Abstract

Fos and Jun are components of activator protein-1 (AP-1) and play crucial roles in the regulation of many cellular, developmental, and physiological processes. Caenorhabditis elegans fos-1 has been shown to act in uterine and vulval development. Here, we provide evidence that C. elegans fos-1 and jun-1 control ovulation, a tightly regulated rhythmic program in animals. Knockdown of fos-1 or jun-1 blocks dilation of the distal spermathecal valve, a critical step for the entry of mature oocytes into the spermatheca for fertilization. Furthermore, fos-1 and jun-1 regulate the spermathecal-specific expression of plc-1, a gene that encodes a phospholipase C (PLC) isozyme that is rate-limiting for inositol triphosphate production and ovulation, and overexpression of PLC-1 rescues the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms. Unlike fos-1, regulation of ovulation by jun-1 requires genetic interactions with eri-1 and lin-15B, which are involved in the RNA interference pathway and chromatin remodeling, respectively. At least two isoforms of jun-1 are coexpressed with fos-1b in the spermatheca, and different AP-1 dimers formed between these isoforms have distinct effects on the activation of a reporter gene. These findings uncover a novel role for FOS-1 and JUN-1 in the reproductive system and establish C. elegans as a model for studying AP-1 dimerization.

INTRODUCTION

Ovulation is a tightly regulated rhythmic program. Because the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is transparent and genetically tractable, it has become a model for studying this program. In C. elegans, an ovulation cycle begins as sperm signal the most proximal oocyte (the −1 oocyte) to mature. A critical component of this signal is major sperm protein (MSP), which binds the VAB-1 Eph receptor protein tyrosine kinase on oocytes and sheath cells (Miller et al., 2001, 2003). The MSP signal promotes oocyte maturation and sheath cell contractions. The oocyte then undergoes nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) and cortical rearrangement, and signals sheath cells via the epidermal growth factor-like ligand, LIN-3, to increase the strength and frequency of their contractions. When these contractions are coupled with dilation of the distal spermathecal valve, the mature oocyte is ovulated into the spermatheca for fertilization (McCarter et al., 1997, 1999). After fertilization, the spermatheca-uterine valve dilates so that the new egg can pass into the uterus (Figure 1A).

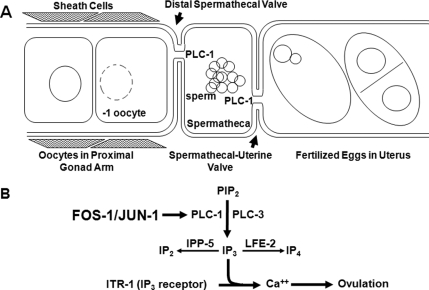

Figure 1.

Regulation of ovulation by IP3 signaling. (A) Outline of ovulation control in C. elegans. Ovulation is coordinated by sheath cell contractions and distal spermathecal valve dilation. These steps are controlled by the rate-limiting enzymes PLC-3 and PLC-1, respectively, which produce IP3, thereby causing an increase in calcium concentration. (B) Genetic regulation of IP3 concentration in sheath cells and spermathecal cells. This study demonstrates that C. elegans FOS-1 and JUN-1 regulate PLC-1 expression in the spermatheca and control distal spermathecal valve dilation.

Genetic analyses revealed that the inositol triphosphate (IP3) signaling pathway plays a critical role in ovulation, because sheath cell contractions, distal spermathecal valve dilation, and spermatheca-uterine valve dilation are all controlled by IP3-induced calcium release (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004) (Figure 1B). IP3 is produced in sheath cells and spermathecal cells by the catalytic activity of the phospholipase C (PLC) enzymes PLC-3, PLC-1, or both. Levels of IP3 can be reduced by IP3 kinase let-23 fertility effector/regulator (LFE-2) or type I polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (IPP-5) (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). Thus, loss-of-function mutations in lfe-2 or ipp-5 increase IP3 concentration and suppress the ovulation defect caused by lin-3 mutations (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002). In addition, a gain-of-function mutation in itr-1, the IP3 receptor, sensitizes it to Ca2+, which also rescues the ovulation defects caused by mutants for the LIN-3 signal (Clandinin et al., 1998).

Fos and Jun are members of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family, which constitutes an important subset of basic region leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (Karin et al., 1997; Wagner, 2001). AP-1 proteins function as homodimers or heterodimers that bind DNA and regulate transcription of target genes. Genetic and biochemical studies have demonstrated that AP-1 proteins are critical regulators of many cellular and developmental processes, including growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress responses (Karin et al., 1997).

Recent studies in C. elegans showed that FOS-1A, one of the two isoforms of the C. elegans Fos homologue, regulates the development of the reproductive system, including anchor cell invasion and development of the uterus (Sherwood et al., 2005; Oommen and Newman, 2007). However, knockdown of fos-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) or deletion of fos-1 also causes sterility (Oommen and Newman, 2007), which implies that fos-1 plays additional roles in reproduction. Here, we show that FOS-1B regulates spermathecal valve dilation by controlling plc-1 expression (Figure 1B). We also demonstrate that the C. elegans Jun homologue participates in this process. However, JUN-1 has a milder phenotype, and genetic evidence suggests that its role in ovulation is influenced by mutations in genes involved in the RNAi pathway and chromatin remodeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

Some nematode and Escherichia coli strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources. These reagents include OP50 and HT115(DE3) Escherichia coli, and the following nematode strains: wild-type N2, SU93 (ajm-1::gfp), NL2098 rrf-1(pk1417) I, NL2099 rrf-3(pk1426) II, KP3948 eri-1(mg366) IV; lin-15B(n744) X, PS2286 unc-38(x20); lfe-2(sy326) I, ZZ20 unc-38(x20) I, PK2368 itr-1(sy327); unc-24(e138) IV, CB138 unc-24(e138) IV, PS3653 ipp-5(sy605) X, VC1200 jun-1(gk557), and PD8120 smg-1(cc546) I. ipp-5::gfp, plc-3::gfp and two itr-1::gfp strains were kindly provided by P. Sternberg (California Institute of Technology), K. Strange (Vanderbilt University), and H. Baylis (University of Cambridge), respectively.

