Summary

Purpose

We compared the 31P metabolites in different brain regions of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) with those from controls.

Methods

Ten control subjects and 11 patients with TLE were investigated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and [31P]MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). [31P]MR spectra were selected from a variety of brain regions inside and outside the temporal lobe.

Results

There were no asymmetries of inorganic phosphate (Pi), pH, or phosphomonoesters (PME) between regions in the left and right hemispheres of controls. In patients with TLE, Pi and pH were higher and PME was lower throughout the entire ipsilateral temporal lobe as compared with the contralateral side and there were no significant asymmetries outside the temporal lobe. The degree of ipsilateral/contralateral asymmetry for all three metabolites was substantially greater for the temporal lobe than for the frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes, and these asymmetries provided additional data for seizure localization. As compared with levels in controls, Pi and pH were increased and PME were decreased on the ipsilateral side in patients with TLE. There were changes in Pi, pH, and PME on the contralateral side in persons with epilepsy as compared with controls, contrary to changes on the ipsilateral side.

Conclusions

Our findings provide some insight into the metabolic changes that occur in TLE and may prove useful adjuncts for seizure focus lateralization or localization.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging, Phosphorus metabolism, Focal epilepsy, Localization

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), with mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) as the pathology, is a common neurological disorder of unknown etiology (1,2). Current diagnostic tests to lateralize and localize the seizure focus include scalp and depth electrode EEG, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission CT (SPECT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (3-5). MRI is abnormal in ∼60−70% of cases with MTS (2-5) and is more sensitive than CT (6-8). Patients with unilateral hippocampal atrophy or increased hippocampal T2, signal intensity concordant with the ictal EEG focus have ∼90% chance of becoming seizure-free after temporal lobectomy (9). However, in patients with a normal MRI scan (i.e., not concordant), the prognosis for a seizure-free outcome is ≤50% (10). PET with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) has also been used to lateralize the seizure focus, showing hypometabolism of the temporal lobe with an incidence of 60−90% (7,11,12). However, the hypometabolic zone in PET scans in patients with TLE is usually larger than the underlying lesion and the region that generates the epileptic seizures (13). Interictal SPECT shows decreased regional cerebral blood flow in 40−80% of all patients with TLE (14-17), but has a high frequency of false positives (11).

Phosphorous (31P) MR spectroscopy (MRS) noninvasively detects a variety of 31P metabolites, including ATP, phosphocreatine (PCr), inorganic phosphate (Pi), phosphomonoesters (PME), and phosphodiesters (PDE); in addition, the pH may be determined from the chemical shift of the Pi resonance (18). Most previous studies using MRS were performed with single-voxel MRS techniques, which obtain MR spectra from one region at a time. MRS imaging (MRSI) obtains MR spectra from many regions simultaneously. Studies using single-voxel (19,20) and MRSI techniques (21) in our laboratory (19,21) and others (20) have shown that [31P]MRS demonstrates interictal metabolic changes in the tempsral lobe containing the seizure focus as compared with the contralateral temporal lobe (i.e., asymmetry of 31P metabolites). These asymmetries include increased pH (19,21), increased Pi (19,21), decreased PME (19,21), and decreased PCr/Pi (20) in the ipsilateral temporal lobe. Although we previously reported increased pH in the region of the ipsilateral hippocampus (19,21), other investigators did not observe increased pH (20,22). The previous [31P]MRS and [1H]MRSI studies of epilepsy [except one study of frontal lobe epilepsy (23)] have focused on asymmetries in the temporal lobe.

Therefore, our overall goal of this study was to compare the 31P metabolites in different brain regions of TLE patients with those from controls. Our specific aims were first, to determine whether asymmetries of 31P metabolites (especially pH, Pi, and PME) could be detected in normal subjects; second, to determine the extent to which 31P asymmetries exist in different brain regions of TLE patients, especially in the hippocampus and the temporal lobe; third, to determine if the 31P asymmetries in TLE are due in part to alterations on the ipsilateral side; and fourth, to determine if 31P abnormalities exist on the contralateral side of TLE patients. A preliminary account of our study was reported as an abstract (24).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All experiments were approved by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Committee on Human Research and informed consent was obtained prior to the study of each patient. Control subjects (n = 10) without personal or family history of epilepsy or other neurologic disease were age and sex matched with the TLE patients. Patients (n = 11) with medically refractory unilateral complex partial seizures (CPS) arising from the anterior mesial temporal regions were studied; 31P data obtained from the hippocampal region of 7 of these subjects (demonstrating increased pH, increased Pi, and decreased PME relative to the contralateral side) were previously reported (21); however, in the previous study no regions outside the hippocampus were examined. Demographic patient data are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the patients was 32.5 years (range 9−41 years) and mean duration of the seizures was 20.7 years (range 3−34 years). All patients were being considered for temporal lobectomy to treat their refractory seizure disorder. Seizure localization and laterality were documented by interictal and ictal recordings on EEG/video-telemetry (VEEG). SPECT, MRI and, occasionally, PET scans were also performed. Patients demonstrating focal abnormalities on MRI that suggested neoplastic or vascular pathologies were excluded. In all patients, the seizures arose from the medial temporal region, documented by interictal and ictal recordings on scalp and, as necessary, subdural VEEG. For determination of seizure location, the recordings of a minimum of four seizures were obtained, with localized onsets consisting of either voltage attenuation or rhythmic spikes that began with or preceded the clinical onsets. All patients demonstrated exclusively unilateral seizure onsets and unilateral discharge predominance interictally. All patients reported that they had been seizure-free for at least 48 h before the MRSI study, and no patient reported an ictal event during the study.

