Abstract

The association between racial and ethnic discrimination and psychological distress was examined among 2,047 Asians (18 to 75 years of age) in the National Latino and Asian American Study, the first-ever nationally representative study of mental health among Asians living in the United States. Stratifying the sample by age in years (i.e., 18 to 30, 31 to 40, 41 to 50, 51 to 75) and nativity status (i.e., immigrant vs. U.S.-born), ethnic identity was tested as either a protective or exacerbating factor. Analyses showed that ethnic identity buffered the association between discrimination and mental health for U.S.-born individuals 41 to 50 years of age. For U.S.-born individuals 31 to 40 years of age and 51 to 75 years of age, ethnic identity exacerbated the negative effects of discrimination on mental health. The importance of age and immigrant status for the association between ethnic identity, discrimination, and well-being among Asians in the United States is discussed.

Keywords: racial discrimination, ethnic identity, psychological distress

It is an unfortunate reality that discrimination based on race and ethnicity is a normative experience for Asians in the United States (Goto, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2002; Noh & Kaspar, 2003). Even more disturbing is that research consistently finds that discrimination is associated with poorer mental and physical health (Bhui et al., 2005; Brody et al., 2006; Rumbaut, 1994; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Despite discrimination's pernicious consequences, recent studies suggest that its harmful effects can be moderated by an individual's ethnic identification (Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999). In this study, we extend this line of research by examining the influence of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and mental health among a nationally representative sample of Asian adults living in the United States. Specifically, we investigate whether these associations vary by one's life-stage context, as indicated by age and nativity.

The following literature review discusses research examining the moderating effects of ethnic identity, both as a buffer for, and an exacerbator of, the effects of discrimination on mental health. Next, age and its association with ethnic identity and discrimination are reviewed, with specific attention to how ethnic identity might influence the association between discrimination and health. Finally, the effects of nativity on ethnic identity and discrimination are reviewed, again with the goal of examining how ethnic identity might buffer or exacerbate the effects of discrimination on health.

Ethnic Identity, Discrimination, and Mental Health

Research on the influence of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and mental health is equivocal (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Mossakowski, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Williams, Spencer, & Jackson, 1999). As a multidimensional construct, ethnic identity has been measured in many ways (Phinney, 1992; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997; Umana-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bamaca-Gomez, 2004). For example, Phinney and her colleagues have focused on dimensions of ethnic identity achievement and affirmation (Phinney, 1992). Sellers and his colleagues have examined the significance and meaning of racial identity through the dimensions of centrality, private regard, and public regard (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). Umana-Taylor and her colleagues (2007) have focused on identity exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Moreover, researchers have found that different dimensions of ethnic identity are related to outcomes in different ways. For example, in a sample of Korean Americans, ethnic pride was found to buffer the effects of discrimination (Lee, 2005). However, the current study focuses primarily on ethnic identity centrality, which is the extent to which ethnic identity is a core and significant aspect of one's overall identity (Sellers et al., 1997). Focusing on ethnic centrality, there are two equally plausible hypotheses for how ethnic identity should affect the association between discrimination and health. Specifically, one might expect that if ethnic identity is a protective resource, then it may serve to buffer the negative effects of discrimination. On the other hand, one might also expect that an individual reporting discrimination based on an important and central aspect of one's identity would report increased negativity. Indeed, a review of the literature on the influence of ethnic identity centrality on the association between discrimination and health finds support for both a buffering and exacerbating effect of ethnic identity.

The Buffering Hypothesis

The first perspective views ethnic identity as a mechanism that protects against, or buffers a person from, the negative effects of discrimination (Phinney, 1990, 1996; Rumbaut, 1994). Discrimination, considered to be biased actions against an individual because of his/her group membership, may lead to psychological distress through assaults on one's sense of self-worth, self-concept, and belonging (Harrell, 2000; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). In addition, discrimination may induce stress and cause socioeconomic deprivation, which, in turn, may lead to distress and other forms of morbidity (Krieger, 1999).

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 2001) provides a possible explanation for why ethnic identity might buffer the effects of discrimination. According to this theory, individuals choose from an array of possible social identity groups; and, once those groups are chosen, individuals focus on the positive aspects of their in-group, which helps to bolster their own esteem. More importantly, the more an individual identifies with a particular social group, the more invested he or she is in stressing the positive attributes of that group. Applied to ethnic identity, it then follows that individuals who report that ethnic identity is more important to their overall identity would be more committed to feeling good about their group membership even in the face of discrimination. If discrimination induces distress through an attack on one's self-concept, then ethnic identity might moderate discrimination by counterbalancing such an assault. As such, one would expect individuals with a strong sense of ethnic identity to be buffered against the potential psychological detriments of ethnic discrimination.

Indeed, research points to the protective function of ethnic identity for the mental health consequences of racial and ethnic discrimination. For example, Mossakowski (2003) found that having a strong sense of ethnic identity buffered the negative impact of racial and ethnic discrimination on depressive symptoms among Filipino Americans 18 to 65 years of age. Ethnic centrality has also been found to buffer the effects of racial discrimination, such that African American adolescents reporting low and moderate centrality reported a positive association between experiences of discrimination and distress, whereas their counterparts who reported high centrality did not (Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003). Similar patterns have been observed for African American college students, discrimination being associated with increased anxiety, stress, and depression for individuals reporting low and moderate centrality but not for those reporting high centrality (Neblett, Shelton, & Sellers, 2004). Taken together, studies spanning adolescence to late adulthood find that ethnic identity buffers the negative psychological impact of discrimination.

The Exacerbating Hypothesis

If ethnicity is a central component of one's identity, it is equally plausible that having a strong ethnic identity may actually exacerbate the effects of discrimination, resulting in a greater negative impact on mental health. Self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) suggests that people should be more in tune with environmental cues that are relevant to an important aspect of their identity; experiences of racial discrimination may be such a cue relevant to their ethnic identity. Indeed, research suggests that African American young adults and adolescents who report strong racial centrality are also more likely to report experiences of racial discrimination (Neblett et al., 2004; Sellers et al., 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). Similar patterns have also been observed among a sample of Asian, Latino, and African American college students; highly identified individuals appear more responsive to subtle forms of discrimination (Operario & Fiske, 2001). A possible explanation for this observation comes from research that finds African Americans for whom race was highly central were also more likely to attribute an ambiguous situation as racially discriminatory (Shelton & Sellers, 2000).

