Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with chronic pulmonary diseases are at increased risk of hypoxemia when travelling by air. Screening guidelines, predictive equations based on ground level measurements and altitude simulation laboratory procedures have been recommended for determining risk but have not been rigorously evaluated and compared.

OBJECTIVES:

To determine the adequacy of screening recommendations that identify patients at risk of hypoxemia at altitude, to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of published predictive equations, and to analyze other possible predictors of the need for in-flight oxygen.

METHODS:

The charts of 27 consecutive eligible patients referred for hypoxia altitude simulation testing before flight were reviewed. Patients breathed a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.15 for 20 min. This patient population was compared with the screening recommendations made by six official bodies and compared the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) obtained during altitude simulation with the PaO2 predicted by 16 published predictive equations.

RESULTS:

Of the 27 subjects, 25% to 33% who were predicted to maintain adequate oxygenation in flight by the British Thoracic Society, Aerospace Medical Association or American Thoracic Society guidelines became hypoxemic during altitude simulation. The 16 predictive equations were markedly inaccurate in predicting the PaO2 measured during altitude simulation; only one had a positive predictive value of greater than 30%. Regression analysis identified PaO2 at ground level (r=0.50; P=0.009), diffusion capacity (r=0.56; P=0.05) and per cent forced expiratory volume in 1 s (r=0.57; P=0.009) as having predictive value for hypoxia at altitude.

CONCLUSIONS:

Current screening recommendations for determining which patients require formal assessment of oxygen during flight are inadequate. Predictive equations based on sea level variables provide poor estimates of PaO2 measured during altitude simulation.

Keywords: Altitude, COPD, Flight, Hypoxemia, Hypoxia altitude simulation test, Normobaric challenge, Recommendations

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les patients qui souffrent de maladie pulmonaire chronique sont exposés à un risque accru d’hypoxémie lorsqu’ils prennent l’avion. Des lignes directrices en matière de dépistage, fondées sur des équations prédictives calculées à partir de mesures au sol et d’épreuves de simulation d’altitude en laboratoire, ont été recommandées pour évaluer le risque, mais n’ont pas fait l’objet de vérifications ni de comparaisons rigoureuses.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer la justesse des recommandations pour le dépistage du risque d’hypoxémie chez ces patients, évaluer la spécificité et la sensibilité des équations prédictives publiées et analyser d’autres facteurs permettant de prédire la nécessité d’administrer de l’oxygène durant le vol.

MÉTHODE :

Les auteurs ont passé en revue les dossiers de 27 patients consécutifs admissibles, adressés pour épreuve de simulation d’hypoxémie en altitude avant une envolée. Les patients ont respiré une fraction d’oxygène inspiré de 0,15 pendant 20 minutes. Cette population de patients a servi de base de comparaison entre les recommandations de six instances officielles relativement au dépistage et a permis de comparer la pression partielle artérielle en oxygène (PaO2) obtenue durant la simulation d’altitude aux prédictions de PaO2 calculées au moyen de 16 équations prédictives publiées.

RÉSULTATS :

Parmi les 27 sujets, de 25 % à 33 % chez qui on avait prédit le maintien d’une oxygénation adéquate en vol selon les lignes directrices de la British Thoracic Society, de l’Aerospace Medical Association ou de l’American Thoracic Society ont développé une hypoxémie durant la simulation d’altitude. Les 16 équations prédictives se sont révélées très imprécises pour ce qui est de prévoir la PaO2 mesurée durant la simulation d’altitude. Une seule a présenté une valeur prédictive positive supérieure à 30 %. L’analyse de régression a permis d’identifier la PaO2 au sol (r = 0,50; P = 0,009), la capacité de diffusion (r = 0,56; P = 0,05) et le pourcentage du volume expiratoire maxime en une seconde (r = 0,57; P = 0,009) comme des éléments dotés d`une valeur prédictive pour ce qui est de prévoir l’hypoxémie en altitude.

