Abstract

Endocytic trafficking of neurotransmitter receptors is critical to neuronal signaling and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Although the importance of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in receptor trafficking in neurons is well established, the contribution of the caveolar/lipid raft pathway has been little explored. Here, we show that caveolin-1, an adaptor protein that associates with lipid rafts and the main coat protein of caveolae, binds to and colocalizes with metabotropic glutamate receptors 1/5 (mGluR1/5). The interaction with caveolin-1 controls the rate of constitutive mGluR1 internalization, thereby regulating expression of the receptor at the cell surface. Consistent with a role for caveolin-1 in mGluR trafficking, we show that mGluR1/5 associate with lipid rafts in the brain and that their constitutive internalization is mediated, in both heterologous cells and neurons, by caveolar/raft-dependent endocytosis. We further show that caveolin-1 attenuates mGluR1-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, an effect that is abolished in cells expressing mutant mGluR1 lacking intact caveolin binding motifs. Neurons from caveolin-1 knock-out mice show enhanced basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation and prolonged ERK1/2 activation in response to stimulation with DHPG [(RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine], a group I mGluR-selective agonist. Together, these findings underscore the importance of caveolar rafts in neurons and suggest that this pathway might play an important role in synapse formation and plasticity.

Introduction

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are G-protein-coupled receptors enriched at excitatory synapses at which they act to regulate glutamatergic neurotransmission. Group I mGluRs (mGluR1/5) activate phospholipase C, leading to Ca2+i mobilization, and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway through which they modulate signal-to-nucleus communication (Hermans and Challiss, 2001). Signaling by mGluR1/5 is critical to synaptic circuitry formation during development (Ichise et al., 2000; Hannan et al., 2001) and is implicated in forms of plasticity including long-term potentiation (Aiba et al., 1994a), long-term depression (LTD) (Aiba et al., 1994b; Huber et al., 2000; Ichise et al., 2000), associative learning (Aiba et al., 1994a), and cocaine addiction (Kenny and Markou, 2004). mGluR1/5 elicit synapse-specific modifications in synaptic strength and spine morphology by stimulating rapid local translation of dendritic mRNAs including Fmr1, encoding FMRP (fragile X mental retardation protein) (Greenough et al., 2001). Recent studies indicate that regulation of mGluR surface expression plays a critical role in neuronal function. For example, mGluR7 surface expression controls cell target-specific plasticity and bidirectional feedforward inhibition (Pelkey et al., 2005). Decreased surface expression of mGluR5 after in vivo exposure to cocaine results in loss of endocannabinoid-mediated retrograde LTD (Fourgeaud et al., 2004). Importantly, reduction of mGluR5 expression in Fmr1 knock-out mice corrects abnormalities underlying fragile X syndrome, including seizures and dendritic spine dysmorphogenesis (Dölen et al., 2007). At present, relatively little is known about the mechanisms controlling trafficking of mGluRs.

Lipid rafts and caveolae are specialized membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids (Simons and Ikonen, 1997). In neurons, membrane rafts are implicated in the establishment of cell polarity (Ledesma et al., 1998), axon guidance (Guirland et al., 2004), normal spine density and morphology (Hering et al., 2003), and receptor signaling (Tsui-Pierchala et al., 2002; Allen et al., 2007) and trafficking (Brusés et al., 2001). Endocytosis can occur via clathrin-dependent or -independent mechanisms (Conner and Schmid, 2003). Lipid rafts and caveolae mediate a form of clathrin-independent endocytosis that is inhibited by depletion of cellular cholesterol (Conner and Schmid, 2003). Caveolin-1, an adaptor protein that associates with rafts and the main coat component of caveolae (Anderson, 1998), can act as a negative regulator of raft-dependent endocytosis by inhibiting internalization of selected cargo (Nabi and Le, 2003). Although clathrin-dependent internalization of neurotransmitter receptors has been extensively documented, little is known about the contribution of clathrin-independent pathways to endocytosis in neurons.

Here, we report that caveolin-1 binds to and colocalizes with mGluR1/5. We show that interaction with caveolin-1 affects the rate of constitutive receptor internalization, thereby regulating the level of expression at the cell surface. Consistent with a role for caveolin-1 in the regulation of receptor trafficking, we show that mGluR1/5 associate with lipid rafts and that their constitutive internalization is partly mediated by caveolar/raft-dependent endocytosis. Consistent with a role for caveolin-1 in the regulation of cell signaling, we further show that caveolin-1 modulates mGluR1/5-dependent activation of ERK–MAPK. Together, these findings underscore the importance of caveolar/lipid raft-mediated trafficking in neurons and suggest that this pathway might play an important role in synapse formation and plasticity.

Materials and Methods

DNA constructs.

DNA subcloning was performed according to standard procedures; mutagenesis was performed by the QuikChange system (Stratagene). The human caveolin-1 cDNA (clone BC006432; Open Biosystems) was subcloned into pCDNA3.0, pEGFP-C1, and pGEX-2T. The mGluR1a-myc construct (with a triple myc in the extracellular N terminus) was a gift from Robert Duvoisin (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR). The tag containing the IgG-binding domain (Z domain) from protein A was inserted at the carboxyl-tail of mGluR1b-myc (Francesconi and Duvoisin, 2002).

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-caveolin-1, mouse anti-caveolin-1, mouse anti-EEA1, mouse mGluR1a (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), rabbit anti-caveolin-1 (N20), rabbit anti-myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-SV2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), mouse anti-MAP2 (AP20; Roche), rabbit anti-MAP2 (Millipore), rabbit anti-mGluR5 (Neuromics; Lab Vision; Millipore), rabbit anti-mGluR1a (Calbiochem), mouse anti-myc (Assay Designs), mouse anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-GluR2 (Millipore).

Cell culture and transfection.

HEK293 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. For cotransfection experiments, either DNAs for receptor and caveolin-1 or receptor and empty vector were mixed at 1:1 ratio. To knockdown caveolin-1, HEK293 cells were plated in 12-well clusters (5 × 104/well) and transfected with control nontargeting small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (ON-TARGET Plus Non-Targeting siRNA pool; Dharmacon) or human caveolin-1-specific siRNAs (ON-TARGET Plus SMARTpools; Dharmacon) alone or together with test plasmids using DharmaFect Duo (Dharmacon) as recommended by the manufacturer. Astrocytes were prepared from the cortices of postnatal day 1 Sprague Dawley rat pups. Dissociated cells were plated in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 2 mm l-glutamine, and maintained in culture for 10–14 d. For rat hippocampal cultures, hippocampi from day 18 [embryonic day 18 (E18)] Sprague Dawley rat embryos or from newborn pups of wild-type and Cav-1−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were dissected, dissociated with 0.05% trypsin, triturated, and plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips. Neurons were maintained in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and GlutaMax (Invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Hippocampal neurons were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation as described by Jiang and Chen (2006) or by nucleofection. For nucleofection, after dissociation with trypsin, hippocampal neurons from E18 rat embryos were washed twice in MEM with 10% FBS and counted. Cells (1–2 × 106) were suspended in 0.1 ml of Primary Hippocampal Neuron Mix (Amaxa) with 2 μg of endotoxin-free DNA (QIAGEN), electroporated with a Nucleofector Device (Amaxa), and plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips in 24-well clusters. Transfected cells were maintained in Neurobasal medium with B27 and GlutaMax for 10–14 d. Cortical neurons (2–4 × 106) were prepared from E18 rat embryos or newborn mouse pups, plated on poly-l-lysine-coated dishes, and cultured for 10 d. Fresh culture medium was added three times a week.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 60 mm β-octylglucoside, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, pH 7.4) containing phosphatase (1 mm Na3VO4) and protease inhibitors (1 mm PMSF and 1 μg/ml each aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. After removing insoluble material by centrifugation, the lysate (0.5–1 mg at 1 mg/ml) was precleared for 2 h at 4°C with protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. For immunoprecipitation (IP) with mouse monoclonal antibodies, rabbit anti-mouse IgG (2.4 μg/ml) was added for 1 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were incubated with protein A-Sepharose for 4 h at 4°C, and washed three times with cold lysis buffer and once with cold phosphate buffer. Proteins were eluted in sample buffer with 100 mm DTT at 50°C for 10 min. For immunoprecipitation from brain tissue, hippocampi from adult rats or cerebella from adult mice were homogenized in buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 320 mm sucrose, and protease inhibitors, and spun at 800 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting pellet was solubilized in buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate), and either 1% Triton X-100 or 60 mm β-octylglucoside for 1 h at 4°C, and spun at 20,800 × g for 40 min. Proteins (0.5 mg) in the soluble extract were immunoprecipitated as described above.

In vitro binding of GST fusion proteins.

pGEX-GST-CAV1 and pGEX-2T were transformed in BL21(D3) Escherichia coli (Stratagene), and protein expression was induced for 5–12 h at 25°C with 1 mm IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Cell pellets were resuspended in cold phosphate buffer with 1 mm PMSF and 1 μg/ml each aprotinin and leupeptin, incubated on ice for 20 min with 100 μg/ml lysozyme and 5 mm DTT, and sonicated. Triton X-100 was added to 1% final concentration for 30 min at 4°C, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. Soluble fusion proteins were recovered by incubation with glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Beads were washed three times with cold phosphate buffer, and fusion proteins were eluted with 10 mm reduced glutathione (Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Eluted proteins were dialyzed against cold phosphate buffer and quantified. For binding assays, transfected HEK293 cells were washed in hypotonic buffer (10 mm Tris-Cl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, pH 8.0) with protease inhibitors, suspended in cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 8), homogenized, and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. After centrifugation (20,000 × g; 30 min), the soluble extract was incubated with 100 μl of IgG-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 16 h at 4°C. The beads were transferred to a column and washed four times with 10 bed vol of IPP150 buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, pH 8.0), two times with IPP500 buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, 500 mm NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, pH 8.0), and two times with binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) with 0.1% Tween 20. Beads with bound receptors were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with precleared GST or GST-Cav-1 (0.1 nmol), washed four times with binding buffer with 0.1% Tween 20, three times with binding buffer, eluted with 100 mm glycine, pH 2.5, and neutralized with 1 m Tris-HCl, pH 9.5. For Western blot, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose filters according to standard procedures, visualized by Ponceau staining, and labeled with primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Labeled proteins were visualized with chemiluminescent substrates (Pierce) by exposure on autoradiography films or by a Kodak Image Station 2000R. Band densities were measured by Kodak 1D Image Analysis software.