Not only are individuals who have higher ethnic centrality more likely to report ethnic and racial discrimination, but the exacerbating hypothesis suggests that they should also react more negatively to such events. Examining empirical support for the exacerbating hypothesis, several studies find that ethnic identity exacerbates the negative impact of discrimination. For instance, McCoy and Major (2003) found that college students who identified more strongly with being Latino reported more negative affect after reading about the unfair treatment of Latinos compared to participants who reported a weaker ethnic identification. Similar observations have been made among Asian, African American, and Latino students, strong identification with one's ethnic group being associated with increased vulnerability to experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination (Operario & Fiske, 2001). In a study of Southeast Asian adult refugees (mean age, 41 years), ethnic centrality was found to strengthened the negative association between discrimination and depression (Noh et al., 1999).

Taken together, ethnic identity seems to operate both to buffer and exacerbate the negative effects of discrimination across a variety of ethnic groups spanning adolescence to late adulthood. Perhaps one of the reasons why it has been difficult to reconcile these seemingly opposing findings is that each study has focused on different samples across a wide age range. Research among Asians living in the United States has found that discrimination and morbidity appear to vary by context (Gee, 2002; Gee, Spencer, Chen, Yip, & Takeuchi, 2007). Therefore, the current study extends this research by simultaneously exploring the effects of age and nativity as a developmental context for these relationships.

Age

Discrimination and Age

The changing association between discrimination and age may also play a role in whether ethnic identity will serve to buffer or exacerbate the effects of discrimination. According to the biopsychosocial model, discrimination may operate as an acute stressor that leads to an acute illness as well as a chronic stressor that may contribute to allostatic load and chronic illness (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). The chronic stressor model suggests that discrimination may have stronger effects as individuals age because of greater accumulation of allostatic load (Harrell, 2000; Neblett, Shelton, & Sellers, 2004). In addition, some research suggests that an unequal burden of stressors among racial minorities may weather away protective resources and contribute to allostatic load among racial minorities (Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006). Moreover, some research finds that racial discrimination appears to decrease with age, suggesting that the association between discrimination and health over time might be more complex than anticipated (Adams & Dressler, 1988; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999). Research on psychological reactivity to stress finds that perhaps even more important than the frequency of stressors is the way in which individuals appraise and cope with stressors (Lazarus & DeLongis, 1983). In other words, one's subjective reaction to stress may be more influential for psychological outcomes. In fact, scholars have employed a stress and coping framework to understanding the psychological implications of racial and ethnic discrimination (Umana-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). While there is little research on how these specific associations vary over the life span, research on stress reactivity finds that older individuals may seem less reactive to stress because they have developed better coping strategies over time (Almeida & Horn, 2004). Therefore, it is possible that older adults may show less psychological reaction to racial and ethnic discrimination.

Ethnic Identity and Age

Developmental psychologists have discussed the importance of identity development across the life span and its implications for mental health (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001; Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966, 2002; Phinney, 1990). It has also been theorized that ethnic identity changes over the course of one's life with identity exploration beginning in adolescence and culminating in adulthood (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966, 2002). More recently, Cross and Fhagen-Smith (2001) have focused specifically on racial identity development across the life span. In each of these approaches, adolescents are beginning the process of identity exploration and therefore have a less well-developed sense of self, whereas adults have formed an identity and therefore have a clearer, more complex sense of the self. Consistent with such developmental models, research finds that adults are more likely to report having searched for, and committed to, a sense of ethnic identity compared to adolescents (Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). Yet, it has also been acknowledged that even after one has formed a well-developed identity as an adult, normative life events (e.g., marriage, death of a parent), referred to as encounters (Cross, 1991), can trigger a new identity search. Indeed, as people age, they experience changes in social roles (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Kessler, Mickelson, & Walters, 2004; Wethington, Kessler, & Pixley, 2004), which may be associated with the development of more complex ethnic identities over time.

Because the content and stability of ethnic identity has been found to vary over the life span (Yip et al., 2006), it is important to consider the influence of age when examining how ethnic identity affects the relationship between discrimination and mental health. For example, it seems possible that developmental periods that are more likely to be associated with stability of ethnic identity (e.g., middle adulthood) are more likely to find ethnic identity as a buffer for discriminatory experiences. By the same token, periods that are associated with life events that may be considered “encounters” (e.g., parenthood in early adulthood, retirement in late adulthood) may be more likely to observe an exacerbating effect. In other words, the relative instability of one's identity during this developmental period may make it more likely that a strong identification with one's ethnicity has a more negative impact on psychological well-being.

Nativity Status

Ethnic Identity and Nativity Status

Where one is born has also been found to be an important consideration for how and when one develops a sense of ethnic self (Rumbaut, 1994). In a study of 5,000 immigrant adolescents, Rumbaut found that adolescents born outside the United States were more likely to describe their ethnic identity using a label referring to their national origin (43%) compared to adolescents born in the United States to immigrant parents (11%). It seemed that adolescents born in the United States showed a preference for hyphenated-American labels (49%) compared to adolescents born overseas (32%). Similar patterns have been observed among immigrants of Mexican and Chinese backgrounds (Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005). This pattern has been interpreted as evidence for a gradual assimilation and acculturation into United States society for individuals of latter generations. In fact, research on the effects of acculturation for coping with ethnic and racial discrimination finds that Koreans living in Canada who reported feeling more acculturated were better equipped to cope with the negative effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms (Noh & Kaspar, 2003). In the current study, we examined the effect of nativity status and ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and health. Specifically, it seems plausible that more recent immigrants may report an exacerbating effect of ethnic identity because research suggests that their ethnicity is so central to their identity.

Nativity Status and Discrimination

In addition, nativity has been observed to make a difference in how often Asians report being the target of racial and ethnic discrimination. For example, Kuo (1995) found that individuals born in the United States were more likely to report experiencing discrimination compared to their counterparts who were born outside of the United States. For individuals new to the United States, discrimination has been found to contribute to acculturative stress, which, in turn, has been found to be associated with increased depressive symptoms (Salgado de Snyder, 1987). Among Mexican immigrants, more acculturated individuals report higher frequency of discrimination; however, among Mexican individuals born in the United States, the pattern is reversed (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000). With respect to the buffering and exacerbating hypotheses, because more recent immigrants are less likely to report being the target of discrimination, they may be more likely to report an exacerbating effect of ethnic identity because they have had less experience coping with the consequences of discrimination.