CONCLUSION :

Les recommandations actuelles en matière de dépistage des patients susceptibles de nécessiter une évaluation formelle de leurs besoins en oxygène en vol sont inadéquates. Les équations prédictives établies à partir de variables mesurées au niveau de la mer donnent des estimations erronées de la PaO2 mesurée lors de la simulation d’altitude.

The growing prevalence of chronic pulmonary disease ensures that clinicians will increasingly be called on to evaluate their patients’ fitness to travel by air. Travel by modern airliner exposes patients to the reduced ambient oxygen tensions equivalent to those experienced at 2438 m above sea level for several hours, which can cause significant hypoxemia in individuals with chronic lung disease.

In the physician’s office, determining the impact of high-altitude exposure involves two steps. The first step is to screen the large population of patients with chronic lung diseases for the likelihood of developing hypoxemia during flight, who, therefore, require more careful evaluation. The recommendations made by various official bodies are discrepant on whom to test. The British Thoracic Society (BTS), American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS), the Aerospace Medical Association (AMA) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have published recommendations for the evaluation of patients at risk (1–5). The BTS recommends a hypoxia altitude simulation test (HAST) for patients with a baseline saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) of between 92% and 95%, and an additional risk factor (1). Values outside of this range imply safety or the need for supplemental oxygen. The ATS/ERS guidelines and VA guidelines recommend a HAST for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with comorbidities, previous in-flight symptoms, recent exacerbation(s), hypoventilation on oxygen administration or borderline estimates from a regression equation (2,5). The AMA and CTS consider a partial pressure of arterial oxygen at ground level (PaO2gr) of less than 70 mmHg to be an indication of a patient’s need for altitude simulation (3,4).

The clinician’s second task is to decide whether the identified patients are able to tolerate the conditions of air travel. Here also, there are discrepant guidelines concerning the choice of test and how to interpret the results. The HAST artificially reduces inspired oxygen to similar levels experienced at 2438 m for 20 min by either giving a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.15 or by reducing atmospheric pressure to 565 Torr (75 KPa) in a hypobaric chamber; both methods are considered to be equivalent (6,7). The expected PaO2 at altitude (PaO2alt) is then determined from measurements of arterial blood gases (ABGs). The HAST is considered to be the ‘gold standard’; however, opinions differ as to whether a PaO2 of 55 mmHg or less (AMA) or 50 mmHg (ATS, ERS and VA) warrants the prescription of oxygen for flight. The HAST simulates the maximum drop in pressure expected during air travel, and has been demonstrated to produce oxygenation comparable with that observed during actual air travel (7–9).

Several investigators have developed predictive equations that estimate PaO2alt using measurements made at sea level (6,10–15); PaO2gr appears in all equations. Other variables include cabin altitude, inspired oxygen pressure at altitude, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) at sea level, health status, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). Guideline documents refer to equations as either a screening tool for recommending a HAST (ATS, ERS), or a replacement for HAST when it is unavailable (BTS, VA).

Finally, some airline medical departments and the AMA recommend the 50 m walk test as a sufficient estimate of fitness to fly (1,4).

The current study aimed to evaluate the latter methods of determining fitness to fly in patients with chronic lung disease. We propose that predictive equations and the 50 m walk test must be both highly specific and sensitive to be useful clinical tools. Our objectives were to determine the adequacy of screening recommendations at identifying patients at risk of hypoxemia at altitude, to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of published predictive equations compared with the HAST, and to analyze other possible predictors of the need for in-flight oxygen.

METHODS

Charts were reviewed at two university affiliated teaching hospital pulmonary function laboratories that performed altitude simulation testing. Consecutive patients who were not on supplemental oxygen were tested during a 10-month period. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario.

Altitude simulation was performed as previously described (11). For altitude simulation, patients inhaled a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.15 via a nonrebreathing mask for 20 min with concurrent pulse oximetry. Measurements of ABGs were taken from the radial artery after subjects had inhaled the hypoxic mixture for 20 min whereupon they recovered with supplemental oxygen. Only one centre took baseline ABGs for the HAST. For the other patients, baseline ABGs were taken within three months of the HAST, from outpatient visits only.

