Abstract

Investigating gas-phase structures of protein ions can lead to an improved understanding of intramolecular forces that play an important role in protein folding. Both hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange and ion mobility spectrometry provide insight into the structures and stabilities of different gas-phase conformers, but how best to relate the results from these two methods has been hotly debated. Here, high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) is combined with Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT/ICR MS) and is used to directly relate ubiquitin ion cross sections and H/D exchange extents. Multiple conformers can be identified using both methods. For the 9+ charge state of ubiquitin, two conformers (or unresolved populations of conformers) that have cross sections differing by 10% are resolved by FAIMS, but only one conformer is apparent using H/D exchange at short times. For the 12+ charge state, two conformers (or conformer populations) have cross sections differing by <1%, yet H/D exchange of these conformers differ significantly (6 versus 25 exchanges). These and other results show that ubiquitin ion collisional cross sections and H/D exchange distributions are not strongly correlated and that factors other than surface accessibility appear to play a significant role in determining rates and extents of H/D exchange. Conformers that are not resolved by one method could be resolved by the other, indicating that these two methods are highly complementary and that more conformations can be resolved with this combination of methods than by either method alone.

Understanding biomolecule conformation and folding is an important challenge in chemistry [1, 2]. In solution, many experimental methods for determining biomolecular conformation have been developed, including NMR, crystallography, and mass spectrometry based methods. Effects of solvent on molecular structure and folding are often inferred indirectly from experiments done with different solvent systems. In the gas phase, molecular conformation can be investigated using gas-phase H/D exchange [3–6], ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) [7–9], proton transfer reactivity [10, 10b, 10d], ion-surface imprinting [11], molecular dynamics simulations [12], ion energy loss measurement [13, 14], and dissociation experiments [15]. These experiments provide insight into the conformations of ions in the complete absence of solvent, and from such experiments, the effects of solvent on molecular structure can be directly determined.

Pioneering gas-phase H/D exchange experiments of McLafferty and coworkers clearly demonstrated that multiple conformations of proteins can exist in the gas phase [3]. For cytochrome c, a total of seven different gas-phase conformers were identified based on different extents of H/D exchange. Interestingly, several charge states formed directly by electrospray ionization had only one conformer whereas others were found to have multiple conformers with the 7+ charge state having all seven. In combination with charge stripping as well as IR heating with a CO2 laser, gas-phase proteins were found to both unfold as well as fold in the complete absence of solvent [3b]. Subsequent proton transfer reactivity and IMS experiments have also demonstrated gas-phase protein folding [2, 9d, 10a]. Implicit in the interpretation of the H/D exchange data is the assumption of a relationship between the extents of H/D exchange and surface accessibility, and its relation to the compactness of a conformer. However, some evidence has suggested surface accessibility may not be a dominant factor in H/D exchange extents for some peptides and proteins [2, 5, 16].

From ion mobility spectroscopy, it is possible to obtain collisional cross sections of gas-phase ions from which information about structure can be inferred. This method has been used extensively for obtaining detailed information on small ions and atomic clusters [17]. For proteins, multiple distinct gas-phase conformers have been observed [2, 7–9]. In general, cross sections increase with ion charge state. For example, cytochrome c charge states below 5+ have cross sections that are slightly lower than the cross section calculated for a native solution structure. The cross section of the 19+ approaches the calculated cross section for a fully extended conformer [9a]. For intermediate charge states, as many as five different conformers have been identified. Interestingly, the cross sections of the more open conformers increase with charge state whereas McLafferty and coworkers [3b] found that H/D exchange extents for the four most open conformers decrease with charge state. This result is consistent with increased local structure around charge sites for these conformers [3b]. Jarrold has shown that more compact protein conformers hydrate more readily and that gas-phase hydration can result in the folding of more open conformers [2].

A key difficulty in comparing results from H/D exchange to IMS results is that these two methods probe different physical properties of an ion. In addition, H/D exchange experiments and the ion mobility spectroscopy experiments typically measure ion conformation on two very different time frames. Ion mobility experiments probe ion conformation within ~10 ms of their formation, whereas H/D exchange experiments done in Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT/ICR) mass spectrometers typically probe ion conformation several seconds or even hours after ion formation. Clemmer and coworkers investigated the effects of storing ions for up to 30 s in an RF ion trap before their analysis by IMS [9a, b]. They observed that some compact conformer populations unfolded during this time frame whereas others did not. Valentine and Clemmer have also investigated H/D exchange in the drift tube of an ion mobility spectrometer [18]. They did not observe a charge state dependence to H/D exchange extents for a given conformer separated by IMS, but they did report that compact structures underwent less exchange than more open structures.

High-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS), a method based on principles first demonstrated by Buryakov et al. [19], has recently been applied to the separation of protein conformers [14, 20, 20a]. The separation is based on the dependence of ion mobility on the electric field strength. In FAIMS, ions pass between two cylindrical electrode surfaces across which an asymmetric RF potential waveform is applied, alternately exposing the ions to strong and weak electric fields. Different mobilities of the ions during the high field versus low field portion of the waveform result in the ions drifting towards one of the electrodes. This drift can be compensated for by using a D C potential. By varying this “compensation” voltage (CV), ions are separately transmitted through the FAIMS device into the mass spectrometer. This method has the advantage over the more widely used drift tube ion mobility spectroscopy experiments in that very high ion transmission is possible [21], and the method can be readily used with virtually any type of mass spectrometer. A current limitation is that it is not readily possible to obtain absolute cross sections from these experiments.

Purves et al. have used FAIMS to separate different conformers of bovine ubiquitin [14]. In combination with ion retarding potential measurements, it was possible to obtain ion cross sectional measurements as a function of CV values. The cross sections obtained using this method were larger than those reported by Clemmer and coworkers [9c, 10c] for these same ions. However, by normalizing their data to the 13+ charge state for which there was only one conformer identified using both techniques, Purves et al. [14] reported that the remaining cross sections closely matched the ion mobility data, with an average deviation of 1.5%. A few additional conformers were resolved using FAIMS [14].

Here, we report the combination of FAIMS with H/D exchange experiments done in FT/ICR MS to investigate the structure of ubiquitin ions. Ubiquitin ions were chosen because they have been investigated by energy loss measurements in combination with FAIMS, IMS, and H/D exchange. These experiments for the first time make possible a direct comparison between H/D exchange experiments in FT/ICR MS with collisional cross section measurements by IMS. We find that H/D exchange extents do not significantly correlate to collisional cross sections and that these methods for conformer separation appear to be highly complementary, with many conformers identified by one method, but not the other.

Experimental

FT/ICR Mass Spectrometer

The Berkeley-Bruker 9.4 tesla FT/ICR mass spectrometer is used for all experiments [22]. Ions are produced by electrospray ionization using a 0.1 mm i.d. stainless steel capillary connected to a syringe pump system to maintain a solution flow rate of 2 μL/min. This capillary was positioned 5 mm away from the ion entrance hole in the FAIMS device and a voltage of 2000 V was applied to the capillary. No nebulizing gas was used. Solutions were prepared from a 1 × 10−3 M stock solution of ubiquitin in water which was stored at −50 °C when not in use. A solution of 49.5/49.5/1% water/methanol/acetic acid with a bovine ubiquitin concentration of 10−5 M was used for electrospray ionization. The D2O and bovine ubiquitin used in these experiments were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) and were used as received. Methanol and acetic acid were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) and were used as received.

