42×10−08 |

| FLJ11000 | Hypothetical protein FLJ11000 | 2.26 | 4.20×10−28 |

| FLJ20021 | PREDICTED: Hypothetical LOC90024 | 1.52 | 8.68×10−09 |

| FLJ43692 | ARHGEF5-like | 1.83 | 4.81×10−05 |

| G1P3 | Interferon, alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-6-16), transcript variant 1 | 1.53 | 3.20×10−05 |

| GPR18 | G protein-coupled receptor 18 | 2.02 | 1.92×10−10 |

| GSDML | Gasdermin-like | 1.76 | 6.37×10−114 |

| H2AFJ | H2A histone family, member J, transcript variant 2 | 1.66 | 2.26×10−04 |

| HCST | Hematopoietic cell signal transducer, transcript variant 1 | 1.64 | 4.50×10−04 |

| HIST1H1C | Histone cluster 1, H1c | 2.03 | 2.82×10−07 |

| HIST1H2BH | Histone cluster 1, H2bh | 1.52 | 1.41×10−12 |

| HIST1H4K | Histone cluster 1, H4k | 1.69 | 2.71×10−06 |

| HLA-E | Histocompatibility complex, class I, E | 1.77 | 1.01×10−17 |

| HLA-F | Major histocompatibility complex, class I, F | 1.75 | 2.64×10−45 |

| HLA-H | Major histocompatibility complex, class I, H | 2.33 | 1.21×10−09 |

| HS.276808 | CDNA FLJ43371 fis, clone NTONG2005969 | 1.63 | 1.30×10−06 |

| HS.487766 | CDNA clone L17N670205n1-10-D09 5 | 1.78 | 3.46×10−09 |

| IFI35 | Interferon-induced protein 35 (IFI35), mRNA. | 1.53 | 1.73×10−04 |

| IFI6 | Interferon, alpha-inducible protein 6 (IFI6), transcript variant 2 | 2.13 | 4.86×10−05 |

| IFITM1 | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 | 2.03 | 1.03×10−05 |

| IFITM3 | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 | 3.41 | 0.00 |

| IGJ | Immunoglobulin J polypeptide | 2.89 | 8.82×10−21 |

| IRF7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7, transcript variant b | 1.87 | 2.13×10−14 |

| IRF7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7, transcript variant c | 1.77 | 2.86×10−18 |

| ISG20 | Interferon stimulated exonuclease gene 20kDa | 2.00 | 5.27×10−08 |

| ITGAL | Integrin, Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1; alpha polypeptide | 1.87 | 2.43×10−15 |

| ITM2B | Integral membrane protein 2B | 3.15 | 2.78×10−46 |

| ITM2C | Integral membrane protein 2C, transcript variant 2 | 1.66 | 2.92×10−04 |

| ITM2C | Integral membrane protein 2C, transcript variant 1 | 1.58 | 1.09×10−03 |

| KIAA0125 | KIAA0125 | 2.47 | 6.86×10−16 |

| LBA1 | PREDICTED: Lupus brain antigen 1 | 1.72 | 1.59×10−08 |

| LDLR | Low density lipoprotein receptor (familial hypercholesterolemia) | 1.71 | 2.35×10−10 |

| LIME1 | Lck interacting transmembrane adaptor 1 | 1.76 | 2.69×10−21 |

| LMBRD1 | LMBR1 domain containing 1 | 1.57 | 1.62×10−05 |

| LMO4 | LIM domain only 4 | 1.80 | 1.67×10−05 |

| LOC387882 | Hypothetical protein | 1.60 | 4.73×10−08 |

| LOC541471 | PREDICTED: Hypothetical LOC541471 | 1.71 | 3.16×10−17 |

| LOC554223 | PREDICTED: Hypothetical LOC554223, transcript variant 3 | 1.57 | 3.18×10−24 |

| LY6E | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | 1.82 | 1.44×10−04 |

| MGC13057 | Hypothetical protein MGC13057 | 2.56 | 3.06×10−07 |

| MGC24039 | Hypothetical protein MGC24039 | 1.68 | 4.01×10−13 |

| MGC29506 | Hypothetical protein MGC29506 | 1.74 | 1.33×10−15 |

| MGST3 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 | 1.60 | 4.75×10−06 |

