INTRODUCTION

Currently, there are more than 5 million Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease (1). It is estimated that approximately 70% of nursing home residents are demented (2). Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms will develop in 70%–80% of patients with dementia living in long-term care facilities (3). Physicians are often requested by the nursing home staff and/or families to assist with difficult behaviors in patients with dementia. However, the nursing staff and/or physicians may not consistently monitor for efficacy and/or side effects for medications prescribed for difficult behaviors. In addition, there is a medical-legal risk of prescribing anti-psychotics (4), and it is unclear how often physicians and/or pharmacists have discussed the risk-benefit ratio of these agents with the surrogate decision-maker. In addition, it is unknown to what extent this important information is documented in the nursing home chart. This is concerning given the increase in psychotropic drug use in long-term care and questions regarding the efficacy and appropriateness of prescribing (5).

Traditional tools to monitor for problems with drug prescribing include monthly visits by the pharmacist which are mandated by federal law (6), the use of the Minimum Data Set which requires monitoring difficult behaviors (7,8), and mandated drug use review by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Outcomes of efforts to improve drug prescribing in long-term care have had limited results. A recent study noted that targeting specific drugs in an effort to reduce potentially inappropriate medication may not be effective (9). A study by Briesacher, et al (10) evaluated whether the nationally required drug use reviews reduced exposure to inappropriate medications in nursing homes. Their study concluded that there was unclear effectiveness of drug use reviews to improve patient safety in the nursing home. The authors called for more creative and useful alternatives for protecting institutionalized residents from medication errors.

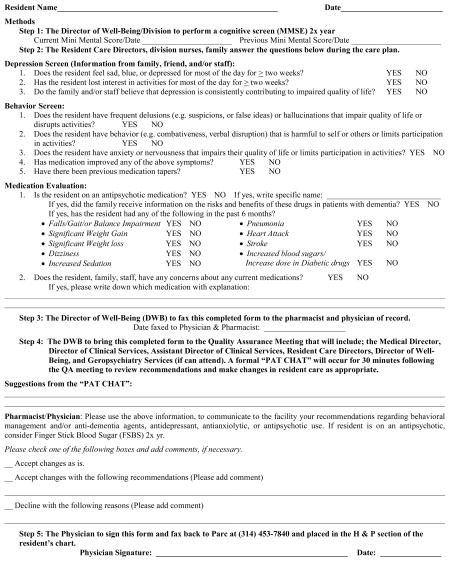

Due to the current limitations in assuring efficacy and/or problems associated with prescribing and monitoring psychotropic agents in long-term care, our facility created a new Quality Improvement (QI) process surrounding the use of these agents to address the following issues; a) to obtain updated and timely information from the family and nursing staff on present and past behavioral problems in long-term care residents with difficult behaviors, b) to determine whether currently prescribed psychotropic drugs have been useful and if not, appropriately tapered, c) to document the presence of possible adverse drug events associated with atypical psychotropic drug use, d) to provide the family or responsible party with updated information on the risk-benefit ratio of antipsychotic drug use, and e) provide updated clinical information to the pharmacist and physician of record to inform continued pharmacological management. This paper describes our first year of experience using the Psychotropic Assessment Tool (PAT) (Appendix 1) as part of our QI process in the long-term care setting.

The Psychotropic Assessment Tool is a short questionnaire developed by the Quality Improvement team of the long-term care facility. It was designed to assess residents mood, anxiety, and behaviors, document those medications used to treat the aforementioned, and any negative side effects that could be attributed to those medications. It was a tool designed to involve the family and interdisciplinary team in improving patient care. We now use the PAT to address current psychiatric symptoms, review the history of symptom stability, discuss whether there has been medication tapers of psychotropic drugs if indicated, discuss the possible need for new medications for behavior or cognition, and review for the presence of any potential side effects attributed to psychotropic drug use. The family is also provided (mailed if not in attendance) with literature on the risk-benefit ratio of antipsychotic use, if the resident was currently on these agents (Appendix 2). This letter was created after consultation with the pharmacist, geriatricians, and local dementia experts in the community.

METHODOLOGY

Setting

Parc Provence is a 120-bed private long-term care facility in St. Louis specializing in dementia care. The facility has the full complement of interdisciplinary services and is affiliated with an academic teaching hospital with both private and academic physicians and opened in May, 2004.