H/D exchange was performed by introducing D2O into the mass spectrometer through a piezoelectric valve attached to the ultrahigh vacuum chamber. This valve is controlled using the Xmass data acquisition software (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). This valve is opened for 10 to 60 s during which time the pressure is ~8 × 10−7 torr as measured on an uncalibrated ion gauge located ~1.5 m from the ion cell. After the valve is closed, a 120 s delay before ion detection is used to allow the system to pump down and reach a pressure of ~2 × 10−8 torr. The number of deuteriums incorporated is calculated from the mass difference between the center of the exchanged isotope distribution and the center of the isotope distribution with no H/D exchange. The extent of H/D exchange at a given exchange time was reproducible to under ±3 deuteriums incorporated. This variation in H/D exchange extents correlated to pressure changes in the D2O reservoir. After the experiments reported here, modifications to the gas inlet system improved H/D exchange reproducibility. No difference was detected between H/D exchange experiments with and without isolation of neighboring charge states. Therefore, no isolation in the ion cell was used in these experiments.

An extended pseudo-open cylindrical cell was built and used in these experiments. Improved resolution and ion storage during H/D exchange was obtained using this cell compared with the cell used previously [22]. The total length of the cell is 300 mm with an i.d. of 60 mm. This cell is similar to other open cylindrical cell designs [23] except that the excite/detect plates of the cell have been extended to 150 mm long relative to the 60 mm trapping cylinders. Thus, the length of the excite/detect plates is 2.5 times the length of the trapping cylinders. Capacitive coupling between the excite/detect plates and cylindrical trapping plates [24] has not yet been incorporated in this cell. The open cylindrical design was further modified by the inclusion of several additional trapping plates. These vertical plates allow ions to be trapped with similar experimental conditions as the previous cell. During ion injection, the potential on the trapping plates is 4 V. Nitrogen gas is pulsed into the mass spectrometer to assist in trapping the ions. The voltage on the trapping plates is then raised linearly to 6 V in 1.5 s for improved ion trapping during H/D exchange. The voltage on the trapping plates is then linearly lowered to 1 V in 1.5 s before excitation and detection.

FAIMS

The Ionalytics Selectra (Ionalytics, Ottawa, Canada) was used for all FAIMS experiments. The FAIMS device is interfaced with the mass spectrometer by using a PEEK sleeve to hold the FAIMS device in proper alignment with the mass spectrometer. An o-ring between the capillary entrance aperture of the mass spectrometer and the exit orifice in the FAIMS device makes possible a gas-tight interface between the two devices. A dispersion voltage (DV) of −3600 V and a nitrogen carrier gas flow rate of 2.5 L/min produced CV scans similar to those reported in reference [14]. Optimal performance of the FAIMS device is achieved at dispersion voltage DV values above −4400 V. However, these higher DV values significantly shift the CV required for ion transmission compared with the CV scans reported by Purves et al. [14]. The experimental conditions of our FAIMS device were chosen to yield CV scan peaks similar to those obtained by Purves et al. when measuring ubiquitin cross sections [14]. The CV is generated by using a spare power supply on the mass spectrometer and this voltage is controlled by the Bruker Xmass software. The acquisition of CV scans was facilitated by the use of a custom Xmass Tcl/Tk script. This script steps a user-selected Xmass variable by a specified increment and range, and saves a mass spectrum at each step. All Bruker Xmass mass spectra data files were processed using R statistical analysis software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [25].

Results and Discussion

H/D Exchange

To combine H/D exchange with FAIMS over a wide CV range, it is desirable to keep the H/D exchange times as short as possible to reduce the potentially lengthy time required for these experiments. To determine the extent to which different conformers can be resolved using short exchange times, H/D exchange was performed on the entire charge state distribution of ubiquitin using reaction times of 20 and 40 s. The results of these experiments are summarized in Table 1. For the 8+ through 10+ charge states, the extents of exchange increase roughly linearly with reaction time, and two conformers (or conformer populations) are clearly resolved. For the 7+ charge state, two very low abundance conformers are resolved at 20 s, but the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) is insufficient to observe these conformers at 40 s. For the 11+ and 12+ charge states, the extent of H/D exchange does not increase linearly with reaction time. Three 11+ conformers and two 12+ conformers are clearly resolved. The average difference in exchange is roughly constant at these two exchange times, although a third population appears at 40 s for the 11+ that is not apparent at 20 s. For the 13+ charge state, only one conformer is observed at the shorter reaction time, and no signal is observed at 40 s because of poor S/N for this ion. These results are in striking contrast to recent results of Geller and Lifshitz who resolved two different conformers for only the 13+ charge state using ND3 as an exchange reagent [6a].

Table 1.

H/D exchange extents and relative conformer abundance for the 7+ to 13+ charge states of ubiquitin measured after 20, 40, 3600 s of exchangea

| 20 s H/D exchange |

40 s H/D exchange |

3600 s H/D exchangeb |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin charge state |

Number of exchanges |

Relative intensity |

Distribution width (Da) |

Difference in exchange |

Number of exchanges |

Relative intensity |

Distribution width (Da) |

Difference in exchange |

Number of exchanges |

Relative intensity |

Distribution width (Da) |

Difference in exchange |

| 7+ | 21c | 0.42 | 31 | -- | 88 | 1 | 29 | |||||

| 7 | 1 | 17 | 14 | -- | 69 | 0.27 | 37 | 19 | ||||

| 8+ | 18 | 1 | 21 | 35 | 1 | 23 | 85 | 1 | 29 | |||

| 6 | 0.62 | 17 | 12 | 10 | 0.44 | 15 | 25 | 76 | 0.12 | 25 | 9 | |

| 9+ | 24 | 1 | 21 | 48 | 1 | 24 | 82 | 1 | 19 | |||

| -- | 25 | 0.13 | 14 | 23 | -- | |||||||

| 10+ | 21 | 0.43 | 21 | 42 | 0.39 | 21 | 85 | 1 | 23 | |||

| 7 | 1 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 1 | 21 | 25 | 63 | 0.09 | 21 | 22 | |

| 11+ | -- | 47 | 0.29 | 21 | 76 | 0.27 | 16 | |||||

| 21 | 1 | 19 | 31 | 1 | 19 | 16 | 60 | 1 | 21 | 16 | ||

| 6 | 0.19 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 0.3 | 14 | 31 | 47 | 0.07 | 13 | 29 | |

| 12+ | 17 | 0.18 | 14 | 25 | 0.12 | 14 | 50 | 1 | 23 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 19 | 27 | 0.9 | 19 | 23 | |

| 13+ | 0 | 1 | 10 | -- | 12 | 1 | 18 | |||||

20 and 40 s data obtained with a D2O pressure of ~8 × 10−7 torr.

H/D exchange extents and relative intensities obtained from data in reference [4].

The number of hydrogens exchanged for each conformer within a charge state is calculated from the mass difference between the centers of the H/D exchange isotope distribution and the isotope distribution with no H/D exchange.