The Current Study

Although experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination have been found to be prevalent among Asians living in the United States (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Gee, 2002; Goto, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2002; Rumbaut, 1994), the research on the psychological ramifications of these experiences remains scarce. Using the first-ever nationally representative sample of Asian adults in the United States, we can examine systematically how ethnic identity influences the association between discrimination and distress across age and nativity status. This goal is achieved in three steps. First, the current study examines differences in reports of discrimination and ethnic identity by age and nativity. Second, we examine the association between discrimination and mental health while taking into account respondents' age and nativity. It is expected that across the sample, discrimination will be associated with increased distress; however, for older individuals there may be an even stronger association between discrimination and outcomes due to the accumulation of life events over time. Further, it is hypothesized that individuals born in the United States will exhibit a weaker association between discrimination and health because being raised in the United States has likely included experiences that prepared them for experiences of discrimination. Third, in order to examine the role of ethnic identity in the association between discrimination and psychological outcomes, we will explore evidence for the buffering and centrality hypotheses while stratifying the sample by age and nativity. It is expected that during developmental periods when one's life is relatively stable, such as in midlife, centrality may be a buffer for discrimination. In contrast, at the youngest and oldest ages of our sample, when one's life circumstances are more likely to be changing, centrality may be more likely to exacerbate discrimination.

Method

Sample

The data come from the Asian respondents in the National Latino and Asian American Study, a household survey conducted between 2002 and 2003. In order to obtain a nationally representative sample, sampling strategies included three components. First, core sampling of primary sampling units (metropolitan statistical areas and counties) and secondary sampling units (from continuous groupings of Census blocks) were selected using probability proportion to size, from which housing units and household numbers were sampled. Next, high density supplemental sampling of census-block groups with greater than 5% density of target ethnic groups was included. Finally, second respondent sampling to recruit participants from households from which a primary respondent had already been interviewed was employed. Weights were developed to account for the joint probabilities of selection for these three components of the sampling design, allowing the sample estimates to be nationally representative. Specifically, the post-stratification weights adjust for the age and gender distribution of Asians living in the United States to match the Census.

Respondents were Asian adults ranging from 18 to 95 years of age and residing in the United States (N = 2,095). In order to create age groupings that were consistent with other life span research (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998), the current study examines only participants 18 to 75 years of age (N = 2,047; Table 1). The sample includes 586 Chinese, 491 Filipino, 508 Vietnamese, and 462 others (140 South Asians, 105 Japanese, 81 Koreans, 39 Pacific Islanders, and 97 others). Approximately 43% of the sample reported graduating from high school, and another 42% completed college or had an advanced degree, and the remaining 15% reported not completing high school. The majority of the sample (64%) was employed, but 18% reported living in poverty.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

| Characteristic | Unweighted (SE) | Weighted (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Female, % | 47.48 (1.10) | 47.56 (1.24) |

| Age, in years, mean | 40.30 (0.30) | 40.11 (0.73) |

| Ages 18–30, mean, % | 24.63 (0.16), 28.09 (0.99) | 24.40 (0.29), 30.02 (1.75) |

| Ages 31–40, mean, % | 35.30 (0.13), 25.21 (0.96) | 35.25 (0.13), 24.38 (1.27) |

| Ages 41–50, mean, % | 45.36 (0.13), 23.25 (0.93) | 45.24 (0.15), 21.90 (1.38) |

| Ages 51–75, mean, % | 59.42 (0.31), 23.45 (0.94) | 60.30 (0.58), 23.69 (2.22) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Vietnamese, % | 24.81 (0.96) | 12.96 (2.10) |

| Filipino, % | 23.99 (0.94) | 21.19 (2.25) |

| Chinese, % | 28.63 (1.00) | 28.58 (2.69) |

| Other, % | 22.57 (0.92) | 37.27 (2.45) |

| Imigration status | ||

| Born in U.S., % | 21.83 (0.92) | 23.20 (3.26) |

| Born outside U.S., % | 78.16 (0.91) | 76.70 (3.26) |

| Age of immigration, mean | 20.41 (0.35) | 19.59 (1.05) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast, % | 7.38 (0.58) | 15.88 (4.38) |

| Midwest, % | 4.44 (0.46) | 9.18 (2.28) |

| West, % | 6.84 (0.56) | 7.73 (2.28) |

| South, % | 81.33 (0.86) | 67.21 (4.36) |

| Key variables | ||

| Discrimination, mean | 1.71 (0.02) | 1.73 (0.02) |

| Ethnic identity, mean | 3.45 (0.02) | 3.38 (0.03) |

| Distress, mean | 13.16 (0.10) | 13.23 (0.13) |

| Family cohesion, mean | 3.68 (0.01) | 3.67 (0.02) |

| Social desirability, mean | 2.21 (0.04) | 2.23 (0.08) |

Procedures

Interviews were conducted using computer-assisted software and administered by trained interviewers with linguistic and cultural backgrounds similar to those of the respondents. Interviews were conducted in the respondent's choice of English, Cantonese, Mandarin, Tagalog, or Vietnamese. All instruments were translated using the standard techniques of translation and back-translation. The median length of the interview was 2.4 hr. As a measure of quality control, a random sample of participants with completed interviews was recontacted to validate the data. The overall response rate was 66%. Participants were compensated for their participation. Missing data for the variables reported here varied between .05 and .08%.

Measures

Psychological Distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) measured distress (Furukawa, Kessler, Slade, & Andrews, 2003). This 10-item inventory assesses the prevalence of negative feelings in the past 30 days (e.g., “how often did ….you feel depressed?, …hopeless?”). Respondents reported frequency on a 5-point scale (1 = none of the time, 2 = a little of the time, 3 = some of the time, 4 = most of the time, and 5 = all of the time) and responses were summed (range = 10 to 44; α = .83; Table 1). Because this variable was positively skewed, skewness = 2.37 (.05), kurtosis = 7.10 (.11), it was log transformed (range = .00 to .63, M = .09, SD = .10).

Perceptions of Racial and Ethnic Discrimination

Three items were averaged to assess the frequency of discrimination: “How often do people dislike you because you are (self-described ethnic/racial group)?,” “How often do people treat you unfairly because you are…?,” and “How often have you seen friends treated unfairly because they are…?” (Vega, Zimmerman, Gil, Warheit, & Apospori, 1993) on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often; α = .83; Table 1).

