Abstract

Emotional arousal and the affective content of events influence memory. These effects shift with age such that older people find negative information less arousing and remember proportionately more positive events compared to the young. The emotional enhancement of memory is mediated by medial temporal lobe limbic structures and the prefrontal cortex, which are both affected by sex hormones. We examined whether hormone use (estrogen or estrogen and progesterone) in older women modulated perceptions of valence and arousal, and subsequent memory for emotional images or stories. Their performance was compared to younger women. Hormone use in older women resulted in higher arousal for negative images and stories but memory was not affected. We hypothesize that estrogen modifies the influence of the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex on emotion, but that age-related changes in the hippocampus prevent the enhancement of emotional memory in older women.

Keywords: emotion, arousal, estrogen, hormone therapy, memory

1. Introduction

People remember emotional events better than neutral information (Bradley et al., 1992; Cahill and McGaugh, 1995). This has been called the “emotional enhancement” of memory and is dependent on the arousing nature of events as well as their affective content, such as whether an event is negative or positive. The neural circuit for emotional enhancement includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Cahill and McGaugh, 1998; LaBar and Cabeza, 2006) as shown by lesion and neuroimaging studies in humans (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003; Hamann et al., 1999), nonhuman primates (Meunier et al., 1999) and rodent models (Gale et al., 2004). Arousal and amygdala activity predict subsequent memory for emotional events (Canli et al., 2000; Hamann et al., 1999). In addition, the amygdala can be modulated with beta-adrenergic antagonists and adrenaline (Cahill et al., 1998), both of which induce variations in arousal.

Estrogen receptors are located in the amygdala and hippocampus of humans (Osterlund et al., 2000a) and non-human primates (Osterlund et al., 2000b), as well as rodents (McEwen and Alves, 1999). Chronic estrogen treatment in ovariectomized mice increases fear and anxiety-related behaviors as measured by the open field test, dark-light transition test, elevated plus-maze, and conditioned fear (Morgan and Pfaff, 2001). Additionally, increased fear behavior after chronic estrogen treatment is linked to protein changes in the central amygdale (Jasnow et al., 2006). However, not all studies agree. Systemic and amygdala injections of estrogen decrease anxiety, fear, and pain behaviors in ovariectomized mice (Frye and Walf, 2004). In younger women, perception of fearful faces is worse in the pre-ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen is high, than during menstruation, when estrogen is low (Pearson and Lewis, 2005). Additionally, amygdala activity induced by emotional images is lower at the high estrogen phase (as compared to neutral images) than the low estrogen phase of the menstrual cycle (Goldstein et al., 2005). The exact mechanisms remain unclear; however, these data suggest an estrogen-mediated modification of emotional enhancement via the amygdala.

Aging modifies emotions and memory: older adults experience less negative affect (Mroczek and Kolarz, 1998) and, on average, remember more positive material and proportionately less negative material than younger adults (Charles et al., 2003; Leigland et al., 2004). Both psychological and biological theories address these age-related changes in emotion and memory. Socioemotional Selectivity, a theory from social psychology, suggests that older people focus on positive emotions because they perceive time as limited and want to optimize emotional satisfaction (Carstensen et al., 1999). Thus they attend less to negative stimuli (Mather and Carstensen, 2003) and show greater amygdala activation to positive versus negative stimuli (Mather et al., 2004). In addition, they show diminished cardiovascular response when discussing emotional conflicts (Levenson et al., 1994), viewing sad or amusing films (Tsai et al., 2000), and have diminished heart rate deceleration and corrugators EMG response to images in all valence categories (negative, neutral, and positive) as compared to young (Smith et al., 2005).

Age-related neurobiological changes may underlie age differences in emotional responses and brain activity in aging. Certainly, there are atrophic changes at the source of the emotional memory system even in healthy elderly without signs of neurodegenerative disease (Mu et al., 1999). For example, the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex have volume losses of approximately 8–12%, 13%, and 14–15% respectively, across the 30–80 year old age range (Allen et al., 2005). However, women taking estrogen have larger right hippocampal volumes (Eberling et al., 2003; Lord et al., 2006) and more PET activity in the right and left orbital frontal cortex than women not taking estrogen (Eberling et al., 2004). Women using estrogen also have higher white matter density in the frontal, prefrontal, and temporal regions, higher grey matter density in the medial temporal lobe, and smaller CSF volumes than women not using estrogen (Erickson et al., 2005). Recent work corroborates this- women taking estrogen have smaller ventricles and more white matter compared to women not taking estrogen (Ha et al., 2007). These studies of estrogen's neuroprotective effects involve women on very long-term estrogen therapy, often from the time of menopause to the late decades of life. This evidence suggests a neuroprotective role for estrogen; however, conflicting results suggest no structural brain effects of hormone use (Low et al., 2006), including ventricle size (Schmidt et al., 1996). Additionally, in a study with age-matched groups, shorter durations of hormone use (10 years or less) spares more prefrontal tissue than longer durations (Erickson et al., 2007).

