Abstract

PURPOSE

The transactivator protein Tat encoded by the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) genome reduces glutathione levels in mammalian cells. Because the retina contains large amounts of glutathione, a study was undertaken to determine the influence of Tat on glutathione levels, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity, and the expression and activity of the cystineglutamate transporter xc- in the human retinal pigment epithelial cell line ARPE-19 and in retina from Tat-transgenic mice.

METHODS

The transport function of xc- was measured as glutamate uptake in the absence of Na+. mRNA levels for xCT and 4F2hc, the two subunits of system xc-, were monitored by RT-PCR and Northern blot and protein levels by Western blot. The expression pattern of xCT and 4F2hc in the mouse retina was analyzed by immunofluorescence.

RESULTS

Expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells led to a decrease in glutathione levels and an increase in γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. The transport function of xc- was upregulated, and this increase was accompanied by increases in the levels of mRNAs for xCT and 4F2hc and in corresponding protein levels. The influence of Tat on the expression of xc- was independent of the cellular status of glutathione. Most of these findings were confirmed in the retina of Tat-transgenic mice.

CONCLUSIONS

Expression of HIV-1 Tat in the retina decreases glutathione levels and increases γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. Tat also upregulates the expression of system xc-. Glutathione levels may be decreased and the expression of xc- enhanced in the retina of patients with HIV-1 infection, leading to oxidative stress and excitotoxicity.

Cystine-glutamate transporter, known as xc-, mediates the Na+-independent, electroneutral exchange of cystine and glutamate.1,2 Under physiological conditions, xc- transports cystine into the cells coupled to the efflux of intracellular glutamate. This transport system plays a critical role in glutathione homeostasis, because cellular synthesis of glutathione is limited by intracellular levels of cysteine. The transport system xc- supplies cells with this rate-limiting amino acid. Cystine transported into cells by xc- is effectively reduced to cysteine for cellular utilization. Glutathione is an essential antioxidant necessary for protection of the cells against oxidative damage, and therefore xc- assumes significance as a transport system closely associated with the cellular antioxidant machinery. xc- is a heterodimeric transporter, consisting of a light chain and a heavy chain.3,4 The heavy chain is known as 4F2hc and the light chain as xCT. The light chain has been cloned from mouse and human tissues.5–9 The relevance of this transport system to cellular antioxidant processes is highlighted by the observations that cells exposed to oxidative stress upregulate this transport system. This has been shown in a variety of cell and tissue types, including macrophages,10 retinal pigment epithelial cells,7 conjunctival epithelial cells,11 the blood– brain barrier,12 and the blood–retinal barrier.13 The transcription factor Nrf2 participates in this oxidant-induced upregulation of xc-.14,15

Recent studies16 have shown that xc- also plays a critical role in the regulation of extracellular levels of glutamate in the brain. This is not surprising, because xc- is expressed widely in the brain17 and this transport system mediates the efflux of glutamate. Thus, xc- contributes to the nonsynaptic source of extracellular glutamate in the brain. Because glutamate is an excitotoxin to neurons, increased activity of this transport system may cause excitotoxicity by elevating the extracellular levels of this amino acid. There is evidence that the transport function of xc- in the brain plays an important role in cocaine withdrawal and abuse.18 In addition, quisqualic acid is a high-affinity substrate for xc-, and it has been shown recently that transport of this compound into hippocampal neurons is a prerequisite for the induction of quisqualic acid sensitization.19

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 in humans is associated with decreased levels of glutathione in tissues and in circulation.20,21 Because glutathione not only participates as an antioxidant but also is important for conjugation of various drugs and xenobiotics necessary for their subsequent elimination from the body, glutathione deficiency in HIV-1 infection contributes to the oxidative damage as well as drug toxicity often associated with the infection.22–24 There is evidence to indicate that the HIV-1–induced decrease in glutathione levels in host cells may provide an advantage to the virus for enhanced proliferation.25,26 There are also data to show that the decrease in glutathione levels in host cells is directly related to virus infection rather than a secondary effect associated with any other pathologic consequences of virus infection.27,28 The influence of HIV-1 infection on glutathione levels in infected cells appears to be caused primarily by Tat, a transactivator protein coded by the HIV-1 genome.29–31 Recent studies by Choi et al.30 have shown that the expression of Tat in mice leads to downregulation of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of glutathione. This enzyme consists of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit.32 It is the regulatory subunit that is down-regulated in Tat-transgenic mice with no change in the expression of the catalytic subunit.30

The present investigation was undertaken to investigate the role of xc- in the Tat-induced decrease of glutathione levels. Ocular tissues, especially the retinal pigment epithelium, contain high levels of glutathione, which is necessary to prevent tissue damage that may otherwise be caused by photo-oxidation.33 The present investigation was performed first with control and Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells to assess the influence of Tat on the expression and activity of xc- in this cell line. Subsequently, the results were confirmed with retinas from Tat-transgenic mice.

METHODS

Materials

The Tat cDNA construct in pGEM2 vector (catalog no. 909) and the monoclonal antibody specific for Tat (catalog no. 4138) were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Rockville, MD). The human RPE cell line ARPE-19 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The polyclonal antibody against 4F2hc, raised in the rabbit, was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). This antibody recognizes mouse and human 4F2hc. The polyclonal antibody against xCT was generated in the rabbit using the antigenic peptide MVRKPVVATISKGGY, which corresponds to the amino acid sequence 1-15 in mouse xCT. This antibody also recognizes human xCT. The secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG), labeled with Cy-3 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Chester, PA). The pDOI-5 vector, used in the generation of transgenic mice with targeted expression of the transgene in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II–positive cells, was kindly provided by Diane J. Mathis (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA).

[3H]-Glutamate (sp. radioactivity, 38.5 Ci/mmol), [3H]-leucine (sp. radioactivity, 60 Ci/mmol), [3H]-alanine (sp. radioactivity, 40 Ci/mmol), [3H]-arginine (sp. radioactivity, 57 Ci/mmol), and [3H]-tryptophan (sp. radioactivity, 29 Ci/mmol) were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc. (Boston, MA).

