Abstract

The emerging field of global mass-based metabolomics provides a platform for discovering unknown metabolites and their specific biochemical pathways. We report the identification of a new endogenous metabolite, N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine and the use of a novel proteomics based method for the investigation of its protein interaction using metabolite immobilization on agarose beads. The metabolite was isolated from the organism Pyrococcus furiosus, and structurally characterized through an iterative process of synthesizing candidate molecules and comparative analysis using accurate mass LC-MS/MS. An approach developed for the selective preparation of N1-acetylthermospermine, one of the possible structures of the unknown metabolite, provides a convenient route to new polyamine derivatives through methylation on the N8 and N4 of the thermospermine scaffold. The biochemical role of the novel metabolite as well as that of two other polyamines: spermidine and agmatine is investigated through metabolite immobilization and incubation with native proteins. The identification of eleven proteins that uniquely bind with N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine, provides information on the role of this novel metabolite in the native organism. Identified proteins included hypothetical ones such as PF0607 and PF1199, and those involved in translation, DNA synthesis and the urea cycle like translation initiation factor IF-2, 50S ribosomal protein L14e, DNA-directed RNA polymerase, and ornithine carbamoyltransferase. The immobilization approach demonstrated here has the potential for application to other newly discovered endogenous metabolites found through untargeted metabolomics, as a preliminary screen for generating a list of proteins that could be further investigated for specific activity.

Introduction

The recent focus of metabolomics has been on discovering biomarkers, as well as uncovering fundamental biochemical information. The full structural characterization of biomarkers is required for gaining a larger understanding of biochemical changes for specific cellular perturbations.1,2 The chemical identity of a biomarker, especially in cases where the molecule is previously known, can allow the identification of biochemical pathways perturbed in a specific study.1 The use of multiple “omics” methodologies like metabolomics profiling and transcriptomics using DNA microarray analysis can potentially provide complementary information on pathways that can be targeted for the development of therapeutics. In cases where a completely new metabolite is identified, and information is not available about its role in the organism, clues can be ascertained from the investigation of its intramolecular interactions. Toward this end we present the full structural characterization of a new endogenous metabolite observed in P. furiosus, as well as an immobilization and proteomics strategy to initially screen the organism’s proteome to ascertain preliminary clues about the new metabolite’s role in the organism.

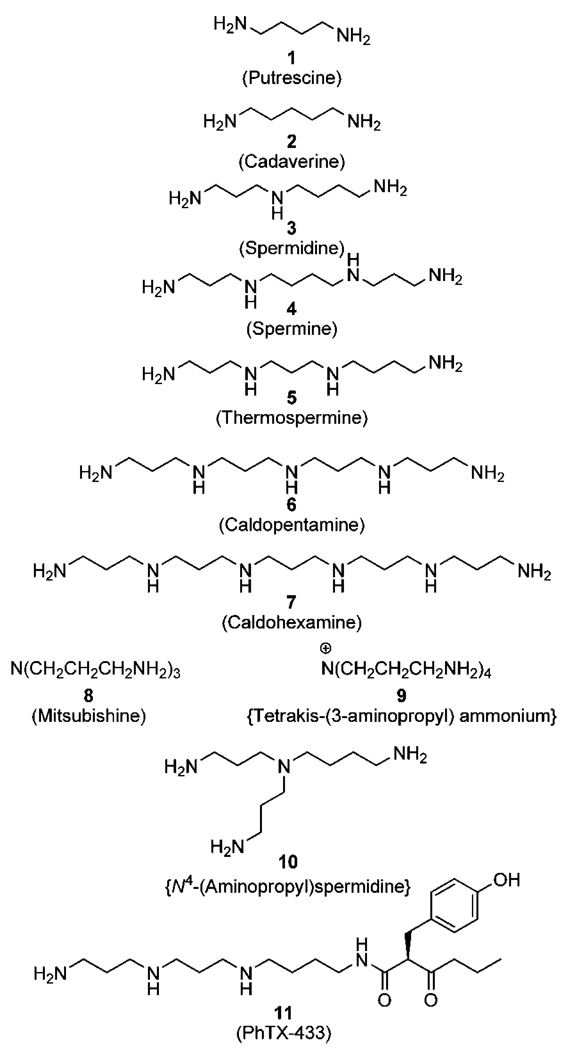

Polyamines such as putrescine 1, cadaverine 2, spermidine 3, spermine 4 are widely distributed in nature, and occur in all eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells (Chart 1).3,4 These flexible molecules play an important, biological role in cell growth and bind to phosphate residues of DNA, stabilizing the specific conformation of the latter. In addition, many functionalized polyamines possess important pharmacological properties being antitumor5–8 and antimalaria9 agents. Polyamine type toxin 11 (PhTX-433)10–12 isolated from orb-web spiders and certain parasitic wasps exhibit noncompetitive antagonist activity on acetylcholine (nAChRs) and glutamate (GluRs) receptors. Its bioactivity suppresses neurotransmission in mammalian brain which is extremely important in the treatment of a wide range of neurological dysfunctions, including Alzheimer’s disease. In 1979, Oshima discovered a new polyamine, thermospermine 5, in cells of Thermus themophilus,13 a thermophilic bacterium that grows optimally at 65 °C. Thermophiles are biochemically and evolutionarily unique organisms that have adapted to the challenges of molecular and structural stability of their higher temperature habitats. DNA, RNA and proteins can undergo irreversible changes at higher temperatures for most organisms, however, these deleterious effects are largely suppressed for thermophiles and especially hyperthermophiles, which are adapted to growing at >80 °C. Their unusual properties suggest that evolutionary history and adaptation to their geo-thermal habitats has led to the development of novel mechanisms of DNA and protein stabilization.14 The unusual thermal stability of hyperthermophiles is partially associated with the presence of polyamines, responsible for nucleic acid stabilization and supporting protein synthesis. Particularly the concentration of long polyamines (caldopentamine 6 and caldohexamine 7) and branched analogous (mitsubishine 8 and tetrakis-(3-aminopropyl) ammonium 9) was found to be significantly higher in T. thermophilus cells grown at 80 °C than in those grown at 65 °C.15 These findings support the hypothesis of their crucial role for thermophilic cell stability at higher temperatures.

Chart 1.

Common Polyamines Uncovered in Nature

Recently, we showed that during a cold adaptation response, certain polyamine metabolites were up-regulated upon cold adaptation.16 During this analysis, a novel metabolite was found to be highly up-regulated upon cold adaptation to 72 °C (normally 95 °C). The structural characterization of this metabolite was performed through an iterative process of chemical synthesis and characterization by collision induced dissociation (CID) as discussed here. The discovery of a novel metabolite opens the door to many questions about its biochemical role in the organism, and enzymes which may regulate its concentration. We present results from a metabolite immobilization and proteomics based assay which has been developed to analyze the new metabolite’s interactome in comparison to two other polyamine metabolites from the urea cycle.

