Abstract

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) has become an important clinical tool to evaluate exercise capacity and predict outcome in patients with heart failure and other cardiac conditions. It provides assessment of the integrative exercise responses involving the pulmonary, cardiovascular and skeletal muscle systems, which are not adequately reflected through the measurement of individual organ system function. CPET is being used increasingly in a wide spectrum of clinical applications for evaluation of undiagnosed exercise intolerance and for objective determination of functional capacity and impairment. This review focuses on the exercise physiology and physiological basis for functional exercise testing and discusses the methodology, indications, contraindications and interpretation of CPET in normal people and in patients with heart failure.

Keywords: exercise test, heart failure, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, exercise physiology, anaerobic threshold

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) provides assessment of the integrative exercise responses involving the pulmonary, cardiovascular, haematopoietic, neuropsychological, and skeletal muscle systems, which are not adequately reflected through the measurement of individual organ system function. This non‐invasive, dynamic physiological overview permits the evaluation of both submaximal and peak exercise responses, providing the doctor with relevant information for clinical decision making. CPET is increasingly being used in a wide spectrum of clinical applications for the evaluation of undiagnosed exercise intolerance and for the objective determination of functional capacity and impairment. Its use in patient management is increasing with the understanding that resting pulmonary and cardiac function testing cannot reliably predict exercise performance and functional capacity and that overall health status correlates better with exercise tolerance than with resting measurements.1

CPET involves measurements of respiratory oxygen uptake (Vo2), carbon dioxide production (Vco2), and ventilatory measures during a symptom‐limited exercise test.

Physiology of exercise

Peak exercise capacity is defined as “the maximum ability of the cardiovascular system to deliver oxygen to exercising skeletal muscle and of the exercising muscle to extract oxygen from the blood”.2 Consequently, exercise tolerance is determined by three factors: pulmonary gas exchange; cardiovascular performance, including the peripheral vascular tree; and skeletal muscle metabolism.

The Fick equation

Understanding the Fick equation is of paramount importance for appreciating the utility of functional exercise testing. At rest, the Fick equation states that oxygen uptake (Vo2) equals cardiac output times the arterial minus mixed venous oxygen content:

Vo2 = (SV × HR) × (Cao2 − Cvo2)

where SV is the stroke volume, HR is the heart rate, Cao2 is the arterial oxygen content, and Cvo2 is the mixed venous oxygen content. Oxygen uptake is often normalised for body weight and expressed in units of ml O2/kg/min. One metabolic equivalent (MET) is the resting oxygen uptake in a sitting position and equals 3.5 ml/kg/min.

At maximal exercise, the Fick equation is expressed as follows:

Vo2max = (SVmax × HRmax) × (Cao2max − Cvo2max)

This reflects the maximal ability of a person to take in, transport and use oxygen. It defines that person's functional aerobic capacity. Vo2max has become the preferred laboratory measure of cardiorespiratory fitness and is the most important measurement during functional exercise testing. In healthy people, a Vo2 plateau occurs at near maximal exercise. This plateau in Vo2 has traditionally been used as the best evidence of Vo2max. It represents the maximal achievable level of oxidative metabolism involving large muscle groups. However, in clinical testing, a clear plateau may not be achieved before symptom limitation of exercise. Consequently, peak Vo2 (PVo2) is often used as an estimate of Vo2max.3

Exercise intolerance

Exercise intolerance (functional aerobic impairment) is defined as an abnormally low Vo2max. This can occur with any factor that affects one or more of the four variables of the Fick equation that determine Vo2max: a reduction in maximal heart rate, maximal stroke volume, or maximal Cao2; or an increase in rest Cvo2. As an example, one of the factors limiting Vo2max in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) is the marked reduction in stroke volume response to exercise with smaller reductions in maximal heart rate and maximal arterial minus mixed venous oxygen content (Cao2max − Cvo2max).4,5,6 On the other hand, diseases of the lungs, skeletal muscles and haematological system often have a profound effect on Vo2max by affecting arterial or mixed venous oxygen content.

Exercise training in healthy people

Several important changes occur in the Fick equation as a healthy person goes from rest to maximal exercise before and after exercise training7:

The Vo2max response to exercise is linear until maximal Vo2 is achieved. In many people, a plateau is reached at near maximal exercise, beyond which the Vo2 does not change. Exercise training enables the person to achieve a greater maximal workload and a higher Vo2max.

After training, the heart rate is lower at rest and at each stage of exercise, but the maximal heart rate does not change. This approximates “220 bpm – age”.7

The stroke volume response is curvilinear, increasing early in exercise with little change thereafter. The training effect increases the resting stroke volume and the stroke volume at each workload.

The a−v O2 content difference widens as the mixed venous O2 content falls since arterial O2 content does not change in normal subjects. The maximal a−v O2 content difference increases after training.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

Several different methods exist for measuring ventilation and respiratory gas parameters during exercise. Most clinical systems rely on breath‐by‐breath analysis techniques because they provide the best measures of the metabolic response to exercise. A non‐rebreathing valve is connected to a mouthpiece to prevent mixing of inspired and expired air (fig 1). Oxygen and carbon dioxide gas analysers are usually incorporated in a “metabolic cart” designed specifically for functional testing. Respiratory volumes are computed by integrating the air flow signals over the time of inspiration and expiration. Average minute volumes are derived from the breath‐by‐breath data multiplied by the respiratory rate.