TABLE 1.

Demographic data of patients with focal epilepsy

| Patient/age (yr)/sex | Duration (yr) | Etiology | Focus | MRI | SPECT | Pathology | Surgical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/35/F | 30 | Unknown | LT | ↑ Signal L H | ND | ND | ND |

| 2/37/F | 9 | Unknown | LT | ↑ Signal L H | ND | Ganglioglioma | ↓ 90% |

| 3/20/M | 19 | Birth injury? | RT | Atrophy R H | ↓ Perf RT | MTS | Seizure-free |

| 4/22/M | 19 | Birth injury? | RT | ↑ Signal RT | ↑ Perf RT | Ganglioglioma | Seizure-free |

| 5/19/M | 18 | Birth injury, febrile? | LT | Atrophy R H | ↓ Perf LT | MTS | Seizure-free |

| 6/41/M | 3 | Unknown | RT | WNL | WNL | MTS | Seizure-free |

| 7/40/F | 28 | Unknown | RT | WNL | WNL | MTS | ↓ 75% |

| 8/36/M | 26 | Unknown | LT | ↑ Signal L H | WNL | MTS | No change |

| 9/34/M | 22 | Unknown | RT | ↑ Signal L H | ND | ND | ND |

| 10/35/F | 34 | Birth injury? | LT | Atrophy L H | ND | MTS | Seizure-free |

| 11/39/F | 20 | Unknown | RT | ↑ Signal RT | ND | MTS | Seizure-free |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; T, temporal lobe; H, hippocampal region; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; Perf, perfusion measured by [99Tc]HMPAO SPECT; WNL, within normal limits; MTS, mesial temporal sclerosis.

Nine of the 11 patients underwent seizure surgery (pathology and surgical outcomes shown in Table 1). All the brains appeared grossly normal at surgery, but the mesial temporal structures were firm to suction. Seven of the 9 patients who underwent seizure surgery had findings consistent with MTS, including increased astrocytes and decreased neurons in the dentate gyrus and Ammon's horn. In addition to features consistent with MTS, two patients had small unsuspected gangliogliomas which were resected. The finding of gangliogliomas in 2 of our patients was highly unusual and are the only such cases in our surgical series of >150 temporal lobectomies.

MRI acquisition

MRI and MRSI studies were performed on a Gyroscan S15 whole-body system (Philips Medical Systems, Shelton, CT, U.S.A.) operating at 2 T. Before MRSI was performed, regular MRI scans were obtained. A sagittal scout (using fast field echo) slice was obtained to ensure that the brain was in the center of the head coil; then 16 T1-weighted sagittal scout slices (7.1 mm thick, 0.7 mm gap, TR = 500 ms, TE = 30 ms) and 16 T2-weighted transaxial slices (7.1 mm thick, 1.4 mm gap, TR = 2,500 ms, TE = 30 and 80 ms) were obtained. The transaxial slices were angulated 10°−-30° supraorbitally beyond the orbital-auditory meatal (OAM) plane as observed on the sagittal locator slices. Because these MRI studies were performed several years ago, they are not optimal by today's standards.

MRSI acquisition

After MRI was performed, the B0 magnetic field was shimmed (nonlocalized) with the MRI coil and the subject was then removed from the magnet while the 31P coil was placed. For accurate repositioning of the subject's head, a vacuum-assisted head-holder, padded straps, and fiducial markings (forehead and temple on paper tape) were used. For [31P]MRSI, the equipment and acquisition parameters described by Hugg et al. (21) were used: birdcage 31P head coil, repetition time 350 ms, partial tip angle 34°, and effective encoding 12 × 12 × 12 phase encoding steps over a field of view of 270 × 270 × 270 mm. This resulted in a nominal voxel size of 11.4 cm3. The angulation of the [31P]MRSI was identical to the preceding MRI. With eight phase-cycled acquisitions, the total acquisition time was 43 min.

