Abstract

Results from a series of psychophysical experiments show that interocular suppression produced by continuous flash suppression (CFS) differentially affects visual features of a target viewed by the other eye. When CFS stimuli are defined by luminance contrast, target color can be reliably identified but percent-correct discrimination of target orientation is near chance. When the colored target is moving, color identification deteriorates with motion speed but direction of motion discrimination improves with target speed. Color’s immunity to suppression is also weakened when interocular suppression is induced by equiluminant CFS stimuli that presumably stimulate the chromatic pathway. These results are discussed in terms of functional segregation of achromatic and chromatic processing in the visual system.

Color has a beguiling, promiscuous quality, in that it tends to show up in places where it does not belong. For example, color can spread beyond its figural boundaries into neighboring regions of the visual field, imparting a vivid sense of color where none actually exists. Compelling examples of color’s propensity to spread include neon color spreading (Bressan, Spillmann, Mingolla, & Watanabe, 1989) and the watercolor effect (Pinna, Brelstaff, & Spillmann, 2001). The color of a given object can also be erroneously assigned to other objects in the visual field, causing those objects to appear a color they are not. Examples include illusory binding in visual search (Treisman & Gelade, 1980), illusory binding during binocular rivalry (Creed, 1935; Holmes, Hancock, & Andrews, 2006), and the (mis)assignment of the color of foveally viewed moving objects to other objects moving in the peripheral visual field (Wu, Kanai, & Shimojo, 2004). These and other, related visual phenomena often are taken as evidence for distributed processing of form, motion, and color within the brain, with the neural signals within those distributed brain areas being imperfectly combined so that color can become unbound from the objects whose surfaces are generating those color signals.

We have discovered another set of conditions under which color becomes conspicuously unbound from form and motion, this one associated with a particularly potent form of interocular suppression called continuous flash suppression (CFS). First described by Tsuchiya and Koch (2005), CFS is produced by exposing one eye to a picture of an object, such as a face, while at the same time exposing the other eye to a rapidly, repetitively changing series of images, such as a montage of rectangles resembling a Mondrian pattern. Under these viewing conditions, the ordinarily visible, static picture can disappear from visual awareness for many seconds at a time. This loss of perceptual awareness is accompanied by a pronounced loss of visual sensitivity in the eye viewing the picture (Tsuchiya, Koch, Gilroy, & Blake, 2006). While constructing CFS displays for use in experiments on color-graphemic synesthesia, we were startled to discover that the color of an object, suppressed from awareness during CFS, could nonetheless be experienced as a diffuse, somewhat faint cloud appearing transparently on the grayscale rectangles forming the Mondrian patterns. This impression of color did not seem to be a surface property of the Mondrian itself but, instead, to be a transparent overlay with no defined shape. To reiterate, the shape of the colored object was itself completely suppressed from awareness. We describe this unbound color phenomenon in detail here and discuss its relevance for isolating and measuring properties of neural mechanisms involved in chromatic and achromatic vision.

METHOD

Participants

Five observers participated in the first two experiments and 4 observers participated in the motion-detection experiment. Observers (M.K., S.H., K.M., and D.B.) other than the authors (S.W.H. and R.B.) were naive about the purpose of the experiments. Each observer had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and had prior experience in psychophysical experiments involving interocular suppression.

Apparatus

All stimuli were generated using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) in conjunction with the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997) and were presented on an accurately calibrated Mitsubishi color display (Diamond Pro 2020u). Spectral power distributions of the red (R), green (G), and blue (B) phosphors were measured using a spectroradiometer (Ocean Optics, Model OOIBase 32). The relative light level of each gun at every digital value (256; 28 levels) was measured with a Minolta colorimeter (Model CA-100). The left and right halves of the display were viewed separately by the two eyes through a stereoscope; the mirrors were carefully adjusted for each observer to promote stable binocular alignment. The mirrors themselves were aluminum coated on their front surface (Opto-Sigma Model 033-0290). The observer’s head was stabilized by a chin- and headrest placed immediately in front of the stereoscope. The effective viewing distance was 95 cm. All experiments were performed in a dark room so that the only light source was from the stimulus display.

