Abstract

Objective

To ascertain any differences between care from nurse practitioners and that from general practitioners for patients seeking “same day” consultations in primary care.

Design

Randomised controlled trial with patients allocated by one of two randomisation schemes (by day or within day).

Setting

10 general practices in south Wales and south west England.

Subjects

1368 patients requesting same day consultations.

Main outcome measures

Patient satisfaction, resolution of symptoms and concerns, care provided (prescriptions, investigations, referrals, recall, and length of consultation), information provided to patients, and patients' intentions for seeking care in the future.

Results

Generally patients consulting nurse practitioners were significantly more satisfied with their care, although for adults this difference was not observed in all practices. For children, the mean difference between general and nurse practitioner in percentage satisfaction score was –4.8 (95% confidence interval –6.8 to –2.8), and for adults the differences ranged from –8.8 (–13.6 to –3.9) to 3.8 (–3.3 to 10.8) across the practices. Resolution of symptoms and concerns did not differ between the two groups (odds ratio 1.2 (95% confidence interval 0.8 to 1.8) for symptoms and 1.03 (0.8 to 1.4) for concerns). The number of prescriptions issued, investigations ordered, referrals to secondary care, and reattendances were similar between the two groups. However, patients managed by nurse practitioners reported receiving significantly more information about their illnesses and, in all but one practice, their consultations were significantly longer.

Conclusion

This study supports the wider acceptance of the role of nurse practitioners in providing care to patients requesting same day consultations.

Introduction

General practices need to provide care for patients who request “same day” consultations because they are too ill or otherwise unable to wait for an appointment. The numbers of these “extra” patients are difficult to predict and increasing.1 They are normally seen by general practitioners, although recently nurse practitioners have taken on this work.2–4 The Royal College of Nursing has developed training for nurse practitioners, although there is no requirement for nurses seeing these patients to hold specific qualifications.

Previous studies of nurse practitioners have found high levels of patient satisfaction, low levels of prescribing, and little need to refer patients to general practitioners.4,5 However, these studies were observational and usually involved single practitioners. Our aim was to investigate whether nurse practitioner care differs from general practitioner care for patients requesting same day consultations.

Methods

Recruitment of clinicians

Nurse practitioners were defined as nurses employed in general practice who had completed the nurse practitioner diploma course at eitherthe Royal College of Nursing Institute of Advanced Nursing, or the department of nursing, midwifery, and health care, University of Wales. All nurse practitioners who had completed this training at least one year previously and were working in south Wales or south west England were contacted by their educational institutions. Practices that expressed interest were visited. Relevant local research ethics committees approved the study.

Recruitment of patients and randomisation

Patients seeking a ‘same day’ consultation were recruited. Originally we planned to randomise patients to general practitioner or nurse practitioner care by day of consulting. However, this strategy was not acceptable to all practices so we offered two methods of randomisation (by day and within day). and allowed practices to choose their preferred method.

Patients requesting same day appointments who were prepared to consult either a general practitioner or a nurse practitioner were informed about the study in general terms. Consent was obtained when patients attended the surgery, and they were told which clinician they would see. All practices had a trained member of staff (the project coordinator) to manage the study procedure. under the supervision of the project research officer. The randomisation schemes were generated at the department of general practice in Cardiff, University of Wales College of Medicine.

In practices using randomisation by day, all patients consulting on a particular day saw the same type of practitioner. Practices were supplied with a calendar of their study period with the days allocated at random as nurse practitioner or general practitioner days by block randomisation. Block randomisation was used to ensure balance between the days allocated to the two types of practitioner.

Some of the practices that chose to randomise patients within day had appointments for same day patients fitted in throughout the day while others had unbooked consulting sessions. For practices which had fitted in appointments, the order in which the appointments were to be used was organised according to the block randomisation scheme provided. Sequential, consenting patients were allocated to the consultation slots when they contacted the practices. In the practices that allocated unbooked sessions, patients were allocated on arrival by block randomisation used to ensure a balanced allocation of patients on each day. Patients who seemed too ill or unable to understand the research and women seeking emergency contraceptive advice were excluded. The latter group was excluded to avoid embarrassment to those who might not wish to receive a postal questionnaire. General practitioners were always available to prescribe when necessary.