ERK–MAP kinase assay.

HEK293 cells were rinsed and incubated with Krebs' buffer (10 mm HEPES, 118 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 25 mm NaHCO3, 1.3 mm CaCl2, 11 mm glucose, pH 7.4) supplemented with glutamic pyruvic transaminase and sodium pyruvate for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were rinsed and either left untreated or stimulated with glutamate (1 mm) for indicated times at 37°C. Cells were placed on ice, rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, extracted with 0.3 ml of lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and sonicated. After removing insoluble material by centrifugation, 40 μg of proteins for each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; clone 12D4), anti-ERK1/2, anti-mGluR1a, and anti-caveolin-1 antibodies. Cortical neurons [15 d in vitro (DIV15)] were incubated with Krebs' buffer containing 2 μm TTX (Tocris) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were rinsed and incubated with Krebs' buffer containing 100 μm (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (RS-DHPG) and TTX for 5 or 20 min at 37°C. Cells were quickly placed on ice and extracted as described previously.

Preparation of detergent-resistant membranes.

All steps were performed at 4°C with ice-cold reagents. Adult rat brain cortices were homogenized in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 320 mm sucrose, and protease inhibitors. The homogenate was spun at 800 × g for 10 min, and the recovered supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was dissolved in 2 ml of cold TNEX buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.4), sonicated for 5 s, and incubated on ice for 10 min. The extract was adjusted to 40% sucrose in TNEX, transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes, overlaid with 6 ml of 30% and 3 ml of 5% sucrose (in TNEX), and centrifuged for 16 h (4°C) at 39,000 rpm (SW40Ti; Beckman Coulter). Thirteen fractions were collected from the top and 25 μl of each used for SDS-PAGE analysis. To prepare detergent-resistant membranes from HEK293 cells, transfected cells (2 × 150 mm plates) were harvested in 2 ml of TNEX, sonicated for 5 s, and incubated on ice for 10 min. The extract was adjusted to 40% sucrose and fractionated on gradients as above.

Biotinylation assays.

HEK293 cells or neurons were placed on ice and rinsed three times with cold PBS, pH 8.0, containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 0.1 mm CaCl2 (PBS2+). After labeling surface proteins with 10 mm Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS2+ for 20 min at 4°C (HEK293 cells) or 8°C (neurons), cells were rinsed twice with 50 mm glycine. To detect surface receptors, cells were first suspended in 0.1 ml of PB buffer (10 mm NaPO4, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA) with 1% SDS and protease inhibitors. The lysate was diluted by adding 0.9 ml of PB with 1% Triton X-100, sonicated, and spun to remove insoluble material. To detect intracellular receptors, after the glycine wash, cells were incubated twice for 15 min at 4°C or 8°C with cold “strip” buffer (50 mm glutathione, 75 mm NaCl, 75 mm NaOH, 10% FBS). After rinsing with cold PBS2+, cells were incubated for 15 min at 4 or 8°C with 1 mg/ml iodoacetamide in PBS2+ with 1% FBS, rinsed twice with PBS2+, and lysed as above. To precipitate biotinylated proteins, equal amount of lysates were incubated with 50 μl of neutravidin beads (Pierce) for 2 h at 4°C, washed three times with PB buffer with 1% Triton X-100, and once with PB buffer without detergent. Bound proteins were eluted by incubating for 30 min at 56°C in sample buffer with 100 mm DTT.

Internalization assays.

Cells were incubated at either 4 or 37°C with 2 μg/ml monoclonal anti-myc antibody (Assay Designs) diluted in either control (MEM, 5.5 mm glucose, 0.1% BSA, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) or test medium (see below). For surface labeling, cells were placed on ice and washed three times with cold PBS2+. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and incubated with 50 mm NH4Cl for 10 min and with blocking solution for 30 min. Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG in blocking solution was added for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS and mounted on glass slides. To simultaneously label surface and total receptors, after live labeling with anti-myc, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, washed, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min at RT. Cells were then incubated with blocking solution, reacted with Cy3-labeled anti-mGluR1a (Zenon Labeling kit; Invitrogen) for 40 min at RT, washed, and mounted. To label internalized intracellular receptors, cells were live labeled with either monoclonal or polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) anti-myc antibody, washed with PBS2+, incubated on ice with strip buffer (0.2 m acetic acid, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 4) for 4 min, rinsed with cold PBS2+, and fixed. Cells were permeabilized and processed for immunolabeling as described above. Acute cholesterol depletion was achieved by incubation at 37°C with 5 mm methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min or 50 μg/ml nystatin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min in control medium. To measure transferrin internalization, HEK293 cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-Transferrin (50 μg/ml; Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37°C in control medium or after cholesterol depletion. To visualize internalized transferrin, cells were placed on ice, acid washed (4 min), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. For K+ depletion, cells were incubated with MEM/H2O (1:1 ratio) for 5 min at room temperature followed by 1 h at 37°C with K+ depletion buffer (20 mm HEPES, 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm glucose, 0.5% BSA, pH 7.4) or control K+ depletion buffer (with 10 mm KCl).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy.

Immunolabeling was performed essentially as described previously (Francesconi and Duvoisin, 2002). Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, incubated for 10 min with 50 mm NH4Cl, and permeabilized at room temperature with either 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min or 0.075% saponin for 30 min. Cells were incubated for 30 min with blocking solution containing 10% goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution were applied overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgGs conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) or Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) in blocking solution. After washing with PBS, coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Prolong (Invitrogen). Labeled cells were visualized by epifluorescence with 60×/numerical aperture (NA) 0.8 or 60×/NA 1.40 oil-immersion objectives mounted on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope and images were acquired with a Spot2 CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Laser-scanning confocal microscopy was performed with an Olympus FV500 system equipped with a 60×/NA 1.40 Plan Apo oil-immersion objective. Image stacks were acquired with a 0.2 μm step. Image files were imported in Photoshop (Adobe Systems) for data presentation and MetaMorph (Molecular Devices) for data quantification.

Quantitative analysis of fluorescence.

Images were acquired keeping illumination and exposure time constant for all conditions. Quantification of surface fluorescence intensity was done with the imaging software MetaMorph. Images were background subtracted and subjected to user-defined intensity threshold, kept constant for all treatments. For each visual field, cells in the same focal plane were manually selected following the cell contour; the calculated integrated pixel intensity of the selected cells was normalized to the thresholded area. To examine colocalization of fluorescence signals in different channels, we used the colocalization function of MetaMorph on images that were background-subtracted and thresholded. For neurons, generally two to four regions of interest were selected in the dendritic fields of each cell analyzed. Colocalization was determined as percentage of pixels that were positive for both receptor and marker analyzed versus total pixels positive for the receptor (100%). Data were collected from images obtained from two independent coverslips per experiment. Data are expressed as means and SEs; statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t test.