Ethnic Identity

A single item, “How close do you feel, in your ideas and feelings about things, to other people of the same racial and ethnic descent?,” measured ethnic identity centrality. Respondents indicated their agreement on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = not very close, 3 = somewhat close, and 4 = very close; Table 1).

Age

Consistent with life span research involving national samples (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998), age was categorized into four groups by decades: below 30 years old (n = 575), 31 to 40 years old (n = 516), 41 to 50 years old (n = 476) and 51 to 75 years old (n = 490). These groups approximate age groupings described as “young adults,” “adults,” “middle-aged adults,” and “older adults” (Diehl, Coyle, & Labouvie-Vief, 1996).

Nativity

Nativity was measured with a single item indicating whether the respondent was foreign born or U.S. born.

Demographic and Control Variables

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status has been observed to be related to reports of discrimination and distress (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999) and thus, an important covariate. Household income was derived from seven questions tapping sources of income (respondent, spouse, social security, government, family, and other), which were summed. Income was categorized by quartile, 1 = $0–10,999 (25.9%), 2 = $11,000–39,999 (27.2%), 3 = $40,000–74,999 (22.3%), 4 = $75,000+ (24.5%).

Age of immigration

Age of immigration has been found to be predictive of the prevalence of mental disorders (Takeuchi, Hong, Gile, & Alegria, 2007). As such, “How old were you when you first came to this country?” was included as a control for analyses conducted with individuals born outside of the United States (range = 0–70 years old).

Gender

Studies suggest that men often report more racial discrimination than women, although women often report more mental health problems than men (Kuo, 1995). Gender was included as a control variable (0 = male; 1 = female; Table 1).

Ethnicity

Asian ethnic groups in the United States vary in reports of discrimination (Gee et al., 2007; Kuo, 1995). Each of the four ethnic groups (i.e., Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and other) was dummy coded.

Region

Experiences of discrimination (Gee, 2002), ethnic identity (Umana-Taylor & Shin, 2007), and psychological well-being (Markus, Plaut, & Lachman, 2004) vary according to geographic location. Four regions were included as a control variable, Northeast (n = 152), Midwest (n = 91), West (n = 1707), and South (n = 145).

Family cohesion

Research among Asians in North America finds that support from family and same-ethnicity others buffers the effects of discrimination (Noh & Kaspar, 2003). To control for this influence, a 10-item scale assessing respondents' perception of family closeness was included (Olson, 1986). Respondents rated their agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, and 4 = strongly agree) with items such as “Family members feel very close to each other” and a mean was estimated (α = .93).

Social desirability

Because social desirability has been associated with lower reports of discrimination and mental disorders (Gee et al., 2007; Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005), a 10-item measure was included (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960; Paulhus, 1991). Respondents indicated whether statements such as “I have never met a person that I didn't like” were true (1) or false (0) and responses were summed (α = .71).

Results

The bivariate unweighted correlations between discrimination, ethnic identity, distress, family cohesion, and social desirability were estimated using SPSS (Table 2). There was a significant correlation between all of the variables with the exception of discrimination and ethnic identity. Discrimination was positively correlated with distress, such that more reports of discrimination were associated with more distress. Ethnic identity was found to have a negative correlation with distress, stronger ethnic identity being associated with less distress.

Table 2.

Correlation among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Racial/ethnic discrimination | — | −.02 | .17** | −.11** | −.07** |

| 2. Ethnic identity | — | −.08** | .23** | .07** | |

| 3. Distress | — | −.26** | −.08** | ||

| 4. Family cohesion | — | .15** | |||

| 5. Social desirability | — |

Note.

p < .01.

For the remaining analyses, the statistical software, Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, 2005), was employed to adjust for complex survey design weights. The weighted and unweighted means are shown in Table 1. Before proceeding with the primary analyses, differences in distress, discrimination, and ethnic identity by age and nativity were examined. Analyses of variance were conducted and found no differences in reports of distress by age group or nativity status (Table 3). The omnibus test for age differences in discrimination was significant with post hoc contrasts indicating that individuals 41 to 50 years of age reported significantly more discrimination than individuals over 51 years of age. Nativity was also associated with discrimination, such that individuals born internationally reported more discrimination than those born in the United States. As well, there were differences in reports of ethnic identity and family cohesion by age and nativity status. Post hoc contrasts revealed that individuals below 30 years of age reported significantly lower ethnic identity and family cohesion than the other three groups. In addition, individuals born outside the United States reported significantly stronger ethnic centrality and family cohesion than their United States–born counterparts. There were also age differences in reports of social desirability, the youngest age group reporting significantly lower levels than individuals over age 41. Immigrants scored higher on social desirability than U.S.-born individuals.

Table 3.

Comparison of Means Across Age Groups and Nativity Status (Weighted)

| Age, in years |

Nativity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 18–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–75 | F | Contrasts | Immigrant | U.S.-born | t |

| Distress | 13.35 | 13.38 | 13.28 | 12.88 | .57 | 13.31 | 13.03 | −.99 | |

| Discrimination | 1.72 | 1.76 | 1.81 | 1.64 | 3.77** | 41–50 > 51–75 | 1.76 | 1.60 | −5.07*** |

| Ethnic identity | 3.25 | 3.40 | 3.45 | 3.46 | 8.06*** | 18–30 < else | 3.45 | 3.14 | −5.37*** |

| Family cohesion | 3.58 | 3.70 | 3.69 | 3.76 | 15.35*** | 18–30 < else | 3.71 | 3.56 | −5.34*** |

| Social desirability | 1.80 | 2.18 | 2.37 | 2.72 | 26.81*** | 18–30 < 41–50, 51–75 |

2.44 | 1.69 | −5.96*** |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Analyses of variance were also conducted to examine the means for key variables, taking both nativity and age into account. Among individuals born overseas (Table 4), there was a significant difference in reports of discrimination by age, such that individuals 41 to 50 years of age reported significantly more than individuals over age 51. Differences in ethnic identity were also observed, those below age 30 reporting weaker identification than the two older age groups. Family cohesion also differed by age, such that the youngest group reported significantly lower cohesion compared to the other three age groups. Finally, there were also significant differences in reports of social desirability, the two younger groups reporting lower levels than the older two groups. Among United States–born individuals (Table 5), there was a significant difference in distress by age group, such that individuals 41 to 50 years of age reported less distress than individuals over 51 years of age. No differences were reported for discrimination, ethnic identity, or family cohesion; however, the oldest age group reported significantly higher levels of social desirability than the other three age groups.

Table 4.