Results and Discussion

Structural Hypothesis Driven by MS/MS Characterization of Novel Metabolite

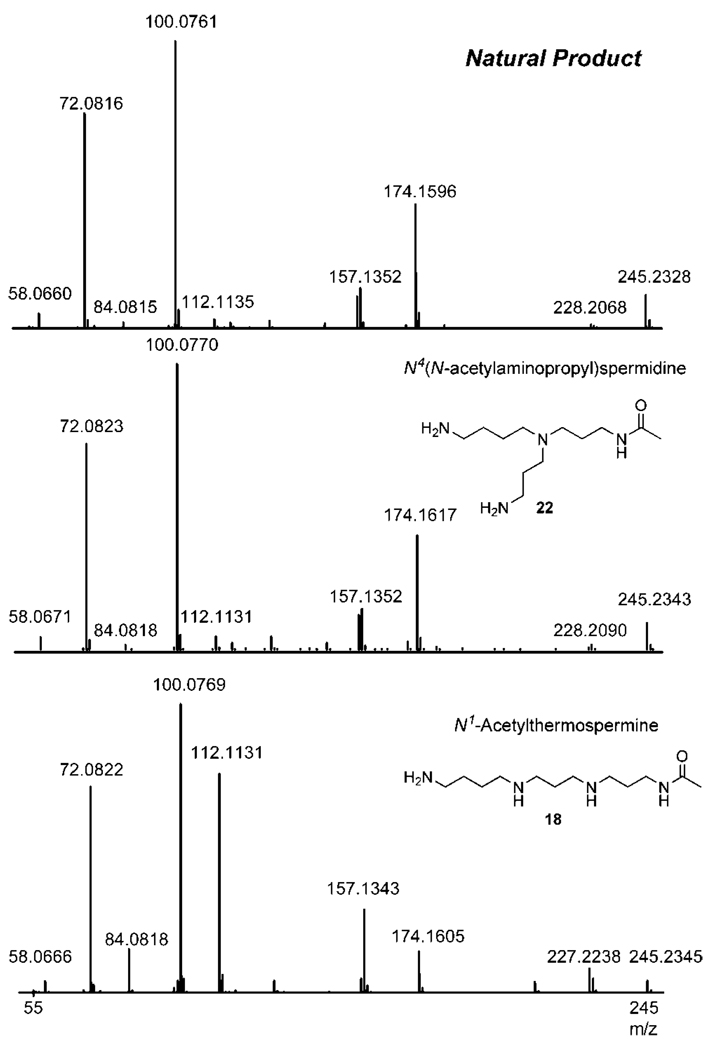

The starting point for the structural characterization of the novel metabolite was the accurate CID data of the natural product obtained on a q-TOF mass spectrometer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fragmentation pattern for a new endogenous metabolite from Pyrococcus furiosus, N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 and N1-acetylthermospermine 18 under identical experimental conditions.

An analysis of the accurate masses of the fragment ions, and their possible elemental compositions allowed us to propose that it was an N-acetyl derivative of C10H26N4. Among known polyamines only thermospermine 5 and its branched analog N4-(aminopropyl)spermidine 10 match with the formula. A fragment ion at 100.0761 Da was only 4.1 ppm away from C5H10NO which corresponds to an acetylated aminopropyl group. This experimental evidence places the acetyl group squarely on the three carbon linker of the candidate polyamine. Only two possible compounds, N1-acetylthermospermine and N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl) spermidine, meet this requirement. To confidently assign the correct structure of this natural product through comparative MS/MS under identical experimental conditions, a synthesis of the candidate compounds had to be first elaborated.

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

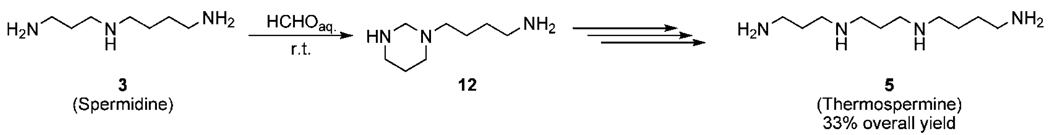

The main challenge to overcome in preparation of polyamines is differentiation of amine functions which allows in turn for further selective modifications. Different approaches to this problem have been presented including orthogonal protective group method and solid-state synthesis.17–19 An elegant solution to this drawback was described in 1980 in the first reported synthesis of thermospermine (Scheme 1).20

Scheme 1.

Differentiation of the Amine Functions in the Synthesis of Thermospermine 5

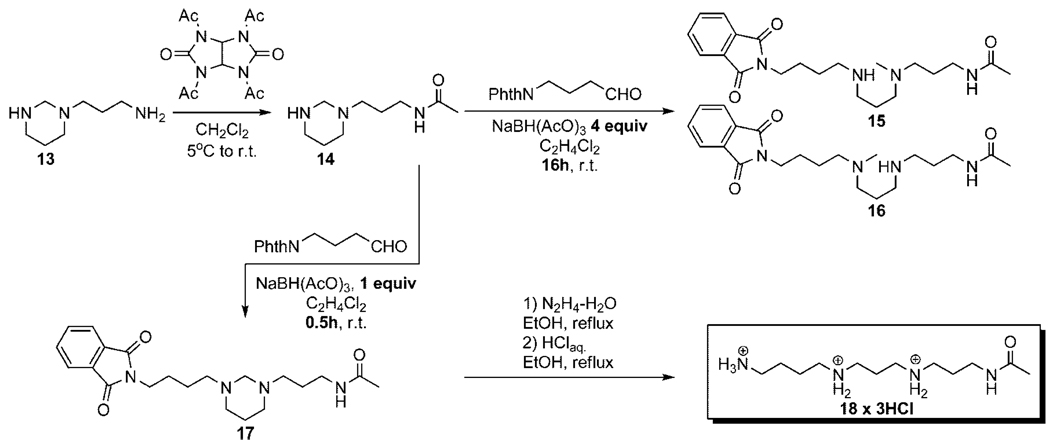

In this method, spermidine 3 was protected as a hexahydropyrimidine derivative 12, containing primary, secondary and tertiary functional groups which can be selectively modified and after few additional steps thermospermine 5 was obtained with 33% overall yield. Unfortunately this straightforward method can not be used for the preparation of N1-acetylthermospermine; hence direct acylation of the polyamine 5 can lead only to a multicomponent mixture of isomeric products, extremely difficult to separate. However, utility of the first step of the presented method can be employed for the synthesis of N1-acetylthermospermine. Starting from 1,2-bis(3-aminopropyl) amine, its reaction with formaldehyde proceeds smoothly to a hexahydropyrimidine derivative 1321 (Scheme 2). Selective modification of the amine 13 at its primary group was achieved, using mild acylation reagent N,N′,N′′,N′′′-tetraacetylglycoluril22 and the product 14 was obtained with 65% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of N1-Acetylthermospermine 18

Interestingly, next step, reductive amination is strongly dependent on the reaction time and amount of the reducing agent; namely using equimolar amount of NaBH(OAc)3 after 30 min only desired product 17 was isolated with 71% yield. On the contrary, prolongation of the reaction time to 16 h in the presence of 4eq. of NaBH(OAc)3 provides two unknown isomeric products in the ratio of 1.8:1 (overall yield 49%) and with MW = 388 Da, 2 Da higher than for desired product 17. NMR analysis of new products show very similar spectra as for compound 17 however, 13C NMR does not show characteristic signal from the NCH2N group at ~76 ppm and 1H NMR analysis shows an additional CH3 group. According to these findings new structures were proposed as N4 and N8 methylated derivatives 15 and 16 respectively. Geminal diamines have similar reactivity to their imine form; therefore formation of these products could be explained by reducing of immonium species by opening of the aminal 17. This phenomenon for hexahydropyrimidines has been described before,23–25 however never for the thermospermine scaffold and without detailed structural analysis. Derivatives 15 and 16 can be easily elaborated and serve as interesting intermediates in the synthesis of novel thermospermine-based analogous. Thus appropriate assignment of the structures for 15 and 16 was necessary and required investigation by means of 2D NMR experiments: HMQC (proton-carbon correlation) and HMBC (long-range proton-carbon correlation) (see Supporting Information). According to these results compound 15 (N4-Me) has Rf = 0.31 (17:2:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq., lower layer as eluant) whereas compound 16 (N8-Me) has Rf = 0.23 (analogous conditions) and were obtained with 17% and 32% yield respectively without further optimization.