Stimuli and Procedure

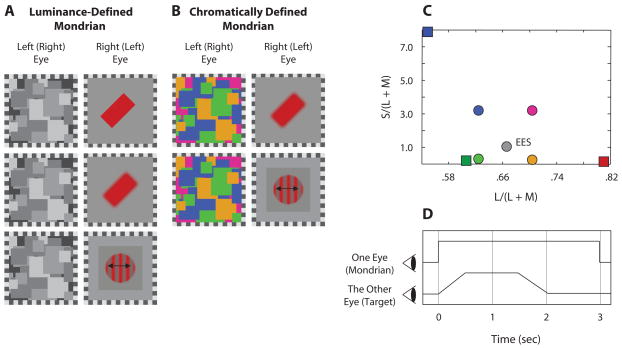

On each trial, one eye viewed the CFS stimuli and the other eye viewed a target bar or a grating. The Mondrian patterns used as CFS stimuli were composed of squares with random size (within limits) and location within a 4°-square aperture. For achromatic Mondrians (Figure 1A), each square was metameric to equal energy spectrum (EES) “white” with one of four luminance values (0, 3, 9, and 12 cd/m2), which induce 100% luminance contrast, at a maximum, with mean luminance at 6 cd/m2. For chromatic Mondrians (Figure 1B), luminance was fixed at 6 cd/m2 and chromaticity was chosen from four values [Chromaticity 1, L/(L+M) = 0.707, S/(L+M) = 3.3; Chromaticity 2, L/(L+M) = 0.707, S/(L+M) = 0.3; Chromaticity 3, L/(L+M) = 0.627, S/(L+M) = 3.3; Chromaticity 4, L/(L+M) = 0.627, S/(L+M) = 0.3; shown in cone-excitation color space (MacLeod & Boynton, 1979; the present Figure 1C)]. Calculation of chromaticity values was based on Smith–Pokorny 2° cone fundamentals (Smith & Pokorny, 1975). An equiluminant level of each of the three CRT phosphors was measured for every observer using heterochromatic modulation photometry at 15 Hz (Pokorny, Smith, & Lutz, 1989).

Figure 1.

(A) Stimulus configuration with achromatic continuous flash suppression (CFS) stimuli composed of achromatic patches, each of which was one of four luminance values. In Experiments 1 and 2, the target presented to one eye was either a 1° × 2° bar with sharp edges (top) or a blurred bar (middle); for either type of bar, orientation and color varied over trials. In Experiment 3, the target was a 2 cyc/deg sine-wave grating that drifted leftward or rightward (bottom); this grating had both luminance and chromatic contrast. (B) Stimulus configuration with chromatic CFS stimuli composed of equiluminant chromatic patches, each of which was one of four different chromaticities (for purposes of illustration in this grayscale figure, patches are shown using luminance contrast). (C) Chromaticities of targets (squares) and chromaticities used for chromatic Mondrian patterns (circles) shown in cone-excitation space (MacLeod & Boynton, 1979). (D) Temporal profile of stimulus presentation.

In Experiments 1 and 2, the target was a 1° × 2° bar presented within a uniform 4° EES field with luminance at 6 cd/m2. In Experiment 1, this target bar had sharp edges (Figure 1A, top) and in Experiment 2 the bar was filtered with a Gaussian filter (σ = 0.15° visual angle). The orientation of the target bar was one of three values (horizontal and ±45° from vertical), and the color of the target bar was one of three chromaticities [Chromaticity 1 appearing reddish, L/(L+M) = 0.80, S/(L+M) = 0.12; Chromaticity 2 appearing greenish, L/(L+M) = 0.61, S/(L+M) = 0.17; Chromaticity 3 appearing bluish, L/(L+M) = 0.55, S/(L+M) = 8.5; Figure 1C squares]. Luminance of the target bar was fixed at 4 cd/m2. For the reaction time (RT) experiment, only two orientations (±45° from vertical) and two chromaticities (Target Chromaticities 1 and 3) were used. In Experiment 3, the target was a 2 cyc/deg, drifting, colored, vertical grating with Gaussian envelope. The contours of the grating appeared either “red” (Chromaticity Value 1) and gray or “green” (Chromaticity Value 2) and gray, and the luminance contrast of these gratings was 20%. The grating drifted either leftward or rightward at 2.5°, 5.0°, and 7.5°/sec.

In general, one session of the experiment was composed of either 180 trials (3 colors × 3 orientations × 2 eye positions × 10 repetitions) or 80 trials (2 colors × 2 orientations/directions of motion × 2 eye positions × 10 repetitions). Each trial consisted of the following sequence of events. Appearing first was a pair of checkerboard frames that outlined the two uniform gray fields within which the Mondrian patterns (one eye) and the target (other eye) would then be presented. The dynamic (20-Hz) Mondrian patterns appeared abruptly and remained on for 3 sec; at the same time the Mondrian appeared, the contrast of the bar (grating) ramped up to its maximum value over a 0.5-sec period, remained at this level for 1 sec, and then ramped down in contrast over a 0.5-sec period. Thus, after the target disappeared, the Mondrian patterns remained present for 1 sec longer while a uniform EES field was presented to the eye previously viewing the target (Figure 1D). This additional 1 sec of CFS stimulation ensured that observers could not base their orientation or color judgments on a lingering afterimage of the target bar, which was often briefly visible if both the CFS and the bar were extinguished at the same time (cf. Gilroy & Blake, 2005). The color and orientation of the target were randomized for every trial, and the eye receiving the target was also randomized. Observers indicated the color and orientation (or direction of motion) of the target by pressing preassigned buttons on a game pad after the stimulus presentation. In the RT experiment, trial duration was 8 sec, and observers pressed preassigned buttons as soon as they identified the color or the orientation of the target while stimuli were on. The target presentation was terminated abruptly, without ramping. As in the other experiments, 1 sec of dynamic Mondrian pattern presentation followed the removal of the target. Each session was repeated three times for each individual observer.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Color and Form Identification During CFS

The first experiment documented our phenomenological observations by measuring how reliably the orientation and the color of a monocularly viewed, rectangular bar could be identified when that bar was suppressed by a series of rapidly changing, achromatic Mondrian patterns presented to the other eye (Figure 1A, top).