Also included in Table 1 are the data obtained by Marshall and coworkers [4] who did H/D exchange on ubiquitin ions using D2O and 1 h reaction times. Overall, we find excellent agreement between the results of our H/D exchange done at relatively short times and those of Marshall who used 90- to 180-fold longer reaction times. Of the 144 exchangeable hydrogens in bovine ubiquitin, 6 t o 4 8 deuteriums for the various charge states are incorporated with 40 s o f H/D exchange versus the 27 to 88 hydrogens exchanged as reported by Marshall and coworkers. The number of conformers resolved in both experiments is the same for each charge state. The absolute differences in the numbers of exchanges between different conformers of the same charge state are in some cases larger at the significantly shorter reaction times used here. For example, the average difference in H/D exchange for the two conformers of the 8+ charge state is 12, 25, and 9 at 20, 40, and 3600 s. Similarly, a greater difference in absolute exchange is observed for 10+ charge state at 40 s than at 3600 s. Thus, higher separation efficiency or conformer resolving power is obtained at short H/D exchange times for the 8+ through 12+ charge states for bovine ubiquitin.

The abundances of the isomers observed in these experiments differed from those reported by Marshal and coworkers [4]. For all charge states where multiple conformers are observed (except for the 12+), the relative abundances of the different conformers are more similar in our experiments than those observed by Marshall and coworkers. For the 7+, 10+, and 12+ charge states, the lower exchanging population has the greater abundance at 20 s and 40 s, but a lower abundance at 3600 s. The different abundances for the various conformers observed in these two experiments are likely due to either different ion source/ion introduction conditions or to isomerization of the conformers during extended H/D exchange times.

The abundances of the isomers can be affected by the length of time ions are accumulated in the hexapole before ion introduction into the FT/ICR cell. Short times (~0.2 s) resulted in the maximum number of conformers observed. Clemmer and coworkers demonstrated a shift in ion abundances at different cross sections as ion storage time in an ion trap was increased [9a, b], a result consistent with collisional heating that can occur in RF storage devices.

These results indicate that there is no definitive trend in H/D exchange extents with charge states at short reaction times. The maximum extents of exchange are observed for intermediate charge states. In contrast, there appears to be a trend of decreasing H/D exchange extent with increasing charge state at the very long exchange time. The H/D exchange results from McLafferty and coworkers noted this trend of decreasing H/D exchange at the higher charge states for several other proteins as well [3]. Our results at short exchange times can be attributed to differences in the H/D exchange rates versus the maximum extents of exchange for these different charge states.

Cross Sections

To relate FAIMS CV values to cross section measurements, it is necessary to essentially “calibrate” FAIMS using another method that can be directly related to the highly accurate cross sections measured using ion mobility spectroscopy. Purves et al. combined FAIMS with energy retarding potential measurements in a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer [14]. Collisional cross sections were determined from measurements of the translational energy that ions lose through collisions with a buffer gas. These cross section values were ~20% greater than the corresponding cross sections measured by IMS. After normalizing the collisional cross sections measured by translational energy loss to those measured by IMS using the 13+ charge state as a reference point, the values closely matched, within 1.5% on average. These measurements make it possible to directly relate CV values to collisional cross sections for ubiquitin [9c, 14].

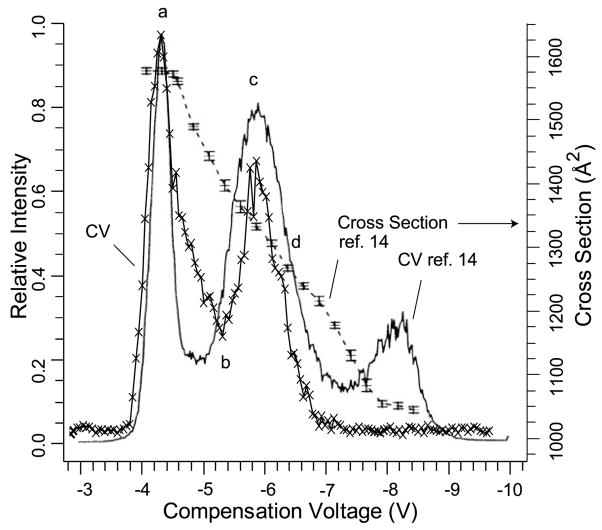

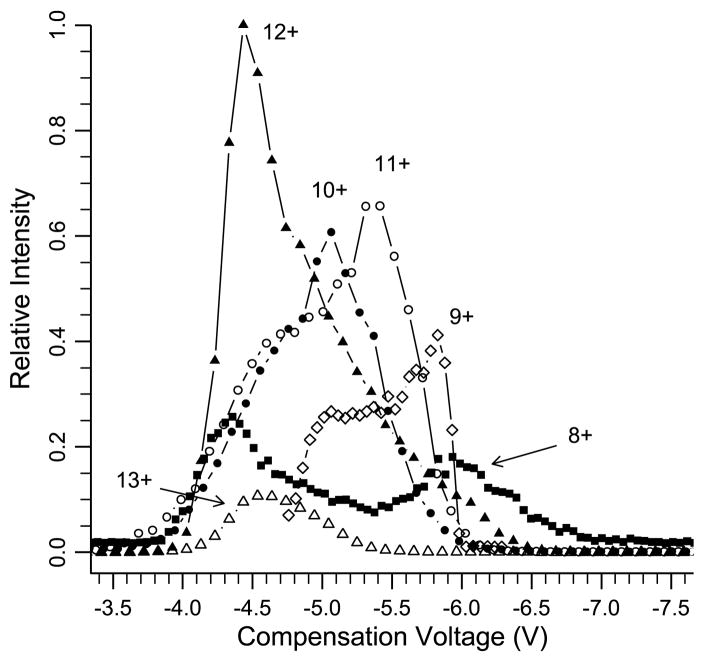

Experimental FAIMS conditions were adjusted to obtain CV scans similar to those obtained by Purves et al. [14] in which they combined FAIMS with energy loss collisional cross section measurements. Results of a CV scan for the 8+ charge state of ubiquitin under these conditions are shown in Figure 1. Also shown on this same plot is the CV scan for this same ion measured by Purves et al. [14], as well as their collisional cross section values measured as a function of CV. Our FAIMS CV scans indicate the presence of two clearly resolved conformers, or two families of unresolved conformers compared with three observed by Purves et al., a result that is likely related to slightly different electrospray conditions in the two experiments. The separation of the two peaks that are centered at the lowest CV values is nearly the same (±0.1 V) in both experiments. Similar matches are observed for the 9+ through 12+ charge states, with our CV scans for the 10+ and 12+ charge states indicating two unresolved conformers (Figure 2) versus three and two resolved conformers reported by Purves et al. for these respective ions. From these results, it is possible to relate CV values measured for various conformers of different charge states to the physical cross sections of these ions. For example, the two 8+ conformers that are transmitted at CV values of −4.4 and −6.0 V have cross sections of 1585 and 1330 Å2, respectively. By comparison, the crystal structure of ubiquitin has a cross section of 930 Å2 and a fully extended structure has a cross section of 2140 Å2 [9b, 10c].

Figure 1.