In our study we examined whether hormone use in elderly women modified arousal and memory. Here young women aged 24–40 on no hormone therapy and older women aged 65 – 85 either using hormone therapy or not participated in the study. Women rated the valence and arousal of emotional images (Lang et al., 1999) and, in a second measure, images illustrating a story that had neutral content in the beginning and end, but negative content in the middle (Heuer and Reisberg, 1990). Subsequently the women were tested for recognition of the images and story. We examined whether hormone use differentially affected perceptions of valence and arousal, or memory for emotional images and stories.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Women aged 65–85 and 24–40 (YOUNG) participated in the study (see Table 1). The older women were either using estrogen therapy with or without progesterone (HT), or were not (NONE). Women were recruited on hormone therapies prescribed by their personal physicians and remained on their hormone regimen during the study. They were reimbursed for hormone medications used during the study period. Inclusion criteria required that the older women were healthy, had not menstruated within one year, and were using chronic hormone therapy (mean = 24.0 yrs.; range = 4–52 yrs.). For most HT women, hormone therapy extended from menopause to old age. Approximately 62% of the older women using hormone therapy were on estrogen-alone and the rest were on estrogen and progesterone. NONE women were healthy and were not currently using any type of hormone therapy. YOUNG women were not using hormone therapy or hormonal contraceptives. Information regarding menstrual cycle status at the time of testing was not collected; however, young women had to have regular (25–35 day) cycles. The young women were included in this study to highlight age effects on emotion. Other criteria for all participants included fluency in English and adequate hearing and vision (with correction if necessary) to view computer tasks. Medical histories were obtained via phone interview and confirmed in person. Exclusion criteria included: smoking or having quit less than one month from the study date; drinking more than 3 alcoholic beverages per day; psychiatric conditions (history of schizophrenia, mood, or anxiety disorders); significant medical problems (e.g. uncontrolled hypertension); current use of medications likely to affect cognition (e.g. anti-anxiety agents such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors); and neurological problems, such as stroke, seizures or head trauma (unconscious longer than 15 minutes or requiring hospitalization); and, for the older women only, depression (Geriatric Depression Scale; GDS >10;Yesavage et al., 1983) or possible dementia (Mini-Mental Status Examination; MMSE <26; Folstein et al., 1975).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| HT (n = 45) | NONE (n = 26) | YOUNG (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.0 (65–84) | 72.7 (65–85) | 29.4 (24–40) |

| Education (years) | 15.6 (12–22) | 15.5 (12–23) | 17.0 (12–20) |

| WAIS-R Vocabularya | 53.2 (32–67) | 53.7 (37–67) | 54.5 (40–65) |

| MMSE | 28.5 (26–30) | 28.7 (26–30) | NAb |

| GDS | 3.7 (0–10) | 3.2 (0–9) | NAb |

Note: Range is shown in parentheses.

Raw scores.

Not measured in younger subjects.

HT and NONE groups were matched for age (t (69) = 0.255, p = 0.800) and education (t (69) = 0.190, p = 0.850). YOUNG women had more formal education than HT and NONE women (Bonferroni corrected ps < 0.050); however, all groups were matched for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Vocabulary Test-Revised Vocabulary subtest (WAIS-R; Wechsler, 1981); F (2, 93) = 0.186, p = 0.831). The WAIS-R provides a standardized approximation of functional intelligence and was used as a surrogate, additional measure of education because years of schooling in the elderly may not reflect intellectual ability due to changes in education requirements over the last eight decades as well as lifelong education. One participant from the NONE group was excluded because she was unable to perform tasks correctly (final n = 26). Participants were recruited through advertisements, invitation letters sent to a database of previous study participants, the Oregon Health & Science University patient database, or a database of DMV records. All participants provided written informed consent and were paid for their time and involvement in the study.

2.2 Procedures

2.2.1 Picture Ratings and Recognition

Participants viewed 90 images selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., 1999). The images were divided equally among three a priori valence categories: negative, neutral, and positive. The images chosen were based on the published norms for valence ratings. The average normal valence ratings were 2.73 for negative (range: 1.56–3.71), 5.00 for neutral (range: 3.90–5.99), and 7.57 for positive (range: 7.02–8.34) images. Negative images had lower ratings than neutral, which had lower ratings than positive (F (2, 87) = 591, p < 0.001; Bonferroni corrected ps < 0.001). The average normal arousal ratings for the images were 4.99 for negative (range: 4.06–6.00), 4.79 for neutral (range: 3.31–6.97), and 5.09 for positive (range: 4.15–6.28). The negative, neutral, and positive categories had equivalent arousal ratings (F (2, 87) = 1.24, p = 0.293). All three valence categories were matched for content (i.e. there were equal numbers people, animals, or food in each category). Images appeared for 2 seconds after which they were rated on a 9-point scale for valence (1 = negative, 5 = neutral, 9 = positive) and arousal (1 = calming, 5 = neutral, 9 = exciting). Order of presentation was randomized with respect to valence. Mean valence and arousal ratings were calculated by taking the average subject ratings across each section. Participants were not told that they would be asked to remember the images later.

After a one or two week retention interval, (meanold = 7.3 days, rangeold = 7–13 days; meanyoung = 14.3 days, rangeyoung = 14–18 days), participants performed a recognition test. The longer retention interval for the young subjects was an effort to match retention in the old and young in order to examine age and hormone effects on valence and arousal without the confound of differences in overall memory performance among groups. During the yes/no recognition test participants viewed 180 images comprised of the 90 images they rated previously and 90 novel images with percent correct as the dependent variable. The 90 novel images were matched for a priori valence, arousal, and content. Order of picture presentation was randomized with respect to target/novel status and valence.