Means by Age for Immigrants (Weighted)

| Age, in years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 18–30 (n = 373) |

31–40 (n = 425) |

41–50 (n = 407) |

51–75 (n = 395) |

F | Contrasts | All Ages (n = 1,600) |

| Distress | 13.34 (0.26) |

13.53 (0.41) |

13.19 (0.33) |

13.03 (0.24) |

.26 | 13.31 (.13) |

|

| Discrimination | 1.76 (0.07) |

1.80 (0.05) |

1.82 (0.05) |

1.68 (0.06) |

3.36* | 41–50 > 51–75 | 1.75 (0.02) |

| Ethnic Identity | 3.33 (0.08) |

3.45 (0.04) |

3.51 (0.03) |

3.51 (0.05) |

4.07** | 18–30 < 41–50, 51–75 | 3.45 (0.03) |

| Family Cohesion | 3.61 (0.04) |

3.72 (0.04) |

3.72 (0.02) |

3.78 (0.03) |

9.07*** | 18–30 < else | 3.71 (0.02) |

| Social desirability | 1.94 (0.19) |

2.35 (0.13) |

2.54 (0.20) |

2.81 (0.17) |

20.56*** | 18–30, 31–40 < 41–50, 51–75 |

2.43 (0.09) |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Means by Age for U.S.-Born Individuals (Weighted)

| Age, in years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 18–30 (n = 202) |

31–40 (n = 91) |

41–50 (n = 69) |

51–75 (n = 85) |

F | Contrasts | All Ages (n = 447) |

| Distress | 13.37 (0.40) |

12.69 (0.56) |

13.74 (0.64) |

12.29 (0.37) |

2.67* | 41–50 > 51–75 | 13.03 (0.27) |

| Discrimination | 1.63 (0.04) |

1.58 (0.06) |

1.71 (0.08) |

1.48 (0.05) |

1.21 | 1.60 (0.03) |

|

| Ethnic identity | 3.08 (0.11) |

3.18 (0.07) |

3.13 (0.09) |

3.26 (0.08) |

.54 | 3.14 (0.05) |

|

| Family cohesion | 3.51 (0.05) |

3.60 (0.05) |

3.52 (0.05) |

3.68 (0.04) |

1.85 | 3.56 (0.04) |

|

| Social desirability | 1.52 (0.15) |

1.41 (0.16) |

1.51 (0.15) |

2.37 (0.27) |

7.80*** | 51–75>else | 1.69 (0.09) |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Because age and nativity are seen to represent different developmental contexts, regression analyses were first conducted examining the effect of nativity status separately. Next, regression analyses were stratified by both variables (4 age groups × 2 immigration statuses = 8 analyses). With psychological distress as the outcome, the main effects of discrimination and ethnic identity as well as their interaction were included as predictors. In addition, socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, region, family cohesion, and social desirability were included. Age of immigration was included for analyses involving immigrant individuals. Before examining the effects of nativity status, the association between discrimination and ethnic identity and their interaction was estimated in the full sample. There was a main effect of discrimination on distress, such that more frequent reports of discrimination were associated with increased distress (b = .02, SE = .01, p < .01).

Examining just the subsample of immigrants, similar results were observed, such that more frequent reports of discrimination were associated with increased reports of psychological distress (Table 6, Column 1). To explore differences by age group, four regressions were conducted among the immigrant subsample (Table 7). Although the coefficients for the main effect of discrimination differ slightly across the age groups, the four models were found to be statistically equivalent, suggesting no differences between the groups (Chow, 1960). Moreover, ethnic identity did not moderate the effects of discrimination and distress in any of the four age groups.

Table 6.

Regressions of Distress by Nativity Status (Weighted)

| Immigrant |

U.S.-born |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI |

| Constant | .26** | .03 | .20, .32 | .28** | .06 | .16, .40 |

| Racial/ethnic discrimination | .02** | .01 | .01, .03 | .02† | .01 | .00, .04 |

| Ethnic identity | .00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | .00 | .01 | −.02, .01 |

| Ethnic identity × discrimination | .00 | .01 | −.02, .01 | .01 | .01 | −.02, .04 |

| Family cohesion | −.05* | .01 | −.06, −.03 | −.06*** | .01 | −.09, −.04 |

| Social desirability | .00 | .00 | −.01, .00 | .00 | .00 | −.01, .00 |

| R2 | .10 | .20 | ||||

Note. All regressions controlled for socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, region, and age of immigration (for immigrants only). A Chow test revealed no significant difference between these two models.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 7.

Regressions of Distress by Age, in Years, for Immigrants (Weighted)

| Ages 18–30 |

Ages 31–40 |

Ages 41–50 |

Ages 51–75 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI |

| Constant | .20** | .05 | .10, .30 | .38** | .09 | .19, .58 | .20** | .07 | .05, .33 | .25** | .07 | .10, .40 |

| Racial/ethnic discrimination | .03** | .01 | .01, .05 | .02* | .01 | .00, .04 | .01 | .01 | −.01, .03 | .02* | .01 | .00, .04 |

| Ethnic identity | .00 | .01 | −.01, .02 | .00 | .01 | −.02, .02 | .01 | .01 | −.01, .02 | .00 | .01 | −.02, .01 |

| Ethnic identity × discrimination | −.01 | .01 | −.03, .01 | .00 | .01 | −.03, .03 | .00 | .01 | −.01, .02 | .01 | .02 | −.02, .04 |

| Family cohesion | −.03* | .01 | −.05, .00 | −.08** | .02 | −.12, −.04 | −.05** | .02 | −.08, −.02 | −.03 | .02 | −.07, .01 |

| Social desirability | −.01 | .00 | −.01, .00 | .00 | .00 | −.01, .00 | .00 | .00 | −.01, .00 | −.01* | .00 | −.01, .00 |

| R2 | .15 | .15 | .14 | .10 | ||||||||

Note. All regressions controlled for socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, region, and age of immigration. A Chow test revealed no significant difference between these four models.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

