Abstract

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) are decreased in the corticospinal tract of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS); to determine if T2 is increased in corticospinal tract or reduced in motor cortex in ALS; to determine if corticospinal tract MTR correlates with a clinical measure of motor neuron function in ALS. Ten ALS patients and 17 age-matched controls were studied. Double spin echo MRI and 3D gradient echo MRI with and without off-resonance saturation were acquired on each subject. 3D data sets were coregistered and resliced to match the spin echo data set. MTR was calculated for corticospinal and non-corticospinal tract white matter. T2 was calculated for corticospinal and non-corticospinal tract white matter, motor cortex and non-motor cortex. MTR was reduced by 2.6% (p < .02) in corticospinal, but not in non-corticospinal, tract white matter in ALS. There was no difference in T2 in any brain region. The correlation between a clinical measure of motor neuron function and corticospinal tract MTR was statistically significant. These findings are consistent with the known pathology in ALS and suggest that MTR is more sensitive than T2 for detecting involvement of the corticospinal tract. Quantitative MTR of the corticospinal tract may be a useful, objective marker of upper motor neuron pathology in ALS.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Magnetization transfer ratio, T2 relaxation, Corticospinal tract, Motor cortex

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a degenerative disease of unknown etiology which affects upper and lower motor neurons of middle-aged to elderly adults. The prevalence of sporadic ALS is about five cases in 100,000, and there are no treatments which arrest or reverse the disease.1 Promising drug treatments make it important to identify quantitative indices of disease severity to monitor therapy.2 A problem in clinical management and drug treatment trials of ALS is that most measures of upper motor neuron disease rely on patient performance and are thus influenced by motivation and other uncontrollable factors. Therefore, objective markers of upper motor neuron disease are needed for diagnosis and to monitor the effects of treatment.

The primary role of MRI in the work-up of ALS is to exclude other causes of motor system disease. Some investigators have described hyperintense signal on proton density and T2 weighted images in the corticospinal tract of subjects with ALS,3–6 but this finding is not sensitive. Goodin et al.3 reported corticospinal tract hyperintensity in only two of five, and Terao et al.4 in only four of 13 ALS subjects. The magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) is an MR parameter that measures exchange of magnetization between free protons and those bound to macromolecules and is thus thought to reflect alterations in macromolecular structure.7 Reductions in MTR without detectable changes on proton density or T2-weighted images have been observed experimentally in axonal degeneration;8 therefore, MTR may be useful for detecting degeneration of corticospinal tract fibers known to occur in ALS.

Another qualitative MRI finding described in ALS is hypointensity in the precentral motor cortex on T2 weighted images.9–11 However, neither the sensitivity5 nor the specificity12 of this finding has been reproduced consistently. Furthermore, areas of low signal intensity on T2 weighted images are common in normal aging, in neurological diseases other than ALS, and are particularly frequent in the motor cortex.12

The purpose of this study was to 1) test the hypothesis that MTR of the corticospinal tract white matter is reduced in ALS compared to controls; 2) to determine if T2 is increased in corticospinal tract or decreased in motor cortex in ALS patients compared to controls; and 3) to determine if corticospinal tract MTR correlates with clinical measures of upper motor neuron function in ALS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Ten patients (1F, 9M) with clinically definite or probable ALS aged 21 to 70 years (mean ± 1 SD; 52 ± 15 years) and 17 neurologically normal age-matched controls (5F, 12M) aged 22−81 years (47 ± 16 years) were studied. All subjects had MR imaging and spectroscopy examinations as part of another project. The diagnosis was made by two experienced neurologists (RM, DG) according to criteria derived from the World Federation of Neurology consensus meeting at El Escorial, Spain.13 Maximum finger and foot tap rates were acquired as a clinical measure of motor neuron function. Finger tap rate was measured by having the subject place the wrist on the table edge and tapping the forefinger on the tabletop as rapidly as possible for 10 seconds. Foot tap rate was obtained by having the subject seated in a chair and tapping the foot as rapidly as possible for 10 seconds. Maximum rates were obtained by dividing total taps by 10 seconds. Finger and foot tap rates were correlated with MTR of the contralateral corticospinal tract.