Stable Transfection of ARPE-19 Cells with pcDNA-Tat cDNA

The pGEM2-Tat cDNA construct contained as the insert a 295-bp fragment encoding the first exon of Tat gene joined to a 145-bp pET3A transcription terminator. The entire insert (440 bp) was removed from the construct by digestion with PstI and EcoRI and ligated into the multiple cloning region of the pcDNA3.1(—) vector at the PstI–EcoRI site, so that the insert was downstream of the CMV promoter. The resultant construct was sequenced to confirm the orientation of the insert. This construct was electroporated into ARPE-19 cells, and the stably transfected cell clones were isolated in the presence of geneticin (G418). To serve as a control, empty pcDNA3.1 vector was electropo-rated into ARPE-19 cells in an identical manner, and the clones harboring the vector were selected by G418 resistance.

The expression of Tat in the stably transfected cell line (Tat-ARPE-19) was confirmed by the analysis of Tat mRNA and Tat protein. Total RNA was isolated from control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells and used as the template for RT-PCR to monitor the expression of Tat mRNA. The primers used for RT-PCR were: 5′-GTCAACATAGCAGAATAGGCAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTACCCATCCGGATATAGTTC-3′ (anti-sense). These primers encompassed the entire insert in the pcDNA-Tat construct, and the expected size of the RT-PCR product was 441 bp. The expression of the Tat protein in the stably transfected cell line was monitored by immunofluorescence using a monoclonal antibody specific for Tat. The Tat-ARPE-19 cell line shows the expression of Tat at the mRNA level as well as at the protein level.34

Uptake Measurements in Control ARPE-19 Cells and Tat-ARPE-19 Cells

Control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells were maintained in 75-cm2 culture flasks in DMEM/F-12 medium in the presence of fetal bovine serum (10%) and G418 (100 μg/mL). For uptake measurements, cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates at an initial density of 0.1 × 106 cells/well. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium on the second day after the initial seeding, and uptake measurements were made on the third day. The transport function of system xc- was monitored as the Na+-independent uptake of [3H]-glutamate, as described previously.7 Saturation kinetics was analyzed by fitting the data to Michaelis-Menten equation. The Michaelis-Menten constant (Kt) was calculated by nonlinear regression analysis and then confirmed by linear regression. Experiments were repeated three times, and the results are expressed as the mean ± SE.

Influence of Glutathione Supplementation and Glutathione Depletion on xc- Activity

Control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells were cultured for 48 hours in control medium, in medium supplemented with 2 mM glutathione, and in medium containing 0.2 mM buthionine sulfoximine, an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis. The transport activity of system xc- was then measured in these cells.

Measurement of γ-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity and Cellular Levels of Glutathione

The activity of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells was measured with cell homogenates using γ-glutamyl p-nitroanilide as described previously.35,36 Cellular levels of glutathione were measured using a commercially available kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA).

Northern Blot Analysis

The steady state levels of xCT mRNA and 4F2hc mRNA in control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells were analyzed by Northern blot using [32P]-labeled cDNA probes specific for human xCT7 and human 4F2hc.37 Poly(A)+ RNA isolated from confluent cultures of control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells was used in this analysis. To correct for potential variations in RNA loading, we first used glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA as an internal control. But, we found that Tat expression in these cells increased the steady state levels of this mRNA markedly. Therefore, this mRNA was unsuitable as an internal control. Although screening for the activities of various transporters in control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells, we found that carnitine transport was not affected by Tat expression in these cells. Therefore, we used the mRNA specific for the carnitine transporter (OCTN2)38 as the internal control in Northern blot analysis.

Western Blot Analysis of xCT Protein and 4F2hc Protein in Control ARPE-19 Cells and in Tat-ARPE-19 Cells

The expression of xCT protein and 4F2hc protein in control cells and in Tat-expressing cells were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies specific for xCT and 4F2hc. The antibody-specific bands were detected using chemiluminescence (Enhanced ChemiLuminescence kit; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc.). The constitutively expressed ERK2 was used as an internal control in Western analysis to correct for differences in protein loading in different lanes.

Generation of Tat-Transgenic Mouse

We generated a Tat-transgenic mouse in which the expression of the transgene was restricted to MHC class II–positive immune cells (macrophages, B cells, and dendritic cells), by using a targeting construct derived from a vector (pDOI-5) used for the expression of foreign cDNAs in the MHC class II–positive cells of transgenic mice.39 This vector contains a fragment of the rabbit β-globin gene that provides an intron as well as a polyadenylation signal to aid the export of the transgene transcript from the nucleus and also to stabilize the transcript. The transgene is inserted into this vector in the middle of the rabbit β-globin gene so that the expression of the transgene is driven by the promoter of the murine MHC class II gene Ea, placed upstream of the rabbit β-globin gene. The construct was sequenced to identify the clone in which the transgene was in the right orientation so that its expression was under the control of the promoter Ea gene. This targeting construct was used to generate the transgenic mouse line.

Analysis of the Expression of Tat mRNA and Protein in Transgenic Mouse

The transgenic mouse line was genotyped by PCR, using genomic DNA and primers specific for the targeting vector. The sense primer (5′-GTCAACATAGCAGAATAGGCAT-3′) was located at the beginning of the Tat gene insert in the vector and the antisense primer (5′-GGCTTCATGATGTCCCCATAAT-3′) was located downstream of the transgene in the rabbit β-globin gene. The predicted size of the PCR product was 566 bp. The expression of Tat mRNA was assessed by RT-PCR using primers specific for Tat and total RNA isolated from tissues. The expression of Tat protein was analyzed in macrophages by Western blot, using a monoclonal antibody specific for Tat. The chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc.) was used for detection. Macrophages were isolated from peritoneal lavage 5 days after intraperito-neal injection with autoclaved Brewers thioglycollate broth. Cells were harvested from the peritoneal lavage, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and cultured in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium, supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and 10% fetal bovine serum. Nonadherent cells were removed by gentle washing of the culture wells. The adhered macrophages were then collected to prepare cell lysates for Western blot analysis.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR for the Comparative Analysis of the Expression of mRNAs for xCT, 4F2hc, and Heavy and Light Subunits of γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase between Retina from Control Mice and Tat-Transgenic Mice