MRSI processing

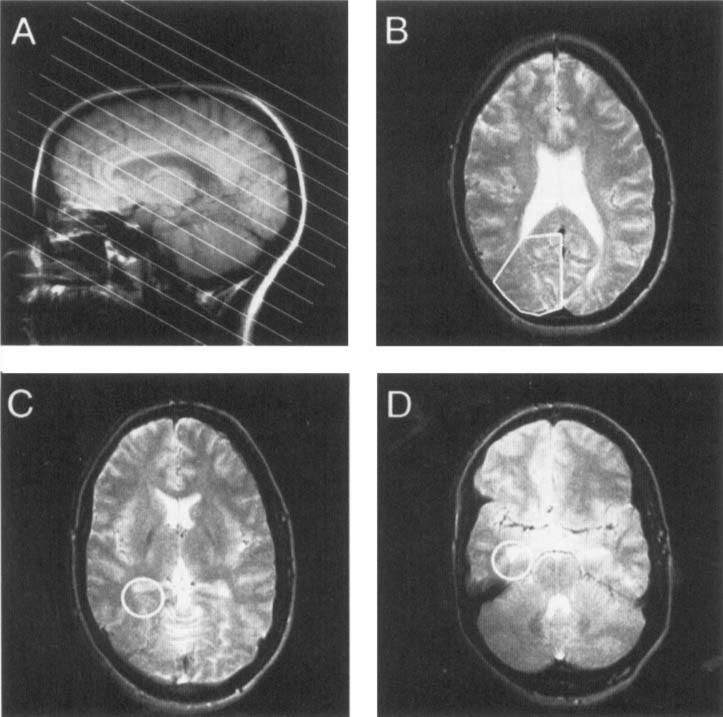

All data processing was performed by an operator completely blinded to diagnosis (i.e., TLE vs. control) and side of focus. MRSI scans were reconstructed using Fourier transforms with apodization and zero-filling to 32 × 32 interpolated voxels in 16 interpolated transaxial planes. The nominal MRSI thickness corresponded to two MRI slices (Fig. 1). After zero-filling and mild Gaussian smoothing applied during reconstruction, the effective voxel size was ∼25 cm3. The MRSI scans were interpolated to 64 × 64 voxels for simultaneous display with coregistered MRI scans so that MRS voxels could be selected from the desired location, guided by the MRI display (25). Voxel selection from the regions of interest was performed “blind,” without knowledge of the focus, using the T2-weighted MRI slices. Data analysis and voxel/region selection were performed in an identical manner (same position, same size) for patients and volunteers. Each region was outlined by hand on the appropriate MRI slices, and spectra were selected with the MRI as a guide and with home-written spectroscopic imaging software (SID) (24,26). For data analysis, voxels centered on the following regions were selected from each side in the brain (Fig. 1). The voxels are named according to the region on which they were centered. The large voxel size resulted in other structures being included within each voxel, and in some cases there was substantial overlap between adjacent voxels, especially in the hippocampal region: anterior hippocampus (AH), entire hippocampus (H), posterior hippocampus (PH), a region of temporal neocortex lateral to the hippocampus (LT), temporal lobe (T), frontal lobe (F) occipital lobe (O), and parietal lobe (P). For the H, T, F, O, and P regions, spectra were summed from voxels covering the entire region. For AH, PH, and LT regions, spectra from single voxel selection were used (effective voxel size of 25 cm3). Because the entire hippocampus is ∼3 cm3, there is substantial overlap of tissue between the AH and PH voxels. The individual (single voxel) and summed regions were selected as follows: The anterior hippocampus was selected on the most inferior slice that demonstrated the anterior temporal horn. The total hippocampus (summed region ∼40 cm3) was a multislice region and was selected from the AH through the PH and including the midhippocampal volumes between these two regions. This 40-ml region surrounds the hippocampus, and only a small portion is filled with the hippocampus. The posterior hippocampus and the lateral temporal region were selected from the slice that showed the lower part of the atrium of the lateral ventricle. The point halfway between the lateral ventricle wall and the lateral temporal cortex was chosen as the center of the lateral temporal lobe volume. The total temporal lobe (summed region ∼80 cm3) was a multislice summed volume region with its boundaries defined by the cerebellum and the lateral sulcus (sylvian fissure) and in the lower slices the suprasellar region and in the higher slices the midbrain and the thalamus. The frontal lobe region (summed region ∼100 cm3) was a multislice region chosen from the MRI slices starting one slice below the lateral ventricle through all higher slices. The entire region anterior of the central sulcus was selected. The occipital region (summed region ∼40 cm3) was chosen from the MRI slice that showed the occipital horn most clearly. The summed volumes were bounded by the parietooccipital sulcus. The parietal region (summed region ∼45 cm3) was a multislice region starting from one MRI slice above the lateral ventricle through all higher slices. The entire region posterior to the post central sulcus was selected. However, since the angulation beyond the OAM plane was not always the same in all patients and volunteers, in some cases the actual region selected differed slightly from this description. Because the spatial resolution was 25 cm3, the indicated single voxel regions are approximations of the identified structure. Therefore, the single voxel containing, e.g., the AH, also contains signal from outside the AH. Therefore, because of the coarse spatial resolution, conclusions about localization of a focus in the temporal lobe at a level finer than medial or lateral cannot be robust.

FIG. 1.

Example of region selection in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. A: Saggital scout magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan shows the position of the 12 [31P]MR spectroscopy imaging ([31P]MRSI) slices (slice thickness 17 mm) obtained from the three-dimensional [31P]MRSI. Each MRSI slice corresponds to two MRI slices. B–D: Examples of selection of the occipital lobe (summed volumes), posterior hippocampus, and anterior hippocampus, respectively, using spectroscopic imaging (SID) software.

Data processing

For each spectrum corresponding to one of the above-described regions on each side of the brain, seven 31P peaks were identified for fitting by the NMRl program (Tripos): PME, Pi, PDE, PCr, and the three phosphate peaks of adenosine triphosphate (α, β and γ ATP). Intracellular pH was calculated from the curve-fitted chemical shift of Pi referenced to PCr = 0 ppm (27). 31P Metabolic data are expressed in two ways: First, all metabolite data were calculated as percentage of total 31P metabolites. For control subjects “left/right” metabolite ratios were determined. Finally, for each region of TLE patients and controls, the asymmetry index “A” (21) for each selected region was calculated by: A = ([Pi]/([H+][PME]) (ipsilateral))/([Pi]/([H+][PME]) (contralateral)).

Statistical analysis

Graphical tests for normality and heteroscedasticity (unequal variance) were performed (28). (Pi) and (PME) were log-transformed before we performed the statistical tests to correct for nonnormality and heteroscedasticity of the data (pH was not log-transformed since it is the logarithm of H+). To establish that no systematic asymmetries in metabolites between hemispheres were present in normal subjects, we tested the 10 controls for significant differences in (Pi), pH, and (PME) between the left and right sides of the AH by paired t tests; the entire temporal lobe simultaneously using measurements from AH, PH, and lateral temporal lobe and multivariate repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); and the whole brain, simultaneously using repeated measurements from the temporal, frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes with multivariate repeated-measures ANOVA.