MRI Acquisition

MRI was performed on a 1.5T system (Siemen's Vision, Erlangen, Germany) using a head coil with quadrature detection. Three MRI sequences were acquired; 1) T1 weighted sagittal localizer; 2) Double spin echo (TR 2500/TE 20,80) in the axial orientation, full brain coverage, 3 mm slice thickness, no slice gaps, and 1 mm2 in-plane resolution; and 3) 3D gradient echo (GRE) (TR 50/TE 6), flip angle 15°, with and without magnetization transfer, 3-mm thick slice partitions in the axial plane, 1-mm2 in-plane resolution. The sequence was intermediate between T1 and proton density weighted. Saturation was achieved by application of an 8-ms Gaussian pulse with a magnitude of 4 μT, 2 kHz off-resonance of the water peak. The specific absorption rate was below the FDA limits for all subjects.

MRI Analysis

Qualitative analysis

A neuroradiologist (JT) blinded to the subjects’ diagnoses evaluated the proton density weighted images for the presence of three MRI findings thought to be relatively specific for ALS: i) motor cortex atrophy out of proportion to global atrophy; ii) motor cortex hypointensity; and iii) corticospinal tract hyperintensity. The MRI was called “abnormal” if at least one of these three abnormalities was identified.

MTR and T2 analysis

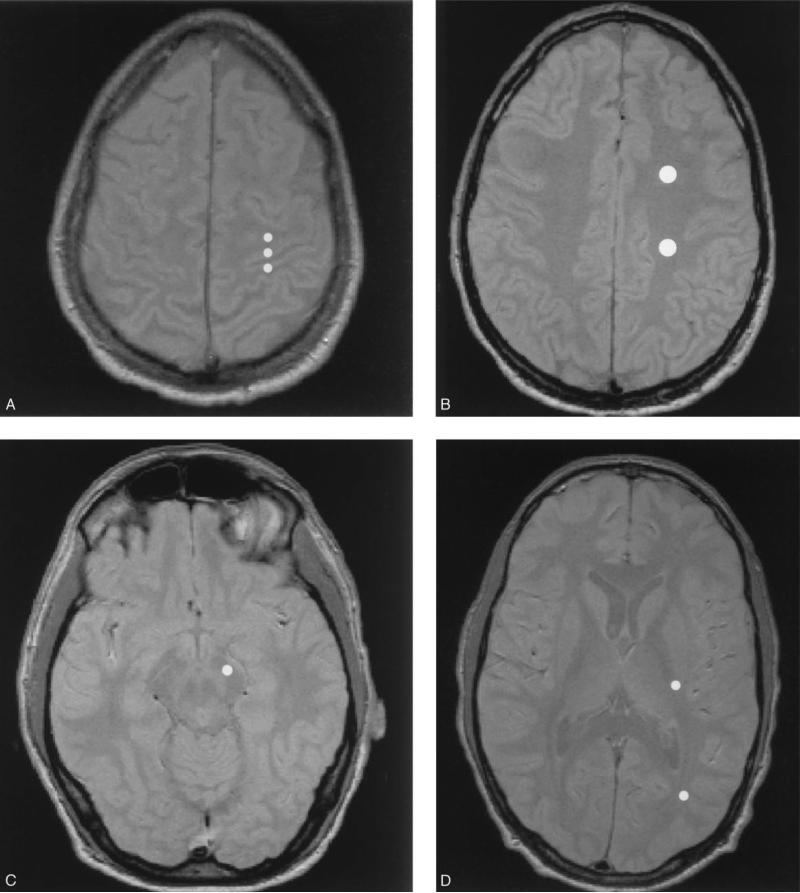

The 3D-GRE data sets were coregistered and resliced to match the spin echo images using Wood's algorithm.14 Eight regions of interest were manually selected by a single observer (JT) using the proton density weighted MRI as a guide as shown in Fig. 1: 1) pre-central motor cortex; 2) post-central sensory cortex; 3) perirolandic white matter anterior and adjacent to the motor cortex; 4) anterior centrum semiovale; 5) posterior centrum semiovale; 6) posterior aspect of the posterior limb of the internal capsule; 7) midbrain corticospinal tract; and 8) occipital white matter (Fig. 1). Four white matter regions-of-interest (perirolandic, posterior centrum semiovale, posterior internal capsule, and midbrain corticospinal tract) were averaged for an overall measure of corticospinal tract white matter. Two white matter regions-of-interest (anterior centrum semiovale and occipital white matter) were averaged for an overall measure of non-corticospinal tract white matter. The MTR was computed for each region-of-interest using MTR = (1 – MMT/M0)* 100 where M0 = signal intensity without MT, MMT = signal intensity with MT. T2 values were calculated from the double spin echo MRI using T2 = Δ/ln(STE1/STE2), where STE1 = signal intensity of first echo (TE = 20 ms), STE2 = signal intensity of the second echo (TE = 80 ms), and Δ = difference in TE (60 ms). Right and left sides were averaged together for analysis by group and analyzed separately for correlation with clinical measures.

