Abstract

Crossing the Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) double-knockout mouse with the Cyp1b1(−/−) single-knockout mouse, we generated the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout mouse. In this triple-knockout mouse, statistically significant phenotypes (with incomplete penetrance) included slower weight gain and greater risk of embryolethality before gestational day 11, hydrocephalus, hermaphroditism, and cystic ovaries. Oral benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) daily for 18 days in the Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) produced the same degree of marked immunosuppression as seen in the Cyp1a1(−/−) mouse; we believe this reflects the absence of intestinal CYP1A1. Oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice showed the same “rescued” response as that seen in the Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) mouse; we believe this reflects the absence of CYP1B1 in immune tissues. Urinary metabolite profiles were dramatically different between untreated triple-knockout and wild-type; principal components analysis showed that the shifts in urinary metabolite patterns in oral BaP-treated triple-knockout and wild-type mice were also strikingly different. Liver microarray cDNA differential expression (comparing triple-knockout with wild-type) revealed at least 89 genes up- and 62 genes down-regulated (P-value ≤0.00086). Gene Ontology “classes of genes” most perturbed in the untreated triple-knockout (compared with wild-type) include lipid, steroid, and cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism; nucleosome and chromatin assembly; carboxylic and organic acid metabolism; metal-ion binding; and ion homeostasis. In the triple-knockout compared with the wild-type mice, response to zymosan-induced peritonitis was strikingly exaggerated, which may well reflect down-regulation of Socs2 expression. If a single common molecular pathway is responsible for all of these phenotypes, we suggest that functional effects of the loss of all three Cyp1 genes could be explained by perturbations in CYP1-mediated eicosanoid production, catabolism and activities.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) proteins are heme-thiolate enzymes involved in innumerable cellular functions: eicosanoid synthesis and degradation; cholesterol, sterol, lipid, and bile acid biosynthesis; steroid synthesis and metabolism; biogenic amine synthesis and degradation; vitamin D3 synthesis and metabolism; and hydroxylation of retinoic acid and probably other morphogens. A few P450 enzymes still have no unequivocally identified functions (Nebert and Russell, 2002; Nelson et al., 2004). The mouse and human P450 gene superfamilies contain 102 and 57 protein-coding genes, respectively (Nelson et al., 2004). Drugs, environmental procarcinogens and toxicants—as well as the more than 150 eicosanoids—are metabolized largely by enzymes in the CYP1, CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4 families (Nebert and Dalton, 2006).

Among the 18 mammalian P450 families, CYP1 comprises three orthologous members in human and mouse: CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1. The three CYP1 genes are up-regulated via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), a transcription factor that binds as a heterodimer with the AHR nuclear transporter to DNA motifs known as AHR response elements (Nebert and Russell, 2002; Nebert et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 2004). CYP1 inducers usually are ligands that activate the AHR, thereby stimulating the receptor to migrate from cytosol to the nucleus (Tukey et al., 1982); these ligands include benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (Nebert et al., 2004; Nebert and Dalton, 2006). Several classes of endogenous compounds that activate the AHR have been reported: 1) tryptophan metabolites and other indole-containing molecules; 2) tetrapyrroles such as bilirubin and biliverdin; 3) sterols such as 7-ketocholesterol and equilenin; 4) fatty acid metabolites, including several prostaglandins and lipoxin A4; and 5) the ubiquitous second-messenger cAMP (McMillan and Bradfield, 2007). However, the dissociation constant of binding (Kd) for most of these compounds is not as low as one would expect for physiologically relevant ligands of the AHR. [Mouse (and rat) genes are italicized with only the first letter capitalized (e.g., Cyp1a1, Ahr), whereas human and other nonrodent or generic genes are italicized with all letters capitalized (e.g., CYP1A1, AHR). Rodent, human and generic cDNA/mRNA/protein/enzyme activities are never italicized and all letters always capitalized (e.g., CYP1A1, AHR).]

The Cyp1a1(−/−) (Dalton et al., 2000), Cyp1a2(−/−) (Liang et al., 1996), and Cyp1b1(−/−) (Buters et al., 1999) knockout mouse lines have been generated; from these, straightforward genetic crosses were performed to create the Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1a2/1b1(−/−) double-knockout mice (Uno et al., 2006). The Cyp1a1 and Cyp1a2 genes are located on mouse chromosome 9 at cM 31.0, while the mouse Cyp1b1 gene is located on mouse chromosome 17. The Cyp1a2 gene arose from a Cyp1a1 duplication event ~450 million years ago. The two mouse genes are oriented head-to-head, sharing a 13,954-base pair bidirectional promoter; therefore, creation of the Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) double-knockout line was successful by means of an interchromosomal Cre/loxP-mediated excision of 26,173 base pairs (Dragin et al., 2007). A straightforward genetic cross between this double-knockout and the Cyp1b1(−/−) line has now generated the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout animal. Herein we describe the phenotype observed in this mouse line—in which for the first time all three Cyp1 gene activities have been ablated.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

BaP and zymosan A were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). TCDD was bought from Accustandard, Inc. (New Haven, CT). All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from either Aldrich Chemical Company (Milwaukee, WI) or Sigma at the highest available grades.

Animals

The generation of the Cyp1a1(−/−) (Dalton et al., 2000), Cyp1a2(−/−) (Liang et al., 1996), and Cyp1b1(−/−) (Buters et al., 1999) mouse lines and studies with the Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1a2/1b1(−/−) double-knockout lines (Uno et al., 2006) have been described. The Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) double-knockout was generated via Cre-mediated interchromosomal excision (Dragin et al., 2007). All these genotypes have been backcrossed into the C57BL/6J background for eight generations, ensuring that the knockout genotypes reside in a genetic background that is >99.8% C57BL/6J (Nebert et al., 2000a). Age-matched C57BL/6J Cyp1(+/+) wild-type mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) therefore make comparable controls. Breeding of the Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) with the Cyp1b1(−/−) mouse produced the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout line in the >99.8% C57BL/6J background. Except for the breeding studies, all other experiments were carried out in male mice and begun at 6 ± 1 weeks of age. In some instances, pretreatment with intraperitoneal TCDD (15 μg/kg; as the prototypical Cyp1 inducer) in corn oil was given as a single dose 48 h before sacrifice. TCDD is known to up- and down-regulate dozens of genes that have AHR response elements in their regulatory regions. All animal experiments were approved by, and conducted in accordance with, the National Institutes of Health standards for the care and use of experimental animals and the University Cincinnati Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Breeding, In Utero Deaths, and Teratology

Various combinations of female and male genotypes were crossed, and the intrauterine contents were examined at gestational day (GD) 11, GD13, GD15, GD17, GD19, and within hours of birth. GD0 was the day on which a vaginal plug was first detected. Genotyping for the ablated Cyp1a1_1a2 locus (Dragin et al., 2007) and absence of the Cyp1b1 gene (Buters et al., 1999) was carried out in embryos and fetuses (living or dead), resorbed fetal material, newborns, and weanlings.