Results

mGluR1 interacts with caveolin-1 and associates with lipid rafts

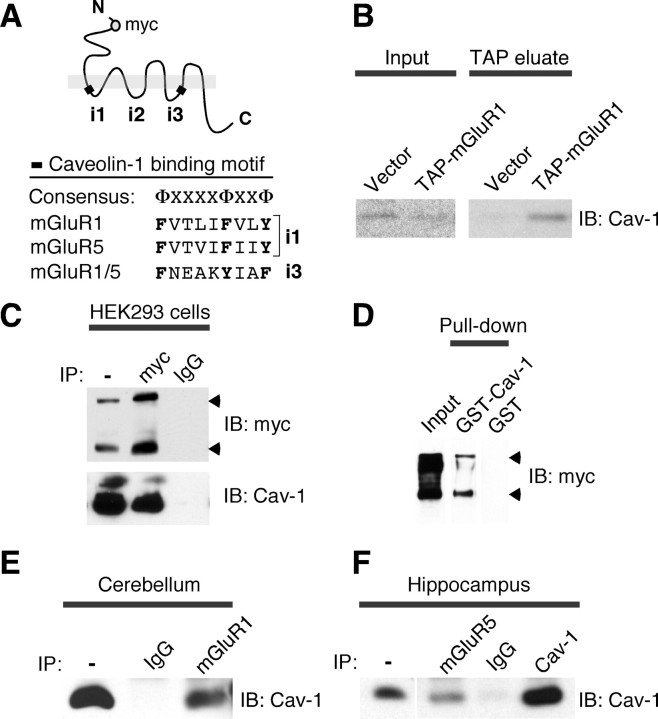

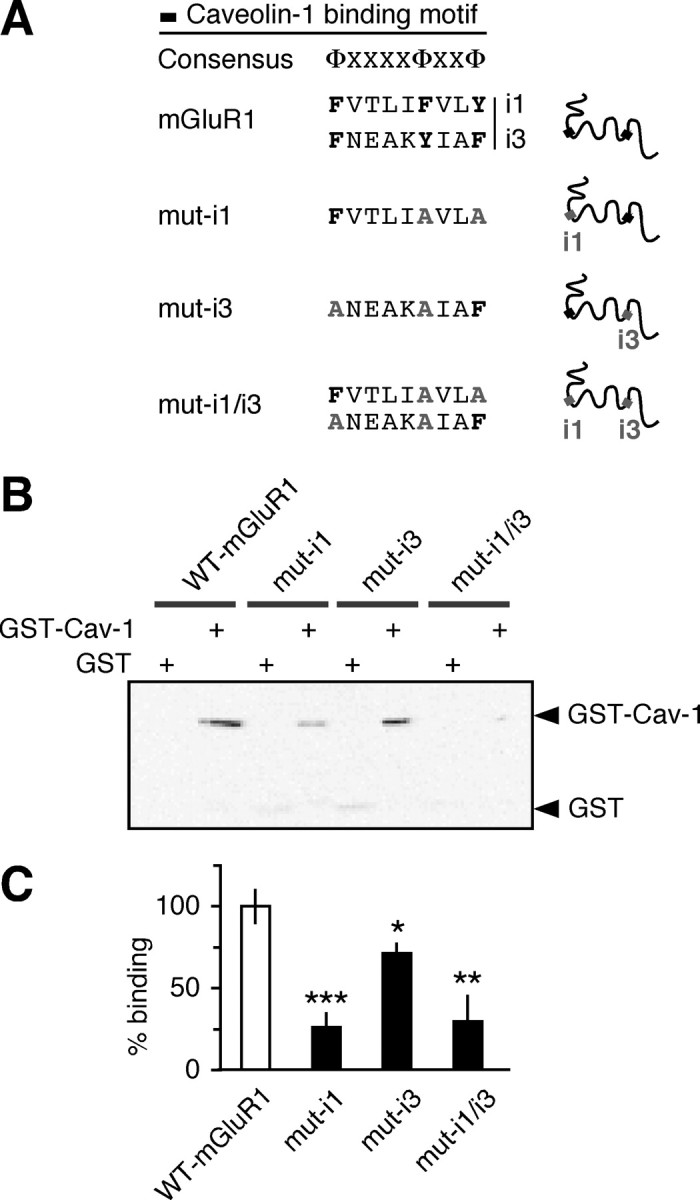

Trafficking of membrane receptors relies on interactions with scaffolding, adaptor, and motor proteins. To identify proteins involved in regulation of trafficking of group I mGluRs, we searched the amino acid sequence of mGluR1 for motifs involved in protein interaction(s). We identified two caveolin-1-binding motifs (Couet et al., 1997), which are located within the first (i1) and third (i3) intracellular loops of mGluR1 and are conserved in mGluR5 (Fig. 1A). To examine whether mGluR1 and caveolin-1 interact, we undertook three different experimental approaches. First, we transfected Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells with mGluR1 tagged with a tandem affinity purification (TAP) cassette (Francesconi et al., 2009) to capture mGluR1-interacting protein complexes formed under native conditions. Protein complexes associated with mGluR1 were recovered from cell extracts by affinity purification of receptors immobilized onto IgG-Sepharose via a TAP tag. Immunoblot analysis of eluted fractions revealed the presence of caveolin-1, which is abundantly expressed in MDCK cells, in the complex associated with mGluR1 (Fig. 1B). Second, we cotransfected myc-tagged mGluR1 and caveolin-1 in HEK293 cells, which express endogenous caveolin-1 at low levels (Wharton et al., 2005), and used an antibody to the myc epitope to immunoprecipitate the receptor. The anti-myc antibody, but not control IgG, precipitated caveolin-1 (Fig. 1C); similarly, an antibody to caveolin-1 precipitated mGluR1-myc (data not shown). Third, we tested whether the interaction between mGluR1 and caveolin-1 can occur in vitro. We performed pull-down assays in which lysates from HEK293 cells expressing mGluR1-myc were applied to immobilized GST-caveolin-1 (GST-Cav-1) or control GST, washed, and collected the eluate containing bound proteins. GST-Cav-1, but not GST, precipitated mGluR1-myc (Fig. 1D), indicating that mGluR1 can interact with caveolin-1 in vitro.

Figure 1.

mGluR1/5 interact with caveolin-1. A, Group I mGluRs contain two putative caveolin-1-binding motifs. Shown is the sequence similarity between consensus and binding motifs in mGluR1 and mGluR5. Aromatic residues that are part of the consensus appear in bold. Φ, Aromatic residues; X, any amino acid. B, Caveolin-1 is part of the protein complex associated with TAP-mGluR1; input lysates and receptor complex were probed with anti-caveolin-1 antibody. C, Caveolin-1 coprecipitates with mGluR1-myc. The mGluR1-myc immunocomplex from transfected HEK293 cells was probed with anti-caveolin-1 and anti-myc antibodies. The arrowheads point to receptor monomer and dimer. D, GST-Cav-1 pulls down mGluR1-myc. GST-Cav-1 and control GST bound to glutathione beads were incubated with lysates from mGluR1-myc transfected HEK293 cells. Bound proteins were probed with anti-myc. E, F, Caveolin-1 coprecipitates with mGluR1/5. The mGluR1 immunocomplex from adult mouse cerebellum (E) and the mGluR5 immunocomplex from adult rat hippocampus (F) were probed with anti-caveolin-1; anti-mGluR1 precipitates ∼3%, whereas anti-mGluR5 precipitates ∼7% of total caveolin-1. IB, Immunoblot.

The finding that mGluR1 interacts with caveolin-1 suggested that the receptor may associate with lipid rafts. To examine this possibility, we extracted the membranes of HEK293 cells expressing mGluR1-myc with cold Triton X-100 and separated the detergent-resistant membrane fractions by centrifugation on sucrose density gradients. Equal volumes of each gradient fraction were analyzed by immunoblot and dot-blot to determine the distribution in the gradient of raft-associated proteins (caveolin-1 and flotillin-1) and lipids [GM1; visualized by labeling with cholera toxin B subunit (ChTxB)] and of proteins excluded from rafts [transferrin receptor 1 (TfR)]. Analysis of detergent-resistant and soluble fractions revealed that mGluR1 localizes to both caveolin-1-enriched and TfR-enriched fractions (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) indicating that the receptor associates with both raft and nonraft membranes.

We next examined whether mGluR1 interacts with caveolin-1 in native tissue and performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with an anti-mGluR1a antibody from extracts of adult mouse cerebellum, in which mGluR1a is abundantly expressed. We found that anti-mGluR1a, but not control IgG, coprecipitated caveolin-1 (Fig. 1E). The presence of conserved caveolin-1-binding motifs suggested that mGluR5 might also interact with caveolin-1. To test this, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments from extracts of adult rat hippocampus (Fig. 1F; supplemental Fig. 2A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and cortical astrocytes prepared from neonatal rat brain (supplemental Fig. 2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We found that an anti-mGluR5 antibody, but not control IgG, coprecipitated caveolin-1 (Fig. 1F; supplemental Fig. 2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), whereas an anti-caveolin-1 antibody coprecipitated mGluR5 (supplemental Fig. 2A,B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) indicating interaction between the native proteins. Together, these findings demonstrate that caveolin-1 is a bona fide binding partner of group I mGluRs.

To examine whether caveolin-1 binds mGluR1 via the putative caveolin-1 binding motifs contained within the first (i1) and third (i3) intracellular loops of the receptor, we generated mutant receptors in which the aromatic residues in the cav-1 binding motifs in the first (mut-i1), third (mut-i3), or both (mut-i1/i3) intracellular loops were replaced with alanine residues (Fig. 2A). Wild-type and mutant receptors containing a TAP tag at the C terminus were expressed in HEK293 cells, purified, and incubated with GST-Cav-1 or GST. Whereas mutation of the caveolin-1 binding motif in the first intracellular loop markedly decreased GST-Cav-1 binding to mGluR1, mutation of the caveolin-1 binding motif in i3 produced a small but significant decrease in caveolin-1 binding (Fig. 2B,C). Disruption of both caveolin binding motifs induced a reduction in GST-Cav-1 binding similar to that observed for mutation of the i1 motif alone (Fig. 2B,C). These findings indicate that caveolin-1 directly interacts with mGluR1 and that its binding is mediated by caveolin-1 binding motif(s) present in the intracellular loops of the receptor.

Figure 2.

Caveolin-1 interacts with mGluR1 via motifs located in the intracellular loops of the receptor. A, Mutations introduced in the putative caveolin-1-binding motifs present in the first (i1) and third (i3) intracellular loops of mGluR1. Critical aromatic residues were substituted with alanine. B, C, Mutations introduced in putative caveolin-1-binding motifs reduce caveolin-1 binding to mGluR1. GST-Cav-1 and control GST were incubated with wild-type and mutant mGluR1 immobilized to IgG-Sepharose. The receptor complex was eluted and probed with anti-GST antibody. Bound GST-Cav-1 is normalized to input receptor; binding to mutants is expressed as percentage of binding to wild-type. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 5; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

