Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To conduct a population-based study to assess health care utilization (HCU) and costs associated with herpes zoster (HZ) and its complications, including postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) and nonpain complications, in adults aged 22 years and older.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Medical record data on HCU were abstracted for all confirmed new cases of HZ from January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2001, among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. Herpes zoster-related costs were estimated by applying the Medicare Payment Fee Schedule to health care encounters and mean wholesale prices to medications. All costs were adjusted to 2006 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

RESULTS: The HCU and cost of the 1669 incident HZ cases varied, depending on the complications involved. From 3 weeks before to 1 year after initial diagnosis, there were a mean of 1.8 outpatient visits and 3.1 prescribed medications at a cost of $720 for cases without PHN or nonpain complications compared with 7.5 outpatient visits and 14.7 prescribed medications at a cost of $3998 when complications, PHN, or nonpain complications were present.

CONCLUSION: The annual medical care cost of treating incident HZ cases in the United States, extrapolated from the results of this study in Olmsted County, is estimated at $1.1 billion. Most of the costs are for the care of immunocompetent adults with HZ, especially among those 50 years and older.

The annual medical care cost of treating incident cases of herpes zoster and its complications in the United States, extrapolated from the results of this population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, is estimated to be $1.1 billion. Most of the costs are for the care of immunocompetent adults with herpes zoster, especially those 50 years and older.

ED = emergency department; HCU = health care utilization; HZ = herpes zoster; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; PHN = postherpetic neuralgia; REP = Rochester Epidemiology Project

Nearly 1 million new cases of herpes zoster (HZ) occur annually in the United States.1,2 Herpes zoster results from reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which remains dormant after infection with chickenpox. Declining cellular immunity associated with aging and immunocompromising conditions increase the risk of HZ and HZ complications.3-5 However, most HZ cases (>90%) occur in immunocompetent people.1,2 Herpes zoster can adversely affect a person's health-related quality of life6-8 because of complications such as eye and other nonpain complications 2 as well as acute and chronic pain (postherpetic neuralgia [PHN]) that can result in severe activity limitations and sleep disturbances.2,6,9

Claims data have been used to estimate the health care utilization (HCU) and cost of HZ in the United States.10,11 However, such data have potential limitations. Claims data may not capture all the HCU and costs attributable to the complications of HZ, including PHN and nonpain complications. In the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM),12 few HZ complication-specific diagnostic codes are available, and they may not be used reliably. Although there is an ICD-9-CM diagnostic code for PHN, there is no standard definition for PHN that is used by all physicians. In addition, not all HZ-related visits are coded with a zoster-specific diagnostic code, especially visits that occur before definitive diagnosis. Medications, laboratory tests, and procedures are not directly linked to disease codes, making attribution to HZ difficult.13 Coding errors and the use of codes to refer to differential diagnoses may also result in incorrectly assigning claims to HZ.2

We present data on medical care for HZ from a retrospective, population-based study of all Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents aged 22 years and older who were diagnosed by a physician as having a new episode of HZ from January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2001. The HCU data were collected through an extensive review of medical records to overcome some of the problems encountered when using claims data to attribute HCU to HZ. This work provides a comprehensive assessment of the HCU and economic burden of HZ in a community setting.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Source of Data

Olmsted County provides a unique setting for population-based studies by allowing all county residents' medical care to be followed up across all health care systems within the county. All patients have visit-specific records kept within their care facility, and visit-specific diagnostic and procedure codes are warehoused within the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) database.14-16 We searched the REP database for all patients who were residents of Olmsted County and who had a diagnostic code related to HZ in 1996 through 2001. For verified incident HZ cases, selected patient characteristics, clinical details about the manifestations and the duration of the episode including all HZ complications, and the HCU required to treat the infection were abstracted. A more detailed description of the health care system in Olmsted County and the definitions of HZ, immunocompromising conditions, PHN, and the classification of other HZ complications by type used in this study have been previously published.2