Dietary BaP Experiments

BaP (125 mg/kg) was given orally (Uno et al., 2004, 2006, 2008). Lab rodent chow (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) was soaked in BaP-laced corn oil (10 mg/ml) for at least 24 h before presentation to mice; BaP at this concentration was calculated to be equivalent to ~125 mg/kg/day (Robinson et al., 1975). After 5 days in some mice, a 30-μl blood sample was drawn from the saphenous vein, and total blood BaP was measured; in addition, after 5 days of oral BaP, LC-MS studies of urinary metabolite profiles were determined. For all other studies, mice were sacrificed after 18 days of oral BaP; tissues (liver, spleen, and thymus) were removed, weighed, and frozen as quickly as possible in liquid nitrogen (or prepared for pathology analysis). Peripheral blood and bone marrow smears were made for white cell differential counts. Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities in mouse plasma were also determined (Uno et al., 2004, 2006). Tissues were removed between 9:00 AM and 10:00 AM to exclude any circadian rhythm effects. For each group, n = 4 to 6 mice.

Detection of BaP in Blood

BaP levels in whole blood were quantified by modification of previously described methods (García Falcón et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2000). Whole blood (30 μl) was extracted three times with ethyl acetate/acetone mixture [2:1 (v/v)]. The organic extracts were pooled and dried under argon, and the residue was resuspended in 250 μl of acetonitrile. An aliquot (100 μl) was injected onto a Nova-Pak C18 reversed-phase column (4-μm, 150 × 3.9 mm i.d.; Waters Associates, Milford, MA). High-performance liquid chromatography analysis was conducted on a Waters model 600 solvent controller, equipped with a fluorescence detector (F-2000; Hitachi). Isocratic separation was performed using an acetonitrile/water [85:15 (v/v)] mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 294 and 404 nm, respectively. BaP concentrations in blood were calculated by comparing the peaks of samples with those of control blood that had been spiked with different known concentrations of BaP. The calibration curve for BaP showed excellent linearity (correlation coefficient/r > 0.998); four major and several minor BaP metabolites were found to run far ahead of BaP on the column and thus did not interfere. The detection limit (defined as three times the signal-to-noise ratio) was 0.05 pg/μl, and the limit of BaP quantification was determined to be 0.20 pg/μl. The intra- and interday precision of repeated analyses (n = 4) gave us coefficients of variation of ≤12%.

Biohazard Precaution

BaP and TCDD are highly toxic chemicals and regarded as likely human carcinogens. All personnel were instructed in safe handling procedures. Lab coats, gloves, and masks were worn at all times, and contaminated materials were collected separately for disposal by the Hazardous Waste Unit or by independent contractors. BaP- and TCDD-treated mice were housed separately, and their carcasses were considered contaminated biological materials.

Urine Collection

Untreated or oral BaP (125 mg/kg/day for 5 days)-treated Cyp1(+/+) and Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice were placed individually in metabolic cages overnight, with food and water provided ad libitum. Urine was collected for 24 h and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. For each of the four groups, urine samples were collected from n = 6 individual mice.

LC-MS-Based Analysis of Urinary Metabolite Profiles

Urine samples from untreated versus oral BaP-treated Cyp1(+/+) and Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice were prepared for UPLC-QTOFMS analysis by mixing 50 μl of urine with 200 μl of 50% aqueous acetonitrile and centrifuging at 18,000g for 5 min to remove protein and particulates. A 200-μl aliquot of the supernatant fraction was transferred to an auto-sampler vial and a 5-μl aliquot of each sample was injected into the UPLC-QTOFMS system (Waters). An Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (Waters) was used to separate urinary metabolites at 30°C. The mobile-phase flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, with a gradient ranging from water to 95% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid during a 10-min run. The QTOF Premier mass spectrometer was operated in the positive electrospray ionization mode. Capillary voltage and cone voltage were maintained at 3 kV and 20 V, respectively. Source temperature and desolvation temperature were set at 120°C and 350°C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as both the cone gas (50 L/h) and the desolvation gas (600 L/h), and argon was the collision gas. For accurate mass measurement, the QTOFMS was calibrated with sodium formate solution (m/z range, 100-1000) and monitored in real time by intermittent injections of the lock mass sulfadimethoxine ([M+H]+ = 311.0814 m/z).

Mass chromatograms and mass spectral data were acquired by MassLynx software in centroided format, and then deconvoluted by MarkerLynx software (Waters) to generate a multivariate-data matrix. The intensity of each ion was calculated as the percentage of total ion counts in the whole chromatogram. Furthermore, the data matrix was exported into SIMCA-P+ software (Umetrics, Kinnelon, NJ), and transformed by mean-centering and Pareto scaling, a technique that increases the importance of low-abundance ions without significant amplification of noise. Principal components were generated by multivariate-data analysis to represent the major latent variables in the data matrix and were described in a scores-scatter plot.