Comparison of a CV scan for the 8+ charge state of ubiquitin obtained with a FT/ICR mass spectrometer (line with letters x) with a scan obtained previously by Purves et al. (solid line) [14]. Collisional cross section measurements made by Purves et al. [14] for this charge state are indicated by the dashed line with error bars. Letters a to d indicate CV values for the H/D exchange mass spectra shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Compensation voltage scans for the 8+ to 13+ charge state of bovine ubiquitin.

FAIMS with H/D Exchange

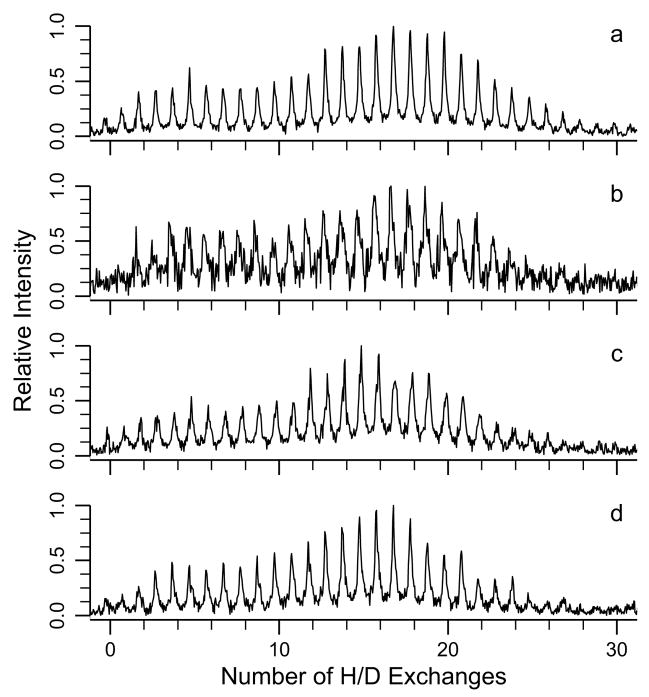

Experiments combining FAIMS with H/D exchange were done to determine how the extent of H/D exchange correlates with the collisional cross section of an ion. H/D exchange results (20 s) for the 8+ charge state measured at four different CV values are shown in Figure 3. The CV values of −4.4, −5.4, −6.0, and −6.4 V correspond to ion cross sections of 1585, 1410, 1330, and 1280 Å2, respectively. As can be seen from the H/D exchange data in Figure 3, two distinct conformers or families of unresolved conformers, centered around 6 and 18 incorporated deuteriums, are resolved using H/D exchange at each of these CV values (the slightly higher extent of exchange in Figure 3 a, b versus c, d is an artifact attributable to slightly higher pressures of gaseous D2O). There is no obvious change in the abundance of these two conformer families as measured by H/D exchange despite the significantly different physical cross sections of the ions at the different CV values. These results clearly demonstrate that the two conformer families that are resolved using FAIMS have essentially the same H/D exchange extents. Similarly, H/D exchange resolves two families of conformers that are not resolved using FAIMS. These results indicate that H/D exchange is sensitive to conformational differences between these ion populations that is not directly related to the collisional cross sections of these ions, or that the ion populations undergo isomerizations to two different conformations on the long time frame of the H/D exchange experiments.

Figure 3.

H/D exchange mass spectra for the 8+ charge state of ubiquitin with 20 s reaction time at ~8 × 10−7 torr at compensation voltages of (a) −4.4 V, (b) −5.3 V, (c) −5.9 V, and (d) −6.5 V corresponding to a 300 Å2 range of collisional cross sections.

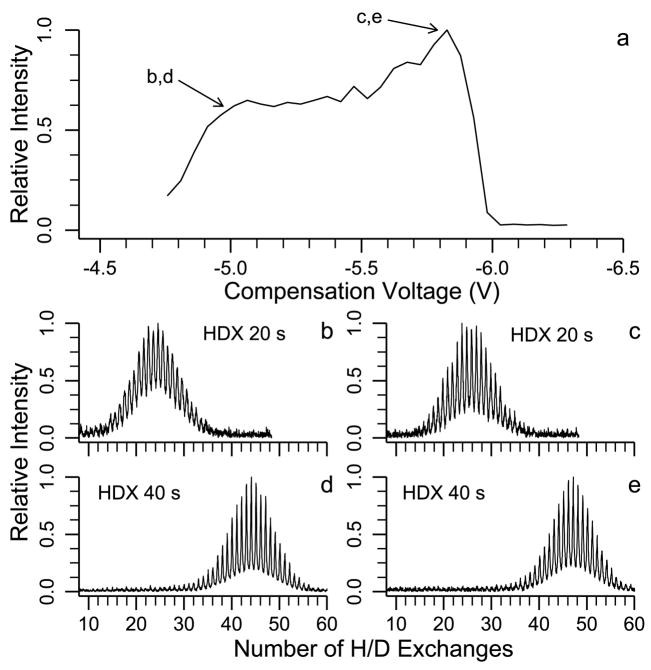

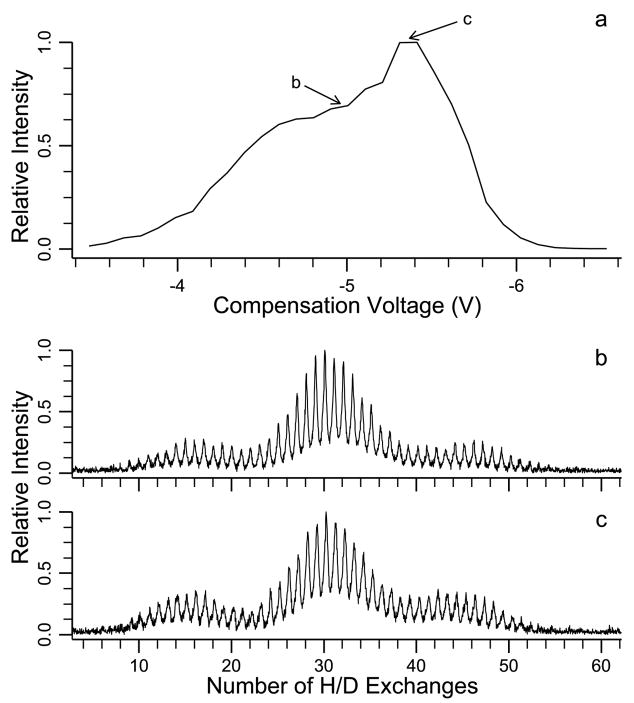

Results of the FAIMS-H/D exchange experiments for the 9+ charge state are shown for both 20 and 40 s reaction times in Figure 4. A broad peak in the CV scan is observed indicating the presence of two or more largely unresolved conformers (Figure 4a). Maxima in the CV data occur at −5.8 and −5.0 V. These values are within 0.1 V o f those for the two peaks observed by Purves et al. [14] who reported better resolved peaks with collisional cross sections for the constituent ions of 1460 and 1625 Å2, respectively. H/D exchange data measured at these two CV values are shown in Figure 4b–e. Both at 20 s and at 40 s, a single isotope distribution is observed corresponding to an average of 24 and 48 deuteriums incorporated, respectively. Prior H/D exchange experiments (Table 1) did resolve a second lower exchanging distribution at 40 s o f H/D exchange. Marshall and coworkers also reported a lower exchanging distribution for this charge state [4]. The low abundance of this distribution makes this conformation difficult to detect consistently. In contrast, the FAIMS results indicate that at least two conformers are initially present in similar abundance. This could be due to the presence of multiple conformers that are stable on the lifetime of the FAIMS measurements (hundreds of ms [26]), but which isomerize to a single conformer (or unresolved family of conformers) on a time frame much shorter than the H/D exchange reaction time (tens of s). Another possible explanation for this result is that the conformers that have different physical cross sections undergo the same extent and rate of H/D exchange.

