Summary

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium responsible for a number of health problems, including sexually transmitted infection in humans. We recently discovered that C. trachomatis infection in cell culture is highly susceptible to inhibitors of peptide deformylase, an enzyme that removes the N-formyl group from newly synthesized polypeptides. In this study, one of the deformylase inhibitors, GM6001, was tested for potential antichlamydial activity using a murine genital C. muridarum infection model. Topical application of GM6001 significantly reduced C. muridarum loading in BALB/c mice that were vaginally infected with the pathogen. In striking contrast, growth of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum is strongly resistant to the PDF inhibitor. GM6001 demonstrated no detectable toxicity against host cells. On the basis of these data and our previous observations, we conclude that further evaluation of PDF inhibitors for prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted chlamydial infection is warranted.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia muridarum, sexually transmitted infection, sexually transmitted disease, peptide deformylase, GM6001

Introduction

C. trachomatis is the most prevalent sexually transmitted pathogen worldwide and is also the top cause of preventable blindness in developing countries (Schachter, 1999). In women, sexually transmitted chlamydial infection causes cervicitis, endometritis and salpingitis. These conditions contribute to ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage and premature birth (Schachter, 1999). In men, the infection leads to urethritis that is frequently accompanied by proctitis in men who have sex with men (Schachter, 1999; Williams and Churchill, 2006).

C. trachomatis is sensitive to a number of antibiotics. However, the majority of infected individuals—even in developed countries—do not seek treatment because they have no or very mild symptoms (Schachter, 1999). Without proper antibiotic treatment, about one third of infected individuals develop long-term, devastating complications, such as infertility and chronic pelvic inflammatory pain syndrome (Schachter, 1999). Infected individuals are also at increased risk of HIV acquisition, owing to ulcerative damages that occur in the epithelial tissues (Stamm et al., 1988). The medical and financial burdens of these conditions call for development of new strategies to effectively prevent C. trachomatis infection.

We have recently discovered that the infection of C. trachomatis in vitro is susceptible to hydroxamic acid-based compounds, including GM6001 and TAPI-0 (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). Specifically, genetic and biochemical analyses demonstrated that these compounds inhibit C. trachomatis by targeting peptide deformylase (PDF) (Balakrishnan et al., 2006), which catalyzes the removal of N-formyl group from the initiator methionine of newly synthesized proteins, the first reaction of the protein maturation pathway in bacteria (Yuan and White, 2006). Interestingly, the growth of commensal bacteria, Lactobacillus and Escherichia coli, is not affected by the compounds (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). If PDF inhibitors are found to be effective against chlamydial infection in vivo, we reason that they may offer advantages over traditional antibiotics in which PDF inhibitors may not disrupt normal microflora. Here we demonstrate inhibition of chlamydial infection by GM6001 in a chlamydial murine genital infection model. We further demonstrate that L. plantarum, a probiotic bacterium, is highly resistant to the PDF inhibitor. These findings suggest that PDF inhibitors deserve further evaluation as antichlamydial candidates for the prevention of sexually transmitted chlamydial infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and reagents

Strain 434/bu of C. trachomatis serovar L2 (L2), strain Nigg II of C. muridarum, traditionally referred to as mouse pneumonitis pathogen (MoPn) and Lactobacullus plantarum (strain 8014) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Chlamydial stocks were amplified with HeLa cells (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). The infectivities of the stocks were determined by titrating inclusion formation on HeLa cell monolayers as we reported previously (Fan, 1994; Fan et al., 1992). L. plantarum was cultured with Lactobacillus MRS Broth. GM6001 (N-[(2R)-2-(hydroxamidocarbonyl methyl)-4-methyl pentanoyl]-L-tryptophan methylamide) was purchased from Calbiochem. [Methyl-3H]thymidine (specific activity: 20 Ci/mmole) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). A monoclonal antibody designated M5H9, which recognizes chlamydial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), was a kind gift from Dr. Guangming Zhong (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Texas) (Greene et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2004).

Cell culture and infection

HeLa cells were maintained as adherent culture using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 50 µg/ml gentamycin at 37 ºC in a 5% CO2 incubator. Infection and drug treatment were carried out as previously reported (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). Briefly, HeLa cells were seeded onto 24 well plates. After overnight culture, they were exposed to an L2 or MoPn stock for 2 h. Cells were then washed and fed with medium containing GM6001 or the solvent DMSO (final concentration: 1%). To determine the effect of GM6001 on inclusion formation, cells were fixed with 100% methanol at 30 h after infection, and then soaked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were viewed under an Olympus IX-51 invert microscope and images were obtained with an Olympus monochrome camera (model S97827). Cells were then sequentially reacted with the anti-LPS monoclonal M5H9 antibody and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. After final washes, cells were overlaid with a solution containing 50% glycerin and 2.3% 1,4 diazabizyclo[2.2.2]octane, an antifade reagent. Immunostained inclusions were imaged with the Olympus IX-51 invert microscope using an FITC filter (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). To determine the bactericidal activity of GM6001, the infected cells were harvested in fresh medium. EBs were released by sonication, serially diluted and inoculated onto HeLa monolayers. Thirty h later, the number of inclusions were stained as described above and scored (Balakrishnan et al., 2006).