HCU Data Abstracted

Data were collected for a period of 3 weeks before the definitive HZ diagnosis until at least 1 year after diagnosis. Health care encounters included hospital admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient care in a variety of settings, including visits to primary care physicians, specialists, urgent care centers, and outpatient facilities in hospitals. Health care utilization was attributed to HZ if HZ problems or therapy modification was mentioned in the medical notes, HZ pain medication was prescribed, or other therapy for HZ was initiated even if the final coded diagnoses did not list HZ as the first code. Data on medications were collected from prescription data, each individual medication being referred to as a prescribed medication. In the 21 days before the HZ diagnosis, HCU was attributed to HZ if the reason for the visit was symptoms at the site of the HZ episode eventually diagnosed and if those symptoms were not attributed to some other condition after HZ was diagnosed. Of note, ocular complications were defined as conditions that involved the globe of the eye, such as iritis, uveitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis, or loss of vision, but did not include rashes around the eye. Every hospitalization was reviewed by the lead investigator (B.P.Y.) to determine whether HZ was the reason for hospitalization. The duration of hospitalization due to HZ was also determined. Given that a number of nurses were involved in abstracting the data, procedures were instituted to ensure high inter-rater reliability.2

Cost Data

Costs were estimated from the first 3 weeks before initial diagnosis until 90 days (referred to as the acute phase) and until 1 year after initial diagnosis. Standardized costs were applied to each type of service provided. The costs for health care encounters, diagnostic tests, and procedures were based on the Medicare Payment Fee Schedule. The standardized costs of medications were based on the mean wholesale price from the Red Book.17 Hospitalization costs were estimated by applying the US median value of the mean cost per patient day ($1766) to the mean length of stay found in the study.18 The ED and hospital outpatient visit costs were based on zoster-specific mean payments reported in Medstat.10 The cost applied to the outpatient visits in Olmsted County reflects a weighted mean of Medicare payments.18 A range of Medicare payments is assigned to an outpatient visit, depending on the intensity or duration of the visit, the type of health care professional involved, and whether the visit was for a new or established patient. The distribution of initial vs follow-up visits in this study was based on review of the medical records and distribution of visits for new vs established patients, and type of specialty was based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2003 Summary.11

Unit costs of medication differ by manufacturer, purchaser, and route of administration. Therefore, we used data on the type of medication and route of administration for each medication and then chose 1 of the manufacturers of that medication with the lowest unit costs for that route of administration. All costs were adjusted to 2006 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Study Populations, Duration of Follow-up, and Methods Applied

The mean number of health care encounters by type, diagnostic tests, procedures, and prescribed medications and the mean cost of each service provided are presented along with the standard errors of the estimates for all patients with HZ and stratified by immune status, type of complication, and age. For each analysis, the results are presented from the first 3 weeks before initial diagnosis until 90 days (acute phase) and 1 year after initial diagnosis.

RESULTS

Summary of Study Population

Of the 2131 potential HZ cases among patients 22 years or older identified in the Olmsted County REP database, 462 were excluded from the study, 172 for administrative reasons and 290 for clinical reasons. Administrative reasons were as follows: patients were not residents of Olmsted County at the time of diagnosis (n=137), HZ diagnosis occurred beyond the study window (n=7), condition diagnosed outside Olmsted County with no specifics (n=12), and research refusal (n=16). The reasons for clinical exclusions were as follows: only “history of HZ” in the clinical notes (n=111), laboratory evidence of herpes simplex but coded as HZ (n=84), HZ was only part of a differential diagnosis but not the final diagnosis (n=77), no HZ-related events (presumed miscoded) (n=13), and acute varicella (n=5).2 There were 1669 confirmed new HZ cases among Olmsted County residents from January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2001, including 139 cases in immunocompromised patients (8%), 171 cases in patients with HZ pain for at least 90 days defined as PHN (10%), and 159 cases in patients with HZ complications other than PHN (10%), further referred to as nonpain complications. These nonpain complications included ocular complications in 68 patients (4%), neurologic complications in 54 (3%), dermatological complications in 27 (2%), and other complications, such as disseminated HZ or encephalitis, in 26 (2%). Thirteen patients (1%) had more than 1 nonpain complication, and 48 (3%) had both PHN and 1 or more nonpain complications. For the cohorts of patients with PHN or nonpain complications, the HCU and costs reported reflect all HZ-related care for these patients, rather than only the care for these specific complications after development.