Feeding RNAi

cDNAs encoding the bZIP region of fos-1 and jun-1, full-length fog-3, exons 1 through 4 of unc-112, exons 1-7 of eri-1a, and the first 1 kb of the 5′ end of lin-15B were cloned into the feeding RNAi vector pPD129.36 (Timmons and Fire, 1998). Feeding RNAi was performed as described previously (Kamath et al., 2001). In brief, HT115(DE3) E. coli were transformed with plasmid and grown 8 h at 37°C in Luria Broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and tetracycline (15 μg/ml). RNAi plates containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml), tetracycline (15 μg/ml), and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (1 mM) were seeded with 200 μl of bacteria and incubated at 37°C overnight. Adult N2 worms were added and allowed to lay eggs for 48 h at 20°C. Phenotypes of F1 progeny were scored after an additional 24–48 h. eri-1;lin-15B worms were allowed to lay eggs for 72 h or were not removed until analysis of offspring.

Genetic Interactions between jun-1 and eri-1 or lin-15B

The homozygous double mutant jun-1(gk557);lin-15B(n744) X was made and confirmed by genotyping with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). RNAi in the background of various strains was performed as described above. Sterility was defined as the absence of fertilized eggs in the uterus.

4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) Staining

Fixation and staining were performed as described previously (Francis et al., 1995), with slight modifications. In brief, a 60-mm plate of worms was rinsed twice with M9 buffer and then fixed in 3% fresh paraformaldehyde for 1 h. After two washes with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), worms were fixed in cold methanol at −20°C for 10 min. After two additional PBST washes, samples were incubated with 100 ng/ml DAPI in PBST for 10 min, washed, and mounted on slides. Images were captured using a Photometrics CoolSNAP ES digital camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ) controlled by MetaMorph version 6.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) by using DAPI filters from Chroma Technology (Brattleboro, VT).

Time-Lapse Analysis of First Ovulations

Sheath cell contractions and spermathecal valve dilation studies were performed as described previously (Yin et al., 2004). In brief, vector control or RNAi-treated adult worms were anesthetized in tricaine (0.1%) and tetramisole (0.01%) in M9 for 30–50 min. Worms were examined as described above, and images were acquired once per second for up to 45 min total. Time zero for each image was set to the completion of entry of the oocyte into the spermatheca. Ovulatory contractions consisted of the average contractions per minute of the three minutes preceding entry of the oocyte (−3 to −1). Basal contractions were averaged from 10 to 5 min before ovulation (−10 to −5). For fos-1(RNAi) worms, ovulatory contractions are maximal sheath contractions at the time of oocyte maturation, as evidenced by NEBD and cortical rearrangement. This “rounding” effect is consistent with that seen in the −3 to −1 time point for vector-treated worms. Contractions in each one minute time frame were counted at least three times and averaged.

Effect of fos-1 and jun-1 RNAi on plc-1:: gfp Expression in the Spermatheca

RNAi was performed as described above using the transgenic line expressing a plc-1::gfp reporter as described previously (Kariya et al., 2004). To quantify fluorescence intensity in the spermatheca of young adult F1 worms, regions of interest (average, 11.4) were selected in each spermatheca, and the average fluorescence intensity was calculated (average, 7.2 spermathecae per RNAi treatment) using microscopy setup described above with green fluorescent protein (GFP) filters. A Student's t test was used to compare average fluorescence intensities between samples and to determine statistical significance.

Isolation of fos-1(km30) Deletion Mutant

The deletion mutant fos-1(km30) was generated by TMP/UV (Gengyo-Ando and Mitani, 2000) and isolated using sib-selection. Screening was performed using gene-specific primers as follows: external left, 5′-GTAAGCCAAATAGGAAAATTACGGT-3′; external right, 5′-CTCGATTTTTGGAATCTGAAGTAAA-3′; internal left, 5′-TAATTTACATTAGGTTTGCCGACAT-3′; and internal right, 5′-AAATGAATGTACTCACTTTGCGTTC-3′.

Direct sequencing of the PCR products verified the deleted region. These deletion mutants were backcrossed more than twice to animals of a wild-type N2 background.

Expression Analysis of fos-1b and jun-1 Isoforms

Genomic DNA upstream of the transcriptional start sites of fos-1b (3.4 kb), jun-1abc (296 base pairs), jun-1d (296 base pairs), jun-1e (222 base pairs), and jun-1f (444 base pairs) were cloned into pPD95.70 (Fire lab C. elegans Vector Kit 1995 [www.addgene.org]). At least three independent transgenic lines were obtained following injection of each plasmid (10 ng/μl) and the rol-6(su1006) (100 ng/μl) marker. Observation of GFP expression and image acquisition were performed as described above.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

Reporter assays were carried out in COS-1 cells essentially the same as described previously (Liu et al., 2006), by using 0.5 μg of plasmid encoding FOS-1B, JUN-1A, and/or JUN-1D, and assayed for luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Statistical analysis of activation due to FOS-1B, JUN-1A, or both was performed using an ANOVA. Inhibition of FOS-1B and JUN-1A transactivation by JUN-1D also was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA.

Accession Numbers

National Center for Biotechnology Information accession numbers for cDNA sequences of jun-1a-f isoforms are EU553920, EU553921, EU553922, EU553923, EU553924, and EU553925, respectively.

fos-1 RNAi Phenotypes Rescued by PLC-1 Overexpression

Transgenic lines expressing a previously isolated PLC-1 (Shibatohge et al., 1998) driven under the heat shock promoter hsp-16.41 were constructed. The expressed PLC-1 protein (residues 88–1853) contains intact X, Y, C2, RA1, and RA2 domains but lacks the N-terminal 87 residues. Rescue experiments were performed exactly the same as the RNAi experiments except that when F1 worms reached the larval stage 4, they were heat shocked at 33°C for 2 h to induce the expression of PLC-1. A second 30-min heat shock was performed 12 h later, followed by phenotypic analysis. The endomitotic oocytes (Emo) phenotype was defined as the accumulation of endomitotic oocytes in the proximal gonad by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and confirmed by DAPI staining. Any worm showing Emo in one or both of the two proximal gonads was scored as Emo.