Multivariate repeated-measures ANOVAs were first used to determine if there were significantly differences between TLE patients and controls and between ipsilateral and contralateral sides of TLE patients. Subsequently, t tests were used to determine significance for specific regions. The t test results are shown in Table 2. All statistics were corrected for multiple comparisons. Three distinct comparisons were made between patients and controls: (a) between AHs, using Welch's form of the t test; (b) between repeated measurements from the temporal lobe (AH, H, PH, and lateral temporal lobe), using multivariate repeated-measures ANOVA and (c) between repeated measurements from the whole brain (temporal, frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes), using multivariate repeated-measures ANOVA. Comparisons (b) and (c) were made in a single multivariate repeated-measures ANOVA, with contrast analysis (29) used to make the focused comparisons. Finally, to determine if the magnitude of asymmetries between ipsilateral and contralateral (Pi), pH, and (PME) were inversely related to distance from the epileptogenic seizure focus (the AH), linear contrasts in a multivariate repeated-measures ANOVA were used.

TABLE 2.

Relative concentrations of pH, Pi, and PME in ipsilateral and contralateral side of 11 patients with TLE and 10 normal control subjects

| Region | pH | Pi | PME |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH Contralateral TLE | 6.97 ± 0.03 | 0.068 ± 0.013 | 0.212 ± 0.017 |

| AH Ipsilateral TLE | 7.13 ± 0.04a,b | 0.121 ± 0.011c,d | 0.151 ± 0.012c,d |

| AH Normal controls | 7.02 ± 0.03 | 0.074 ± 0.009 | 0.203 ± 0.012 |

| H Contralateral TLE | 7.01 ± 0.02 | 0.046 ± 0.007 | 0.211 ± 0.016 |

| H Ipsilateral TLE | 7.07 ± 0.04 | 0.094 ± 0.006c | 0.167 ± 0.012e |

| H Normal controls | 7.03 ± 0.02 | 0.066 ± 0.008 | 0.187 ± 0.016 |

| PH Contralateral TLE | 7.00 ± 0.04 | 0.060 ± 0.007 | 0.192 ± 0.015 |

| PH Ipsilateral TLE | 7.05 ± 0.03 | 0.101 ± 0.015c | 0.142 ± 0.014b,e |

| PH Normal controls | 7.03 ± 0.03 | 0.072 ± 0.007 | 0.180 ± 0.011 |

| LT Contralateral TLE | 7.00 ± 0.02 | 0.075 ± 0.011 | 0.194 ± 0.016 |

| LT Ipsilateral TLE | 7.02 ± 0.04 | 0.107 ± 0.010 | 0.141 ± 0.014b,e |

| LT Normal controls | 7.02 ± 0.04 | 0.072 ± 0.008 | 0.196 ± 0.012 |

| T Contralateral TLE | 6.96 ± 0.02d | 0.056 ± 0.008 | 0.245 ± 0.024d |

| T Ipsilateral TLE | 7.05 ± 0.04e | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 0.145 ± 0.015c |

| T Normal controls | 7.03 ± 0.02 | 0.074 ± 0.006 | 0.183 ± 0.012 |

| F Contralateral TLE | 6.99 ± 0.01 | 0.045 ± 0.008 | 0.218 ± 0.017 |

| F Ipsilateral TLE | 7.00 ± 0.01 | 0.055 ± 0.011 | 0.217 ± 0.021 |

| F Normal controls | 7.03 ± 0.02 | 0.059 ± 0.006 | 0.208 ± 0.016 |

| O Contralateral TLE | 6.97 ± 0.02 | 0.065 ± 0.013 | 0.217 ± 0.014 |

| O Ipsilateral TLE | 7.03 ± 0.03 | 0.068 ± 0.010 | 0.181 ± 0.017 |

| O Normal controls | 7.04 ± 0.02 | 0.072 ± 0.007 | 0.167 ± 0.011 |

| P Contralateral TLE | 6.99 ± 0.03 | 0.067 ± 0.013 | 0.192 ± 0.017 |

| P Ipsilateral TLE | 7.03 ± 0.04 | 0.052 ± 0.006 | 0.199 ± 0.015 |

| P Normal controls | 7.01 ± 0.02 | 0.052 ± 0.008 | 0.194 ± 0.013 |

Pi, inorganic phosphate; PME, phosphomonoesters; TLE, temporal lobe epilepsy; AH, anterior hippocampus; PH, posterior hippocampus; H, entire hippocampus; LT, lateral temporal to the hippocampus; T, entire temporal lobe; F, frontal lobe; O, occipital hippocampus. Pi and PME are expressed as a fraction of total 31P.

Values are mean ± SE.

p < 0.01, ipsilateral versus contralateral side of focus, two-tailed Student's t test.

p < 0.05, ipsilateral and contralateral AH of TLE patients versus those of controls.

p < 0.005, ipsilateral versus contralateral side of focus, two-tailed Student's t test.

p < 0.01, ipsilateral and contralateral AH of TLE patients versus those of controls.

p < 0.05 ipsilateral versus contralateral side of focus, two-tailed Student's t test.