PaO2alt estimates derived from 16 predictive equations (Table 1) were compared with the PaO2alt measured during the HAST and each equation was evaluated for sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, positive and negative likelihood ratio and accuracy that considered a PaO2alt of 50 mmHg or less a positive result.

TABLE 1.

Predictive equations evaluated

| Equation | Author (reference) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PaO2alt = 0.410(PaO2gr) + 17.652 | Dillard et al (10) |

| 2 | PaO2alt = 0.417(PaO2gr) + 17.802 | Dillard et al (6) |

| 3 | PaO2alt = 22.8 – 2.74*feet + 0.68*PaO2gr | Gong et al (11) |

| 4 | PaO2alt = 20.38 – (3*cabinalt) + (0.67*PaO2gr) | Henry et al (12) |

| 5 | PaO2 FIO2 0.15 = PaO2 FIO2 0.21*0.54 + 4.7 | Seccombe et al (13) |

| 6 | PaO2alt = 1.59 + 0.98*PaO2gr + 0.0031*Alt – 0.000061*PaO2gr*Alt – 0.000065*PCO2gr*Alt + 0.000000092*Alt2 | Muhm (14) |

| 7 | PaO2alt = 46.23 + 3.02*PCO2gr – 0.0038*Alt + 30.57*HS – 0.48*PCO2gr*HS = 0.000064*Alt*HS – 0.05*PCO22 | Muhm (14) |

| 8 | PaO2alt = 2.14 + 0.97*PaO2gr + 0.006*Alt – 0.000081*PaO2gr*Alt – 0.000076*PCO2gr*Alt + 0.00043*Alt*HS | Muhm (14) |

| 9 | PaO2alt = 10.61 + 0.87*PaO2gr + 0.0004*Alt – 0.000033*PaO2gr*Alt – 0.000033*PCO2gr*Alt + 0.000027*Alt*HS | Muhm (14) |

| 10 | PaO2alt = 0.519 × PaO2gr + 11.855 × FEV1 (L) – 1.760 | Dillard et al (10) |

| 11 | PaO2alt = 0.453 × PaO2gr + 0.386 × FEV1 (% predicted) + 2.44 | Dillard et al (10) |

| 12 | PaO2alt = 0.294(PaO2gr) + 0.086(FEV1%) +23.211 | Dillard et al (6) |

| 13 | PaO2alt = 0.245(PaO2gr) + 0.171(FEV1/FVC%) + 21.028 | Dillard et al (6) |

| 14 | PaO2alt = 0.238(PaO2gr) + 20.098(FEV1/FVC) + 22.258 | Dillard et al (6) |

| 15 | PaO2alt = [PaO2gr] [(−1)(0.02002-0.00976FEV1)(PIO2gr – PIO2alt)] | Dillard et al (15) |

| 16 | PaO2alt = [PaO2gr] [(−1)(0.01731-0.00019FEV1%)(PIO2gr – PIO2alt)] | Dillard et al (15) |

The equation number is used to identify each equation within the text. Alt Altitude; cabinalt Cabin pressure at altitude; HS Pulmonary health status: 1 = normal, −1 = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FIO2 Fraction of inspired oxygen; FVC Forced vital capacity; PaO2alt Partial pressure of arterial oxygen at altitude; PCO2 Partial pressure of carbon dioxide at sea level; PIO2alt Inspired oxygen pressure at altitude; PaO2gr Partial pressure of arterial oxygen at ground level

If patients in our population did not meet the criteria specified by the equation’s authors, the equation was evaluated in the subset of our population who did meet the criteria. The following inclusion criteria relate to equations 3, 4, 5, 15 and 16 respectively (Table 1): FEV1 less than 80% of predicted and FEV1/FVC ratio less than 70%; COPD; PaO2 greater than 70 mmHg, SpO2 greater than or equal to 95%; and FEV1 greater than 60% of predicted.