Outcome measurement and data collection

The primary outcomes were patient satisfaction immediately after the consultation, resolution of symptoms at two weeks, and resolution of concerns at two weeks.6,7 Secondary outcomes included care in the consultation (length of consultation, information provided), resource use (prescriptions, investigations, referrals), follow up consultations, and patients' intentions for dealing with future similar illnesses.

Two patient questionnaires were developed. The first (exit questionnaire) was administered at the time of the consultation. Before the consultation, patients recorded their levels of discomfort and concern on Likert-type scales and provided demographic details. After the consultation, they completed the consultation satisfaction questionnaire8 and answered yes or no to questions on the information provided by the clinician during the consultation (the cause of the illness, what the patient could do to relieve symptoms, likely duration, how to reduce chances of recurrence, and what the patient should do if the problem didn't improve). Completed questionnaires were returned to the project coordinator.

The consultation satisfaction questionnaire has been used by adults to rate general practitioners and nurse practitioners8,9 but not by parents consulting about children. After discussion with the originator of the instrument, we modified the items and tested this questionnaire against the paediatric medical interview satisfaction scale10,11 with 62 patients in a Cardiff practice. The mean difference between scores was −0.33 (SD 7.18) and the limits of agreement were –15.28 to 12.62,12 suggesting no systematic bias between the two methods. The non-completion rate on the paediatric medical interview satisfaction scale was higher than for the modified consultation satisfaction questionnaire. We concluded that the modified consultation satisfaction questionnaire was a reasonable measure of satisfaction for children's consultations and used it for all patients aged 15 or younger.

A second questionnaire was sent to all patients two weeks after their consultation. Patients were asked to record resolution of symptoms and their current level of concern on Likert-type scales, whether they had sought further advice, and how they would deal with future similar illnesses. A single reminder was sent to non-respondents.

Clinicians completed an encounter sheet for each patient, recording length of consultation (including, for the nurse practitioners, any breaks taken); the patient's presenting illness; prescriptions issued; investigations ordered; referrals to other clinicians; and if the patient was asked to reattend.

Four weeks after the initial consultations, patients' medical records were checked for reattendance or hospital admission for the same problem. The results were recorded on an ‘audit sheet’.

Statistical methods

Responses to items on the consultation satisfaction questionnaire were scored on a 1-5 scale, where 5=very satisfied and 1=very dissatisfied. Items scores were summed to produce a total unless data for any component question were missing. Total scores were converted to percentages for analysis. Patient satisfaction was analysed separately for adult and child consultations as the modified consultation satisfaction questionnaire used for children contained one fewer question.

We coded social class from the patient's stated occupation using the Office of Population and Censuses Surveys 1991 standard occupation classification.13 Information on morbidity was obtained from the clinician encounter sheet and the medical records during the audit and this information was categorised to produce a final morbidity coding scheme based on the Royal College of General Practitioners and Office of Population and Censuses Surveys coding system.14

Sample size calculation

Previous studies found mean satisfaction scores of 76.7% (SD 11.4) and that 65% of patients reported resolution of symptoms at two weeks.7,15 Taking a 5% difference in satisfaction and a 10% difference for resolution of symptoms as being of clinical importance, we calculated that sample sizes of 220 and 900 patients were needed for the two outcomes to give 90% power at a significance level of 5%. An inflation factor of 1.5 was used to account for the clusters of patients randomised by day, and we expected to achieve a 70% response rate to the postal questionnaire, giving a recruitment target of 2000 patients to examine both outcomes.

Analyses

Since we used both simple randomisation (within day) and cluster randomisation (by day), we had to assess the effect of the cluster randomisation. We calculated intraclass correlations for each outcome for the practices that used cluster (by day) randomisation using the proc mixed procedure and glimmix macro within SAS software.

All analyses reported include an adjustment for general practice. A general linear model, assuming normally distributed errors, was fitted to the consultation satisfaction questionnaire data and to the consultation time data. Log consultation times were analysed to minimise departures from the model assumptions. Logistic regression was used to compare the two groups for binary outcomes. For these analyses, resolution of symptoms and concerns were grouped into improved (yes or no) and concerned (yes or no) respectively. The results are presented as treatment differences and 95% confidence intervals. A 5% significance level was used throughout.