Chart Abstraction

Between the dates of July 2005 and July 2006 all resident charts of patients that were currently in the facility were reviewed by one of the authors (AX) and data was abstracted for the presence of falls, pressure sores, incontinence, delirium, hallucinations, delusions, and fractures. Pain scores (11), AIMS (12), and Braden Scores (13) were also obtained. In addition, laboratory data including creatinine, albumin and hemoglobin levels were recorded. If available, MMSE scores (14) and Allen Cognitive Level scores (15) were obtained and recorded. From the PAT chat information about mood, interest, quality of life, delusions, disruptive behavior, anxiety, antipsychotic use and previous medication taper, as well as improvement in behavior with medication was abstracted. The total number of medications and specific medication use such as antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants at the initiation of the PAT CHAT QI process in July of 2005, and in July 2006 were recorded. We also reviewed and documented the recommendations from the PAT team during this time period. The study was approved by the Washington University Human Studies Committee.

Quality Improvement (QI) Process

The QI team monitored the use of psychotropic agents from the opening of the facility, which was defined as any drug that was prescribed for cognitive impairment and/or difficult behaviors (e.g. cholinesterace inhibitors, NMDA antagonists, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, hypnotics, antiepileptic agents, and/or antipsychotics). The Psychometric Assessment Tool (Appendix 1) was created by the QI team, and fully implemented in July, 2005. The PAT questionnaire is filled out biyearly and on an as needed basis on all patients at two of the quarterly family conference meetings. The family conference meeting involves the interdisciplinary staff which consists of a family member (attends 60–70% of time), a nurse that has contact with the patient on the division, the resident care director (charge nurse that supervises all staff on the division), and social worker. The completed PAT questionnaire is then brought to the next quality improvement meeting where the results are discussed with the interdisciplinary team in a formal discussion called the “PAT CHAT”. These members included; the consulting pharmacist, the medical director, geriatric fellow, resident nurse manager, administrator, and social worker. The team made specific recommendations which could include; titrating up current medications, initiation of new medications, tapering of ineffective medications, continuing appropriate treatment, suggesting safer or more appropriate alternatives, or geropsychiatry consultation. On the PAT form were preprinted orders for the physician of record to check to accept suggested changes, accept changes with additional recommendations, or decline the suggestions. This fax was then returned to the facility by the physician and any new orders were implemented. The PAT form was then placed in the chart as part of the permanent record.

Results

Characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of residents at this long term care community was 83.8 +/− 7.5 years. The residents were primarily female and white, all (100%) with the diagnosis of dementia, compared to the national average of approximately 70%. The mean Mini Mental Status Exam score was 13.5 +/− 7.3, consistent with moderate dementia. The mean Allen Cognitive Level score was 3.8 +/− 0.7 (scale from 1–6. 1 being dependent with all care, 5–6 independent). The majority (58%) were cared for by private community physicians. The average number of prescription medications taken by each resident was 9.9 +/− 3.6 which included multi-vitamins and supplements like calcium and vitamin D.

Table 1.

Description of Patients (N=110)

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Age, years (mean + SD) | 83.8 (7.5) |

| Sex (%female) | 74 |

| Race (% white) | 100 |

| Physician (% University) | 42 |

| Number of Diagnosis (mean +SD) | 6.8 (3.3) |

| Dementia Diagnosis (% with) | 100 |

| Allen Score (mean +SD) | 3.8 (.7) |

| Mini Mental Status Exam (mean +SD) | 13.5 (7.3) |

| Braden Score (mean +SD) | 19.5 (3.3) |

| AIMS scores (means +SD) | 3.64 (4.4) |

| Creatinine (mean +SD) | 1.1 (.4) |

| Hemoglobin (mean + SD) | 12.9 (1.2) |

| Albumin (mean +SD) | 3.8 (.6) |

| Number of Medications | 9.9 (3.6) |

| Prevalence of Difficult Behaviors | |

| Hallucinations | 11% |

| Loss of Interest | 8% |

| Delusions | 21% |

| Disruptive Behavior | 21% |

Common geriatric syndromes and possible medication related side effects were reviewed by retrospective chart review over the past year in an effort to further describe our patient population. Between the dates of July 2005, and July 2006, 73% of the residents had incontinence documented, 45% experienced at least one fall, and 2% had documented fractures. Eleven percent experienced hallucinations, 21% had episodes of documented disruptive behavior, 21% experienced delusions, 24% were documented as being anxious, and 12% were considered to be actively depressed. Side effects commonly attributed to atypical antipsychotic agents were rare; only 7% of residents had weight gain, 9% experienced dizziness, and 5% were noted to be sedated. There were no documented cases of pneumonia, myocardial infarction, or CVA.

