Abstract

Rationale

We investigated whether proposed “quality markers” within the medical record are associated with family assessment of the quality of dying and death in the ICU.

Objective

To identify chart-based markers that could be used as measures for improving the quality of end-of-life care.

Design

A multi-center study conducting standardized chart abstraction and surveying families of patients who died in the ICU or within 24 hours of being transferred from an ICU.

Setting

ICUs at ten hospitals in the Northwest US.

Patients

356 patients who died in the ICU or within 24 hours of transfer from an ICU.

Measurements

1) the 22-item family-assessed Quality of Dying and Death (QODD-22); 2) a single item rating of the overall quality of dying and death (QODD-1).

Analysis

The associations of chart-based quality markers with QODD scores were tested using Mann-Whitney tests, Kruskal Wallis tests, or Spearman correlation coefficients as appropriate.

Results

Higher QODD-22 scores were associated with documentation of a living will (p = 0.03), absence of CPR performed in the last hour of life (p = 0.01), withdrawal of tube feeding (p = 0.04), family presence at time of death (p=0.02), and discussion of the patient’s wish to withdraw life support during a family conference (p<0.001). Additional correlates with a higher QODD-1 score included use of standardized comfort care orders and occurrence of a family conference (p≤0.05).

Conclusions

We identified chart-based variables associated with higher QODD scores. These could serve as targets for measuring and improving the quality of end-of-life care in the ICU.

MeSH Headings: Palliative Care, Critical Care, Family Satisfaction, Intensive Care/*statistics & numerical data, *Attitude to Death, Quality indicators, Health Care

Introduction

Approximately one in five deaths in the U.S. occur in the intensive care unit (ICU), and an increasing proportion of these patients have life support withdrawn prior to death.(1,2,3,4,5) As a result, there is increasing emphasis on improving end-of-life care in the ICU. Nonetheless, there is ample evidence that there remains significant room for improvement in the care of these patients.(6,7,8,9) Due to inherent challenges in assessing patients’ dying experience, it is difficult to measure the quality of care of these patients. Surrogate markers such as ICU length of stay are markers of intensity of care, but may not directly reflect the quality of end-of-life care.(10) Therefore, after-death surveys of caregivers and family members that directly assess the quality of end-of-life care or that assess related constructs, such as the Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire (QODD) or the quality of life at the end-of-life, have emerged as potential indirect measures of the quality of end-of-life care.(11,12) Despite the use of such tools to generate conceptual models and targets for improving end-of-life care, the lack of measurable, reproducible quality markers remains a major barrier to quality improvement.(13)

The search for measures of quality of end-of-life care in the ICU has been complicated by poor documentation of end-of-life care in the medical record.(14, 15, 16) Thorough documentation has been shown to be an important component of quality improvement. (17, 18) Thus, an important step in improving the quality of end-of-life care in the ICU is to determine if the medical record can capture elements that are associated with the quality of the dying and death experience.

In this study we used the medical record as a source of potential predictors of the QODD score. We sought to determine if potentially modifiable quality markers, selected based on prior research and abstracted from medical records, were associated with the QODD. Such predictors, if shown to be reliable and valid, could be used to design and assess implementation of interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care in the ICU.

Methods

Hospital sites and patients

Data were collected as part of an ongoing cluster randomized trial to evaluate the effects of an interdisciplinary intervention to improve the quality of care for patients who die in the ICU at 15 hospitals in western Washington.(19) Data in this report are based on baseline assessments (prior to implementation of the intervention) at ten of the hospitals for which chart abstraction and questionnaire data were available at the time of this analysis. All patients who died in the participating ICUs or within 24 hours of transfer from the ICU were identified using admission/discharge/transfer logs. All patients who died in the ICU during the study period (data collected from 8/9/03 to 11/27/2005) were eligible for the study. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved the study, as did all participating hospitals. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract.(20)

The ten hospitals in these analyses included a University-affiliated county hospital (65 ICU beds), two community-based teaching hospitals (44 and 45 ICU beds) and seven community-based, non-teaching hospitals (ranging in size from 15-32 ICU beds).

QODD Questionnaire

The outcome variable used in this analysis was the 22-item Quality of Dying and Death (QODD-22) family survey which was derived from the initial 31-item QODD. The 31-item QODD was developed through qualitative studies of patients, family members and clinicians and was validated in two samples: 1) a community-based study of 205 patients who died in Missoula County; and 2) a hospice-based study of 95 patients.(21,22,23) The 31-item QODD was found to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.86) and construct validity, correlating with measures of symptom burden, patient-clinician communication about treatment preferences and other measures of quality of care.(22,23). An ICU version of the QODD had statistically significant, moderate inter-rater reliability when used in a population of ICU patients in which the survey was completed by two to four family member and demonstrated good construct validity in the ICU setting.(24,25) The responsiveness and factor structure of the QODD have not been determined.