2.2.2 Story Ratings and Recognition

The story task used in this study has been used extensively by others (Cahill et al., 1995), who have established that people remember emotionally arousing material better than neutral or non-emotional material (Cahill et al., 1995; Heuer et al., 1990) and that amygdala activity is associated with this memory enhancement (Cahill et al., 2006; Canli et al., 2000). Participants viewed 11 slides accompanied by an auditory narration of a short story. The story was composed of three sections: first, a relatively non-emotional (neutral) section (slides 1 – 4); second, an emotionally arousing (negative) section (slides 5 – 8); and third, another non-emotional (neutral) section (slides 9 – 11). The first section depicts a mother and son going on an outing, the second section portrays the boy being struck by a car and taken to the hospital, and the third section shows the mother after the incident when the crisis has been resolved.

Participants viewed each slide for 15 seconds. Participants rated the slide and narration for valence and arousal. Ratings were made on a 9-point scale, with low values indicating negative valence and lower arousal. Mean valence and arousal ratings were calculated by taking the average subject ratings across each section. Participants were not told that they would be asked to remember the slides and story later. At a second visit, with the same retention intervals as for the image task, participants answered 76 multiple-choice questions about the story and slides (5 – 9 questions per slide). We calculated recognition as the percentage of questions participants answered correctly out of the total questions possible. Recognition was chosen over free recall because free recall can lead to ambiguous answers. This is particularly true with numerous complex visual stimuli that can be difficult to accurately describe and that have no normative data from the elderly on free recall on this task.

2.3 Data Analyses

One-way repeated measures ANOVA (SPSS version 14.0) was used to compare treatment groups across valence categories, with valence category as the repeated measure. Tukey HSD post hoc corrections or paired t tests with Bonferroni corrections were used where appropriate to examine main effects and interactions. Simple main effects were performed on interactions. Significance level was set at 0.05. Older women using estrogen alone or estrogen with progesterone were analyzed separately. They did not statistically differ on any measure and were thus reported together as the HT group.

3. Results

3.1 Images

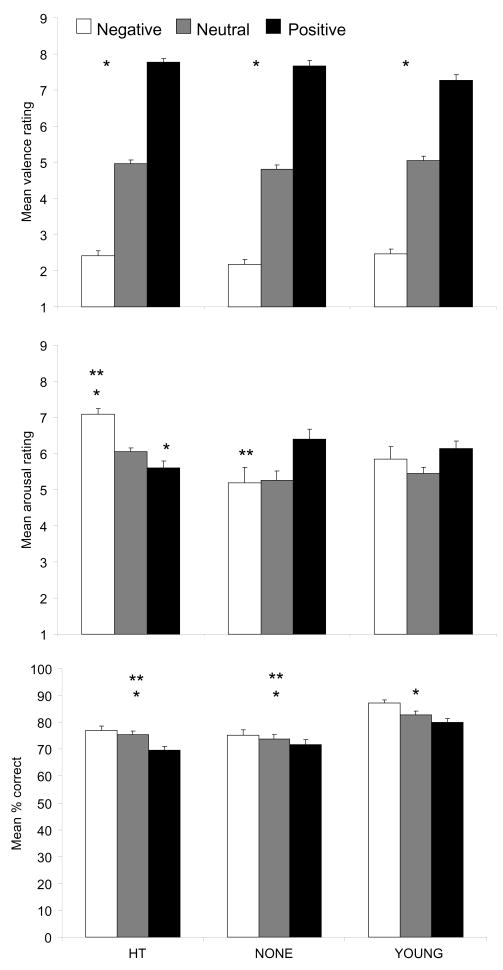

3.1.1 Valence ratings

Valence ratings of the images differed by valence category (neg vs. neu vs. pos: F (2, 186) = 1230, p < 0.001) and were not affected by group status (YOUNG vs. HT vs. NONE: F (2, 93) = 0.929, p = 0.399; Figure 1a). Participants rated negative images as more negative than neutral and positive images and rated positive images as more positive than neutral or negative images (ts (95) < −27, ps < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected), as expected by the design of the stimuli.

Figure 1.

Effects of estrogen on perception of images. Top: Valence ratings did not differ across groups (* = neg< neu< pos; ps < 0.001). Middle: HT women rated negative images as more arousing than positive images (t (44) = 5.79, p < 0.001); NONE women rated positive images as more arousing than negative (t (25) = −2.48, p = 0.06, Bonferroni corrected). HT women rated negative images more arousing (F (2, 93) = 12.9, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc p < 0.001) and positive images less arousing than NONE women (F (2, 93) = 3.60, p = 0.031; Tukey post hoc p = 0.032), suggesting that estrogen treatment enhances sensitivity to negative material. YOUNG women did not differ in arousal ratings across valence categories. * = different from NONE for that valence category; ** = different from positive valence within the group. Bottom: HT (t (44) = 6.13, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected), NONE (t (25) = 2.42, p = 0.069, Bonferroni corrected), and YOUNG (t (24) = 5.98, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected) women correctly recognized more negative than positive images. YOUNG women had better memory for all valences (Fs (2, 93) > 8.40, ps < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.008). Retention was tested after one week for the older women and two weeks for the younger women. * = negative different than positive within the group; ** = group different than young.

