Abstract

Electrochemical immunosensors based on single wall nanotube (SWNT) forests and 5 nm glutathione-protected gold nanoparticles (GSH-AuNP) were developed and compared for the measurement of human cancer biomarker interleukin-6 (IL-6) in serum. Detection was based on sandwich immunoassays using multiple (14-16) horseradish peroxidase labels conjugated to a secondary antibody. Performance was optimized by effective blocking of non-specific binding (NSB) of the labels using bovine serum albumin. The GSH-AuNP immunosensor gave a detection limit (DL) of 10 pg mL-1 IL-6 (500 amol mL-1) in 10 μL calf serum, which was 3-fold better than 30 pg mL-1 found for the SWNT forest immunosensor for the same assay protocol. The GSH-AuNPs platform also gave a much larger linear dynamic range (20-4000 pg mL-1) than the SWNT system (40-150 pg mL-1), but the SWNTs had 2-fold better sensitivity in the low pg mL-1 range.

Keywords: electrochemical immunosensor, cancer biomarker, carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, protein detection

1. Introduction

Sensitive detection of multiple biomarker proteins at point-of-care promises to contribute significantly to disease diagnosis [1,2]. Herein, we evaluate two nanoparticle-based electrochemical immunosensor platforms for the detection of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a 20 kDa cancer biomarker protein [3]. Overexpression of IL-6 is associated with various cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [4], and methods for early detection of this disease are desperately needed [5]. Mean serum IL-6 levels of patients with HNSCC are ~20 pg mL-1 or greater compared to 6 pg mL-1 or less in healthy individuals [4]. Serum IL-6 is also elevated in colorectal [6], gastrointestinal [7] and prostate cancers [8].

The classical enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is an important commercial bioanalysis method for proteins with detection limits (DL) as low as 3 pg mL-1 [9-11]. Conventional ELISA has limitations in analysis time, determination of multiple proteins, sample size, and sensitivity in some cases. Newer approaches for sensitive protein biomarker detection include surface plasmon resonance [12,13,14], surface plasmon fluorescence [15], fluoroimmunoassay using nanoparticles [16,17,18,19], capacitance [20] and nano-transistors [21].

Alternatively, high surface area nanoparticle electrodes offer unprecedented opportunities for high sensitivity immunosensors amenable to determination of multiple proteins [21,22-26]. In this paper, we compare single-wall nanotube (SWNT) forest and gold nanoparticle (AuNP) electrodes (Scheme 1) as platforms for electrochemical immunosensors for IL-6. We chose IL-6 because its very low normal concentration, e.g. compared to PSA, presents a more formidable challenge.

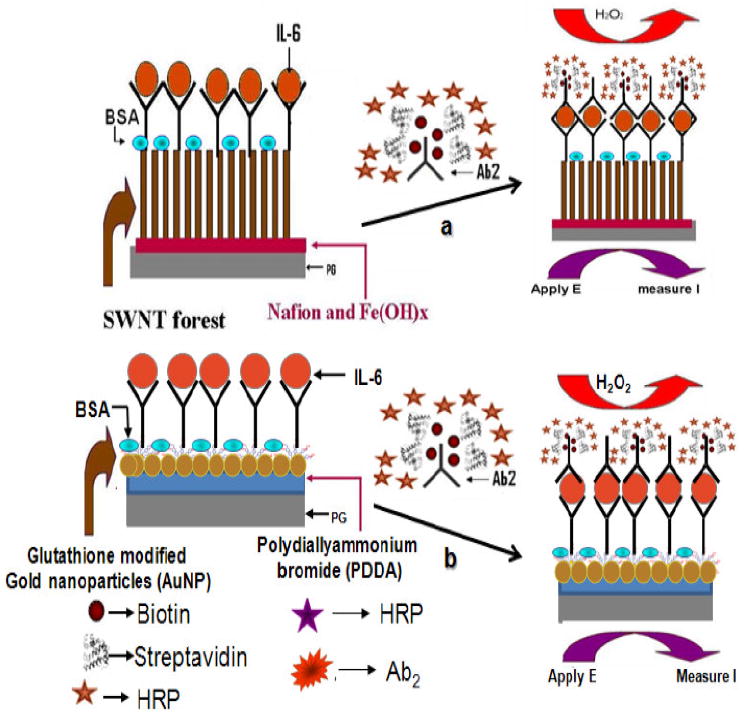

Scheme 1.

Depiction of (a) SWNT immunosensor and (b) AuNP immunosensor platforms after treating with sample and multilabeled Ab2-biotin-streptavidin-HRP14-16. The final detection step involves immersing the fully prepared immunosensor into an electrochemical cell containing PBS buffer and mediator, applying voltage, and injecting a small amount of hydrogen peroxide.