Table 2 reveals the percentage of patients taking various psychotropic agents as described at the QI meeting by our pharmacist comparing pre PAT CHAT numbers to those the year following the institution of the PAT QI intervention. The sample size reported for 8/05 represent some patients who were not present at the time of chart abstraction in 8/06 (died or left the facility), and the 8/06 sample size represent some new patients to the facility. These numbers are comparable to the national prevalence of antipsychotic use of 27.6% of all Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes receiving at least 1 prescription of an antipsychotic (5). The percentage of residents on antipsychotics at our facility changed from 26.5% pre PAT CHAT process to 25.2% after the initiation of the PAT CHAT process. Anxiolytics changed from 6%-4%, numbers significantly below the national average use of anxiolytics in long term care facilities of 18.9% (16). Antidepressant use remained about the same at 55.8% and 55.7%, compared to the national averages of 47.4% (16). The use of hypnotics changed from 2.6% to 3.4%, compared to the national average of 4.2% (16). Those residents on Cholinesterase Inhibitors changed from 69% to 61.7%, and those on Namenda changed from 51% to 52.2% pre and post initiation of the PAT CHAT process.

Table 2.

Psychotropic Drug Use

| 8/05 N=113 (%) |

8/06 N=115 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| AChEi | 79 (69) | 71 (61.7) |

| Namenda | 58 (51) | 60 (52.2) |

| Antipsychotics | 30 (26.5) | 29 (25.2) |

| Anxiolytics | 7(6) | 5 (4) |

| Hypnotics | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.4) |

| Antidepressants | 63 (55.8) | 64 (55.7) |

Recommendations to adjust medications were made in 25% of reviews. The majority of the residents (75%) were believed to be stable and no recommendations were made as a result of the PAT CHAT. Fifteen or 13.4% of the residents were found to have active symptoms of depression or anxiety as a result of the PAT and the suggestion was made to increase or add an SSRI, mood stabilizer or anxiolytic. Only five (4.5%) of the recommendations were to taper or discontinue the current antipsychotic and 1 suggestion was to actually increase the antipsychotic dose. Another five suggestions were to taper either an antidepressant or mood stabilizer (valproic acid). Only two (1.8%) of residents were recommended to start memantine as a result of a progression of their disease.

Most importantly we had PAT questionnaires completed and discussed on all residents in the facility over the year evaluated. This means that each individual was discussed with family members and staff. Medications were evaluated. Possible side effects to medications were discussed and changes in medication were made if necessary and all of this was documented on a permanent record for the chart.

Discussion

Our patient population is consistent with demographic characteristics of other long-term care facilities, with a few notable exceptions. The facility focuses only on care for the patient with dementia, making the 100% prevalence rate for dementia much higher than the average long term care facility. The age, gender, moderate degree of dementia as evidenced by the Allen Cognitive Level and MMSE, and the average number of medications, is consisted with data in other nursing home settings. The laboratory data indicate that these patients with numerous co-morbidities (avg 6.5 diagnoses) were relatively stable.

Many facilities that have lower rates of dementia than ours, average 27.6% antipsychotic use across residents (5). We believe that a rate of 25% antipsychotic use in our setting that has a 100% prevalence rate of dementia compares favorably with other institutions. The fact that our rate did not trend to higher use over the course of the study, may be a result of oversight from use of the PAT, use of geropsychiatry referral, the tendency to use other agents due to side effects, and avoidance of antipsychotics due to black box warnings. In addition, there is a high staff to patient ratio, an abundance of activities and resources for treating behaviors with nonpharmacological interventions, and staff highly trained and skilled at dealing with these behaviors. There were few adverse events (e.g. weight gain, sedation, MI, CVA, pneumonia) that could be attributed to atypical antipsychotic agents in this sample over the course of this study. This may represent our small number of patients and short time of observation. However, our system of documenting possible side effects in these newer agents may be more useful than some of the traditional tools such as the AIMS which were created for drugs with a high propensity of extrapyramidal side effects.