In this study, we used the version of the QODD survey (QODD-22) designed for completion by family members of patients who die in the ICU setting to measure the family perspective of the dying experience. Items were omitted from the longer 31-item QODD that were inappropriate for the ICU setting. Items are rated on an 11 point scale, ranging from zero (a “terrible experience) to ten (an “almost perfect” experience). The QODD total score is obtained by summing the scores for all completed items and dividing by the number of completed items. This score is then multiplied by ten in order to obtain a final score on a scale of zero to 100. We calculated total scores for families who provided answers to at least five of 22 items. Analyses of QODD scores based on 1, 5 or 14 or more valid responses per family member indicated that QODD scores were significantly higher using 1 valid response only; scores using 5 or 14 or more items were unbiased (data not shown). The 22-item QODD questionnaire used in this study as well as the original 31-item QODD are available from the developers (http://depts.washington.edu/eolcare).

Single item for the overall rating of the quality of dying

In order to provide an additional assessment of the patient’s experience from the family’s perspective, we used a single item summary question “Overall, how would you rate the quality of your loved one’s dying?” This item, the QODD-1, is not contained within the QODD-22. and was of interest because of its potential utility as a succinct measure of the effect of interventions on the quality of dying and death. It was scored using the same 0 to 10 scale as the other QODD items.

Survey Methods

Family members were identified using two approaches. At one site, patients’ next of kin were identified from electronic medical records. At the other nine sites, surveys were sent to patients’ homes and addressed to the “Family of [patient’s name]”. Surveys were mailed to family members one to two months after the patient’s death along with a consent form, a ten dollar incentive, and a cover letter. A reminder/thank you postcard was sent one to two weeks later. If the questionnaire packet was not received within the following three weeks, a final mailing with the cover letter, consent form, and survey was sent.

Chart abstraction

Study patients’ medical records were reviewed by trained chart abstractors using a standardized chart abstraction protocol. Chart abstractor training included at least 80 hours of formal training. Training included instruction on the protocol, guided practice charts, and independent chart review followed by reconciliation with the research abstractor trainer. Abstractors were required to reach 90 percent agreement with the trainer before being able to code independently. After initial training, five percent of the charts were co-reviewed to ensure greater than 95 percent agreement on the 440 abstracted data elements.

Selection of variables

Demographic data were collected for all patients. The first ICD9 code listed in the patient’s chart was used as the primary diagnosis. The family’s demographic information was collected from questionnaires. Potentially modifiable variables from chart abstraction were identified a priori based on our hypotheses that these variables would be associated with the quality of end-of-life care. Hypotheses were based on previously published domains of the quality of end-of-life care in the ICU.(13, 26, 27) (Table 1)

Table 1.

Variables abstracted from the medical record according to end-of-life care domains

| Patient and family centered decision making |

| Documentation of the presence of a living will |

| Documentation of the presence of DPOAHC |

| Family’s wish to withdraw life support documented |

| Patient’s wish to withdraw life support documented |

| Patient’s opinions documented |

| Family present at time of death |

| Communication within the team and with patients and families |

| Documented family conference occurred in the first or last 72 hours |

| Prognosis discussion documented |

| Physician’s recommendation to withdraw life support documented |

| Decision to withdraw life support documented |

| Documentation of family discord |

| Documentation of discord between family and physician |

| Emotional and practical support for patients and families |

| Social Worker involved in care |

| Symptom management and comfort care |

| DNR order in place at time of death |

| Comfort care orders or all meds/orders discontinued at time of death |

| Patient died in the setting of full support |

| Pain assessment recorded |

| Shortness of breath assessment recorded |

| Agitation assessment recorded |

| Anxiety assessment recorded |

| Confusion assessment recorded |

| Presence of pain recorded |

| Presence of shortness of breath recorded |

| Presence of agitation recorded |

| Presence of anxiety recorded |

| Presence of confusion recorded |

| CPR performed in the last 24 hours |

| CPR performed in the last hour |

| Tube feeding orders withdrawn |

| TPN orders withdrawn |

| IVF orders withdrawn |

| Vasopressors withdrawn |

| Ventilation orders discontinued |

| Spiritual support for patients and families |

| Spiritual Care involved in care |

| Documentation of spirituality addressed |

Abbreviations: DPOAHC: durable power of attorney for health care, DNR: do not resuscitate, CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, TPN: total parenteral nutrition, IVF: intravenous fluids

Statistical Analyses

We compared a number of demographic characteristics and processes of care variables between respondents and non-respondents including age, gender, race/ethnicity, hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay, and discharge service. We used t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables.

For all analyses, we used two outcome variables: 1) the family assessed QODD-22 total score; and 2) scores on the single item QODD-1, “Overall, how would you rate the quality of your loved one’s dying?” We used non-parametric analyses because the QODD in this sample did not meet the assumption of a normal distribution. For bivariate analyses, Spearman correlation coefficients were used for ordinal variables, Mann-Whitney tests were used for dichotomous variables and Kruskal Wallis tests were used for the non-ordinal categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05 without correction for multiple comparisons due to the exploratory nature of these analyses. Therefore, the results should be considered hypothesis generating. Potential quality markers identified in the bivariate analysis (p<0.05 for QODD-22 or QODD-1) were then tested separately against each of the outcomes (QODD-22 and QODD-1) with adjustment for potential confounding variables including race/ethnicity, patient and family member gender, patient and family member age, ICU length of stay and the service caring for the patient at the time of death. For this sensitivity analysis, both the QODD-22 and the QODD-1 were modeled as 10-category ordinal categorical outcomes, using a weighted mean- and variance-adjusted least squares estimator because their distributions departed significantly from the normal distribution. Multivariate analysis was done using a probit regression model.