Figure 4.

FAIMS-FT/ICR MS data for the 9+ charge state of ubiquitin: (a) CV scan and (b), (c), (d), (e) H/D exchange measured at CV values of −5.0 V (b), (d) and −5.8 V (c), (e) at 20 s (b), (c) and 40 s exchange time (d), (e).

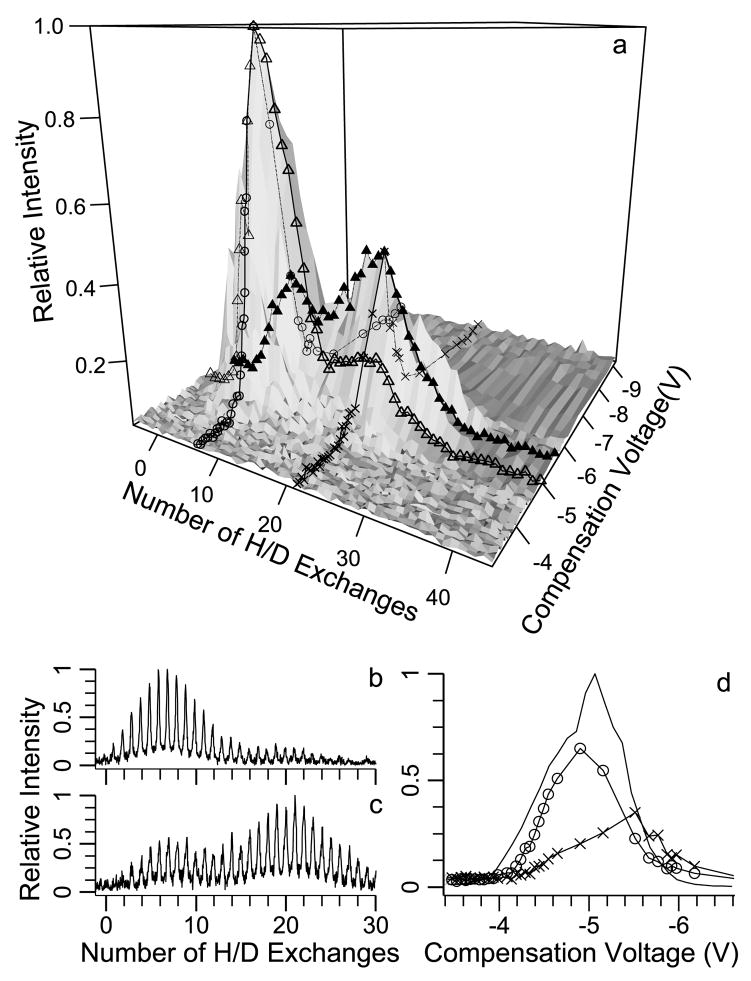

Results for the 10+ charge state are shown in Figure 5. The surface plot of the H/D exchange and CV scan data in Figure 5a indicates two local maxima. These maxima occur at CV values of −4.9 and −5.5 V with 7 and 21 deuteriums incorporated, respectively. In Figure 5b and c, the H/D exchange data at CV values of −4.9 and −5.5 V clearly show two resolved conformers, the relative abundances of which depend on the CV values. At a CV of −4.9 V, the abundance of the conformer that undergoes 7 exchanges is 3.9 times greater than that of the conformer that undergoes 21 exchanges. At a CV o f −5.5 V, the abundance of the lower exchanging conformer is only 0.8 times that of the higher exchanging conformer. From the surface plot data in Figure 5a, individual CV scans are constructed for the two conformers resolved by H/D exchange (Figure 5d). The conformers that undergo 7 and 21 exchanges have maxima at CV values of −4.9 and −5.5 V, respectively. Also shown in Figure 5d is the CV scan without H/D exchange. This CV scan with no H/D exchange has a broad peak with no obviously resolved conformers. Purves et al. reported two unresolved conformations for this charge state with a maximum at −5.35 V and the second conformation identified as a shoulder on the main peak at −4.95 V, consistent with our H/D exchange resolved CV scans.

Figure 5.

FAIMS-FT/ICR MS data for the 10+ charge state of bovine ubiquitin measured using 20 s H/D reaction time: (a) surface plot of CV values versus extents of H/D exchange, where lines marked with open triangles and filled triangles indicate H/D exchange distributions at CV values of −4.9 V and −5.5 V, respectively, and lines marked with open circles and letters x correspond to CV scans of the H/D exchange distribution with 7 and 21 deuteriums incorporated, respectively, (b) and (c) H/D exchange mass spectra at −4.9 V (b) and −5.5 V (c) and (d) CV scan with no H/D exchange (solid line) and with H/D exchange of the conformer that undergoes 7 exchanges (open circles) and 21 exchanges (letters x).

From the Figure 5 data, clearly the two conformers that undergo different extents of H/D exchange also have different collisional cross sections. Purves et al. measured cross sections of 1710 and 1670 Å2 for ions transmitted at CV values of −4.95 and −5.35 V, respectively. By comparison to these results, the conformer that undergoes 7 exchanges corresponds to an ion with a cross section of ~1710 Å2 and the conformer that undergoes 21 exchanges corresponds to an ion with a physical cross section of ~1670 Å2. Thus, the ion with the larger physical cross section undergoes less H/D exchange.

The CV scan for the 11+ charge state of ubiquitin has a peak at −5.4 V and a broad shoulder around −4.7 to −5.0 V indicating the presence of at least two conformations (Figure 6a). Purves et al. measured collisional cross sections of 1755 and 1770 Å2 at CV values of −5.35 and −5.0 V, respectively. In Figure 6b and c, H/D exchange spectra (40 s) are shown at CV values of −5.0 and −5.4 V. Three conformations are resolved by H/D exchange with average deuterium incorporation of 16, 30, and 45. The H/D distributions for this charge state do not change at different CV values. FAIMS results indicate at least two conformations and H/D exchange independently resolves three conformations.

Figure 6.

FAIMS-FT/ICR MS data for the 11+ charge state of bovine ubiquitin: (a) CV scan and spectra obtained at CV values of (b) −5.0 V and (c) −5.4 V with 40 s reaction time.