Figure 1 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing machine using the cycle ergometry. A non‐rebreathing valve is connected to a mouthpiece with continuous ECG and blood pressure monitoring. Resuscitation equipment on hand. Informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

CPET protocols

Many different protocols are used for functional testing. The purpose of the test and the functional capabilities of the patient determine the choice of protocol. In evaluating patients with CHF, both bicycle and treadmill protocols have been used. The rate of workload progression is somewhat arbitrary, although it has been suggested that optimal exercise duration for functional assessment on the bicycle is between 8 and 17 minutes.8 Bicycle work is quantified in watts (W) or in kilopod metres/min (kpm/min; 1 W = ∼6 kpm/min). The initial workload for patients with patients with CHF is usually 20–25 W and increased by 15–25 W every 2 minutes until maximal exertion is reached. Alternatively, the workload can be computer controlled for electronically braked bicycle ergometers, and a ramp protocol (eg, 10 W/min) is often used. The modified Naughton protocol is recommended for treadmill exercise testing in patients with heart failure.9 This protocol is designed to increase the workload by approximately 1 MET (3.5 ml O2/kg/min) for each 2‐minute stage.

Treadmill exercise testing has several advantages over cycle ergometry (table 1),1,10 and for most people, treadmill walking is a more familiar activity than cycling. It involves a larger muscle mass and more work against gravity. Consequently, PVo2 is, on average, 5–10% higher on the treadmill than on a cycle ergometer. Holding onto the treadmill handrails usually decreases the metabolic cost of treadmill walking and should be discouraged if possible. A cycle ergometer is less prone to induce noise artefacts with better quantification of the metabolic cost. Generally it is less expensive and requires less space than the treadmill.

Table 1 Exercise equipment: cycle ergometry vs treadmill.

| Variable | Cycle | Treadmill |

|---|---|---|

| Peak oxygen content (PVo2) | Lower | Higher |

| Work rate measurement | Yes | No |

| Blood gas collection | Easier | More difficult |

| Noise and artefacts | Less | More |

| Safety | Safer | Less safe? |

| Weight bearing in obese subjects | Less | More |

| Degree of leg muscle training | Less | More |

| More appropriate for | Patients | Active normal subjects |

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

Patients with heart disease require continuous ECG monitoring and frequent blood pressure measurements during exercise testing. Since verbal communication is usually not possible with the mouthpiece apparatus, hand signals are usually used by the patient during exercise.

Oxygen uptake and peak oxygen uptake

Oxygen uptake (Vo2) is determined by cellular O2 demand up to some level that equates to maximal rate of O2 transport, which then is determined by that maximal rate of transport. As Vo2 increases with increasing external work, one or more of the determinants of Vo2 approach limitations (eg, stroke volume, heart rate, or tissue extraction), and Vo2 versus work rate may begin to plateau. This plateau in Vo2 has traditionally been used as the best evidence of Vo2max.

The main determinants of a normal PVo2 are genetic factors, quantity of exercising muscle, age, sex and body size. It can also be affected by training and patient motivation. PVo2 should be expressed in absolute values (l/min) and as a percentage of the predicted value. Vo2 can increase from a resting value of about 3.5 ml/kg/min (about 250 ml/min in an average person) to PVo2 values about 15 times the resting value (30–50 ml/kg/min). Athletes may attain values over 20 times their resting values (up to 80 ml/kg/min).

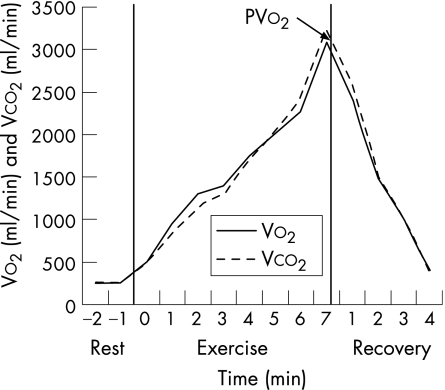

Figure 2 is an example of a normal CPET using the Bruce protocol. Table 2 shows the normal values of variables derived from CPET.1

Figure 2 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in a healthy 49‐year‐old man using the Bruce protocol. The progressive linear increase in Vo2 is noted, reaching a steady state after 2 minutes in each of the first two stages. Peak Vo2 (PVo2) was 3.09 l/min.

Table 2 Normal cardiopulmonary exercise testing variables.

| Variables | Normal value |

|---|---|

| Peak oxygen content (PVo2) | >84% Predicted |

| Ventilatory anaerobic threshold (VAT) | >40% PVo2 (40–80%) |

| Maximum heart rate (HRmax) | >90% Age predicted |

| Heart rate reserve (HRR) | <15 Beats/min |

| Blood pressure (BP) | <220/90 |

| O2 pulse (Vo2/HR) | >80% |

| Ventilatory reserve (VR) | MVV−VEmax >11 litres or VEmax/MVV × 100 <85% |

| Respiratory rate (RR) | <60 Breaths/min |

| Minute ventilation/carbon dioxide output ratio (VE/Vco2) at VAT | <34 |

MVV, maximal voluntary ventilation; VE, expired ventilation.