HZ-Attributable HCU and Costs

Patients mainly had HZ diagnosed and treated in the outpatient setting. Among the 1669 incident cases of HZ, the cost was $346 for a mean number of 2.8 outpatient visits and was $436 for a mean number of 5.1 prescribed medications from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis. There were 66 HZ-related hospitalizations, with a mean length of stay of 5.1 days. From 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis, the mean cost of HZ was $1273, of which 29.3% was for hospitalizations. The number of outpatient visits and prescribed medications and the percentage of costs for inpatient care varied, depending on the presence of complications, and increased with age.

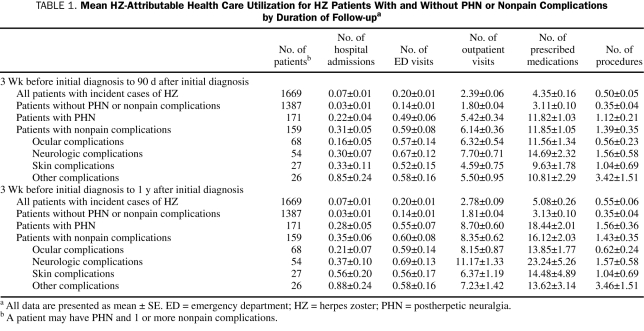

Table 1 shows that the mean number of health care encounters and prescribed medications related to HZ is higher for patients with PHN or nonpain HZ complications compared with HZ patients without PHN or nonpain complications. This finding is observed for HCU from 3 weeks before to 90 days and 1 year after diagnosis. For example, among patients without PHN or nonpain complications, the mean ± SE number of outpatient visits was 1.81±0.04, and the mean ± SE number of prescribed medications was 3.13±0.10 from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis. By comparison, the mean ± SE number of outpatient visits among the subgroup with PHN was 8.70±0.60, and the mean ± SE number of prescribed medications was 18.44±2.01. For those with nonpain complications, the mean ± SE number of outpatient visits was 8.35±0.62, and the mean ± SE number of prescribed medications was 16.12±2.03. This included the 3% of patients with both nonpain complications and PHN.

TABLE 1.

Mean HZ-Attributable Health Care Utilization for HZ Patients With and Without PHN or Nonpain Complications by Duration of Follow-upa