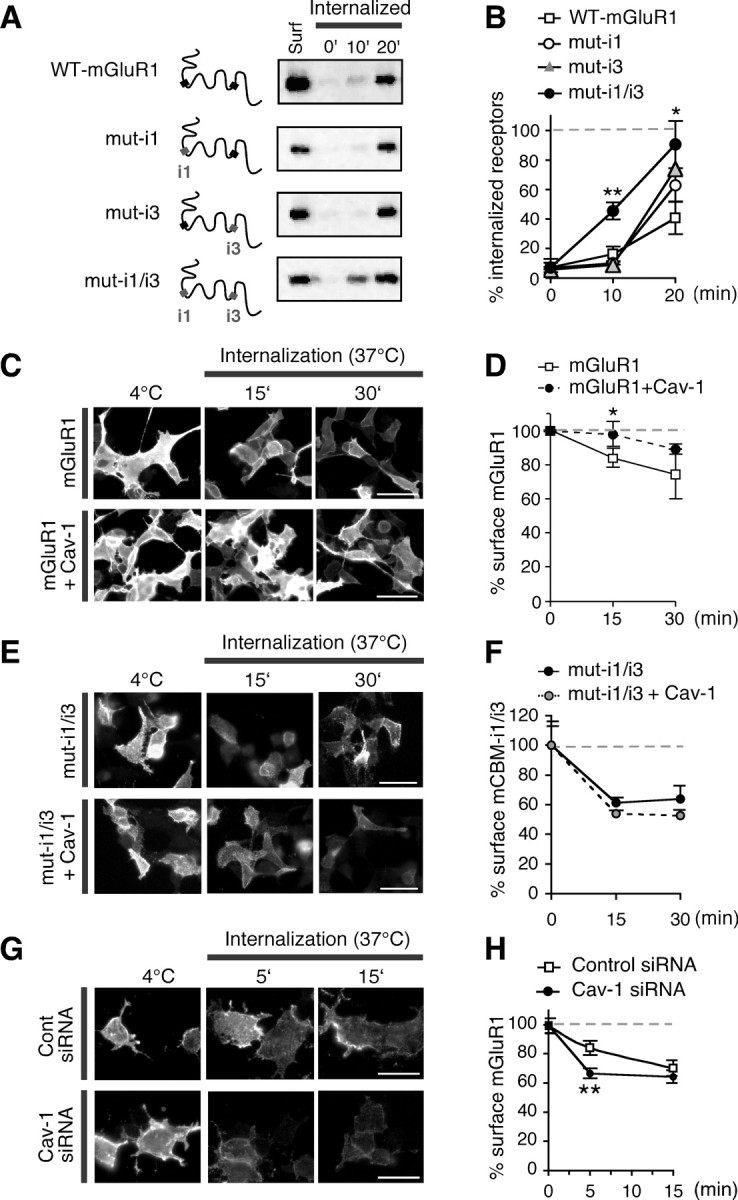

Caveolin-1 regulates the rate of constitutive mGluR1 internalization

Caveolin-1 is implicated in clathrin-independent endocytosis and is thought to act as a negative regulator of caveolae-mediated internalization, presumably by transiently stabilizing caveolae and/or lipid raft associated proteins in membrane microdomains (Nabi and Le, 2003). mGluR1 undergoes constitutive internalization in the absence of stimulation by agonist (Fourgeaud et al., 2003; Bhattacharya et al., 2004) (supplemental Fig. 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), a mechanism that may be critical for the regulation of receptor density at the cell surface. To examine the impact of caveolin-1 on constitutive mGluR1 internalization in HEK293 cells, we undertook three complementary strategies. In one strategy, we reacted live HEK293 cells expressing wild-type mGluR1 and mutant receptors defective in caveolin-1 binding with cell-impermeable cleavable biotin at 4°C and transferred cells to 37°C to initiate internalization in the presence of leupeptin (to inhibit lysosomal proteases). At indicated times, surface-bound biotin was removed by glutathione-containing buffer, and internalized, biotinylated receptors were recovered by precipitation with neutravidin beads. Immunoblot analysis with anti-myc antibody showed that mGluR1 undergoes constitutive internalization in HEK293 cells, as indicated by accumulation of intracellular biotinylated receptors over time (Fig. 3A,B). Disruption of both caveolin-1 binding motifs (but not either motif alone) markedly increased the rate of receptor internalization relative to that of wild-type mGluR1 (Fig. 3A,B). This finding suggests that interaction with both sites is critical to an impact of caveolin-1 on receptor function. In an alternative strategy, we performed live labeling of surface mGluR1-myc with anti-myc antibody at 4°C, transferred cells to 37°C to initiate internalization, and monitored the loss of surface receptors in HEK293 cells expressing the receptor alone or together with cotransfected caveolin-1. To visualize surface receptors, intact cells were fixed and labeled with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 3C); alternatively, to simultaneously visualize both surface and total receptor, after labeling with the secondary antibody, cells were permeabilized and incubated with fluorescent, labeled anti-mGluR1a (supplemental Fig. 4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The specificity of the surface labeling is illustrated by lack of surface immunoreactivity when anti-myc was omitted (supplemental Fig. 4A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In cells expressing mGluR1-myc in the absence of caveolin-1, mGluR1 was removed from the cell surface in the absence of added agonist (Fig. 3C,D; supplemental Fig. 4B,C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Caveolin-1 overexpression slowed the loss of mGluR1-myc from the cell surface, as assessed at 37°C (Fig. 3C,D; supplemental Fig. 4B,C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). To examine the specificity of the impact of caveolin-1 on the rate of mGluR1 internalization, we next performed live labeling of HEK293 cells expressing myc-tagged mut-i1/i3 (lacking both caveolin-1 binding motifs) with anti-myc antibody at 4°C, and monitored loss of surface receptors after incubation at 37°C in the presence or absence of caveolin-1 (Fig. 3E,F; supplemental Fig. 4D,E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Myc-tagged receptors lacking both caveolin-1 binding motifs exhibited substantially faster internalization relative to wild-type receptors (Fig. 3, compare C, D, with E, F; supplemental Fig. 4, compare B, C, with D, E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Moreover, whereas caveolin-1 overexpression slowed the internalization of wild-type receptors, it had no significant impact on the internalization kinetics of the mutant (Fig. 3E,F; supplemental Fig. 4D,E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Next, we used RNA interference to knockdown expression of endogenous caveolin-1 in HEK293 cells and examine the impact of caveolin-1 downregulation on constitutive mGluR1 internalization. siRNAs specific to caveolin-1, but not nontargeting control siRNAs, reduced expression of endogenous caveolin-1 to ∼7% of that in untreated cells (control siRNA, 100 ± 27%, n = 5; cav-1 siRNA, 7 ± 3%, n = 5) (supplemental Fig. 5, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We examined constitutive mGluR1 internalization in HEK293 cells cotransfected with cav-1 or control siRNAs by live labeling of intact cells at 4°C with anti-myc antibody and inducing internalization by incubation at 37°C. At early times (5 min) after incubation at 37°C, mGluR1 was more robustly internalized in cav-1 siRNA-transfected cells compared with control (Fig. 3G,H). Together, these findings indicate that caveolin-1 transiently stabilizes mGluR1 at the cell surface and that disruption of caveolin-1 binding to mGluR1 increases the rate of receptor internalization.

Figure 3.

Caveolin-1 regulates constitutive mGluR1 internalization in HEK293 cells. A, B, Internalization of biotin-labeled wild-type and mutant receptors at 37°C for indicated times. A, Representative immunoblots probed with anti-mGluR1a antibody. B, Summary data for immunoblots like those in A; the percentage internalized receptor is calculated by subtracting abundance of intracellular receptor at t0 from that at a given time point and normalizing to abundance of surface receptor at steady state (Surf, 4°C) [n = 3 (mut-i1 and mut-i3), n = 6 (mut-i1/i3), and n = 5 (wild type); t test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01]. C, D, Constitutive internalization of mGluR1 in cells expressing mGluR1-myc in the absence or presence of caveolin-1. C, Representative images of surface mGluR1-myc at steady state (4°C) and after incubation at 37°C for 15 or 30 min. Shown are cells expressing mGluR1-myc in absence (top) or presence (bottom) of caveolin-1. Scale bars, 50 μm. D, Summary of data in C. Internalization is defined as ratio of surface fluorescence at 37°C versus that at 4°C (n = 3; ≥50 cells analyzed per time point in each experiment). E, F, Internalization of mutant receptors lacking intact caveolin-1 binding motifs (mut-i1/3) in absence or presence of caveolin-1. E, Representative images of mut-i1/i3-myc expressed at the surface of HEK293 cells in absence (top) or presence (bottom) of caveolin-1 at steady state (4°C) and after incubation at 37°C for 15 or 30 min. Scale bars, 50 mm. F, Summary of data in E (n = 3). G, H, Internalization of mGluR1-myc in HEK293 cells transfected with control (top) and cav-1 (bottom) siRNAs. G, Representative images of surface receptors at steady state (4°C) or after incubation at 37°C for 5 or 15 min. H, Summary of data in G. Internalization is defined as ratio of surface fluorescence at 37°C versus that at 4°C; n ≥ 92 cells from three experiments; **p < 0.01. All data are means ± SEM.

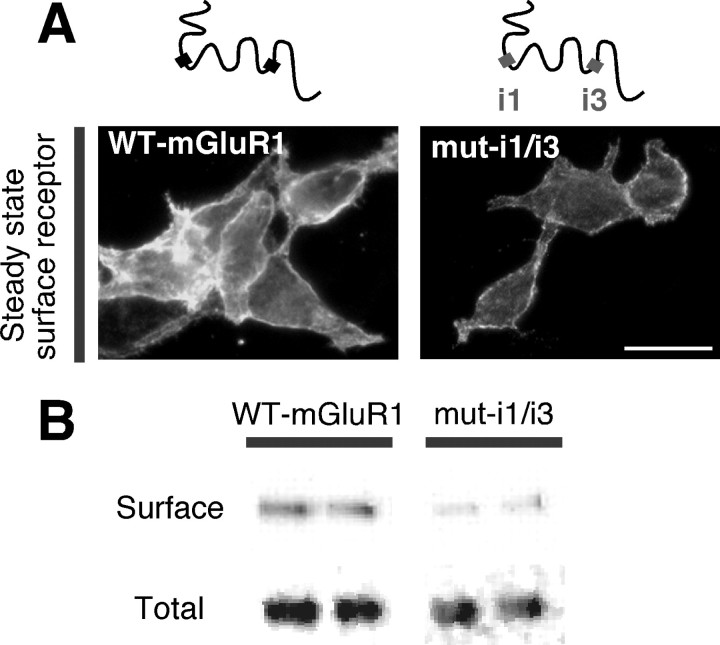

The finding that caveolin-1 acts by regulating the rate of constitutive internalization suggested that interaction with caveolin-1 may affect the overall level of expression of receptors at the cell surface. To test this, we examined the surface expression of wild-type and mutant receptors lacking caveolin-1 binding motifs in HEK293 cells (Fig. 4A). Live intact cells were reacted at 4°C with cell-impermeable biotin; after removal of unbound biotin, labeled surface receptors were recovered from cell lysates by precipitation with neutravidin. Wild-type receptors exhibited high expression at the cell surface of HEK293 cells (Fig. 4A,B). Disruption of both binding motifs markedly reduced surface expression of mGluR1 relative to that of wild-type receptors, as determined by the ratio of biotinylated versus total receptor (wild-type, 100 ± 12%, n = 4 vs mut-i1/i3, 32 ± 12%, n = 6; **p < 0.01) (Fig. 4A,B). Collectively, these findings indicate that the interaction with caveolin-1 can regulate the density of mGluR1 at the cell surface.

Figure 4.

Caveolin-1 regulates mGluR1 surface expression in HEK293 cells. Surface expression at steady state of wild-type and mutant mGluR1 lacking caveolin-1 binding motifs (mut-i1/3) expressed in transfected HEK293 cells. A, Representative images of myc-tagged wild-type and mutant receptors expressed at the cell surface (4°C). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, Representative immunoblots of biotin-labeled (surface) and total receptors probed with anti-mGluR1a antibody.