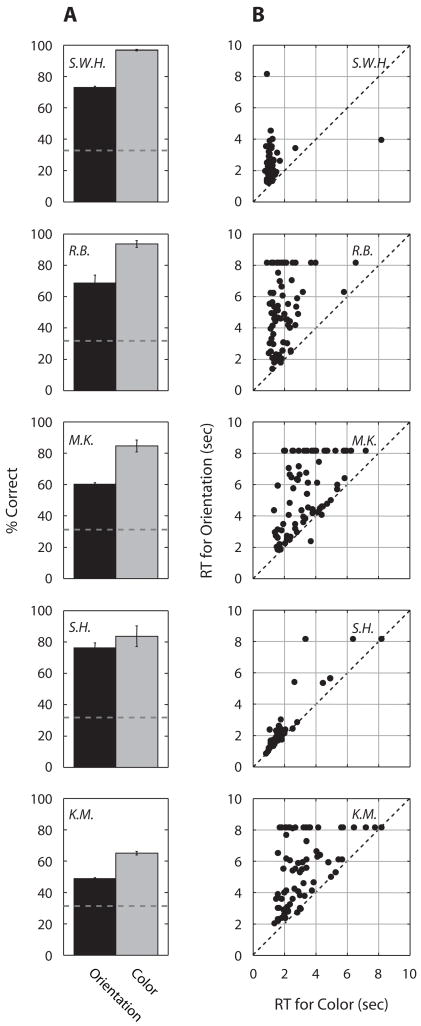

All of the observers were able to identify color with high accuracy, but their performance on the orientation task was consistently lower than that on the color task (Figure 2A). Observers commented that the impression of color emerged almost immediately and prior to any impression of the orientation of the bar, which, when it was identifiable, emerged at the very end of the brief presentation. This disparity in perception time between color and form led us to perform a modified version of this first experiment in which the target bar remained present for up to 8 sec. We used only two colors and two orientations in this modified version, so that the RT task would be easy enough that observers could respond without confusion using four buttons. On each trial, the observer responded as quickly as possible to indicate the color (one key for red, another for blue) and the orientation (one key for diagonal left, another for diagonal right) of the bar; observers based their order of judgments on the order in which the two stimulus qualities were evident on a given trial. A trial was terminated once both responses were made or after 8 sec had elapsed, in which case an RT of 8 sec was recorded for the stimulus quality (color and/or orientation) that remained unperceived.

Figure 2.

(A) Percent-correct identification of orientation (black bar) and color (gray bar) of the target bar with sharp edges. Dashed lines represent the chance level for both tasks (33%). Error bars represent ±1 SE. (B) Reaction time (RT) for identification of color (horizontal axis) and for identification of orientation (vertical axis). Each point specifies the pair of RT values for a given trial.

On nearly all the trials, the latency for identifying color was considerably shorter than the latency for identifying orientation (Figure 2B). Error rates for the color responses and the orientation responses were negligible, but there were a substantial number of trials on which orientation responses were not even made within the 8-sec period of stimulus presentation (i.e., the data points where orientation RTs are plotted as 8 sec). This pattern of results merely verifies what observers described anecdotally: Color nearly always emerged into dominance well before the orientation of the bar was perceived.

One could argue that color is more easily identified than shape because a color decision requires a relatively small number of colored pixels breaking through suppression, whereas form identification requires dominance of a spatially structured patch of pixels. Perceptually, however, that is not what one experiences: Color does not break suppression and replace portions of the Mondrian but, instead, appears as a formless cloud of color superimposed on the still visible achromatic rectangles of the Mondrian. The bar itself, when it does emerge into visibility, appears in place of the Mondrian, which itself temporarily succumbs to suppression.

Experiment 2: CFS Differentially Affects Color and Form Identification

The results from Experiment 1 reveal that CFS exerts a significantly different effect on identification of color and identification of form, with color often surviving interocular suppression while form is rendered invisible on a substantial percentage of trials. This pattern of results implies that rapidly flickering, achromatic Mondrian patterns have a relatively weak impact on neural mechanisms involved in color perception, enabling color to survive CFS. Neural events supporting identification of contour orientation, by comparison, seem more susceptible to CFS, although observers are able to identify a bar’s orientation on some trials.

To explore the boundary conditions for the effectiveness of CFS, we modified our stimuli in several ways. First, we wondered whether the sharp edges of the bar might be contributing to the residual visibility of that stimulus, since in other contexts stimuli containing high spatial frequencies disrupted interocular suppression more frequently than did stimuli containing low spatial frequencies only (Tsuchiya & Koch, 2005). To examine whether sharp edges were contributing to the bar’s residual visibility, we used a Gaussian filter to blur the bar’s edges while leaving its orientation clearly identifiable (Figure 1A, middle). Second, we felt it worthwhile to test the efficacy of Mondrian patterns the components of which were chromatic, equiluminant figures, to learn whether the chromatic content of the stimulus inducing interocular suppression affects color perception of the stimulus undergoing suppression. So in this second experiment we tested color and orientation identification using either achromatic Mondrians like those used before or equiluminant chromatic Mondrians (Figure 1B, top). The sequence of events on each trial was identical to that shown in Figure 1D, and again, as in our initial experiment, we used three equally likely orientations and three equally likely colors randomly combined to yield a total of nine different target bars.