We used the commercially available kit (Competimer QuantumRNA; Ambion, Austin, CT) for the determination of the relative levels of mRNAs for xCT, 4F2hc, and heavy and light subunits of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase in RPE-eyecups from control mice and Tat-transgenic mice. Total RNA was prepared from the RPE-eyecups and used for this purpose. The kit uses 18S RNA as the internal standard and the Competimer technology to modulate the amplification efficiency of a PCR template without affecting the performance of other targets in a multiplex PCR. The PCR products were size fractionated on agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The intensities of 18S RNA bands and target mRNA bands were quantified on computer (Image-QuaNT, ver. 4.2a; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). For each RNA sample, the signal obtained for the amplicon of the target RNA was divided by the signal obtained for the 18S RNA amplicon. This yielded a corrected relative value for the target RNA in each sample. These values were used for comparison of the steady state levels of mRNAs for xCT, 4F2hc, and heavy and light subunits of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase in RPE-eyecups between control mice and Tat-transgenic mice. The RPE-eyecups were prepared from control and Tat-transgenic mice as described previously.40 After are the primers used for RT-PCR: 5′-CTCCATCATCATCGGCACCGTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGCAGCAGCTCCTCCGCACTGA-3′ (antisense) for mouse xCT (product size, 747 bp), 5′-GGCGCCGTGGTTATCATCGTTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCGCTGGTGGATTCAAGTATGT-3′ (antisense) for mouse 4F2hc (product size, 599 bp), 5′-CAACACTGTGGAGGCCAATATGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCTCTCCTCCCGTGTTCTATCATC-3′ (antisense) for the heavy subunit of mouse γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (product size, 586 bp), and 5′-TGACATGGCATGCTCCGTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGGGTGTGAGCTGGAGTTAAGAG-3′ (antisense) for the light subunit of mouse γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (product size, 513 bp).

The animals were treated in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Localization of xCT and 4F2hc in Retina by Immunofluorescence

Frozen sections of mouse retina were first incubated with the primary antibodies specific for xCT or 4F2hc. Negative control experiments were performed by blocking the anti-xCT antibody with 20 μg/mL of the antigenic peptide for 30 minutes before incubation with tissue sections. In the case of 4F2hc, negative control experiments were performed by incubating the tissue sections without the primary antibody. Detection of the antibody-specific signals were performed by immunofluorescence, using Cy-3– conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for xCT and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 4F2hc.

RESULTS

Influence of Tat on Cellular Levels of Glutathione and γ-Glutamyl Transpeptidase in ARPE-19 Cells

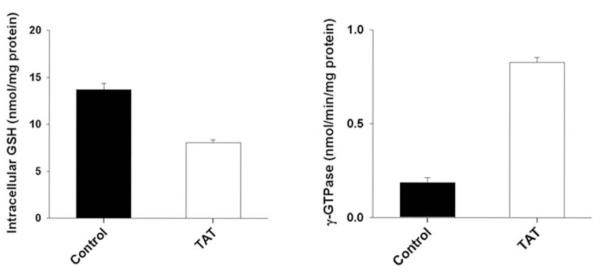

We first measured the levels of glutathione in control ARPE-19 cells and in Tat-ARPE-19 cells. These studies showed that the cellular levels of glutathione were reduced by 45% in Tat-ARPE-19 cells compared with control ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 1). We then measured the activity of the plasma membrane enzyme γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in these cells to determine whether the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells influences the activity of this enzyme. This enzyme is responsible for the hydrolysis of extracellular glutathione. We found that the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells markedly upregulates the activity of this enzyme (Fig. 1). The activity of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in Tat-ARPE-19 cells was four times higher than in control ARPE-19 cells.

Figure 1.

Influence of Tat on glutathione levels and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity in ARPE-19 cells. Cellular levels of glutathione were measured in control ARPE-19 cells (Control) and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (TAT). Corresponding cell homogenates were used to measure the activity of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTPase).