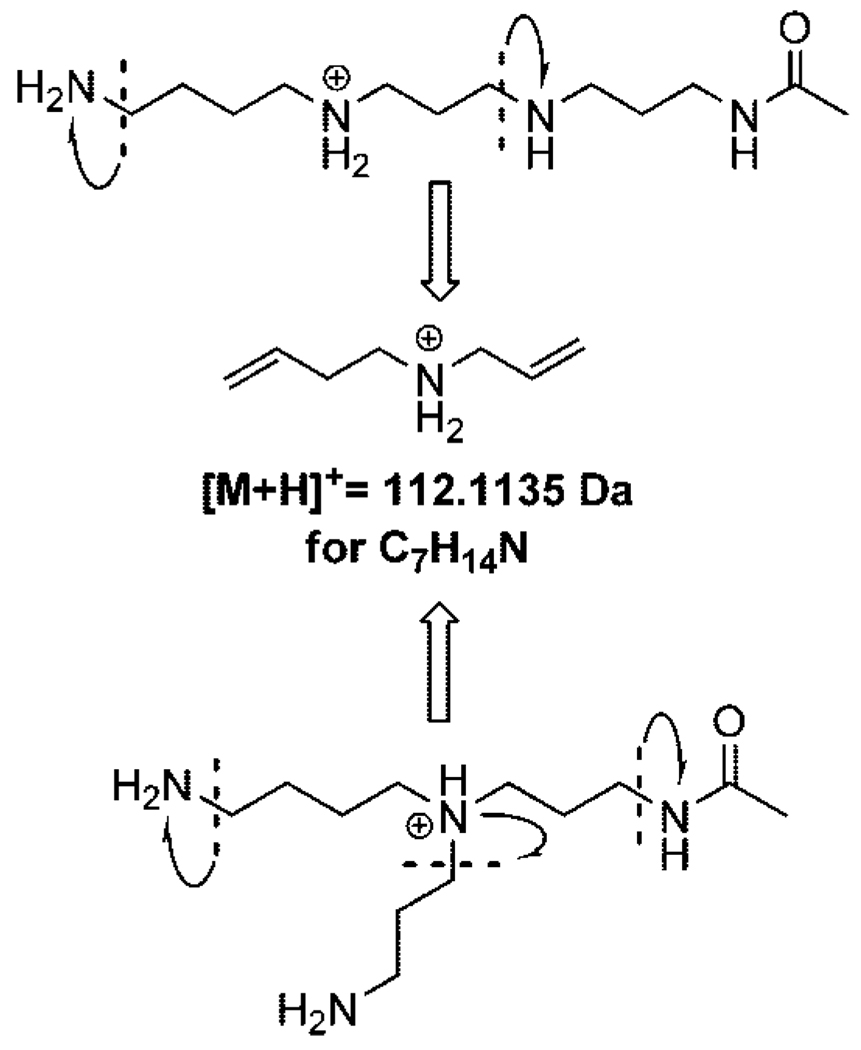

The final step in the synthesis of N1-acetylthermospermine 18 is one pot, two steps global deprotection by stirring compound 17 under reflux with an excess of hydrazine hydrate and subsequently HClaq. to hydrolyze the hexahydropyrimidine ring. Polyamine derivative 18 has been isolated as hydrochloride salt with 66% yield; free base equivalent undergoes decomposition at room temperature and is recommended to store it as its more stable protonated form. Accurate collision induced dissociation mass spectra of the N1-acetylthermospermine 18 exhibits significant similarity to this obtained from the natural sample, however much higher intensity of the peak with m/z = 112.1135 Da suggests a different structure of the desired metabolite (Figure 1). The accurate mass of the fragment ion indicates that the only possible molecular formula for this ion is C7H14N. This fragment ion can be produced from both the linear and branched isomers by mechanisms outlined in Figure 2. Significantly lower intensity of this peak in the experimental MS/MS data of the metabolite is consistent with the branched structure of N4(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine since it would require breaking more bonds to generate this fragment ion, and therefore making this process kinetically less favorable than for the case of the linear isomer. These facts were all pointing to the second possible branched structure being the correct identity of the metabolite.

Figure 2.

Ion at m/z=112.1135 corresponding to C7H14N in the CID spectrum of the natural product showed a markedly lower intensity compared to the synthesized linear isomer and is consistent with the branched structure.

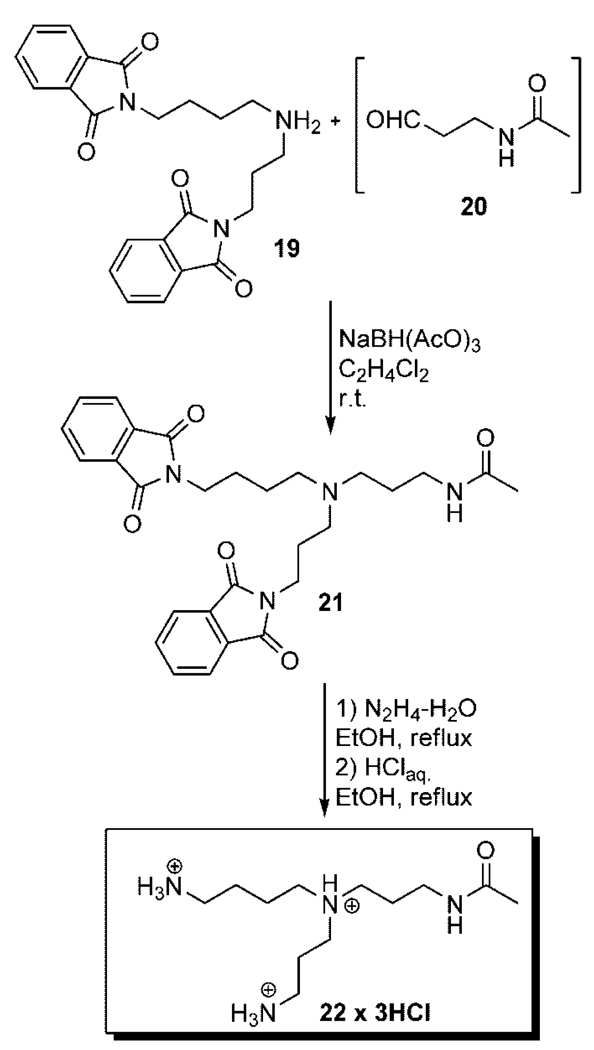

The second proposed structure of the metabolite is a branched analog of N1-acetylthermospermine 18; N-acetylated derivative of N4-aminopropylspermidine 10. Although the preparation of the polyamine 10 had been described26 its selective acylation can be problematic and lead to multicomponent reaction mixture. Therefore we decided to synthesize the branched analog of 18 using as a key step reductive amination reaction between diprotected spermidine 1927,28 and the aldehyde 2029 to obtain the product 21 with 77% yield (Scheme 3). Final deprotection step was performed using standard procedures and the product 22 was isolated as the hydrochloride salt. MS/MS analysis for the branched N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 gives identical results to the natural sample and incontrovertibly prove the structure of the new endogenous metabolite (Figure 1).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of N4-(N-Acetylaminopropyl)spermidine22