Fig. 1.

Regions-of-interest (ROI) were placed using the proton density weighted image as a guide (shown only in one hemisphere). From top to bottom: A) peri-rolandic white matter, pre-central motor cortex, post-central sensory cortex; B) anterior and posterior centrum semiovale; C) posterior internal capsule, occipital white matter; D) midbrain corticospinal tract. Four ROIs (peri-rolandic, posterior centrum semiovale, posterior internal capsule, and midbrain corticospinal) were combined for an overall corticospinal tract measure.

Statistical analysis

The data met conditions of equal variance and normality. Therefore, a student's t-test was used to analyze differences in MTR of corticospinal and non-corticospinal tract white matter. One-tailed t-test was performed because we expected MTR to be lower in ALS subjects. Regional differences in T2 were compared using a t-test corrected for multiple comparisons. Correlation between maximum finger and foot tap rate and MTR of corticospinal tract was performed using Pearson correlation coefficient. Qualitative MRI scores for ALS subjects were compared to those of controls using Fisher Exact test.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes demographic information, finger and foot tap rates, and qualitative MRI readings for each ALS patient.

Table 1.

Demographic data and MRI qualitative reading for ALS subjects

| Tap rate (s−1) |

MRI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Sex | Foot | Finger | MC atrophy | CST ↑SI | MC ↓SI | |

| 1 | 70/M | 1.6 | 1.6 | + | + | + |

| 2 | 21/M | 1.6 | 2.2 | − | − | − |

| 3 | 45/M | 2.4 | .9 | + | − | − |

| 4 | 46/M | 0 | 0 | + | + | − |

| 5 | 44/M | 4.4 | 4 | + | − | − |

| 6 | 64/M | 1.5 | 4.1 | + | − | − |

| 7 | 47/M | 1 | 2.2 | − | − | − |

| 8 | 62/M | 1.9 | 4.4 | − | − | − |

| 9 | 55/F | 0 | 4 | + | + | + |

| 10 | 69/M | .8 | 4.3 | − | − | + |

MC = motor cortex, CST = corticospinal tract, SI = signal intensity.

Tap rates are averaged over right and left.

Table 2 summarizes MTR and T2 values for the regions-of-interest. There was a significant reduction (2.6%) in MTR in the corticospinal tract white matter, but not in non-corticospinal tract white matter ( p < 0.02) in ALS compared to controls. Although the magnitude of the difference is small, the effect size (0.85) is relatively large. There was no significant difference in T2 in any brain region between ALS subjects and controls.

Table 2.

Magnetization transfer ratio and T2 in brain regions in ALS compared to controls

| MTR |

T2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS (n = 10) | C (n = 17) | p | ALS (n = 10) | C (n = 17) | p | |

| CST WM | 40.7 ± 1.7 | 41.8 ± 0.9 | .019 | 67.9 ± 3.8 | 68.0 ± 1.8 | ns |

| Non-CST WM | 41.9 ± 1.4 | 42.4 ± 0.9 | ns | 65.5 ± 2.6 | 64.9 ± 2.2 | ns |

| Motor cortex | — | — | — | 75.3 ± 9.2 | 76.5 ± 7.7 | ns |

| Non-motor cortex | — | — | — | 66.2 ± 6.7 | 65.7 ± 7.1 | ns |

mean ± 1 standard deviation; T2 in ms; ns = p > 0.10.

CST WM = corticospinal tract white matter.