Determination of DNA synthesis

DNA synthesis was determined by measuring the incorporation of [methyl-3H]thymidine, using a previously reported protocol (Fan, 1994; Fan et al., 1992) with modifications. HeLa cells were seeded onto 24 well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells. After overnight incubation, the cells were switched into 0.5 ml medium containing GM6001. After an additional 40 h of incubation, [methyl-3H]thymidine (2 µl/well) was added into the medium. The labeling medium was removed 2 h later. Cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 100% methanol. Free unincorporated nucleoside and nucleotides were washed off with PBS. Cells were solubilized in 200 µl of 1N NaOH and were then neutralized with equal volume of 1N HCl. The amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated into DNA was determined by scintillation counting of the neutralized cell lysate (Fan, 1994; Fan et al., 1992).

Microscopy of cellular and nuclear morphology

Cell seeding and GM6001 treatment were performed in the same manner as for determination of DNA synthesis. To record gross cellular morphology, life (unfixed) cells were photographed as described above. Cells were then fixed with methanol, and overlaid with the antifade solution (described above) supplemented with 1 µg/ml 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Nuclear morphology was viewed with the Olympus IX-51 microscope using a DAPI filter; images were obtained as described above.

Infection and treatment of mice

The care of experimental animals was in accordance with guidelines set by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee. Medroxyprogesterone was used to make mice susceptible to infection (Barron et al., 1981). Eight-week old Balb/c female mice were injected subcutaneously with the hormone (2.5 mg/mouse) two weeks before infection. The injection was repeated seven days before infection. The progesterone-treated animals were given intravaginally either 10 µl of 1 mM GM6001 prepared in 50 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.0) (Schultz et al., 1992) or the vehicle Hepes buffer (10 mice in each group). One hour later, the animals were infected intravaginally with MoPn (2 × 107 IFUs per mouse). After infection, intravaginal administration of GM6001 or vehicle was repeated three times per day. Four, 10, 15 and 18 days after infection, vaginal swabs were taken. Infectious elementary bodies on the swabs were eluted into 1.0 ml sucrose-phosphate-glutamate buffer, serially diluted and inoculated onto HeLa cells grown on cover slips. After 30 h of culture, coverslips were fixed with methanol. Immunostaining and fluorescence microscopy were performed as described above.

Statistical analysis

A repeated measures ANOVA (Littell RC, 1996) was used to evaluate the effectiveness of GM6001. In order to satisfy distributional assumptions (normal distribution and equality of variances among drug-time groups of measurements), a logarithmic transform was taken of the inclusion counts. Counts of 0 were set to 1 before the logarithmic transform. After testing for an overall difference between the treated and control mice, pairwise comparisons of least square means were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the test drug at each individual time point. SAS (SAS Institute Inc., 1999) was used to process the analyses.

GM6001 on L. plantarum growth

MRS agar was autoclaved and cooled to 45 ºC. After the addition of GM6001 the agar was poured onto 6-well plates. An overnight L. plantarum suspension culture was diluted 1:50 and inoculated to the solidified agar (20 µl/well). The growth of L. plantarum was examined after 24 h culture at 37 ºC.