RESULTS

Knockdown of fos-1 and jun-1 Causes Sterility

In mammals, Fos and Jun are involved in multiple processes, including development, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress responses. To see whether the C. elegans homologue of Fos, fos-1, is also pleiotropic, we used feeding to perform RNAi in N2 worms (Kamath et al., 2001; Timmons et al., 2001). To knock down both isoforms of fos-1, we targeted the shared bZIP-encoding region. Knockdown of fos-1 resulted in F1 progeny with several phenotypes, including sterility (95.1%), a protruding vulva (13.8%), and exploded through the vulva (4.6%) (Table 1). These observations are consistent with results from several genome-wide RNAi screens and the analysis of fos-1(ar105), an allele that deletes only fos-1a (Kamath et al., 2003; Simmer et al., 2003; Rual et al., 2004; Sherwood et al., 2005; Oommen and Newman, 2007).

Table 1.

fos-1 and jun-1 are necessary for fertility and fos-1 functions in the soma

| Strain | RNAi treatment (n) | Ste (%) | Pvl (%) | Exp (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Vector (564) | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| N2 | fos-1 (348) | 95.1 | 13.8 | 4.6 |

| N2 | jun-1 (670) | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| N2 | fog-3 (208) | 99.0 | N.D. | N.D. |

| eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n7444) | Vector (92) | 6.5 | 4.4 | 0.0 |

| eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n7444) | fos-1 (34) | 97.1 | 94.1 | 5.9 |

| eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n7444) | jun-1 (92) | 93.5 | 35.9 | 10.9 |

| rrf-1(pk1417) | Vector (247) | 0.0 | N.D. | N.D. |

| rrf-1(pk1417) | fos-1 (140) | 11.4 | N.D. | N.D. |

| rrf-1(pk1417) | fog-3 (188) | 99.5 | N.D. | N.D. |

Exp, exploded through vulva; N.D., not determined; Pvl, protruding vulva; Ste, sterile.

Number of worms observed is in parentheses.

Like mammalian and Drosophila Fos and Jun proteins, C. elegans FOS-1 and JUN-1 form heterodimers (Hiatt et al., 2008; Shyu et al., 2008). To see whether C. elegans jun-1 has the same role as fos-1, we performed RNAi in the wild type and failed to observe any phenotype in the F1 progeny, possibly because jun-1 mRNA was not eliminated (unpublished observations). Thus, we performed similar experiments in two RNAi-sensitive strains. In rrf-3(pk1426); jun-1(RNAi) worms, we observed an egg-laying phenotype and some distal tip cell migration defects, but minimal sterility. However, in jun-1(RNAi); eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) worms, we saw phenotypes similar to those caused by fos-1 RNAi (Table 1). Together, these results show that fos-1 and jun-1 have multiple, overlapping functions in the reproductive system.

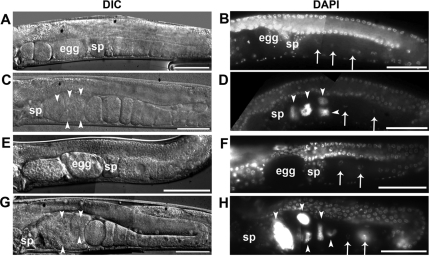

fos-1 and jun-1 Are Required for Ovulation

The high penetrance of the sterile phenotype in fos-1(RNAi) and jun-1(RNAi); eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) worms prompted us to ask how C. elegans AP-1 proteins promote fertility. When we examined gonad morphology and germ cell development in younger animals, we found that fos-1(RNAi) worms seemed normal before ovulation began and did not show an obvious oogenesis defect, which is different from fos-1 deletion alleles fos-1(ar105) and fos-1(km30) (see the following sections for details). However, the oocytes failed to enter the spermatheca in almost all of the young adults examined (93%; n = 79). Consequently, these worms accumulated Emo in the proximal gonad (Figure 2, C and D), a phenomenon that occurs when oocytes mature but are not ovulated or fertilized (Iwasaki et al., 1996). We observed a similar Emo phenotype in jun-1(RNAi); eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) worms (Figure 2, G and H).

Figure 2.

fos-1 and jun-1 are necessary for ovulation. Shown are representative DIC (left) and DAPI (right) images of worms treated with vector only (A and B) and fos-1 RNAi (C and D) in N2, or vector only (E and F) and jun-1 RNAi (G and H) in the RNAi sensitive strain eri-1(mg366); lin15B(n744). Endomitotic oocytes are indicated by arrowheads, and nuclei of oocytes are indicated with arrows. sp, spermatheca. Bar, 50 μm.

FOS-1 Acts in the Soma to Regulate Ovulation

The Emo phenotype is characteristic of an ovulation defect. Ovulation relies on proper signaling and function by sperm and oocytes in the germ line, by sheath cells and spermathecal valve cells in the soma. To determine which of these cells were responsible for the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms, we used rrf-1(pk1417) mutants, which are deficient in somatic RNAi (Sijen et al., 2001). We found that rrf-1(pk1417); fos-1(RNAi) worms showed much less sterility than fos-1(RNAi) in N2 worms (Table 1). This result supports the hypothesis that fos-1 acts in the soma to regulate ovulation. By contrast, sterility resulting from the knockdown of fog-3, a gene necessary for spermatogenesis (Ellis and Kimble, 1995) was not rescued in rrf-1(pk1417) worms. Thus, RNA interference is still functional in the germ line of this strain (Table 1).