3.1.2 Arousal ratings

We used normative arousal ratings (Lang et al., 1999) to create stimuli sets matched for mean arousal levels across valence categories. This allowed us to disentangle group differences in valence and arousal effects. Arousal ratings of the images differed by group (F (2, 93) = 4.22, p = 0.018) and valence category (F (2, 186) = 5.44, p = 0.005). Both of these effects were modified by a significant group by valence category interaction (F (4, 186) = 14.2, p < 0.001; Figure 1b). Younger women’s arousal ratings were similar across the valence categories (F (2, 48) = 2.40, p = 0.102). However, arousal ratings differed across valence categories for both groups of older women (HT: F (2, 88) = 31.5, p < 0.001; NONE: F (2, 50) = 7.15, p = 0.002). HT women rated negative images as more arousing than neutral or positive images (ts (44) > 2.50, ps < 0.001). Conversely, NONE women rated positive images as more arousing than neutral images (t (25) = −4.67, p < 0.001) with a trend towards rating positive images more arousing than negative (t (25) = −2.48, p = 0.06, Bonferroni corrected). NONE women also rated positive images as more arousing than did the HT women (F (2, 93) = 3.60, p = 0.031; Tukey post hoc p = 0.032), while the HT women rated negative images as more arousing than did the NONE women (F (2, 93) = 12.9, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc p < 0.001).

3.1.3 Recognition

Recognition for images differed by valence (F (2, 186) = 34.9, p < 0.001) and group (F (2, 93) = 11.6, p < 0.001), and was affected by a significant valence by group interaction (F (2, 186) = 2.86, p = 0.025; Figure 1c). YOUNG women recognized more images than both groups of older women for each valence category (Fs (2, 93) > 8.40, ps < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.008). Emotional content shaped memory for all three groups of women (HT: F (2, 88) = 28.3, p < 0.001; NONE: F (2, 50) = 2.92, p = 0.063–trend; YOUNG: F (2, 48) = 17.0, p < 0.001). HT (t (44) = 6.13, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected), NONE (t (25) = 2.42, p = 0.069, Bonferroni corrected), and YOUNG (t (24) = 5.98, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected) women all recognized more negative than positive images. HT women also recognized more neutral than positive images (t (44) = 5.80, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected), and YOUNG women recognized more negative than neutral images (t (24) = 3.87, p = 0.003, Bonferroni corrected).

3.2 Story

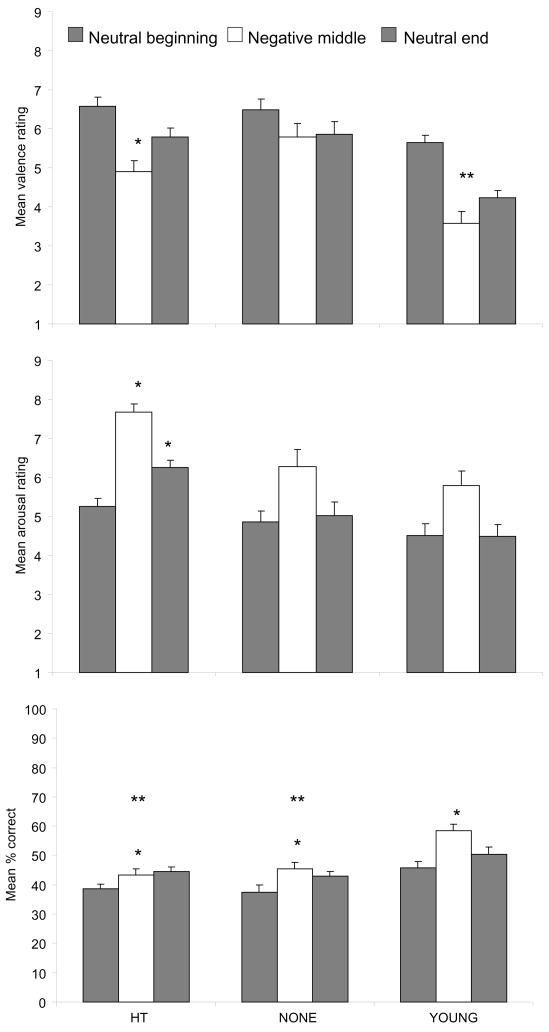

3.2.1 Valence ratings

Valence ratings differed across story sections (F (2, 186) = 32.6, p < 0.001; Figure 2a) and group (F (2, 93) = 13.3, p < 0.001). These main effects were modified by a group by section interaction (F (4, 186) = 2.50, p = 0.044). Valence ratings differed across story sections for both HT (F (2, 88) = 15.8, p < 0.001) and YOUNG (F (2, 48) = 31.3, p < 0.001) women. Both groups perceived the middle section more negatively than the beginning (HT: t (44) = 5.40, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected; YOUNG: t (24) = 6.76, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected); HT women also perceived the middle more negatively than the end (t (44) = −2.68, p = 0.030, Bonferroni corrected). NONE rated the valence of all three sections similarly.

Figure 2.