Microarray Hybridization

Six wild-type and six triple-knockout untreated mice (6-week-old male mice) provided the liver RNA; RNA from two mice comprised each group, meaning there were three groups of wild-type and three of triple-knockout. The microarray experiments were carried out essentially as described elsewhere and referenced therein (Sartor et al., 2004). The mouse 70-mer Mouse Exonic Evidence-Based Oligonucleotide (MEEBO) library version 1.05 (25,130 unique gene symbols on the array; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was suspended in 3× SSC at 30 μM and printed at 22°C, with 65% relative humidity, on aminosilane-coated slides (Cel Associates, Inc., Pearland, TX), using a high-speed robotic Omnigrid machine (GeneMachines, San Carlos, CA) with Stealth SMP3 pins (Telechem, Sunnyvale, CA). The complete gene list can be viewed at http://www.beta.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/Products-and-Services/Applications/Nucleic-Acid-Amplification-and-Expression-Profiling/Oligonucleotide-Design/HEEBO-and-MEEBO-Genome-Sets.html. Spot volumes were 0.5 nl, and spot diameters were 75 to 85 μm. The oligonucleotides were cross-linked to the slide substrate by exposure to 600 mJ of ultraviolet light.

Fluorescence-labeled cDNAs were synthesized from total RNA, using an indirect aminoallyl labeling method via an oligo(dT)-primed reverse-transcriptase reaction. The cDNA was decorated with mono-functional reactive cyanine-3 and cyanine-5 dyes (Cy3 and Cy5; GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). The details and a complete description of the slide preparation can be found at http://microarray.uc.edu/Equipments.aspx.

Imaging and data generation were carried out using a GenePix 4000A and GenePix 4000B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and associated software. The microarray slides were scanned with dual lasers having the wavelength frequencies to excite Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence emittance. Images were captured in JPG and TIF files, and DNA spots were captured by the adaptive circle segmentation method. Information extraction for a given spot is based on the median value for the signal pixels and the median value for the background pixels to produce a gene-set data file for all the DNA spots. The Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence signal intensities were normalized.

Microarray Data Normalization and Analysis

We sought to identify differentially expressed genes between untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1(+/+) wild-type mice. Three biological-replicate arrays with one dye flip were carried out. Analysis was performed using R statistical software and the limma Bioconductor package (Smyth, 2004). Data normalization was conducted in two steps for each microarray separately (Sartor et al., 2004). First, background-adjusted intensities were log-transformed and the differences (M) and averages (A) of log-transformed values were calculated as M = log2(X1) – log2(X2) and A = [log2(X1) + log2(X2)]/2, where X1 and X2 denote the Cy5 and Cy3 intensities, respectively. Second, normalization was performed by fitting the array-specific local regression model of M as a function of A. Normalized log-intensities for the two channels were then calculated by adding half the normalized ratio to A for the Cy5 channel and subtracting half the normalized ratio from A for the Cy3 channel. Statistical analysis was performed by first fitting the following analysis-of-variance model for each gene separately: Yijk = μ + Ai + Sj + Ck + εijk, where Yijk corresponds to the normalized log-intensity on the ith array, with the jth treatment, and labeled with the kth dye (k = 1 for Cy5 and 2 for Cy3); μ denotes the overall mean log-intensity, Ai is the effect of the ith array, Sj is the effect of the jth treatment, Ck is the gene-specific effect of the kth dye, and εijk is the error term for the ith array with the jth treatment, and labeled with the kth dye. Estimated -fold changes were calculated from the ANOVA models, and resulting t test statistics from each comparison were modified using an intensity-based empirical Bayesian method (Sartor et al., 2004). This method, an extension of Smyth (2004), obtains more precise estimates of variance by pooling information across genes and accounting for the dependence of variance on probe-intensity levels. Identification of significant genes was accomplished from two avenues. First, the false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated (Reiner et al., 2003); genes with an FDR value of ≤0.10 are considered significantly differentially expressed. Next, discovery of gene categories enriched with differentially expressed genes was performed using DAVID software (Dennis et al., 2003) with a P value of <0.01 significance cutoff for genes. The biological process and molecular-function branches of the Gene Ontology (GO) database (Harris et al., 2004) were tested for enrichment, and genes belonging to those GO terms having a calculated FDR ≤0.10 were considered for further analysis. The mRNA expression of 22 genes of interest was corroborated by Q-PCR studies.

Total RNA Preparation

Untreated wild-type versus triple-knockout mice or TCDD-pretreated wild-type versus triple-knockout mice were always compared. Total RNA from frozen liver was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The quantity of RNA was determined spectrophotometrically by the A260/A280 ratio (SmartSpec 3000; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The quality of RNA was confirmed by separation on a denaturing formaldehyde/agarose/ethidium bromide gel, and then quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Quantum Analytics, Foster City, CA).

Reverse Transcription

Total RNA (2 μg) was added to a reaction containing 3.8 μM oligo(dT)20 and 0.77 mM dNTP—to a final volume of 13 μl. Reactions were incubated at 65°C for 5 min, then 4°C for 2 min. To the reaction mixture, we added 7 μl of solution containing 14 mM dithiothreitol, 40 units of RNaseOUT Recombinant RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen), and 200 units SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Reactions were incubated at 50°C for 50 min, followed by 75°C for 10 min (to inactivate the reverse transcriptase). Distilled water (80 μl) was added to the isolated cDNA; these samples were then stored at −80°C until use.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Using the Superscript II RNase H-reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen), hepatic total RNA was reverse-transcribed. After this, Q-PCR was conducted using Brilliant SYBR Green Q-PCR (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Data were normalized to reverse transcription-PCR detection of β-actin mRNA. Primers used in reverse transcription-PCR analysis of all genes examined are available upon request.

Glucose and Lipids Assays

Animals (n = 6 mice per group) were fasted overnight, and 200 μl of total blood removed from the saphenous vein. Blood samples were place on ice and centrifuged for 10 min at 800 rpm. Plasma glucose and lipids were determined by the National Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (University Cincinnati).

Zymosan Challenge

An inflammatory response was induced with 1 mg of zymosan per mouse, as described previously (Kolaczkowska et al., 2006). Zymosan (an insoluble carbohydrate from yeast cell wall) was freshly prepared (2 mg/ml) in sterile 0.9% NaCl, and 0.5 ml was i.p. injected into each mouse; controls received vehicle only. At the appropriate time points, each peritoneal cavity was washed with 5.0 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, and as much lavage fluid as possible was recovered. One portion (200 μl) was used for cell counting, and another (100 μl) taken for preparing histology slides. The amount of lavage fluid recovered per mouse was recorded so that, after centrifugation (3000g for 3 min), total peritoneal cell numbers (plus neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes) per mouse could be determined. For each group, four to eight mice were used.