FOS-1 Controls the Dilation of the Distal Spermathecal Valve

The somatic tissues involved in ovulation include both sheath cells and the distal spermatheca (McCarter et al., 1997, 1999). To see whether the defects in the fos-1(RNAi) worms were due to inadequate sheath cell contractions or to improper dilation of the distal spermathecal valve, we recorded these processes in living animals. Because endomitotic oocytes trapped in the proximal gonad obscure sheath cell contractions (Yin et al., 2004), we examined only the first ovulation in fos-1(RNAi) worms, using time-lapse microscopy (Supplemental Figure 1A and Supplemental Video 1). This time-lapse imaging also allowed the observation of other critical steps in ovulation, including oocyte maturation (as characterized by nuclear envelope breakdown and cortical rearrangement) and spermathecal valve dilation. In control worms, ovulations progressed normally (n = 5 animals), leading to the movement of oocytes into the spermatheca and the release of fertilized eggs into the uterus. However, all oocytes in fos-1(RNAi) worms failed to enter the spermatheca, even though oocyte maturation occurred normally (n = 4 animals; Supplemental Video 1). Quantification of sheath cell contractions indicated that there was only a slight difference in basal and ovulatory sheath cell contractions in fos-1(RNAi) worms when compared with vector controls (Supplemental Figure 1B). Because even untreated eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) animals have reduced brood sizes and some ovulation defects (unpublished observations), we did not record ovulations in jun-1(RNAi); eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) worms.

To see whether the lack of spermathecal valve dilation in fos-1(RNAi) worms was due to defects in spermathecal development, we performed fos-1 RNAi in a strain that expresses GFP in spermathecal cells (Mohler et al., 1998; Michaux et al., 2001). Knockdown of fos-1 in these animals did not cause detectable changes in the expression or localization of the ajm-1::gfp reporter in the spermatheca (data not shown). These results suggest that the primary defect in fos-1 and jun-1 RNAi-treated worms is a failure in distal spermathecal valve dilation.

fos-1 and jun-1 Deletion Mutants Exhibit Multiple Defects in the Reproductive System

To confirm the RNAi results, we isolated fos-1(km30), which deletes an exon encoding part of the bZIP region, which is shared by FOS-1A and FOS-1B. The fos-1(km30) homozygotes showed severe defects in oocyte development, which prevented us from analyzing ovulation. However, fos-1(km30) heterozygotes displayed several phenotypes associated with reproduction, including sterility (11%), a protruding vulva (8%), a ruptured gonad (3%), the presence of debris or torn oocytes in the spermatheca (28%) and uterus (22%), and unfertilized oocytes in the uterus (11%) (n = 36). Thus, fos-1 regulates many developmental and physiological processes in the reproductive system.

We also studied jun-1(gk557), which deletes the bZIP-coding region (C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium). Reverse transcription-PCR analyses verified the absence of all isoforms (data not shown). Although jun-1(gk557) animals showed multiple defects in the reproductive system and had a reduced brood size, we only observed 5.1% sterility (Supplemental Table 2). Thus, jun-1 and fos-1 have overlapping phenotypes, but they are not identical in their effects on reproduction.

The ovulation defect we observed in jun-1(RNAi); eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) worms might have been due to two distinct causes—the eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) strain might enhance the effectiveness of RNAi against jun-1 or eri-1 and lin-15B might interact genetically with jun-1 to regulate ovulation. Thus, we built jun-1(gk557); lin-15B(n744) double mutants for analysis. Because of decreased fertility, we could not build an eri-1; lin-15b; jun-1 triple mutant. However, we did find that jun-1(gk557); lin-15B(n744) double mutants showed a high percentage of the Emo phenotype compared with either jun-1(gk557) or lin-15B(n744) single mutants (Supplemental Table 3). Thus, jun-1 and lin-15B are partially redundant for the control of ovulation. In addition, we performed RNAi in jun-1(gk557) animals and observed that knockdown of eri-1, lin-15B, or both genes increased sterility (Supplemental Table 4). Together, these results strongly suggest that jun-1 has multiple roles in the reproductive system. Furthermore, the regulation of ovulation by jun-1 is influenced by the activities of eri-1 and lin-15B.

fos-1 Genetically Interacts with Genes in the IP3 Signaling Pathway

Genetic analysis demonstrated that the IP3 signaling pathway is responsible for sheath cell contractions, distal spermathecal valve dilation, and spermatheca-uterine valve dilation through IP3-induced calcium release (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). Thus, we determined whether increased IP3 levels could rescue the sterility induced by fos-1 RNAi. We used three mutants that suppress the ovulation defects of lin-3 mutants—a gain-of-function mutation in itr-1, and loss-of-function mutations in either ipp-5 or lfe-2. We found that ipp-5(sy605) suppressed the sterility induced by fos-1 RNAi, although neither lfe-2(sy326) nor itr-1(sy327) affected the phenotype. To exclude the possibility that the ipp-5 mutation affects RNA interference, we performed RNAi against unc-112, a gene required for the assembly of muscle dense bodies and normal movement (Rogalski et al., 2000). We observed comparable levels of uncoordinated animals when RNAi was performed in wild type or ipp-5(sy605) worms (Table 2). Thus, the RNAi machinery is not compromised in ipp-5 mutants, which implies that the defect in the dilation of the distal spermathecal valve in fos-1(RNAi) worms is due to decreased levels of IP3 in the spermatheca.

Table 2.