Transport Activity of xc- in Control ARPE-19 Cells and in Tat-ARPE-19 Cells

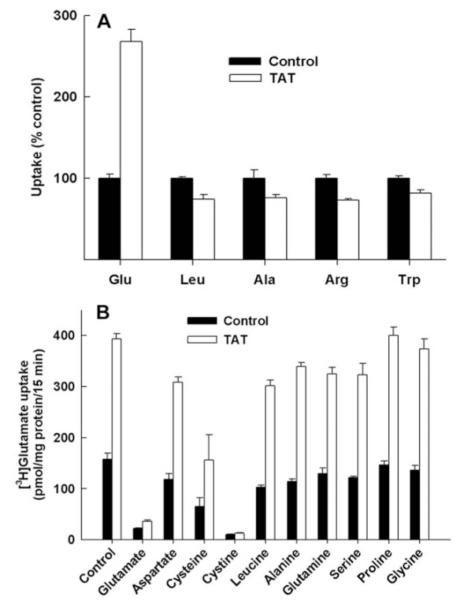

We then measured the transport function of xc- in control and Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells. Because xc- is a cystine-gluta-mate exchanger, the transport activity of this system can be monitored not only as the Na+-independent uptake of [35S]-cystine, in which case the system mediates the cellular uptake of [35S]-cystine in exchange for intracellular glutamate, but also as the Na+-independent uptake of [3H]-glutamate, in which case the system mediates the cellular uptake of [3H]-glutamate in exchange for unlabeled glutamate from inside the cells. We routinely prefer to use the latter approach for the measurement of xc- activity because of the unstable nature of 35S radiolabel. Thus, xc-, which catalyzes cystine-glutamate exchange under physiological conditions, mediates glutamateglutamate exchange under the experimental conditions. Furthermore, because the measurements were made in the absence of Na+, there was no contribution to glutamate uptake by any of the members of the EAAT family, which are Na+- coupled glutamate transporters. The results of these studies showed that the transport activity of xc- did not decrease as a result of Tat expression as we originally hypothesized but increased markedly. The uptake of glutamate in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells was 2.7-fold higher than in control ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 2A). This effect was specific because the uptake of leucine, alanine, arginine, and tryptophan was not altered in the cells due to Tat expression when measured under identical conditions. Substrate specificity studies showed that the up-take of [3H]-glutamate in control cells and in Tat-expressing cells was completely inhibited only by unlabeled glutamate and cystine (Fig. 2B). Cysteine inhibited the uptake but to a much lesser extent. Other amino acids tested (aspartate, leucine, alanine, glutamine, serine, proline, and glycine) did not have any effect on [3H]-glutamate uptake. Moreover, the Tat-induced increase in [3H]-glutamate in these cells was completely abolished when measured in the presence of excess amount of unlabeled glutamate and cystine.

Figure 2.

Influence of Tat on the activity of system xc-. (A) The transport activity of system xc- was measured in control ARPE-19 cells (Control) and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (TAT) by determining the uptake of [3H]-glutamate (5 μM) with 15 minutes incubation in the absence of Na+. The specificity of Tat effect on system xc- was investigated by measuring the uptake, under identical conditions, of four other amino acids (leucine, alanine, arginine, and tryptophan) whose uptake is not mediated by system xc-. The concentration of these amino acids during uptake was 5 μM. (B) The substrate specificity of the glutamate uptake process that was induced by Tat was investigated by assessing the influence of various unlabeled amino acids (2.5 mM) on the uptake of [3H]-glutamate (5 μM) in control ARPE-19 cells (Control) and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (TAT).

Kinetic Analysis of xc- in Control ARPE-19 Cells and in Tat-ARPE-19 Cells

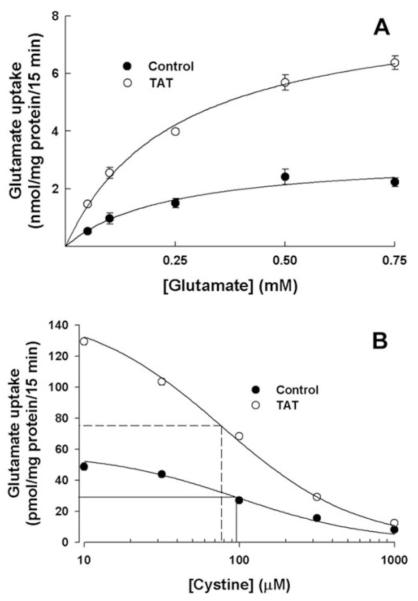

The uptake of glutamate was saturable in control cells as well as in Tat-expressing cells (Fig. 3A). The Michaelis-Menten constant (Kt) was not found to be influenced by Tat expression. The Kt in control ARPE-19 cells and in Tat-ARPE-19 cells were 230 ± 20 and 215 ± 15 μM, respectively. However, the value for the maximal velocity (Vmax) increased 2.6-fold in Tat-expressing cells compared with control cells (8.3 ± 0.3 vs. 3.1 ± 0.2 nmol/mg of protein/15 minutes, respectively). Because xc- mediates the influx of cystine under physiological conditions and it is the entry of this amino acid into cells that is functionally related to glutathione synthesis, it was necessary to evaluate the Kt value for this amino acid in control cells and in Tat-expressing cells. The evaluation was performed by using cystine as a competitor for [3H]-glutamate for uptake through xc- and determining the IC50 (i.e., the concentration of cystine necessary for half-maximum inhibition of glutamate uptake). The IC50 is an indirect measure of the affinity of the transport system for cystine. These studies showed that the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells did not have any significant effect on the IC50 (98 ± 17 μM in control cells and 77 ± 6 μM in Tat-expressing cells; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Kinetic analysis of system xc- in control ARPE-19 cells and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells. (A) Uptake of glutamate was measured in control ARPE-19 cells and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells over a concentration range of 0.05 to 0.75 mM with 15 minutes incubation in the absence of Na+. (B) Uptake of [3H]-glutamate (2 μM) was measured in control ARPE-19 cells and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells with 15 minutes incubation in the absence of Na+ but in the presence of increasing concentrations of cystine.

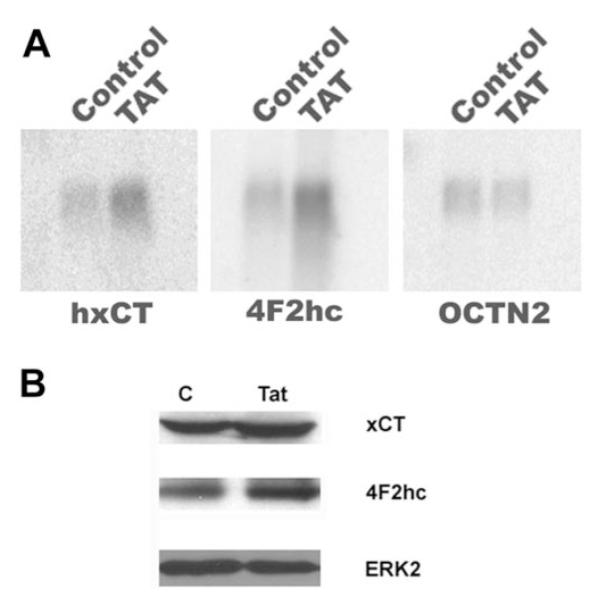

Influence of Tat on the Steady State Levels of xCT mRNA and 4F2hc mRNA and the Respective Proteins

Northern blot analysis showed that the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells increased the steady state levels of mRNAs for xCT and 4F2hc (Fig. 4A). After correction for differences in RNA loading using OCTN2 mRNA signals as the internal control, the Tat-induced increase in steady state mRNA levels was 3-fold for xCT and 2.7-fold for 4F2hc. The protein levels of xCT and 4F2hc were also increased by twofold in Tat-ARPE-19 cells compared with control cells, as detected by Western analysis (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of Tat on the steady state mRNA and protein levels of xCT and 4F2hc. (A) Northern blot analysis of steady state levels of mRNA for xCT and 4F2hc in control ARPE-19 cells (Control) and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (TAT). The same blot was analyzed for OCTN2 mRNA as an internal control. (B) Western blot analysis of xCT and 4F2hc protein levels in control ARPE-19 cells (C) and in Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (Tat). The same blot was analyzed for ERK2 protein levels as an internal control.