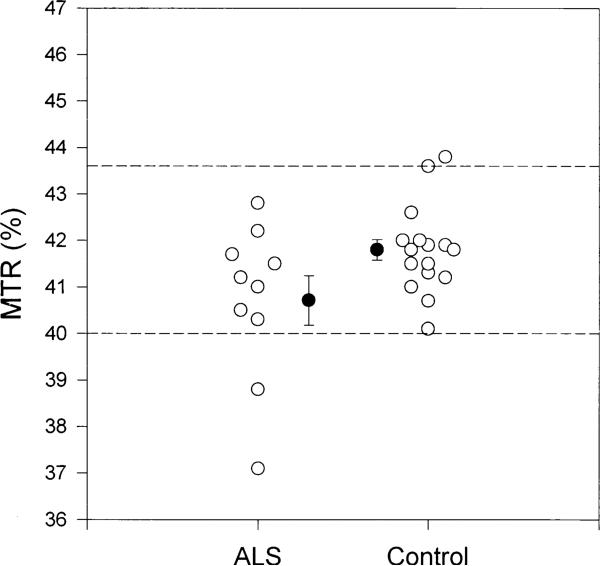

Figure 2 shows the MTR measurements in corticospinal tract white matter for each ALS subject and control. The mean MTR was lower in ALS subjects compared to controls. The 95% confidence interval for controls (dashed reference lines) shows that two ALS subjects fell outside the interval.

Fig. 2.

Magnetization transfer ratios (%) in the CST white matter in ALS subjects and controls. Each open circle represents an individual. Mean, standard error, and 95% confidence interval are shown.

Table 3 summarizes qualitative MRI reading in ALS and controls. There was no difference in frequency of “abnormal” MRI.

Table 3.

Qualitative MRI reading for ALS and controls

| Normal MRI | Abnormal MRI | |

|---|---|---|

| ALS | 3 | 7 |

| Control | 12 | 5 |

p = n.s., Fisher Exact Test.

Abnormal MRI was based on ALS specific findings (see Methods for details).

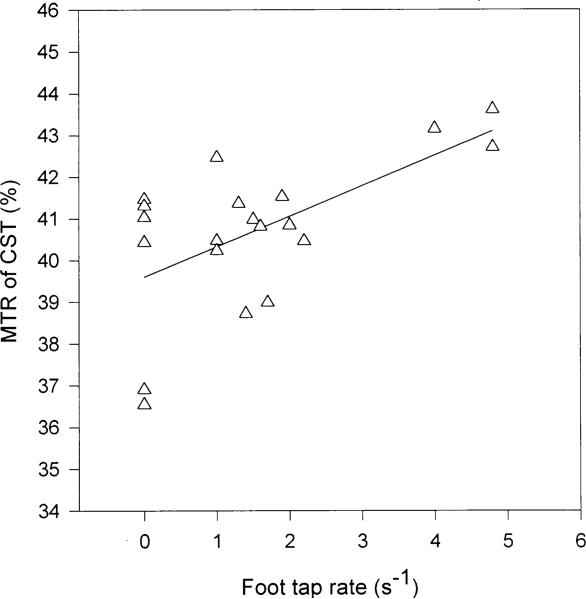

Correlations between MTR in the corticospinal tract white matter and foot-tap rate (r = 0.61, p < 0.005) (Fig. 3) and finger-tap rate (r = 0.39, p < 0.05) (data not shown) were statistically significant in ALS subjects.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between MTR of the CST in ALS subjects and maximum foot-tap rate (r = 0.61, p < 0.005). Rates were correlated with the MTR measurements obtained in the contralateral CST.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of these experiments were that: 1) there was a significant reduction in the magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) of the corticospinal tract white matter in ALS subjects compared to controls; 2) there was no significant difference in quantitative T2 in either corticospinal tract or motor cortex in ALS subjects compared to controls; 3) there was a significant correlation between MTR of the corticospinal tract white matter and a clinical measure of motor neuron function in ALS; and 4) there was no significant difference in the qualitative MRI findings in ALS subjects compared to controls. Taken together, these findings suggest that quantitative MTR reflects the known pathology of axonal degeneration in the corticospinal tract and may be a useful, objective marker of upper motor neuron involvement in ALS.