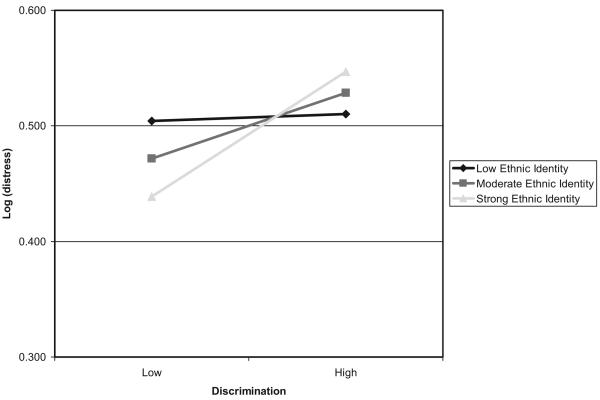

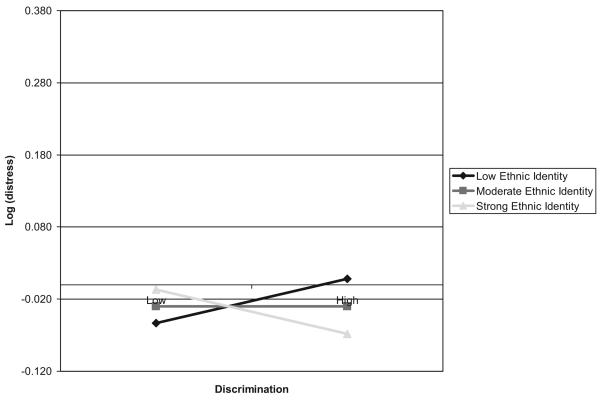

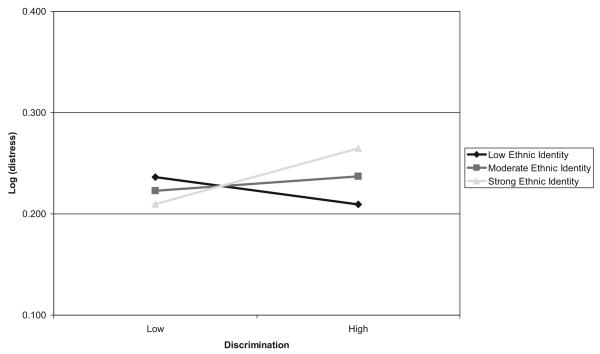

To examine possible age differences among individuals born in the United States, another four regressions were conducted (Table 8). For individuals below 30 years of age, only a main effect of discrimination was observed, such that increased discrimination was associated with increased distress. For individuals between 31 and 40 years of age, a main effect of discrimination as well as an interaction of discrimination and identity were observed. To explore the nature of this interaction, tests of simple effects were conducted (Aiken & West, 1991). Consistent with the centrality hypothesis, individuals with strong (1 SD above the mean) and moderate levels of centrality reported a significant positive association between discrimination and distress (b = .05, SE = .02, p < .05) and the slopes were significantly different from the low centrality group (Figure 1). For individuals between 41 and 50 years of age, there was also an interaction between discrimination and identity; however this interaction was consistent with the buffering hypothesis (Figure 2). Specifically, individuals with strong ethnic identity reported lower distress when faced with discrimination, whereas individuals with weaker ethnic identity reported the opposite pattern. Tests of simple slopes found that the high and low centrality groups differed from one another (b = −.06, SE = .03, p < .05). Finally, consistent with the centrality hypothesis, a significant interaction was also observed for those over 51 years of age (Figure 3). The slopes for the groups were significantly different (b = .04, SE = .02, p < .05), and individuals with high centrality reported more distress when they reported discrimination compared to those with low centrality.

Table 8.

Regressions of Distress by Age, in Years, for U.S.-Born Individuals (Weighted)

| Ages 18–30 |

Ages 31–40 |

Ages 41–50 |

Ages 51–75 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI |

| Constant | .33** | .07 | .20, .47 | .50** | .13 | .23, .77 | −.03 | .12 | −.28, .21 | .23*** | .06 | .09, .36 |

| Racial/ethnic discrimination | .03* | .01 | .01, .06 | .04* | .01 | .01, .07 | .00 | .02 | −.05, .05 | .01 | .02 | −.02, .05 |

| Ethnic identity | 0 | .01 | −.01, .02 | −.01 | .01 | −.02, .01 | −.01 | .03 | −.05, .02 | .01† | .01 | .00, .03 |

| Ethnic identity × discrimination | .01 | .01 | −.02, .03 | .05* | .02 | .01, .10 | −.06* | .03 | −.12, −.01 | .04* | .02 | .01, .07 |

| Family cohesion | −.07** | .02 | −.11, −.03 | −.09** | .03 | −.14, −.03 | −.02 | .01 | −.05, .01 | −.06*** | .02 | −.09, −.03 |

| Social desirability | .00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | −.01* | .01 | −.03, .00 | .00 | .01 | −.02, .01 | .00 | .00 | −.01, .01 |

| R2 | .31 | .43 | .32 | .37 | ||||||||

Note. All regressions controlled for socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, and region. A Chow test revealed no significant difference between these four models.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

U.S.-born 31- to 40-year-olds: The moderating effects of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and distress.

Figure 2.

U.S.-born 41- to 50-year-olds: The moderating effects of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and distress.

Figure 3.

U.S.-born 51- to 75-year-olds: The moderating effects of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and distress.

In sum, we find that discrimination was associated with increased distress for the entire sample. Moreover, among individuals born in the United States, the effect of discrimination varied by age and ethnic identity. Specifically, among individuals in their 30s and over 51, consistent with the centrality hypothesis, discrimination was exacerbated by ethnic identity. However, for individuals in their 40s, the effects of discrimination were buffered by ethnic identity.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to examine whether the effects of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and distress among Asian adults in the United States differed across developmental contexts defined by age and nativity status. We addressed this goal in three steps. As the first step, we examined differences in discrimination and ethnic identity by age and nativity status. First, we observed that immigrants reported a higher level of ethnic identity than non-immigrants. This finding is consistent with research that finds that immigrant individuals are more likely to describe their ethnicity using a national label (Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005; Rumbaut, 1994). Examining differences by age, we also observed significant differences in discrimination and ethnic identity. In particular, in line with life span developmental theories (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 2002), ethnic identity was weakest among the youngest age group (i.e., below 30 years of age). In addition, reports of discrimination appeared to decline with age, especially after age 51. A possible explanation might be found in how individuals are treated as they age. Specifically, individuals may gain more respect as they age and/or move into positions with more authority at work (Mroczek, 2004). If so, then they might be expected to experience less racial discrimination (although this does not preclude experiencing more age discrimination, which we did not measure). In addition, individuals growing up in a pre–Civil Rights era might interpret discrimination differently than younger individuals. The cross-sectional data precludes the investigation of true age, cohort, and period effects; but an indirect examination of cohort differences can be seen by comparing immigrant and nonimmigrant respondents. Although United States–born respondents as a whole did perceive less discrimination than immigrants, the age pattern was found in both groups, suggesting there may be more of an age effect than a cohort effect.