Genetic interactions of fos-1 with the IP3 pathway

| Strain | RNAi treatment (n) | Ste (%) | Unc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Vector (99) | 0.0 | N.D. |

| N2 | fos-1 (133) | 90.8 | N.D. |

| ipp-5(sy605) | Vector (98) | 1.4 | N.D. |

| ipp-5(sy605) | fos-1 (68) | 19.9* | N.D. |

| N2 | Vector (634) | N.D. | 0.0 |

| N2 | unc-112 (427) | N.D. | 100.0 |

| ipp-5(sy605) | Vector (582) | N.D. | 0.0 |

| ipp-5(sy605) | unc-112 (638) | N.D. | 98.2 |

| unc-24(e138) | Vector (201) | 0.0 | N.D. |

| unc-24(e138) | fos-1 (178) | 93.1 | N.D. |

| unc-24(e138); itr-1(sy327) | Vector (191) | 0.0 | N.D. |

| unc-24(e138); itr-1(sy327) | fos-1 (141) | 90.8 | N.D. |

| unc-38(x20) | Vector (211) | 0.3 | N.D. |

| unc-38(x20) | fos-1 (128) | 100.0 | N.D. |

| unc-38(x20); lfe-2(sy326) | Vector (224) | 0.3 | N.D. |

| unc-38(x20); lfe-2(sy326) | fos-1 (100) | 97.4 | N.D. |

N.D., not determined; Ste, sterile; Unc, uncoordinated.

Number of worms observed is in parentheses.

*p < 0.05 compared with fos-1 RNAi in N2 worms.

fos-1 and jun-1 Regulate the Expression of plc-1 in the Spermatheca

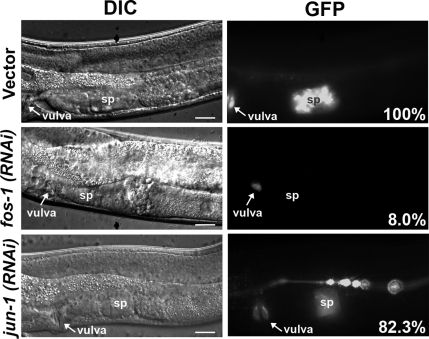

Because AP-1 proteins are transcription factors, we suspected that fos-1 and jun-1 might regulate the expression of molecules in the IP3 signaling pathway. Thus, we performed fos-1 and jun-1 RNAi in plc-1, plc-3, ipp-5 and itr-1 GFP reporter strains (Clandinin et al., 1998; Gower et al., 2001; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). RNA interference against fos-1 reduced the expression of plc-1::gfp in the spermatheca to 8.0% of the vector control, and RNA interference against jun-1 reduced the expression of plc-1::gfp to 82.3% (Figure 3). This slight reduction of plc-1::gfp expression in the jun-1(RNAi) worms mirrors the low level of sterility found in these animals. However, plc-1::gfp expression in other tissues including the vulva, head, and tail seemed unaltered in all of these experiments. Furthermore, we saw no obvious changes in the expression of plc-3::gfp, ipp-5::gfp or itr-1::gfp in the spermatheca of fos-1(RNAi) or jun-1(RNAi) worms (unpublished observations). These results suggest that fos-1 and jun-1 regulate plc-1 expression in the spermatheca.

Figure 3.

fos-1 and jun-1 regulate plc-1 expression. (A) Effect of fos-1 and jun-1 RNAi on plc-1::gfp expression. Shown are DIC (left) and GFP (right) images of worms treated with vector only, fos-1 RNAi, or jun-1 RNAi. The numbers in the bottom right corners of the GFP images are quantified percentage of fluorescence intensity relative to vector-treated worms. Arrows indicate position of the vulva. Bar, 10 μm.

To see whether down-regulation of plc-1 transcription in the spermatheca was responsible for the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms, we studied transgenic lines that can be induced to express PLC-1 by heat shock. In fos-1(RNAi) animals, overexpression of PLC-1 reduced the Emo phenotype by 58% (Table 3). However, overexpression of PLC-1 did not alter the protruding vulva phenotype. Thus, reduced expression of PLC-1 in the spermatheca is responsible for the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms.

Table 3.

Rescue of the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms by plc-1

| Strain | RNAi treatment (n) | Heat shock | Emo (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hs::plc-1 | Vector (61) | No | 0.0 |

| hs::plc-1 | fos-1 (62) | No | 83.4 |

| hs::plc-1 | fos-1 (68) | Yes | 35.5 |

hs, hsp-16.41.

Number of worms observed is in parentheses.

fos-1b, jun-1a-c and jun-1d Are Coexpressed in the Spermatheca

Two isoforms of fos-1 have been identified previously (Sherwood et al., 2005), and four isoforms of jun-1 were predicted (www.wormbase.org). To confirm these isoforms, we performed 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. These studies confirmed the expression of fos-1a and fos-1b and identified six isoforms of jun-1, which all share a common bZIP region (Supplemental Figure 2).

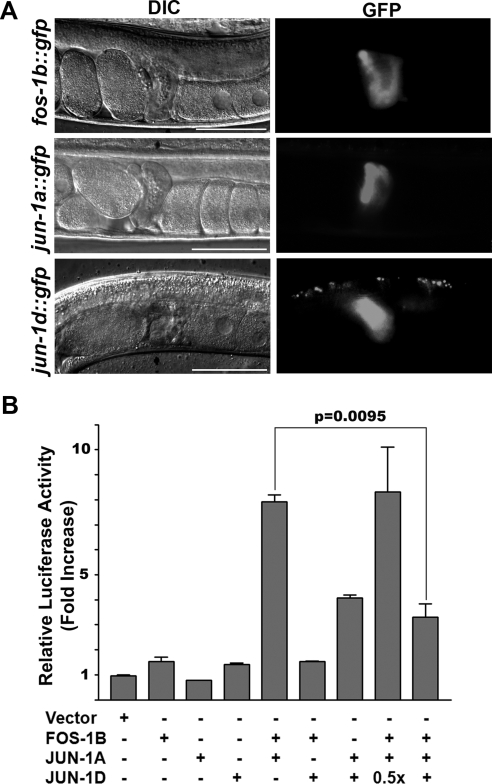

fos-1a is expressed in the anchor cell and uterus throughout gonadogenesis and regulates both anchor cell invasion and uterine development (Rogalski et al., 2000; Oommen and Newman, 2007). Although fos-1b is expressed in several tissues, its function had been unknown (Sherwood et al., 2005). To see whether fos-1b was expressed in the spermatheca, we used 3.4 kb of genomic DNA upstream of its transcriptional start site to build a GFP reporter plasmid. Transgenic worms carrying this plasmid expressed GFP in the spermatheca (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

fos-1b, jun-1abc, and jun-1d are expressed in the spermatheca. (A) Expression of fos-1b, jun-1abc, and jun-1d in the spermatheca. Shown are DIC (left) and GFP (right) images in transgenic worms carrying the GFP reporters for fos-1b, jun-1abc (jun-1a), or jun-1d. Scale, 50 μm. (B) Effect of FOS-1B, JUN-1A, and JUN-1D on activation of an AP-1 luciferase reporter that contains three TPA response elements (TGAGTCA). +, 0.5 μg; 0.5×, 0.25 μg.