Histology

From the oral BaP studies, bone marrow smears were obtained at sacrifice by dissecting the femurs free and removing muscle. After removal of the proximal and distal epiphyses, a tiny polyethylene tube was affixed to one end of the bone shaft; the marrow was gently blown onto a glass slide, and a second slide was used to squash the droplet of marrow onto the slide. The peritoneal cells after zymosan challenge, marrow smears and peripheral blood smears were air-dried on glass slides. All slides were stained with Wright-Giemsa (University Hospital Bone Marrow Lab). Differential counts of the peripheral blood and peritoneal exudate were performed. Percentage of different cell types was calculated, based on a minimum of 100 lymphocytes per sample.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance between groups was determined by analysis-of-variance among groups, Student's t test between groups, and Fisher's test between groups with very low frequencies. All assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate and repeated at least twice. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Sigma Plot (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA).

Results

Embryolethality

One overt phenotype of the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout was a noticeably decreased litter size (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we carried out eight different (female × male) crosses of various combinations (Table 1). In every case, Hardy-Weinberg distribution was skewed, showing less than the expected number of triple-knockout newborns; these data indicate that no particular maternal or paternal genotype favored viability of the triple-knockout pup. Sufficient numbers for each cross were generated to show P values of <0.05; when all breeding experiments were combined, the expected number (58.25 triple-knockout pups) was very significantly (P < 0.001) different from the observed number (30 viable pups).

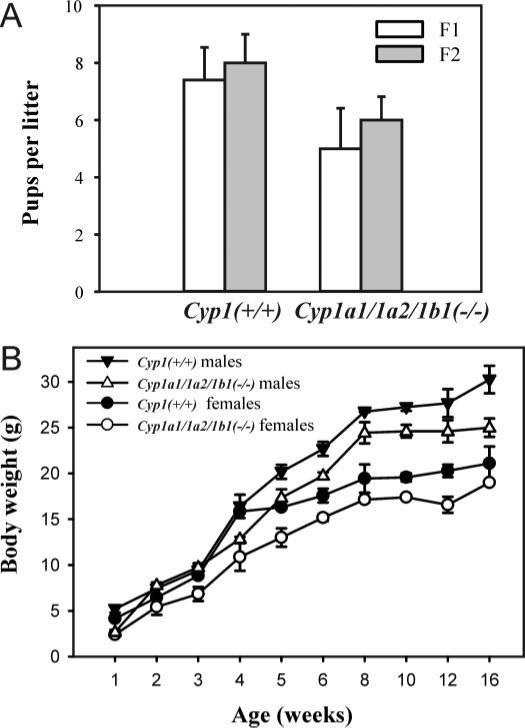

Fig. 1.

Comparison of litter size and weight gain in Cyp1(+/+) wild-type and Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout mice. A, number of pups per litter—viable at birth; more than half of those born alive died within the first 24 h. F1 denotes the generation when the triple-knockout genotype was initially obtained. F2 denotes litters derived from the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) × Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) intercross. B, weight gain in F1 male mice and F1 female mice, aged 1 through 16 weeks. The body weights of triple-knockout mice (males and females) were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than wild-type mice at age 5, 6, 10, and 12 weeks; the body weights of triple-knockout male mice (but not female mice) were significantly (P < 0.05) less than wild-type mice at age 16 weeks. Values and brackets represent means ± S.E., respectively (n = 4 to 5 litters in A; n = 6 mice in B).

TABLE 1. χ2 analysis of in utero lethality in triple-knockout pups.

Genetic crosses are designated as [mother genotype × father genotype]. A denotes Cyp1a1l1a2(+) wild-type allele, and a denotes Cyp1a1l1a2(−) knockout allele. B denotes Cyp1b1(+) wild-type allele, and b denotes Cyp1b1(−/−)knockout allele.

| Genetic Cross | Total Pups | TKO Pups |

χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | ||||

| Aabb × aaBb | 87 | 11 | 21.75 | 4.35 | <0.05 > 0.02 |

| Aabb × Aabb | 49 | 6 | 12.25 | 2.63 | <0.20 > 0.10 |

| aaBb × aaBb | |||||

| Totals of two above | 136 | 17 | 34 | 6.97 | <0.01 > 0.001 |

| Aabb × AaBb | 106 | 4 | 13.25 | 5.40 | <0.025 > 0.01 |

| AaBb × aaBb | |||||

| aabb × aaBb | 22 | 9 | 11 | 0.37 | <1.0 > 0.50 |

| aaBb × aabb | |||||

| Totals of all four above | 264 | 30 | 58.25 | 10.85 | <0.001 |

| aabb × aabba | 11 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 1.0 |

TKO, triple knockout.

Of the 30 triple-knockout F1 pups that survived, only two female mice and one male mouse lived to adulthood and were able to breed successfully.

It is noteworthy, however, that a small number of Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) pups survived the neonatal period (Fig. 1B) and lived long enough to produce offspring (Table 1). Although the litter size and weight gain (in both F1 male and female mice) was less in the triple-knockout than in wild-type, the triple-knockout mouse line (in a >99.8% C57BL/6J background) has now been sustained for >10 generations. We conclude that significant embryolethality, with incomplete penetrance, is a phenotype of the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) F1 mouse.

At what gestational age does the lethality occur? We examined four litters each of GD11, GD13, GD15, GD17 and GD19 (not shown) and found no significant differences in Hardy-Weinberg distribution. We conclude that in utero deaths, when they occur, happen in the F1 embryo—before GD11.