Effects of estrogen on perception of the story. Top: HT (t (44) = 5.40, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected) and YOUNG (t (24) = 6.76, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected) women rated the middle of the story more negatively than the beginning (ps < 0.001), and HT women rated the middle more negatively than the end ((t (44) = −2.68, p = 0.030, Bonferroni corrected). NONE women rated the valence of all three sections similarly. * = middle different from beginning and end within group; ** = middle different from beginning within group. Middle: HT women rated the middle and ending sections of the story as more arousing than did the YOUNG and NONE women (Fs (2, 93) > 10.6, ps < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.007). * = different from NONE and YOUNG for that section. Bottom: All groups remembered the middle and end sections of the story better than the beginning (F (2, 186) = 14.4, p < 0.001; post hoc ps < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected). YOUNG women had better memory for all sections overall (F (2, 93) = 13.3, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.001), even though retention was tested after one week for the older women and two weeks for the younger women in an effort to equate memory between the groups. First gray bar (neutral) = beginning section of story; middle empty bar (negative) = middle section; second gray bar (neutral) = end section. * = middle and end sections different from beginning section within the group; ** = group different than young.

3.2.2 Arousal ratings

There were main effects of group (F (2, 186) = 46.1, p < 0.001) and story section (F (2, 93) = 13.8, p < 0.001) on arousal, as well as a significant group by section interaction (F (4, 186) = 2.56, p = 0.040; Figure 2b). Arousal ratings differed across story sections in all groups (Fs > 8.18, ps < 0.002). Everyone found the middle section more arousing than the beginning (ts < −2.88; ps < 0.025, Bonferroni corrected) or ending (ts > 4.31, ps < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected). However, HT women showed less recovery than the NONE or YOUNG women from the negative, emotionally arousing middle section of the story. Only the HT women also found the ending to be more arousing than the beginning (t (44) = −3.89, p < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected). Additionally, HT women found the middle (F (2, 93) = 10.7, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.007) and ending (F (2, 93) = 12.9, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.004) sections more arousing than did the NONE and YOUNG women.

3.2.3 Recognition

Finally, younger women remembered more of the story than both groups of older women (F (2, 93) = 13.3, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc ps < 0.001; Figure 2c), and all groups remembered the middle and end sections of the story better than the beginning (F (2, 186) = 14.4, p < 0.001; post hoc ps < 0.003, Bonferroni corrected).

4. Discussion

Older women had enhanced subjective arousal to positive stimuli and lower subjective arousal to negative stimuli. However, we found that hormone therapy modified this response. Hormone therapy enhanced arousal to negative material in two tasks involving emotional perception (images and story). HT women rated negative images as more arousing than positive images, and gave negative images higher arousal ratings than did the NONE or YOUNG women. In addition, HT women rated the negative, middle section of the story as more arousing than did the NONE and YOUNG women, and showed less recovery from the arousing negative images than the NONE and YOUNG women. However, greater arousal for positive or negative stimuli did not result in better memory for those stimuli. All three groups of women recognized negative images better than positive images and remembered the negative information from the middle section of the story better than the neutral information in the beginning. In fact, HT women, who showed the highest arousal to the negative material in the story, did not remember that material any better than the NONE or YOUNG women. Thus, higher arousal did not necessarily lead to better memory, suggesting that hormones modify the arousal system, but not memory, in older women. We suggest that the effects of hormone therapy are due to estrogen because performance did not differ between those on estrogen and those on a combined estrogen and progesterone regimen. However, larger groups of HT women will be needed to solidify that conclusion.

Both neurobiological and a cognitive/social psychological perspectives are relevant to these findings. One neurobiological explanation is that estrogen affects the amygdala, such that estrogen use increases and sustains amygdala reactivity to negative emotional material in older women. The amygdala is especially responsive to negative emotional material, (Lane et al., 1997; Morris et al., 1996) and, as a site for estrogen activity (McEwen et al., 1999; Osterlund et al., 2000a; Osterlund et al., 2000b), may enhance amygdala activity in older women who otherwise are hormone deprived. This is in contrast to young women, where amygdala activity to negative images was lower at the high estrogen phase than the low estrogen phase of the menstrual cycle (Goldstein et al., 2005). The differences between old and young women may be due to the effects of fluctuations, as opposed to chronic deprivation or chronic estrogen, or due to an interaction between an aging brain and sex hormones. An alternative neurobiological explanation is that estrogen modifies the interaction between prefrontal regions and the amygdala, such that women using hormones have less prefrontal activity, which permits sustained amygdala reactivity. Neuroimaging studies in young adults (Kim et al., 2003) and electrophysiology studies in rodents and felines (Quirk et al., 2003) suggest an inverse relationship between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex activity. Older adults show more activity in prefrontal regions and less activity in the amygdala during the processing of emotional faces, as compared to young adults (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003; Tessitore et al., 2005). The greater activity in prefrontal cortex in the elderly to a variety of stimuli has been interpreted as compensatory (Cabeza et al., 2002), but it may amplify inhibition of the amygdala and thus decrease arousal to negative stimuli in aging. This could explain the lower arousal to negative material and higher arousal to positive material seen in the NONE women in this study. We propose that estrogen reverses this effect, since HT women demonstrated the opposite pattern. Finally, functional neuroimaging would be a preferred way to assess brain function; however, the measures used here have been used in many other lesion (Adolphs et al., 1997; Cahill et al., 1995; Cahill et al., 1994) and functional neuroimaging studies (Cahill et al., 2004; Canli et al., 2002; Lane et al., 1997; Liberzon et al., 2000), which suggest the amygdala is critical for the perception of the emotional aspects of these stimuli. Furthermore, studies using IAPS images have correlated amygdala activity with arousal (Canli et al., 2000) and memory (Hamann et al., 1999). It is because of this prior work that we suggested the neurobiological models for the hormone effects that we found.