The Association Between Discrimination and Distress: Differences by Age and Nativity

Turning to the second goal of the study, we observed a significant main effect between discrimination and distress for the entire sample. This finding is consistent with existing literature on the effects of discrimination on mental health among Asian adults in the United States (Gee et al., 2007; Noh & Kaspar, 2003) and with the larger literature on the health effects of discrimination on minorities in general (e.g., Williams et al., 2003; Williams et al., 1999). Research on stress and coping finds that discrimination is an additional stressor with which individuals must contend, thereby affecting mental health (Clark et al., 1999; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Examining differences between immigrants and United States–born individuals, we did not find differences in the effects of discrimination by nativity status. As such, this study contributes to the growing body of research that finds that discrimination influences mental health for adults living in diverse developmental contexts defined by age, geography, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and immigrant status (Gee, 2002; Williams et al., 2003).

Ethnic Identity: Buffer or Exacerbator of the Association Between Discrimination and Distress?

The last step towards the study's goals involved examining the possible buffering or exacerbating role of ethnic identity in the association between discrimination and distress. Interestingly, among the immigrant subsample, despite reporting stronger ethnic identity than individuals born in the United States, ethnic identity centrality did not moderate the association between discrimination and distress. For individuals born in the United States, however, we observed support for both the centrality and buffering hypotheses. Among individuals 30 years of age and below, only a main effect of discrimination was observed, such that more reports of discrimination was associated with more distress. Although we had expected that that centrality might exacerbate discrimination at this age, there was no such moderation. According to developmental identity theories, younger individuals are still in the process of discovering and exploring their ethnic identity (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001; Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 2002). As such, one would expect heterogeneity of identity development within this age group to mask potential effects. Indeed, in this age group there is evidence for both the buffering and exacerbating effects of ethnic identity (e.g., Sellers & Shelton, 2003).

However, it is often argued that identity becomes more stable as individuals age (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001; Marcia, 2002; Phinney, 1990). By 31 years of age, in support of the centrality hypothesis, the association of discrimination with distress was stronger for those with a strong ethnic identity. More recent conceptualizations of ethnic identity development across the lifespan allow for patterns of recycling, whereby an event or encounter triggers a new search for the meaning and relevance of one's ethnic identity (Cross, 1991; Parham, 1989). Recent research suggests that ethnic and racial identity development may not be unidirectional (Yip et al., 2006). Instead, although one may have undergone an identity search during adolescence, an event in later adulthood (e.g., marriage) may prompt a new identity search (Cross, 1991; Parham, 1989). Such events are particularly likely to occur between the ages of 31 and 40 years. Therefore, discrimination based on one's ethnicity during this period of identity search may be especially detrimental.

For individuals between 41 and 50 years of age, there was support for the buffering hypothesis, such that individuals with strong ethnic identity were less likely to report distress when they reported discrimination. It has been suggested that the development of ethnic identity includes a repertoire of mechanisms for coping with discrimination (Cross, 1991; Phinney, 1990; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). Indeed, research that finds a direct relationship between ethnic identity and positive psychological adjustment suggests that this may be the case (Phinney, Cantu, & Kurtz, 1997; Phinney & Chavira, 1992). This may be particularly true for individuals 41 to 50 years of age because life span research on psychological well-being and age has found that as individuals enter middle age, they cope more effectively with stress and are better able to regulate emotional reactions to negative events (Cartensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Labouvie-Vief, Hakim-Larson, DeVoe, & Schoeberlein, 1989). Therefore, centrality might be protective during this age because one might have greater stability in their lives and more developed coping mechanisms that do not conflict with one's established ethnic identity centrality.

Although one would expect the buffering effect of identity on discrimination to persist after age 50, the pattern of exacerbation found around age 31 reappears. One possible explanation for this reversal comes from life span research on emotional well-being, which posits that as individuals begin to realize that they are aging, they restructure their goals and priorities to maximize happiness and minimize unhappiness (Cartensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000). As such, if individuals in this developmental period are actively trying to minimize negative interactions, being the target of discrimination may be especially noxious; particularly if discrimination is based on a central aspect of their identity. In fact, older adults report a stronger negative association between daily stress and negative affect (Mroczek & Almeida, 2004). Yet another explanation for the observed pattern is that although “midlife crises” have been believed to occur among individuals in their 40s, recent research suggests that such crises can also occur after age 50 (Wethington, Kessler, & Pixley, 2004). As such, experiences of discrimination during such a period of crisis may be especially noxious, resulting in the observed exacerbating pattern.

Taken together, age seems especially important for understanding whether ethnic identity buffers or exacerbates the effects of discrimination on distress among individuals born in the United States. Among 31- to 40- and 51- to 75-year-olds, we observe support for the centrality hypothesis; however, among 41- to 50-year-olds, buffering patterns are more apparent. Hence, the effects of ethnic identity do not conform to a uniform pattern across the life span. Interestingly, there were no differences across the age groups in mean level of ethnic identity for individuals born in the United States. This suggests that the differences in centrality versus buffering that we observe may be tapping into different functions that ethnic identity may have over the life course. That is, although levels of ethnic identity do not seem to vary across age groups, but its role with respect to mental health might.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current study helps reconcile the literature on the equivocal effects of ethnic identity on the association between discrimination and distress. Specifically, by observing support for both the centrality and buffering hypotheses (depending upon an individual's nativity status and age), this study contributes to our knowledge of the interconnection between ethnic identity, discrimination, and mental health. Even so, there are limitations to the current study. First, due to resource constraints related to conducting a national study, this study used a single indicator of ethnic identity. Studies employing multidimensional measures of ethnic identity find that different dimensions of ethnic identity serve unique roles (Lee, 2005; Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Yip, 2005; Yip & Fuligni, 2002). Therefore, the current study cannot provide information about how the structure and meaning of ethnic identity may differ across the immigrant and nonimmigrant groups.