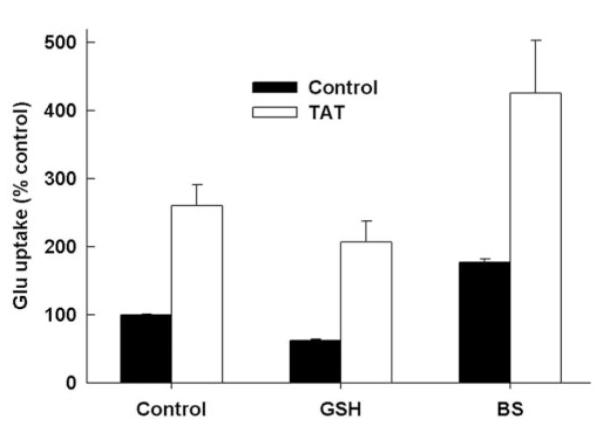

Relevance of Glutathione to Tat-Induced Upregulation of System xc- Expression

We then investigated the influence of glutathione on Tat-induced upregulation of system xc- expression. We first cultured the control ARPE-19 cells and Tat-ARPE-19 cells in the presence of 2 mM glutathione for 2 days and then measured the transport activity of xc- (Fig. 5). Glutathione supplementation decreased the activity of system xc- in control cells and in Tat-expressing cells. However, the Tat-induced upregulation of xc- was maintained in the absence and presence of glutathione. We then investigated the effect of glutathione depletion on Tat-induced upregulation of xc- by culturing the control cells and the Tat-expressing cells in the presence of 0.2 mM buthionine sulfoximine, a specific inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase. The depletion of cellular glutathione by this maneuver increased the activity of system xc- in control cells as well as in Tat-expressing cells (Fig. 5). This showed that oxidative stress caused by glutathione depletion indeed induces xc- activity. However, there was no change in the influence of Tat on the expression and activity of system xc-. Even in the presence of buthionine sulfoximine, the expression of Tat led to a 2.3 ± 0.1-fold increase in xc- activity.

Figure 5.

Influence of Tat on system xc- activity under conditions of glutathione supplementation and glutathione depletion. Control ARPE-19 cells (Control) and Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells (TAT) were cultured for 2 days in the absence or presence of 2 mM glutathione (GSH) or 0.2 mM buthionine sulfoximine (BS). Uptake of [3H]-gluta-mate (5 μM) was then measured in these cells with 15 minutes of incubation in the absence of Na+. Uptake measured in control ARPE-19 cells under normal culture conditions was taken as 100%.

Influence of Tat on the Expression of xCT, 4F2hc, and Heavy and Light Subunits of γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase in Transgenic Mice

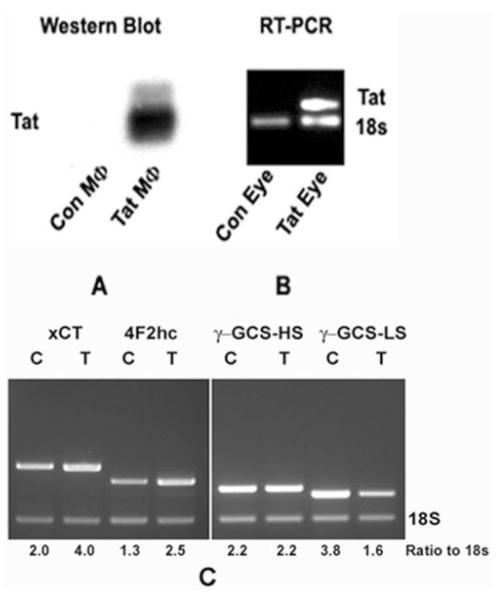

To determine whether Tat has similar effects on the expression of xc- in intact animals, we used Tat-transgenic mice. The expression of Tat protein was detectable in macrophages of this mouse line (Fig. 6A). The expression of Tat mRNA was detectable by RT-PCR in ocular tissues of the transgenic mice, most likely from the RNA derived from the Tat-expressing immune cells present in the ocular tissues (Fig. 6B). When we analyzed the steady state levels of xCT mRNA and 4F2hc mRNA in RPE-eyecups obtained from the transgenic mice, we found that the steady state levels of xCT and 4F2hc mRNAs were increased approximately twofold in the Tat-expressing mice compared with control mice (Fig. 6C). We also evaluated the expression of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of glutathione, in RPE-eyecups obtained from control and Tat-transgenic mice (Fig. 6C). There was no change in the steady state levels of mRNA for the heavy subunit between control and Tat-transgenic mice, but the steady state levels of mRNA for the light subunit were decreased by 60% in Tat-transgenic mice compared with control mice.

Figure 6.

Steady state levels of 4F2hc mRNA and xCT mRNA in control mice and in Tat-transgenic mice. (A) The expression of the transgene Tat in Tat-transgenic mice was demonstrated by the detection of the Tat protein (Western blot) in macrophages isolated from the Tat-transgenic mice (Tat MΦ). Macrophages isolated from control mice (Con MΦ) were negative for the transgene protein product. (B) The expression of Tat mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from whole eyes (Con Eye, eyes from control mice; Tat Eye, eyes from Tat-transgenic mice). 18S RNA was analyzed in the same RNA samples as internal control. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR for the analysis of steady state levels of mRNAs for 4F2hc, xCT, and heavy and light subunits of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS-HS and γ-GCSLS) in control RPE-eyecups (C) and in transgenic RPE-eyecups (T). 18S RNA was analyzed in the same RNA samples as the internal control.