Results

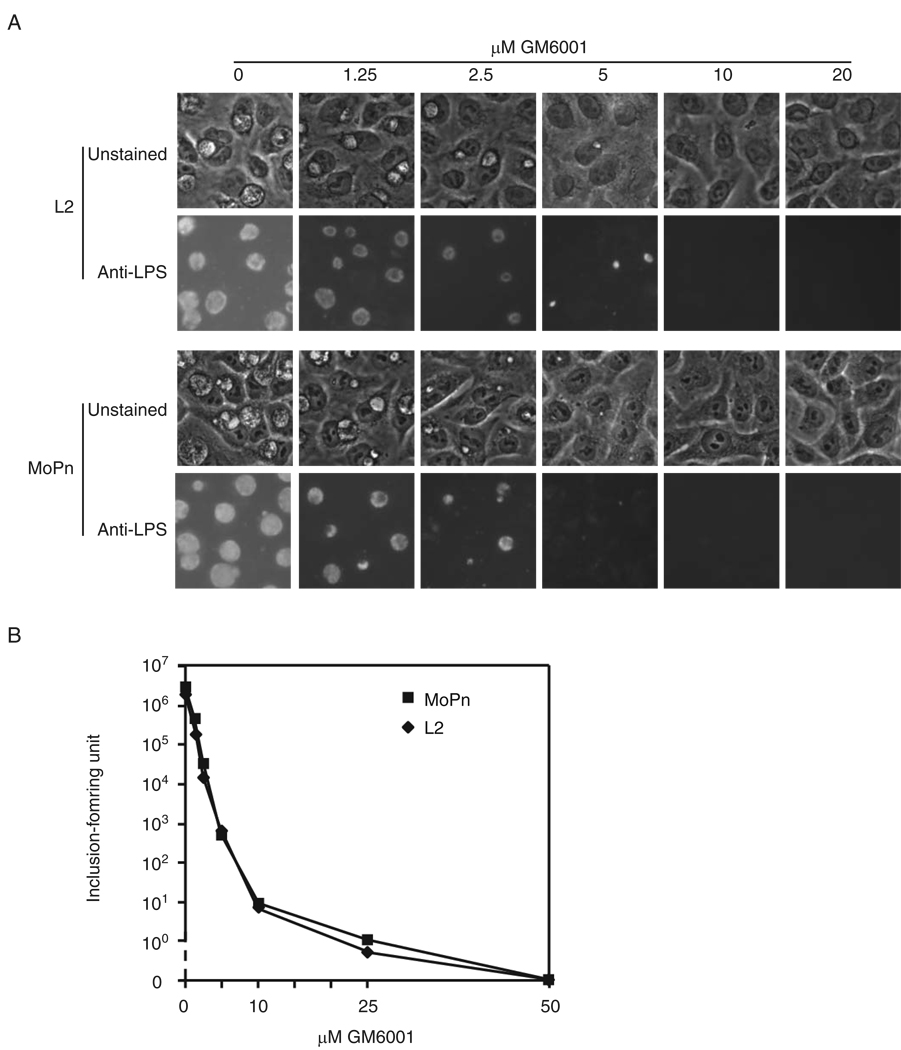

Inhibition of MoPn infection by GM6001 in vitro

We previously characterized the inhibition of C. trachomatis L2, a human pathogen, in cell culture by GM6001 (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). In this study, we wanted to address whether GM6001 would also inhibit chlamydial infection in vivo. Since mice in general seem to be resistant to C. trachomatis isolates, we chose a previously established mouse model in which the mouse pathogen MoPn is inoculated vaginally (de la Maza et al., 1994). Although MoPn has been reclassified from C. trachomatis to C. muridarum under the most recent taxonomy, it is the only organism that models human chlamydial infections in mice at the present time. To ensure that the mouse model can be utilized to assess the efficacy of PDF inhibitors, we first compared the effects of GM6001 on the growth of L2 and MoPn in tissue culture. Dose-dependent inhibition of L2 and MoPn inclusion formation was readily observed in unstained cells, which was further confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1A). In both strains the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC, defined as apparent minimal GM6001 concentration needed to completely inhibit inclusion formation) was 10 µM (Fig. 1A) whereas the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC, minimal concentration required to completely block the production of progeny EBs) was 50 µM (Fig. 2B). Thus, the PDF inhibitor is equally potent toward L2 and MoPn.

Fig. 1.

Equal potency of GM6001 against L2 and MoPn growth in cell culture. HeLa cells were infected with L2 or MoPn and cultured with indicated concentrations of GM6001. A. The infected cells were photographed unstained or after being stained with an anti-chlamydial LPS primary antibody and an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. B. The titers of progeny EBs produced in the presence of indicated GM6001 concentrations were determined by immunostaining and scoring inclusions that grew in secondary cultures.

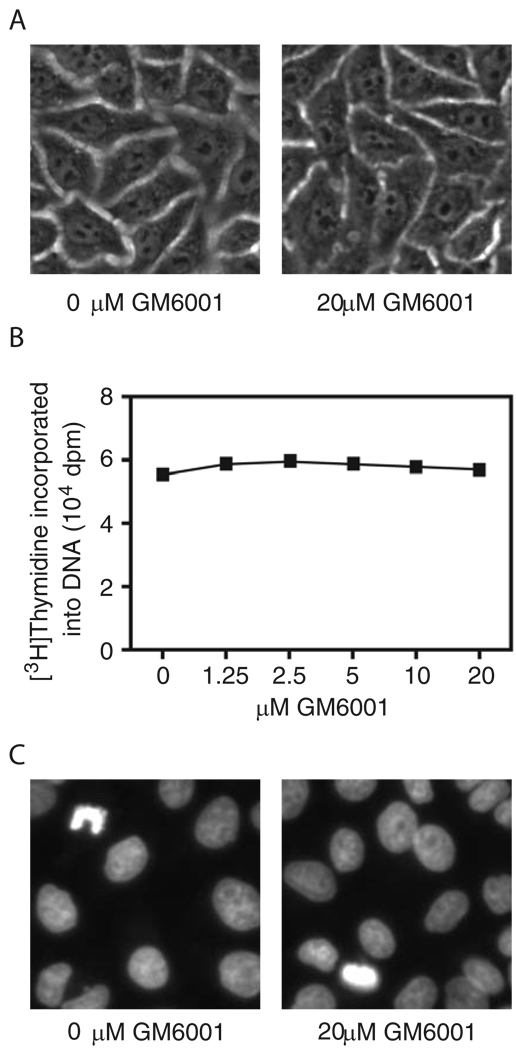

Fig. 2.