Data from a 6 min walk test was obtained within three months of the HAST to evaluate the airline criteria of a successful 50 m walk for determining fitness to fly. The inclusiveness of the various guidelines was evaluated by determining how many patients would not have been tested according to each guideline, and of those, how many were hypoxemic after undergoing a HAST.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of both the PaO2 and the SpO2 at sea level were plotted to evaluate fitness to fly cut-off values. Finally, a multiple stepwise regression analysis was performed to determine if any values of FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, residual volume or diffusion capacity (DLCO) correlated strongly with PaO2 after HAST. Results were considered significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

The patients (n=27) had typical chronic lung disease of moderate severity. Three patients had cystic fibrosis, 22 had COPD, and two had cystic fibrosis and COPD. Demographic data are presented in Table 2. After a HAST, four patients had a PaO2 value of less than 50 mmHg and six had values of between 55 mmHg and 50 mmHg. The 50 mmHg cut-off was used for the purpose of the present paper; however, all 10 of these patients were advised to consider in-flight supplemental oxygen.

TABLE 2.

Demographic data

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD | n |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64±18 | 27 |

| Men, % | 57 | 27 |

| Height, cm | 163±10 | 25 |

| Weight, kg | 70±16 | 25 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, % | 93 | 27 |

| FVC, L | 2.48±1.02 | 20 |

| FVC, % predicted | 76±25 | 20 |

| FEV1, L | 1.41±0.71 | 20 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 58±22 | 20 |

| FEV1/FVC | 58±17 | 20 |

| FEV1/FVC, % predicted | 79±23 | 20 |

| Residual volume, L | 2.01±1.16 | 14 |

| Diffusion capacity, mL/min/mmHg | 12.19±5.73 | 13 |

| Baseline blood gases | ||

| SpO2, % | 95±3 | 27 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 38±5 | 27 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 75±10 | 27 |

| Post-HAST blood gases | ||

| SpO2, % | 89±3 | 27 |

| PCO2, mmHg | 37±4 | 27 |

| PO2, mmHg | 58±7 | 27 |

FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC Forced vital capacity; HAST Hypoxia altitude simulation test; PaCO2 Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide at sea level; PCO2 Partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2 Partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PO2 Partial pressure of oxygen; SpO2 Baseline saturation of peripheral oxygen

Table 3 presents an evaluation of each equation that was tested. Equations showed better or equivalent results when tested on their intended population than with the entire sample set. Equations 1 to 9 underestimated the PaO2alt, leading to high sensitivity but low specificity. In contrast, equations 15 and 16 overestimated the PaO2alt, resulting in high specificity but low sensitivity. These two equations did not identify any patients as needing in-flight oxygen. Equations 10 and 14 were low in both sensitivity and specificity.

TABLE 3.

Equation and 50 m walk test evaluation

| Equation | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Positive likelihood ratio | Negative likelihood ratio | Accuracy | Area under ROC curve | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 27 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.79 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 27 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 27 |

| 3* | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 2.20 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 12 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 27 |

| 4* | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 1.69 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 23 |

| 5 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 27 |

| 5* | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 17 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 27 |

| 7 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 27 |

| 8 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 27 |

| 9 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 27 |

| 10 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 20 |

| 11 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 20 |

| 12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 3.00 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 20 |

| 13 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 20 |

| 14 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20 |

| 15 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 20 |

| 15* | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 7 |

| 16 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 20 |

| 16* | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 7 |

A cut-off value of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) ≤ 50 mmHg was used to define positive cases.

Each equation was tested on the full sample as well as the portion of the sample that fit the inclusion criteria of the original author, if applicable. ROC Receiver operating characteristic

The 11 patients who performed a 6 min walk test covered (mean ± SD) 359±101 m, all passing the airline requirements for fitness to fly. Evaluations based on SpO2 during the 6 min walk test did not improve this test’s predictive value. Five patients had an SpO2 below 85% while walking, but of these, only two were identified by the HAST as needing supplemental in-flight oxygen. One interesting trend was that the four patients for whom the HAST recommended supplemental oxygen walked the shortest distance in the patient population (330 m or less in 6 min).