Results

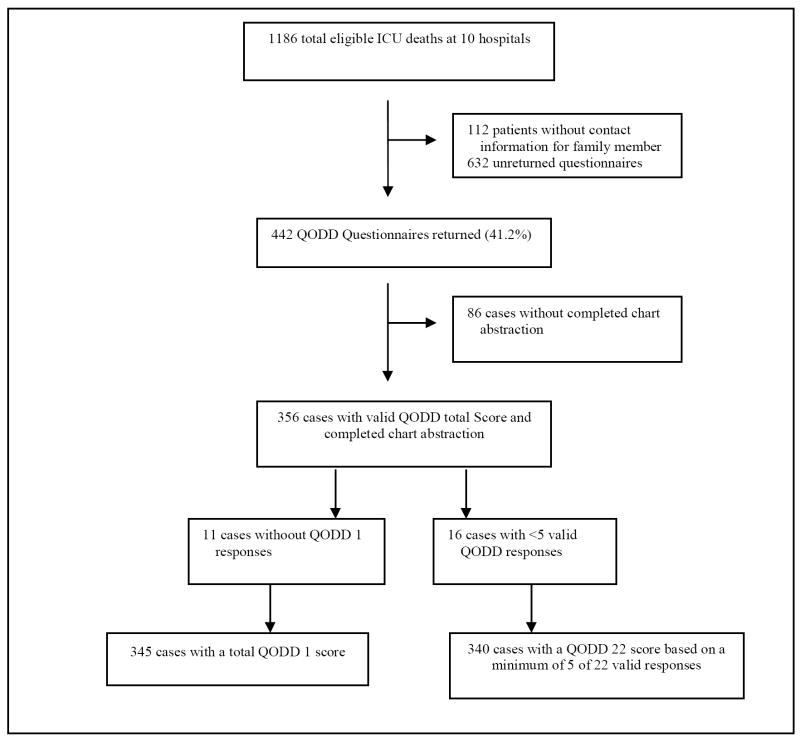

After excluding families for whom there was no contact information, survey packets were sent to 1074 family members of 1186 eligible patients (90.6%). Four hundred forty-two family members returned survey packets (41.2% response rate). Because the study is in progress, charts of some of these patients were not yet abstracted (n=86) and the sample was therefore reduced to 356. Of these 356 patients with usable data, 340 had both chart abstraction data and a valid response for the QODD-1. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Exclusion criteria and identification of 356 cases for analysis.

Demographic characteristics of patients for whom questionnaires were returned and chart abstraction was complete (n=356) were significantly different (p<0.05) from those of patients without returned questionnaires and completed chart abstraction (n=484) in several respects. Patients for whom a questionnaire was returned were more likely to be white (78.1% vs. 59.5%, p <0.001) and had slightly longer ICU stays (2.8 days vs. 2.4 days, p =0.02). Family respondents were younger than patients, with a mean age of 58, and were more likely to be female (67.6%). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients dying in the ICU and QODD respondents

| Characteristic | Study Sample (n=356) | Non-respondents (n=484) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Age (mean± SD) | 70.1 ± 15.9 | 68.1± 16.2 | 0.07 |

| Male Patients (%) | 209(58.7) | 255(52.7) | 0.08 |

| Patient Race (%) | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 278(78.1) | 288(59.5) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 4(1.1) | 4(0.8) | 0.05 |

| Black | 8(2.2) | 42(8.7) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 13(3.7) | 46(9.5) | 0.001 |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 12(2.5) | <0.01 |

| Native American | 2(0.6) | 6(1.2) | 0.20 |

| Other | 1(0.3) | 5(1.0) | 0.15 |

| Hospital LOSa Median (IQR)b | 4 days (2,9 days) | 4 days (1,9 days) | 0.10 |

| ICU LOS Median (IQR)b | 2.8 days (0.9, 7.1 days) | 2.4 days (0.8, 5.8 days) | 0.02 |

| Primary Diagnosis (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Cardiovascular event or illness | 69 (19.4) | 69 (14.3) | |

| Trauma | 41 (11.5) | 29 (6.0) | |

| Sepsis | 37 (10.4) | 53 (11.0) | |

| Respiratory failure or pulmonary illness | 33 (9.3) | 65 (13.4) | |

| Pneumonia | 27 (7.6) | 30 (6.2) | |

| Discharge Service (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Neurology/neurosurgery | 58 (16.3) | 41 (8.5) | |

| Internal medicine | 233 (65.4) | 364 (75.2) | |

| General surgery | 35 (9.8) | 29 (6.0) | |

| Surgical subspecialities | 29 (8.1) | 48 (9.9) | |

| Family Member Age (mean± SD) | 58.5 ± 14.6 | ||

| Male Respondents | 110(32.4) | ||

| Respondent’s relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse/partner | 145(42.6) | ||

| Patient’s child | 118(34.7) | ||

| Patient’s sibling | 23(6.8) | ||

| Patient’s parent | 14(4.1) | ||

| Other relative | 9(2.6) | ||

| Patient’s friend | 5(1.5) | ||

| Other relationship | 17(5.0) |

LOS = length of stay;

IQR = interquartile range.