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) can be related to our proposed neurobiological mechanism. SST suggests that awareness of limited time leads older adults to prioritize positive emotional goals (Charles et al., 2003; Mather et al., 2003; Carstensen et al., 1999). This prioritization may be due to cognitive control mechanisms, since older adults do not show a positivity bias when they are distracted while viewing emotional images or when they have low scores of cognitive control (Mather and Knight, 2005). This higher cognitive control may contribute (or be due to) to the increased prefrontal activity seen in older adults (Cabeza et al., 2002), which, in turn, relates to amygdala inhibition (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003; Tessitore et al., 2005; Urry et al., 2006). We propose that age-related changes in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala may accentuate or complement the “positivity effect” and cognitive control found in older adults(Carstensen et al., 1999), but that estrogen sustains brain reactivity to negatively arousing stimuli either through increased amygdala response or lowered prefrontal inhibition.

Other fields also offer some interesting perspectives on our results. The positive bias seen in older women without hormones may be an adaptive shift. The grandmother hypothesis posits that menopause is an advantageous adaptation to increase species survival (Hawkes et al., 1998) and longevity (Hawkes, 2003). Since post-menopausal women cannot produce anymore of their own children, they help care for (e.g. provide food for) the children of their daughters and nieces, which is hypothesized to improve the survival of those children (Hawkes et al., 1998; Hawkes, 2003). In relation to our current work, the loss of estrogen that accompanies menopause would increase arousal to positive entities in women’s lives (e.g. their grandchildren), and increase the likelihood that they would want to enhance their survival. Another advantage for the positive emotional shift in the elderly relates to health. Negative emotions have been associated with increased severity of some health problems (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002) et al., 2002), particularly those that are common among he elderly (e.g. depression, cardiovascular disease, inflammation-related diseases). Thus, the positive bias in women without estrogen may have a positive impact on their health. Therefore, the higher hormone levels that lead to more arousal to negative material may not be evolutionarily adaptive or psychologically beneficial in older women.

Hormone use affected subjective emotional arousal in the older women; however, it did not affect memory (percent correct recognition) for any valence category for either the images or the story. HT, NONE and YOUNG women all remembered negative images better than positive images, and remembered the negative part of the story better than the neutral beginning. Finding that memory did not correspond to emotional arousal in our older women is actually quite surprising from a neurobiological viewpoint. Like the amygdala, the hippocampus is a site of estrogen activity (McEwen et al., 1999; Osterlund et al., 2000a; Osterlund et al., 2000b). Both the amygdala and hippocampus are critical to emotional memory (Cahill et al., 1998; LaBar et al., 2006), and evidence suggests that the amygdala influences both encoding and consolidation of memory in the hippocampus (for review see (Phelps, 2004). Therefore, a hypothesis to be tested in futures studies is that the connection between the amygdala and hippocampus is modified in aging, such that estrogen may restore function in the amygdala, but not the hippocampus, in older women.

This data adds to a number of other studies of hormone effects on memory. This has become a complex and contentious issue. While epidemiological studies suggest that hormone therapy decreases the risk for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD; LeBlanc et al., 2001; Yaffe et al., 1998), neither randomized, placebo-controlled studies (Henderson et al., 2000; Mulnard et al., 2000) nor the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study confirmed this finding (Espeland et al., 2004; Shumaker et al., 2004). Second, direct studies of estrogen’s effects on memory in healthy older women have varying results, possibly due to the somewhat differing subject populations and measures. Placebo controlled trials of women with surgically induced menopause found that estrogen treatment enhanced verbal memory performance, as measured by the digit span task and paragraph recall, (Sherwin, 1988), and lack of estrogen impaired performance on word-pair associations (Phillips and Sherwin, 1992). However, estrogen treatment in the perimenopausal period did not enhance memory (LeBlanc et al., 2007). In older post-mensopausal women, some studies show that estrogen use enhances performance on tests of verbal (Kampen and Sherwin, 1994) and visual or spatial memory (Duka et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2001); however, several others do not (File et al., 2002; Grigorova and Sherwin, 2006; Polo-Kantola et al., 1998; Schiff et al., 2005). Finally, there are no other studies to date that examine hormone effects on memory for emotional stimuli, particularly for images in the IAPS. Thus, the effects of estrogen on memory may be influenced by several factors, including disease state, age, stimulus type. However, it may not be influenced by emotional arousal, as our results suggest a disconnect between emotional enhancement and memory.

We tried to equate memory between the old and young women by extending the retention interval for the young age group, but they still outperformed the older women. However, since the two groups of older women performed similarly, we do not believe it limits our conclusions. The main findings were the difference in arousal between the older women using hormones, and that this did not affect memory. Additionally, the attempt to equate memory was to insure that differential memory performance did not preclude interpretation of differential memory for each emotion condition among groups. However, all three groups showed a similar pattern of emotion on memory, that is, better memory for negative images and parts of the story. We used only recognition tasks to assess memory. Other studies have used recall and recognition to assess memory for the story task (Cahill et al., 1994; Heuer et al., 1990). Recall and recognition are not the same processes; therefore, our current study cannot determine whether we would obtain the same results for recall as we did for recognition.