The caveolar/lipid raft pathway participates in mGluR1 endocytic trafficking

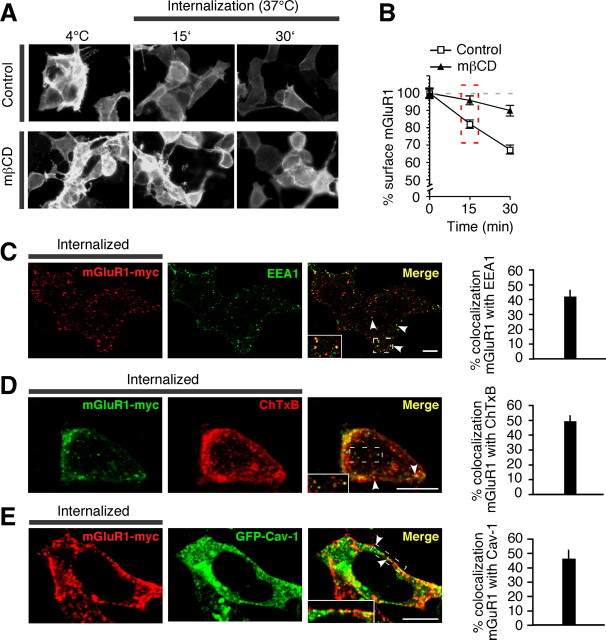

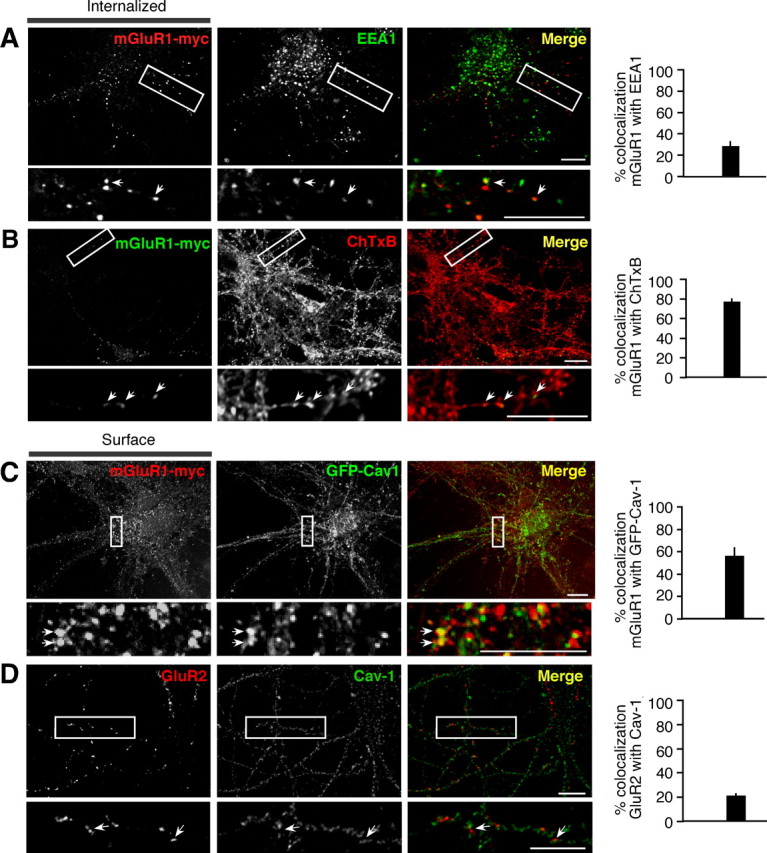

The finding that caveolin-1 regulates the rate of constitutive internalization and the level of mGluR1 expression at the cell surface suggests that lipid rafts might be involved in mGluR1 endocytosis. To investigate this possibility, we first examined the impact of two agents that inhibit/disrupt lipid rafts, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (mβCD), which depletes cholesterol, and nystatin, which sequesters cholesterol (Di Guglielmo et al., 2003) (but see Rodal et al., 1999), on mGluR1 internalization in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells expressing mGluR1-myc were incubated with mβCD (60 min), nystatin (30 min), or control medium at 37°C, live labeled with myc antibody at 4°C, and transferred to 37°C to induce internalization. Treatment of cells with mβCD (Fig. 5A; supplemental Fig. 6A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) or nystatin (not illustrated) decreased the fraction of surface mGluR1 that was internalized (fluorescence remained at surface at 15 min vs t0 in control 84 ± 3% compared with mβCD 107 ± 16%, n = 4; p < 0.05) (Fig. 5B; supplemental Fig. 6B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In contrast, these treatments had little or no effect on uptake of transferrin, a process mediated by the transferrin receptor, a marker of nonraft membrane fractions (supplemental Fig. 6C,D, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These findings indicate that internalization of mGluR1 occurs, at least in part, via raft-mediated endocytosis. Next, we examined targeting of internalized mGluR1 to caveolae/raft-derived endocytic vesicles. HEK293 cells expressing mGluR1-myc were live labeled with an anti-myc antibody at 4°C, transferred to 37°C to stimulate internalization, and then acid treated to remove surface-bound antibody for visualization of internalized receptors. At early time points, a substantial fraction of internalized mGluR1-myc was present in early endosomes marked by EEA1 labeling (42.08 ± 3.99%; n = 13; 15 min at 37°C) (Fig. 5C). We next monitored targeting of mGluR1 to caveolar/raft derived endosomes. Toward that end, we marked raft-derived endosomes with Alexa Fluor-tagged ChTxB (1 μg/ml), a protein that binds the raft-associated ganglioside GM1 and is internalized via caveolae and/or lipid rafts (Parton et al., 1994) (but see Shogomori and Futerman, 2001), by performing cointernalization assays. After 15 min at 37°C, 49.44 ± 3.51% (n = 33) of internalized receptors localized to ChTxB-positive vesicles (Fig. 5D), indicative of targeting to caveolar/raft-derived vesicles. Mutant receptor mutants lacking both caveolin-1 binding domains (mut-i1/3) also showed extensive localization to ChTxB-positive vesicles after 15 min at 37°C (57.01 ± 5.90%; n = 11) (supplemental Fig. 6E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In cells coexpressing mGluR1-myc and GFP-caveolin-1 (GFP-Cav-1), a substantial fraction of internalized receptors localized to GFP-Cav-1 containing vesicles (45.85 ± 6.27%; n = 22; at 30 min) (Fig. 5E), indicating localization to caveosomes, a vesicular compartment of the caveolar pathway. These findings indicate that constitutive mGluR1 internalization in HEK293 cells proceeds, at least in part, via caveolar/raft-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 5.

mGluR1 internalizes via the caveolar/raft pathway in HEK293 cells. A,B, Constitutive mGluR1-myc internalization is partially inhibited by cholesterol depletion with mβCD. A, Representative images of surface mGluR1-myc at steady state (4°C) and after internalization for 15 and 30 min at 37°C. B, Quantification of internalization from images like those in A assessed as loss of surface fluorescence after incubation at 37°C versus surface fluorescence at 4°C. Shown are means ± SEM from a representative experiment with n ≥ 111 cells analyzed per time point. C, Representative images and quantification of internalized (15 min) mGluR1-myc present in early endosomes marked by EEA1. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 13). D, Representative images and quantification of internalized (15 min) mGluR1-myc in vesicles labeled by ChTxB. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 33). E, Representative images and quantification of internalized (30 min) mGluR1-myc in vesicles positive for GFP-Cav-1. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 22). Colocalization appears in yellow in merged images. The arrowheads point to double-labeled vesicles. Scale bars, 10 μm.

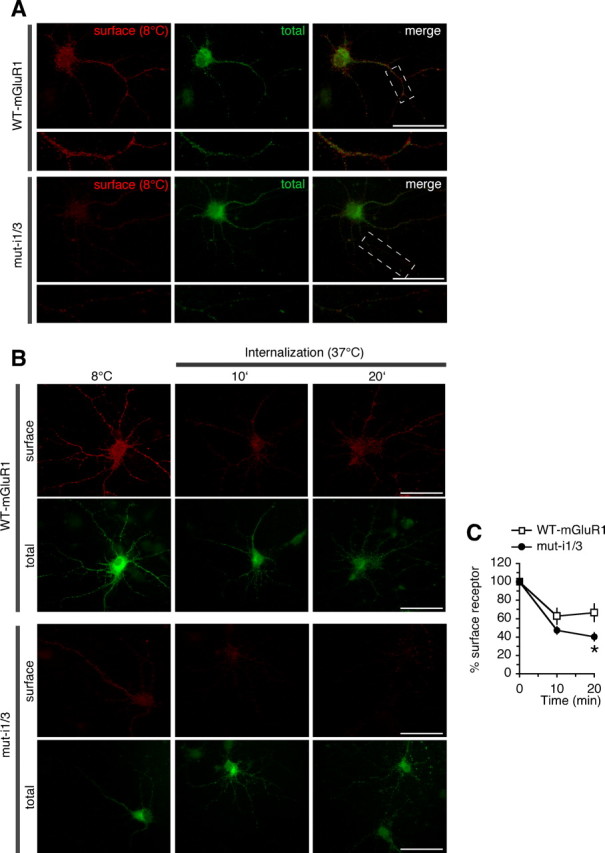

To examine whether the caveolar/raft pathway contributes to constitutive mGluR1 internalization in neurons, we undertook two experimental approaches. First, we transfected neurons with mGluR1-myc, performed live labeling with anti-myc antibody at 37°C for 30 min, and examined constitutive (without added agonist) receptor internalization by removing surface-bound antibody by acid strip and labeling endocytic vesicles. Approximately 30% of internalized mGluR1-myc localized to early endosomes marked by EEA1 (hippocampal neurons, 27.84 ± 4.62%, n = 15; cortical neurons, 27.26 ± 3.58%, n = 46) (Fig. 6A). To determine whether receptors localized to vesicles derived by caveolar/raft endocytosis, we performed cointernalization experiments of mGluR1 with ChTxB and found that a substantial fraction of internalized receptors colocalized with ChTxB (76.68 ± 3.36%; n = 19; hippocampal neurons) (Fig. 6B). Surface mGluR1-myc localized to discrete clusters that extensively overlapped with cotransfected GFP-Cav-1 (Fig. 6C); in contrast, caveolin-1 showed little overlap with the GluR2 subunit of AMPA receptors (Fig. 6D). Together, these findings indicate that in neurons mGluR1 partitions, at least in part, to membrane domains enriched in caveolin-1 and engages the caveolar/raft pathway for constitutive internalization. Next, we examined surface expression and internalization of mGluR1 and a mutant lacking intact caveolin-1 binding motifs (mut-i1/3) expressed in hippocampal neurons. To determine whether interaction with caveolin-1 regulates the density of receptors expressed at the neuronal surface, we compared surface expression at steady state of mutant versus wild-type receptors (Fig. 7A). Live neurons (DIV14) were labeled at 8°C with anti-myc antibody, washed, and fixed; surface receptors were visualized by labeling with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody, whereas total receptors were detected after permeabilization by labeling with an antibody directed to the carboxyl tail of mGluR1a and an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody. We found that surface expression of mut-i1/3 was significantly decreased compared with mGluR1, as determined by the ratio of surface versus total receptor (wild-type 100 ± 12% vs mut-i1/i3 49 ± 7%, n = 68; p < 0.001) (Fig. 7A). To examine the rate of internalization of wild-type and mutant receptors, live neurons were labeled at 8°C with anti-myc antibody, washed, incubated at 37°C for indicated times, and fixed. Comparison of the rate of internalization relative to receptor surface levels at steady state (8°C) showed increased internalization of the mutant receptor compared with wild type (Fig. 7B,C). Together, these findings indicate that, in neurons, mGluR1 can internalize via the caveolar/raft pathway and that its interaction with caveolin-1 regulates its expression level in the neuronal plasma membrane.