Lack of effects of GM6001 on gross morphology (A), DNA synthesis (B) and nuclear morphology (C) of uninfected HeLa cells. Note that in (C) the condensed nuclei with highly increased fluorescence signals as compared to the majority of nuclei shown are characteristic of apoptosis.

Tolerance of GM6001 by host cells

We assessed possible toxicity of GM6001 in HeLa cells by gross cellular morphology and DNA synthesis and staining in the presence and absence of GM6001. Life cell imaging (Fig. 2A) revealed no changes in gross morphology of cells cultured in the presence of 20 µM GM6001 as compared with those grown in the absence of the compound. DNA synthesis activities as determined by incorporation of [methyl-3H]thymidine were the same in cells cultured in the presence of GM6001 ranged from 1.25 to 20 µM as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 2B). Finally, GM6001-treated cells exhibited the same nuclear morphology as untreated cells, as demonstrated by staining with DAPI (Fig. 2C). Consistent with previous observations (Shi et al., 1994), chromatin condensation, a hallmark of apoptosis, was found in a small number of untreated HeLa cells (3.6 ± 2.7 per field of a 40 X objective, average ± standard deviation of counts from 10 randomly selected fields). Essentially the same proportion of control vehicle-treated cells (3.8 ± 3 per field) was found to contain condensed chromatin. In summary, we observed no detectable toxicity of GM6001 in HeLa cells.