RESULTS

31P Metabolites in brains of controls

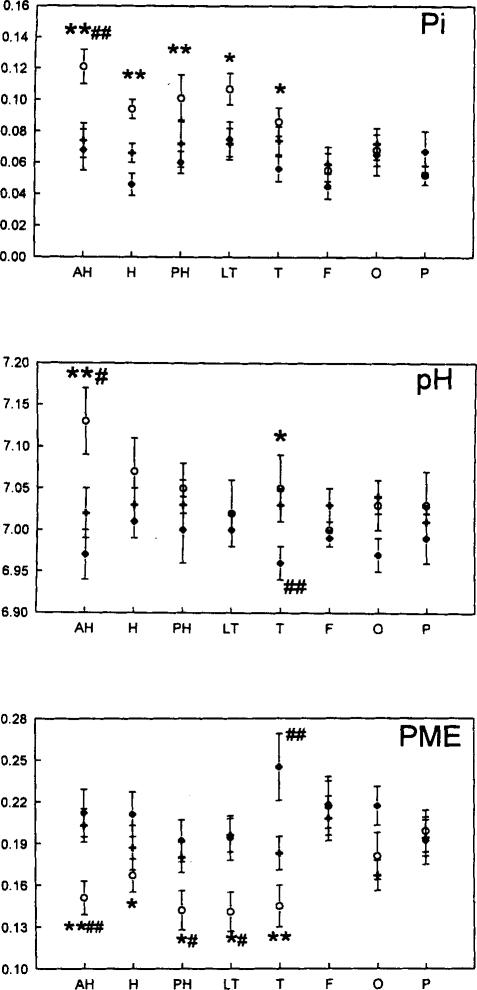

Table 2 and Fig. 2 demonstrate (Pi), pH, and (PME) data obtained from the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the eight regions of TLE patients and from the same eight regions of controls. There were no systematic differences in (Pi), pH, (PME), or any other 31P metabolite between the right and left sides of the eight regions of controls. Therefore, for comparisons of ipsilateral and contralateral sides of TLE patients with control data, data from the right and left sides of each of the eight control regions were combined.

FIG. 2.

Values of inorganic phosphate (Pi) (top), pH (middle), and phosphomonoesters (PME) (bottom) for ipsilateral (open circles), contralateral (solid circles), and controls (open triangles). Pi and PME are expressed as fraction of total 31P signal integral. AH, anterior hippocampus; H, hippocampus, PH, posterior hippocampus; LT, lateral temporal lobe; T, temporal lobe; F, frontal lobe; O, occipital lobe; P, parietal lobe. Significant differences between ipsilateral, contralateral, and control are described in the text.

Comparison between ipsilateral and contralateral sides of TLE patients

Figure 2 shows asymmetries of pH, (Pi), and (PME) in the temporal lobe, and Table 2 indicates significant differences between ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the eight regions. There were no significant asymmetries for the other metabolic data. (Pi) was significantly greater and (PME) was significantly less in the ipsilateral as compared with the contralateral sides of all regions in the temporal lobe and in the entire temporal lobe. The pH was significantly higher in the ipsilateral anterior hippo-campus and in the summed temporal lobe as compared with the contralateral side. For all of these, there was no statistically significant relationship between metabolites and distance from the AH (presumably the seizure focus). No metabolites showed significant differences between ipsilateral and contralateral regions outside the temporal lobe.

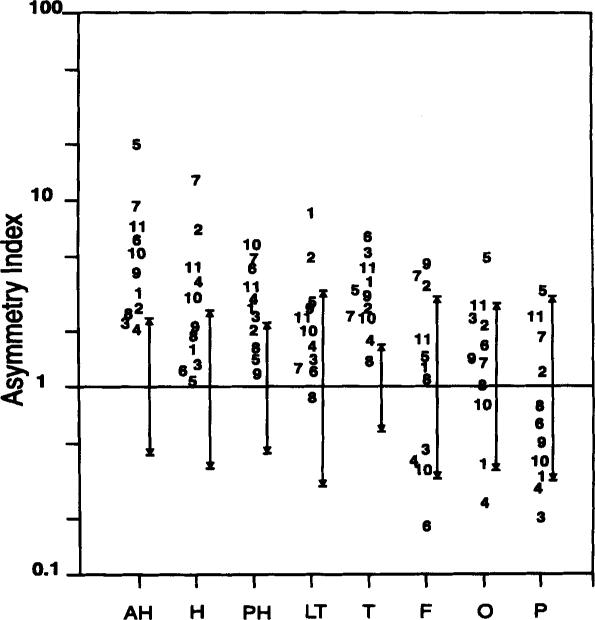

Asymmetry scores and localization of the seizure focus

Figure 3 shows the asymmetry index (A) for all regions; each number in the figure refers to 1 patient. The spread bars to the immediate right of the individual patient numbers indicate the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each region as calculated from the control subjects. Figure 3 shows that the TLE patients have greater metabolic asymmetry (defined by the asymmetry index) than controls for the AH (p < 0.001) and entire temporal lobe (p < 0.001); the hippocampus (p < 0.01), PH (p < 0.01), and lateral temporal lobe regions (p < 0.05) of the TLE patients showed significant asymmetry, but there was no significant asymmetry for regions outside the temporal lobe (frontal, occipital, and parietal lobe). Furthermore, identification of the region of the brain with the greatest asymmetry may provide information concerning the location of the seizure focus (i.e., the hippocampus in TLE); therefore, the regions of greatest asymmetry were identified. When data from AH and PH were compared, the AH had greater asymmetry in 8 of 11 cases (Fig. 3). When all regions within the temporal lobe were compared, the AH had the greatest asymmetry in 6 of 11 cases. When regions of the whole brain were compared, the AH had the greatest asymmetry in 5 of 11 cases.

FIG. 3.

The individual asymmetry index ([Pi]/ [H+][PME] ipsilateral/[Pi]/[H+][PME] contralateral) for each region. Each number represents 1 patient with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). The largest asymmetry index for each patient is circled. The bars to the immediate right of the individual patient numbers indicate the 95% confidence intervals for each region calculated from the control subjects. Pi, inorganic phosphate; PME, phosphornonoesters; AH, anterior hippocampus; H, hippocampus; PH, posterior hippocampus; LT, lateral temporal from the hippocampus; T, entire temporal lobe; F, entire frontal lobe; O, entire occipital lobe; P, entire parietal lobe.