Birth Defects

Among 264 littermates that were not homozygous for both the Cyp1a1/1a2(−) and Cyp1b1(−) alleles, one Cyp1(+/+) wild-type and one Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) double-knockout exhibited hydrocephalus, but none showed hermaphroditism or cystic ovaries. In C57BL/6J mice (Kanno et al., 1987; Biddle et al., 1991), the “average” rates of occur-rence for hydrocephalus or hermaphroditism is one in ~500 to 1000 (~0.1–0.2%) and for cystic ovaries one in ~200 to 400 (~0.25–0.5%). Among 30 triple-knockout F1 pups, four exhibited hydrocephalus (P < 0.001), two hermaphroditism (P < 0.01), and two cystic ovaries (P < 0.01, all by Fisher's test). We conclude that significant increased risks of hydrocephalus, hermaphroditism and cystic ovaries, with incomplete penetrance, are phenotypes of the Cyp1 triple-knockout F1 mouse.

Pathology Report

Gross and microscopic evaluations of organs and tissues—including heart, lung, spleen, thymus, kidney, liver, cerebrum, cerebellum, eye, Harderian gland, testis, ovary, uterus, prostate, tongue, esophagus, pancreas, abdominal aorta, forestomach, glandular stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon—revealed no overt abnormalities in eight “normal”-appearing, healthy 6-week-old Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice. Mice with overt hydrocephalus showed severe hemorrhage of the meninges and cortex with necrosis of the cortex and dilation of the ventricles and died within a few days of birth. Overt hermaphrodites showed microscopic, as well as gross, evidence of Müllerian and Wolf-fian duct remnants. Cystic ovaries usually occurred bilaterally and were confirmed microscopically.

Effects of Dietary BaP

Previously it was shown that Cyp1a1(−/−) knockout mice ingesting BaP (125 mg/kg/day) die after ~28 days with severe immunosuppression, whereas Cyp1(+/+) wild-type mice for 1 year on this diet remain as healthy as untreated wild-type mice; it was concluded that BaP-induced intestinal and perhaps liver CYP1A1 are more important in detoxication than metabolic activation of oral BaP (Uno et al., 2004). On the other hand, oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) mice are “rescued” and appear similar to the wild-type phenotype; this was interpreted as the CYP1B1 enzyme in immune tissues being necessary and sufficient to metabolically activate BaP and cause immunosuppression (Uno et al., 2006). Cyp1a2(−/−), Cyp1b1(−/−), and Cyp1a2/1b1(−/−) respond to the oral BaP regimen similarly to (untreated or oral BaP-treated) wild-type mice. After 5 days of oral BaP, the total blood BaP of the Cyp1a1(−/−) and Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) is ~25 and ~75 times greater, respectively, than that of the wild-type mouse—demonstrating that the total body burden of an environmental toxicant can be independent of target-organ damage (Uno et al., 2006).

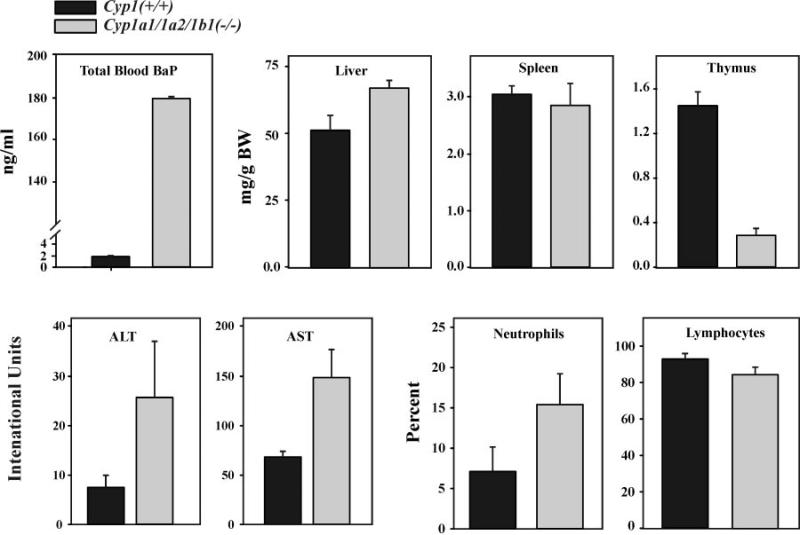

Figure 2 shows that blood BaP levels of the Cyp1 triple-knockout are ~90-fold higher than that of the wild-type. In the triple-knockout, compared with the wild-type, liver size is significantly greater and thymus weight smaller (P < 0.01); these parameters are prototypic signs of AHR activation and independent of CYP1 metabolism. The triple-knockout revealed elevated serum ALT and AST levels (P < 0.05), but no significant differences in spleen weight, or relative percentage of neutrophils or lymphocytes (Fig. 2). These findings are all consistent with mild damage in the oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−)—to approximately the same degree as that seen in the oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1b1(−/−) “rescued” double-knockout (Uno et al., 2006).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of wild-type and triple-knockout mice that have received oral BaP (125 mg/kg/day). Histograms of total blood BaP concentration; milligrams of liver, spleen, and thymus (wet weight) per gram of total body weight (BW); serum ALT and AST activities; and relative percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes in peripheral blood. Blood BaP levels were determined after 5 days of oral BaP; all other parameters were measured after 18 days of oral BaP. Values and brackets represent means ± S.E., respectively (n = 6 mice). Differences between the two genotypes were significant (P < 0.01) in liver and thymus weight and (P < 0.05) in ALT and AST activities. The BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) mouse was previously shown (Dragin et al., 2007) to exhibit severe immunosuppression similar to that seen in the BaP-treated Cyp1a1(−/−) mouse, whereas the BaP-treated Cyp1b1(−/−) responded similarly to the BaP-treated Cyp1(+/+) wild-type mouse (Uno et al., 2006). All untreated genotypes show no differences (except total blood BaP) from the BaP-treated wild-type (Uno et al., 2006).