The mean QODD-22 score was 61.8 (SD 23.8, range 0-100). The median was 64.1, and the interquartile range was 47-80. The distribution of total scores deviated significantly from a normal distribution: significant skew of -0.61 (Z=4.63, p=0.000) and significant Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests for non-normality (p=0.005 and 0.001, respectively). The mean QODD-1 score was 6.9 (SD 3.1, range 0-10). The median was 8.0, and the interquartile range was 5.0-9.0. The distribution of QODD-1 diverged significantly from normality: skew of -0.99 (Z=-7.42, p=.000); probability of less than 0.001 associated with both the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests for non-normality. The Spearman ρ between QODD-22 and QODD-1 was 0.74 (p<0.001).

Table 3 shows the results of bivariate analyses identifying factors that were associated with the QODD-22 and the QODD-1. Demographic characteristics associated with the QODD-22 included patient and respondent age. In both cases there was a significant, though small, increase in total QODD scores with increasing age. Male patients tended to have higher family scores on the QODD-22 than female patients. We found no correlation between the QODD-22 and hospital site, discharge service, hospital length of stay, or ICU length of stay. For the QODD-1, similar findings were demonstrated for associations with respondent age and patient gender; additional associations were found with higher single item ratings among female respondent and patients identified as white/non-hispanic.

Table 3.

Results of tests for univariate associations between patient and respondent characteristics, potential quality markers according to end-of-life care domain and family QODD-22 scores and the single item QODD-1

| Dichotomous Variable | Na (340) | QODD-22 score, Mean (SD) | p valueb | Na (335) | QODD-1 score, Mean (SD) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Patient Race | 0.30 | 0.02 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 262 | 62.6(23.6) | 261 | 7.1(3.1) | ||

| Non-white | 27 | 56.9(25.7) | 25 | 5.4(3.7) | ||

| Patient Gender | 0.05 | 0.03 | ||||

| Male | 200 | 63.8(23.5) | 198 | 7.2(3.0) | ||

| Female | 140 | 58.9(24.0) | 137 | 6.5(3.3) | ||

| Family Member’s Gender | 0.18 | 0.04 | ||||

| Male | 110 | 60.1(21.7) | 107 | 6.7(2.8) | ||

| Female | 221 | 62.5(25.0) | 221 | 7.0(3.3) | ||

| Other Categorical Variable | QODD-22 score, Mean (SD) | p valuec | QODD-1 score, Mean (SD) | p valuec | ||

| Discharge service | 0.11 | 0.07 | ||||

| Medicine or Medical Subspeciality | 224 | 61.9(23.3) | 222 | 7.0(3.0) | ||

| General Surgery | 32 | 56.1(26.6) | 32 | 6.2(3.8) | ||

| Surgical Subspeciality | 28 | 54.5(28.6) | 27 | 5.9(3.9) | ||

| Neurology/Neurosurgery | 55 | 67.9(20.0) | 53 | 7.9(2.4) | ||

| Recruitment site | 340 | 0.40 | 335 | 0.13 | ||

| 10 hospitals | ||||||

| Respondent’s relationship to patient | 331 | 0.87 | 328 | 0.43 | ||

| Seven categories | ||||||

| Ordinal Variable | QODD -22 score, ρ | p valued | QODD-1 score, ρ | p valued | ||

| Respondent age | 326 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 323 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | 329 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 327 | -0.07 | 0.21 |

| Six ordinal categories | ||||||

| Patient age | 340 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 335 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 340 | -0.02 | 0.78 | 335 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 340 | -0.08 | 0.14 | 335 | -0.02 | 0.67 |

| Patient and family centered decision making | ||||||

| Presence of living will | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 144 | 64.3(22.0) | 140 | 7.4(2.9) | ||

| No | 122 | 57.5(25.5) | 118 | 6.3(3.3) | ||

| Documentation of DPOAHC | 0.06 | 0.13 | ||||

| Yes | 129 | 64.9(22.0) | 125 | 7.3(2.9) | ||

| No | 71 | 58.1(24.8) | 71 | 6.3(3.6) | ||

| Patient’s wish to withdraw life support documented | 0.000 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 62 | 70.4(21.3) | 61 | 8.1 (2.3) | ||

| No | 272 | 60.1(23.5) | 268 | 6.7(3.2) | ||

| Patient’s opinions documented | 0.14 | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 156 | 63.9(23.1) | 154 | 7.4(2.9) | ||

| No | 178 | 60.4(23.6) | 175 | 6.6(3.2) | ||

| Family present at death | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||

| Yes | 244 | 63.4(24.2) | 242 | 7.1(3.1) | ||

| No | 73 | 55.9(23.2) | 73 | 6.4(3.2) | ||

| Communication within the team and with patients and families | ||||||

| Documentation of a family conference occurring in the first or last 72 hours | 0.77 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 312 | 62.0(23.6) | 306 | 7.1(3.1) | ||

| No | 22 | 62.2(20.2) | 23 | 5.4(3.0) | ||

| Documentation of discord Between Family and MD | 0.06 | 0.74 | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 52.4(22.7) | 17 | 6.8(3.2) | ||