Because jun-1a is the longest isoform, and differs only in exons 1 or 2 from jun-1b and jun-1c, we constructed a single transcriptional reporter for jun-1a-c. In addition, we created transcriptional reporters for jun-1d, jun-1e, and jun-1f. Examination of GFP expression in transgenic worms revealed that jun-1a-c and jun-1d are expressed in the spermatheca (Figure 4A), whereas jun-1e and jun-1f are not (unpublished observations). Hence, fos-1b and jun-1a, b, c, or d were likely to be responsible for the RNAi phenotypes we had observed.

The expression of multiple jun-1 isoforms in the spermatheca suggested that these isoforms might interact to coordinate the transcription of target genes. For example, in mammals, the transcription of AP-1 target genes is subject to negative regulation by some AP-1 proteins that share essentially the same bZIP domain, such as JunB and JunD (Zenz and Wagner, 2006). In C. elegans, JUN-1D is one of three short isoforms that contain the bZIP domain and little else. Because the bZIP domains of JUN-1 and FOS-1 bind the consensus TPA response element (TRE) binding site as heterodimers as well as homodimers (unpublished observations), we examined the transcriptional potential of FOS-1B, JUN-1A, and JUN-1D. To do this, we used luciferase reporter gene assays in COS-1 cells. Although FOS-1B, JUN-1A, or JUN-1D alone showed minimal activation of the reporter gene, coexpression of JUN-1A with FOS-1B significantly activated the AP-1 reporter. However, coexpression of JUN-1D with FOS-1B had no effect (Figure 4B). Instead, coexpression of JUN-1D inhibited activation of the reporter by FOS- 1B/JUN-1A when an equal amount of the plasmid encoding JUN-1D was cotransfected. These results suggest that JUN-1A and JUN-1D exhibit opposite effects on the activation of target genes when they form heterodimers with FOS-1B.

DISCUSSION

FOS-1 and JUN-1 Regulate plc-1 Expression in the Spermatheca to Control Distal Spermathecal Valve Dilation

AP-1 family proteins regulate many physiological responses in cells and in animals, and the deregulation of these proteins is involved in numerous pathologies (Karin et al., 1997; Wagner, 2001). However, the role of AP-1 proteins in the reproductive system remains largely unexplored, due to the lack of appropriate model systems. Our findings that FOS-1 and JUN-1 control spermathecal valve dilation, along with the known role of FOS-1 in anchor cell invasion and cell fate specification in the uterus (Sherwood et al., 2005; Hwang et al., 2007; Oommen and Newman, 2007; Rimann and Hajnal, 2007; Sapir et al., 2007), establish C. elegans as a model for the control of reproduction by AP-1 proteins.

Spermathecal valve dilation is essential for successful ovulation. Genetic analysis showed that it depends on several genes that act in the IP3 signaling pathway to control calcium levels (Clandinin et al., 1998; Bui and Sternberg, 2002; Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). We present several lines of evidence that FOS-1 and JUN-1 regulate plc-1 transcription specifically in the spermatheca. First, fos-1b, jun-1a-c and jun-1d are all coexpressed in the spermatheca, along with plc-1. Second, knockdown of fos-1 or jun-1 decreased expression of a plc-1::gfp reporter in the spermatheca, without affecting its expression in other tissues. Third, the lack of distal spermathecal valve dilation caused by fos-1 RNAi was suppressed by ipp-5(sy605), a mutant allele that increases IP3 levels by inhibiting the metabolism of IP3, but was not suppressed by lfe-2(sy326) or itr-1(sy327). This pattern of suppression is identical to that observed for plc-1 with these mutations (Kariya et al., 2004). Fourth, overexpression of PLC-1 rescued the Emo phenotype in fos-1(RNAi) worms. Thus, our studies provide a link between fos-1/jun-1 and plc-1 in C. elegans.

Other PLC isozymes in worms have been implicated in the regulation of all three major rhythmic programs—pharyngeal pumping, ovulation and defecation (Kariya et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004; Espelt et al., 2005; Norman et al., 2005). Thus, it will be interesting to determine whether AP-1 proteins also regulate the transcription of any of these PLC isozymes. In mammals, AP-1 proteins regulate circadian rhythms by controlling the transcription of critical target genes (Kornhauser et al., 1992; Crosio et al., 2000; Hirayama et al., 2005), so the role of AP-1 proteins in rhythmic behaviors might be ancient.

Although we show that fos-1 and jun-1 regulate ovulation via plc-1, there might be additional target genes involved in ovulation. For example, that overexpressing PLC-1 in fos-1(RNAi) worms only partially rescues the ovulation defect and fos-1 RNAi causes a slight reduction in sheath cell contractions could indicate that fos-1 and jun-1 control additional targets. This possibility is supported by the penetrance of the ovulation defect in fos-1(RNAi) worms, which is higher than that in plc-1 deletion mutants (Kariya et al., 2004).