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

Respiratory exchange ratio

The ratio of carbon dioxide output/oxygen uptake (Vco2/Vo2) is called the gas exchange ratio or respiratory exchange ratio (RER). Under steady state conditions, the RER equals the respiratory quotient (RQ). The RQ value is determined by the fuels used for metabolic processes. An RQ of 1 indicates metabolism primarily of carbohydrates, whereas an RQ of <1 indicates a mixture of carbohydrates with fat (RQ about 0.7) or protein (RQ about 0.8). The term “RQ” is often reserved for expressing events at the tissue level which are difficult to measure. The term “RER” is usually measured by gas exchange at the mouth and in true steady state, the blood and gas transport systems keep pace with tissue metabolism; thus, the RER can be used as a rough index of metabolic events (RQ). RER increases during exercise owing to either the buffered lactic acid or hyperventilation (usually towards the end of exercise).

Ventilatory anaerobic threshold

The ventilatory anaerobic threshold (VAT), formerly referred to as the anaerobic threshold, is an index used to estimate exercise capacity. During the initial (aerobic) phase of CPET, which lasts until 50–60% of Vo2max is reached, expired ventilation (VE) increases linearly with Vo2 and reflects aerobically produced CO2 in the muscles. Blood lactate levels do not change substantially during this phase, since muscle lactic acid production is minimal.

During the latter half of exercise, anaerobic metabolism occurs because oxygen supply cannot keep up with the increasing metabolic requirements of exercising muscles. At this time, there is a significant increase in lactic acid production in the muscles and in the blood lactate concentration. The Vo2 at the onset of blood lactate accumulation is called the lactate threshold or the VAT. The VAT is also defined as the point at which minute ventilation increases disproportionately relative to Vo2, a response that is generally seen at 60–70% of Vo2max.

The VAT is a useful measure as work below this level encompasses most daily living activities. The ability to achieve the VAT can help distinguish cardiac and non‐cardiac (pulmonary or musculoskeletal) causes of exercise limitation, since patients who fatigue before reaching VAT are likely to have a non‐cardiac problem.11,12 This is not universally true, as patients with mitral stenosis, for instance, often stop exercising before reaching VAT, while on the other hand patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease commonly pass the VAT.

Several methods are available to determine the VAT, and these can be classified as either invasive (measurement of lactic acid or bicarbonate) or non‐invasive. Invasive estimation of the VAT is usually done by direct blood sampling and is rarely used in a clinical setting since determination of the point of rise in lactate (or the reciprocal drop in bicarbonate) requires multiple blood samples. When this method is used, the “VAT” is defined as the Vo2 at which blood lactate level increases or, alternatively, when the bicarbonate starts to drop. However, the precise definition remains controversial.1 Non‐invasive methods require observing the pattern of change in Vco2 and VE relative to Vo2 as exercise intensity increases. The two main non‐invasive methods for estimating the VAT are:13

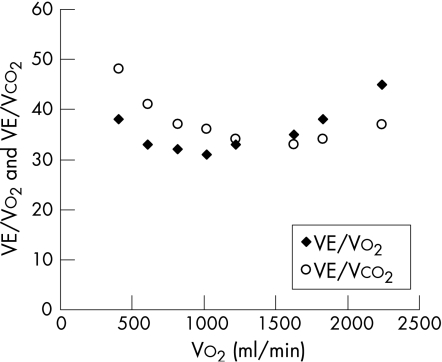

The ventilatory equivalents method (fig 3): the VAT is the Vo2 at which the ventilatory equivalent for O2 (VE/Vo2 ratio) and end‐tidal oxygen tension (PET O2) begin to increase systematically without an immediate increase in the ventilatory equivalent for CO2 (VE/Vco2) and end‐tidal CO2 tension (PET CO2).

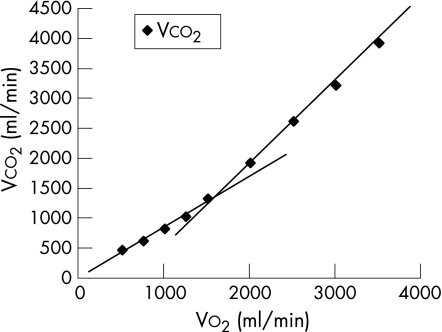

The V‐slope method (fig 4): the VAT is defined as the Vo2 at which the rate of increase in Vco2 relative to Vo2 increases in the absence of hyperventilation.14 The VAT determined by this method is a more reproducible estimate.

Figure 3 Determination of the ventilatory anaerobic threshold (VAT) by the ventilatory equivalents method. The VAT is the Vo2 (1400 ml) at which the ventilatory equivalent for O2 (VE/Vo2 ratio) begins to increase systematically without an immediate increase in the ventilatory equivalent for CO2 (VE/Vco2).