| No | 317 | 62.5(23.4) | 312 | 7.0(3.1) | ||

| Symptom management and comfort care | ||||||

| Pain assessment recorded in the last 24hours | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 300 | 62.8(23.1) | 295 | 7.1(3.0) | ||

| No | 40 | 54.3(27.8) | 40 | 5.8(3.6) | ||

| CPR performed in the last hour | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 52.7(22.7) | 29 | 5.6(3.3) | ||

| No | 302 | 63.0(23.3) | 299 | 7.1(3.1) | ||

| Comfort care orders in place, or all orders discontinued | 0.41 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 210 | 62.7(24.0) | 209 | 7.4(3.0) | ||

| No | 127 | 60.8(23.3) | 123 | 6.4(3.1) | ||

| Patient died in the setting of full support | 0.13 | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 58.1(25.0) | 63 | 6.0(3.3) | ||

| No | 271 | 63.0(23.3) | 269 | 7.2(3.0) | ||

| Tube feeding orders withdrawn in the last 5 days | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 64.5(22.1) | 69 | 7.6(2.9) | ||

| No | 42 | 56.7(20.8) | 39 | 6.4(3.3) | ||

| Intravenous fluids withdrawn in the last 5 days | 0.94 | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 100 | 63.0(21.3) | 102 | 7.6(2.8) | ||

| No | 155 | 62.5(23.0) | 152 | 6.7(3.2) | ||

| Vasopressors withdrawn in the last 5 days | 0.36 | 0.06 | ||||

| Yes | 106 | 62.5(24.4) | 107 | 7.1(3.2) | ||

| No | 84 | 59.5(24.1) | 80 | 6.1(3.4) | ||

| Mechanical Ventilation withdrawn in the last 5 days | 0.75 | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 182 | 61.2(24.4) | 185 | 7.2(3.1) | ||

| No | 92 | 60.5(23.7) | 89 | 6.4(3.2) | ||

Bold values indicate significance at p = 0.05 for either QODD-22 or QODD-1.

deviations from the total N reflect missing data for the predictor

p values for associations with dichotomous predictors were assessed using Mann-Whitney tests;

p values for associations involving other categorical predictors were assessed using Kruskal Wallis tests;

p values for comparisons involving ordinal predictors were determined using Spearman correlation coefficient

Potentially modifiable predictors of the QODD-22 score that were documented in the medical record and were associated with higher scores included: 1) the presence of a living will; 2) documentation of discussions of a patient’s wish to withdraw life support during a family conference; 3) presence of a family member at the time of death; and 4) withdrawal of tube feeding for the purpose of withdrawing life support.(Table 3) CPR in the last hour of life was associated with a lower QODD-22.

All but one of the variables that were associated with the QODD-22 score were also associated with the QODD-1 (Table 3). This one variable (presence of family at the time of death) showed a trend in the same direction but did not achieve statistical significance. There were several additional variables associated with the QODD-1 that were not associated with the QODD-22. Whereas only the withdrawal of tube feeding was associated with the QODD-22, the withdrawal of two other interventions (intravenous fluids and mechanical ventilation) was associated with the QODD-1 (Table 3). Documentation of the patient’s treatment preferences, documentation of a family conference, documentation of pain assessment and the presence of comfort care orders at the time of death all predicted more positive responses to the QODD-1, but not higher QODD-22 scores. The occurrence of death in the setting of full life support predicted more negative responses to the QODD-1

In the multivariate analyses, four variables were found to be independent predictors of the QODD-22 score after controlling for demographic variables (Table 4). Significant independent predictors of higher QODD-22 scores included: 1) presence of family members at the time of death; 2) documentation of the patient’s wish to withdraw life support in a family conference; 3) documentation of pain assessment; and 4) no CPR in the last hour of life.

Table 4.

Results of multivariate regression analysesa, testing associations between potential quality markers and family QODD-22 scores and the single item QODD-1

| Nb (340) |

β (SE) | QODD-22c Z |

p | 95% CI | Nb (335) |

β (SE) | QODD-1d Z |

p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient and family centered decision making | ||||||||||

| Presence of living will | 222 | 0.107 (0.155) | 0.689 | <0.50 | -0.197, 0.411 | 217 | 0.286 (0.162) | 1.765 | <0.08 | -0.032, 0.604 |

| Documentation of DPOAHC | 175 | 0.234 (0.180) | 1.300 | <0.20 | -0.119, 0.588 | 172 | 0.220 (0.192) | 1.147 | <0.26 | -0.156, 0.596 |

| Family present at death | 257 | 0.496 (0.164) | 3.016 | <0.003 | 0.174, 0.818 | 258 | 0.418 (0.171) | 2.439 | <0.02 | 0.082, 0.753 |

| Patient’s opinions documented | 271 | 0.199 (0.132) | 1.509 | <0.14 | -0.059, 0.458 | 269 | 0.288 (0.138) | 2.086 | <0.04 | 0.017, 0.558 |

| Patient’s wish to withdraw life support documented | 271 | 0.478 (0.186) | 2.574 | <0.02 | 0.114, 0.841 | 269 | 0.440 (0.202) | 2.186 | <0.03 | 0.046, 0.835 |