Results

Recruitment of practitioners

Twenty seven nurse practitioners were identified and sent information. Eighteen expressed interest, seven did not respond, and two declined. Of the 18, 12 were visited and six declined to take part after receiving further information. Ten practices finally agreed to participate (five in south Wales and five near Bristol), with list sizes ranging from 6000 to 16 300 patients. One nurse worked in two practices, both of which took part, and one practice had two nurse practitioners. All were regularly seeing patients requesting same day appointments. No information was gathered on practices that declined to take part.

Randomisation and intraclass correlations

Six practices chose within day randomisation and four chose cluster randomisation by day. The intraclass correlations could not be estimated for three secondary outcomes. Of the 14 intraclass correlations that could be estimated, nine were less than 0.05 and five were between 0.05 and 0.13. These were considered sufficiently small to assume statistical independence within a cluster. We therefore combined data from the two randomisation schemes and conducted analyses at the individual level.

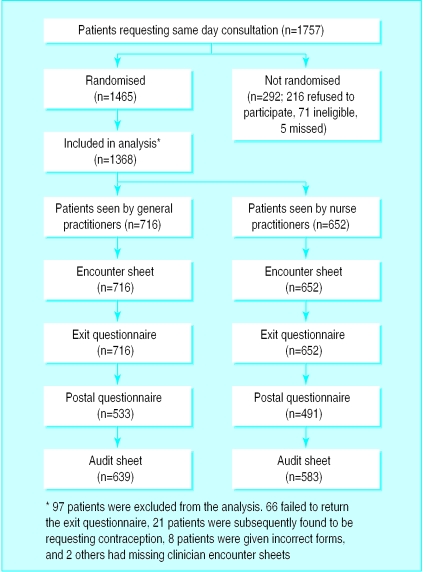

Patient recruitment

The figure shows the flow of patients through the study; 1757 patients requested same day consultations, and data for 1368 were analysed. The patients in the two groups were similar in terms of age, sex, and social class (table 1). In all, 1024 patients (75%) completed the postal questionnaire at two weeks. Audit data from the medical records were available for 1222 patients (89%).

Table 1.

Age, sex, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients studied

| No (%) seeing:

|

||

|---|---|---|

| General practitioner (n=716) | Nurse practitioner (n=652) | |

| Age | ||

| 0-15 | 228 (32) | 244 (38) |

| 16-35 | 211 (30) | 184 (28) |

| 36-55 | 181 (25) | 145 (22) |

| 56-75 | 76 (11) | 63 (10) |

| >75 | 15 (2) | 12 (2) |

| Total | 711 (100) | 648 (100) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 275 (42) | 238 (39) |

| Female | 384 (58) | 373 (61) |

| Total | 659 (100) | 611 (100) |

| Social class | ||

| I | 40 (7) | 39 (7) |

| II | 218 (36) | 173 (32) |

| III non- manual | 161 (26) | 137 (25) |

| III manual | 95 (16) | 102 (19) |

| IV | 71 (12) | 65 (12) |

| V | 25 (4) | 24 (4) |

| Total | 610 (100) | 540 (100) |

There were no notable differences between the two groups in terms of morbidity (table 2) or in initial degree of discomfort or concern. The commonest illnesses presented were respiratory diseases. Eighty nine per cent of patients (632) consulting a general practitioner and 90% (576) of patients consulting a nurse practitioner reported some or a great deal of discomfort. Sixty six per cent of patients (465) consulting a general practitioner and 65% (418) of patients consulting a nurse practitioner reported they were fairly or very concerned.

Table 2.

Presenting illnesses of patients

| Category of disease | No (%) seeing general practitioner (n=692) | No (%) seeing nurse practitioner (n=626) |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory system | 202 (29) | 181 (29) |

| Nervous system and sensory organs | 101 (15) | 90 (14) |

| Skin | 80 (12) | 69 (11) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 60 (9) | 46 (7) |

| Digestive system | 59 (9) | 47 (8) |

| Allergic, endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic | 39 (6) | 48 (8) |

| Genitourinary system | 37 (5) | 32 (5) |

| Miscellaneous | 114 (16) | 113 (18) |

Resolution of symptoms and concerns and patient satisfaction

At two weeks, most patients reported that their symptoms had improved and their concerns were reduced. There were no notable or significant differences between the two modes of care (table 3). The distribution of satisfaction scores was negatively skewed for general practitioner consultations, but for nurse practitioner consultations the scores followed a normal distribution. For children, satisfaction levels were significantly higher for nurse practitioner consultations compared with general practitioner consultations (table 3). There was a significant interaction between mode of care and practice for adults. Significantly higher satisfaction levels for nurse practitioner consultations were observed in three practices, but no significant differences were found in the remaining seven (table 4).