Figure 6.

mGluR1 colocalizes with markers of the caveolar/raft pathway in neurons. A, B, mGluR1 undergoes constitutive internalization in neurons and localizes to vesicles labeled by ChTxB. A, Representative images and quantification of internalized (37°C; 30 min) mGluR1-myc present in early endosomes marked by EEA1. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 15). B, Representative images and quantification of internalized mGluR1-myc (37°C; 30 min) present in ChTxB-positive vesicles. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 19). C, mGluR1-myc expressed at the neuronal surface localizes to discrete clusters that overlap with GFP-Cav1. Surface receptors were visualized by live labeling of neurons with anti-myc antibody (8°C; 30 min). Shown are means ± SEM (n = 14). D, GluR2 expressed at the neuronal surface of hippocampal neurons shows little overlap with caveolin-1. Shown are deconvolved epifluorescence images. Surface receptors were visualized by live labeling of neurons with an anti-GluR2 antibody (8°C; 30 min). Shown are means ± SEM (n = 49). The arrows point to areas of colocalization that appear in yellow in merged images; the boxed regions are shown magnified in insets. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Figure 7.

Caveolin-1 regulates constitutive mGluR1 internalization and surface expression in neurons. A, Disruption of caveolin-1 binding motifs in mGluR1 decreases receptor surface expression in neurons. A, Representative images of surface and total mGluR1 (top panels) and mut-i1/3 (bottom panels) in hippocampal neurons at steady state. The boxed regions are shown magnified below. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, C, Constitutive internalization of wild-type mGluR1-myc and mut-i1/3-myc expressed in hippocampal neurons (DIV14). B, Representative images of surface and total receptors at steady state (8°C) and after internalization at 37°C for 10 and 20 min. Scale bars, 50 μm. C, Quantification of images like those in B; receptors internalization was calculated from normalized surface expression (surface/total fluorescence) at 37°C compared with the respective level at steady state (8°C). Shown are means ± SEM [mGluR1 (n ≥ 15), mut-i1/3 (n ≥ 12); *p < 0.05].

The caveolar/lipid raft pathway participates in internalization of native mGluR5 in neurons

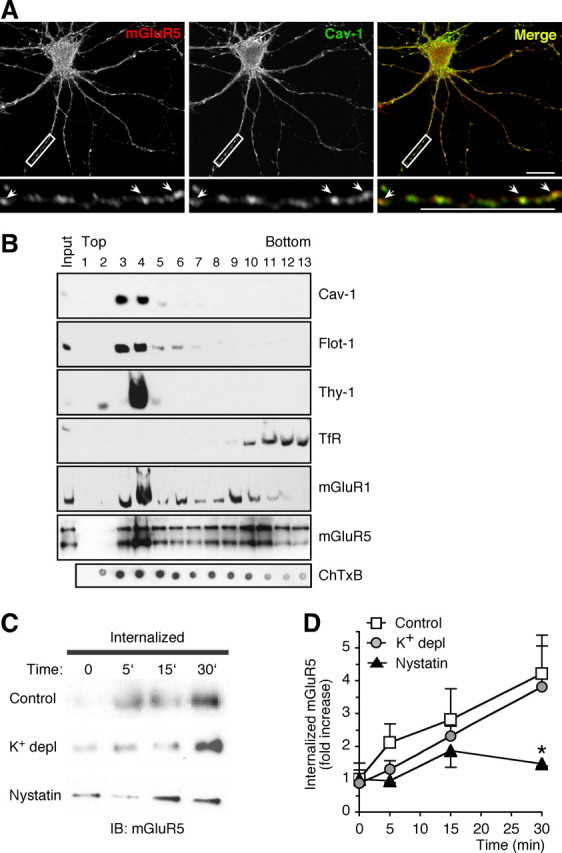

Our findings thus far provide evidence for the involvement of the caveolar/raft pathway in constitutive endocytosis of mGluR1 in both heterologous cells and neurons and they further reveal a role for caveolin-1 in regulating surface expression of mGluR1. However, they do not provide direct evidence for the involvement of the caveolar/raft pathway in endocytosis of native mGluRs in the brain. To address this question, we used three different approaches to examine the involvement of the caveolar/raft pathway in mGluR5 trafficking. mGluR5 was chosen for these studies because (1) it is more abundantly expressed than mGluR1 in both cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons, thus greatly facilitating its detection by biochemical and immunolabeling approaches, and (2) it contains cav-1 binding motifs within its intracellular loops that are essentially identical with those contained in the intracellular loops of mGluR1 (Fig. 1A). First, we used immunolabeling with specific caveolin-1 antibodies, as assessed by lack of immunoreactivity in brain extracts and neurons from Cav-1 KO mice (supplemental Fig. 7B–D, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), to determine whether mGluR5 and caveolin-1 are colocalized in neurons. Native mGluR5 exhibited considerable overlap with endogenous caveolin-1 (Fig. 8A), which is expressed at relatively high levels in the somata and neurites of hippocampal neurons (supplemental Fig. 7A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Second, we examined whether group I mGluRs associate with lipid rafts in vivo. We isolated detergent-resistant membranes from the cortices of adult rat brain by incubation with cold Triton X-100 and fractionation on sucrose density gradients. Fractions containing lipid rafts were identified by enrichment of GM1, the GPI-anchored protein Thy-1, caveolin-1, and flotillin-1, whereas nonraft fractions were identified by enrichment of transferrin receptor (Fig. 8B). Western blot analysis with anti-mGluR1a and anti-mGluR5 antibodies showed that a subset of both receptors (∼62% of mGluR1a and ∼35% of mGluR5, respectively) is present in membrane rafts and cofractionate within caveolin-1-containing rafts (Fig. 8B). Third, to examine whether the caveolar/raft pathway participates in constitutive internalization of native mGluR5, live neurons were incubated with nystatin or control medium supplemented with leupeptin for 30 min at 37°C. Neurons were then incubated with cell-impermeable, cleavable biotin at 8°C, washed, and further incubated in the same medium at 37°C. At indicated times, biotin was removed from the cell surface, and internalized, biotinylated receptors recovered by precipitation with neutravidin beads. Under control conditions, internalized, biotinylated receptors accumulated with time, as assessed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8C,D). Internalization of mGluR5 was agonist independent, in that it occurred at a similar rate in the absence or presence of α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG) (control vs MCPG: 2.83 ± 0.56 vs 3.67 ± 1.51, n = 4, p > 0.1 at 5 min; 4.47 ± 1.21 vs 1.92 ± 0.17, n = 6 and n = 4, p > 0.1 at 15 min; 6.17 ± 1.56 vs 3.09 ± 0.68, n = 6 and n = 4, p > 0.1, at 30 min), and was not significantly inhibited by K+ depletion, a treatment that inhibits clathrin-mediated endocytosis (supplemental Fig. 6, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), in agreement with reports by others (Fourgeaud et al., 2003). Membrane cholesterol sequestration with nystatin markedly inhibited accumulation of internalized mGluR5 (Fig. 8C,D). Collectively, these results indicate that the caveolar/raft pathway is important to constitutive internalization of group I mGluRs in the brain.

Figure 8.

Native mGluR5 colocalizes with caveolin-1, associates with lipid rafts, and internalizes via the caveolar/raft pathway. A, Endogenous mGluR5 and caveolin-1 colocalize in neurons. Shown are representative images of a labeled hippocampal neuron at DIV9. Areas of colocalization are indicated by arrows and appear in yellow in the merged image. The boxed regions are shown magnified below. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, mGluR1/5 associate with lipid rafts in the brain. Rat brain membranes were extracted with Triton X-100 and separated on sucrose density gradients. Thirteen fractions were collected starting from the top of the gradient; equal volumes from each fraction were analyzed by immunoblot for the indicated proteins. Exposure time was kept constant (1 min) for all immunoblots except mGluR5 (10 s); input, total extract. Binding of ChTxB to GM1 was assayed by dot blot. C, D, Constitutive mGluR5 internalization in neurons is mediated by the caveolar/raft pathway. C, Representative immunoblots probed with anti-mGluR5 illustrating intracellular accumulation of biotinylated mGluR5 in control and treated cortical neurons. D, Quantification of intracellular biotin-labeled mGluR5; receptor internalization is expressed as fold increase of the ratio of intracellular versus total receptor compared with t0 (4°C). Shown are means ± SEM (control, n = 7; K+ depletion, n = 7; nystatin, n = 5; *p < 0.05).

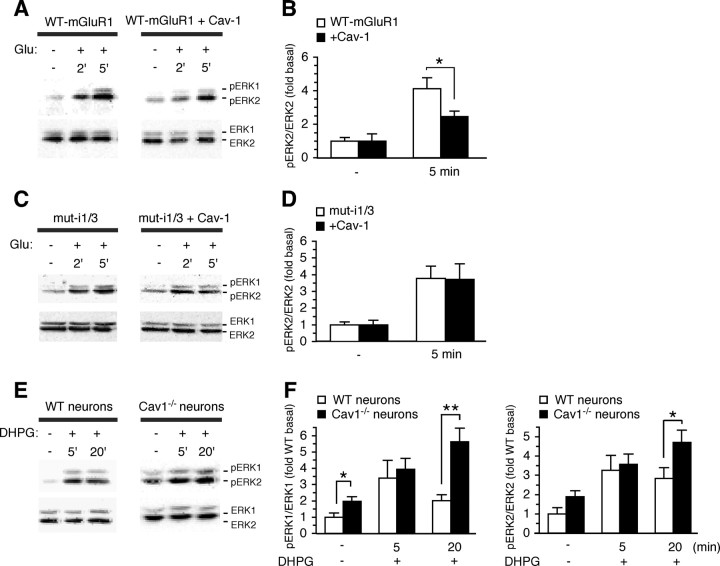

Association with caveolin-1 regulates mGluR1-dependent phosphorylation of ERK–MAPK

The results thus far indicate that caveolin-1 interacts with group I mGluRs, but do not address the impact of caveolin-1 on mGluR function. To examine whether caveolin-1 regulates group I mGluR signaling, we expressed mGluR1 in the absence or presence of caveolin-1 in HEK293 cells, and measured glutamate-stimulated, mGluR1-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation. HEK293 cells do not express endogenous glutamate receptors and express caveolin-1 at low levels, and thus provide a suitable system for these experiments. In cells expressing mGluR1 in the absence of caveolin-1, stimulation by glutamate (1 mm) induced an approximately fourfold increase in ERK2 phosphorylation compared with basal levels, as assessed by immunoblots probed with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and anti-ERK1/2 antibodies. Phosphorylation of ERK2 was evident at 2 min and maximal by 5 min (Fig. 9A,B), after which it declined to basal levels (data not shown). Caveolin-1 overexpression did not significantly alter basal ERK2 phosphorylation, but decreased glutamate-dependent ERK2 phosphorylation relative to cells expressing mGluR1 in the absence of caveolin-1 (Fig. 9A,B). To examine the specificity of the impact of caveolin-1 on mGluR1 function, we expressed a mutant receptor lacking both cav-1 binding motifs (mut-i1/3) in HEK293 cells in the absence or presence of exogenous caveolin-1 and monitored glutamate-elicited ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 9C,D). Application of glutamate to cells expressing the mutant receptor in the absence of exogenous caveolin-1 increased the abundance of phospho-ERK2 relative to that under basal conditions (Fig. 9C,D). Overexpression of caveolin-1 in cells expressing mutant receptor did not significantly alter the maximal level of glutamate-induced phospho-ERK2 (Fig. 9C,D). These findings indicate that caveolin-1 modulates mGluR1 signaling and that the functional impact of caveolin-1 on mGluR1 requires intact caveolin-1 binding motifs.