Metabolite Immobilization and Proteomic Analysis

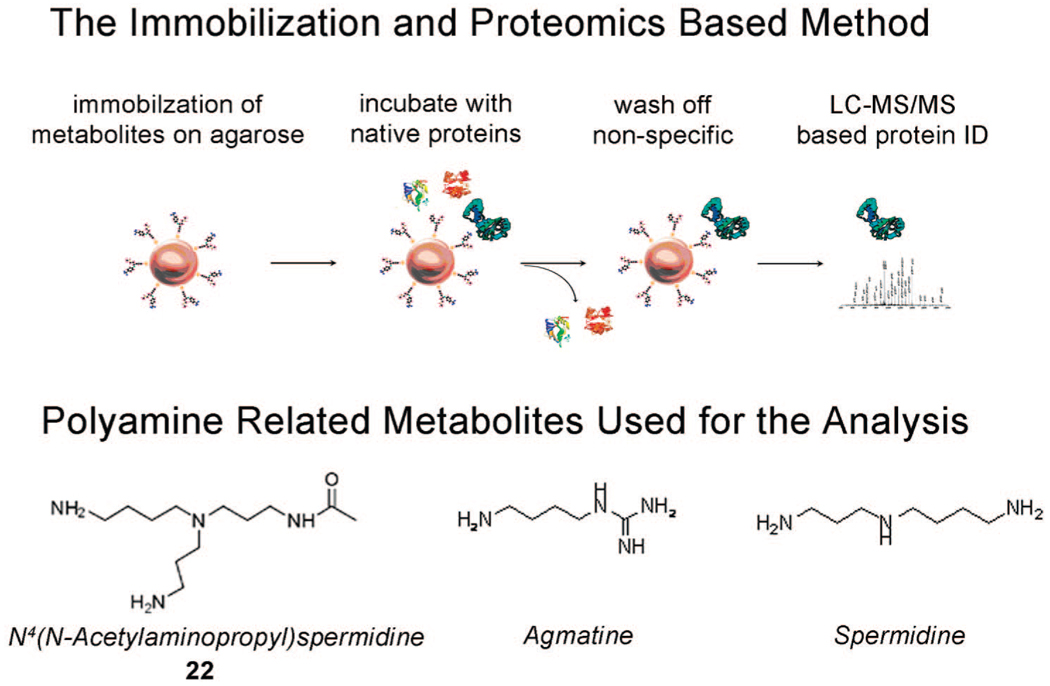

The first characterization of N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 as a novel metabolite and the lack of any enzymes that play a role in its biosynthesis and transformation opens the door to discovering these pathways. Furthermore, being able to synthesize it in bulk and high purity allows the study of its biomolecular transformations. We devised a strategy involving the immobilization of N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 and two other polyamines: spermidine and agmatine on agarose beads to identify metabolite-protein interactions through proteomic analysis. While there is evidence for a known polyamine biosynthesis pathway for other polyamines related molecules spermidine and agmatine,30 this information is not available for the newly identified metabolite N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22. Our technique was designed to allow for the characterization of captured proteins which interact with the molecules of interest is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Metabolite immobilization, incubation with cell lysate, followed by proteomic analysis allows a first look at identifying proteins which interact with a novel metabolite of interest.

For a hyperthermophile which grows optimally at 95 °C, these interactions may be even more stabilized at lower incubation temperatures (37 °C) and therefore facilitate this type of analysis. While some of proteins identified may represent secondary interactions, this method can still be useful as an initial screen to identify candidate proteins which can be cloned and tested for specific activity such as the conversion of N4-aminopropylspermidine to N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 through acetylation, and the transfer of an aminopropyl group to spermidine to form N4-aminopropylspermidine 10. Since this metabolite was initially targeted due to its significant up-regulation upon the stress induced cold adaptation response to 72 °C vs the optimal temperature of 95 °C,16 the immobilization experiments were done using incubation with proteins from cells adapted at both temperatures. Using agarose beads, the metabolites of interest: N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22, spermidine and agmatine were immobilized using the Microlink cross-linking kit from Pierce. This kit employs the strategy of amine reactive linkers on beads which can tether the desired molecule to the surface, as it is allowed to react or interact with the medium of choice. A negative control was also used that consisted of beads that underwent the same processing with just the incubation buffer instead of the solution containing the metabolites. For comparison purposes, two other known metabolites related to the polyamine biosynthesis pathway, spermidine and agmatine were chosen to undergo the same processing. While many proteins identified to interact with N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 were common with the other amine metabolites agmatine and spermidine, there were some proteins that were found to uniquely bind N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl) spermidine 22 and were unambiguously identified through LC-MS/MS analysis of more than two unique peptides at scores corresponding to 95% confidence level and <1% false discovery rate. Many proteins identified were found to commonly bind all three polyamines. While all three molecules are positively charged, and many of their interactions may represent purely electrostatic interactions, some of these may also be functional in the organism. The proteins found to bind the novel metabolite N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Proteins that Bind N4-(N-Acetylaminopropyl)spermidine22 from Cells Grown at 72 °Ca

| # | annotation | accession | MW (kDa) | peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | phosphoenolpyruvate synthase | gi|18976415 | 90 | 3 |

| 2 | thermosome, single subunit | gi|18978346 | 60 | 11 |

| 3 | archaeal histone a1 | gi|18978203 | 7 | 4 |

| 4 | chromatin protein | gi|18978253 | 10 | 3 |

| 5 | pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | gi|18977343 | 20 | 5 |

| 6 | 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | gi|18978145 | 20 | 4 |

| 7 | 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | gi|18978142 | 18 | 5 |

| 8 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | gi|18977345 | 43 | 2 |

| 9 | 50S ribosomal protein L12P | gi|18978366 | 11 | 2 |

| 10 | phospho-sugar mutase | gi|33359571 | 27 | 2 |

| 11 | hypothetical protein PF0547 | gi|18976919 | 51 | 2 |

| 12 | 30S ribosomal protein S27e | gi|18976590 | 7 | 2 |

| 13 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | gi|18977936 | 127 | 2 |

| 14 | indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit a | gi|18976905 | 71 | 3 |