Comparison between ipsilateral side of TLE patients and controls

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show differences between ipsilatera1 and contralateral metabolites of TLE patients and control values (mean of right and left sides shown in Fig. 2) for all eight regions. In the AH, ipsilateral (Pi) was greater (p < 0.01), pH was higher (p = 0.02), and (PME) was less (p = 0.01) than control values. Across the entire temporal lobe, there were statistically significant differences for increased ipsilateral (Pi) (p < 0.01) and decreased (PME) (p < 0.01), but not for pH, as compared with controls. These results clearly demonstrate that ipsilateral pH and (Pi) are increased and (PME) is decreased in TLE patients as compared with control values, suggesting that the asymmetry between ipsilateral and contralateral sides of TLE patients is largely due to changes on the side of the seizure focus.

Comparison between contralateral side of TLE patients and controls

Table 2 and Fig. 2 also show significant differences between 31P metabolites on the contralateral side of TLE patients and those of controls. These changes were smaller than those on the ipsilateral side and were not statistically significant in the AH or across the temporal lobe, However, ANOVA showed significantly decreased pH (p = 0.01) and increased (PME) (p < 0.01) in the contralateral hemisphere (including temporal, frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes) in TLE patients as compared with controls. Therefore, these results demonstrate 31P changes on the contralateral side that are opposite to those observed on the ipsilateral side and suggest that the asymmetries in TLE patients are in part due to diffuse changes on the contralateral side.

DISCUSSION

Our data show first that there were no asymmetries of (Pi), pH, or (PME) between regions in the left and right hemispheres of normal controls; second, in TLE, (Pi) and pH were higher and (PME) was lower throughout the entire ipsilateral temporal lobe as compared with the contralateral side, and there were no significant asymmetries outside the temporal lobe; third, for all three metabolites, the degree of ipsilateral/contralateral asymmetry (i.e., asymmetry index) was substantially greater for the temporal lobe than for the frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes, and these asymmetries provide additional data for seizure localization; fourth (Pi) and pH were increased and (PME) was decreased on the ipsilateral side of TLE patients as compared with controls; and fifth, there were changes in (Pi), pH and (PME) on the contralateral side of TLE patients as compared with controls, in direct contrast to the changes on the ipsilateral side. Together, findings demonstrate metabolic changes that occur in the brains of TLE patients and may prove useful adjuncts for seizure focus lateralization.

We noted no asymmetries in (Pi), pH, or (PME) in normal subjects, thus establishing the validity of the asymmetries observed in TLE patients. (Pi) and pH were higher and (PME) was lower throughout the entire ipsilateral temporal lobe of TLE patients as compared with the contralateral side, and there were no significant asymmetries outside the temporal lobe. This new finding adds to the previous reports in studies in which single-volume techniques (19,20) were used to detect asymmetries in the temporal lobe. The finding that these metabolite changes occur throughout the temporal lobe indicates that these changes involve more than just the epileptogenic region and are occurring outside the seizure focus. This result is analogous to findings with PET in TLE of hypometabolism throughout the temporal lobe (13). Because the ipsilateral temporal lobe is more involved during seizures than are other brain regions, this finding is consistent with metabolite changes being the result of seizure activity. Alternatively, these changes (especially increased pH) might be responsible in part for increased seizure activity arising from the temporal lobe (described below).

For all three metabolites, the degree of ipsilateral/contralateral asymmetry (i.e., asymmetry index) was substantially greater for the temporal lobe than for the frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes. Furthermore, the asymmetry index is influenced by contributions from all three metabolites (Pi, pH, PME). The asymmetry index A localized the focus to the hippocampus in 9 of 11 cases. The combining of metabolite values into an asymmetry index provides additional data for seizure lateralization. Again this result demonstrates the value of MRSI as compared with single-volume techniques. The significance of this finding is that [31P]MRSI data may be useful for lobar localization of the seizure focus, but the failure to detect a trend within the temporal lobe suggests that [31P]MRS alone will not be very successful in localizing the seizure focus in subregions of the temporal lobe unless image resolution can be increased. The clinical usefulness of this approach will ultimately be determined if [31P]MRSI provides independent information for prediction of surgical outcome; results of a similar approach using [1H]MRSI have been reported by our laboratory (30).

The fourth major finding of this study was that (Pi) and pH were increased and (PME) was decreased on the ipsilateral side in TLE compared to controls. In previous [31P]MRS studies, investigators detected significant asymmetries in (Pi), pH, and (PME) between ipsilateral and contralateral sides. Hugg et al. (21) demonstrated such asymmetries for the AH. Kuziecky et al. (20) reported asymmetries of PCr and Pi, but not of pH. However, these investigators did not include normal controls and therefore could not determine whether the metabolic abnormalities were confined to the ipsilateral side, were present on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides, or were confined to the contralateral side (although the latter was less likely, since PET and SPECT had detected metabolic abnormalities on the ipsilateral side). Although we had considered it likely that [31P]MRS would detect abnormal (Pi), pH, and (PME) on the ipsilateral side of TLE patients as compared with controls, this possibility had not been demonstrated previously.

Recently, at the University of Alabama, Chu et al. (22) reported a [31P]MRS study at 4.1-T that showed no increase in pH in the ipsilateral temporal lobe as compared with the contralateral side in TLE patients or with that in normal controls. We acknowledge that these studies, performed at higher magnetic field, have spectral quality superior to and voxel sizes than those used in the present study. We do not know why we have observed pH differences in different patient populations and with different methods (ISIS and MRSI) while the group at the University of Alabama has not replicated these findings; a different patient population and different treatments may explain the discrepancy in findings.