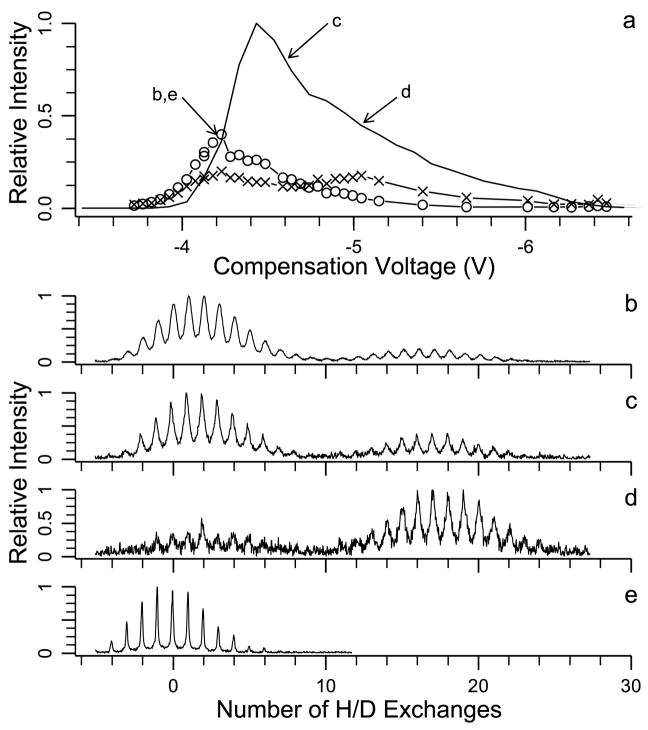

A CV scan (no H/D exchange) for the 12+ charge state shows a single broad peak with a maximum at −4.4 V (Figure 7a) H/D exchange (20 s) resolves two conformations with 2 and 17 deuteriums incorporated. As seen in Figure 7b, c, d, the relative abundance of the two distributions resolved by H/D exchange depend on the CV value. The relative abundance of the conformer that undergoes less exchange is greatest at −4.2 V (Figure 7b). The conformer that undergoes more exchange has a relative intensity maximum at −5.1 V (Figure 7d). Figure 7c shows a mass spectrum at an intermediate voltage of −4.6 V. A spectrum of the 12+ charge state with no exchange is shown for reference in Figure 7e.

Figure 7.

FAIMS-FT/ICR MS data for the 12+ charge state of bovine ubiquitin: (a) CV scan with no H/D exchange (solid line), conformer with 17 exchanges (letter x), and conformer with 2 exchanges (open circles) where b, c, d, and e indicate the compensation voltages at which the H/D exchange mass spectra were acquired (20 s reaction time for (b)–(d), no H/D exchange for (e).

Individual CV plots for both conformers resolved by H/D exchange can be reconstructed from these data and are shown in Figure 7a. The CV plot for the conformer that undergoes less exchange (2) has a maximum in CV transmission at −4.2 V. The CV scan of the conformer that undergoes more H/D exchange (17) has peaks at CV values of −4.2 and −5.1 V. This CV scan is similar to the CV scan obtained by Purves et al. who resolved two peaks at CV values of −4.55 and −5.05 V with measured collisional cross sections of 1905 and 1890 Å2, respectively. These results suggest that at least three conformers are present for the 12+ charge state. The two conformers that have a single measured cross section of 1905 Å2, correspond to H/D exchange distributions with 2 and 17 deuteriums incorporated. The ions with a more compact conformation or lower cross section of 1890 Å2 correspond to a third conformer that also undergoes 17 H/D exchanges. As observed for the 10+ charge state, a more compact conformer can undergo greater extent of H/D exchange.

For the 13+ charge state with 20 s o f H/D exchange, one distribution is observed with no deuteriums incorporated. We were unable to determine the extent of exchange at longer exchange times because of insufficient S/N. Marshal and coworkers also observed a single exchange distribution with 12 deuteriums incorporated at 3600 s [4]. The CV scan of the 13+ charge state has one peak at −4.6 V. Purves et al. also observed a single peak for the 13+ charge state at −4.65 V and this ion has a measured cross section of 1970 Å2. Multiple conformations for the 13+ have been resolved with FAIMS using a different carrier gas composition of 60/40 helium/nitrogen gas [20b]. McLafferty and coworkers also reported evidence of multiple conformations for the 13+ charge state based on evidence from ECD experiments [15d]. The 13+ charge state has the largest measured cross section, presumably due to having the most extended conformation, but this ion undergoes the least H/D exchange (at 20 s) of the charge states investigated. Presumably, this ion has the greatest surface accessibility, but undergoes the least H/D exchange.

Conclusions

For the ubiquitin ions of a given charge state, the extents of H/D exchange at short times (20–40 s ) d o not appear to be significantly correlated to ion cross sections. For the 8+, 9+, and 11+ charge states, the extents of H/D exchange do not depend on FAIMS CV values, but those of the 10+ and 12+ charge states do. For the latter charge states, the conformations that undergo the greatest extent of H/D exchange occur at CV values corresponding to conformations with lower cross section. This indicates that more compact conformers can undergo greater extents of H/D exchange. Factors other than surface accessibility or cross section appear to play an important role in determining the rate and extent of H/D exchange within these charge states. This result is consistent with the observation that H/D exchange extents of peptide dimers can be greater or less than those of the constituent monomers [16a].

Previously proposed mechanisms for H/D exchange indicate that an H/D exchange reagent, such as D2O, must form two simultaneous hydrogen bonds before H/D exchange [27, 28]. Such a “relay” mechanism [28] suggests that the observed decrease in H/D exchange for more extended conformers of a given charge state may be attributable to fewer possible multi-dentate interactions with the D2O.

Others have suggested that ubiquitin conformers with different charge states can be grouped into “families” of structures based on either collisional cross section or on H/D exchange extents. Although conformers with different charge states may be structurally very similar, our combined FAIMS and H/D exchange measurements suggest that grouping conformers into families based on a single physical property may oversimplify the complexity of these gas-phase conformers. FAIMS and H/D exchange can each resolve gas-phase conformations that are not resolved by the other technique and a combination of FAIMS and H/D exchange resolves more conformers than either method alone. These results suggest that H/D exchange and collision cross sectional measurements probe different properties of the gas-phase ubiquitin conformers. For the 12+ charge state, the two conformers (or conformer populations) have cross sections that differ by <1%, yet the H/D exchange extents (40 s) of these two conformers differ significantly (6 versus 25). For the 9+ charge state, the cross sections of the two conformers differ by 10%, yet only one conformer is observed by H/D exchange. There is the possibility that the longer time frame H/D exchange experiments probe the gas-phase conformations of the ubiquitin ions after they have isomerized to conformations not present during the time in which ions are transmitted through the FAIMS device. However, the dependence of H/D exchange on compensation voltage for the 10+ and 12+ charge states implies that at least some of the conformers originally separated by FAIMS survive and are probed by these H/D exchange experiments. Thus, the combination of FAIMS and H/D exchange provides a nearly orthogonal two-dimensional separation of the ubiquitin conformers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Roger Guevremont and Dr. Randy W. Purves for helpful discussions, and for generously sharing their expertise with FAIMS. The authors are grateful to Ionalytics Corporation for the loan of an Ionalytics Selectra FAIMS apparatus and to NIH for generous funding (R01-GM64712).