RPE Glutathione Levels in Control Mice and Tat-Transgenic Mice

We determined the levels of glutathione in RPE-eyecups obtained from control mice and Tat-transgenic mice. There was a significant decrease in the levels of glutathione in the RPE of Tat-transgenic mice compared with control mice (control mice, 80.1 ± 4.5 nmol/mg protein; Tat-transgenic mice, 65.5 ± 0.4 nmol/mg protein, P < 0.05).

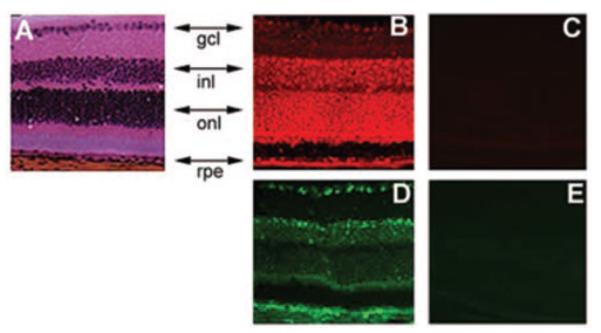

Expression Pattern of xCT and 4F2hc in Mouse Retina

We performed immunofluorescent localization studies to evaluate the expression pattern of xCT and 4F2hc in mouse retina. These studies showed both subunits of xc- to be expressed widely in retinal cells (Fig. 7). The expression is evident in the retinal pigment epithelium, outer nuclear layer consisting of photoreceptor cells, inner nuclear layer consisting of Müller cells, and neuronal cells (bipolar, amacrine, and horizontal cells), and the layer of retinal ganglion cells.

Figure 7.

Immunolocalization of the two subunits of system xc- (xCT and 4F2hc) in mouse retina. Retinal sections were probed with antibodies specific for each of these subunits. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (B) Expression pattern of xCT as detected by Cy-3–conjugated secondary antibody (red fluorescence). (C) Negative control for xCT expression where the primary antibody was first neutralized with excess antigenic peptide and then used for incubation with retinal sections. (D) Expression pattern of 4F2hc as detected by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green fluorescence). (E) Negative control experiment for 4F2hc expression, in which the primary antibody was omitted. rpe, retinal pigment epithelium; onl, outer nuclear layer consisting of photoreceptor cells; inl, inner nuclear layer consisting of Müller cells, and neuronal cells (bipolar, amacrine, and horizontal cells); gcl, ganglion cell layer.

DISCUSSION

The expression of Tat in mammalian cells and in transgenic mice has been shown to reduce the levels of glutathione.29–31 There have been no studies reported in the literature on the influence of Tat on glutathione homeostasis in the retina. Our studies showed for the first time that expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells leads to a significant decrease in glutathione levels. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase is also an essential enzyme in glutathione metabolism.41 This is a cell surface enzyme that plays a role in the hydrolysis of extracellular glutathione. The influence of Tat on this enzyme has never been studied. This prompted us to examine the influence of Tat on the expression and activity of this enzyme in ARPE-19 cells. Our data showed that γ-glutamyl transpeptidase was upregulated by Tat in these cells. Studies by other investigators have shown that γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of glutathione, is downregulated in the liver of Tattransgenic mice and that the Tat-dependent downregulation is specific for the catalytic subunit (light subunit) of the enzyme.30 In the present study, we showed for the first time that the expression of this enzyme is downregulated in the retina from Tat-transgenic mice. As demonstrated in the liver by Choi et al.,30 it is the light subunit of the enzyme that is affected by Tat in retina also. These studies suggest that the expression of Tat in transgenic mice leads to a decrease of both intracellular and extracellular glutathione levels. The downregulation of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase is expected to decrease the synthesis of glutathione, and the upregulation of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase is expected to enhance the breakdown of extracellular glutathione. Together, these changes caused by Tat in the expression of these two critical enzymes contribute to the depletion of glutathione caused by Tat.

Our initial hypothesis was that, because the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells decreased the cellular levels of glutathione, the Tat-expressing ARPE-19 cells would exhibit decreased expression and activity of the transport system xc-. The rationale for this hypothesis was as follows. The transport system xc- supplies the cells with rate-limiting amino acid cysteine for glutathione synthesis and therefore the Tat-induced decrease in glutathione levels may involve the downregulation of xc- to limit the availability of the precursor amino acid cysteine. But our studies produced unexpected results. The activity of system xc- was not downregulated by Tat as we initially hypothesized, but was upregulated. Kinetic analyses showed that Tat-induced upregulation of system xc- was associated with an increase in the maximum velocity without any significant change in the substrate affinity. These findings were supported by parallel changes in the steady state levels of mRNA and protein of the two subunits that constitute the functional system xc-: 4F2hc and xCT.

Our studies thus showed clearly that the expression of Tat in ARPE-19 cells decreased the cellular levels of glutathione, whereas the expression and activity of system xc- were up-regulated by Tat. Obviously, the decrease in glutathione levels caused by Tat was not due to the Tat-induced changes in xc- expression. The downregulation of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase activity and the upregulation of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity described in the present study most likely provide the molecular basis for the Tat-induced depletion of glutathione. Then, the question arises as to whether the decrease in glutathione levels caused by Tat expression is responsible for the upregulation of system xc-. There is unequivocal evidence for the upregulation of xc- by oxidative stress in a variety of experimental model systems.7,10–13 Therefore, it is possible that a Tat-induced decrease in glutathione levels in ARPE-19 cells causes oxidative stress that in turn leads to the upregulation of system xc- as a cellular response to oxidative stress in an attempt to increase glutathione synthesis. If this is indeed the case, glutathione supplementation and glutathione depletion should influence the effect of Tat on xc- expression, but this was not the case. Glutathione supplementation did decrease and glutathione depletion did increase the activity of system xc-, but the upregulation caused by Tat was not influenced by the glutathione supplementation or glutathione depletion. Therefore, the Tat-induced upregulation of the expression and activity of system xc- is independent of the glutathione status of the cell.