Unexpectedly, the initiation of the PAT and the subsequent PAT CHATs did not result in a decline in antipsychotic prescribing. This could be in part due to bias towards admissions of residents with increasingly more difficult behaviors, since the facility does provide specialty care for dementia. We have now documented in writing on our PAT form that the interdisciplinary team met, discussed difficult behaviors, psychotropic drug use, and possible side effects and distributed these recommendations to primary care physicians. We have achieved this goal in 100% of our residents in this study either by documentation in the quality improvement meeting, the medical record, or both. We do not have a comparison of the documentation prior to initiation of the PAT process. However, it was our subjective impression by review of the nursing home record that physician and/or nursing notes were lacking in descriptions and in further adjustments of psychotropic agents prior to the initiation of the PAT process.

When comparing July 2006 to July 2005, there was a change toward fewer number of residents on cholinesterase inhibitors. We believe that this decline is likely the result of discontinuation of the medication as the residents’ dementia progressed and entered a more advanced stage. At the same time, there was an increase in Memantine being prescribed, which is indicated for more moderate to severe dementia (17). Since patients were not consistently on either or both drugs, this remains a potential area of drug prescribing to improve behavior. Both cholinesterace inihibitors (18) and NMDA antagonists (19) have been noted in some studies to improve behavior.

There are several limitations to the current study. This descriptive study utilized a retrospective chart review, and thus limits the ability to make cause and affect relationships. The facility reaches a high socioeconomic resident and is 100% Caucasian. This limits the ability to generalize findings to other settings. In addition, there was no standardized behavioral tool utilized in the assessment of behaviors. We did not collect data to determine whether the primary care physician followed our recommendations. We also do not have a comparison of the documentation and/or interdisciplinary communication prior to initiation of the PAT process. However, it was our subjective impression by review of the nursing home record that physician and/or nursing notes were lacking in descriptions of behavior, documentation of side effects, and the orders indicated few changes in the adjustment of psychotropic agents over time. After the initiation of the PAT process this void of documentation and communication has been filled.

In conclusion, the initiation of the PAT and subsequent PAT CHAT has significantly improved communication between the families, physicians, and the interdisciplinary team. We have improved documentation of the appropriate use of medications, determined whether there were appropriate tapers; documented common side effects associated with psychotropic drug use, and brought this information back to the family and primary care physician so they could be informed. Finally, we have set up a system to provide families with the information on the side effects of antipsychotic medications and documented this in the chart. This last issue is an important one, given the current medico-legal environment.

Appendix 1 Psychotropic Assessment Tool

Appendix 2 Letter

Date

RE: Practice Guidelines for Atypical Antipsychotic Agent Use in Older Adults with Dementia and Behavioral Disturbances

Dear Family and Friends;

It has been noted that the FDA recently came out with a public health advisory regarding untoward deaths from “novel” antipsychotic use in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. Specifically, the FDA reported on a total of 17 placebo controlled trials that were performed with olanzapine (Zyprexa), aripiprazole (Abilify), risperidone (Respirdal), and quetiapine (Seroquel) in elderly demented patients with behavioral disorders. 15 of these trials showed an increase in mortality in the drug treatment group compared to the placebo group. These studies enrolled a total of over 5000 patients and several analyses have demonstrated a 1.6-fold increase in mortality. The specific types of deaths included heart failure, sudden death, or infections (pneumonia). Although these studies are not yet available to us in peer review format, the findings appeared to be robust and need to taken in to consideration when prescribing these types of medications to our patients. It should also be noted that the FDA plans to label these medications with a “black box warning” and they will also likely expand this warning to other medications such as clozapine and ziprasidone (Geodon). Due to these recent findings and the reality that many of us as primary care physicians and consultants prescribe these medications on a routine basis, we have developed a practice guideline on the use of these medications in our Division of Geriatrics and Nutritional Science at Washington University.

Practice Guideline

In many or our patients with dementia and behavioral disturbances, the risk/benefit ratio for prescribing these medications still warrants utilization of these drugs. Each case will need to be reviewed and individualized with a specific determination made as to whether to initiate these types of medications, to taper the drugs to a lower dose, or to discontinue the agents. In any event, it is suggested that the following steps be made in the management of difficult behaviors in the patient with Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type or related disorder:

Efforts should be made to determine the reversibility and identify treatable causes for new behavioral problems in demented patients (e.g. infections such as urinary tract infections, drugs, pain, etc).