| 15 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | gi|18978238 | 44 | 3 |

| 16 | 50S ribosomal protein L7Ae | gi|18977739 | 14 | 2 |

| 17 | phosphopyruvate hydratase | gi|18976587 | 47 | 2 |

| 18 | pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit alpha | gi|18977338 | 44 | 2 |

| 19 | acetyl-CoA synthetase | gi|18978159 | 26 | 3 |

| 20 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunitA′′ | gi|18977934 | 44 | 3 |

| 21 | replication factor C small subunit | gi|18976465 | 98 | 2 |

| 22 | translation initiation factor IF-2 subunit alpha | gi|18977512 | 32 | 2 |

| 23 | ferredoxin--NADP(+) reductase subunit alpha | gi|18977700 | 31 | 2 |

| 24 | elongation factor 1-alpha | gi|18977747 | 48 | 2 |

| 25 | glutamine synthetase i | gi|18976822 | 50 | 2 |

| 26 | 2-isopropylmalate synthase | gi|18977309 | 55 | 2 |

| 27 | hypothetical protein PF1199 | gi|18977571 | 21 | 2 |

| 28 | nifS protein | gi|18976536 | 45 | 2 |

| 29 | 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase alpha | gi|18978140 | 44 | 2 |

| 30 | hypothetical protein PF0607 | gi|18976979 | 26 | 2 |

| 31 | ornithine carbamoyltransferase | gi|18976966 | 35 | 2 |

Proteins highlighted in bold were uniquely observed for N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine.

Table 2.

Proteins that Bind N4-(N-Acetylaminopropyl)spermidine 22 from Cells Grown at 95 °Ca

| # | annotation | accession | MW (kDa) | peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit gamma | gi|18977343 | 20 | 9 |

| 2 | archaeal histone a1 | gi|18978203 | 7 | 2 |

| 3 | chromatin protein | gi|18978253 | 10 | 3 |

| 4 | phospho-sugar mutase | gi|33359571 | 27 | 2 |

| 5 | 30S ribosomal protein S28e | gi|18977740 | 8 | 3 |

| 6 | 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | gi|18978145 | 20 | 5 |

| 7 | 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | gi|18978142 | 18 | 5 |

| 8 | 50S ribosomal protein L12P | gi|18978366 | 11 | 2 |

| 9 | indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit a | gi|18976905 | 71 | 5 |

| 10 | pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase subunit alpha | gi|18977338 | 44 | 4 |

| 11 | small nuclear ribonucleoprotein | gi|18977914 | 8 | 3 |

| 12 | translation initiation factor IF-2 subunit beta | gi|18976853 | 16 | 3 |

| 13 | transcriptional regulatory protein, asnC family | gi|18978425 | 17 | 2 |

| 14 | 50S ribosomal protein L7Ae | gi|18977739 | 14 | 4 |

| 15 | indolepyruvate oxidoreductase subunit B | gi|18976906 | 24 | 2 |

| 16 | metal-dependent hydrolase | gi|18978136 | 25 | 4 |

| 17 | elongation factor 1-alpha | gi|18977747 | 48 | 3 |

| 18 | hypothetical protein PF1557 | gi|18977929 | 30 | 4 |

| 19 | translation initiation factor IF-2 subunit alpha | gi|18977512 | 32 | 2 |

| 20 | 30S ribosomal protein S27e | gi|18976590 | 7 | 2 |

| 21 | translation initiation factor IF-5A | gi|18977636 | 15 | 2 |

| 22 | 50S ribosomal protein L14e | gi|18977191 | 9 | 2 |

Proteins highlighted in bold were uniquely observed for N4-(N-acetylaminopropyl)spermidine.

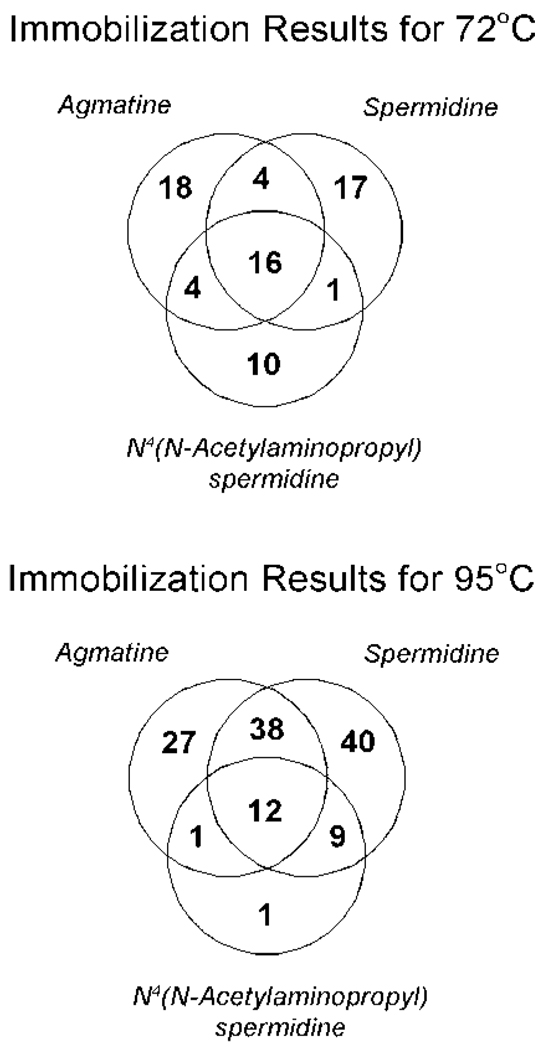

Eleven of these, highlighted in bold in Table 1 and Table 2, were found to uniquely bind the newly identified metabolite and are unambiguously identified through the MS/MS of more than two unique peptides. The Venn diagrams shown in Figure 4 highlight the proteins found to be in common between the different analyses and the ones found to uniquely bind each metabolite.

Figure 4.

Results of the proteomic analyses as a Venn diagram showing the distribution of interacting proteins identified as unique or common to the three compounds of interest at the two growth temperatures studied.

This is especially helpful since the natural pathway for the biosynthesis of the novel metabolite still remains to be uncovered. For spermidine immobilization, two proteins (S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme (PF1930) and S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (PF1866)) directly involved in its biosynthesis were identified.31 Many other proteins identified for spermidine immobilization are involved in translation such as translation elongation faction ef1 (PF1375), LSU ribosomal protein L7AE (PF1367), translation elongation factor eIF-5a (PF1264). Spermidine is a well characterized polyamine and is known to play a critical role for eukaryotic organisms in translation, ribosomal assembly and protein elongation and their interaction may reflect the specific affinity of spermidine for these proteins.32–34 While some of proteins identified may represent secondary interactions with the newly discovered metabolite, the immobilization/proteomics screen presented here can be a powerful tool for getting a glimpse of where a previously unknown metabolite discovered through untargeted metabolomics, fits into the biochemical landscape. This method which is a first step toward understanding the role of the new metabolite can identify candidate proteins for designing subsequent targeted enzymatic assays for further functional analysis.