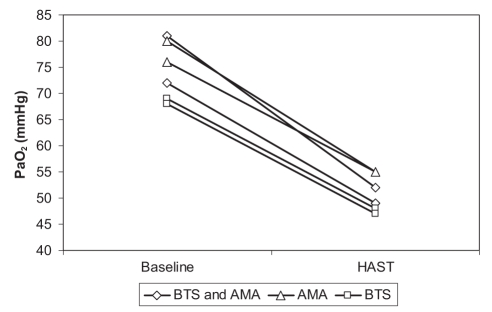

Of the 12 patients who the BTS considered fit to fly (SpO2 greater than 95%), three had a PaO2 of less than 50 mmHg after the HAST and one had a PaO2 of 52 mmHg. Four of the 16 subjects presumed fit to fly by the AMA (PaO2gr of 70 mmHg or higher) also benefited from the HAST (PaO2alt 55 mmHg or less), with one below 50 mmHg. Thus, 25% to 33% of the population presumed fit to fly required further investigation. Figure 1 shows the drop in PaO2 experienced by each of these six patients between room air and the HAST. Diagnosis of these patients revealed that three had COPD, two had cystic fibrosis and one patient had both. The drops in PaO2 observed in the two cystic fibrosis patients were not distinguishable from those of the three COPD patients.

Figure 1).

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) drop in six patients whom guidelines considered fit to fly. The patients were considered fit to fly by at least one of the criteria set by the British Thoracic Society (BTS; baseline saturation of peripheral oxygen [SpO2] >95% and the Aerospace Medical Association (AMA; PaO2 at ground level ≥70 mmHg). Three patients had a posthypoxia altitude simulation test (HAST) PaO2 of less than 50 mmHg, while the other three subjects had a PaO2 of between 50 mmHg and 55 mmHg

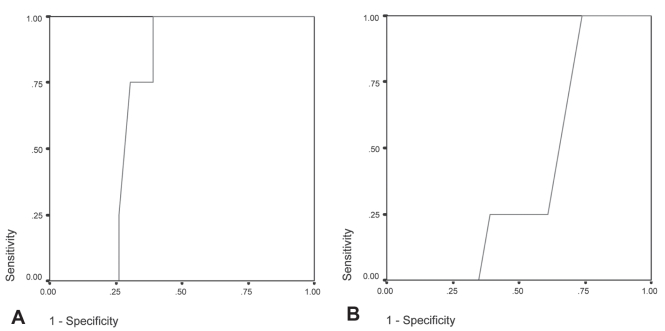

ROC curves are shown in Figure 2. Baseline PaO2, as validated against HAST outcome, gave an area under the ROC curve of 0.696±0.095 (P<0.13) and suggested that the cut-off yielding greatest accuracy was a PaO2 of 72 mmHg or less, at which point sensitivity was 1.00 and specificity was 0.61. Baseline SpO2, as validated against HAST outcome, gave an area under the ROC curve of 0.402±0.112 (P<0.55) and suggested a cut-off value for greatest accuracy of 96%, at which point sensitivity was 1.00 and specificity was 0.74. Each equation was also subjected to ROC analysis in comparison with the HAST results (Table 3). Based on the area under the ROC curve, equation 3 was the most accurate predictor evaluated but had poor overall predictive characteristics.

Figure 2).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of baseline partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) and resting baseline saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) related to the hypoxia altitiude simulation test (HAST) outcome (n=27). (A) ROC curve of PaO2 at ground level and HAST outcome gave an area under the curve of 0.696 (P=0.13). At a specificity of 100, PaO2 ≤72 mmHg. (B) ROC analysis of SpO2 at rest related to HAST outcome, gave an area under the curve of 0.402 and a SpO2 cut-off for recommending a HAST of 95% or lower

Regression analysis determined three variables that correlated with the ratio of PaO2alt to PaO2gr (r=0.45; P<0.009), DLCO (r=0.56; P<0.05) and FEV1% predicted (r=0.57; P<0.009). All other variables tested (age, FVC, FEV1/FVC and residual volume) showed no statistically significant correlations with PaO2alt.