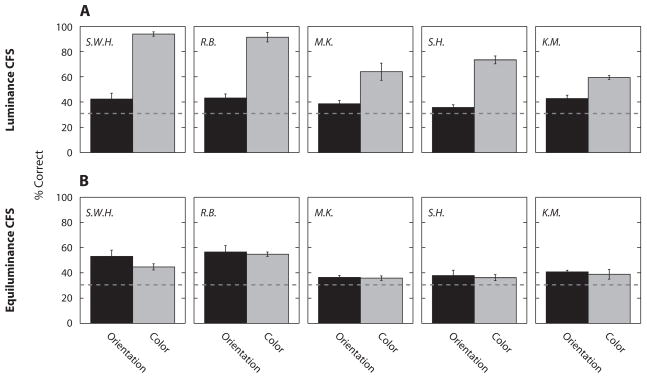

With achromatic Mondrian patterns, observers’ ability to identify color was significantly above chance [S.W.H., t(2) = 35.88, p < .001; R.B., t(2) = 15.56, p < .01; M.K., t(2) = 4.59, p < .05; S.H., t(2) = 13.15, p < .01; K.M., t(2) = 17.99, p < .01], again revealing that chromatic information is relatively immune to CFS with achromatic Mondrians (Figure 3A). Moreover, the achromatic Mondrian now more effectively suppressed form information, as evidenced by the near chance performance (dashed line in Figure 3) on the forced-choice orientation-identification task; for 3 out of 5 observers, performance was not significantly different from chance, and for the other 2, performance was significantly above chance, but t values were small [S.W.H., t(2) = 1.99, p > .05; R.B., t(2) = 3.34, p < .05; M.K., t(2) = 2.21, p > .05; S.H., t(2) = 1.28, p > .05; K.M., t(2) = 3.72, p < .05]. Thus, when the target bar had blurred edges, correct identification for orientation was substantially worse than performance with sharp-edged bars (Figure 2A), implying that high spatial frequency components are less susceptible to suppression exerted by an achromatic Mondrian.

Figure 3.

(A) Identification of orientation (black bar) and color (gray bar) of the blurred target bar with CFS by luminance-defined Mondrian patterns. (B) The same as (A), but with CFS by chromatically defined Mondrian patterns. Dashed lines represent the chance level for both tasks (33%). Error bars represent ±1 SE.

Turning next to results with the equiluminant chromatic Mondrians (Figure 3B), we note that color identification plummeted relative to identification performance measured with achromatic Mondrians [planned contrast analysis: S.W.H., F(1,8) = 106.43, p < .001; R.B., F(1,8) = 51.38, p < .001; M.K., F(1,8) = 27.20, p < .001; S.H., F(1,8) = 74.51, p < .001; K.M., F(1,8) = 32.94, p < .001], whereas orientation identification performance remained the same for 4 observers and improved for the 5th observer [planned contrast analysis: S.W.H., F(1,8) = 4.62, p > .05; R.B., F(1,8) = 6.69, p < .05; M.K., F(1,8) = 0.17, p > .05; S.H., F(1,8) = 0.27, p > .05; K.M., F(1,8) = 0.27, p > .05]. We also tested observers on monocular control trials in which the colored bar was physically superimposed on the chromatic Mondrian, to ascertain whether the drop in color identification was attributable to masking. In this control condition, the target bar was embedded into the Mondrian patterns by pixel-by-pixel replacement. Color identification on these trials was essentially perfect, verifying that the inability to identify color in the interocular condition was not attributable to the color becoming camouflaged by the colors of the chromatic Mondrian but, instead, was attributable to interocular suppression. Compared with achromatic Mondrians, chromatic Mondrians more effectively suppress chromatic signals from the other eye. We made no attempt to equate these two types of Mondrians in terms of effective contrast, but it is inevitably true that the achromatic Mondrians produced higher cone contrast than did the chromatic Mondrians. Nonetheless, color is less affected by CFS created by achromatic Mondrians, implying that postreceptoral mechanisms are mediating these suppression effects.

So, our results imply that chromatic and achromatic CFS stimuli exert differential effects on visual processing as reflected in interocular suppression.

Experiment 3: Color and Motion

Our final experiment examined the impact of suppression produced by chromatic and by achromatic Mondrians on perception of a drifting, colored grating. It is generally recognized that neurons specialized for the analysis of motion (e.g., neurons within visual area MT) are less responsive when activated by purely chromatic stimuli, compared with activation produced by luminance-defined stimuli (Gegenfurtner et al., 1994). With this in mind, suppose that one eye views a luminance-defined, colored grating drifting in one of two directions and the other eye views either a dynamic, luminance-defined achromatic Mondrian (which should strongly activate motion-sensitive neurons) or a dynamic, equiluminant chromatic Mondrian (which should only weakly activate motion-sensitive neurons). The relatively weak color sensitivity of motion-selective neurons leads to the prediction that perception of direction of motion should be more severely affected by the achromatic Mondrian. On the other hand, judgments of the color of the moving grating should be more seriously affected by the chromatic Mondrian.