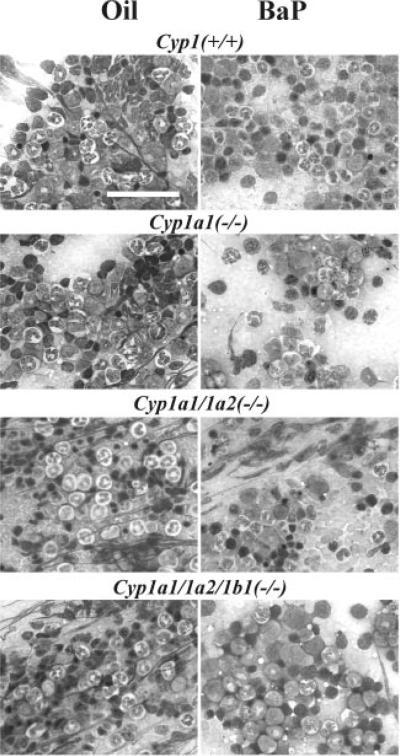

Histology of the bone marrow (Fig. 3) confirmed the Fig. 2 data. Whereas there was substantial bone marrow hypocellularity in oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1(−/−) and Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) mice, the oral BaP-treated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mouse was “rescued” and looked similar to that of the BaP-treated wild-type and the corn oil-treated control mice. Curiously, in the peripheral blood of the triple-knockout mice, there seemed to be an increased number of binucleated lymphocytes, in both untreated and oral BaP-treated animals.

Fig. 3.

Representative bone marrow histology, comparing untreated (oil) with oral BaP-treated wild-type (top) and triple-knockout (bottom) mice after 18 days of BaP. Marrows of the Cyp1a1(−/−) and Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) mice are included as positive controls, showing oral BaP-induced massive hypocellularity— especially with loss of lymphoid precursors. Marrows of untreated or oral BaP-treated Cyp1a2(−/−), Cyp1b1(−/−), and Cyp1a2/1b1(−/−) mice have previously been shown to exhibit the same normal cellularity as marrows of the Cyp1(+/+) wild-type, with or without oral BaP treatment (Uno et al., 2004, 2006). Bar, top left panel, 50 μm.

Urinary Metabolite Profiles

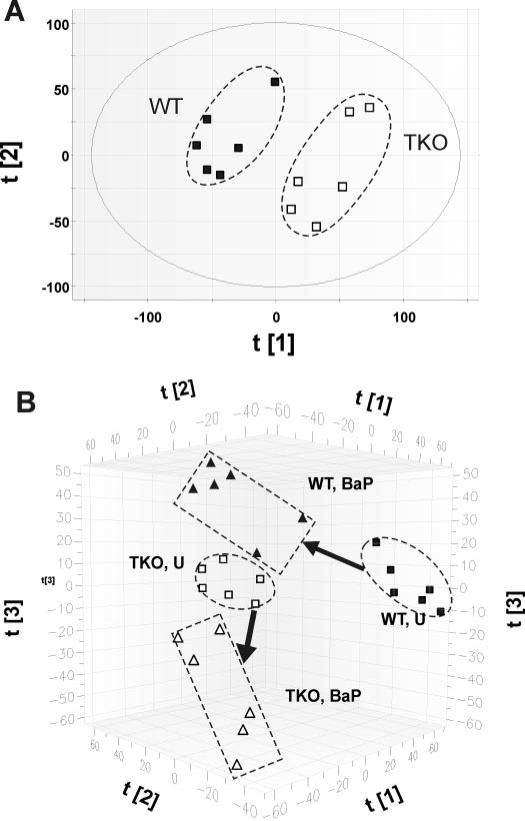

The phenotypic differences (described above) between untreated triple-knockout and wild-type mice imply the physiological importance of CYP1 enzyme-mediated endogenous metabolism. To examine this further, we compared, via LC-MS, the urinary metabolite profiles of untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1(+/+) mice. Principal components analysis revealed that the metabolite profiles from untreated triple-knockout and wild-type mice were distinctively separated in a two-component model (Fig. 4A), suggesting striking endogenous metabolism differences between the two genotypes.

Fig. 4.

Multivariate data analysis of urine samples from untreated (U) and oral BaP-treated wild-type (WT) and triple-knockout (TKO) mice. A, scores-scatter plot using the principal components analysis model to compare urine samples from the two untreated genotypes (n = 6). The t[1] and t[2] values represent the scores of each of the 12 samples in principal component 1 and 2, respectively; fitness (R2 value) of the model to the acquired dataset is 0.468, and predictive power (Q2 value) of the model is 0.184. B, three-dimensional scores-scatter plot of the partial least-squares-discriminant analysis model on the four groups of urine samples (n = 6). The t[1], t[2], and t[3] values represent the scores of each of the 24 samples in principal component 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The R2 value of the model to the acquired dataset is 0.859, and the Q2 value of the model is 0.743. The model was validated through the recalculation of R2 and Q2 values after the permutation of sample identities. Arrows indicate the metabolite profile directional changes, from untreated to that induced by BaP treatment.

Oral BaP-treated versus the untreated urinary metabolite profiles (Fig. 4B) were examined by partial least-squares-discriminant analysis of the LC-MS data. The distribution and clustering pattern of the four groups in this three-component model revealed that not only were there significant compositional differences among the four groups of urine samples, but also suggested that the triple-knockout and wild-type mice respond differently to BaP treatment—because the urinary metabolite profiles of Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1(+/+) mice shifted in distinctly different directions (i.e., from the untreated profiles to the oral BaP-treated profiles) (Fig. 4B, bold arrows).

Hepatic cDNA Expression Microarray Analysis

Because we saw differences in endogenous metabolism between the triple-knockout and wild-type (Fig. 4A), we conducted differential liver gene expression by microarray analysis; although some of this urinary metabolite profile probably reflects extrahepatic tissues, the vast majority of metabolism is found in liver.

If we used the simple “overly relaxed” P < 0.05 cut-off, there were 676 genes up-regulated and 437 genes down-regulated (i.e., comparing triple-knockout with wild-type mice). If we used the combination of the overly relaxed P < 0.05 plus a -fold change of ≥1.5 as the cut-off, there were 565 genes up- and 366 genes down-regulated. At the stringent FDR cut-off of ≤0.10, which gave P values of ≤0.00076, at least 89 genes were up- (Table 2) and 62 genes down-regulated (Table 3); the complete lists are available in Supplemental Data). The genes are ranked in order of -fold increase or decrease; Cox6b2 and Chrna4 showed the largest increases (7.09- and 5.47-fold, respectively) in the triple-knockout mice, whereas Snora65 and St3gal4 were the most decreased (7.58- and 5.32-fold, respectively). The GO categories (Table 4) for these 151 “most significantly perturbed” genes include lipid, steroid, and cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism; nucleosome and chromatin assembly; carboxylic and organic acid metabolism; metal-ion binding; and ion homeostasis.