Table 3.

Resolution of symptoms and concerns at two weeks and patient satisfaction immediately after the consultation

| General practitioner | Nurse practitioner | |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution of symptoms (No (%) of patients)* | ||

| Much better | 259 (49) | 235 (49) |

| Better | 191 (36) | 166 (34) |

| Unchanged | 65 (12) | 71 (15) |

| Worse | 10 (2) | 10 (2) |

| Much worse | 4 (1) | 2 (0.4) |

| Total | 529 (100) | 484 (100) |

| Resolution of concerns (No (%) of patients)† | ||

| Not concerned | 233 (44) | 221 (46) |

| Little concerned | 187 (35) | 173 (36) |

| Fairly concerned | 78 (15) | 67 (14) |

| Very concerned | 31 (6) | 23 (5) |

| Total | 529 (100) | 484 (100) |

| Patient satisfaction | ||

| Adults: | ||

| No of patients | 403 | 334 |

| Median (interquartile range) score | 74 (67-80) | 77 (70-82) |

| Children: | ||

| No of patients | 193 | 210 |

| Median (interquartile range) score | 76 (69-82) | 79 (73-87) |

| Mean satisfaction score‡ | 75.62 | 80.40 |

| Difference in mean score | −4.78 (95% CI −6.75 to −2.80) | |

Odds ratio (doctor/nurse) for symptom improvement=1.23 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.73)

Odds ratio (doctor/nurse) for not concerned adjusted for general practice=1.03 (95% CI 0.80-1.33).

Least squares means estimated from fitted model. No overall mean calculated for adults because of interaction between mode of care and practice (see table 4).

Table 4.

Difference in mean percentage satisfaction score for adults by general practice

| Practice | Mean satisfaction score*

|

Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner | Nurse practitioner | ||

| 1 | 68.86 | 77.65 | −8.79 (−13.59 to −3.98) |

| 2 | 72.83 | 72.88 | −0.05 (−3.96 to 3.87) |

| 3 | 79.47 | 75.72 | 3.75 (−3.24 to 10.74) |

| 4 | 71.45 | 75.41 | −3.96 (− 7.70 to −0.22 |

| 5 | 68.66 | 74.58 | −5.92 (−15.70 to 3.86) |

| 6 | 71.58 | 79.53 | −7.95 (−13.58 to −2.31) |

| 7 | 75.02 | 74.41 | 0.61 (−4.84 to 6.05) |

| 8 | 74.28 | 77.49 | −3.21 (−8.71 to 2.29) |

| 9 | 78.70 | 79.24 | −0.54 (−4.88 to 3.81) |

| 10 | 70.93 | 76.83 | −5.90 (−12.11 to 0.31) |

Least squares means estimated from the fitted model.

Care provided

There were no notable differences between the groups in terms of prescriptions issued, investigations ordered, or referrals to secondary care (table 5). Further details for outcomes where odds ratios varied significantly between practices are available on the BMJ 's website. At three of the 10 practices significantly more patients who saw a nurse practitioner were asked to reattend. However, the percentages of patients who actually reconsulted were similar.

Table 5.