Changes in (Pi), pH, and (PME) in the opposite direction on the contralateral side of patients as compared with controls was unexpected ANOVA detected statistical changes in (Pi), pH, and (PME) on the contralateral side of TLE patients as compared with controls in direct contrast to the changes on the ipsilateral side. The mechanism of metabolite changes in the contralateral side of TLE patients can only be speculated on, but these changes may in some way be a response to repeated seizure activity initiated on the other side of the brain. Assuming that these results are replicated, they suggest that metabolic changes in TLE are greatest near the seizure focus and also produce diffuse changes throughout the contralateral hemisphere. These contralateral changes may also be useful for seizure focus localization.

Our results provide no direct insight into the biological mechanisms responsible for the metabolic changes on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of epileptic brains. However, there are two major possible explanations: The metabolic changes in TLE may be related to the causation of seizures, or these changes may be the result of seizures or the medications used for therapy. A medication effect appears unlikely, because the patients were treated with a variety of different medications and the changes were different on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides and in different brain regions. The elevated pH in the seizure focus was previously suggested (19,21) to be involved in the causation of seizures, since alkalosis reduces seizure threshold. Alternatively, repeated seizures (which produce acidosis) might induce adaptive changes in buffering systems such as upregulation of the Na+/H+ antiporter, leading to intracellular alkalosis. These changes could also be due to the pathology of MTS, increased astrocytes, and decreased neuronal density. Although pH is increased in glial tumors (31) and in infarcted regions where glial cells have replaced neurons (32-34), astrocytes have not been characterized by significantly increased pH, increased Pi, and decreased PME. Although hippocampal atrophy was detected in 3 patients, none of the patients showed significantly dilated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces. The pH of CSF is higher than that of normal brain tissue, but the phosphate concentration of CSF is low (0.2 mM) (35) and below current in vivo MR delectability. Therefore, it is unlikely that dilated CSF spaces, caused by hippocampal atrophy, are responsible for the observed metabolite changes. Animal models have shown acidosis in the brain during the ictus (36-39), whereas postictal pH slowly normalized and even became alkalotic. The metabolic changes in the contralateral brain of persons with epilepsy are most likely the result of seizure activity, since both hemispheres are involved in patients with CPS. In addition, acidosis in the contralateral brain would tend to increase the seizure threshold and thus may be an adaptive mechanism. Future MRSI studies of human epilepsy and animal models of epilepsy may provide greater insight into the mechanisms of these metabolic alterations.

Study limitations

Although in our study the changes measured in TLE patients were statistically significant, their magnitude was relatively small. One limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size, and our results should be verified with larger numbers of TLE patients and controls. A second limitation is that only patients with TLE were studied. Future studies should include patients with different types of epilepsy to determine whether the regional patterns detected in the present study are characteristic of TLE only or occur in other epilepsies. A third limitation is that because the present study was performed several years ago, the MRI scans are not optimal by today's standards. Finally, [31P]MRSI is limited by coarse spatial resolution as compared with MRI or [1H]MRSI and by long acquisition times. Because of the coarse spatial resolution, conclusions about localization of a focus in the temporal lobe at a level finer than medial or lateral cannot be robust. Notwithstanding these limitations of [31P]MRSI, the information on metabolite asymmetry it provides may prove useful when added to other clinical and neuroimaging information. Further studies in which [31P]MRSI and other data are compared with clinical outcome will be necessary to determine the practical value of [31P]MRSI measurements.

TABLE 3.

Left to right symmetry of 31P metabolites in control subjects

| Region | pH | Pi | PME |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH | 1.001 ± 0.015 (0.986−1.012) | 1.041 ± 0.532 (0.660−1.421) | 0.985 ± 0.178 (0.858−1.112) |

| H | 0.998 ± 0.009 (0.990−1.011) | 1.095 ± 0.513 (0.727−1.462) | 0.955 ± 0.210 (0.805−1.104) |

| PH | 0.995 ± 0.015 (0.984−1.009) | 0.997 ± 0.416 (0.699−1.295) | 1.038 ± 0.178 (0.911−1.166) |

| LT | 0.994 ± 0.032 (0.972−1.017) | 0.978 ± 0.338 (0.737−1.222) | 1.024 ± 0.280 (0.844−1.205) |

| T | 1.004 ± 0.010 (0.996−1.010) | 0.972 ± 0.315 (0.746−1.197) | 1.032 ± 0.319 (0.804−1.261) |

| F | 1.003 ± 0.016 (0.992−1.014) | 1.046 ± 0.145 (0.723−1.470) | 0.917 ± 0.300 (0.703−1.135) |

| O | 1.001 ± 0.008 (0.993−1.010) | 1.061 ± 0.612 (0.619−1.501) | 0.983 ± 0.298 (0.797−1.229) |

| P | 0.999 ± 0.009 (0.991−1.009) | 1.096 ± 0.802 (0.523−1.671) | 1.013 ± 0.302 (0.824−1.243) |

Abbreviations as in Table 2.

Data are mean ± SE (95% confidence interval).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) Grants No. 900-574-202 and 900-537-063 (J.v.d.G.), NIH Grant No. R01-AG10897 (M.W.W.), NIH Grant No. R01-NS31966 (K.L.), Philips Medical Systems, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service (M.W.W.).