The first major finding is that MTR was significantly reduced in the corticospinal tract white matter but not in non-corticospinal white matter in subjects with ALS. Although the magnitude of the reduction in MTR is small (2.6%), the effect size (0.85) is relatively large due to the low variance that is characteristic of MTR measurements. These findings are consistent with the pathological features of ALS. Degeneration of the corticospinal tracts is usually found in the lower portions of the spinal cord and medulla. In many cases, the process extends further superiorly through the posterior limb of the internal capsule, into the corona radiata, and finally to the motor cortex.1 Pathological examination reveals axonal degeneration and myelin breakdown, processes that are both associated with reductions in MTR.8,15 Similarly, Kato et al. also found significant reductions in pyramidal tract MTR in nine subjects with ALS, although the magnitude of the MTR differences was larger in their study compared to ours (20% vs. 2%).16 There are several technical explanations for this difference. First, their MTR measurements reflected more T1 relaxation than ours; thus, any process that reduces T1 would result in a lower MTR. Second, differences in the saturation pulse will cause differences in MTR, depending on the strength of the pulse and extent of unwanted direct saturation. Third, we sampled several regions along the corticospinal tract in a blinded manner, while Kato et al. sampled only one region (posterior limb of the internal capsule). Fourth, to ensure proper selection and placement of the regions-of-interest, we coregistered and resliced the MTR data sets to match the spin echo datasets upon which circular regions-of-interest were placed while the previous study did not. In contrast to differences in MTR, Segawa et al. reported no difference in MTR of the corticospinal tract.17 Such inconsistencies may arise from the notion that ALS is not a single pathological entity, but a spectrum of motor system abnormalities that always involves lower, and usually, but not always, involves upper motor neurons. A large, retrospective, pathological study performed by Brownell et al.18 in 1970 supports the view that motor neuron disease is not a well-defined entity, but a spectrum of heterogeneous multiple system atrophies that have a predilection for certain parts of the motor system. They studied 45 cases of “classical motor neuron disease” and found that all subjects were afflicted with progressive loss of lower motor neurons and that most of them also showed degenerative changes involving the pyramidal system.18

The second major finding is that there was no significant difference in T2 in either the corticospinal tract or the motor cortex of ALS (Table 2). These results indicate that quantitative MR-measured T2 in these brain regions is not a sensitive marker for ALS. Several previous studies have found hyperintense signal on proton density and T2 weighted images in the corticospinal tract3–5,10,19 in ALS, suggesting that T2 relaxation time is increased in the corticospinal tract. Only one previous study measured quantitative T2 in the corticospinal tract and found results similar to ours.17 Segawa et al. found no difference in quantitative T2 in several brain regions including corticospinal tract and motor cortex. These same investigators reported an increase in spin density in the corticospinal tract of ALS. The significance of these results is unclear as we know of no pathological models which can account for an increase in spin density without an increase in T2. In contrast to the increased signal intensity observed in the corticospinal tract in ALS, decreased signal intensity in the precentral motor cortex has been observed on T2 weighted images in ALS.9–11 Oba et al. reported T2 hypointensity in the motor cortex in 14 of 15 ALS patients and in only 1 of 49 controls, suggesting high sensitivity and specificity.9 These findings suggest that T2 relaxation time is decreased in the motor cortex. On the contrary, we did not observe a group difference in T2 relaxation in the motor cortex. Consistent with this lack of quantitative T2 change, qualitative assessment revealed motor cortex hypointensity in only 3 of 10 ALS subjects. Further studies are needed to test the usefulness of this finding in the diagnosis of ALS. Another caveat is that areas of low signal intensity have been observed in neurodegenerative diseases other than ALS, as well as in normal aging. Imon et al. found that cortical “low intensity areas” were common in subjects over 50 years and occurred with greatest frequency in motor cortex.12

The third finding was that in ALS patients, MTR of the corticospinal tract was significantly correlated with foot and finger tap rates (Fig. 3). Rapid, repetitive contractions such as finger and foot tapping may be used as an index of upper motor neuron function.20 Our results suggest that MTR of the corticospinal tract may have potential use as an objective marker of upper motor neuron function.

The last finding was that there was no significant difference in qualitative MRI readings in ALS (Table 3). By contrast, Cheung et al. found significant differences in qualitative MRI ratings between ALS and controls. In their study, MR images were evaluated for hyperintensity in the corticospinal tract on proton density weighted images and atrophy of the motor cortex out of proportion to global atrophy.10

The major limitation to this study is the relatively small number of subjects with ALS. Additional studies are needed to test the robustness of our findings. A second limitation mentioned above is that MTR measurements of most biological processes have a small dynamic range; consequently, the magnitude of MTR changes one can expect to measure is small. It is important to bear in mind that other quantitative imaging techniques such as PET21 and MR spectroscopy22,23 have shown a greater magnitude of changes in ALS than those reported herein.