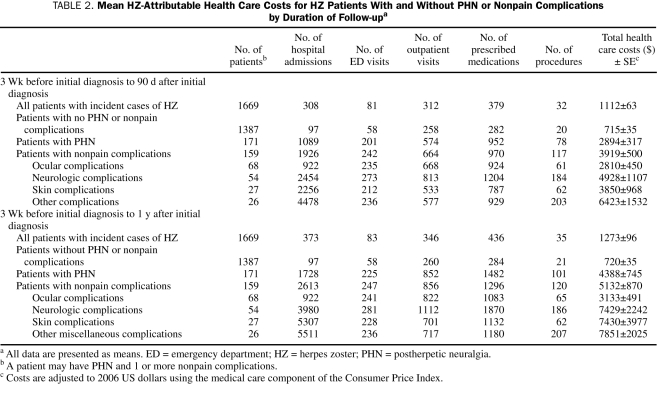

As shown in Table 2, from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis, the mean ± SE cost to treat HZ patients without PHN or nonpain complications was $720±$35 compared with $4388±$745 for HZ patients with PHN and $5132±$870 for HZ patients with nonpain complications. The mean ± SE cost of nonpain complications ranged from $3133±$491 for HZ patients with ocular complications to $7851±$2025 for those with complications such as disseminated zoster. Among HZ patients without PHN or nonpain complications, inpatient hospitalizations accounted for only 13.5% of the mean cost per case compared with 39.4% and 50.9% of the mean cost of treating PHN and nonpain complications, respectively. Among those without PHN or nonpain complications, nearly all the costs were incurred 3 weeks before to 90 days after diagnosis. This period accounts for 66.0% of the costs of caring for those with PHN but 76.4% of the costs (P<.001) for those with only nonpain complications.

TABLE 2.

Mean HZ-Attributable Health Care Costs for HZ Patients With and Without PHN or Nonpain Complications by Duration of Follow-upa

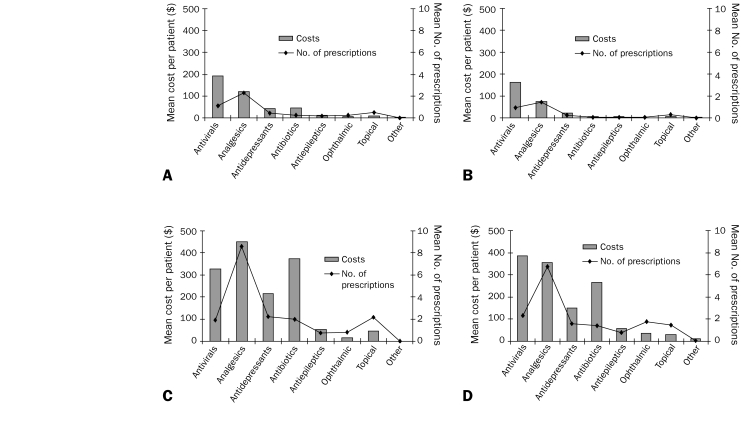

The difference in the cost of treating HZ for patients with and without PHN or nonpain complications also in part depended on the number of prescribed medications over time. The most common therapeutic categories involved in the treatment of HZ were antivirals, analgesics, antiepileptics, and antidepressants. Other types of less frequently prescribed medications included topical agents, antibiotics, and ophthalmologic products. Figure 1 provides the mean medication cost by therapeutic category for HZ patients with and without PHN or nonpain complications. For HZ patients without PHN or nonpain complications, the mean number of prescribed medications included 0.97 for antivirals, 1.40 for analgesics, 0.22 for antidepressants, and 0.04 for antiepileptics, at a mean cost of $284. For HZ patients with PHN, the mean number of prescribed medications included 1.94 for antivirals, 8.58 for analgesics, 2.25 for antidepressants, and 1.99 for antiepileptics, at a mean cost of $1482. For HZ patients with nonpain complications, the mean number of prescribed medications included 2.31 for antivirals, 6.74 for analgesics, 1.58 for antidepressants, and 1.42 for antiepileptics, at a mean cost of $1296.

FIGURE 1.

Medication cost by type for all patients with herpes zoster (HZ) (A), HZ patients without postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) or nonpain complications (B), HZ patients with PHN (C), and HZ patients with nonpain complications (D) from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis.

HZ-Attributable HCU and Costs Stratified by Age for HZ Patients With and Without PHN or Nonpain Complications