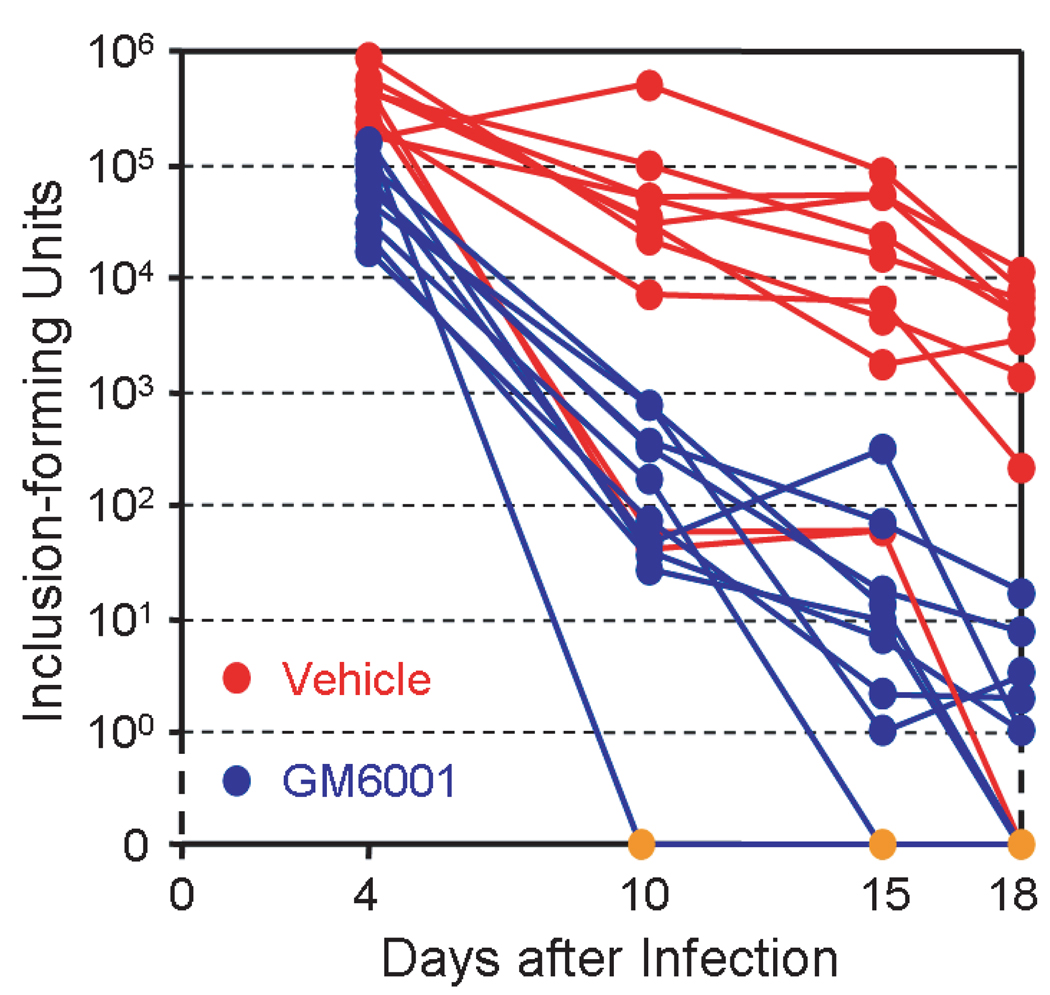

Inhibition of Chlamydia in vivo by GM6001

We next tested the effects of GM6001 on C. trachomatis infection in vivo using a MoPn vaginal infection model previously established in BALB/c mice. Intravaginal application of GM6001 was described in the “Materials and Methods” section. The numbers of infectious EBs recovered from vaginal swabs taken from each animal at various days after the infection are shown in Fig. 3. It is apparent that the majority (8/10) of control vehicle-treated mice had higher bacterial loadings as compared with GM-6001-treated animals. In addition, while some mice treated with GM6001 reached Chlamydia-free status 10–15 days after infection, the earliest time that the control mice reached this state (through their immune response) was 18 days after infection (Fig. 3). Means, standard deviations and geometric means of the EB counts are presented in Table 1. The differences in EB loadings between GM6001-treated and vehicle-treated mice were significant for all days, with p-values of <0.0001 (t=6.71, d.f.=18), 0.0005 (t=4.25, d.f.=18), <0.0001 (t=6.83, d.f.=18) and <0.0001 (t=4.95, d.f.=18) for days 4, 10, 15 and 18, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of MoPn infection in mice by GM6001. Vaginal Infection with MoPn and topical application of GM6001 were carried out as described in the “Materials and Methods” Section. EB titers of vaginal swabs of individual animals at each time point are shown. Note the y-axis on logarithmic scale was manually extended to zero to indicate nondetection of EBs (gold dots) in some animals.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for EB counts of vaginal swabs

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Geometric Mean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM6001 | Vehicle | GM6001 | Vehicle | |

| Day 4 | 171,000.0 (110,114.8) |

1,064,500.0 (533,694.9) |

137,657.3 | 944,196.3 |

| Day 10 | 632.1 (726.5) |

218,2332.5 (385,503.9) |

205.3 | 31,767.9 |

| Day 15 | 105.5 (241.9) |

61,428.8 (71,432.7) |

15.5 | 15,188.7 |

| Day 18 | 8.2 (12.6) |

10,475.2 (10,064.3) |

3.4 | 1,364.1 |

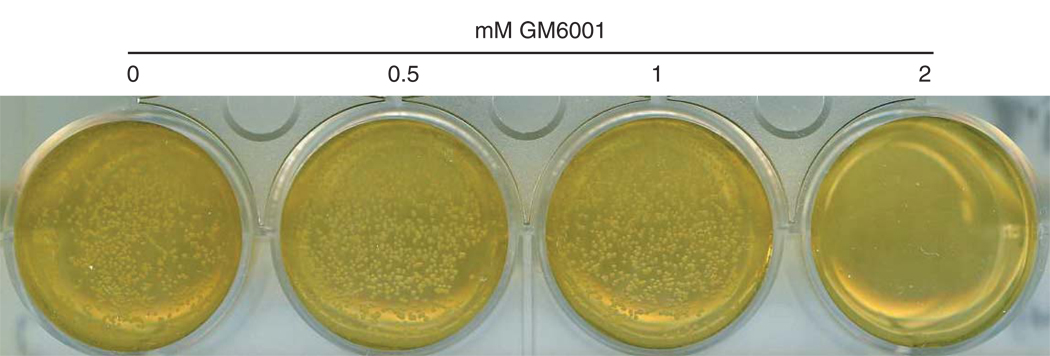

Resistance to GM6001 in L. plantarum

We have previously reported a lack of effects of GM6001 and TAPI-0 on L. delbrueckii and E. coli, found in the vagina and gastrointestine, respectively (Balakrishnan et al., 2006). We now have determined that the H2O2- and lactic acid-producing L. plantarum, which is a common component of normal vaginal microflora and is under consideration for prevention of bacterial vaginosis (Bonetti et al., 2003; Kilic et al., 2005; Ronnqvist et al., 2006), is also highly resistant to GM6001. Accordingly, the growth of the probiotic organism was not affected by GM6001 at concentrations up to 1 mM (Fig. 4). Thus, L. plantarum was at least 100 times less susceptible to the PDF inhibitor as compared with C. trachomatis.

Fig. 4.

Growth tolerance to GM6001 in L. plantarum.