Conclusion

In summary, the structural characterization of a novel metabolite is demonstrated using a hypothesis driven approach that involved an iterative process of MS/MS characterization and chemical synthesis of candidate structures. An initial accurate tandem MS analysis on a q-TOF mass spectrometer was used to propose two possible structures of N1-acetylthermospermine 18 and N4-(N-acetyl)aminopropylspermidine 22. The steps toward the identification of this new polyamine metabolite involved working out the synthesis of the candidate compounds which were not commercially available. A convenient and selective approach was elaborated for the synthesis of N1-acetylthermospermine 18, and additionally two new compounds 15 and 16 methylated on N4 or N8 of the thermo-spermine scaffold were obtained and structurally characterized. These building blocks are useful starting materials which can be easily modified and provide new opportunities in the synthesis of bioactive compounds based on the thermospermine scaffold. In an effort to understand the biochemical role of this novel metabolite, a proteomics based screening method was developed to probe a cell lysate of P. furiosus’ lysate for its native metabolite-protein interactions. Many of the proteins identified are linked to the urea cycle, protein and DNA synthesis where it, like other compounds involved in the polyamine biosynthetic pathway may play a supportive role in the survival of the hyperthermophile under extreme environmental conditions.

Experimental Section

General Materials and Methods: Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The endogenous metabolite was extracted from P. furiosus as previously described.16 The accurate mass measurements and LC-MS/MS characterization of the endogenous metabolite was performed on the Agilent q-TOF mass spectrometer using internal calibration with the Agilent tune mix using dual spray ionization. Comparative MS/MS of the endogenous metabolite and the synthetic standards was performed on the q-TOF using collision energy of 20 eV.

Immobilization of Metabolites and Proteomics Analysis

Spermidine was immobilized on sepharose beads using chemical linkage of amines with the commercially available MicroLink kit (Pierce). A sample of the cytoplasmic fraction of P. furiosus (100 µL) growing at 72 or 95 °C was diluted with Coupling Buffer in a 1:1 ratio. A 1.0 mg/mL solution of spermidine was prepared in Coupling buffer.

The beads in the column were conditioned with 2 aliquots of 300 µL Coupling Buffer, followed by the addition of 2 µL of 5 M sodium cyanoborohydride. Subsequently, 200 µL of spermidine solution and 2 µL of sodium cyanoborohydride were added. Two columns, one with spermidine and one without (control) were incubated at room temperatures for 4 h with gentle rocking followed by three times washing using Coupling Buffer (each time 300 µL). To deactivate remaining active binding sites, 600 µL of Quenching Buffer was added in two portions. Thereafter reaction mixture was incubated with 200 µL of Quenching Buffer and 4 µL of 5 M sodium cyanoborohydride at room temperatures for 30 min gently mixing after every 15 min and centrifuge after this time. Finally, the columns were washed twice with 300 µL Wash Solution. The same procedure was using for Coupling Buffer. To form the Gelbound Complex, 200 µL of the cytoplasmic extract of P. furiosus sample was added directly to the column and incubated at room temperatures overnight with gentle rocking. To reduce possible nonspecific interactions, the column was washed 3 volumes of 300 µL of 0.5 M NaCl containing 0.05% Rapigest. Each time column was gently invert 10 times and centrifuged. After this 300 µL of Coupling Buffer was added to the column and it was gently inverted 10 times and centrifuged. This entire washing step was repeated once. Elution of bound proteins was done by incubation at room temperatures for 10 min with 100 µL of ImmunoPure Elution Buffer. This step was repeated twice until a Bradford Assay showed no detectable protein. The proteins were reduced (10 mM dithiothrietol), alkylated (55 mM iodoacetamide) and digested with trypsin overnight. The digestion was quenched by driving the pH of the solution to 4 using 0.1% formic acid.

An analytical column/nanoelectrospray tip (75 µm inner diameter, 15 cm in length) which was fabricated with a P-2000 (Sutter Instruments) laser puller and packed with C18 resin (5 µm particle size, Agilent Zorbax SB) under high pressure, was used to separate the peptides prior to their analysis with a LTQ mass spectrometer in data-dependent MS/MS mode. The reverse phase gradient separation was performed using water and acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) as the mobile phases. The gradient started with 5% acetonitrile, was ramped to 8% acetonitrile over 5 min, then to 35% over 113 min, then to 55% over 12 min, then ramped up to 98% and maintained for 15 min (wash) before a re-equilibration at 5% for 15 min. MS/MS analysis was performed on the LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo) using 2 kV at the tip. One MS spectrum was followed by 4 MS/MS scans on the most abundant ions after the application of the dynamic exclusion list.

Tandem mass spectra were subjected to peak picking using Xcalibur (Thermo Electron Corporation, version 2.0 SR2). Protein identification was performed using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, UK, version 2.1.04) at the 95% confidence level using tryptic peptides derived from the NCBI annotation of the P. furiosus genome (June 6, 2008). Protein hits were thresholded using an ion score of 26 corresponding to the identity score with >95% confidence in Mascot. This corresponded to an average false discovery rate of <2.0% for all the searches for each peptide based identification. Mascot was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.80 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 2.0 Da. Iodoacetamide derivative of cysteine and oxidation of methionine were specified in Mascot as fixed and variable modifications, respectively. The enzyme was selected as trypsin with a maximum of 1 missed cleavage allowed for the search. The fragmentation pattern was optimized for the instrument used by selecting this Mascot search parameter as “ESI-trap”.

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

All of the chemical reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purifications. The 1D NMR spectra were obtained on Varian Inova 400 MHz; 2D NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker DRX-600 equipped with a 5 mm DCH cryoprobe. The chemical shifts were referenced to residual CHCl3 (δH 7.26 ppm) and CDCl3 (δC 77.0 ppm). High-accuracy mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent ESI-TOF mass spectrometer. Reactions were monitored by LCMS analysis (Hewlett-Packard Series 1100) and/or TLC chromatography using Merck TLC Silica Gel 60 F254 plates and visualized by staining with cerium molybdate (Hanessian’s Stain), ninhydrin or by absorbance of UV light at 254 nm. Crude reaction mixtures were purified by column chromatography using Merck Silica Gel 60 as stationary phase and CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq. (lower layer) as a solvent system.

Compound 14

To a stirred solution of 1321 (2.50 g, 17.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (130 mL) cooled to 5 °C, solid N,N′,N′′,N′′′-tetraacetylglycoluril (2.58 g, 8.3 mmol) was added. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight. After filtration, the solution was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel; 27:2:1 CH2Cl2: MeOH:NH3aq.) to give yellowish oil, 2.1 g (65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 6.95 (br s, 1H, NHCO), 3.32 (bs, 2H, NCH2N), 3.25-3.20 (m, 2H), 2.76 (br t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (br s, 2H), 2.38 (br s, 2H), 2.27 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.89 (s, 3H, Me), 1.62-1.52 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=169.9, 69.7, 53.6, 52.8, 44.9, 38.9, 27.0, 25.4, 23.1. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C9H20N3O [M + H]+: 186.1606 found: 186.1597.