Chromatin Remodeling Influences Transcriptional Regulation of AP-1 Target Genes

In C. elegans, three classes of genes can interact to create a synthetic multivulval (SynMuv) phenotype (Fay and Yochem, 2007). Genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that these genes influence chromatin remodeling (Thomas et al., 2003; Ceol and Horvitz, 2004; Poulin et al., 2005; Cui et al., 2006; Harrison et al., 2006). It is interesting that jun-1(RNAi) animals only showed an ovulation defect in the strain eri-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744). Although eri-1 is an RNAse that influences RNA interference, lin-15B is a gene with SynMuvB activity (Wang et al., 2005). Furthermore, we found that a lin-15B mutation, n744, was sufficient for this interaction with jun-1. Finally, a general RNAi screen identified 57 genes, including jun-1, that interact with SynMuv genes like lin-15B, lin-35 and lin-37 (Ceron et al., 2007). Thus, a complex regulatory mechanism involving chromatin remodeling might influence the transcriptional regulation of plc-1 by jun-1.

Knocking down fos-1 in the wild type is sufficient to down-regulate plc-1 transcription and to cause an ovulation defect, but the same is not true for jun-1. However, several observations support an alternative model. First, several JUN-1 isoforms are expressed in the spermatheca. Second, FOS-1B/JUN-1A positively regulates a reporter gene in tissue culture, but JUN-1D antagonizes this interaction. Thus, FOS-1/JUN-1A might promote transcription of plc-1 in the spermatheca, and JUN-1D might block transcription. If correct, this model would explain the weak phenotype of jun-1 deletion mutants, since both its positive and negative activities would be eliminated. In addition, this model implies that the enhancement of the ovulation defect seen in jun-1(mg366); lin-15B(n744) mutants could have been caused by a differential effect of chromatin alterations on the activity of the two JUN-1 isoforms. This inference is supported by the observation that knockdown of jun-1 in the background of lin-35 or lin-37 mutations also causes sterility (Ceron et al., 2007). Further analysis of the interactions between jun-1 and other SynMuv genes could provide insight into the transcriptional regulation of AP-1 target genes via chromatin remodeling.

AP-1 Dimerization in Transcriptional Regulation of Target Genes

AP-1 has been extensively studied over the past two decades. One challenge in the field is to assign specific cellular or developmental roles to individual AP-1 dimers. This has been impeded by the presence of multiple AP-1 proteins in mammals, allowing potential dimerization of any single AP-1 protein with several partners. These complexities contribute to functional complementation when only a single AP-1 gene is knocked out (Jochum et al., 2001). By contrast, model organisms with reduced genetic redundancy allow functional analysis of AP-1 dimers and their corresponding target genes, as shown by studies in Drosophila (Kockel et al., 2001; Ciapponi and Bohmann, 2002).

At least two different isoforms, jun-1a and jun-1d, are coexpressed with fos-1b in the spermatheca. Our proposal that multiple AP-1 dimers with distinct transcriptional potential could be formed in the spermatheca is based on this fact, and on the ability of the bZIP domains of FOS-1 and JUN-1 to form homodimers and heterodimers (unpublished observations). Furthermore, it is supported by the observation that JUN-1A and JUN-1D play opposite roles in activating an AP-1 reporter gene. We have identified four potential TRE sites in the promoter used for the plc-1::gfp reporter strain (unpublished observations). Thus, future characterization of the plc-1 promoter and its regulation by different AP-1 proteins should show how these AP-1 proteins coordinate the transcription of plc-1 in the spermatheca and could provide a model system for studying the interaction of different AP-1dimers on transcription.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Hu laboratory for valuable discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, Apinya Suppatkul and Jonathan Smith for laboratory assistance, and Xuehong Deng for valuable support for the laboratory and for performing the luciferase reporter gene assays. We thank David Allen for video editing. We are indebted to the Strome laboratory for valuable discussions and to Susan Strome for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. We also thank the C.G.C., Paul Sternberg, Howard Baylis, and Kevin Strange for strains. S.M.H. was supported by the Purdue University Ross Fellowship and the Bilsland Dissertation Fellowship, R.E.E. was supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society, and C.D.H. was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0833) on July 1, 2009.