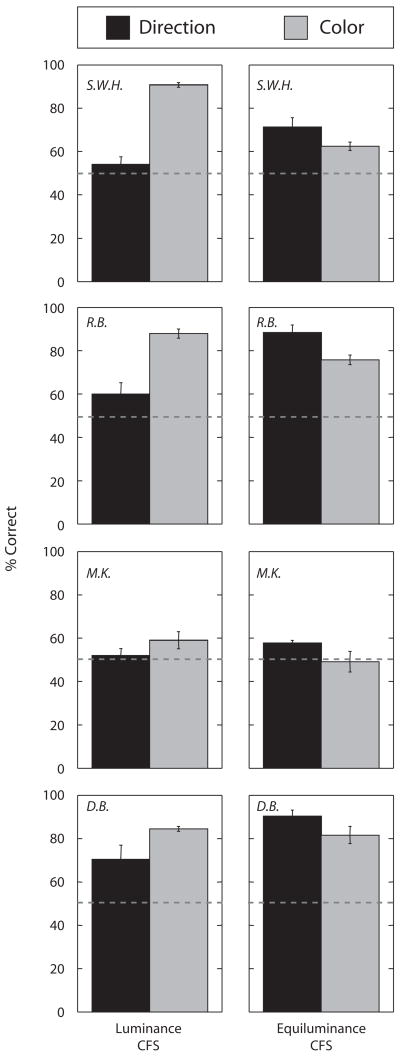

We measured observers’ ability to discriminate the direction of motion of a vertical sine-wave grating whose contours were defined by luminance and chromatic contrast (i.e., this is not an equiluminant grating); the grating drifted either leftward or rightward at 5 Hz (2.5 deg/sec). This drifting, colored grating was viewed by one eye while, at the same time, the other eye viewed either achromatic (Figure 1A, bottom) or chromatic (Figure 1B, bottom) Mondrians. The color of the grating (red vs. green) and its direction of motion (left vs. right) were varied randomly and independently of one another over trials.

The two different Mondrian patterns, chromatic and achromatic, had opposite effects on these two concurrently performed tasks, color identification and motion discrimination. Motion-direction judgments were more accurate when the grating was suppressed by the chromatic, equiluminant Mondrian than by the achromatic Mondrian (Figure 4, black bars); the statistical significance of these differences was confirmed by planned contrast analyses [S.W.H., F(1,8) = 16.32, p < .01; R.B., F(1,8) = 32.79, p < .001; M.K., F(1,8) = 25.79, p < .001; D.B., F(1,8) = 11.88, p < .01]. Color identification judgments, however, were as accurate or even more accurate when the grating was suppressed by the achromatic Mondrian (Figure 4, gray bars); for 2 observers, the differences between these two conditions were statistically significant [S.W.H., F(1,8) = 44.89, p < .001; R.B., F(1,8) = 5.96, p < .05] and for 2 others the two conditions were statistically equivalent [M.K., F(1,8) = 0.36, p > .05; D.B., F(1,8) = 0.25, p > .05].

Figure 4.

Identification of direction of motion (black bar) and color (gray bar) of the target grating with CFS by luminance-defined Mondrian patterns (left column) and with CFS by chromatically defined Mondrian patterns (right column). Dashed lines represent the chance level for both tasks (50%). Error bars represent ±1 SE.

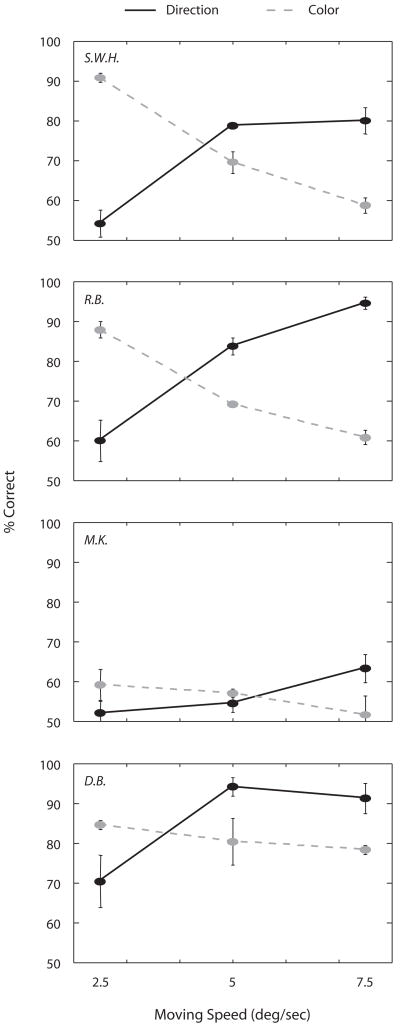

In a final experiment, we tested color identification and direction discrimination using the same drifting grating whose speed now varied over trials from 2.5° to 7.5°/sec. This grating was viewed by one eye while the other eye viewed an achromatic CFS stimulus only. Our reasoning was as follows. It is well established that motion sensitivity increases with temporal frequency up to around 10 Hz for luminance-defined gratings (Gegenfurtner & Hawken, 1996), whereas color sensitivity decreases with increasing temporal frequency (Shady, MacLeod, & Fisher, 2004). Thus, varying the speed of motion of a drifting, colored grating should produce complementary variations in the effective strength of the signals produced by that grating in motion-sensitive and color-sensitive mechanisms. And to the extent that the strength of neural response determines the probability of the grating’s overcoming the effect of interocular suppression from a CFS stimulus, we can make the following prediction: When paired dichoptically with an achromatic CFS stimulus, identification of motion direction should improve with temporal frequency, while, at the same time, identification of color should deteriorate.