| MID1IP1 | MID1 interacting protein 1 (gastrulation specific G12-like (zebrafish)) | 1.50 | 3.35×10−07 |

| NCF4 | Neutrophil cytosolic factor 4, 40kDa, transcript variant 1 | 1.85 | 6.11×10−61 |

| NPC2 | Niemann-Pick disease, type C2 | 1.54 | 6.04×10−07 |

| P2RY5 | Purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 5 | 2.59 | 5.91×10−07 |

| PHGDH | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | 1.54 | 6.46×10−06 |

| PIM2 | Pim-2 oncogene | 1.61 | 4.07×10−17 |

| PIP3-E | Phosphoinositide-binding protein PIP3-E | 2.30 | 4.37×10−06 |

| PNOC | Prepronociceptin | 1.75 | 7.40×10−16 |

| PRDM1 | PR domain containing 1, with ZNF domain, transcript variant 1 | 1.67 | 1.42×10−06 |

| PRDX4 | Peroxiredoxin 4 | 1.52 | 1.01×10−12 |

| PTPRCAP | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C-associated protein | 1.68 | 1.55×10−07 |

| PYCARD | PYD and CARD domain containing, transcript variant 3 | 1.54 | 4.76×10−04 |

| RABAC1 | Rab acceptor 1 (prenylated) | 1.54 | 1.09×10−09 |

| RNASET2 | Ribonuclease T2 | 1.94 | 2.42×10−06 |

| RNF36 | Ring finger protein 36, transcript variant b | 2.00 | 8.84×10−12 |

| RNF36 | Ring finger protein 36, transcript variant a | 1.72 | 2.74×10−10 |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium binding protein A10 | 2.42 | 1.76×10−15 |

| SCOTIN | Scotin | 1.61 | 3.53×10−13 |

| SGK | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase | 2.08 | 3.28×10−04 |

| SLC27A3 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 3 | 1.62 | 9.09×10−09 |

| SORT1 | Sortilin 1 | 1.62 | 1.81×10−10 |

| SPRY2 | Sprouty homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 1.63 | 3.95×10−07 |

| SSR4 | Signal sequence receptor, delta (translocon-associated protein delta) | 1.67 | 3.93×10−10 |

| ST3GAL1 | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 1, transcript variant 2 | 1.85 | 4.02×10−36 |

| TBX15 | T-box 15 | 1.66 | 1.33×10−12 |

| TCL6 | T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 6, transcript variant TCL6d1 | 1.54 | 2.56×10−29 |

| TMEM156 | Transmembrane protein 156 | 1.50 | 3.11×10−07 |

| TNFRSF17 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 17 | 1.50 | 8.82×10−08 |

| TNFRSF7 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 7 | 2.43 | 2.91×10−07 |

| TRIB1 | Tribbles homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 1.57 | 5.01×10−05 |

| TRIM69 | Tripartite motif-containing 69, transcript variant b | 1.90 | 5.28×10−11 |

| TXNDC11 | Thioredoxin domain containing 11 | 1.66 | 1.90×10−05 |

| TXNDC5 | Thioredoxin domain containing 5, transcript variant 1 | 1.82 | 4.20×10−08 |

| VIM | Vimentin | 2.03 | 3.97×10−06 |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1, transcript variant 1 | 1.90 | 2.44×10−10 |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1, transcript variant 2 | 1.87 | 2.73×10−08 |

| ZBP1 | Z-DNA binding protein 1 | 2.09 | 1.96×10−25 |

| ZFP36 | Zinc finger protein 36, C3H type, homolog (mouse) | 1.77 | 1.04×10−31 |

| ZSWIM6 | PREDICTED: Zinc finger, SWIM-type containing 6 | 1.52 | 2.05×10−05 |

Table 4.