Figure 4 Determination of the ventilatory anaerobic threshold (VAT) by the V‐slope method in a healthy 49‐year‐old man. The VAT is the point at which the slope of the relative rate of increase in Vco2 relative to Vo2 changes. In this patient, it occurred at a Vo2 of 1.5 l/min, or 49% of PVo2.

Unfortunately, there is considerable inter‐ and intraobserver variability in the visual detection of the onset of anaerobic metabolism from the breath‐by‐breath data.15

Indications and contraindications of CPET

The ACC/AHA Update of Practice Guidelines for Exercise Testing, published in 2002, listed the indications for ordering a functional Vo2 exercise test (table 3).16,17 Contraindications for CPET are listed in (table 4). Although CPET provides excellent risk stratification in primary pulmonary hypertension, caution is advised when exercising these patients owing to the increased risk of sudden death as pulmonary pressure increases with exercise.18

Table 3 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary exercise testing.

| Class | Indication |

|---|---|

| I (indicated) | 1 Evaluation of exercise capacity and response to treatment in patients with heart failure who are being considered for heart transplantation |

| 2 Assistance in the differentiation of cardiac versus pulmonary limitations as a cause of exercise‐induced dyspnoea or impaired exercise capacity when the cause is uncertain | |

| IIa (good supportive evidence) | Evaluation of exercise capacity when indicated for medical reasons in patients for whom the estimates of exercise capacity from exercise test time or work rate are unreliable |

| IIb (weak supportive evidence) | 1 Evaluation of the patient's response to specific therapeutic interventions in which improvement of exercise tolerance is an important goal or end point |

| 2 Determination of the intensity for exercise training as part of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation | |

| III (not indicated) | Routine use to evaluate exercise capacity |

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

Table 4 Absolute and relative contraindications for cardiopulmonary exercise testing.

| Absolute | Relative |

|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction (3–5 days) | Left main coronary stenosis or its equivalent |

| Unstable angina | Moderate stenotic valvular heart disease |

| Uncontrolled arrhythmias causing symptoms or haemodynamic compromise | Severe untreated arterial hypertension at rest or haemodynamic compromise (>200 mm Hg systolic, >120 mm Hg diastolic) |

| Syncope | Tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias |

| Active endocarditis | High‐degree atrioventricular block |

| Acute myocarditis or pericarditis | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis | Significant pulmonary hypertension |

| Uncontrolled heart failure | Advanced or complicated pregnancy |

| Acute pulmonary embolus or pulmonary infarction | Electrolyte abnormalities |

| Thrombosis of lower extremities | Orthopaedic impairment that compromises exercise performance |

| Suspected dissecting aneurysm | |

| Uncontrolled asthma | |

| Pulmonary oedema | |

| Room air desaturation at rest ⩽85%* | |

| Respiratory failure | |

| Acute non‐cardiopulmonary disorder that may affect exercise performance or be aggravated by exercise (ie, infection, renal failure, thyrotoxicosis) | |

| Mental impairment leading to inability to cooperate |

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

Indications for terminating CPET

Symptoms at maximal exercise that result in test termination include muscle fatigue, exhaustion, extreme dyspnoea, and light‐headedness. Cardiac arrhythmias are usually not an indication to stop the test unless sustained tachyarrhythmias develop.

A decrease in systolic blood pressure below the resting pressure is a sign of insufficient increase in cardiac output to compensate for the exercise‐induced systemic vasodilatation, and is an indication to stop the test. Other indications for CPET termination are given in (table 5).

Table 5 Indications for exercise termination.

| Chest pain suggestive of ischaemia |

| Ischaemic ECG changes |

| Complex ectopy |

| Second‐ or third‐degree heart block |

| Fall in systolic pressure >20 mm Hg from the highest value during the test |

| Hypertension (>250 mm Hg systolic; >120 mm Hg diastolic) |

| Severe desaturation: Spo2 ⩽80% when accompanied by symptoms and signs of severe hypoxaemia |

| Sudden pallor |

| Loss of coordination |

| Dizziness or faintness |

| Signs of respiratory failure |

| Mental confusion |

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

CPET and heart failure (HF)

Exercise intolerance is one of the main manifestations of HF, varying directly with the severity of the disease. Thus, decreased maximal exercise capacity is associated with higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, worse symptoms, poor quality of life and decreased patient survival. Exercise training may increase functional capacity and therefore improve the quality of life. Its effect on survival is unclear at present.19

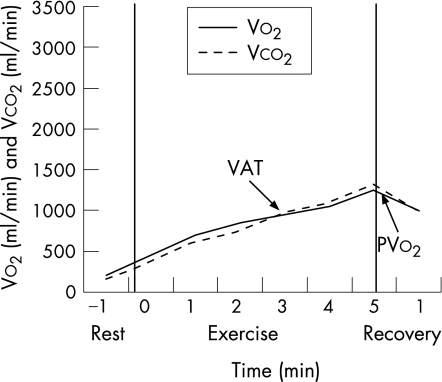

Exercise capacity is reduced even in mild HF. The cardiac output may be relatively normal at rest, but usually does not increase adequately with even mild exertion.20 As in normal subjects, PVo2 in HF is directly related to cardiac output and muscle blood flow at peak exercise. However, the inability to appropriately increase cardiac output results in insufficient increase in perfusion to exercising muscles, which can cause early anaerobic metabolism, muscle fatigue, and eventually can contribute to muscle wasting.21 Patients with HF typically do not achieve a true Vo2max, therefore the term “peak Vo2” is more appropriate and is more often used. Figure 5 shows a typical example of CPET in a patient with HF.