TABLE 2. Microarray analysis of liver: selection of a subset of genes most significantly up-regulated in the untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−)versus untreated Cyp1(+/+) mouse.

These data exclude the NeoR pRev Tet-Off vector, which, because it is present in the genome of the triple-knockout mouse, is 12.7-fold “up-regulated”. Mouse mammary tumor virus, complete genome, was also excluded. False discovery rate is the adjusted P value. One out of 10 adjusted P values ≤0.10 would be expected to be a false positive. In this and subsequent tables, the P values are dependent on both the measurements of -fold change, as well as how consistent they are (variance). This is a partial list of 22 selected genes; the entire list of 89 up-regulated genes can be found in the Supplementary Data.

| Symbol | Gene Biochemical Name (Likely Function) | -Fold Increase | P | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox6b2a | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb, polypeptide 2 (electron transport) | 7.09 | <10−12 | <10−12 |

| Chrna4 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α-polypeptide-4 (extracellular ligand-gated ion channel activity, B cell activation) | 5.47 | <10−12 | <10−12 |

| Pwp1 | PWP1 homolog [S. cerevisiae] (activity in nucleus?) | 4.21 | 10−11 | 2 × 10−6 |

| Slc46a3 | Solute-carrier family 46, member 3 (unknown cation transporter) | 3.95 | 4 × 10−13 | 6 × 10−10 |

| Cd3e | CD3 antigen, ∊-polypeptide (lymphocyte activation) | 3.63 | 2 × 10−8 | 2 × 10−5 |

| Sult3a1a | Sulfotransferase, family 3A, member 1 (SO4 conjugation) | 3.62 | 10−11 | 2 × 10−8 |

| Acot11 | Acyl-coA thioesterase-11 (fatty acid metabolism, signal transduction) | 3.00 | 9 × 10−8 | 0.00005 |

| Mid1a | Midline-1 (ligase activity; metal-ion binding) | 2.93 | 2 × 10−8 | 0.00001 |

| Gstm3 | Glutathione S-transferase, μ3 (GSH conjugation) | 2.71 | 7 × 10−7 | 0.00009 |

| Cyp17a1 | Cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, member 1 (monooxygenation) | 2.70 | 2 × 10−7 | 0.00009 |

| Vldlra | Very low-density lipoprotein receptor (Ca2+-binding, lipid transporter, cholesterol metabolism) | 2.59 | 10−4 | 0.018 |

| Shank2 | SH3/ankyrin domain gene-2 (neuronal cell differentiation) | 2.52 | 2 × 10−4 | 0.018 |

| Cyp26a1 | Cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily A, member 1 (monooxygenation) | 2.47 | 3 × 10−6 | 0.0011 |

| Nqo1a | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (regulated by CYP1 activity) | 2.20 | 0.00004 | 0.0097 |

| Gstm5 | Glutathione S-transferase, μ5 (GSH conjugation) | 2.17 | <10−5 | 0.0011 |

| Ugt1a6ba | UDP glucuronosyltransferase, family 1, subfamily A, member 6b (glucuronide conjugation) | 2.15 | 0.00002 | 0.0062 |

| Ugt1a7ca | UDP glucuronosyltransferase, family 1, subfamily A, member 7c (glucuronide conjugation) | 2.07 | 0.00013 | 0.022 |

| Cyp2b20 | Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily B, member 20 (monooxygenation) | 1.97 | 0.00028 | 0.042 |

| Gstm7 | Glutathione S-transferase, μ7 (GSH conjugation) | 1.92 | 0.00055 | 0.067 |

| Insc | Inscuteable homolog [Drosophila melanogaster] (differentiation, developmental) | 1.92 | 0.00050 | 0.062 |

| Sidt2 | SID1 transmembrane family, member 2 (early embryo and postnatal expression) | 1.90 | 0.00073 | 0.079 |

| Ethe1 | Ethylmalonic encephalopathy-1 (hydrolase activity, metal-ion binding) | 1.88 | 0.00086 | 0.090 |

Confirmed via Q-PCR to be up-regulated.

TABLE 3. Microarray analysis of liver: selection of a subset of genes most significantly down-regulated in the untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−)versus untreated Cyp1(+/+) mouse.

These data exclude the Cyp1a1, Cyp1a2, and Cyp1b1 genes, which, because they were genetically ablated, are strikingly (>95-fold) “down-regulated”. Interestingly, one of two Cyp1b1 primer sets that exist in the mouse 70-mer MEEBO oligonucleotide library was detectable and showed up-regulation, but this is interpreted as a genomic transcript that had not been ablated in generating the Cyp1b1(−/−)knockout mouse line (Buters et al., 1999). There were six murine virus genomes significantly (FDR ≤0.10) down-regulated, which were also excluded. False discovery rate is the adjusted P value. One out of ten adjusted P values ≤0.10 would be expected to be a false positive. This is a partial list of 22 selected genes; the entire list of 62 down-regulated genes can be found in the Supplementary Data.