| Communication within the team and with patients and families | ||||||||||

| Documentation of a family conference occurring in the first or last 72 hours | 271 | -0.088 (0.297) | -0.297 | <0.77 | -0.669, 0.493 | 269 | 0.596 (0.317) | 1.878 | <0.07 | -0.026, 1.218 |

| Documentation of discord Between Family and MD | 271 | -0.389 (0.349) | -1.114 | <0.27 | -1.073, 0.295 | 269 | 0.204 (0.329) | 0.621 | <0.54 | -0.440, 0.849 |

| Symptom management and comfort care | ||||||||||

| Pain assessment recorded in the last 24 hours | 277 | 0.450 (0.213) | 2.108 | <0.04 | 0.032, 0.868 | 275 | 0.428 (0.249) | 1.721 | <0.09 | -0.059, 0.916 |

| CPR performed in the last hour | 271 | -0.538 (0.225) | -2.394 | <0.02 | -0.978, -0.097 | 268 | -0.455 (0.269) | -1.689 | <0.10 | -0.983, 0.073 |

| Comfort care orders in place, or all orders discontinued | 276 | 0.117 (0.134) | 0.878 | <0.38 | -0.144, 0.379 | 274 | 0.402 (0.138) | 2.912 | <0.01 | 0.131, 0.672 |

| Patient died in the setting of full support | 276 | -0.104 (0.148) | -0.706 | <0.49 | -0.394, 0.185 | 274 | -0.395 (0.163) | -2.428 | <0.02 | -0.714, -0.076 |

| Tube feeding orders withdrawn in the last 5 days | 94 | 0.509 (0.268) | 1.901 | <0.06 | -0.016, 1.033 | 93 | 0.520 (0.267) | 1.951 | <0.06 | -0.002, 1.043 |

| Intravenous fluids withdrawn in the last 5 days | 214 | -0.037 (0.158) | -0.232 | <0.82 | -0.346, 0.272 | 214 | 0.333 (0.168) | 1.983 | <0.05 | 0.004, 0.661 |

| Vasopressors withdrawn in the last 5 days | 156 | 0.254 (0.184) | 1.379 | <0.17 | -0.107, 0.616 | 156 | 0.310 (0.175) | 1.771 | <0.08 | -0.033, 0.653 |

| Mechanical Ventilation withdrawn in the last 5 days | 222 | 0.058 (0.150) | 0.389 | <0.70 | -0.236, 0.353 | 225 | 0.295 (0.156) | 1.895 | <0.06 | -0.010, 0.600 |

Each quality marker was tested separately, with simultaneous adjustment for race/ethnicity of patient, gender of patient and family member, age of patient and family member, hospital length of stay, and discharge service (three indicator variables designating general surgery, surgical subspecialty, and neurology/neurosurgery).

deviations from the total N reflect missing data for the predictor

QODD-22 was recoded into 10 categories (0-15, 15-25, 25-35, 35-45, 45-55, 55-65, 65-75, 75-85, 85-95, 95-100) and modeled as an ordinal categorical outcome, using a mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator.

QODD-1 was recoded into 10 categories (0-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) and modeled as an ordinal categorical outcome, using a mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator.

Multivariate analyses using the QODD-1 yielded slightly different results. The documentation of pain assessment and no CPR in the last hour failed to reach statistical significance. However, family presence at the time of death and documentation of the patient’s wishes to withdraw life support (based on clinician communication with the patient) were similarly significant predictors. New significant predictors of the QODD-1 were: 1) documentation of patient’s opinions in a family conference, referring to the indirect reference to the patient’s wishes by a family member; 2) the presence of comfort care orders or orders to withdraw all treatments; and 3) the withdrawal of intravenous fluids for the purpose of withdrawing support. Dying in the setting of full support was associated with lower QODD-1 scores.

Discussion

Use of the medical record to identify “quality markers” for predicting the QODD

This study suggests that there are data within the medical record related to previously identified domains of end-of-life care that are associated with families’ assessments of the quality of dying. Recent efforts have been made to develop and pilot medical record-based quality measures to assess and improve palliative care in the ICU (28), but no prior studies have examined the correlation of such measures with patients’ or families’ assessments of care. While the medical record falls far short of capturing the entire complexity of end of life care and decision making, we did find that several previously-defined domains identified as important to the quality of end-of-life care were represented in a large proportion of charts. These domains included “patient and family centered decision making,” “communication within the team and with patients and families,” and “symptom management and comfort care.” We also identified variables related to “emotional and practical support for patients and families” and “spiritual support for patients and families” (Table 1). While our results may seem intuitive within the context of these domains, they serve as an important link between a conceptual framework and the methodology of measuring and improving outcomes in end-of-life care.