Figure 5 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in a 46‐year‐old man with cardiomyopathy in NYHA class III. A modified Bruce protocol was used. The patient reached a PVo2 of 14 ml/kg/min (4 METs), 42% of predicted for age, gender, and weight. The ventilatory anaerobic threshold occurred at a Vo2 of 955 ml/min (slopes intersection point). This blunted cardiopulmonary response is typical in severe cardiomyopathy. The patient also had blunting in his heart rate response, with an HRmax of 120 bpm. He was listed for cardiac transplantation. HR, heart rate; METs, metabolic equivalents.

CPET has an important role in the diagnosis, quantification of symptoms, prognosis and assessment of the success of therapeutic interventions in patients with HF.22,23

Factors contributing to exercise intolerance in HF

Several factors may contribute to exercise intolerance in patients with HF:24

The inotropic and chronotropic response to catecholamines is reduced; this defect is due, at least in part, to downregulation of β‐receptors in the presence of chronically raised circulating catecholamine levels.

Augmentation of stroke volume by the Starling mechanism may be limited by diastolic dysfunction or pericardial constraint.

In contrast with normal subjects, exercise is associated with a higher increase in the pulmonary wedge pressure. This can exacerbate pulmonary congestion, thereby causing dyspnoea and limiting exercise capacity.

The presence of pulmonary hypertension and increased pulmonary vascular resistance can reduce the cardiac output response to exercise, leading to impaired exercise capacity.25

Concurrent mitral regurgitation.

Peripheral factors affecting skeletal muscles are often present, limiting the metabolic capacity of these muscles. This includes abnormalities of the endothelial function, ergoreflex activation, vasodilatory capacity and distribution of cardiac output.26

Use of CPET in assessing HF severity

The CPET is a global test of a patient's cardiorespiratory capacity, since it reflects the entire oxygen transport system beginning with the lungs and ending with the skeletal muscles. This objective assessment offers advantages over other methods in assessing the severity of HF:

The NYHA classification of functional impairment in HF is not always accurate since it is subjective rather than objective.

Resting central haemodynamics do not always correlate well with functional impairment measured during exercise testing.

The symptoms of exercise intolerance in HF, such as dyspnoea, fatigue, or both, result from a complex interplay of mechanisms originating from both the central and peripheral components of the oxygen transport system. These symptoms are non‐specific and may also be due to the side effects of the drugs or to other coexisting conditions that may or may not be related to the underlying heart disease.

Therefore, CPET is often helpful for classifying disease severity for treatment decisions and in the differential diagnosis of exercise intolerance and symptoms of dyspnoea and fatigue (table 6).1

Table 6 American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians: usual cardiopulmonary exercise response patterns.

| Measurement | Heart failure | COPD | ILD | Pulmonary vascular disease | Obesity | Deconditioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVo2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ for actual, N for ideal weight | ↓ |

| VAT | ↓ | N /↓/indeterminate | N or ↓ | ↓ | N | N or ↓ |

| Peak HR | Variable, N in mild | ↓, N in mild | ↓ | N /slightly ↓ | N /slightly ↓ | N /slightly ↓ |

| O2 Pulse | ↓ | N or ↓ | N or ↓ | ↓ | N | ↓ |

| VE/MVV × 100 | N or ↓ | ↑ | N or ↑ | N | N or ↑ | N |

| VE/Vco2 at VAT | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| VD/VAT | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| Pao2 | N | Variable | ↓ | ↓ | N/may ↑ | N |

| P(A−a)o2 | Usually N | Variable, usually ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | May ↓ | N |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, heart rate; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MVV, maximum voluntary ventilation; N, normal; P(A–a)o2, alveolar–arterial difference for oxygen pressure; PVo2, peak oxygen uptake; VAT, ventilatory anaerobic threshold; VD/VAT, ratio of physiological dead space to tidal volume; VE, minute ventilation; Vco2, carbon dioxide output.

Adapted from ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing.1

CPET in predicting the prognosis in HF

The identification of patients at high risk of HF is of utmost importance in order to guide their pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatment (device‐related treatments, heart transplantation).27,28,29 CPET, when properly performed, provides the best objective measurement of peak functional capacity, and has become an important clinical tool in defining the severity of HF and in predicting outcome.30 The most relevant measures derived from CPET which have direct impact on decision making and the management plan in patients with HF are as follows:31

Peak oxygen consumption (PVo2)

There is extensive evidence supporting the use of PVo2 in stratifying the risk in patients with chronic HF. The study by Mancini et al is considered to be the cornerstone of the documentation of the prognostic power of PVo2 in this group of patents.32 In the study 116 consecutive male patients with CHF referred for heart transplantation were divided into the following three groups:

Patients with PVo2 of <14 ml/kg/min who had been accepted for heart transplantation.