SWNT forests are dense aggregates of nanotube bundles that stand upright on conductive surfaces [27,28]. The AuNP immunosensors feature a dense layer of 5 nm diameter glutathione-protected AuNPs (GSH-AuNPs) on an underlying electrode [26]. Both sensors employ a sandwich assay in which a primary antibody attached to the sensor surface captures the analyte protein from the sample, is washed, and a labeled secondary antibody is added that binds to the protein analyte and is detected by amperometry (Scheme 1). These sensor platforms have both been used for the sensitive and accurate detection of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in serum, but were not compared under identical experimental conditions. Comparison for detection of IL-6 in serum forms the basis of this communication. In both approaches, we utilized biotinylated secondary antibodies (Ab2) bound to streptavidin-HRP, which provided 14 to 16 HRP labels on each Ab2 (Ab2-biotin-streptavidin-HRP14-16). The GSH-AuNP immunosensor gave a 3-fold lower detection limit of 10 pg mL-1 (500 amol mL-1) for IL-6 in 10 μL calf serum compared to the SWNT forest sensor.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

Monoclonal anti-human Interleukin-6 (IL-6) antibody (clone no. 6708), biotinylated anti-human IL-6 antibody, recombinant human IL-6 (carrier-free) in calf serum and Streptavidin-Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were obtained from R&D systems, Inc. HRP (MW 44000 Da), lyophilized 99% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and Tween-20 were from Sigma Aldrich. The immunoreagents were dissolved in pH 7.2 phosphate saline (PBS) buffer (0.01 M phosphate, 0.14 M NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl). 1-(3-(dimethylamino)-propyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHSS) were dissolved in water immediately before use.

2.2. Immunosensor fabrication

All steps were done at ambient temperature (~ 22 °C). SWNT forests were assembled from oxidized SWNT dispersions in DMF on a thin iron oxide-Nafion layer on 0.14 cm2 pyrolytic graphite (PG) disks as reported previously [28], except that the iron oxide underlayer was deposited from 31 mM FeCl3, pH 1.8. The immunosensor featuring a dense layer of 5 nm AuNPs was fabricated on PG disks as described previously [26]. Capture antibody was attached to sensors via amidization by spotting 30 μL of 400 mM EDC/100 mM NHSS onto the nanostructured electrodes, washing 10 min., then incubating for 3 h with 20 μL 0.67 nmol L-1 (100 μg mL-1) primary anti-IL-6 antibody in pH 7.2 buffer. The assembly was washed successively with 0.05 % Tween-20 in buffer and PBS buffer for 3 min each, then incubated for 1 h with 20 μL 1% BSA in buffer, followed by washing with 0.05 % Tween-20 in buffer and PBS buffer for 3 min. These immunosensors were usable for several days when stored at 5 °C.

For detection of IL-6, the immunosensors were incubated 1 h with a 10 μL drop of calf serum containing IL-6, followed by washing with 0.05 % Tween-20 in buffer and PBS buffer for 3 min each. Then, the sensor was incubated with 10 μL of 1.1 pmol L-1 biotinylated secondary antibody (Ab2) for 1 h, followed by washing with 0.05 % Tween-20 in buffer and PBS buffer for 3 minutes each. The last step is incubation with 10 μL of streptavidin-HRP for 30 min, followed by washing with 0.05 % Tween-20 in buffer and PBS buffer for 3 min. each. The immunosensor thus prepared was then placed in an electrochemical cell containing 10 mL pH 7.2 PBS buffer and 1 mM hydroquinone mediator. Rotating disk amperometry at 3000 rpm was done at -0.3 V vs SCE, and 0.4 mM H2O2 was injected to develop the catalytic signal. Standards consisted of IL-6 dissolved in undiluted calf serum.