Figure 9.

Association with caveolin-1 regulates mGluR1/5-mediated activation of ERK–MAPK. A, Representative immunoblots for pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 of lysates from HEK293 cells expressing mGluR1 with or without cotransfected caveolin-1 and stimulated with glutamate (1 mm) for indicated time. B, Quantitative analysis of experiments like those in A; glutamate-induced ERK2 phosphorylation is calculated as ratio of the band densities of pERK2/ERK2, which fall within a linear range (data not shown) normalized to basal level. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 6; *p < 0.05). C, Representative immunoblots for pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 from HEK293 cells expressing mut-i1/i3 with or without cotransfected caveolin-1 and stimulated with glutamate. D, Quantitative analysis of experiments like those in C. Shown are means ± SEM (n = 4). E, Representative immunoblots for pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 of lysates from wild-type and Cav-1−/− cortical neurons under basal conditions or after stimulation with DHPG for the indicated time. F, Quantitative analysis of experiments like those in E; ERK1/2 phosphorylation is calculated as ratio of the band densities of pERK1/ERK1 or pERK2/ERK2 normalized to basal level of wild-type neurons. Shown are means ± SEM (n > 6; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To examine the impact of caveolin-1 on signaling by native group I mGluRs, we monitored mGluR1/5-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in cortical neurons from wild-type and caveolin-1 null (Cav-1−/−) mice. Endogenous mGluR1/5 were activated by application of RS-DHPG (100 μm), a selective agonist for group I mGluRs, for 5 or 20 min. Under basal conditions, the levels of phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2 were higher in Cav-1−/− neurons compared with wild-type neurons (Fig. 9E,F). Stimulation with DHPG for 5 min induced an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both wild-type and Cav-1−/− neurons. Prolonged exposure to DHPG (20 min) did not further increase ERK1/2 phosphorylation in wild-type neurons; in contrast, in Cav-1−/− neurons prolonged stimulation by the agonist resulted in sustained ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 9E,F). Together, these findings indicate that caveolin-1 is a physiologically relevant regulator of group I mGluR trafficking and signaling in the brain.

Discussion

In this study, we identify caveolin-1 as a binding partner for group I mGluRs and demonstrate that caveolin-1 regulates receptor trafficking. Several findings indicate that the interaction of caveolin-1 with mGluRs is specific and occurs via direct binding to the receptors. First, we show that caveolin-1 interacts with mGluR1/5 in both heterologous cells and brain lysates. Second, we show that the interaction is mediated by caveolin-1 binding motifs contained within the intracellular loops of the receptor. Third, we show that native caveolin-1 and mGluR5 colocalize in neurons. Fourth, we show that a subset of endogenous mGluR1/5 associates with rafts in the brain. Caveolin-1 therefore meets criteria expected for a physiologically relevant mGluR1/5 interacting protein. We further show that caveolin-1 regulates mGluR1/5 trafficking and signaling. Caveolin-1 attenuates the rate of constitutive mGluR1 endocytosis in HEK293 cells and neurons, thereby increasing the number of receptors at the cell surface. A subset of brain mGluR1/5 associates with lipid rafts and internalizes, at least in part, via raft-dependent endocytosis. Caveolin-1 also attenuates mGluR1-mediated activation of ERK–MAPK signaling, an effect that requires direct binding of caveolin-1 to mGluR1 via its cav-1 binding motifs. Consistent with this, neurons from caveolin-1 knock-out mice show enhanced basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation and prolonged ERK1/2 activation in response to stimulation with the group I mGluR-selective agonist DHPG. To our knowledge, our findings provide the first evidence for a role of the caveolar/raft pathway in the regulation of mGluR trafficking in neurons.

Our findings in the present study that mGluR1/5 associates with both raft and nonraft membrane domains in neurons and heterologous cells are consistent with findings of others that exogenous mGluR5 internalizes via a clathrin-independent pathway in hippocampal neurons in culture (Fourgeaud et al., 2003). Our findings extend this observation in that we demonstrate a role for caveolin-1 in regulation of group I mGluR trafficking and signaling and identify the caveolar/raft pathway as a portal for agonist-independent cell entry of group I mGluRs in the brain. We propose a model whereby, under basal conditions, a subset of mGluR1 and -5 associates with membrane rafts and undergoes endocytosis via the caveolar/raft pathway. In rafts containing caveolin-1, binding of caveolin to mGluRs slows receptor internalization, thereby stabilizing receptors at the cell surface. Although not addressed by the present study, it is possible that neuronal activity and/or phosphorylation events could release caveolin-1 from mGluRs, thereby speeding receptor internalization and reducing the available pool of functional receptors at the cell surface. Accordingly, a functional screening of the kinome has revealed that clathrin- and caveolar/raft-dependent endocytosis are differentially regulated by kinases (Pelkmans et al., 2005). Future studies will be necessary to identify signaling molecules involved in regulation of mGluR1/5 internalization via the caveolar/lipid rafts.

Our finding that mGluRs colocalize with caveolin-1 and cholera toxin B in internalized intracellular vesicles indicates that mGluRs can be sorted along the endocytic pathway together with raft components. Although it is well established that membrane receptors can internalize via the caveolar/raft pathway, how raft components and cargo are sorted along the endocytic pathway is still unclear. Internalized caveolin-1-containing vesicles can fuse with caveosomes and, transiently, with endosomes (Pelkmans et al., 2004). On fusion with other vesicular compartments, caveolar/raft-derived vesicles do not disassemble but retain their lipid and protein content (Pelkmans et al., 2004). Consistent with this, caveolin-1 and raft components are enriched in recycling endosomes (Gagescu et al., 2000). A possible scenario is that release and sorting of cargo might be dictated by the properties of the vesicular compartment with which raft-derived vesicles fuse; these properties include pH (Pelkmans et al., 2004) and enrichment in sphingolipid and cholesterol (Chatterjee et al., 2001). Given the importance of group I mGluRs in synaptic function and spine morphogenesis, regulation of group I mGluR endocytosis and surface expression by caveolar rafts represents a potentially powerful and novel mechanism to regulate synaptic efficacy.

A novel finding of the present study is the identification of consensus caveolin recognition motifs within the intracellular loops of mGluR1 and mGluR5 that mediate binding of the receptors to caveolin-1. We show that caveolin-1 interacts with mGluR1 primarily via a motif contained within the last segment of the first transmembrane (TM) domain and first intracellular loop of the receptor. In addition, mGluR1/5 possess a second putative caveolin-1 binding motif contained within i3 and the first segment of TM6. Disruption of the i1 motif has a more marked impact on caveolin-1 binding, consistent with its dominant role (and presumably higher affinity) in caveolin-1 binding. Interestingly, both motifs are required for functional regulation of the receptor by caveolin-1. Although the role of the i3 cav-1 motif is as yet unclear, it is possible that it contributes to stabilization of mGluR1/5 by caveolin-1. Consistent with this finding, the α subunit (Slo1) of the MaxiK potassium channel contains two caveolin-binding motifs (Alioua et al., 2008), only one of which is critical to caveolin-1 binding; ablation of that motif abolishes channel expression at the cell surface. In addition to mGluR1/5, several other G-protein-coupled receptors interact with and are functionally regulated by caveolin-1 (Bhatnagar et al., 2004; Allen et al., 2007). For example, the D1 dopamine receptor was recently shown to interact with caveolin-1 in the brain; disruption of a cav-1 binding motif in the D1 receptor drastically reduces receptor expression at the cell surface (Kong et al., 2007).

Our findings indicate that, whereas ∼20% of mGluR5 appears to associate with caveolin-1 as determined by coimmunoprecipitation, the extent of colocalization of mGluR5 and caveolin-1 in hippocampal neurons in culture (E18 cultures; DIV 10) is nearly complete (∼80%) as assessed by immunolabeling (Fig. 8A). There are several factors that might account for the apparent discrepancy in colocalization of mGluRs with caveolin-1 as assessed by coimmunoprecipitation versus immunolabeling. First, the interaction of mGluRs with caveolin-1 might be transient, giving rise to a low efficiency of IP. Second, in rat brain cortex under basal conditions, only a subset of mGluRs fractionates with caveolin-1, as assessed by sucrose density centrifugation, suggesting that association of mGluRs with rafts may be regulated by activity as shown for other receptors (Kong et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2008). Third, whereas the fractionation and IP experiments were performed with adult rat hippocampal lysates, the colocalization experiments were performed with “young” (DIV 10) hippocampal neurons in culture.