Consistent with this prediction, correct identification for color decreased and correct identification for direction of motion increased with increasing the speed of the moving grating (Figure 5). For 3 of the 4 observers, the perceptual experience at the highest speed motion was particularly remarkable: These individuals often clearly saw the contours of the grating moving in a given direction, yet those contours appeared completely achromatic, as if the color had been bleached from them. For a 4th observer (M.K.), both judgments were quite difficult at all drift speeds, with only the hint of dissociation at the highest speed.

Figure 5.

Identification of direction of motion (solid line) and color (dashed line) as a function of motion speed. Error bars represent ±1 SE.

DISCUSSION

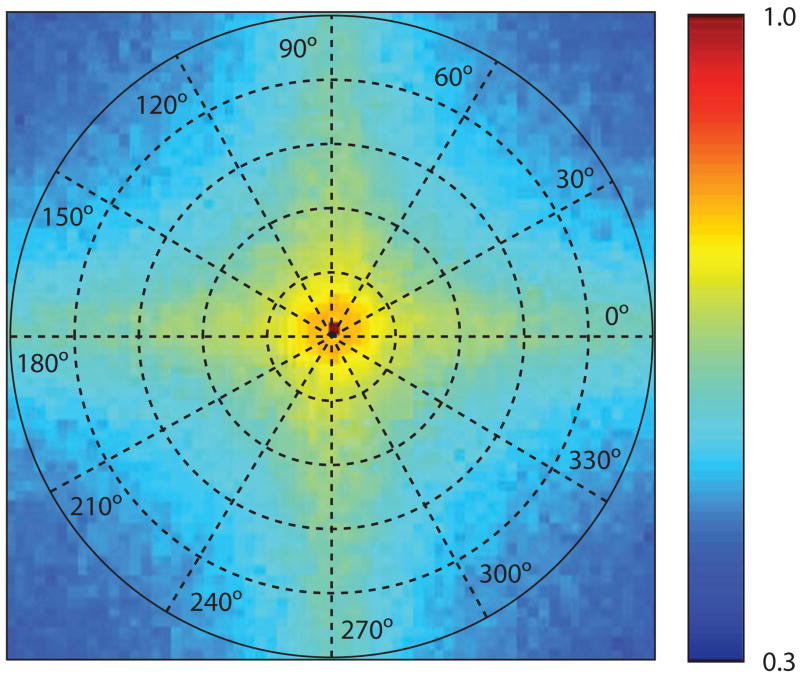

CFS provides a remarkably effective means for erasing an ordinarily visible stimulus from perceptual awareness for many seconds at a time (Tsuchiya & Koch, 2005). In recent years, this potent technique has been used fruitfully in psychophysical (Jiang, Costello, & He, 2007; Jiang & He, 2006; Yang, Zald, & Blake, 2007) and brain imaging studies (Fang & He, 2005) aimed at identifying neural processes involved in face perception, object recognition, and attention. The effectiveness of CFS is no doubt related to the complex Fourier spectrum of the constituent Mondrian patterns comprising the CFS (Figure 6) as well as to the rapid, successive presentation of different patterns whose spatial dissimilarity minimizes visual adaptation and whose dynamics create a steady train of transients. For that matter, there is probably nothing magic about successively presented Mondrian patterns—any series of natural scene images presented in rapid succession would surely also constitute a potent CFS sequence so long as those images were complex and the constituent features varied in location from image to image in a manner that minimized local adaptation (e.g., Pasley, Mayes, & Schultz, 2004).1

Figure 6.

Normalized amplitude spectrum derived from Fourier analysis of a sequence of achromatic Mondrian patterns used for CFS (n = 20). The scale shown to the right represents relative energy (normalized to the DC value) at different spatial frequencies (specified by distance from the origin) and orientations (specified by polar angle). Comparing this average spectrum with that for the spectrum of each of the 20 constituent Mondrian patterns reveals that these spectra are highly similar: The standard deviation of pixel values at each location in the spectrum images is no greater than 7% of the mean. Notice that the spectrum is anisotropic at higher spatial frequencies only, where energy is concentrated at horizontal and vertical orientations. Not captured in this plot is the dynamic nature of the Mondrians used to generate CFS. That property is captured in the successive phase spectra associated with successive images (each phase spectrum contains values spanning the range ± π). The standard deviations of phase values in those spectra average 29% of the full range of possible variation.