Genes downregulated (≥1.5 fold) in lupus patients homozygous for the lupus-associated MECP2 risk haplotype as compared to lupus patients homozygous for the MECP2 protective haplotype

| Gene | Definition/Description | Ratio Risk/Protective | Associative P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP3M2 | Adaptor-related protein complex 3, mu 2 subunit | 0.64 | 2.81×10−06 |

| CD80 | CD80 antigen (CD28 antigen ligand 1, B7-1 antigen) | 0.62 | 3.12×10−08 |

| CLIC2 | Chloride intracellular channel 2 | 0.53 | 1.96×10−09 |

| CRY1 | Cryptochrome 1 (photolyase-like) | 0.53 | 3.97×10−51 |

| FUCA1 | Fucosidase, alpha-L- 1, tissue | 0.63 | 1.77×10−04 |

| GCET2 | Germinal center expressed transcript 2, transcript variant 2 | 0.57 | 1.86×10−05 |

| HDGFRP3 | Hepatoma-derived growth factor, related protein 3 | 0.58 | 3.68×10−27 |

| HRASLS3 | HRAS-like suppressor 3 | 0.61 | 5.99×10−08 |

| HSPA4L | Heat shock 70kDa protein 4-like | 0.65 | 1.34×10−10 |

| KDELC2 | KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu) containing 2 | 0.63 | 7.11×10−34 |

| LOC134147 | Similar to mouse 2310016A09Rik gene | 0.52 | 1.29×10−07 |

| LRPPRC | Leucine-rich PPR-motif containing | 0.66 | 3.97×10−25 |

| MYC | V-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (avian) | 0.63 | 1.87×10−07 |

| PEG10 | Paternally expressed 10, transcript variant 1 | 0.66 | 1.95×10−10 |

| PRRT3 | Proline-rich transmembrane protein 3 | 0.64 | 1.17×10−05 |

| RASGRP1 | RAS guanyl releasing protein 1 (calcium and DAG-regulated) | 0.58 | 6.84×10−11 |

| RPS7 | Ribosomal protein S7 | 0.66 | 7.04×10−04 |

| SACS | Spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (sacsin) | 0.64 | 7.06×10−42 |

| SMARCA2 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 2, transcript variant 2 | 0.59 | 4.75×10−07 |

| SORD | PREDICTED: Sorbitol dehydrogenase | 0.64 | 2.77×10−05 |

| STEAP3 | STEAP family member 3, transcript variant 2 | 0.64 | 1.25×10−06 |

| TEX15 | Testis expressed sequence 15 | 0.50 | 5.83×10−62 |

| TGFBR3 | Transforming growth factor, beta receptor III | 0.48 | 7.92×10−13 |

| TMOD1 | Tropomodulin 1 | 0.50 | 6.25×10−06 |

Table 5.

IRIDESCENT algorithm analysis showing shared relationships identified in MEDLINE with genes that are differentially expressed as a result of the MECP2 haplotype present. The ratio of observed to expected relationships (Obs/Exp) is given below, which reflects a statistical enrichment score for the association. The empirically determined average Obs/Exp ratio for a list of 128 genes is 1.42 ± 0.07. Only associations greater than 3 standard deviations were reported.

| Shared relationship | Genes shared | Obs/Exp |

|---|---|---|

| Histone deacetylase | 14 | 2.48 |

| BDNF | 13 | 2.12 |

| Interferon-inducible | 13 | 4.53 |

| Chromatin structure | 12 | 2.15 |

| CREB1 | 12 | 2.03 |

| Hypermethylation | 11 | 2.36 |

| Trichostatin A | 11 | 2.83 |

| CpG methylation | 9 | 3.61 |

| Promoter methylation | 8 | 2.69 |

| Aberrant methylation | 7 | 3.61 |

Discussion

We first replicate the association between SNPs within the MECP2 gene and systemic lupus erythematosus in an independent large cohort of European-derived lupus patients and controls (Table 2). Similarly, using this independent European-derived cohort, we further confirm the previously identified MECP2 lupus risk haplotype “ACTGCAAA” and the protective haplotype “GGAAATCG”.

To study the functional consequences of MECP2 polymorphism upon lupus susceptibility, we used transformed B cell lines from lupus patients that are homozygous for the MECP2 risk haplotype and lupus patients that are homozygous for the MECP2 protective haplotype. This approach has the advantage of removing any potential confounding effects of environmental factors or medication experiences among lupus patients. We observe no difference in the steady state mRNA levels of the two known MECP2 transcript variants between lupus patients with the risk and protective haplotypes. MECP2 binds to methylated CG dinucleotides in promoter sequences of methylation sensitive genes and functions as a key transcriptional repressor, in part by recruiting histone deacetylases thereby altering chromatin configuration to a transcriptionally inaccessible form (9, 20).