Caveolin-1 is expressed in neurons in several brain regions (Galbiati et al., 1998), including hippocampus (Petralia et al., 2003) and hypothalamus (Zschocke et al., 2002). Ultrastructural analysis indicates that caveolin-1 is present at excitatory synapses, at which it becomes concentrated in the postsynaptic density late in development (Petralia et al., 2003). Our finding that only a fraction of mGluR5 associates with caveolin-1 in the brain, suggests the possibility that interaction of the receptors with caveolin-1 might be transient and spatially restricted. Caveolin-1 is a “multitasking” protein that participates in lipid and protein trafficking and regulates signal transduction. Although little is known concerning the function(s) of caveolin-1 in neurons, one of its established functions in non-neuronal cells is to regulate the activity of signaling proteins that reside in caveolae (Okamoto et al., 1998). For example, caveolin-1 regulates ERα (estrogen receptor α) signaling to mGluR1 in hippocampal neurons (Boulware et al., 2007) and is critical for NMDA receptor-dependent activation of Src and ERK1/2 in cortical neurons (Head et al., 2008). Our findings indicate that, in HEK293 cells, caveolin-1 overexpression not only attenuates constitutive mGluR1 endocytosis but also decreases mGluR1-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in response to stimulation with glutamate. Given the short time of exposure to agonist (≤5 min), the observed decrease in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the presence of cotransfected caveolin-1 is likely unrelated to receptor desensitization via endocytosis, although the present study does not directly address the function of caveolin-1 in agonist-dependent mGluR internalization. Our observation is consistent with findings of enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Cav-1−/− neurons under basal conditions (Head et al., 2008) and dysregulation of ERK–MAPK signaling in caveolin-1 knock-out mice (Cohen et al., 2003). In neurons, the enhanced ERK–MAPK signaling observed in the absence of caveolin-1 under basal conditions may occlude at least in part mGluR-dependent stimulation of this pathway. Caveolin-1 could modulate neurotransmission by modifying the function/signaling properties of its binding partners such as nNOS (neuronal nitric oxide synthase), PKCα, and adenylyl cyclase (Liu et al., 2002), or by modulating the efficacy of glutamate receptor signaling. mGluR1/5- and protein synthesis-dependent hippocampal LTD requires activation of ERK–MAPK (Gallagher et al., 2004). Importantly, mGluR1/5-dependent LTD is exaggerated in Fmr1 knock-out mice, implicating dysregulation of group I mGluR signaling in the cognitive deficits underlying fragile X (Bear et al., 2004). Thus, by modulating mGluR1/5 signaling to downstream effectors, caveolin-1 may contribute to regulation of synaptic efficacy. The impact of caveolin-1 on neuronal signaling may become prominent in pathological situations in which its expression is dysregulated, such as neuronal injury (Gaudreault et al., 2005), ischemia (Shen et al., 2006), and Alzheimer's disease (Gaudreault et al., 2004).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (A.F.), FRAXA (A.F.), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants NS47684 (A.F.) and NS20752 (R.S.Z.). R.S.Z. is the F. M. Kirby Professor in Neural Repair and Protection. We thank Dr. Robert Duvoisin for providing reagents, and Monique Bryan and Francesca Galasso for skilled technical assistance and image quantification. We also thank Roodland Regis and Yingjia Liu for help with brain dissections. We are grateful to the late Joe Zavilowitz for assistance with confocal microscopy. A.F. thanks Prof. M. V. L. Bennett for support, encouragement, and insightful scientific discussion.

References

- Aiba A, Chen C, Herrup K, Rosenmund C, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S. Reduced hippocampal long-term potentiation and context-specific deficit in associative learning in mGluR1 mutant mice. Cell. 1994a;79:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiba A, Kano M, Chen C, Stanton ME, Fox GD, Herrup K, Zwingman TA, Tonegawa S. Deficient cerebellar long-term depression and impaired motor learning in mGluR1 mutant mice. Cell. 1994b;79:377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alioua A, Lu R, Kumar Y, Eghbali M, Kundu P, Toro L, Stefani E. Slo1 caveolin-binding motif, a mechanism of caveolin-1-Slo1 interaction regulating Slo1 surface expression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4808–4817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JA, Halverson-Tamboli RA, Rasenick MM. Lipid raft microdomains and neurotransmitter signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:128–140. doi: 10.1038/nrn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RG. The caveolae membrane system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A, Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK, Compton-Toth B, Roth BL. Caveolin-1 interacts with 5-HT2A serotonin receptors and profoundly modulates the signaling of selected Galphaq-coupled protein receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34614–34623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV, Godin C, Anborgh PH, Dale LB, Poulter MO, Ferguson SSG. Ral and phospholipase D2-dependent pathway for constitutive metabotropic glutamate receptor endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8752–8761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3155-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MI, Kordasiewicz H, Mermelstein PG. Caveolin proteins are essential for distinct effects of membrane estrogen receptors in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9941–9950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusés JL, Chauvet N, Rutishauser U. Membrane lipid rafts are necessary for the maintenance of the α7 nicotinic acethylcholine receptor in somatic spines of ciliary neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:504–512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00504.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Smith ER, Hanada K, Stevens VL, Mayor S. GPI anchoring leads to sphingolipid-dependent retention of endocytosed proteins in the recycling endosomal compartment. EMBO J. 2001;20:1583–1592. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AW, Park DS, Woodman SE, Williams TM, Chandra M, Shirani J, Pereira de Souza A, Kitsis RN, Russell RG, Weiss LM, Tang B, Jelicks LA, Factor SM, Shtutin V, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 null mice develop cardiac hypertrophy with hyperactivation of p42/44 MAP kinase in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C457–C474. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couet J, Li S, Okamoto T, Ikezu T, Lisanti MP. Identification of peptide and protein ligands for the caveolin-scaffolding domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6525–6533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-β receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:410–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dölen G, Osterweil E, Rao BS, Smith GB, Auerbach BD, Chattarji S, Bear MF. Correction of fragile X syndrome in mice. Neuron. 2007;56:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourgeaud L, Bessis AS, Rossignol F, Pin JP, Olivo-Marin JC, Hémar A. The metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 is endocytosed by a clathrin-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12222–12230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourgeaud L, Mato S, Bouchet D, Hémar A, Worley PF, Manzoni OJ. A single in vivo exposure to cocaine abolishes endocannabinoid-mediated long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6939–6945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0671-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi A, Duvoisin RM. Alternative splicing unmasks dendritic and axonal targeting signals in metabotropic glutamate receptor 1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2196–2205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02196.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi A, Kumari R, Suzanne Zukin R. Proteomic analysis reveals novel binding partners of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1. J Neurochem. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagescu R, Demaurex N, Parton RG, Hunziker W, Huber LA, Gruenberg J. The recycling endosome of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells is a mildly acidic compartment rich in raft components. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2775–2791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati F, Volonte D, Gil O, Zanazzi G, Salzer JL, Sargiacomo M, Scherer PE, Engelman JA, Schlegel A, Parenti M, Okamoto T, Lisanti MP. Expression of caveolin-1 and -2 in differentiating PC12 cells and dorsal root ganglion neurons: caveolin-2 is up-regulated in response to cell injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10257–10262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher SM, Daly CA, Bear MF, Huber KM. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation is required for metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression in hippocampal area CA1. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4859–4864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5407-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault SB, Dea D, Poirier J. Increased caveolin-1 expression in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:753–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault SB, Blain JF, Gratton JP, Poirier J. A role for caveolin-1 in post-injury reactive neuronal plasticity. J Neurochem. 2005;92:831–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT, Klintsova AY, Irwin SA, Galvez R, Bates KE, Weiler IJ. Synaptic regulation of protein synthesis and the fragile X protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7101–7106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141145998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirland C, Suzuki S, Kojima M, Lu B, Zheng JQ. Lipid rafts mediate chemotropic guidance of nerve growth cones. Neuron. 2004;42:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan AJ, Blakemore C, Katsnelson A, Vitalis T, Huber KM, Bear M, Roder J, Kim D, Shin HS, Kind PC. PLC-β1, activated via mGluRs, mediates activity-dependent differentiation in cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:282–288. doi: 10.1038/85132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head BP, Patel HH, Tsutsumi YM, Hu Y, Mejia T, Mora RC, Insel PA, Roth DM, Drummond JC, Patel PM. Caveolin-1 expression is essential for N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-mediated Src and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation and protection of primary neurons from ischemic cell death. FASEB J. 2008;22:828–840. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9299com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering H, Lin CC, Sheng M. Lipid rafts in the maintenance of synapses, dendritic spines, and surface AMPA receptor stability. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3262–3271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03262.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans E, Challiss RA. Structural, signaling and regulatory properties of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: prototypic family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem J. 2001;359:465–484. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Kayser MS, Bear MF. Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science. 2000;288:1254–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichise T, Kano M, Hashimoto K, Yanagihara D, Nakao K, Shigemoto R, Katsuki M, Aiba A. mGluR1 in cerebellar Purkinje cells essential for long-term depression, synapse elimination, and motor coordination. Science. 2000;288:1832–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Chen G. High Ca2+-phosphate transfection efficiency in low-density neuronal cultures. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:695–700. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, Markou A. The ups and downs of addiction: role of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong MM, Hasbi A, Mattocks M, Fan T, O'Dowd BF, George SR. Regulation of D1 dopamine receptor trafficking and signaling by caveolin-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1157–1170. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Simons K, Dotti CG. Neuronal polarity: essential role of protein-lipid complexes in axonal sorting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3966–3971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Rudick M, Anderson RG. Multiple functions of caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41295–41298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi IR, Le PU. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:673–677. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Schlegel A, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Caveolins, a family of scaffolding proteins for organizing “preassembled signaling complexes” at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5419–5422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton RG, Joggerst B, Simons K. Regulated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1199–1215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel HH, Murray F, Insel PA. G-protein-coupled receptor-signaling components in membrane raft and caveolae microdomains. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;186:167–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72843-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Lavezzari G, Racca C, Roche KW, McBain CJ. mGluR7 is a metaplastic switch controlling bidirectional plasticity of feedforward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;46:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans L, Bürli T, Zerial M, Helenius A. Caveolin-stabilized membrane domains as multifunctional transport and sorting devices in endocytic membrane traffic. Cell. 2004;118:767–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans L, Fava E, Grabner H, Hannus M, Habermann B, Krausz E, Zerial M. Genome-wide analysis of human kinases in clathrin- and caveolae/raft-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2005;436:78–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wang YX, Wenthold RJ. Internalization at glutamatergic synapses during development. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3207–3217. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodal SK, Skretting G, Garred O, Vilhardt F, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:961–974. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Ma S, Chan P, Lee W, Fung PC, Cheung RT, Tong Y, Liu KJ. Nitric oxide down-regulates caveolin-1 expression in rat brains during focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1078–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]