Care provided within consultations and patient intentions for managing future illnesses. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise

| General Practitioner (n=716) | Nurse Practitioner (n=652) | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment action | |||

| Prescription issued | 434 (63) | 407 (63) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) |

| Investigation ordered | 73 (11) | 80 (12) | 0.83 (0.58 to 1.16) |

| Referred | 34 (5) | 33 (5) | 0.96† (0.58 to 1.57) |

| Follow up advised‡ | 168 (25) | 222 (35) | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.37) to 1.41 (0.71 to 2.80) |

| Reconsulted for same problem | 182 (29) | 177 (31) | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.17) |

| Provision of information | |||

| Cause of illness | 491 (72) | 501 (81) | 0.58 (0.44 to 0.76) |

| Relief of symptoms | 467 (68) | 548 (86) | 0.32 (0.24 to 0.43) |

| Duration of illness‡ | 388 (57) | 404 (64) | 0.34 (0.14 to 0.84) to 2.38 (0.79 to 7.14) |

| How to reduce chance of recurrence‡ | 139 (21) | 205 (34) | 0.19 (0.09 to 0.38) to 1.57 (0.46 to 5.23) |

| What to do if problem persists | 604 (88) | 584 (93) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.90) |

| Intentions for future treatment | |||

| Treat self | 48 (10) | 50 (11) | — |

| Consult general practitioner‡ | 364 (73) | 211 (48) | 0.76 (0.10 to 5.48) to 11.94 (2.11 to 67.3) |

| Consult nurse | 38 (8) | 139 (32) | — |

| Other | 48 (10) | 37 (9) | — |

| Length of consultation (min) | |||

| No of patients | 648 | 639 | — |

| Median (interquartile range) | 6 (4-8) | 10 (7-14) | — |

| Median (interquartile range) excluding breaks | NA | 8 (6-11) | — |

Adjusted for general practice.

Because of small number of referrals it was not possible to adjust for general practice.

Range reported because odds ratios varied significantly across practices.

In all but one practice, nurse practitioner consultations were significantly longer than general practitioner consultations. The ratio of consultation times between general and nurse practitioners ranged from 0.46 (95% confidence interval 0.39 to 0.54) to 0.90 (0.70 to 1.13). In eight practices the nurse practitioner consultations were significantly longer even after breaks in the consultation (to get prescriptions signed or for other reasons) were excluded. The ratio of consultation times ranged from 0.57 (0.49 to 0.67) to 0.92 (0.70 to 1.21) after breaks were excluded (see BMJ 's website for further details).

Significantly more patients who consulted a nurse practitioner reported that they had been told the cause of their illness, how to relieve their symptoms, and what to do if the problem persisted (table 5). Also, more patients reported being told the likely duration of their illness and how they could reduce the chance of recurrence, although these differences were significant in only three practices.

Of the patients who consulted a general practitioner, 73% (364) stated that they would consult a general practitioner for a similar illness in the future and only 8% (38) indicated that they would consult a nurse (table 5). Of those who saw a nurse practitioner, 48% (211) stated they would consult a general practitioner next time and 32% (139) that they would consult a nurse. However, in six practices the number of patients who would consult a general practitioner in future was not significantly different between the two groups. In the remaining four practices, significantly more patients in the general practitioner group intended to seek general practitioner care in future.

Discussion

We found that patients who consulted nurse practitioners were generally more satisfied with their care, although the differences were less than the level of clinical importance used in the sample size calculation. The variation in mean satisfaction scores for adults between practices suggests that individual clinicians have a big influence. The nurse practitioner consultations were significantly longer and their patients reported being provided with more information. There were no notable differences for the other outcomes studied.

The imposition of the study procedure changed the working arrangements within the practices. We attempted to minimise this by providing flexibility over the method of randomisation. Practices that are considering introducing nurse practitioner care should offer patients a choice.

What is already known on this topic

General practices have to provide care to patients who request same day consultations

Nurse practitioners have extended their role to managing these patients

Care of these patients by nurse practitioners and general practitioners has not been compared in randomised trials

What this study adds

Patients who consulted nurse practitioners received longer consultations, were given more information, and were generally more satisfied

There were no differences for a range of other outcomes, including resolution of symptoms and concerns and prescribing

The study supports the extension of the role of nurse practitioners to include seeing patients requesting same day consultations

We are unaware of other studies comparing the information provided by doctors and nurses. Here most patients reported that their clinician provided information on what to do if symptoms persisted, although lower levels of provision were reported for other important information.16 The nurses' consultations may be longer because they provide more information or because of different time constraints. Longer consultations and those in which more information is provided have been previously associated with greater satisfaction.17,18

Our sample size was smaller than our target based on the assumption that all patients would be randomised by day. However, only four practices chose randomisation by day, and since we found that clustering could be ignored and the combined dataset analysed at the patient level, our sample size exceeded the estimated 900 needed.