REFERENCES

- Bui Y. K., Sternberg P. W. Caenorhabditis elegans inositol 5-phosphatase homolog negatively regulates inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate signaling in ovulation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1641–1651. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceol C. J., Horvitz H. R. A new class of C. elegans synMuv genes implicates a Tip60/NuA4-like HAT complex as a negative regulator of Ras signaling. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:563–576. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceron J., Rual J. F., Chandra A., Dupuy D., Vidal M., van den Heuvel S. Large-scale RNAi screens identify novel genes that interact with the C. elegans retinoblastoma pathway as well as splicing-related components with synMuv B activity. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi L., Bohmann D. An essential function of AP-1 heterodimers in Drosophila development. Mech. Dev. 2002;115:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin T. R., DeModena J. A., Sternberg P. W. Inositol trisphosphate mediates a RAS-independent response to LET-23 receptor tyrosine kinase activation in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;92:523–533. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80945-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosio C., Cermakian N., Allis C. D., Sassone-Corsi P. Light induces chromatin modification in cells of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/81767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Kim E. B., Han M. Diverse chromatin remodeling genes antagonize the Rb-involved SynMuv pathways in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. E., Kimble J. The fog-3 gene and regulation of cell fate in the germ line of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:561–577. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelt M. V., Estevez A. Y., Yin X., Strange K. Oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in the isolated Caenorhabditis elegans intestine: role of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and phospholipases C beta and gamma. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:379–392. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay D. S., Yochem J. The SynMuv genes of Caenorhabditis elegans in vulval development and beyond. Dev. Biol. 2007;306:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Barton M. K., Kimble J., Schedl T. gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:579–606. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S. Characterization of mutations induced by ethyl methanesulfonate, UV, and trimethylpsoralen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;269:64–69. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower N. J., Temple G. R., Schein J. E., Marra M., Walker D. S., Baylis H. A. Dissection of the promoter region of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor gene, itr-1, in C. elegans: a molecular basis for cell-specific expression of IP3R isoforms. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:145–157. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. M., Ceol C. J., Lu X., Horvitz H. R. Some C. elegans class B synthetic multivulva proteins encode a conserved LIN-35 Rb-containing complex distinct from a NuRD-like complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16782–16787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608461103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt S. M., Shyu Y. J., Duren H. M., Hu C. D. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis of protein interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2008;45:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama J., Cardone L., Doi M., Sassone-Corsi P. Common pathways in circadian and cell cycle clocks: light-dependent activation of Fos/AP-1 in zebrafish controls CRY-1a and WEE-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10194–10199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502610102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang B. J., Meruelo A. D., Sternberg P. W. C. elegans EVI1 proto-oncogene, EGL-43, is necessary for Notch-mediated cell fate specification and regulates cell invasion. Development. 2007;134:669–679. doi: 10.1242/dev.02769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K., McCarter J., Francis R., Schedl T. emo-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans Sec61p gamma homologue, is required for oocyte development and ovulation. J. Cell Biol. 1996;134:699–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum W., Passegue E., Wagner E. F. AP-1 in mouse development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:2401–2412. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Martinez-Campos M., Zipperlen P., Fraser A. G., Ahringer J. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0002. doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Liu Z., Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya K., Bui Y. K., Gao X., Sternberg P. W., Kataoka T. Phospholipase C epsilon regulates ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 2004;274:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockel L., Homsy J. G., Bohmann D. Drosophila AP-1, lessons from an invertebrate. Oncogene. 2001;20:2347–2364. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser J. M., Nelson D. E., Mayo K. E., Takahashi J. S. Regulation of jun-B messenger RNA and AP-1 activity by light and a circadian clock. Science. 1992;255:1581–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.1549784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Deng X., Shyu Y. J., Li J. J., Taparowsky E. J., Hu C. D. Mutual regulation of c-Jun and ATF2 by transcriptional activation and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2006;25:1058–1069. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter J., Bartlett B., Dang T., Schedl T. Soma-germ cell interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans: multiple events of hermaphrodite germline development require the somatic sheath and spermathecal lineages. Dev. Biol. 1997;181:121–143. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter J., Bartlett B., Dang T., Schedl T. On the control of oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 1999;205:111–128. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaux G., Legouis R., Labouesse M. Epithelial biology: lessons from Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;277:83–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A., Nguyen V. Q., Lee M. H., Kosinski M., Schedl T., Caprioli R. M., Greenstein D. A sperm cytoskeletal protein that signals oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation. Science. 2001;291:2144–2147. doi: 10.1126/science.1057586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A., Ruest P. J., Kosinski M., Hanks S. K., Greenstein D. An Eph receptor sperm-sensing control mechanism for oocyte meiotic maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2003;17:187–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.1028303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler W. A., Simske J. S., Williams-Masson E. M., Hardin J. D., White J. G. Dynamics and ultrastructure of developmental cell fusions in the Caenorhabditis elegans hypodermis. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1087–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman K. R., Fazzio R. T., Mellem J. E., Espelt M. V., Strange K., Beckerle M. C., Maricq A. V. The Rho/Rac-family guanine nucleotide exchange factor VAV-1 regulates rhythmic behaviors in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;123:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oommen K. S., Newman A. P. Co-regulation by Notch and Fos is required for cell fate specification of intermediate precursors during C. elegans uterine development. Development. 2007;134:3999–4009. doi: 10.1242/dev.002741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin G., Dong Y., Fraser A. G., Hopper N. A., Ahringer J. Chromatin regulation and sumoylation in the inhibition of Ras-induced vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2005;24:2613–2623. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimann I., Hajnal A. Regulation of anchor cell invasion and uterine cell fates by the egl-43 Evi-1 proto-oncogene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 2007;308:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski T. M., Mullen G. P., Gilbert M. M., Williams B. D., Moerman D. G. The UNC-112 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a novel component of cell-matrix adhesion structures required for integrin localization in the muscle cell membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:253–264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual J. F., et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir A., Choi J., Leikina E., Avinoam O., Valansi C., Chernomordik L. V., Newman A. P., Podbilewicz B. AFF-1, a FOS-1-regulated fusogen, mediates fusion of the anchor cell in C. elegans. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:683–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood D. R., Butler J. A., Kramer J. M., Sternberg P. W. FOS-1 promotes basement-membrane removal during anchor-cell invasion in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;121:951–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibatohge M., Kariya K., Liao Y., Hu C. D., Watari Y., Goshima M., Shima F., Kataoka T. Identification of PLC210, a Caenorhabditis elegans phospholipase C, as a putative effector of Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6218–6222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu Y. J., Hiatt S. M., Duren H. M., Ellis R. E., Kerppola T. K., Hu C. D. Visualization of protein interactions in living Caenorhabditis elegans using bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:588–596. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijen T., Fleenor J., Simmer F., Thijssen K. L., Parrish S., Timmons L., Plasterk R. H., Fire A. On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell. 2001;107:465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer F., Moorman C., Van Der Linden A. M., Kuijk E., Van Den Berghe P. V., Kamath R., Fraser A. G., Ahringer J., Plasterk R. H. Genome-Wide RNAi of C. elegans Using the Hypersensitive rrf-3 Strain Reveals Novel Gene Functions. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. H., Ceol C. J., Schwartz H. T., Horvitz H. R. New genes that interact with lin-35 Rb to negatively regulate the let-60 ras pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2003;164:135–151. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Court D. L., Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. F. AP-1–Introductory remarks. Oncogene. 2001;20:2334–2335. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Kennedy S., Conte D., Jr, Kim J. K., Gabel H. W., Kamath R. S., Mello C. C., Ruvkun G. Somatic misexpression of germline P granules and enhanced RNA interference in retinoblastoma pathway mutants. Nature. 2005;436:593–597. doi: 10.1038/nature04010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X., Gower N. J., Baylis H. A., Strange K. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling regulates rhythmic contractile activity of myoepithelial sheath cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:3938–3949. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenz R., Wagner E. F. Jun signalling in the epidermis: from developmental defects to psoriasis and skin tumors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;38:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.