Patients with PVo2 of ⩾14 ml/kg/min who were considered too well for transplantation.

Patients with PVo2 of <14 ml/kg/min but with significant comorbidity that precluded heart transplantation.

The 1‐year survival rates in groups 1, 2 and 3 were 48%, 94% and 47%, respectively. Of note, a PVo2 of <10 ml/kg/min was associated with significantly poorer predicted survival. The results of this study were adopted by the AHA/ACC consensus statement on the selection and treatment of candidates for heart transplantation.33 This consensus statement emphasised that once maximal treatment has been instituted and maintained, PVo2 has a predictive role and that for patients with PVo2 <14 ml/kg/min, it is important to prove that exercise testing was truly maximal by documenting achievement of the VAT at approximately 50–70% of PVo2.

As the value of PVo2 can be influenced by many factors other than the severity of CHF, the PVo2 value adjusted for these factors should theoretically improve the predictive accuracy. Stelken et al34 retrospectively studied 181 patients with CHF in order to compare the percentage achieved of the predicted PVo2, taking into account age, gender, and weight, with the traditionally used absolute PVo2 measured in ml/kg/min. During the 12‐month follow‐up, non‐survivors achieved a lower percentage of the predicted PVo2 and a lower absolute PVo2 than survivors, and multivariate analysis showed that a value <50% of the predicted PVo2 was the strongest predictor of cardiac events, better than the cut‐off absolute value of PVo2 of <14 ml/kg/min. Aaronson and Mancini refuted these results in another study.35 Osman et al have documented that the adjustment of PVo2 to lean body weight provides greater prognostic value than the traditional standard PVo2. Lean PVo2, either as a continuous variable or using a cut‐off value of ⩽19 ml/kg/min, was a better predictor of outcome than unadjusted PVo2 in 225 patients with chronic HF.36

Ventilatory anaerobic threshold

The VAT has been proposed as a submaximal index of exercise capacity, independent of the patient's motivation. A failure to reach the VAT strongly suggests poor motivation or non‐cardiovascular limitation of exercise tolerance. The VAT is undetectable in a large proportion of patients with CHF, especially in those with reduced exercise tolerance, restricting the prognostic and decisional value of PVo2.37

Opasich et al evaluated the predictive role of PVo2 in 505 male patients with CHF in whom VAT had and had not been identified.38 When the VAT was detected, the cardiac event rates were:

59% in patients with PVo2 values of ⩽10 ml/kg/min

32% in patients with PVo2 values of >10 to ⩽14 ml/kg/min

32% in patients with PVo2 values of >14 to ⩽18 ml/kg/min

15% in patients with PVo2 values of >18 ml/kg/min.

Therefore, when VAT is detected, patients with a PVo2 of <10 ml/kg/min have a high event rate, whereas those with a PVo2 of >18 ml/kg/min have a good prognosis. Patients with intermediate functional capacity (PVo2 10–18 ml/kg/min) fall into a range in which PVo2 does not provide predictive or decisional information.

When VAT was not detected, the event rate was 46% in patients with PVo2 of ⩽10 ml/kg/min, and was almost identical among those with PVo2 values of >10 to ⩽14 ml/kg/min, >14 to ⩽18 ml/kg/min, and >18 ml/kg/min (29%, 23% and 22%, respectively). Thus, When the VAT is undetectable, patients with PVo2 of <10 ml/kg/min have a high risk of events; and for those with PVo2 >10 ml/kg/min, the risk stratification is considered to be inconclusive and the replication of CPET is recommended.

Ventilatory expired gas parameters (VE/Vco2slope)

Recently, the VE/Vco2 slope has been proposed as an alternative prognostic indicator in patients with CHF. This dimensionless ratio indicates how many litres of air are being breathed to eliminate 1 litre of CO2. An abnormally high relationship between minute ventilation (VE) and carbon dioxide output (Vco2) (VE/Vco2 slope) is associated with a poor outcome. Chua et al reported that a VE/Vco2 slope of >34 was associated with worse prognosis in 173 patients with chronic HF,39 and Kleber et al selected a VE/Vco2 slope that was >130% of the age adjusted and sex‐adjusted value as the best predictive cut‐off point in 142 patients.40 MacGowan et al substantiated that the combination of a peak VE/Vco2 slope of >50 and a peak Vo2 of ⩽15 ml/kg/min was associated with an 82% mortality rate in 104 patients with chronic HF.41 Finally, Robbins et al found that a VE/Vco2 slope of ⩾44.7 at peak exercise was better than a peak Vo2 of ⩽13.9 ml/kg/min in predicting 18‐month survival.42

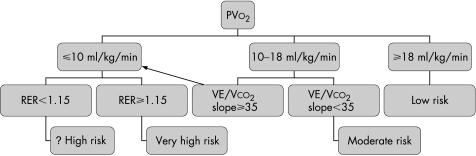

Recommended risk stratification algorithm

Taking into account the above mentioned measures derived from CPET to stratify risk for patients with HF and results from other trials,43,44 Corra and Mezzani proposed a new risk stratification algorithm (fig 6).31 This algorithm is structured on a multiparametric decoding scrutiny employing the stepwise introduction of PVo2, VE/Vco2slope, and peak RER. They divided patients with CHF into the following three groups:

Figure 6 A new prognostic algorithm that is structured on a multiparametric decoding scrutiny employing the stepwise introduction of PVo2, VE/Vco2 slope, and peak respiratory exchane ratio (RER). The arrow indicates that patients with intermediate exercise capacity (ie, PVo2 of >10 and <18 ml/kg/min) and excessive ventilatory response (ie, VE/Vco2 slope of ⩾35) have a total mortality rate that is comparable to that detected with a PVo2 of ⩽10 ml/kg/min (whole population). (Adapted from Corra and Mezzani31.)