Discussion

C. trachomatis is the most prevalent sexually transmitted pathogen (Schachter, 1999). Although infected individuals are often asymptomatic, the infection can lead to long-term, devastating complications in about one third of untreated cases, particularly among women. In addition, chlamydial infection also predisposes individuals to HIV infection (Stamm et al., 1988). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop effective preventive strategies that does not rely on condom use (Frick et al., 2004; Gulati et al., 2001; Holt et al., 2006), given that many studies have found that the majority of sexually active individuals do not consistently use condoms during intercourse [e.g. (Eisenberg, 2002; Yang et al., 2005)]. One of the proposed strategies for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections has been topical antimicrobials that women can apply to themselves before having intercourse (Achilles et al., 2002; Ballweber et al., 2002; Bourne et al., 2003; Holt et al., 2006; Lampe et al., 1998). Classical antibiotics are undesirable for long-term, prophylactic use because they frequently disrupt normal microflora and consequently increase the risk for bacterial vaginosis (Antonio et al., 2005; Knight et al., 1987; Sha et al., 2005; Vallor et al., 2001). Among non-antibiotic reagents tested against C. trachomatis, only one offered partial protection in vivo; others were either ineffective or may even worsen the infection in vivo (due to their disruptive effects on the vaginal epithelia) although, in vitro, they demonstrated adverse effects on the pathogen (Achilles et al., 2002; Ballweber et al., 2002; Bourne et al., 2003; Lampe et al., 1998). As shown in the present study, topical application of 1 mM GM6001 solution significantly decreased vaginal chlamydial loading. Nevertheless, the inhibition was also only partial. The most likely reason for the incomplete in vivo inhibition was the failure of the compound to remain sufficiently high in concentration in the vaginal epithelial tissue. Without testing alternative formulations for the solubility and stability of GM6001, we chose an neutral, aqueous solution (buffered by Hepes) that has been used previously for demonstrating a therapeutic effect of GM6001 in an eye injury animal model (Schultz et al., 1992). (A neutral Hepes buffer appeared to be safe for vaginal application in a previous mouse gonorrhoeae model (Jerse, 1999) although an acidic carrier with a pH value close to that in the vagina would probably be more desirable for vaginal use). Since the concentration of GM6001 solution used in this study is only 1 mM (which is near the compound’s saturation points in the neutral, aqueous solution), it would not be surprising if the concentration of GM6001 drops below the MBC (50 µM) after the application of the solution given that any aqueous solution is likely to be retained poorly in the vagina. In addition, the vaginal secretion, which likely increased in response to infection, may also dilute the compounds. Finally, it is also possible that the concentration of the PDF inhibitor in the vagina can be lowered as a result of absorption and consequent systemic distribution. Thus, alternative formulation is needed to improve the efficacy of GM6001 as a topical reagent for the prevention of chlamydial infection.

GM6001 and TAPI-0 were originally developed as metalloprotease inhibitors (Feehan et al., 1996; Levy et al., 1998). Their targets in mammals include matrix metalloproteases and membrane anchored ectoproteases, including tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme (TACE) (Balakrishnan et al., 2006; Feehan et al., 1996; Levy et al., 1998). It is not known whether this lack of specificity against chlamydial PDF is a desirable property for an antichlamydial. On the one hand, although GM6001 demonstrated undetectable effects on the gross morphology, DNA synthesis and nuclear morphology (Fig. 2), potential toxicity should not be ruled out. On the other hand, complications from chlamydial infection, including chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility, are largely due to inflammatory damages. Matrix metalloproteases of the host have been indicated as mediators of such processes (Imtiaz et al., 2006; Ramsey et al., 2005). Furthermore, TACE is responsible for the release of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Li and Fan, 2004). Therefore, one may also argue that in addition to directly abrogating chlamydial replication, compounds like GM6001 and TAPI-0 may inhibit inflammation and consequently decrease tissue damage and reduce the risk of serious complications. Indeed, a very recent study demonstrated inhibition of ascending infection of C. trachomatis in mice (despite its lack of a direct effect on chlamydial replication) by non-hydroxamate-based metalloproteases inhibitors (Imtiaz et al., 2006). Therefore, it would be very worthwhile to further explore dual-specific inhibitors for C. trachomatis infection. It should also be pointed out that PDF inhibitors with much decreased activity against metalloproteases have been developed (Chen and Yuan, 2005). If PDF-specific inhibitors are found to be effective in vivo against C. trachomatis as well, comparative analyses can be conducted to determine whether cross-inhibition of host metalloprotease activity is a more or less desirable strategy than inhibition of only PDF for combating chlamydial infection in vivo.