Surprisingly, recent evidence suggests that MECP2 is a key transcriptional activator that associates with the transcription factor CREB1 in promoter sequences of MECP2-activated genes (10). Moreover, MECP2 is directly involved in the activation of the transcription factor CREB1. Indeed, MECP2 functions as a transcriptional activator in the majority of genes dysregulated in the hypothalamus of MECP2-transgenic and Mecp2-null mice (10). MECP2 target genes are tissue specific, perhaps related to the relative abundance of the various co-repressors or co-activators that facilitate the effects of MECP2. Given the dichotomous effects of MECP2 on gene expression, we determined the functional consequences of the lupus-risk MECP2 haplotype compared to the lupus-protective MECP2 haplotype in B cell lines from lupus patients using expression microarrays. We identified 128 genes that were differentially expressed as a result of the MECP2 haplotype carried. Interestingly, the majority of the differentially expressed genes (~81%) are upregulated in lupus patients homozygous for the risk haplotype. Approximately 85% of genes regulated by MECP2 in the hypothalamus are overexpressed in MECP2-transgenic mice and underexpressed in Mecp2-null mice (10). If this relationship remains true in human B cells, then the lupus-associated MECP2 polymorphism is surrogate for a gain of MECP2 function. This hypothesis will more readily explain the predominance of lupus in females, who have a copy of MECP2 on each of the 2 X chromosomes coupled with reactivation of the normally inactive X chromosome due to defective DNA methylation that has been described in lupus patients (21). Genes that are upregulated in patients homozygous for the risk haplotype contain significantly more CpG islands in their promoter regions compared to downregulated genes (p=0.04) (Fig. 1B). This is consistent with a gain of MECP2 function as a result of the MECP2 risk haplotype, as genes that are activated by MECP2 were reported to contain more CpG islands compared to genes repressed by MECP2 (10). The expression of CREB1 is increased in patients with the MECP2 risk haplotype as compared to patients with the protective haplotype. On the contrary, the expression of HDAC1, which is an important MECP2 transcriptional co-repressor, is decreased. This predicts that the MECP2 disease-risk haplotype induces an overall overexpression of MECP2 regulated genes, consistent with the results of our expression microarray experiment.

Gene ontology analysis reveals several interesting features in the group of genes that are differentially expressed as a result of MECP2 haplotypes. A number of genes upregulated in B cell lines carrying the risk haplotype are interferon-regulated genes. This is particularly interesting since upregulation of interferon regulated genes in PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) of lupus patients is well established and is linked to the disease activity and the production of anti-dsDNA antibodies (18, 22, 23). Of note, both IFN-γ and IFN-β are known to be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms (24, 25), suggesting that epigenetic dysregulation of interferon genes is a plausible functional consequence of MECP2 polymorphism in lupus patients.

In a mouse model with an inducible ERK signaling defect resulting in reduced DNA methyltransferase 1 expression and abnormal expression of methylation sensitive genes, differential expression of interferon-regulated genes has also been reported (26). Further, stimulated T cells from female mice with a truncated form of MECP2 (Mecp2308/308) demonstrate significant overexpression of IFN-γ compared to wild-type mice (Sawalha et al. Unpublished observation).

We used an algorithm called IRIDESCENT (27, 28) to search the Medline database for relationships in the literature with the list of the differentially expressed genes as a result of MECP2 haplotypes. Several interesting significant relationships were identified with epigenetic-related mechanisms (Table 5). For example, among the upregulated genes, TMS1 (Target of Methylation-induced Silencing 1, (PYCARD, ASC) is a pro-apoptotic gene that is methylation sensitive and is epigenetically silenced in some cancers (29) and was recently found to affect the innate inflammatory response (30). Our data here suggests it is also sensitive to MECP2, either directly or indirectly. Vimentin and p18 (CDKN2C), genes found to be hypermethylated in some cancers (31, 32) were also upregulated. The expression of ITGAL (CD11a), an integrin molecule, is known to be regulated by DNA methylation (33). ITGAL is hypomethylated and overexpressed in lupus T cells, and its overexpression is associated with T cell autoreactivity in lupus patients (2, 34).