We confirmed the upregulation of system xc- by Tat observed in ARPE-19 cells in a transgenic mouse model. In these transgenic mice, the Tat protein is expressed exclusively in MHC class II–positive cells. This mouse model is a close approximation of HIV-1 infection in humans based on the similarity of the tissue distribution of Tat expression. In ARPE-19 cells stably expressing Tat, we found an upregulation of xCT as well as 4F2hc. The results were similar in Tat-transgenic mice when the expression of xCT and 4F2hc was analyzed in RPE-eyecups. Our data showed that both subunits of system xc- were expressed widely in the retina. Therefore, we conclude that the increase in the expression of xc- in the ocular tissues of the Tat-transgenic mice occur snot only in RPE cells but also in other cell types within the retina.

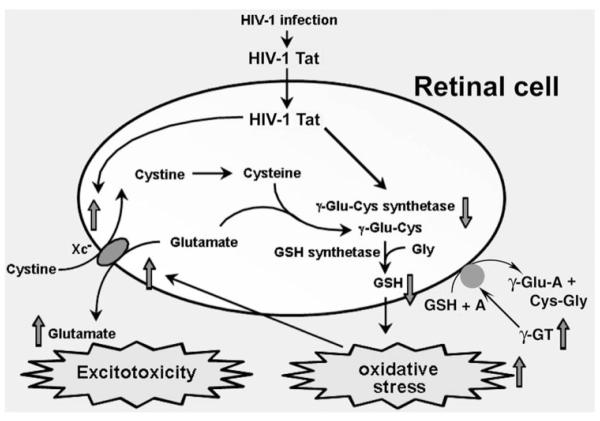

Based on these findings, we propose a model to describe the molecular events involved in the initiation of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity in the retina by Tat (Fig. 8). We speculate that the observations made in the ARPE-19 cell line with respect to the effects of Tat are applicable to most retinal cell types such as the Müller cells and ganglion cells. These cells are exposed to Tat present in the circulation in individuals infected with HIV-1. It has been shown that exposure of mammalian cells to recombinant Tat in the extracellular medium leads to changes in gene expression, indicating Tat’s ability to enter these cells to produce its biological effects.29 Tat reduces the endogenous synthesis of glutathione in the cells by down-regulating the expression of the rate-limiting enzyme γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase. It also reduces the levels of glutathione by upregulating the membrane-bound extracellular enzyme γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. This results in oxidative stress. In addition, Tat upregulates the expression of xc-, which enhances the release of glutamate into the extracellular space in the retina. This causes excitotoxicity. Our previous studies have shown that in vivo exposure of retina in mice to elevated levels of glutamate leads to apoptotic cell death in the retinal ganglion cell layer.42 We speculate that the findings of the present study may underlie the pathogenesis of noninfectious AIDS retinopathy, the most commonly observed visual condition in patients with AIDS.43–46 Noninfectious AIDS retinopathy is associated solely with the primary pathogen HIV-1 and is distinct from infectious retinopathy in AIDS, which is caused by opportunistic infections such as cytomegalovirus. Noninfectious AIDS retinopathy is characterized by thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer and loss of ganglion cells,47–50 functional defects involving Müller cells and neurons of the inner retina,51 as well as microangiopathy.52,53 Thus, noninfectious AIDS retinopathy leads to significant functional visual deficits.43–46 We hypothesize that the oxidative stress and excitotoxicity induced by Tat in RPE and other retinal cells play a major role in the retinal dysfunction associated with noninfectious AIDS retinopathy. However, we point out that the suggested relevance of the findings of the present study to the pathogenesis of noninfectious retinopathy remains speculative at this time. Direct demonstration of retinal disease in Tattransgenic mice at morphologic and functional levels would be crucial to establishing the clinical relevance of the present findings.

Figure 8.

A model identifying the molecular components that are involved in HIV-1 Tat-induced pathogenesis of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity in retina. GSH, glutathione; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; A, any acceptor molecule for γ-GT.

Footnotes

Disclosure: C.C. Bridges, None; H. Hu, None; S. Miyauchi, None; U.N. Siddaramappa, None; M.E. Ganapathy, None; L. Ignatowicz, None; D.M. Maddox, None; S.B. Smith, None; V. Ganapathy, None