We acknowledge that the cross-sectional design and the variety of the estrogen therapies preclude a full understanding of the effects of estrogen therapy on emotion in aging. Similar valence ratings and memory performance in both groups of older women on two different tasks suggest that the so-called “healthy user bias” would not explain our findings. Additionally, these results are from women on long-term hormone therapy, which precludes a randomized, placebo-controlled design. We do not know if similar effects would occur with brief use of hormones in older women. We analyzed duration of hormone use and mean negative arousal in older women and did not find a significant correlation, suggesting that duration does not affect arousal for these women. However, we are not suggesting that duration is not important. The majority of women in the study used HT for many years, so our range may not be large enough. Nor can our results be due to the a priori grouping of IAPS images based on normative ratings from young adults because he older women did not differ from younger women on their valence ratings, suggesting that age did not affect how women categorize emotions. Nor would such age effects explain the differences in arousal found between the hormone groups who are both older.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01 AG12611 & PHS Grant 5 M01 RR000334. The authors thank Phyllis Carello and Karla Schilling for assistance with data collection, and Larry Cahill for generously supplying us the story stimuli.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Adolphs R, Cahill L, Schul R, Babinsky R. Impaired declarative memory for emotional material following bilateral amygdala damage in humans. Learn Mem. 1997;4:291–300. doi: 10.1101/lm.4.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JS, Bruss J, Brown CK, Damasio H. Normal neuroanatomical variation due to age: The major lobes and a parcellation of the temporal region. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1245–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M, Greenwald MK, Petry MC, Lang P. Remembering pictures: pleasure and arousal in memory. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1992;18:379–390. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Locantore JK, McIntosh AR. Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1394–1402. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, McGaugh JL. Mechanisms of emotional arousal and lasting declarative memory. Trends in Neuroscience. 1998;21:294–299. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, McGaugh JL. A novel demonstration of enhanced memory associated with emotional arousal. Conscious Cogn. 1995;4:410–421. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Prins B, Weber M, McGaugh JL. Beta-adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events. Nature. 1994;371:702–704. doi: 10.1038/371702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Uncapher M, Kilpatrick L, Alkire MT, Turner J. Sex-related hemispheric lateralization of amygdala function in emotionally influenced memory: an FMRI investigation. Learn Mem. 2004;11:261–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.70504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Uncapher M, Kilpatrick L, Alkire MT, Turner J. Sex-related hemispheric lateralization of amygdala function in emotionally influenced memory: an FMRI investigation. Learn Mem. 2006;11:261–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.70504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Gabrieli JD. Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:10789–10794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162356599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Zhao Z, Brewer J, Gabrieli JD, Cahill L. Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with later memory for individual emotional experience. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: the forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duka T, Tasker R, McGowan JF. The effects of 3-week estrogen hormone replacement on cognition in elderly healthy females. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;149:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s002139900324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberling JL, Wu C, Haan MN, Mungas D, Buonocore M, Jagust WJ. Preliminary evidence that estrogen protects against age-related hippocampal atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:725–732. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberling JL, Wu C, Tong-Turnbeaugh R, Jagust WJ. Estrogen- and tamoxifen-associated effects on brain structure and function. Neuroimage. 2004;21:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Colcombe SJ, Elavsky S, McAuley E, Korol DL, Scalf PE, Kramer AF. Interactive effects of fitness and hormone treatment on brain health in postmenopausal women. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Colcombe SJ, Raz N, Korol DL, Scalf P, Webb A, Cohen NJ, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Selective sparing of brain tissue in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, Hsia J, Margolis KL, Hogan PE, Wallace R, Dailey M, Freeman R, Hays J. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2959–2968. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Heard JE, Rymer J. Trough oestradiol levels associated with cognitive impairment in post-menopausal women after 10 years of oestradiol implants. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;161:107–112. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: A practical method of grading the cognitive status of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Walf AA. Estrogen and/or progesterone administered systemically or to the amygdala can have anxiety-, fear-, and pain-reducing effects in ovariectomized rats. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:306–313. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Godsil BP, Mitchell S, Nozawa T, Sage JR, Wiltgen B, Fanselow MS. Role of basolateral amygdala in the storeage of fear memories across the adult lifetime of rats. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:3810–3815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4100-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, Makris N. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:9309–9316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorova M, Sherwin BB. No differences in performance on test of working memory and executive functioning between healthy elderly postmenopausal women using or not using hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2006;9:181–194. doi: 10.1080/13697130600727107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Gur RC, Perkins AC, Schroeder L, Turner T, Turetsky BI, Chan RM, Loughead JW, Alsop DC, Maldjian J, Gur RE. Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face processing. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha DM, Xu J, Janowsky JS. Preliminary evidence that long-term estrogen use reduces white matter loss in aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann SB, Ely TD, Grafton ST, Kilts CD. Amygdala activity related to enhanced memory for pleasant and aversive stimuli. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:289–293. doi: 10.1038/6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K. Grandmothers and the evolution of human longevity. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15:380–400. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, O'Connell JF, Jones NG, Alvarez H, Charnov EL. Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1336–1339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson VW, Paganini-Hill A, Miller BL, Elble RJ, Reyes PF, Shoupe D, McCleary CA, Klein RA, Hake AM, Farlow MR. Estrogen for Alzheimer's disease in women: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2000;54:295–301. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer F, Reisberg D. Vivid memories of emotional events: the accuracy of remembered minutiae. Mem Cognit. 1990;18:496–506. doi: 10.3758/bf03198482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow AM, Schulkin J, Pfaff DW. Estrogen facilitates fear conditioning and increases corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA expression in the central amygdala in female mice. Horm Behav. 