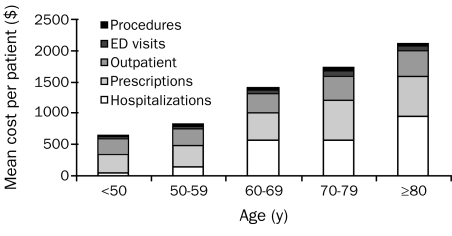

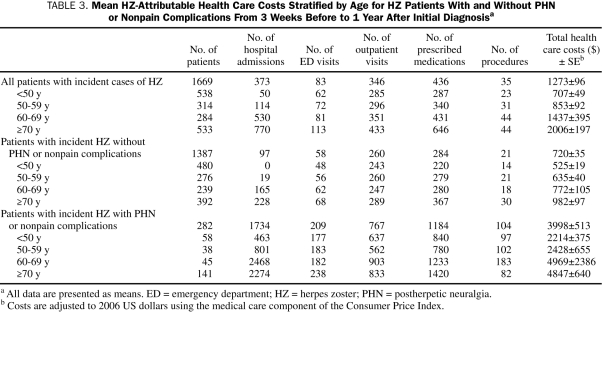

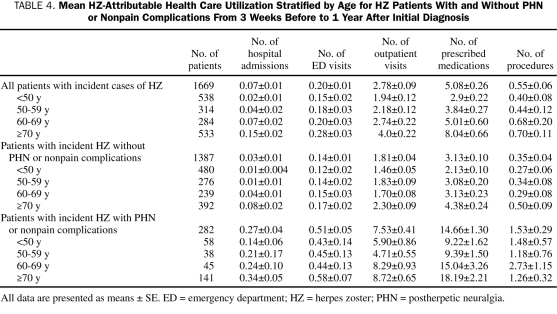

As shown in Figure 2, the overall cost of treating HZ patients and the proportion of the cost attributable to hospitalizations increase with age. The mean ± SE cost per incident HZ case among those younger than 50 years was $707±$49 and increased to $2006±$197 among those 70 years or older (Table 3). For patients younger than 50 years, hospitalizations represented 7.1% of the cost compared with 38.4% of the cost for those 70 years or older. The mean number of health care encounters for hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, and prescribed medications all increased with age (Table 4). The increase in HCU and cost by age was in part due to the increase in the rate of PHN and nonpain complications by age. Ninety-eight (57.3%) of patients with PHN and 71 (44.7%) of those with nonpain complications were 70 years or older. However, the cost of treating HZ without PHN or nonpain complications also increased with age from $525±$19 among those younger than 50 years to $982±$97 among those 70 years or older. The increase with age for HZ patients without PHN or nonpain complications was also observed for hospitalization costs.

FIGURE 2.

Mean costs per herpes zoster patient by age and type of health care resource from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis. ED = emergency department.

TABLE 3.

Mean HZ-Attributable Health Care Costs Stratified by Age for HZ Patients With and Without PHN or Nonpain Complications From 3 Weeks Before to 1 Year After Initial Diagnosisa

TABLE 4.

Mean HZ-Attributable Health Care Utilization Stratified by Age for HZ Patients With and Without PHN or Nonpain Complications From 3 Weeks Before to 1 Year After Initial Diagnosis

HZ-Attributable HCU and Cost Stratified by Immune Status

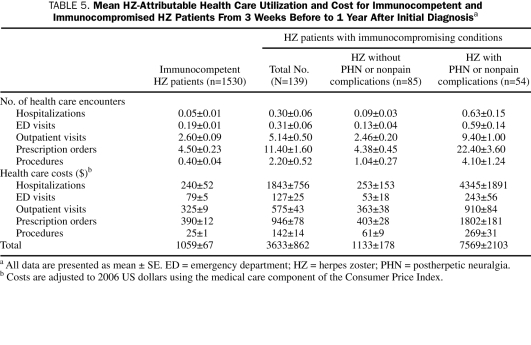

Overall, 76.2% of the HZ-related costs were for immunocompetent adults. However, patients with immunocompromising conditions had higher mean costs because of the higher rates of PHN and nonpain complications in this group.2 As indicated in Table 5, among those defined as immunocompetent, the mean ± SE cost was $1059±$67 from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis. By comparison, the mean ± SE cost for those with immunocompromising conditions was $3633±$862 for the same period. This is in part due to the higher rates of PHN and nonpain complications among immunocompromised HZ patients. Of the 139 HZ patients with immunocompromising conditions, 54 (39%) experienced 1 or more of these complications. The mean ± SE cost of HZ for patients with immunocompromising conditions experiencing PHN or nonpain complications was $7569±$2103 compared with $1133±$178 for those without PHN or nonpain complications.