After controlling for PaO2gr, DLCO remained significantly and independently associated with PaO2alt (r=0.60; P<0.04), as did FEV1% predicted (r=–0.48; P<0.04). Because the sample size allowed for the examination of two-variable interactions, the following new prediction equations were derived:

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that current guidelines concerning the need for detailed assessment of oxygen requirements at altitude need review. In the patients tested, neither SpO2 or PaO2gr was sufficiently sensitive or specific to determine the patients most in need of altitude simulation or further evaluation. Our results, like those of Christensen et al (16), show that using cut-offs to identify patients who are fit to fly without further examination misses up to one-third of individuals who will desaturate to a PaO2 of less than 50 mmHg. Furthermore, equations are poor predictors of PaO2 measured during altitude simulation procedures and, thus, are an unreliable means of determining a patient’s fitness to fly. Because no individual equation could consistently distinguish patients who needed oxygen from those who did not, we recommend against their use in preflight evaluation. Concern over this practice has been raised previously by authors reporting poor reproducibility of results (17–20). These equations have been accepted as interchangeable with other methods, despite the lack of validation. We suggest that the HAST should be used to evaluate all patients suspected to be at risk of becoming hypoxemic at altitude. Using the equations as a criteria for HAST selection is also a risky practice because our results showed that their predictions depended largely on which equation was used rather than on patient characteristics.

We demonstrated a correlation between FEV1 and PaO2alt. This second-order correlation has been reported several times (6,10,15) but the finding has not been consistently reproduced (21). Interestingly, our study suggests that DLCO and FEV1 are better predictors of PaO2alt than PaO2gr. This finding is consistent with the predictors of arterial desaturation in COPD patients during exercise (22).

We also found the 50 m walk test to be an unreliable predictor of fitness to fly because all of the evaluated patients who had available walk test data greatly exceeded this distance. We did find, however, that the patients in our pool who walked 330 m or less during the 6 min walk test all had a PaO2 of less than 50 mmHg after the HAST.

Several questions remain regarding the generalizability of the HAST results. Because the simulation lasts only 20 min, it is unclear whether a further drop in PaO2 can be expected on longer flights. While there is some evidence that this does not occur, patients may compensate for the reduced oxygen by increasing their respiratory rate (18). This could possibly become fatiguing in longer flights, resulting in a delayed decrease in respiratory rate and, consequently, a further drop in PaO2.

There is a need for more evidence on which to base guidelines in this field. Current guidelines vary, and among individual clinicians, the practice is even more diverse (23). For example, PaO2 in flight is considered safe if it is greater than 50 mmHg. This value was reported in the paper that first described the HAST test (11), and was subsequently incorporated into guideline documents and other publications (1,6,17,24,25). We find this value to be substantially lower than necessary, and speculate that patients with a PaO2 of between 50 mmHg and 55 mmHg may also benefit from in-flight oxygen.

Our ROC analysis of PaO2 and SpO2 criteria for HAST produced mixed results. Although both cut-offs coincided with guidelines, these findings were not statistically significant, and the areas under the ROC curves indicated poor predictive ability of these variables. We suggest more analyses such as these be performed to form a solid evidence base from which to draw guidelines.

Some limitations to our study must be noted. First, our sample size was small, reflecting the infrequent use of altitude simulation procedures to assess fitness to fly. We doubt that a larger sample size would significantly alter our major conclusions given the poor performance of screening recommendations and predictive equations. Second, our patients’ referral for this test indicates they were at a geographical advantage and had time to perform the test before travel; consequently, their results may only approximate those of the larger population. Although it is possible that they were at particular risk of hypoxemia in flight, this was not evident from any demographic, clinical or physiological characteristics at baseline, and the population was sufficiently diverse in HAST outcome to test the screening recommendation and predictive equations. Third, although the HAST is the gold standard for estimating in-flight hypoxia, it does not take into account the effects of additional stress and exercise performed at altitude. Finally, our population was not limited to patients with COPD but also included patients with restrictive processes. However, when these were excluded, our conclusions remained unchanged. Avenues for future research include consideration of underlying pulmonary diagnosis as a baseline variable in the clinical outcomes among disease entities, and the implications of increasing the use of the HAST from a cost perspective.