References

- 1.(a) Onuchic JN, LutheySchulten Z, Wolynes PG. Theory of Protein Folding: The Energy Landscape Perspective. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of Protein Folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton EA. The Protein Folding “Speel Limit”. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrold MF. Peptides and Proteins in the Vapor Phase. Ann Rev Phys Chem. 2000;51:179–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Suckau D, Shi Y, Beu SC, Senko MW, Quinn JP, Wampler FM, McLafferty FW. Coexisting Stable Conformations of Gaseous Protein Ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:790–793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McLafferty FW, Guan Z, Haupts U, Wood TD, Kelleher NL. Gaseous Conformational Structures of Cytochrome. c J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4732–4740. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wood TD, Chorush RA, Wampler FM, Little DP, O’Connor PB, McLafferty FW. Gas-Phase Folding and Unfolding of Cytochrome c Cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2451–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freitas MA, Hendrickson CL, Emmett MR, Marshall AG. Gas-Phase Bovine Ubiquitin Cation Conformations Resolved by Gas-Phase Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Rate and Extent. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999;185/186/187:565–575. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winger BE, Light-Wahl KJ, Rockwood AL, Smith RD. Probing Qualitative Conformation Differences of Multiply Protonated Gas-Phase Proteins via H/D Isotopic Exchange with D2O. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5897–5898. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Geller O, Lifshitz C. A Fast Flow Tube Study of Gas-Phase H/D Exchange of Multiply Protonated Ubiquitin. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:2217–2222. doi: 10.1021/jp044737c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans SE, Lueck N, Marzluff EM. Gas-Phase Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange of Proteins in an Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2003;222:175–187. [Google Scholar]; (c) Geller O, Lifshitz C. Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Kinetics of Cytochrome c: A n Electrospray Ionization Fast Flow Experiment. Isr J Chem. 2003;43:347–352. [Google Scholar]; (d) Valentine AE, Clemmer DE. Temperature-Dependent H/D Exchange of Compact and Elongated Cytochrome c Ions in the Gas Phase. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:506–517. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang F, Freitas MA, Marshall AG, Sykes BD. Gas-Phase Memory of Solution-Phase Protein Conformation: H/D Exchange and Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry of the N-Terminal Domain of Cardiac Troponin c. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999:192, 319–325. [Google Scholar]; (f) Wagner DS, Anderegg RJ. Conformation of Cytochrome c Studied by Deuterium Exchange Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1994;66:706–711. doi: 10.1021/ac00077a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Clemmer DE, Hudgins RR, Jarrold MF. Naked Protein Conformations—Cytochrome c in the Gas Phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10141–10142. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hudgins RR, Woenckhaus J, Jarrold MF. High Resolution Ion Mobility Measurements for Gas-Phase Proteins: Correlation Between Solution-Phase and Gas-Phase Conformations. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1997;165:497–507. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Wyttenbach T, vonHelden G, Bowers MT. Gas-Phase Conformation of Biological Molecules: Bradykinin. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8355–8364. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wyttenbach T, Kemper PR, Bowers MT. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2002;212:13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Badman ER, Hoaglund-Hyzer CS, Clemmer DE. Monitoring Structural Changes of Proteins in an Ion Trap Over ~10 to 200 ms: Unfolding Transitions in Cytochrome c Ions. Anal Chem. 2001;73:6000–6007. doi: 10.1021/ac010744a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Myung S, Badman ER, Lee YJ, Clemmer DE. Structural Transitions of Electrosprayed Ubiquitin Ions Stored in an Ion Trap over ~10 ms to 30 s. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:9976–9982. [Google Scholar]; (c) Li J, Taraszka JA, Counterman AE, Clemmer DE. Influence of Solvent Composition and Capillary Temperature on the Conformations of Electrosprayed Ions: Unfolding of Conpact Ubiquitin Conformers from Pseudonative and Denatured Solutions. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999;185/186/187:37–47. [Google Scholar]; (d) Valentine SJ, Anderson JG, Ellington AD, Clemmer DE. Disulfide-Intact and -Reduced Lysozyme in the Gas Phase: Conformations and Pathways of Folding and Unfolding. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:3891–3900. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Gross DS, Schnier PD, Rodriguez-Cruz SE, Fagerquist CK, Williams ER. Conformations and Folding of Lysozyme Ions in Vacuo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3143–3148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang X, Cassady CJ. Apparent Gas-Phase Acidities of Multiply Protonated Peptide Ions: Ubiquitin, Insulin B, and Renin Substrate. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(96)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Valentine SJ, Counterman AE, Clemmer DE. Conformer-Dependent Proton Transfer Reactions of Ubquitin Ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1997;8:954–961. [Google Scholar]; (d) Loo RRO, Loo JA, Udseth HR, Fulton JL, Smith RD. Protein Structural Effects in Gas-Phase Ion Molecule Reactions with Diethylamine. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1992;6:159–165. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290060302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Reimann CT, Sullivan PA, Axelsson J, Quist AP, Altmann S, Roepstorff P, Velazquez I, Tapia O. Conformation of Highly-Charged Gas-Phase Lysozyme Revealed by Energetic Surface Imprinting. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7608–7616. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sullivan PA, Axelsson J, Altmann S, Quist AP, Sunqvist BUR, Reimann CT. Defect Formation on Surfaces Bombarded by Energetic Multiply Charged Proteins: Implications for the Conformation of Gas-Phase Electrosprayed Ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:329–341. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Arteca GA, Reimann CT, Tapia O. Proteins in Vacuo: Denaturing and Folding Mechanisms Studied with Computer-Simulated Molecular Dynamics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2001;20:402–422. doi: 10.1002/mas.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mao Y, Ratner MA, Jarrold MF. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Charge-Induced Unfolding and Refolding of Unsolvated Cytochrome. c J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:10017–10021. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu DF, Wyttenbach T, Carpenter CJ, Bowers MT. Investigation of Noncovalent Interactions in Deprotonated Peptides: Structural and Energetic Competition Between Aggregation and Hydration. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3261–3270. doi: 10.1021/ja0393628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Covey T, Douglas DJ. Collision Cross-Sections for Protein Ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1993;4:616–623. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(93)85025-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cox KA, Julian RK, Cooks RG, Kaiser RE. Conformer Selection of Protein Ions by Ion Mobility in a Triple Quadrupole Mass-Spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:127–136. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Moradian A, Scalf M, Westphall MS, Smith LM, Douglas DJ. Collision Cross-Sections of Gas-Phase DNA Ions. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2002;219:161–170. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purves RW, Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R. Investigation of Bovine Ubiquitin Conformers Separated by High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry: Cross Section Measurements Using Energy-Loss Experiments with a Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:738–745. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Wu GY, Van Orden S, Cheng XH, Bakhtiar R, Smith RD. Characterization of Cytochrome-c Variants with High-Resolution FT/ICR Mass Spectrometry—Correlation of Fragmentation and Structure. Anal Chem. 1995;67:2498–2509. doi: 10.1021/ac00110a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cassady CJ, Carr SR. Elucidation of Isomeric Structures for Ubiquitin [M+12H] (12+) Ions Produced by Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:247–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199603)31:3<247::AID-JMS285>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kaltashov IA, Fenselau C. Stability of Secondary Structural Elements in a Solvent-Free Environment: The Alpha Helix. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 1997;27:165–170. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199702)27:2<165::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Breuker K, Oh H, Horn DM, Cerda BA, McLafferty FW. Detailed Unfolding and Folding of Gaseous Ubiquitin Ions Characterized by Electron Capture Dissociation. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6407–6420. doi: 10.1021/ja012267j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Badman ER, Myung S, Clemmer DE. Dissociation of Different Conformations of Ubquitin Ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:719–723. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Van Den Bremer ETJ, Jiskoot W, James R, Moore GR, Kleanthous C, Heck AJR, Maier CS. Probing Metal Ion Binding and Conformational Properties of the Colicin E9 Endonuclease by Electrospray Time-of-Flight Mass Ionization Spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1738–1752. doi: 10.1110/ps.0200502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Oh H, Breuker K, Sze SK, Ge Y, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Secondary and Tertiary Structures of Gaseous Protein Ions Characterized by Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry and Photofragment Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15863–15868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212643599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Jurchen JC, Cooper RE, Williams ER. The Role of Acidic Residues and of Sodium Ion Adduction on the Gas-Phase H/D Exchange of Peptides and Peptide Dimers. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:1477–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cox HA, Julian RR, Sang-Won L, Beauchamp JL. Gas-Phase H/D exchange of Sodiated Glycine Oligomers with ND3: Exchange Kinetics Do Not Reflect Parent Ion Structures. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6485–6490. doi: 10.1021/ja049834y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Freitas MA, Marshall AG. Rate and Extent of Gas-Phase Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange of Bradykinins: Evidence for Peptide Zwitterions in the Gas Phase. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999;183:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Bowers MT, Kemper PR, von Helden G, van Koppen PAM. Gas-Phase Ion Chromatography-Transition-Metal State Selection and Carbon Cluster Formation. Science. 1993;260:1446–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5113.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Clemmer DE, Jarrold MF. Ion Mobility Measurements and Their Applications to Clusters and Biomolecules. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:577–592. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentine SJ, Clemmer DE. H/D Exchange Levels of Shape-Resolved Cytochrome c Conformers in the Gas Phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:3558–3566. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Buryakov IA, Krylov EV, Nazarov EG, Rasulev UK. A New Method of Separation of Multi-Atomic Ions by Mobility at Atmospheric Pressure Using a High-Frequency Amplitude-Asymmetric Strong Electric Field. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1993;128:143–148. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buryakov IA, Krylov EV, Makas AL, Nazarov EG, Pervukhin VV, Rasulev UK. Separation of Ions According to Mobility in Strong AC Fields. Sov Tech Phys Lett. 1991;17:446–447. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Purves RW, Barnett DA, Guevremont R. Separation of Protein Conformers Using Electrospray-High Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2000;197:163–177. [Google Scholar]; (b) Purves RW, Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R. Elongated Conformers of the charge states +11 to +15 of Bovine Ubiquitin Studied using ESI-FAIMS-MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2001;12:894–901. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Purves RW, Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R. Gas-Phase Conformations of the [M + 2H]++ Ion of Bradykinin Investigated by Combining High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry, Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange, and Energy-Loss Measurements. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1453–1456. doi: 10.1002/rcm.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Borysik AJH, Read P, Little DR, Bateman RH, Radford SE, Ashcroft AE. Separation of β2-Microglobulin Conformers by High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) Coupled to Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2229–2234. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Purves RW, Guevremont R, Day S, Pipich CW, Matyjaszczyk MS. Mass Spectrometric Characterization of a High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometer. Rev Sci Instrum. 1998;69:4094–4105. [Google Scholar]; (b) Guevremont R, Purves RW. Atmospheric Pressure Ion Focusing in a High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometer. Rev Sci Instrum. 1999;70:1370–1384. [Google Scholar]; (c) Krylov EV. A Method of Reducing Diffusion Losses in a Drift Spectrometer. Tech Phys. 1999;44:113–116. [Google Scholar]; (d) Guevremont R, Purves RW, Barnett DA, Ding L. Ion Trapping at Atmospheric Pressure (760 Torr) and Room Temperature with a High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999;193:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurchen JC, Williams ER. Origin of Asymmetric Charge Partitioning in the Dissociation of Gas-Phase Protein Homodimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2817–2826. doi: 10.1021/ja0211508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Beu SC, Laude DA. Open Trapped Ion Cell Geometries for Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1992;112:215–230. [Google Scholar]; (b) Guan SH, Marshall AG. Ion Traps for Fourier-Transform Ion-Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry—Principles and Design of Geometric and Electronic Configurations. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1995;146:241–296. [Google Scholar]; (c) Vartanian VH, Laude DA. Optimization of a Fixed-Volume Open Geometry Trapped Ion Cell for Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Mass Spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1995;141:189–200. [Google Scholar]; (d) Easterling ML, Mize TH, Amster IJ. MALDI FTMS Analysis of Polymers: Improved Performance Using an Open Ended Cylindrical Analyzer Cell. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1997;169:387–400. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kuhnen F, Spiess I, Wanczek KP. Theoretical Comparison of Closed and Open ICR Cells. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1997;167:761–769. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Beu SC, Laude DA. Elimination of Axial Ejection During Excitation with a Capacitively Coupled Open Trapped-Ion Cell for Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1992;64:177–180. [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Conner PB, McLafferty FW. High-Resolution Ion Isolation with the Ion Cyclotron Resonance Capacitively Coupled Open Cell. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1995;6:533–535. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2004. 2004, version 2.0.1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R, Purves RW, Viehland LA. Evaluation of Carrier Gases for use in High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spangler GE, Raanan AM. Application of Mobility Theory to the Interpretation of Data Generated by Linear and RF Excited Ion Mobility Spectrometers. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2002;214:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Gard E, Willard D, Bregar J, Green MK, Lebrilla CB. Site-Specificity in the H/D Exchange Reactions of Gas-Phase Protonated Amino-Acids with CH3OD. Org Mass Spectrom. 1993;28:1632–1639. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gard E, Green MK, Bregar J, Lebrilla CB. Gas-Phase Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange as a Molecular Probe for the Interaction of Methanol and Protonated Peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:623–631. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Green MK, Lebrilla CB. The Role of Proton-Bridged Intermediates in Promoting Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange in Gas-Phase Protonated Diamines, Peptides, and Proteins. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1998;175:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Campbell S, Rodgers MT, Marzluff EM, Beauchamp JL. Structural and Energetic Constraints on Gas-Phase Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Reactions of Protonated Peptides with D2O, CD3OD, CD3CO2D, and ND3. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:9765–9766. [Google Scholar]; (b) Campbell S, Rodgers MT, Marzluff EM, Beauchamp JL. Deuterium Exchange Reactions as a Probe of Biomolecule Structure. Fundamental Studies of Gas Phase H/D Exchange Reactions of Protonated Glycine Oligomers with D2O, CD3OD, CD3CO2D, and ND3. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:12840–12854. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee SW, Lee HN, Kim HS, Beauchamp JL. Selective Binding of Crown Ethers to Protonated Peptides Can Be Used to Probe Mechanisms of H/D Exchange and Collision-Induced Dissociation Reactions in the Gas Phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5800–5805. [Google Scholar]