Most patients reported high levels of discomfort and concern before their consultation. The questionnaires seem to be responsive since most patients reported reduced symptoms and concerns at two weeks. This may be due to effective treatments or the self limiting nature of the illnesses. If the illnesses were self limiting, it is unsurprising that we found no differences between the two groups in terms of resolution of symptoms.

Patients requiring same day appointments are a diverse group. A third of patients were either not concerned or a little concerned, raising the question of why they consulted. However, some patients may present with early symptoms of serious conditions. The detection of such cases would be important in judging the overall quality of care, but a different study design would be needed.

Previous observational studies found lower levels of prescribing by nurse practitioners and different patterns of patient morbidity.4 We did not find this. As they were given more information, patients seen by nurse practitioners might be expected to cope more effectively with similar illnesses in future. However, similar, small proportions of each group reported that they would self manage future illnesses. This may reflect the contrary effect of prescribing, which was similar in both groups and validates the patient's decision to seek help.

The demands placed on practices mean that they may explore alternative methods of management for same day patients. However, the overall use of resources within the NHS must be considered before widespread changes are made. Nevertheless, the positive outcomes found here suggest that nurses provide a high standard of care to their patients, and this supports their extended role within primary care.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Flow chart showing patient recruitment and follow up

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, nurses, and doctors who took part in this study. Professors Debbie Sharp, Nigel Stott and Richard Baker provided additional valuable support and advice.

Footnotes

Funding: The research was supported by a grant from the Welsh Office of Research and Development for Health and Social Care. CB is supported by a fellowship from the Welsh Office of Research and Development for Health and Social Care. The Research and Development Support Unit at Southmead Hospital is supported by a grant from South West NHS Research and Development Directorate.

Competing interests: None declared.

Two further tables of results are available on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Gill D, Dawes M, Sharpe M, Mayou R. GP frequent consulters: their prevalence, natural history, and contribution to rising workload. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1856–1857. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh GN, Dawes ML. Establishing a minor illness nurse in a busy general practice. BMJ. 1995;310:778–780. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6982.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees M, Kinnersley P. Nurse management of minor illness in general practice. Nursing Times. 1996;92:32–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers P, Lenci B, Sheldon MG. A nurse practitioner as the first point of contact for urgent medical problems in a general practice setting. Fam Pract. 1997;14:492–497. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.6.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salisbury CJ, Tettersell MJ. Comparison of the work of a nurse practitioner with that of a general practitioner. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1988;38:314–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckman H, Kaplan SH, Frankel R. Outcome based research on doctor-patient communication: A review. In: Stewart M, Roter D, editors. Communicating with medical patients. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinnersley P. Bristol: University of Bristol; 1997. The patient-centredness of consultations and the relationship to outcomes in primary care [MD thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker R. Development of a questionnaire to assess patients' satisfaction with consultations in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:487–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulton BC. Use of the consultation satisfaction questionnaire to examine patients' satisfaction with general practitioners and community nurses: reliability, replicability and discriminant validity. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement MJ, Kinnersley P, Howard E, Turton P, Rogers C, Parry K, et al. A randomised controlled trial of nurse practitioner versus general practitioner care for patients with acute illnesses in primary care. Cardiff: Welsh Office of Research and Development; 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis CC, Scott DE, Pantell RH, Wolf MT. Parent satisfaction with children's medical care: development, field test and validation of a questionnaire. Med Care. 1988;24:209–215. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;i:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Standard occupational classification. Vols 1-3. London: HMSO; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royal College of General Practitioners. Morbidity statistics from general practice: third national study 1981-2. London: RCGP, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinnersley P, Stott N, Peters TJ, Harvey I. The patient-centredness of consultations and outcome in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:711–716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helman CG. Culture, health and illness. Bristol: John Wright and Sons; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howie JGR, Porter AMD, Heaney DJ, Hopton JL. Long to short consultation ratio: a proxy measure of quality of care for general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1991;41:48–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart M. Studies of health outcomes and patient-centred communication. In: Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR, editors. Patient-centred medicine—transforming the clinical method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.