3. Results and Discussion

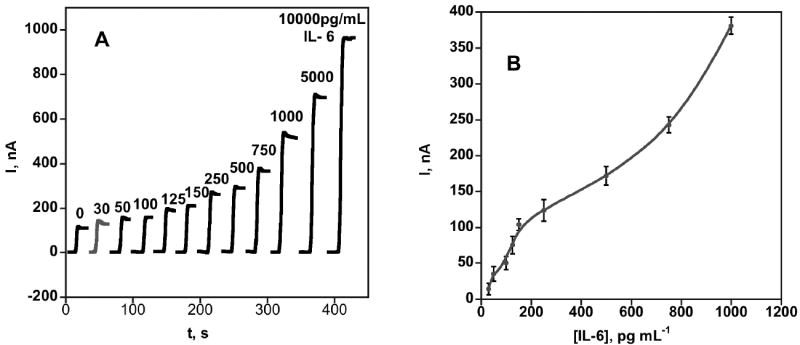

3.1. SWNT Immunosensor using Ab2-biotin-streptavidin-HRP14-16

The amperometric SWNT immunosensor response to IL-6 is shown in Figure 1A. Steady state current increased (Figure 1B) with IL-6 concentration over the range of 30-10,000 pg mL-1, but was linear only in the range 30-150 pg mL-1. Sensitivity was 3 nA cm-2 (pg/mL IL-6)-1 in this range with good device-to-device reproducibility as illustrated by the small error bars. The detection limit was 30 pg mL-1 measured as the zero IL-6 control signal plus three times the avg. noise (Figure 1A). Controls in Figure 1A represents a SWNT immunosensor without exposure to IL-6 but including the rest of the protocol, and response reflects the sum of residual NSB and direct reduction of H2O2.

Figure 1.

Amperometric response for SWNT immunosensors incubated with 10 μL undiluted calf serum containing IL-6, for 1 h, then with Ab2-streptavidin-HRP in 1 % BSA in pH 7.2 buffer. (A) Current at -0.3 V vs SCE and 3000 rpm in PBS buffer containing 1 mM hydroquinone upon injecting H2O2 to 0.4 mM. Each curve represents a different sensor at a different IL-6 concentration (B) Influence of IL-6 concentration on steady state amperometric current for SWNT immunosensor. Error bars represent device-to-device standard deviation (n = 4).

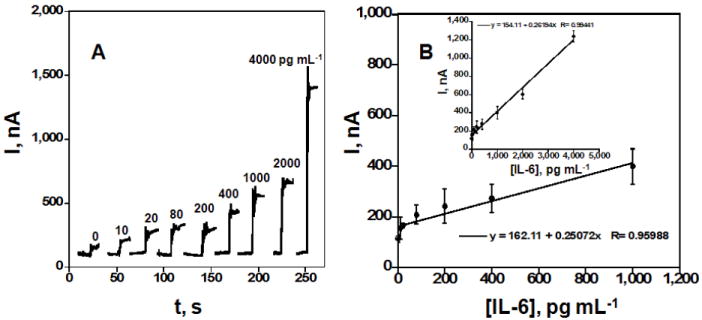

3.2. GSH-AuNP Immunosensor using Ab2-biotin-streptavidin-HRP14-16

Here procedures were identical as above, but the sensor surface features a monolayer of 5 nm GHS-AuNPs adsorbed on a positively charged polyion underlayer [26]. Responses to IL-6 in calf serum are shown in Figure 2A. Similar to the SWNT immunosensor, the best performance was achieved using optimized concentrations of the primary and secondary anti IL-6 antibodies and a combination of BSA and Tween-20 blocking to minimize NSB. The steady state current increased linearly (Figure 2B) with IL-6 concentration over the range of 10-4000 pg mL-1. This linear dynamic range was much larger than the 30-200 pg mL-1 for the SWNT immunosensor. A sensitivity of 1.6 nA cm-2 (pg/mL IL-6)-1 was achieved with excellent device-to-device reproducibility as illustrated by the small error bars. The detection limit was 10 pg mL-1, 3-fold better than the SWNT immunosensor. Results suggest that the gold nanoparticle-based sensors provide better linear range and detection limit than SWNT sensors, at the cost of some sensitivity. Controls in Figure 2A represent a full GSH-AuNPs immunosensor without exposure to IL-6, and the amperometric response reflects the sum of residual NSB and direct reduction of H2O2.

Figure 2.

Amperometric response for GSH-AuNPs immunosensors incubated with 10 μL undiluted calf serum containing IL-6, for 1 h, then with Ab2-streptavidin-HRP in 1 % BSA in pH 7.2 buffer. (A) Current at -0.3 V vs SCE and 3000 rpm in PBS buffer containing 1 mM hydroquinone upon injecting H2O2 to 0.4 mM. Each curve represents a different sensor at a different IL-6 concentration (B) Influence of IL-6 over two ranges of concentration on steady state amperometric current for SWNT immunosensor. Error bars represent device-to-device standard deviation (n = 4).