PVo2 of ⩽10 ml/kg/min identifies high‐risk patients. The peak RER can correctly discriminate outcome, as those reaching an RER of at least 1.15 at peak effort have a higher risk, whereas those who do not attain a peak RER of 1.15 have a prognosis comparable to that of patients with a better functional capacity.

PVo2 of ⩾18 ml/kg/min is compatible with a fairly good long‐term prognosis.

PVo2 between 10 and 18 ml/kg/min indicates a moderate risk of cardiac events. A VE/Vco2slope of ⩾35 allows the identification of those patients with worse outcomes.

The VE/Vco2 slope yields an efficient predictive contribution for almost one‐quarter of patients with moderate chronic HF. The attainment of a peak RER of ⩾1.15 allows the identification of nearly half of patients with severe exercise intolerance with “true” low peak aerobic power, who are thus at high risk. This stepwise process can assist doctors in clinical decision making by describing a reliable risk for the individual patient.

CPET data and its reporting

The reporting of CPET should clearly show the indication as well as the beginning and end of exercise. Table 7 summarises the information that should be included in the final report, and an example of a CPET data report is available online as supplementary material (see http://heart.bmj.com/supplemental).

Table 7 Summary of the data that should be included in the cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) final report.

| Pretest information |

| • Reason for test |

| • General information: age, height, weight |

| • Pretest diagnoses, drugs, resting ECG and BP |

| Exercise modality and equipment |

| • Treadmill vs cycle ergometer |

| • Exercise protocol: ramp, incremental |

| • Modality of gas sampling: mask vs mouthpiece |

| Observations during exercise |

| • Reason(s) for termination |

| • Symptoms and complications |

| • Subjective assessment of effort |

| • Gas exchange and ventilatory data at peak and at VAT(if determined): absolute and percentage relative to reference |

| • HR, BP, and ECG changes |

| CPET interpretation |

| • Presence and severity of functional impairment |

| • Probable cause of functional impairment |

| • Comparison with previous functional evaluation if available |

Adapted from reference46.

BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; VAT, ventilatory anaerobic threshold.

Conclusions

CPET is a global test of the cardiorespiratory capacity that reflects the entire oxygen transport system starting with the lungs and ending with the skeletal muscles. Interpretation of CPET can be a complex task; however, PVo2 derived from CPET is a strong and independent factor in determining the prognosis of patients with CHF. In the past few years, it has been discovered that a single arbitrary cut‐off point for PVo2 may be unlikely to describe the true risk of events, and that a stepwise approach may be more helpful. Specific research is still needed to confirm the importance of a stepwise multiparametric interpretation of CPET. Finally, CPET has an important role as part of a holistic approach to the assessment and management of cardiac patients.

Supplementary material available online at http://heart.bmj.com/supplemental

Abbreviations

CHF - congestive heart failure

CPET - cardiopulmonary exercise testing

HF - heart failure

MET - metabolic equivalent

NYHA - New York Heart Association

PVo2 - peak Vo2

RER - respiratory exchange ratio

RQ - respiratory quotient

VAT - ventilatory anaerobic threshold

Footnotes

This is a reprint of a paper that appeared in Heart, October 2007, Volume 93, pages 1285–92. Reprinted with kind permission of the authors and publisher.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Supplementary material available online at http://heart.bmj.com/supplemental

References

- 1.ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing Am J Respir Care Med. 2003;167:211–277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis C. Rehabilitation of patients with coronary artery disease. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart disease, a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 19921382

- 3.Brooks G A. Anaerobic threshold: review of the concept and directions for future research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 19851722–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonton C A, Higginbotham M B, Cobb F R. The ventilatory threshold: quantitative analysis of reproducibility and relation to arterial lactate concentrations in normal subjects and in patients in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 198862100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumura N, Nishijima H, Kojima S et a l. Determination of anaerobic threshold for assessment of functional state in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 198368360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuberg G W, Friedman S H, Weiss M B.et al Cardiopulmonary exercise testing. The clinical value of gas exchange data. Arch Intern Med 19881482221–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell J H, Blomqvist G. Maximal oxygen uptake. N Engl J Med 19712841018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchfuhrer M J, Hansen J E, Robinson T E.et al Optimizing the exercise protocol for cardiopulmonary assessment. J Appl Physiol 1983551558–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naughton J, Sevelius G, Balke B. Physiological responses of normal and pathologic subjects to a modified work capacity test. J Sports Med 196331201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright D J, Khan K M, Gossage E M.et al Assessment of a low‐intensity cardiac rehabilitation programme using the six‐minute walk test. Clin Rehabil 200115119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis J A. Anaerobic threshold: review of the concept and directions for future research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1985176–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings G L, Esler M D. Circulatory regulation at rest and exercise and the functional assessment of patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 199081II5–NaN13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasserman K, Hansen J E, Sue D Y.et alPrinciples of exercise testing and interpretation. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1987