Among the down-regulated genes, there was the proto-oncogene MYC (c-Myc), which is known to affect DNA methylation and histone modifications (35, 36) and has been implicated in autoimmunity and SLE before (37, 38). SMARCA2 is a member of the chromatin remodeling family (SWI/SNF) of genes that regulate transcription by altering chromatin structure, and was recently reported as upregulated in the immunodeficiency syndrome ICF that is known to result from a mutation in the DNA methylating enzyme DNMT3B (39). PEG10 (Paternally Expressed Gene 10), an imprinted gene (40), was also downregulated.

We find a strong relationship in the literature between the differentially expressed genes, as the consequence of MECP2 haplotype carried, and epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation and histone modification. This further argues for a role of the identified MECP2 haplotypes in epigenetic dysregulation and supports the fact that the differentially expressed genes reflect target genes for MECP2 that are altered as a result of the lupus-associated MECP2 polymorphism. Of interest, this literature search identified a set of our differentially expressed genes and CREB1. CREB1 is a known transcription factor that has recently been identified as a key player in MECP2-induced transcriptional activation (10). Further, we identify a relationship in the literature with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is the first mammalian neuronal target gene for MECP2 identified and is thought to play a pathogenic role in patients with Rett Syndrome-associated MECP2 mutations (41).

In conclusion, our data replicate and further confirm the genetic association of polymorphism within the MECP2 gene and lupus. We identify a number of target genes that are dysregulated in B cells from lupus patients with the MECP2 lupus-risk haplotype. Importantly, MECP2 risk haplotype is associated with increased expression of a number of interferon-regulated genes and may play a role in the interferon signature observed in lupus patients. Further, the list of MECP2 target genes identified in lupus patients’ B cells can potentially uncover various aspects in the pathogenesis of the disease and help provide new therapeutic targets for lupus.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by NIH Grant Number P20-RR015577 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH Grant Number R03AI076729 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, funding from the Arthritis National Research Foundation and the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine (AHS), and NIH Grants Number AR42460, AI024717, AI31584, AR62277, AR048940, AR0490084, Kirkland Scholar award, Alliance for Lupus Research, and US Department of Veterans Affairs (JBH).