4. Conclusion

Sensitive sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensors based on SWNTs and GSH-AuNPs were compared for the detection of human IL-6 cancer biomarker in serum. The GSH-AuNPs immunosensor offered a lower low detection limit of 10 pg mL-1 (500 amol mL-1) in the 10 μL serum sample, 3-fold better than 30 pg mL-1 (1500 amol mL-1) observed with SWNT forest for the same protocol. The GSH-AuNP approach also gave a much larger linear dynamic range, at the expense of a 2-fold decrease in sensitivity. Results suggest that for both immunosensor platform 1% BSA in PBS buffer for NSB blocking, Tween-20 washing steps and optimizing the concentration of Ab1 and biotinylated Ab2 are highly effective in minimizing NSB and ensuring high sensitivity. While the SWNT system provides better sensitivity in the very lowest concentration range, its detection limit is too high to be useful for serum samples with normal IL-6 levels. The AuNP provided better overall analytical performance with detection limit of 10 pg mL-1 approaching the IL-6 normal range (≤6 pg mL-1) and sensitivity suitable for real serum sample analyses. The better sensitivity of the AuNP platform is likely to be related to larger amounts of capture antibody and decreased NSB. Since it would be most useful to accurately measure both normal and elevated levels of IL-6, we are currently exploring multi-labeled particles with thousands of HRPs per Ab2 [26] along with AuNP platforms to further enhance sensitivity and detection limit. In addition, we are exploring this technology in microfluidic systems using arrays of sensors for determination of multiple proteins in the same sample.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant number P20RR016457 from the National Center for Research Resource (NCRR), a component of the U. S. National Institute of Health (NIH), by grant no. ES013557 from NIEHS/NIH, and by the intramural programs of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH. JFR is grateful to Science Foundation Ireland for a Walton Research Fellowship in 2008/2009.

References

- 1.Sander C. Science. 2000;287:1977. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivas PR, Kramer BS, Srivastava S. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:698. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somers W, Stahl M, Seehra JS. EMBO J. 1997;16:989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riedel F, Zaiss I, Herzog D, Gotte K, Naim R, Hormann K. AntiCancer Res. 2005;25:2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2005 CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinoshita T, Ito H, Miki C. Cancer. 1999;85:2526. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990615)85:12<2526::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vita F, Romano C, Orditura M, Galizia G, Martinelli E, Lieto E, Catalano G. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:45. doi: 10.1089/107999001459150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise GJ, Marella VK, Talluri G, Shirazian D. J Urology. 2000;164:722. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilja H, Ulmert D, Vickers AJ. Nature Rev Cancer. 2008;8:268. doi: 10.1038/nrc2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Riedel F, Zaiss I, Herzog D, Götte K, Naim R, Hörman K. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williams TI, Toups KL, Saggese DA, Kalli KR, Cliby WA, Muddiman DC. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2936. doi: 10.1021/pr070041v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward MA, Catto JWF, Hamdy FC. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001;38:633. doi: 10.1258/0004563011901055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deckert F, Legay F. J Pharm & Biomed Anal. 2000;23:403. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou SF, Hsu WL, Hwang JM, Chen CY. Biosens & Bioelectron. 2004;19:1999. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haes AJ, Hall WP, Chang L, Klein WL, Van Duyne RP. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1029. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F, Persson B, Löfås S, Knoll W. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6765. doi: 10.1021/ac048937w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng J, Shan G, Maquieira A, Koivunen ME, Guo B, Hammock BD, Kennedy IM. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang W, Zhang CG, Qu HY, Yang HH, Xu JG. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;503:163. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seydack M. Biosen Bioelectron. 2005;20:2454. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koskinen JO, Vaarno J, Meltola NJ, Soini JT, Hänninen PE, Luotola J, Waris ME, Soini AE. Anal Biochem. 2004;328:210. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin T, Wei W, Yang L, Gao X, Gao Y. Sens Actuator B: Chem. 2006;117:286. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Rusling JF, Papadimitrakopolous F. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3214. doi: 10.1002/adma.200700665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J. Electroanalysis. 2007;19:769–776. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz E, Willner I. ChemPhysChem. 2004;5:1084–1104. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz E, Willner I, editors. Bioelectronics. Wiley-VCH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X, Munge B, Patel V, Jensen G, Bhirde A, Gong JD, Kim SN, Gillespie J, Gutkind JS, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Rusling JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11199. doi: 10.1021/ja062117e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mani V, Chikkaveeraiah BV, Patel V, Silvio Gutkind J, Rusling JF. ACSNano. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chattopadhyay D, Galeska I, Papadimitrikopoulos F. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9451. doi: 10.1021/ja0160243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu X, Kim SN, Papadimitrikopoulos F, Rusling JF. Molec Biosys. 2005;1:70. doi: 10.1039/b502124c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]