Implications of Predictors of the QODD

We report the associations of predictors with both the QODD-22 score and the single item QODD-1 in our results. There were a total of five variables associated with the QODD-22 score and 11 variables associated with the QODD-1. There was a high degree of agreement between the two outcome measures (importantly, the single overall rating item of the QODD-1 is not contained in the QODD-22). Four of the five variables associated with the QODD-22 were also associated with the QODD-1. It may be that the single item QODD-1 could replace the 22-item QODD-22, but it is important to note that this single item was rated after family members completed the 22 items of the QODD-22. By identifying experiences associated with dying and allowing respondents to consider and rate these experiences, the QODD-22 may set the frame that then allows respondents to derive a more accurate or thoughtful overall rating of their loved one’s dying experience. As noted previously, the responsiveness of the QODD has not been established. However, using the method of Cohen as an estimate of effect size we found that the differences identified in our bivariate analyses (p<0.05) represented a modest effect size (0.26< d <0.56). (29, 30) Further research is needed to determine the comparative measurement characteristics of the QODD-22 and the QODD-1.

The fact that medical record documentation of the presence of a living will and the patient’s wish to withdraw life support were associated with higher QODD scores may reflect the positive effects associated with planning for end-of-life care by these patients and their families. Our findings support an emphasis on discussing end-of-life care preferences with patients prior to critical illness and documenting their wishes and provide some evidence for a benefit of living wills despite the fact that living wills have not been shown to change the aggressiveness of care provided to patients.(31, 32) If these findings are confirmed with further study, measures of preparation and planning for end-of-life care could be used in evaluating the quality of end-of-life care.

The presence of a family member at the time of death was strongly associated with the QODD-22 score. Similarly, a study of nurse-assessed QODD scores also found that the presence of a family or staff member at the time of death was associated with higher nurse ratings of the QODD.(33) This finding adds to growing data that increased access of family members to patients at the time of death is an important aspect of improving end-of-life care.(33,34,35,36)

The performance of CPR in the last hour of life was associated with lower QODD scores. This finding is consistent with prior work demonstrating a lower nursing assessment of the QODD when CPR was performed in the last eight hours of life.(33) Efforts to address this with patients and their families should be made early in the course of critical illness to avoid CPR in cases in which the intervention is unlikely to alter the patient’s outcome.

Interestingly, we found that the documentation of pain assessment in the last 24 hours of life was associated with a higher QODD-1 score (p = 0.02) while the presence of pain was not. Adequate pain control is a primary goal shared by patients, families, and providers in the care of critically ill patients.(24,37) Our results suggest that documenting pain assessment is associated with improvement in the family’s impression of the quality of the dying experience, a finding supported by previous studies. (6,38,39,40)

Documentation of the discontinuation of tube feeding was the only intervention withdrawal variable that was significantly associated with a higher QODD-22 score. Interestingly, the withdrawal of two other interventions, mechanical ventilation and IV fluids, were associated with a higher rating on the QODD-1.(Table 3) Asch et al. have published observational data demonstrating that interventions are often withdrawn in a distinct sequence with interventions characterized as more artificial, scarce, or expensive withdrawn first.(41) In that study, tube feeding was consistently the last intervention withdrawn. Thus, it is possible that the withdrawal of tube feeding in our study was positively correlated with the QODD-22 because it represented the complete transition to comfort-centered care.

Our findings are in alignment with previously defined domains of end-of-life care (13) and all identified associations are in the direction predicted by conceptual models of end-of-life care such as the one proposed by the Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine.(37) The importance of this study is that it serves as a link between this conceptual framework, family assessments of the quality of care and a readily available source of data in the medical record. This is an important step in the process of improving the delivery of end-of-life care which will hinge, as others have noted, on identifying “valid, reliable, acceptable, efficient, and responsive measures” of quality in this setting. (42)

Limitations

We limited the number of variables to those which we felt were in the causal pathway of quality care. Nonetheless, the number of variables analyzed does expose this analysis to an increased risk of Type I errors with the potential for spurious associations. Given the lack of validated “quality markers” and the exploratory nature of this investigation, we feel that it was appropriate to err on the side of including, rather than limiting, variables by using an inclusive threshold of p < 0.05. With the identification of these potential quality markers, further studies will be needed to confirm these associations in other populations. A second limitation of this study is that it was conducted in one region of the United States, the Pacific Northwest. Research has shown that there may be significant cultural differences in the way individuals and families cope with dying and death.(43,44,45) Our study population was largely white (78%) which raises the question as to whether these results are generalizable to other populations. In addition, of eligible decedents for whom we had chart abstraction, our response rate with valid QODD responses was only 41.2%. This low response rate does not affect the internal validity of the associations between chart-based predictors and the QODD score, but caution must be exercised in generalizing these results to all patients dying in the ICU. Third, because this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot assume that the associations identified in this study represent causal relationships. Future studies will be needed to confirm and determine the nature of these relationships. Finally, the use of family reports as a proxy for the patient’s experience of the quality of end-of-life care is another unavoidable limitation. Despite these limitations, we seek here to test the consistency of the conceptual model upon which the QODD is built. The fact that all significant associations were in the direction that we would predict based on preexisting conceptual models adds support to the use of these variables as quality markers.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified potential chart-based markers of quality of end-of-life care in the ICU associated with higher family assessments of quality of dying and death scores. These chart based variables may serve as potential targets for measuring and improving the quality of end-of-life care in the ICU and may have potential as chart based “quality markers” for end-of-life care in the ICU. Future research should focus on determining if these markers are predictive of other measures of the quality of end-of-life care such as nurse and physician assessments of the quality of care, and to what extent these markers are sensitive to interventions aimed at improving the care of patients who die in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by the dedication and hard work of those involved in the End-of-life research program at the University of Washington. Special thanks is due to those who abstracted data from patient charts and especially to the families who participated in this study so that we might improve the way we provide care in the future.