All prokaryotes are believed to require PDF activity. Although the amino acid sequences of PDF are only moderately (30–40%) conserved, the PDF proteins from different species share a highly conserved tertiary structure (Kreusch et al., 2003). Thus, all bacteria should be susceptible to PDF inhibition. Indeed, enzyme activities of all bacterial PDFs are effectively inhibited by the hydroxamate-based inhibitors studied to date (Kreusch et al., 2003). However, susceptibility to the compounds varies greatly among species (Jones et al., 2004). Resistance to other hydroxamate-based PDF inhibitors in E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae is mediated by efflux pumps (Chen et al., 2000; Dean et al., 2005). The same mechanism is likely to be responsible for GM6001 resistance in E. coli and Lactobacilli. Although it has been a direction of past research to develop PDF inhibitors into broad spectrum antibacterials (Matijevic-Sosa and Cvetnic, 2005), it is desirable to maintain the trait of ineffectiveness against lactobacilli, E. coli and other commensal organisms in the vagina and rectum in developing PDF inhibitors for vaginal and rectal use for combating sexually transmitted infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Guangming Zhong for supplying the anti-LPS antibody. This work was supported in part by grants from the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, the National Institutes of Health (1R21AI064441) and the National Center of the American Heart Association (Grant 0330335N) (to H. F.).

Abbreviations

- EB

chlamydial elementary body

- MOMP

chlamydial major outer membrane protein

- LPS

lipopolysacharide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SPG

sucrose phosphate glutamate buffer

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achilles SL, Shete PB, Whaley KJ, Moench TR, Cone RA. Microbicide efficacy and toxicity tests in a mouse model for vaginal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:655–664. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonio MA, Rabe LK, Hillier SL. Colonization of the rectum by Lactobacillus species and decreased risk of bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:394–398. doi: 10.1086/430926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan A, Patel B, Sieber SA, Chen D, Pachikara N, Zhong G, Cravatt BF, Fan H. Metalloprotease Inhibitors GM6001 and TAPI-0 Inhibit the Obligate Intracellular Human Pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis by Targeting Peptide Deformylase of the Bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. %R 10.1074/jbc.M513648200. 2006;281:16691–16699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballweber LM, Jaynes JE, Stamm WE, Lampe MF. In vitro microbicidal activities of cecropin peptides D2A21 and D4E1 and gel formulations containing 0.1 to 2% D2A21 against Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:34–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.34-41.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron AL, White HJ, Rank RG, Soloff BL, Moses EB. A new animal model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections: infection of mice with the agent of mouse pneumonitis. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:63–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti A, Morelli L, Campominosi E, Ganora E, Sforza F. Adherence of Lactobacillus plantarum P 17630 in soft-gel capsule formulation versus Doderlein's bacillus in tablet formulation to vaginal epithelial cells. Minerva Ginecol. 2003;55:279–284. 284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne N, Zaneveld LJ, Ward JA, Ireland JP, Stanberry LR. Poly(sodium 4-styrene sulfonate): evaluation of a topical microbicide gel against herpes simplex virus type 2 and Chlamydia trachomatis infections in mice. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:816–822. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Yuan Z. Therapeutic potential of peptide deformylase inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:1107–1116. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DZ, Patel DV, Hackbarth CJ, Wang W, Dreyer G, Young DC, Margolis PS, Wu C, Ni ZJ, Trias J, White RJ, Yuan Z. Actinonin, a naturally occurring antibacterial agent, is a potent deformylase inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1256–1262. doi: 10.1021/bi992245y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Maza L, Pal S, Khamesipour A, Peterson E. Intravaginal inoculation of mice with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar results in infertility. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:2094–2097. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2094-2097.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean CR, Narayan S, Daigle DM, Dzink-Fox JL, Puyang X, Bracken KR, Dean KE, Weidmann B, Yuan Z, Jain R, Ryder NS. Role of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in determining susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae to the novel peptide deformylase inhibitor LBM415. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3129–3135. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3129-3135.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME. The association of campus resources for gay, lesbian, and bisexual students with college students' condom use. J Am Coll Health. 2002;51:109–116. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H. Department of Medical Microbiology. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 1994. Thymidylate Synthesis and Folate Metabolism by the Obligate Intracellular Parasite Chlamydiae - Metabolic Studies and Molecular Cloning; pp. 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Brunham RC, McClarty G. Acquisition and synthesis of folates by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Chlamydia. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1803–1811. doi: 10.1172/JCI116055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feehan C, Darlak K, Kahn J, Walcheck B, Spatola AF, Kishimoto TK. Shedding of the lymphocyte L-selectin adhesion molecule is inhibited by a hydroxamic acid-based protease inhibitor. Identification with an L- selectin-alkaline phosphatase reporter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7019–7024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KD, Colchero MA, Dean D. Modeling the economic net benefit of a potential vaccination program against ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Vaccine. 2004;22:689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene W, Xiao Y, Huang Y, McClarty G, Zhong G. Chlamydia-infected cells continue to undergo mitosis and resist induction of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:451–460. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.451-460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati S, Ngampasutadol J, Yamasaki R, McQuillen DP, Rice PA. Strategies for mimicking Neisserial saccharide epitopes as vaccines. Int Rev Immunol. 2001;20:229–250. doi: 10.3109/08830180109043036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt BY, Morwitz VG, Ngo L, Harrison PF, Whaley KJ, Pettifor A, Nguyen AH. Microbicide preference among young women in California. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:281–294. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz MT, Schripsema JH, Sigar IM, Kasimos JN, Ramsey KH. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases protects mice from ascending infection and chronic disease manifestations resulting from urogenital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5513–5521. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00730-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerse AE. Experimental gonococcal genital tract infection and opacity protein expression in estradiol-treated mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5699–5708. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5699-5708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN, Moet GJ, Sader HS, Fritsche TR. Potential utility of a peptide deformylase inhibitor (NVP PDF-713) against oxazolidinone-resistant or streptogramin-resistant Gram-positive organism isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:804–807. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E, Aslim B, Taner Z. Susceptibility to some antifungal drugs of vaginal lactobacilli isolated from healthy women. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2005;21:67–74. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2005.21.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight ST, Lee SH, Davis CH, Moorman DR, Hodinka RL, Wyrick PB. In vitro activity of nonoxynol-9 on McCoy cells infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1987;14:165–173. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198707000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreusch A, Spraggon G, Lee CC, Klock H, McMullan D, Ng K, Shin T, Vincent J, Warner I, Ericson C, Lesley SA. Structure analysis of peptide deformylases from Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Thermotoga maritima and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: snapshots of the oxygen sensitivity of peptide deformylase. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:309–321. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00596-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe MF, Ballweber LM, Stamm WE. Susceptibility of Chlamydia trachomatis to chlorhexidine gluconate gel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1726–1730. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Lapierre F, Liang W, Ye W, Lange CW, Li X, Grobelny D, Casabonne M, Tyrrell D, Holme K, Nadzan A, Galardy RE. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: a structure-activity study. J Med Chem. 1998;41:199–223. doi: 10.1021/jm970494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Fan H. Loss of Ectodomain Shedding Due to Mutations in the Metalloprotease and Cysteine-rich/Disintegrin Domains of the Tumor Necrosis Factor-{alpha} Converting Enzyme (TACE) J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:27365–27375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Stroup MG, Wolfinger RD WW. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1996. SAS System for Mixed Models. [Google Scholar]