Compound 15

To the mixture of 4-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)butanal35 (1 g, 4.6 mmol) and 14 (0.85 g, 4.6 mmol) in C2H4Cl2 (60 mL), NaBH(OAc)3 (3.89 g, 18.4 mmol) was added. Reaction was carried out for 16 h at room temperature and after evaporation the residue was dissolved in 1 M HCl/CH2Cl2 and washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 50 mL). Aquatic layer was neutralized with 2 M NaOH and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). Combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and after filtration and evaporation, reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography (silica gel; 27: 2:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.) to give 15 (0.31 g, 17%) Rf = 0.31 (17:2:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.) and 16 (0.57 g, 32%) Rf = 0.23 (17:2:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.) as colorless oils. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.79-7.77 (m, 2H), 7.68-7.66 (m, 2H), 7.11 (br s, 1H, NHCO), 3.66 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.26-3.22 (m, 2H), 2.59 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 4H), 2.37-2.32 (m, 4H), 2.14 (s, 3H, NMe), 1.89 (s, 3H, COMe), 1.71-1.56 (m, 6H), 1.52-1.45 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 169.9, 168.3, 133.8, 132.0, 123.0, 56.4, 56.2, 49.4, 48.5, 41.9, 39.0, 37.7, 27.5, 27.1, 26.3, 25.8, 23.2. 13C DEPT (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 134.1 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 56.7 (CH2), 56.5 (CH2), 49.7 (CH2), 48.8 (CH2), 42.2 (CH3), 39.3 (CH2), 38.0 (CH2), 27.8 (CH2), 27.4 (CH2), 26.6 (CH2), 26.1 (CH2), 23.5 (CH3). ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C21H33N4O3 [M + H]+: 389.2553 found: 389.2543.

Compound 16

Title compound was obtained together with 15. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.78-7.76 (m, 2H), 7.67-7.65 (m, 2H), 6.96 (br s, 1H, NHCO), 3.64 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.28-3.23 (m, 2H), 2.64 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.56 (t, J = 6.8, 2H), 2.33-2.27 (m, 4H), 2.12 (s, 3H, NCH3), 1.89 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.67-1.54 (m, 6H), 1.48-1.40 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 169.8, 168.2, 133.8, 131.9, 123.0, 57.1, 56.0, 48.4, 48.3, 42.0, 38.9, 37.7, 28.6, 27.5, 26.4, 24.5, 23.2. 13C DEPT (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 134.1 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 57.4 (CH2), 56.4 (CH2), 48.7 (CH2), 48.6 (CH2), 42.4 (CH3), 39.2 (CH2), 38.0 (CH2), 29.0 (CH2), 27.8 (CH2), 26.7 (CH2), 24.8 (CH2), 23.5 (CH3). ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C21H33N4O3 [M + H]+: 389.2553 found:389.2545.

Compound 17

Title compound was synthesized analogously as for 15 and 16 using 1eq. of NaBH(OAc)3 and carried out reaction for 30 min. Purification by column chromatography (silica gel; 17:2:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.) give colorless oil, Rf=0.51 (17:2:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.), yield 71%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.80-7.78 (m, 2H), 7.69-7.67 (m, 2H), 6.99 (br s, 1H, NHCO), 3.66 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.29-3.25 (m, 2H), 3.06 (br s, 2H), 2.44 (br s, 4H), 2.40-2.33 (m, 4H), 1.90 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.71-1.58 (m, 6H), 1.52-1.46 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 169.9, 168.3, 133.8, 132.0, 123.0, 76.1, 54.4, 53.8, 52.4, 52.1, 39.1, 37.7, 26.4, 25.5, 24.4, 23.5, 23.3. 13C DEPT (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 134.1 (CH), 123.3 (CH), 76.4 (CH2), 54.7 (CH2), 54.1 (CH2), 52.7 (CH2), 52.4 (CH2), 39.4 (CH2), 38.0 (CH2), 26.7 (CH2), 25.8 (CH2), 24.7 (CH2), 23.8 (CH2), 23.6 (CH3). ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C21H31N4O3 [M + H]+: 387.2396 found: 387.2399.

N1-Acetylthermospermine Trihydrochloride 18 × 3HCl

The mixture of 17 (500 mg, 1.3 mmol) and hydrazine hydrate (71 mg, 1.4 mmol) in EtOH (15 mL) was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After, additional portion of hydrazine hydrate (35 mg, 0.7 mmol) was added continuing heating for 1 h. Subsequently to the reaction mixture the solution (1.3 mL of HClconc. in 5 mL EtOH) was added. After next 3 h of stirring under reflux, reaction was cooled to room temperature and evaporated. The residue was dissolved in small amount of water (15 mL), filtrated and supernatant liquid was evaporated again. Consecutively the residue was dissolved in small amount of water (5 mL), cooled to 5 °C and filtrated through Celite. After evaporation of the aquatic solution, the crude product was diluted with MeOH and cooled to 0 °C. Product was filtrated and dried under high vacuum to give white solid (300 mg, 66%), mp decomposition >200 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ = 3.17 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 3.08-2.92 (m, 10H), 2.05-1.97 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.83-1.76 (m, 2H), 1.73-1.60 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ = 174.9, 47.3, 45.4, 44.71, 44.67, 39.0, 36.3, 25.7, 24.1, 22.95, 22.89, 22.0. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C12H29N4O [M + H]+: 245.2341 found: 245.2337.

Compound 19.27,28

To the mixture of N-ethoxycarbonylphthalimide (15.6 g, 71.2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (350 mL) a solution of spermidine 3 (5 g, 34.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (170 mL) was added dropwise within 30 min, then the reaction was carried out for the further 2 h at room temperature. After evaporation crude product was purified by crystallization from EtOH, to give white solid (13.4 g, 96%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.81-7.77 (m, 4H), 7.69-7.64 (m, 4H), 3.71 (t, J = 7.2, =2H), 3.65 (t, J = 7.2, 2H), 2.61-2.56 (m, 4H), 1.85-1.78 (m, 2H), 1.71-1.64 (m, 2H), 1.57-1.43 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=168.3, 168.28, 133.77, 133.75, 132.04, 132.03, 123.08, 123.05, 49.2, 46.8, 37.7, 35.8, 28.8, 27.2, 26.3. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C23H24N3O4 [M + H]+: 406.1767 found: 406.1759.

Compound 20.29

To the cooled (−30 °C) mixture of 3-amino-propionaldehyde diethylacetal (11.7 g, 79.6 mmol) and TEA (8.8 g, 12.2 mL, 87.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (125 mL) a solution of AcCl (6.9 g, 6.3 mL, 87.9 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added dropwise. Reaction was carried out 1 h at −30 °C, followed by addition of H2O (50 mL). Organic layer was separated, dried over MgSO4, and after filtration and evaporation colorless oil of N-(3,3-diethoxypropyl)acetamide was obtained (13.4 g, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=6.27 (br s, 1H, NHCO), 4.51 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.66-3.59 (m, 2H), 3.49-3.41 (m, 2H), 3.31-3.27 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.79-1.75 (m, 2H), 1.18-1.14 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 169.8, 102.3, 61.8, 35.5, 32.8, 23.2, 15.2. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C9H19NO3Na [M + Na]+: 212,1263 found: 212.1254. Crude N-(3,3-diethoxypropyl)acetamide was sufficiently pure and was used for the synthesis of 20 without further purification. The mixture of N-(3,3-diethoxypropyl)acetamide (1 g, 5.3 mmol) in 0.6 M HClaq. in dioxane (4 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 2.5 h (TLC monitored). After careful evaporation of the reaction mixture crude aldehyde 20 was immediately used for the next step without further purification.