- 14.Beaver W L, Wasserman K, Whipp B J. A new method for detecting the anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol 1986602020–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh M P, Gardner R M, Adams T D.et al “Anaerobic threshold”: problems of determination and validation. J Appl Physiol 1983551178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons R J, Balady G J, Bricker J T.et al ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). Circulation 20021061883–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons R J, Balady G J, Beasley J W.et al ACC/AHA guidelines for exercise testing: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). J Am Coll Cardiol 199730260–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rochmis P, Blackburn H. Exercise tests: a survey of procedures, safety, and litigation experience in approximately 170,000 tests. JAMA 19712171061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pina I L, Apstein C S, Balady G J.et al Exercise and heart failure: a statement from the American Heart Association Committee on exercise, rehabilitation, and prevention. Circulation 20031071210–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy H K, Weber K T, Janicki J S.et al Hemodynamic, ventilatory and metabolic effects of light isometric exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 198812353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington D, Anker S D, Chua T P.et al Skeletal muscle function and its relation to exercise tolerance in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997301758–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright D J, Tan L B. The role of exercise testing in the evaluation and management of heart failure. Postgrad Med J 199975453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghali J K, Cooper R, Ford E. Trends in hospitalisation rates for heart failure in the US 1973–86. Arch Intern Med 1990150769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colucci W S. In vivo studies of myocardial beta‐adrenergic receptor pharmacology in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 199082I44–I51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler J, Chomsky D B, Wilson J R. Pulmonary hypertension and exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999341802–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pina I L, Apstein C S, Balady G J.et al Exercise and heart failure: a statement from the American Heart Association Committee on exercise, rehabilitation, and prevention. Circulation 20031071210–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMurray J, Pfeffer M A. New therapeutic options in congestive heart failure: part I. Circulation 20021052099–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMurray J, Pfeffer M A. New therapeutic options in congestive heart failure: part II. Circulation 20021052223–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham W T, Fisher W G, Smith A L.et al Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 20023461845–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beniaminovitz A, Mancini D M. The role of exercise‐based prognasticating algorithms in the selection of patients for heart transplantation. Curr Opin Cardiol 19994114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corra U, Mezzani A, Bosimini E.et al Cardiopulmpnary exercise testing and prognosis in chronic heart failure. Chest 2004126942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mancini D M, Eisen H, Kussmaul W.et al Value of peak oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation 199183778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costanzo M R, Augustine S, Bourge R.et al Selection and treatment of candidates for heart transplantation. Circulation 1995923595–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stelken A M, Younis L T, Jennison S H.et al Prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing using percent achieved of predicted peak oxygen uptake for patients with ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 199627345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aaronson K D, Mancini D M. Is percentage of predicted maximal exercise oxygen consumption a better predictor of survival than peak exercise oxygen consumption for patients with severe heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 199514981–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osman A F, Mehra M R, Lavie C J.et al The incremental prognostic importance of body fat adjusted peak oxygen consumption in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000362126–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen‐Solal A, Zannad F, Kayanakis J G.et al Multicenter determination of the oxygen uptake and ventilatory threshold. Eur Heart J 1991121055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opasich C, Pinna G D, Bobbio M.et al Peak oxygen consumption in chronic heart failure: toward efficient use in the individual patient. J Am Coll Cardiol 199831766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chua T P, Ponikowski P, Harrington D.et al Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of the ventilatory response to exercise in CHF. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997291585–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleber F X, Vietzke G, Wernecke K D.et al Impairment of ventilatory efficiency in heart failure: prognostic impact. Circulation 20001012803–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacGowan G A, Janosko K, Cecchetti A.et al Exercise related ventilatory abnormalities and survival in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1997791264–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robbins M, Francis G, Pashkow F J.et al Ventilatory and heart rate response to exercise: better predictors of heart failure mortality than peak oxygen consumption. Circulation 19991002411–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corra U, Mezzani A, Bosimini E.et al Ventilatory response to exercise improves risk stratification in chronic heart failure patients with intermediate functional capacity. Am Heart J143418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mezzani A, Corra U, Baroffio C.et al Habitual activities and peak aerobic capacity in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction: use of a new physical activity scoring system. Chest 20001171291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mezzani A, Corra U, Bosimini E.et al Contribution of peak respiratory exchange ratio to peak VO2 prognostic reliability in patients with chronic heart failure and severely reduced exercise capacity. Am Heart J 20031451102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Task Force of the Italian Working Group on Cardiac Rehabilitation and Prevention (Gruppo Italiano di Cardiologia Riabilitativa e Prevenzione, GICR); Working Group on Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology of the European Society of Cardiology, Piepoli MF, et al. Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction: recommendations for performance and interpretation Part II: How to perform cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 200613300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]