Second, the data are cross sectional. Future longitudinal data can more directly examine how patterns of discrimination and identity and their potential associations with distress change over time. Relatedly, cross-sectional data do not allow teasing apart developmental and cohort effects (Charles, Reynolds, & Gatz, 2001). For example, the United States saw a surge of Asian immigrants post-1965 (Takaki, 1998); these individuals are most likely represented in the subsample of immigrants over 51 years old and their offspring in the subsample of 31- to 40-year-olds born in the United States. Therefore, it is not clear whether the patterns observed in these two groups reflect developmental phenomenon or whether there is something unique about the cohort of individuals who came to the United States during this period.

It is noteworthy that the variance in distress accounted for by discrimination and identity differed considerably between the immigrants and nonimmigrants, with more variance explained in the United States–born subsample. It is possible that our measure of identity centrality is more relevant to the U.S. born, among whom the racial and ethnic hierarchies are more salient. This greater relevance might persist even though the immigrants reported higher levels of centrality because of measurement error. Indeed, we cannot rule out measurement error that might result in differences between nativity groups. For example, Asians who are more traditionally oriented might tend to underreport symptoms of distress (Takeuchi et al., 1998). Although controls for social desirability reduce this concern, future research that uses similar concepts of identity, discrimination, and distress, with high attention to local explanatory frameworks, should be conducted cross-nationally.

In conclusion, our study finds that discrimination is associated with distress, a finding echoed in many other studies (e.g., Bhui et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2003). Our use of the first-ever, nationally representative study of Asians in the United States helps buttress the findings of other studies employing student and other convenience samples. The current study extends the literature on the moderating effects of ethnic identity on discrimination by showing that this association varies by age and nativity status. Much work remains to more fully investigate how discrimination may influence psychological well-being and how interpersonal and contextual factors may moderate this association. A fuller understanding of these issues could help efforts to develop environmental and psychological resources that may protect against the effects of discrimination.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants MH06220, MH62207, and MH62209 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Robert Wood Johnson Grant DA18715, with generous support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, NIH, and Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, NIH. We would also like to acknowledge Seughye Hong and Anita Rocha for their friendly and prompt response to requests for data.

Contributor Information

Tiffany Yip, Department of Psychology, Fordham University.

Gilbert C. Gee, The School of Public Health, University of California Los Angeles

David T. Takeuchi, School of Social Work, University of Washington.

References

- Adams JP, Dressler WW. Perceptions of injustice in a Black community. Human Relations. 1988;41:753–767. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Horn MC. Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 425–450. [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: Findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic Minority Groups in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(3):496–501. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(1):135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-F, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartensen LL, Pasupathi P, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences in change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(1):136–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, Monin B. “Where Are You Really From?”: Asian Americans and Identity Denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(5):717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow G. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica. 1960;28(3):591–605. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr. Shades of black: Diversity in African-American identity. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr., Fhagen-Smith P. Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In: Jackson B, Wijeyesinghe C, editors. New perspectives on racial identity development: A theoretical and practical anthology. New York University Press; New York: 2001. pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Coyle N, Labouvie-Vief G. Age and sex differences in strategies of coping and defense across the lifespan. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:127–139. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Witkow M, Garcia C. Ethnic identity and academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(5):799–811. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and the K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(2):357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC. A mulitlevel analysis of the relationship between institutional racial discrimination and health status. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):615–623. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Yip T, Takeuchi DT. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(10):1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto SG, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(2):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Walters EE. Age and depression in the MIDUS study. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measure and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services. 1999;29(2):295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH. Coping with racial discrimination: The case of Asian Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1995;18(1):109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G, Hakim-Larson J, DeVoe M, Schoeberlein S. Emotions and self-regulation: A life span view. Human Development. 1989;32(5):279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A. Psychological stress and coping in aging. American Psychologist. 1983;38:245–254. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.38.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity and psychosocial development in adulthood. An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2002;2(1):7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Plaut VC, Lachman ME. Well-being in America: Core features and regional patterns. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being in mid-life. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 614–650. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SK, Major B. Group identification moderates emotional responses to perceived prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(8):1005–1017. doi: 10.1177/0146167203253466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK. Positive and negative affect at midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2004. pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Almeida DM. The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(2):355–378. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(5):1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E, Shelton JN, Sellers RM. The role of racial identity in managing daily racial hassles. In: Philogene G, editor. Race and identity: The legacy of Kenneth Clark. American Psychological Association Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH. Circumplex Model VII: Validation studies and FACES III. Family Processes. 1986;25:337–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Fiske ST. Ethnic identity moderates perceptions of prejudice: Judgments of personal versus group discrimination and subtle versus blatant bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(5):550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Parham TA. Cycles of psychological nigresence. The Counseling Psychologist. 1989;17:187–226. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D. Measurement and control of response bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver P, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Academic Press; San Diego: 1991. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescence and adulthood: A review and integration. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist. 1996;51(9):918–927. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Cantu CL, Kurtz DA. Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1997;26(2):165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Chavira V. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: An exploratory longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence. 1992;15(3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(92)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(3):271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith MA. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28(4):748–794. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado de Snyder VN. Factors associated with acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among married Mexican immigrant women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1987;11:475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(5):1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Sellers RM. Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26(1):27–50. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata statistical software (Version 9) StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Hogg M, Abrams D, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Psychology Press; New York: 2001. pp. 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Takaki R. Strangers from a different shore: A history of Asian Americans. Little, Brown and Company; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Chung RC-Y, Lin K-M, Shen H, Kurasaki K, Chun C-A, Sue S. Lifetime and twelve-month prevalence rates of major depressive episodes and dysthymia among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(10):1407–1414. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Gile K, Alegria M. Developmental contexts and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Research in Human Development. 2007;4(1):49–69. doi: 10.1080/15427600701480998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell; Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Shin N. An examination of ethnic identity and self-esteem with diverse populations: Exploring variation by ethnicity and geography. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(2):178–186. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents' mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(4):549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bamaca-Gomez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity. 2004;4(1):9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Zimmerman R, Gil A, Warheit G, Apospori E. Acculturation strain theory: Its application in explaining drug use behavior among Cuban and other Hispanic youth. In: De La Rosa M, Reico JL, editors. Drug abuse among minority youth. National Institute of Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1993. pp. 144–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Kessler RC, Pixley JE. Turning points in adulthood. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 585–613. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Spencer MS, Jackson JS. Race, stress, and physical health: The role of group identity. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity and Health. 2000;5(34):243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T. Sources of situational variation in ethnic identity and psychological well-being: a palm pilot study of Chinese American students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(12):1603–1616. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Fuligni AJ. Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological well-being among American adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1557–1572. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity context, and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1503–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]