Compound 21

To the mixture of 20 (547 mg, 4.7 mmol) and 19 (1.93 g, 4.7 mmol) in C2H4Cl2 (40 mL), NaBH(OAc)3 (1.21 g, 5.7 mmol) was added. Reaction was carried out for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with H2O (50 mL). Organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and after filtration and evaporation yellowish oil was obtained (1.85 g, 77%). Crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel; 27:2:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH:NH3aq.). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.77-7.73 (m, 4H), 7.67-7.62 (m, 4H), 6.88 (br t, 1H, NHCO), 3.66-3.60 (m, 4H), 3.26-3.22 (m, 2H), 2.41-2.35 (m, 6H), 1.92 (s, 3H), 1.77-1.70 (m, 2H), 1.66-1.56 (m, 4H), 1.45-1.37 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 170.1, 168.2, 168.19, 133.8, 133.7, 123.0, 53.0, 51.8, 51.4, 38.3, 37.6, 36.1, 26.3, 26.12, 26.1, 24.0, 23.1. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C28H33N4O5 [M + H]+: 505.2451 found: 505.2443.

N4-(N-Acetylaminopropyl)spermidine Trihydrochloride (22 × 3HCl)

The mixture of 21 (1.3 g, 2.6 mmol) and hydrazine hydrate (387 mg, 7.8 mmol) in EtOH (30 mL) was stirred under reflux for 4 h, and then the solution (2.6 mL of HClconc. in 10 mL EtOH) was added. After 30 min of stirring under reflux, reaction was cooled to room temperature and evaporated. The residue was dissolved in H2O (30 mL), filtrated and supernatant liquid was evaporated. Consecutively the residue was dissolved in H2O (10 mL), filtrated and supernatant liquid was evaporated. Finally the residue was dissolved in small amount of H2O (3 mL) cooled to 5 °C, filtrated through Celite and evaporated under high vacuum to give product as yellowish very hygroscopic solid (733 mg, 80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ = 3.13-3.02 (m, 8H), 2.93-2.85 (m, 4H), 1.98-1.88 (m, 2H), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.78-1.72 (m, 2H); 1.67-1.51 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δ = 174.7, 52.4, 50.8, 49.9, 38.9, 36.6, 36.4, 24.0, 23.4, 22.0, 21.7, 20.6. ESI HR (MeOH) calcd for C12H29N4O [M + H]+: 245.2341 found: 245.2339.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from Department of Energy (DE-FG0207ER64325 and DE-AC0205CH11231) and the National Institutes of Health (P30 MH062261 and R24 EY017540).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

1D and 2D NMR spectra are available for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wikoff WR, Pendyala G, Siuzdak G, Fox HS. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2661–2669. doi: 10.1172/JCI34138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Want EJ, Nordstrom A, Morita H, Siuzdak G. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:459–468. doi: 10.1021/pr060505+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabor CW, Tabor H. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SS. A Guide to the Polyamines. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards ML, Prakash NJ, Stemerick DM, Sunkara SP, Bitonti AJ, Davis GF, Dumont JA, Bey P. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:1369–1375. doi: 10.1021/jm00167a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saab NH, West EE, Bieszk NC, Preuss ChV, Mank AR, Casero RA, Woster PM. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2998–3004. doi: 10.1021/jm00072a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y, Hager ER, Phillips DL, Dunn VR, Hacker A, Frydman B, Kink JA, Valasinas AL, Reddy VK, Marton LJ, Casero R, Jr, Davidson NE. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:2769–2777. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basuroy UK, Gerner EW. J. Biochem. 2006;139:27–33. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geall AJ, Baugh JA, Loyevsky M, Gordeuk VR, Al-Abed Y, Bucala R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1161–1165. doi: 10.1021/bc0499578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodnow R, Jr, Konno K, Niwa M, Kallimopoulos T, Bukownik R, Lenares D, Nakanishi K. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:3267–3286. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang F, Manku S, Hall DG. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1581–1583. doi: 10.1021/ol005817b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kromann H, Krikstolaityte S, Andersen AJ, Andersen K, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Jaroszewski JW, Egebjerg J, Strømgaard K. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5745–5754. doi: 10.1021/jm020314s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshima T. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:8720–8722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terui Y, Ohnuma M, Hiraga K, Kawashima E, Oshima T. Biochem. J. 2005;388:427–433. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshima T. Amino Acids. 2007;33:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0526-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trauger SA, Kalisiak E, Kalisiak J, Morita H, Weinberg MV, Menon AL, Poole FL, II, Adams MWW, Siuzdak G. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:1027–1035. doi: 10.1021/pr700609j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrington S, Renault J, Tomasi S, Corbel J-C, Uriac P, Blagbrough IS. Chem. Commun. 1999:1341–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chhabra SR, Khan AN, Bycroft BW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1095–1098. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strømgaard K, Bjørnsdottir I, Andersen K, Brierley MJ, Rizoli S, Eldursi N, Mellor IR, Usherwood PNR, Hansen SH, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Jaroszewski JW. Chirality. 2000;12:93–102. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(2000)12:2<93::AID-CHIR6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chantrapromma K, McManis JS, Ganem B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:2475–2476. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley J-C, Vigneron J-P, Lehn J-M. Synth. Commun. 1997;27:2833–2845. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tice CM, Ganem B. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:2106–2108. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chantrapromma K, McManis JS, Ganem B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:2605–2608. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganem B. Acc. Chem. Res. 1982;15:290–298. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popaj K, Guggisberg A, Hesse M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2001;84:797–816. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niitsu M, Samejima K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1992;40:2958–2961. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu W, Hesse M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1996;79:548–559. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitkul B, Bradley M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:2367–2369. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Compound 20 decomposes at room temperature, therefore crude aldehyde was immediately used in the reductive amination step without purificationBoukouvalas J, Golding BT, McCabe RW, Slaich PK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1983;22:618–619.Boukouvalas J, Golding BT, McCabe RW, Slaich PK. Angew. Chem. Suppl. 1983:860–873.

- 30.Ohnuma M, Terui Y, Tamakoshi M, Mitome H, Niitsu M, Samejima K, Kawashima E, Oshima T. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30073–30082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robb FT, Maeder DL, Brown JR, DiRuggiero J, Stump MD, Yeh RK, Weiss RB, Dunn DM. Methods Enzymol. 2001;330:134–157. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)30372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goss DJ, Parkhurst LJ, Wahba AJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:10119–10127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uzawa T, Yamagishi A, Ueda T, Chikazumi N, Watanabe K, Oshima T. J. Biochem. 1993;114:732–734. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila-Sanjurjo A, Schuwirth BS, Hau CW, Cate JH. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nsmb850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao X, Antony S, Kohlhagen G, Pommier Y, Cushman M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:5147–5160. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]