Funding: This manuscript was supported by an RO1 grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (5 RO1 NR-05226) and a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1163–1167. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.4.9801108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayes RL, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Knaus WA. Variations in the use of do-not-resuscitate orders in ICUs: findings from a national study. Chest. 1996;110:1332–1339. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.5.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrand E, Robert R, Ingrand P, Lemaire F. Withholding and withdrawal of life support in intensive-care units in France: a prospective survey. Lancet. 2001;357:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenan SP, Busche KD, Chen LM, Esmail R, Inman KJ, Sibbald WJ. Withdrawal and withholding of life support in the intensive care unit: a comparison of teaching and community hospitals. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:245–251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1996;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, Kuteifan K, Badet M, Asfar P, Jaber S, Chaqnon JL, Renault A, Robert R, Pochard F, Herve C, Brun-Buisson C, Duvaldestin P. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1310–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-752OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, Canoui P, Le Gall JR, Schlemmer B. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3044–3049. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocker GM, Cook DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Pichora D, Dodek PM, Conrad W, Kutsoqiannis DL, Heyland DK. Canadian nurses’ and respiratory therapists’ perspectives on withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2005;20:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook D, Rocker G, Heyland D. Dying in the ICU: strategies that may improve end of life care. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:266–272. doi: 10.1007/BF03019109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: Perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127:175–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, Levy M, Danis M, Nelson J, Solomon MZ. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhoff KT, Anumandla PR, Foth KT, Lues SN, Gibertson-White SH. Documentation on withdrawal of life support in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2004;13:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall RI, Rocker GM. End-of-life care in the ICU: Treatments provided when life support was or was not withdrawn. Chest. 2000;118:1424–1430. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.5.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke EB, Luce JM, Curtis JR, Danis M, Levy M, Nelson J, Solomon MZ. A content analysis of forms, guidelines, and other materials documenting end-of-life care in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2004;19:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dresselhaus TR, Luck J, Peabody JW. The ethical problem of false positives: a prospective evaluation of physician reporting in the medical record. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:291–294. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.5.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, Nielsen EL, Braungardt T, Rubenfeld GD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Integrating palliative and critical care: description of an intervention. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S380–S387. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237045.12925.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, De Ruiter C, Curtis JR. Using the Medical Record to Evaluate the Quality of End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:A217. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:717–726. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick DL, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen E, McCown E. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:410–415. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_2-200309021-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Osborne M, Engelberg RA, Ganzini L. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:306–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, Ganzini L, Curtis JR. Quality of dying in the ICU: Ratings by family members. Chest. 2005;128:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asch DA, Shea JA, Jedrziewski MK, Bosk CL. The limits of suffering: Critical care nurses’ views of hospital care at the end of life. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1661–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: Patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, Pronovost PJ. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: a practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:264–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people’s published data: General procedures for research consumers. Pyschological Methods. 1996;1:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandrevala T, Hampson SE, Daly T, Arber S, Thomas H. Dilemmas in decision-making about resuscitation-a focus group study of older people. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1579–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tonelli MR. Pulling the plug on living wills. A critical analysis of advanced directives. Chest. 1996;110:816–822. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodde NM, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Factors associated with nurse assessment of the quality of dying and death in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1648–1653. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133018.60866.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: Observations of patients, families and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierson CM, Curtis JR, Patrick DL. A good death: A qualitative study of patients with advanced AIDS. AIDS Care. 2002;14:587–598. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truog RD, Cist AFM, Brackett SE, Burns JP, Curley MA, Danis M, DeVita MA, Rosenbaum SH, Rothenberg DM, Sprung CL, Webb SA, Wlody GS, Hurford WE. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: the Ethics committee of the society of critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2332–2348. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson JE, Meier D, Oei EJ, Nierman DM, Senzel RS, Manfredi PL, Davis SM, Morrison RS. Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:277–282. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellershaw J, Smith C, Overill S, Walker SE, Aldridge J. Care of the dying: setting standards for symptom control in the last 48 hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:12–17. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puntillo KA. Pain experience of intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung. 1990;19:525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asch DA, Faber-Langendoen K, Shea JA, Christakis NA. The sequence of withdrawing life sustaining treatment from patients. Am J Med. 1999;107:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mularski RA. Defining and measuring quality palliative and end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S309–S316. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000241067.84361.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodlin SJ, Zhong Z, Lynn J, Teno JM, Fago JP, Desbiens N, Connors AF, Jr, Wenger NS, Phillips RS. Factors associated with use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in seriously ill hospitalized adults. JAMA. 1999;282:1333–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shrank WH, Kutner JS, Richardson T, Mularski RA, Fischer S, Kagawa-Singer M. Focus group findings about the influence of culture on communication preferences in end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:703–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins HS, Shepherd KJ, Cortez JD, Hazuda HP. Exploring chronically ill seniors’ attitudes about discussing death and postmortem medical procedures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:895–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]