References

- 1.Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J, Zorzano A. Molecular biology of mammalian plasma membrane amino acid transporters. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:969–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganapathy V, Inoue K, Prasad PD, Ganapathy ME. Cellular uptake of amino acids: system and regulation. In: Cynober LA, editor. Amino Acid Metabolism and Therapy in Health and Nutritional Diseases. 2nd ed CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chillaron J, Roca R, Valencia A, Zorzano A, Palacin M. Heteromeric amino acid transporters: biochemistry, genetics, and physiology. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:F995–F1018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.6.F995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanai Y, Endou H. Heterodimeric amino acid transporters: molecular biology and pathological and pharmacological relevance. Curr Drug Metab. 2001;2:339–354. doi: 10.2174/1389200013338324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato H, Tamba M, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, Okuno S, Bannai S. Molecular cloning and expression of human xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc- Antioxid Redox Sign. 2000;2:665–671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridges CC, Kekuda R, Wang H, et al. Structure, function, and regulation of human cystine/glutamate transporter in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassi MT, Gasol E, Manzoni M, et al. Identification and character-isation of human xCT that co-expresses, with 4F2 heavy chain, the amino acid transport activity system xc- Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:286–296. doi: 10.1007/s004240100537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JY, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, et al. Human cystine/glutamate transporter: cDNA cloning and upregulation by oxidative stress in glioma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1512:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato H, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, Hashimoto T, et al. Effect of oxygen on induction of the cystine transporter by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10407–10412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gukasyan HJ, Kannan R, Lee VH, Kim KJ. Regulation of L-cystine transport and intracellular GSH level by a nitric oxide donor in primary cultured rabbit conjunctival epithelial cell layers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1202–1210. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosoya K, Tomi M, Ohtsuki S, et al. Enhancement of L-cystine transport activity and its relation to xCT gene induction at the blood-brain barrier by diethyl maleate treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:225–231. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomi M, Hosoya K, Takanaga H, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T. Induction of xCT gene expression and L-cystine transport activity by diethyl maleate at the inner blood-retinal barrier. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:774–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki H, Sato H, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, et al. Electrophile response element-mediated induction of the cystine/glutamate exchange transporter gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44765–44771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih AY, Johnson DA, Wong G, et al. Coordinate regulation of glutathione biosynthesis and release by Nrf2-expressing glia potently protects neurons from oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3394–3406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03394.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker DA, Xi ZX, Shen H, Swanson CJ, Kalivas PW. The origin and neuronal function of in vivo nonsynaptic glutamate. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9134–9141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato H, Tamba M, Okuno S, et al. Distribution of cystine/glutamate exchange transporter, system xc-, in the mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8028–8033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08028.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, et al. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2002;6:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chase LA, Roon RJ, Wellman L, Beitz AZ, Koerner JF. L-Quisqualic acid transport into hippocampal neurons by a cystine-sensitive carrier is required for the induction of quisqualate sensitization. Neuroscience. 2001;106:287–301. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Droge W. Cysteine and glutathione deficiency in AIDS patients: a rationale for the treatment with N-acetyl-cysteine. Pharmacology. 1993;46:61–65. doi: 10.1159/000139029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staal FJ. Glutathione and HIV infection: reduced, or increased oxidized? Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:194–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Favier A, Sappey C, Leclerc P, Faure P, Micoud M. Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in patients infected with HIV. Chem Biol Interact. 1994;91:165–180. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieder MJ, Krause R, Bird IA, Dekaban GA. Toxicity of sulfon-amide-reactive metabolites in HIV-infected, HTLV-infected, and noninfected cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:134–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mollace V, Nottet HS, Clayette P, et al. Oxidative stress and neuroAIDS: triggers, modulators and novel antioxidants. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:411–416. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01819-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palamara AT, Garaci E, Rotilio G, et al. Inhibition of murine AIDS by reduced glutathione. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:1373–1381. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kameoka M, Okada Y, Tobiume M, Kimura T, Ikuta K. Intracellular glutathione as a possible direct blocker of HIV type 1 reverse transcription. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:1635–1638. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eck HP, Stahl-Hennig C, Hunsmann G, Droge W. Metabolic disorder as early consequence of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques. Lancet. 1991;338:346–347. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garaci E, Palamara AT, Ciriolo MR, et al. Intracellular GSH content and HIV replication in human macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:54–59. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opalenik SR, Ding Q, Mallery SR, Thompson JA. Glutathione depletion associated with the HIV-1 TAT protein mediates the extra-cellular appearance of acidic fibroblast growth factor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;351:17–26. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi J, Liu RM, Kundu RK, et al. Molecular mechanism of decreased glutathione content in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3693–3698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raidel SM, Haase C, Jansen NR, et al. Targeted myocardial transgenic expression of HIV Tat causes cardiomyopathy and mitochondrial damage. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:H1672–H1678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00955.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith OW, Mulcahy RT. The enzymes of glutathione synthesis: gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Adv Enzymol Rel Areas Mol Biol. 1999;73:209–267. doi: 10.1002/9780470123195.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai J, Nelson KC, Wu M, Sternberg P, Jr, Jones DP. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu H, Miyauchi S, Bridges CC, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Identification of a novel Na+- and Cl--coupled transport system for endogenous opioid peptides in retinal pigment epithelium and induction of the transport system by HIV-1 Tat. Biochem J. 2003;375:17–22. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganapathy V, Mendicino J, Leibach FH. Transport of glycyl-L-proline into intestinal and renal brush border vesicles from rabbit. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:118–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganapathy V, Mendicino J, Leibach FH. Evidence for a dipeptide transport system in renal brush border membranes from rabbit. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;642:381–391. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajan DP, Kekuda R, Huang W, et al. Cloning and expression of a b0,+-like amino acid transporter functioning as a heterodimer with 4F2hc instead of rBAT: a new candidate gene for cystinuria. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29005–29010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Prasad PD, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. cDNA sequence, transport function, and genomic organization of human OCTN2, a new member of the organic cation transporter family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:589–595. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kouskoff V, Fehling H-J, Lemeur M, Benoist C, Mathis D. A vector driving the expression of foreign cDNAs in the MHC class II-positive cells of transgenic mice. J Immunol Methods. 1993;166:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90370-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jules RS, Smith SB, O’Brien PJ. The localization and timing of post-translational modifications of rat rhodopsin. Exp Eye Res. 1990;51:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90155-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meister A. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17205–17208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore P, El-Sherbeny A, Roon P, Schoenlein PV, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Apoptotic cell death in the mouse retinal ganglion cell layer is induced in vivo by the excitatory amino acid homocysteine. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:45–57. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman WR. Retinal disease associated with AIDS. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1993;21:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1993.tb00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harkins T. Noninfectious retinopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72:302–304. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuppermann BD. Noncytomegalovirus-related chorio-retinal manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol. 1995;10:125–141. doi: 10.3109/08820539509059989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond RR, Achim CL, Wiley CA. Neuropathology of the retina in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol. 1995;10:177–182. doi: 10.3109/08820539509059994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quiceno JI, Capparelli E, Sadun AA, et al. Visual dysfunction without retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:8–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donahue SP. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated vision loss: electroretinogram attenuation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:729–731. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sample PA, Plummer DJ, Mueller AJ, et al. Pattern of early visual field loss in HIV-infected patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:755–760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plummer DJ, Bartsch DU, Azen SP, Max S, Sadun AA, Freeman WR. Retinal nerve fiber layer evaluation in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartel P, Roux P, van Niekerk M. Vitamin A status in relation to electroretinographic and electrooculographic findings in HIV infection. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1234–1240. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jabs DA, Green WR, Fox R, Polk BF, Bartlett JG. Ocular manifestations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spalding JM. Central serous chorioretinopathy and HIV. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]