TABLE 5.

Mean HZ-Attributable Health Care Utilization and Cost for Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised HZ Patients From 3 Weeks Before to 1 Year After Initial Diagnosisa

DISCUSSION

The results of the current study suggest that reliance on claims data may not capture all the HCU and costs associated with PHN and nonpain complications related to HZ. Both Yawn et al2 and Insinga et al10 estimated that 1 million new episodes of HZ occur each year in the United States. However, the mean HZ-related health care cost per case beginning 3 weeks before diagnosis through 90 days after diagnosis was $1112 using medical record data compared with the estimate of $431 reported by Insinga et al using US claims data. Both studies demonstrated that the mean cost increased with age, but in the study by Yawn et al,2 the mean cost ranged from $661 for those younger than 50 years to $2009 for those 80 years or older. By comparison, the mean cost from 3 weeks before to the first 90 days after diagnosis was less than $400 for those younger than 50 years in the study by Insinga et al and increased to only $805 among those 80 years or older. We speculate that the difference in results between the study by Insinga et al and the current review of medical records relates to the difficulty in identifying all HZ-related HCU with ICD-9-CM codes for new cases of HZ in a claims database. The estimate of the mean cost of PHN from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis in the current study was $4388, which is consistent with the results from the study by Dworkin et al,19 in which the estimates for PHN ranged from $2159 to $5742, depending on the type of insurance and the way in which PHN was defined. Dworkin et al noted that as many as 80% of patients with PHN may not have a PHN diagnosis coded in the administrative or billing codes and that these patients account for at least half of PHN expenditures. To compensate for this, Dworkin et al identified PHN based on a diagnosis of HZ with use of analgesics for more than 30 days after HZ diagnosis; however, the sensitivity and specificity of this approach to defining PHN were not established, and the cost estimates were sensitive to the type of analgesics included. In the current study, we also found that many patients with PHN had no visit code for PHN, especially after the first few visits. Postherpetic neuralgia was identified on the basis of reports of continued pain at the HZ site and prescriptions for pain medications (including antiepileptics and antidepressants) that continued more than 90 days after the HZ diagnosis. Moreover, we included the few people who had pain-relief procedures, such as nerve blocks, for continuing pain at the site of the HZ.

The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to describe the HCU and mean costs for complications of HZ other than PHN. The study found that the mean cost from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis of HZ of $5132 for treating these nonpain complications is comparable to that for treating PHN. The substantially higher costs of treating PHN or nonpain complications compared with a mean cost of $720 for patients without PHN or nonpain complications from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis does not simply reflect a longer duration of illness. Even in the acute phase of HZ, from 3 weeks before to 90 days after diagnosis, the cost of treating PHN or nonpain complications far exceeds the cost of treating patients with no such complications. In that period, the mean cost of treating patients with PHN is $2894 and the mean cost of treating HZ patients with nonpain complications is $3919 compared with $715 for patients without PHN or nonpain complications. Thus, a substantial percentage of the costs of treating HZ complications occur within the first 90 days after diagnosis. These results support the theory that people who ultimately develop PHN may experience prodromal pain or more severe pain soon after diagnosis.3,8,20

For those without PHN or nonpain complications, outpatient visits and prescription drugs contribute the most to the cost of treating HZ. For patients with PHN or nonpain complications, hospitalizations represent a much higher percentage of the overall cost. For those with no PHN or nonpain complications, hospitalizations represented only 13.5% of the cost from 3 weeks before to 1 year after diagnosis. By comparison, hospitalizations represented 39.4% of the total cost for PHN complications and 50.9% of the total cost for nonpain complications. Most HZ-related hospitalizations did not involve immunocompromised patients. Although HZ patients with immunocompromising conditions were often admitted for intravenous administration of antiviral therapy, in general, the most common reasons for hospitalization of patients with HZ were dehydration and pain management in elderly patients (≥70 years).