We are thankful to Dr. Peter Gregersen for providing DNA control samples for our study, and the Lupus Family Registry and Repository at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation for recruiting lupus patients and clinical materials used in this study. The microarray core facility receives funding support from the following NIH grants: P20RR016478, P20RR020143, P20RR15577, and U19AI062629; and from the following OCAST awards: AR061-015 and AR081-006. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Sawalha AH, Harley JB. Antinuclear autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(5):534–40. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000135452.62800.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson BC, Strahler JR, Pivirotto TS, Quddus J, Bayliss GE, Gross LA, et al. Phenotypic and functional similarities between 5-azacytidine-treated T cells and a T cell subset in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(6):647–62. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawalha AH, Richardson BC. DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Pharmacogenomics. 2005;3:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelik G, Fang JY, Wu A, Sawalha AH, Richardson B. Impaired T cell protein kinase C delta activation decreases ERK pathway signaling in idiopathic and hydralazine-induced lupus. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5553–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oelke K, Lu Q, Richardson D, Wu A, Deng C, Hanash S, et al. Overexpression of CD70 and overstimulation of IgG synthesis by lupus T cells and T cells treated with DNA methylation inhibitors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1850–60. doi: 10.1002/art.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, Johnson KJ, Richardson BC. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. Cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154(6):3025–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawalha AH, Jeffries M. Defective DNA methylation and CD70 overexpression in CD4+ T cells in MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(5):1407–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawalha AH, Webb R, Han S, Kelly JA, Kaufman KM, Kimberly RP, et al. Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3):e1727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, et al. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):187–91. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320(5880):1224–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dozmorov I, Centola M. An associative analysis of gene expression array data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):204–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wren JD, Garner HR. Shared relationship analysis: ranking set cohesion and commonalities within a literature-derived relationship network. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(2):191–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Gelder RN, von Zastrow ME, Yool A, Dement WC, Barchas JD, Eberwine JH. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(5):1663–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mnatzakanian GN, Lohi H, Munteanu I, Alfred SE, Yamada T, MacLeod PJ, et al. A previously unidentified MECP2 open reading frame defines a new protein isoform relevant to Rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(4):339–41. doi: 10.1038/ng1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kriaucionis S, Bird A. The major form of MeCP2 has a novel N-terminus generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1818–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett L, Palucka AK, Arce E, Cantrell V, Borvak J, Banchereau J, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):711–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, et al. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393(6683):386–9. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, Ray D, Yousif N, Richardson B. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in T cells from women with lupus. J Immunol. 2007;179(9):6352–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan FK, Zhou X, Mayes MD, Gourh P, Guo X, Marcum C, et al. Signatures of differentially regulated interferon gene expression and vasculotrophism in the peripheral blood cells of systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(6):694–702. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Peterson MG, Crow MK. Activation of the interferon-alpha pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1491–503. doi: 10.1002/art.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawalha AH. Epigenetics and T-cell immunity. Autoimmunity. 2008;41(4):245–52. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agalioti T, Lomvardas S, Parekh B, Yie J, Maniatis T, Thanos D. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-beta promoter. Cell. 2000;103(4):667–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawalha AH, Jeffries M, Webb R, Lu Q, Gorelik G, Ray D, et al. Defective T-cell ERK signaling induces interferon-regulated gene expression and overexpression of methylation-sensitive genes similar to lupus patients. Genes Immun. 2008;9(4):368–78. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wren JD. Extending the mutual information measure to rank inferred literature relationships. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wren JD, Bekeredjian R, Stewart JA, Shohet RV, Garner HR. Knowledge discovery by automated identification and ranking of implicit relationships. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):389–98. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons MJ, Vertino PM. Dual role of TMS1/ASC in death receptor signaling. Oncogene. 2006;25(52):6948–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, et al. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452(7183):103–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen WD, Han ZJ, Skoletsky J, Olson J, Sah J, Myeroff L, et al. Detection in fecal DNA of colon cancer-specific methylation of the nonexpressed vimentin gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(15):1124–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daa T, Kashima K, Kondo Y, Yada N, Suzuki M, Yokoyama S. Aberrant methylation in promoter regions of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor genes in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland. Apmis. 2008;116(1):21–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Q, Ray D, Gutsch D, Richardson B. Effect of DNA methylation and chromatin structure on ITGAL expression. Blood. 2002;99(12):4503–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Q, Kaplan M, Ray D, Ray D, Zacharek S, Gutsch D, et al. Demethylation of ITGAL (CD11a) regulatory sequences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(5):1282–91. doi: 10.1002/art.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benanti JA, Wang ML, Myers HE, Robinson KL, Grandori C, Galloway DA. Epigenetic down-regulation of ARF expression is a selection step in immortalization of human fibroblasts by c-Myc. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(11):1181–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu CH, van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Fan AC, Bachireddy P, Felsher DW. Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(32):13028–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701953104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boumpas DT, Tsokos GC, Mann DL, Eleftheriades EG, Harris CC, Mark GE. Increased proto-oncogene expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(6):755–60. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feghali CA, Boulware DW, Ferriss JA, Levy LS. Expression of c-myc, c-myb, and c-sis in fibroblasts from affected and unaffected skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity. 1993;16(3):167–71. doi: 10.3109/08916939308993324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrlich M, Sanchez C, Shao C, Nishiyama R, Kehrl J, Kuick R, et al. ICF, an immunodeficiency syndrome: DNA methyltransferase 3B involvement, chromosome anomalies, and gene dysregulation. Autoimmunity. 2008;41(4):253–71. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monk D, Wagschal A, Arnaud P, Sima-Muller P, Parker-Katiraee L, Bourc’his D, et al. Comparative analysis of human chromosome 7q21 and mouse proximal chromosome 6 reveals a placental-specific imprinted gene, TFPI2/Tfpi2, which requires EHMT2 and EED for allelic-silencing. Genome Res. 2008 doi: 10.1101/gr.077115.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun YE, Wu H. The ups and downs of BDNF in Rett syndrome. Neuron. 2006;49(3):321–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]