2006;49:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampen DL, Sherwin BB. Estrogen use and verbal memory in healthy postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:979–983. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:83–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Somerville LH, Johnstone T, Alexander AL, Whalen PJ. Inverse amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex responses to surprised faces. Neuroreport. 2003;14:2317–2322. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature. 2006;7:54–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Reiman EM, Bradley MM, Lang PJ, Ahern GL, Davidson RJ, Schwartz GE. Neuroanatomical correlates of pleasant and unpleasant emotion. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1437–1444. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P, Bradley M, Cuthbert B. The International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings. University of Florida: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc ES, Janowsky J, Chan BK, Nelson HD. Hormone replacement therapy and cognition: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2001;285:1489–1499. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc ES, Neiss MB, Carello PE, Samuels MH, Janowsky JS. Hot flashes and estrogen therapy do not influence cognition in early menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:191–202. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000230347.28616.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigland LA, Schulz LE, Janowsky JS. Age related changes in emotional memory. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Carstensen LL, Gottman JM. The Influence of Age and Gender on Affect, Physiology, and Their Interrelations: A Study of Long-Term Marriages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:56–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, Taylor SF, Fig LM, Decker LR, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S. Limbic activation and psychophysiologic responses to aversive visual stimuli. Interaction with cognitive task. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:508–516. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Buss C, Lupien SJ, Pruessner JC. Hippocampal volumes are larger in postmenopausal women using estrogen therapy compared to past users, never users and men: A possible window of opportunity effect. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LF, Anstey KJ, Maller J, Kumar R, Wen W, Lux O, Salonikas C, Naidoo D, Sachdev P. Hormone replacement therapy, brain volumes and white matter in postmenopausal women aged 60–64 years. Neuroreport. 2006;17:101–104. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000194385.10622.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Canli T, English T, Whitfield S, Wais P, Ochsner K, Gabrieli JD, Carstensen LL. Amygdala responses to emotionally valenced stimuli in older and younger adults. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-directed memory: the role of cognitive control in older adults' emotional memory. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Alves SE. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20:279–307. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Murray EA, Malkova L, Mishkin M. Effects of aspiration versus neurotoxic lesions of the amygdala on emotional responses in monkeys. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:4403–4418. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MA, Pfaff DW. Effects of estrogen on activity and fear-related behaviors in mice. Horm Behav. 2001;40:472–482. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, Dolan RJ. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature. 1996;383:812–815. doi: 10.1038/383812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q, Xie J, Wen Z, Weng Y, Shuyun Z. A quantitative MR study of the hippocampal formation, the amygdala, and the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle in healthy subjects 40 to 90 years of age. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:207–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, van Dyck CH, Sano M, Doody R, Koss E, Pfeiffer E, Jin S, Gamst A, Grundman M, Thomas R, Thal LJ. Estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1007–1015. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Gustafsson JA, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression within the human forebrain: distinct distribution pattern to ERalpha mRNA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000a;85:3840–3846. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Keller E, Hurd YL. The human forebrain has discrete estrogen receptor alpha messenger RNA expression: high levels in the amygdaloid complex. Neuroscience. 2000b;95:333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R, Lewis MB. Fear recognition across the menstrual cycle. Horm Behav. 2005;47:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SM, Sherwin BB. Effects of estrogen on memory function in surgically menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:485–495. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90007-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo-Kantola P, Portin R, Polo O, Helenius H, Irjala K, Erkkola R. The effect of short-term estrogen replacement therapy on cognition: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:459–466. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Likhtik E, Pelletier JG, Pare D. Stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex decreases the responsiveness of central amygdala output neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8800–8807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08800.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff R, Bulpitt CJ, Wesnes KA, Rajkumar C. Short-term transdermal estradiol therapy, cognition and depressive symptoms in healthy older women. A randomised placebo controlled pilot cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Fazekas F, Reinhart B, Kapeller P, Fazekas G, Offenbacher H, Eber B, Schumacher M, Freidl W. Estrogen replacement therapy in older women: a neuropsychological and brain MRI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1307–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Estrogen and/or androgen replacement therapy and cognitive functioning in surgically menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1988;13:345–357. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(88)90060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker LH. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2947–2958. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DP, Hillman CH, Duley AR. Influences of age on emotional reactivity during picture processing. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P49–56. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.p49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith YR, Giordani B, Lajiness-O'Neill R, Zubieta JK. Long-term estrogen replacement is associated with improved nonverbal memory and attentional measures in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Fera F, Smith WG, Das S, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS. Functional changes in the activity of brain regions underlying emotion processing in the elderly. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW, Carstensen LL. Autonomic, subjective, and expressive responses to emotional films in older and younger Chinese Americans and European Americans. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:684–693. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, Jackson CA, Frye CJ, Greischar LL, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4415–4425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Sawaya G, Lieberburg I, Grady D. Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women: effects on cognitive function and dementia. JAMA. 1998;279:688–695. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.9.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage J, Brink T, Rose T. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]