SUMMARY

Current screening recommendations do not identify all patients at significant risk for hypoxemia at altitude and predictive equations based on ground level variables cannot replace altitude simulation procedures when evaluating patient need for oxygen supplementation during airline flight.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emilio Perri, Myra Slutsky and Eva Leek for their administrative and technical assistance, and Edmee Franssen for her statistical advice. This research was supported, in part, by the Imperial Oil Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Managing passengers with respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. Thorax. 2002;57:289–304. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force. Standards for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with COPD 2004. <http://www.thoracic.org/go/copd> (Version current at October 13, 2006).

- 3.Lien D, Turner M. Recommendations for patients with chronic respiratory disease considering air travel: A statement from the Canadian Thoracic Society. Can Respir J. 1998;5:95–100. doi: 10.1155/1998/576501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical guidelines for airline travel, 2nd edn. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74(Suppl 5):A1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense . VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Outpatient Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillard TA, Moores LK, Bilello KL, Phillips YY. The preflight evaluation. A comparison of the hypoxia inhalation test with hypobaric exposure. Chest. 1995;107:352–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naughton MT, Rochford PD, Pretto JJ, Pierce RJ, Cain NF, Irving LB. Is normobaric simulation of hypobaric hypoxia accurate in chronic airflow limitation? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):1956–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly PT, Swanney MP, Seccombe LM, Frampton C, Peters MJ, Beckert L. Air travel hypoxemia vs. the hypoxia inhalation test in passengers with COPD. Chest. 2008;133:920–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly PT, Swanney MP, Frampton C, Seccombe LM, Peters MJ, Beckert LE. Normobaric hypoxia inhalation test vs. response to airline flight in healthy passengers. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:1143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillard TA, Berg BW, Rajagopal KR, Dooley JW, Mehm WJ.Hypoxemia during air travel in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Ann Intern Med 1989. 1;111362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong H, Jr, Tashkin DP, Lee EY, Simmons MS. Hypoxia-altitude simulation test. Evaluation of patients with chronic airway obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:980–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry JN, Krenis LJ, Cutting RT. Hypoxemia during aeromedical evacuation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1973;136:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seccombe LM, Kelly PT, Wong CK, Rogers PG, Lim S, Peters MJ. Effect of simulated commercial flight on oxygenation in patients with interstitial lung disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2004;59:966–70. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.022210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muhm JM. Predicted arterial oxygenation at commercial aircraft cabin altitudes. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75:905–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dillard TA, Rosenberg AP, Berg BW. Hypoxemia during altitude exposure. A meta-analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1993;103:422–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.2.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen CC, Ryg M, Refvem OK, Skjonsberg OH. Development of severe hypoxaemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at 2,438 m (8,000 ft) altitude. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:635–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15463500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson AO. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Fitness to fly with COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:729–32. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akero A, Christensen CC, Edvardsen A, Skjonsberg OH. Hypoxaemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients during a commercial flight. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:725–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00093104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen CC, Ryg MS, Refvem OK, Skjonsberg OH. Effect of hypobaric hypoxia on blood gases in patients with restrictive lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:300–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00222302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin SE, Bradley JM, Buick JB, Bradbury I, Elborn JS. Flight assessment in patients with respiratory disease: Hypoxic challenge testing vs. predictive equations. QJM. 2007;100:361–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson AG, Hartung TK, Innes JA. Laboratory assessment of fitness to fly in patients with lung disease: A practical approach. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:214–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b06.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owens GR, Rogers RM, Pennock BE, Levin D.The diffusing capacity as a predictor of arterial oxygen desaturation during exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease N Engl J Med 1984. 10;3101218–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coker RK, Partridge MR. Assessing the risk of hypoxia in flight: The need for more rational guidelines. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:128–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15112800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: A summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong H., JrAdvising patients with pulmonary diseases on air travel Ann Intern Med 1989. 1;111349–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]