Footnotes

Dr. Hugg's present address is Department of Neurology, Center for Nuclear Imaging Research, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, U.S.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scheuer ML, Pedley TA. The evaluation and treatment of seizures. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1468–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011223232107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babb TL, Brown WJ. Pathological findings in epilepsy. In: Engel J Jr, editor. Surgical treatment of the epilepsies. Raven Press; New York: 1987. pp. 511–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GD, Berkovic SF, Tress BM, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis can be reliably detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1990;40:1869–75. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.12.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkovich SF, Andermann F, Ethier R, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:175–82. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinz ER, Crain BJ, Radtke RA, et al. MR Imaging in patients with temporal lobe seizures: correlation of results with pathologic findings. AJR. 1990;155:581–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.3.2117360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinz ER, Heinz TR, Radtke RA, et al. Efficacy of MR vs CT in epilepsy. AJR. 1989;152:347–52. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theodore WH, Katz D, Kufta C, et al. Pathology of temporal lobe foci: correlation with CT, MRI and PET. Neurology. 1990;40:797–803. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schörner W, Meencke HJ, Felix R. Temporal lobe epilepsy: comparison of CT and MR imaging. AJNR. 1987;8:773–81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia PA, Laxer KD, Barboro MM, Dillon WP. The prognostic value of qualitative MRI hippocampal abnormalities in patients undergoing temporal lobectomy for medically refractive seizures. Epilepsia. 1994;35:520–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laxer KD, Garcia PA. Imaging criteria to identify the epileptic focus. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1993;4:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryvlin P, Philippon B, Cinotti L, et al. Functional neuroimaging strategy in temporal lobe epilepsy: a comparative study of 18FDGPET and 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:650–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theodore WH, Brooks R, Sato S, et al. The role of PET in the evaluation of seizure disorders. Ann Neurol. 1984;15(suppl):S176–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry TR, Maziotta JC, Engel J., Jr Quantifying interictal metabolic activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:748–57. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowe CC, Berkovic SF, Austin M, et al. Postictal SPECT in epilepsy. Lancet. 1989;18:389–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryding E, Rosen I, Elmqvist D, Ingvar DH. SPECT measurements with 99m Tc-HM-PA0 in focal epilepsy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:S95–100. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams C, Hwang PA, Gilday Dl, et al. Comparison of SPECT, EEG, CT, MRI and pathology in partial epilepsy. Pedriatr Neurol. 1992;8:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(92)90028-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefan H, Bauer J, Feistel H, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow during focal seizures of temporal and frontocentral onset. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:162–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matson GB, Weiner MW. Spectroscopy. In: Stark DD, Bradley WG Jr, editors. Magnetic resonance imaging. 1st ed. Mosby-Year Book; St. Louis: 1998. p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laxer KD, Hubesch B, Sappey-Marinier D, Weiner MW. Increased pH and inorganic phosphate in temporal seizure foci, demonstrated by 31P MRS. Epilepsia. 1992;33:618–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzniecky R, Elgavish GA, Hetherington HP, et al. In vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1992;42:1586–90. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.8.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugg JW, Laxer KD, Matson GB, et al. Lateralization of human focal epilepsy by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Neurology. 1992;42:2011–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.10.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu WJ, Hetherington HP, Kuzniecky RI, et al. Is the intracellular pH different from normal in the epileptic focus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy? Neurology. 1996;47:756–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia PA, Laxer KD, Van der Grond J, Hugg JW, Matson GB, Weiner MW. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:217–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Grond J, Laxer KD, Gerson JR, Hugg JW, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Regional distribution of 31P metabolic changes in temporal lobe epilepsy [Abstract].. Presented at the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; New York. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maudsley AA, Matson GB, Hugg JW, Weiner MW. Display of metabolic information by MR spectroscopic imaging. SPIE. 1993;1887:282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maudsley AA, Lin E, Weiner MW. Spectroscopic imaging display and analysis. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10:471–85. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90520-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petroff OAC, Prichard JW, Behar KL, et al. Cerebral intracellular pH by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurology. 1985;35:7814. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkinson AC. Plots, transformations, and regression. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Contrast analysis: focused comparisons in the analysis of variance. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermathen P, Ende G, Laxer KD, Knowlton RC, Weiner MW. Hippocampal NAA in neocortical epilepsy and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hubesch B, Sappey-Marinier D, Roth K, et al. P-31 MR spectroscopy of normal human brain and brain tumors. Radiology. 1990;174:401–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.2.2296651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hugg JW, Matson GB, Twieg DB, et al. 31 Phosphorus MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) of normal and pathological human brains. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10:22743. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90483-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sappey-Marinier D, Hubesch B, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Decreased phosphorus metabolites and alkalosis in chronic cerebral infarction. Radiology. 1992;182:29–34. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hugg JW, Duijn JH, Matson GB, et al. Elevated lactate and alkalosis in chronic human brain infarction observed by 1H and 31P MR spectroscopic imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:734–44. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siege1 GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Molinoff P. Basic neuro-chemistry. Raven Press; New York: 1989. p. 599. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnall MD, Yoshizaki K, Chance B, Leigh JS. Triple nuclear NMR studies of cerebral metabolism during gene1ized seizur. Magn Reson Med. 1988;6:15–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Younkin DP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Maris J, et al. Cerebral metabolic effects of neonatal seizures measured with in vivo 31P NMR spectroscopy. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:513–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young RS, Osbakken MD, Briggs RW, et al. 31P NMR study of cerebral metabolism during prolonged seizures in the neonatal dog. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:14–20. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siesjö BK, von Hanwehr R, Nergelius G, et al. Extra- and intracellular pH in the brain during seizures and in the recovery period following arrest of seizure activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:47–57. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]