- Matijevic-Sosa J, Cvetnic Z. Antimicrobial activity of N-phthaloylamino acid hydroxamates. Acta Pharm. 2005;55:387–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey KH, Sigar IM, Schripsema JH, Shaba N, Cohoon KP. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases subsequent to urogenital Chlamydia muridarum infection of mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6962–6973. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6962-6973.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnqvist PD, Forsgren-Brusk UB, Grahn-Hakansson EE. Lactobacilli in the female genital tract in relation to other genital microbes and vaginal pH. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:726–735. doi: 10.1080/00016340600578357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS ® User’s Guide, Version 8. Cary, N.C.: SAS institute, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J. Infection and disease epidemiology. In: Stephens RS, editor. Chlamydia Intracellular Biology, Pathogenesis. ASM Press: Washington DC; 1999. pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz GS, Strelow S, Stern GA, Chegini N, Grant MB, Galardy RE, Grobelny D, Rowsey JJ, Stonecipher K, Parmley V, et al. Treatment of alkali-injured rabbit corneas with a synthetic inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:3325–3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha BE, Zariffard MR, Wang QJ, Chen HY, Bremer J, Cohen MH, Spear GT. Female genital-tract HIV load correlates inversely with Lactobacillus species but positively with bacterial vaginosis and Mycoplasma hominis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:25–32. doi: 10.1086/426394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Nishioka WK, Th'ng J, Bradbury EM, Litchfield DW, Greenberg AH. Premature p34cdc2 activation required for apoptosis. Science. 1994;263:1143–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.8108732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm WE, Handsfield HH, Rompalo AM, Ashley RL, Roberts PL, Corey L. The association between genital ulcer disease and acquisition of HIV infection in homosexual men. Jama. 1988;260:1429–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallor AC, Antonio MA, Hawes SE, Hillier SL. Factors associated with acquisition of, or persistent colonization by, vaginal lactobacilli: role of hydrogen peroxide production. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1431–1436. doi: 10.1086/324445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Churchill D. Ulcerative proctitis in men who have sex with men: an emerging outbreak. BMJ %R 10.1136/bmj.332.7533.99. 2006;332:99–100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7533.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Zhong Y, Greene W, Dong F, Zhong G. Chlamydia trachomatis Infection Inhibits Both Bax and Bak Activation Induced by Staurosporine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5470–5474. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5470-5474.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, Mao R, Liu H, Chen X, Severson R. Workplace and HIV-related sexual behaviours and perceptions among female migrant workers. AIDS Care. 2005;17:819–833. doi: 10.1080/09540120500099902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z, White RJ. The evolution of peptide deformylase as a target: Contribution of biochemistry, genetics and genomics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]