In view of CFS’s potency, it is remarkable that color frequently survives interocular suppression caused by dynamic, achromatic Mondrians. Specifically, perception of the shape of a colored object viewed by one eye can be substantially impaired during CFS, but that object’s color remains visible. This residual color does not necessarily appear as part of the surface of the achromatic rectangles comprising the CFS stimulus viewed by the other eye but, instead, seems to form a colored haze floating on top of those rectangles. In the original study introducing CFS, there is some hint that color is less affected by CFS produced by achromatic Mondrians than is form: Tsuchiya and Koch (2005) mentioned that colored Gabor patches remained completely suppressed for relatively short periods of time compared with grayscale Gabor patches. Moreover, in the binocular rivalry literature, one encounters results that presage the immunity of color to interocular suppression from CFS. Thus, for example, several investigators have noted that the shape and color appearance of a rival target can become uncoupled during binocular rivalry, so that an observer viewing rival stimuli occasionally experiences the shape imaged in one eye together with the color imaged in the other eye (Holmes et al., 2006; Lange-Malecki, Creutzfeldt, & Hinse, 1985) or experiences a fusion of the two colors but monocular dominance of one form or the other (Creed, 1935; Holmes et al., 2006; Stirling, 1901). It is also possible for two different colors, one presented to each eye, to be perceived simultaneously while two different forms are alternating in dominance (Hong & Shevell, 2006). In a similar vein, color and motion information can become dissociated during binocular rivalry (Carny, Shadlen, & Switkes, 1987). All things considered, it may be reasonable to consider CFS as a type of binocular rivalry, albeit a type that strongly biases interocular competition in favor of one stimulus, owing to its spatiotemporal qualities.

The differential susceptibility of form, color, and motion to interocular suppression induced by an achromatic CFS stimulus makes some sense in terms of what we know about neural processing of those stimulus dimensions. Within the neurophysiological literature, there has been debate about the extent to which orientation-selective cells in primary visual cortex also respond selectively to color (for a review, see Gegenfurtner, 2003). But one emerging view is that primary visual cortex contains what Engel (2007) calls dual representations of color—one integrated with form information and the other that is independent of form. It also seems clear that a significant fraction of color-selective neurons in primary visual cortex exhibit binocular interactions that have nothing to do with specification of 3-D spatial form but, instead, are purely representing surface color (Peirce, Solomon, Forte, & Lennie, 2008). In addition, the consensus seems to be that color and motion information are at least partially differentiated in terms of mechanisms selective for processing those two visual qualities (Gegenfurtner & Hawken, 1996). This, too, could relate to the differential effect of CFS on color perception and motion discrimination that we have found.

Is it possible that CFS exerts its effects at very early stages in the visual hierarchy, where chromatic and achromatic processing are segregated within the parvocellular (PC), magnocellular (MC), and koniocellular (KC) pathways? Decades of research show that neurons that make up these pathways have markedly different chromatic properties, and they respond to different ranges of spatial and temporal frequencies. Moreover, PC neurons and MC neurons respond quite differently to variations in luminance and chromatic contrast (Lee, Pokorny, Smith, Martin, & Valberg, 1990). In particular, PC neurons respond weakly to luminance contrast but show robust responses to chromatic contrast; MC neurons, in comparison, respond vigorously to luminance contrast and weakly, if at all, to chromatic contrast. (KC neurons seem to possess more heterogeneous response properties, behaving like PC neurons in some ways and MC neurons in others; Kaplan, 2003.) On the basis of these response properties, one could imagine that an achromatic Mondrian produces stronger activation within MC neurons and a chromatic Mondrian produces stronger activation within PC neurons. Could MC and PC neurons account for the differential effect of these two types of Mondrians on the survival of color perception during CFS?

Such an explanation would be tantamount to assuming that the neural events underlying CFS transpire at very early stages of processing, prior to cortical areas where signals carried in these different pathways converge. It is known that PC, KC, and MC neurons remain segregated within the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) and that they project to different cellular layers within the primary visual cortex (Callaway, 1998). But is it reasonable to assume that neural events underlying interocular suppression from CFS arise at such early stages in the visual hierarchy? This possibility is not altogether far-fetched. It is well known that (1) adjacent layers of the LGN within a given brain hemisphere are innervated by contralateral and ipsilateral eyes, respectively; (2) these adjacent layers are also interconnected by inhibitory neurons; and (3) PC and MC neurons are found in separate layers of the LGN. Because these layers are all retinotopically organized, the LGN possesses a neural architecture well suited for promoting pathway-specific interocular inhibition. In fact, there are human brain imaging studies showing that alternations in dominance and suppression during binocular rivalry are accompanied by modulation in BOLD signals arising in LGN (Haynes, Deichmann, & Rees, 2005; Wunderlich, Schneider, & Kastner, 2005). We do not know whether those BOLD signal modulations are intrinsic to the LGN or arise from feedback from visual cortex, but in any event these brain imaging results suggest that at least some of the neural concomitants of interocular suppression can be found within the LGN. It remains for future work to determine whether the strength of those modulations in BOLD signal is dependent on the chromatic and achromatic properties of the stimuli inducing interocular suppression.