In summary, we found a significant reduction in MTR of the corticospinal tract and no change in quantitative T2 in either the corticospinal tract or in motor cortex of subjects with ALS. These findings suggest that MTR of the corticospinal tract white matter is more sensitive than T2 and qualitative MRI interpretation as a marker of upper motor neuron involvement in ALS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Research Service Award DA-05683−02 (J.L.T.), by a research grant from The Forbes Norris MDA/ALS Research Center (R.G.M.), and by the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service (M.W.W.) National Institutes of Health Grant R01AG10897 (M.W.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Davis RL, Roberts DM, editors. Textbook of Neuropathology. Williams and Wilkins; Maryland: 1991. pp. 946–949. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bensimon G, Lacomblex L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;330:585–591. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodin DS, Rowley HA, Olney RK. Magnetic resonance imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1988;23:418–420. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terao S, Sobue G, Yasuda T, Kachi T, Takahashi M, Mitsuma T. Magnetic resonance imaging of the corticospinal tracts in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995;133:66–72. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00143-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carella F, Grisoli M, Savoiardo M, Testa D. Magnetic resonance signal abnormalities along the pyramidal tracts in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995;16:511–515. doi: 10.1007/BF02282908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sales Luis ML, Hormigo A, Mauricio C, Alves MM, Serrao R. Magnetic resonance imaging in motor neuron disease. J. Neurol. 1990;237:471–474. doi: 10.1007/BF00314764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer imaging: practical aspects and clinical applications. Radiology. 1994;192(3):593–599. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.3.8058919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lexa F, Grossman RI, Rosenquist AC. MR of wallerian degeneration in the feline visual system: Characterization by magnetization transfer rate with histopathologic correlation. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1994;15:201–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oba H, Araki T, Ohtomo K, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: T2 shortening in motor cortex imaging. Radiology. 1993;189:843–846. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.3.8234713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung G, Gawal MJ, Cooper PW, Farb RI, Ang LC. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: correlation of clinical and MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1995;194:263–270. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.1.7997565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa K, Nagura H, Yokota T, Yamanouchi H. Signal loss in the motor cortex on magnetic resonance images in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:218–222. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imon Y, Yamaguchi S, Yamamura Y, et al. Low intensity areas observed on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the cerebral cortex in various neurological diseases. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995;134(Suppl):27–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00205-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Disease/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis workshop contributors. J. Neurol. Sci. 1994;124(Suppl):96–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1992;16:620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman RI. Magnetization transfer in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1994;36:S97–S99. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato Y, Matsumura K, Kinosada Y, Narita Y, Kuzuhara S, Nakagawa T. Detection of pyramidal tract lesions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with magnetization transfer measurements. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1541–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segawa F, Kinoshita M, Kishibayashi J, Sunohara N, Shimizu K. MRI of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Wallerian Degeneration—analysis of diffusion coefficient and magnetization transfer.. Book of abstracts: Second Annual Meeting of Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Nice, France. 1994.p. 1299. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownell B, Oppenheimer DR, Hughes JT. The central nervous system in motor neurone disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psych. 1970;33:338–357. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.33.3.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman D, Tartaglino LM. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Hyperintensity of the corticospinal tracts on MR images of the spinal cord. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993;160:604–606. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.3.8430564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller RG, Moussavi RS, Green AT, Carson PJ, Weiner MW. The fatigue of rapid repetitive movements. Neurology. 1993;43:755–761. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kew JJM, Leigh PN, Playford ED, et al. Cortical function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A positron emission tomography study. Brain. 1993;116:655–6801. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rooney WD, Miller RG, Gelinas D, Schuff N, Maudsley AA, Weiner MW. Decreased motor cortex N-acetylaspartate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.. Book of abstracts: Fifth Annual Meeting of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Vancouver, BC. 1997.p. 1189. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pioro EP, Antel JP, Cashman NR, Arnold DL. Detection of cortical neuron loss in motor neuron disease by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in vivo. Neurology. 1994;44:1933–1938. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.10.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]