Our finding of a higher risk of PHN and nonpain complications among elderly patients and those with immunocompromising conditions is consistent with earlier studies.2,5,7,10 The higher risk of PHN or nonpain complications contributes to the higher cost of treating HZ in these subgroups. However, the cost of treating patients with HZ without PHN or nonpain complications among those 70 years or older and patients with immunocompromising conditions is also higher compared with the overall mean cost of treating patients without PHN or nonpain complications. This finding reflects that a patients's overall health status and presence of comorbid conditions may impede that person's ability to recover from the illness. In addition, patients with a number of comorbid conditions may be treated more conservatively by physicians.

The current study has a number of limitations. The data were collected retrospectively. Thus, some of the care associated with the treatment of HZ may have been missed, and only care documented in the medical records was captured. This likely resulted in an underestimate of true HZ-related HCU and costs. In addition, only a small number of patients with nonpain complications were identified, which resulted in a high degree of variability for some of the cost estimates. Finally, we could capture only the prescriptions ordered by the physician, and these prescriptions may not have been filled. However, the study suggests that claims data may not capture all the HCU and costs associated with PHN and nonpain complications. Greater awareness of the burden of HZ and its complications is critical in assessing the cost-effectiveness of treatment of HZ and prevention through vaccination.

CONCLUSION

Herpes zoster is a common condition, and nearly 20% to 25% of HZ patients experience 1 or more complications, including PHN or other nonpain complications. Any type of complication more than triples the cost of HZ-related care. The medical care cost of treating incident HZ cases in the United States, extrapolated from the results of the current study, is estimated at $1.1 billion annually. Although people with immunocompromising conditions are more likely to have PHN or other nonpain complications and to be hospitalized for HZ, most HZ costs occur in those who are immunocompetent, especially in patients 50 years and older.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the help of Dawn Littlefield, BS, in preparation of the submitted manuscript and Melissa Whipple-Neibauer, MS, for her technical and scientific support.

Footnotes

This work was funded by grants from Merck Research Laboratories, North Wales, PA, and the National Institutes of Health (AR30582).

REFERENCES

- 1.Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JP, Saddier P, Nikas AA. The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):748-753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. Population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction [published correction appears in Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(2):255] Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(11):1341-1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choo PW, Galil K, Donahue JG, Walker AM, Spiegelman D, Platt R. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(11):1217-1224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galil K, Choo PW, Donahue JG, Platt R. The sequelae of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1997;1579(11):1209-1213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvin A. Aging, immunity, and the varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2266-2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995;45(12, suppl 8):S52-S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmader KE. Epidemiology and impact on quality of life of postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy. Clin J Pain 2002;18(6):350-354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmader KE, Sloane R, Pieper C, et al. The impact of acute herpes zoster pain and discomfort on functional status and quality of life in older adults. Clin J Pain 2007;23(6):490-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnann JW, Jr, Whitley RJ. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):340-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM. Acute/subacute herpes zoster. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25(2):155-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics Vital and Health Statistics: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2003 Summary Hyattsville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Clinical Modification Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(15):1605-1609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(3):266-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245(4):54-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yawn BP, Yawn RA, Geier GR, Xia A, Jacobsen SJ. The impact of requiring patient authorization for use of data in medical records research. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(5):361-365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2006 Red Book: Pharmacy' Fundamental Reference Montvale, NJ: Thompson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleavery and Associates 2006 US median value of the mean hospital cost per day; http://www.stats.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf Accessed on August 18, 2008

- 19.Dworkin RH, White R, O'Connor AB, Baser O, Hawkins K. Healthcare costs of acute and chronic pain associated with ad of herpes zoster. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1168-1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmader K, George LK, Burcett BM, Pieper C. Racial and psychosocial risk factors for herpes zoster in the elderly. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(suppl 1):S67-S70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.