Attempts should be made to handle these behavioral difficulties using nonpharmacologic methods such as activities, exercise, and behavioral modifications to avoid environmental triggers.

-

If medications for difficult behaviors are utilized, cholinesterase inhibitors (Arcipet, Razadyne, Excelon) with or without Namenda (memantine) should be considered as first line agents. Then, SSRI’s (a class of antidepressants such as

Zoloft, Celexa, Lexapro, etc) could be utilized in the early stages of the illness, especially if depression or anxiety symptoms are also present.

Attempts to utilize other classes of drugs should also be considered for the management of non-psychotic behavior (e.g. valproic acid, carbamazepine, buspirone, and beta blockers).

If an antipsychotic medication is to be continued or initiated, discussion of the recent FDA findings should be made with the patient and family, and this discussion of the acceptability of these risks documented in the chart. If you have not had this discussion with your physician, we would encourage you to call them if your family member is on one of the atypical antipsychotics noted in the first paragraph above.

Please be aware that our Total Quality Assurance Team as developed a process, to re-examine every residents’ need for these types of agents, and to monitor for possible side effects from these drugs on a regular basis.

Atypical antispsychotic medications can also cause weight gain, sedation, dizziness, and elevated blood sugars. Patients can be monitored for blood sugars and blood pressure problems, based on the dose of the medication, and individual patient characteristics from the patient’s primary physician.

Physician Name

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lindsey J Dahl, Geriatric Fellow at Washington University Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis MO

Rebecca Wright, Consultant Pharmacist for Interlock Pharmacy Systems, Inc. An Omnicare Company.

Aiying Xiao, Research Assistant at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Angela Keeven, Director of Wellbeing and Social Services.

David B Carr, Associate Professor of Medicine and Neurology, Division of Geriatrics and Nutritional Science, Washington University at St. Louis

References

- 1. [Accessed on February 25, 2008];The Alzheimer’s Association Website. 2008 http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp.

- 2.Beers MH, Berkow R. Dementia. In: Beers MH, Berkow R, editors. Merck Manual of Geriatrics. 3. John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Testad I, Aasland AM, Aarsland D. Prevalence and Correlates of Disruptive Behavior in Patients in Norwegian Nursing Homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:916–921. doi: 10.1002/gps.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson Wulsin. Antipsychotics in the elderly: reducing risk of stroke and death. [Accessed on March 4, 2008];The Journal of Family Practice Online. 2005 November;4(11) http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=2825.

- 5.Briesacher BA, Limcangco R, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The Quality of Antipsychotic Drug Prescribing in Nursing Homes. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Accessed on February 26, 2008];The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. (OBRA ’90) http://www.indianamedicaid.com/ihcp/PharmacyServices/pdf/what/omnibus.pdf.

- 7.Hollis Turnham. [Accessed on February 26, 2008];Federal Nursing Home Reform Act from the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 or Simply OBRA ’87. Summary Website http://www.ltcombudsman.org/uploads/OBRA87summary.pdf.

- 8. [Accessed on February 26, 2008];Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Website . http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MinimumDataSets20/

- 9.Lapane KL, Hughes CM, Quilliam BJ. Does Incorporating Medications in the Surveyors’ Interpretive Guidelines Reduce the Use of Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Nursing homes? Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:666–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briesacher BA, Limcangco R, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. Evaluation of Nationally Mandated Drug Use Reviews to Improve Patient Safety in Nursing homes: A Natural Experiment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:991–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couper MP, Tourangeau R, Conrad FG, et al. Evaluating the Effectivess of Visual Analog Scales. Social Science Computer Review. 2006;24:227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergstrom N, Braden B, et al. Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk: A multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale. Nursing Research. 1998;47(5):261–269. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen CK. Occupational therapy for psychiatric diseases: measurement and management of cognitive disabilities. Boston: Little Brown; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.French DD, Campbell RR, Spehar AM, et al. How well do psychotropic medications match mental health diagnosis? A national view of potential off label prescribing in VHA nursing homes. Age and Ageing. 2007;36(1):107–108. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bullock R. Efficacy and safety of memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer disease: the evidence to date. Alzhemier Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:23–29. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000201847.29836.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, et al. A 24 week randomized, double blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:613–620. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maidment ID, Fox CG, Boustani M, et al. Efficacy of Memantine on Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms Related to Dementia: A Systematic Meta-Analysis. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2008;42:32–38. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]