Regardless of the specifics of the underlying neural mechanisms, the present results suggest that different CFS configurations may have a different impact on visual processing of different aspects of the visual scene. Color’s ability to survive CFS is seriously compromised when the CFS viewed by the other eye is composed of chromatic rectangles. At the same time, the form information associated with that colored object is less affected, and when that object is moving it is actually less susceptible to interocular suppression from the chromatic CFS. Considered together, this pattern of results suggests the possibility that interocular suppression generated by a CFS stimulus can be tailored for form, for color, or for motion by appropriate selection of the chromatic and spatial frequency properties of the CFS stimulus and the stimulus presented to the other eye.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants EY13358 and EY016752.

Footnotes

In an unpublished study carried out in collaboration with Uri Hasson and David Heeger, our laboratory has established that excerpts from animations containing continuous action constitute potent stimuli for generating prolonged periods of interocular suppression.

References

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan P, Spillmann L, Mingolla E, Watanabe T. Neon color spreading: A review. Perception. 1989;26:1353–1366. doi: 10.1068/p261353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway EM. Local circuits in primary visual cortex of the macaque monkey. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1998;21:47–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carny T, Shadlen M, Switkes E. Parallel processing of motion and colour information. Nature. 1987;328:647–649. doi: 10.1038/328647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed RS. Observations on binocular fusion and rivalry. Journal of Physiology. 1935;84:381–392. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1935.sp003288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA. Computational cognitive neuroscience of the visual system. Current Direction in Psychological Science. 2007;17:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, He S. Cortical response to invisible objects in the human dorsal and ventral pathways. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1380–1385. doi: 10.1038/nn1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR. Cortical mechanisms of colour vision. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR, Hawken MJ. Interaction of motion and color in the visual pathways. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:394–401. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR, Kiper DC, Beusmans J, Carandini M, Zaidi Q, Movshon JA. Chromatic properties of neurons in macaque MT. Visual Neuroscience. 1994;11:455–466. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000239x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy LA, Blake R. The interaction between binocular rivalry and negative afterimages. Current Biology. 2005;15:1740–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JD, Deichmann R, Rees G. Eye-specific effects of binocular rivalry in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nature. 2005;438:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature04169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DJ, Hancock S, Andrews TJ. Independent binocular integration for form and color. Vision Research. 2006;46:665–677. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SW, Shevell SK. Resolution of binocular rivalry: Perceptual misbinding of color. Visual Neuroscience. 2006;23:561–566. doi: 10.1017/S0952523806233145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Costello P, He S. Processing of invisible stimuli: Advantage of upright faces and recognizable words in overcoming interocular suppression. Psychological Science. 2007;18:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, He S. Cortical responses to invisible faces: Dissociating subsystems for facial-information processing. Current Biology. 2006;16:2023–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E. The M, P, and K pathways of the primate visual system. In: Chalupa L, Werner J, editors. The visual neurosciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Malecki B, Creutzfeldt OD, Hinse P. Haploscopic colour mixtures with and without contours in subjects with normal and disturbed binocular vision. Perception. 1985;14:587–600. doi: 10.1068/p140587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BB, Pokorny J, Smith VC, Martin PR, Valberg A. Luminance and chromatic modulation sensitivity of macaque ganglion cells and human observers. Journal of the Optical Society of America A. 1990;7:2223–2236. doi: 10.1364/josaa.7.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod DIA, Boynton RM. Chromaticity diagram showing cone excitation by stimuli of equal luminance. Journal of the Optical Society of America. 1979;69:1183–1186. doi: 10.1364/josa.69.001183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasley BN, Mayes LC, Schultz RT. Subcortical discrimination of unperceived objects during binocular rivalry. Neuron. 2004;42:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JW, Solomon SG, Forte JD, Lennie P. Cortical representation of color is binocular. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(3):1–10. doi: 10.1167/8.3.6. Art. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna B, Brelstaff G, Spillmann L. Surface color from boundaries: A new “watercolor” illusion. Vision Research. 2001;41:2669–2676. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny J, Smith VC, Lutz M. Heterochromatic modulation photometry. Journal of the Optical Society of America A. 1989;6:1618–1623. doi: 10.1364/josaa.6.001618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shady S, MacLeod DIA, Fisher HS. Adaptation from invisible flicker. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:5170–5173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303452101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith VC, Pokorny J. Spectral sensitivity of the foveal cone photopigments between 400 and 500 nm. Vision Research. 1975;15:161–171. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(75)90203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling W. An experiment on binocular colour vision with half-penny postage-stamps. Journal of Physiology. 1901;27:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman AM, Gelade G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology. 1980;12:97–136. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya N, Koch C. Continuous flash suppression reduces negative afterimage. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1096–1101. doi: 10.1038/nn1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya N, Koch C, Gilroy LA, Blake R. Depth of interocular suppression associated with continuous flash suppression, flash suppression, and binocular rivalry. Journal of Vision. 2006;6:1068–1078. doi: 10.1167/6.10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Kanai R, Shimojo S. Steady-state misbinding of colour and motion. Nature. 2004;429:262. doi: 10.1038/429262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich K, Schneider K, Kastner S. Neural correlates of binocular rivalry in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1595–1602. doi: 10.1038/nn1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Zald DH, Blake R. Fearful expressions gain preferential access to awareness during continuous flash suppression. Emotion. 2007;7:882–886. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]