| Symbol | Gene Biochemical Name (Likely Function) | -Fold Decrease | P | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snora65 | Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box-65 (part of ribonucleoprotein complex) | 7.58 | <10−16 | <10−12 |

| St3gal4a | ST3 β-galactoside α2,3-sialyltransferase (amino-acid glycosylation) | 5.32 | <10−16 | <10−12 |

| Cachd1 | Cache domain-containing-1 (Ca2+-ion binding) | 4.75 | 9 × 10−16 | 2 × 10−12 |

| Rgs16 | Regulator of G protein signaling-16 (GTPase activator, signal transduction) | 4.28 | 10−16 | 2 × 10−11 |

| Cbx3 | Chromobox homolog-3 [Drosophila melanogaster HP1-γ] (chromatin-binding) | 3.89 | 10−11 | 5 × 10−7 |

| Mt2a | Metallothionein-2 (metal-ion binding) | 3.66 | 5 × 10−12 | 7 × 10−9 |

| Mt1a | Metallothionein-1 (metal-ion binding) | 3.61 | 2 × 10−13 | 3 × 10−10 |

| Igfbp2 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 (growth-factor binding) | 3.33 | 2 × 10−10 | 2 × 10−7 |

| Rbbp4 | Retinoblastoma-binding protein-4 (cell cycle, chromatin modification) | 2.73 | 2 × 10−7 | 0.0001 |

| Ccnd1 | Cyclin D1 (cell cycle, protein kinase regulator) | 2.54 | 4 × 10−9 | 4 × 10−6 |

| Etohd3 | Ethanol decreased-3 (activity in blastocyst) | 2.35 | 0.00023 | 0.037 |

| Il28ra | Interleukin-28 receptor-α (inflammatory signaling pathways) | 2.29 | 0.00004 | 0.0084 |

| Marco | Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (PO4 transport) | 2.20 | 0.00004 | 0.0098 |

| Snora70 | Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box-70 (part of ribonucleoprotein complex) | 2.19 | 0.00004 | 0.0098 |

| Qk | Quaking (axon ensheathment, nucleic-acid binding) | 2.15 | 0.00008 | 0.016 |

| Wee1 | wee-1 homolog [Saccharomyces pombe] (cell cycle, kinase activity) | 2.14 | 0.00007 | 0.015 |

| Ifi27 | Interferon, α-inducible protein 27 (response to virus) | 2.10 | 0.00007 | 0.014 |

| Peci | Peroxisomal Δ3,Δ2-enoyl-coA isomerase (peroxisome assembly, biogenesis) | 2.10 | 0.00007 | 0.015 |

| Trpm8b | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 8 (Ca2+ channel activity) | 2.08 | 0.00064 | 0.074 |

| Slco1a1b | Solute-carrier organic anion transporter family 1, member 1 (organic anion transport) | 2.02 | 0.00010 | 0.018 |

| Socs2a | Suppressor of cytokine-signaling-2 (chemokine signal transduction, fat cell differentiation) | 1.97 | 0.00035 | 0.048 |

| Mt4a | Metallothionein-4 (metal-ion binding) | 1.91 | 0.00067 | 0.076 |

Confirmed twice via Q-PCR to be down-regulated.

Checked twice by Q-PCR and not found to be statistically significantly down-regulated.

TABLE 4. Gene ontology (GO) classes in microarray analysis of liver: comparison of the untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−)with the untreated Cyp1(+/+) with mouse line.

GO classification of genes most perturbed (up- and down-regulated, combined); 140 GO biological process categories were tested. Those categories with an FDR <0.10 are listed. False discovery rate is the adjusted P value. One out of ten adjusted P values ≤0.10 would be expected to be a false positive.

| Class | Gene Count | P | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid biosynthesis | 16 | <10−5 | 0.0015 |

| Steroid biosynthesis | 15 | 0.00004 | 0.0067 |

| Cellular lipid metabolism | 22 | 0.00006 | 0.0083 |

| Nucleosome | 8 | 0.00008 | 0.0095 |

| Lipid metabolism | 24 | 0.00011 | 0.011 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 29 | 0.00013 | 0.012 |

| Steroid metabolism | 11 | 0.00019 | 0.012 |

| Carboxylic acid metabolism | 21 | 0.00020 | 0.012 |

| Organic acid metabolism | 21 | 0.00020 | 0.012 |

| Cofactor binding | 9 | 0.00024 | 0.013 |

| Lyase activity | 12 | 0.00027 | 0.013 |

| Xenobiotic metabolism | 9 | 0.00050 | 0.023 |

| Cholesterol biosynthesis | 5 | 0.00067 | 0.029 |

| Glutathione transferase activity | 5 | 0.00080 | 0.030 |

| Sterol biosynthesis | 5 | 0.0011 | 0.040 |

| Alcohol metabolism | 13 | 0.0013 | 0.042 |

| Intramolecular oxidoreductase activity | 6 | 0.0013 | 0.042 |

| Nucleosome assembly | 7 | 0.0013 | 0.042 |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 7 | 0.0028 | 0.079 |

| Chromatin | 9 | 0.0029 | 0.079 |

| Chromatin assembly or disassembly | 8 | 0.0029 | 0.079 |

| Chromatin assembly | 7 | 0.0030 | 0.079 |

| Transferase activity (alkyl or aryl) | 6 | 0.0031 | 0.079 |

| Cholesterol metabolism | 6 | 0.0036 | 0.086 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 8 | 0.0037 | 0.086 |

| Isomerase activity | 9 | 0.0041 | 0.089 |

Because we saw increased gene expression in many lipid pathways for the untreated triple-knockout compared with the wild-type mice, we examined these pathways further in fasting animals (n = 6 per group). Comparing the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) with Cyp1(+/+), we found a trend of decreases in the triple-knockout mouse but no statistically (P > 0.05) significant differences in serum cholesterol (129 ± 8.9 versus 132 ± 12 mg/dL), triglycerides (35.5 ± 10 versus 41.7 ± 2.7 mg/dL), phospholipids (152 ± 1.4 versus 159 ± 4.4 mg/dL), nonesterified fatty acids (0.79 ± 0.03 versus 0.89 ± 0.09 mEq/liter), or glucose (116 ± 5.2 versus 145 ± 33 mg/dL), respectively.

Hepatic mRNA Expression by Q-PCR Analysis

To substantiate the microarray expression data, we performed Q-PCR analysis on 22 genes (Table 5) to determine whether their mRNA levels could be confirmed as up- or down-regulated—as had been determined by microarray expression. As expected, wild-type mice carried the three Cyp1 genes, which were TCDD-inducible, whereas the triple-knockout had no detectable normal-length transcripts (Table 3, footnote). Cox6b2, Mid1, and Vldlr expression was up-regulated in the microarray (Table 2), and this was confirmed by Q-PCR (Table 5). Nqo1, Ugt1a6b, and Ugt1a7c are TCDD-inducible genes, and thus we analyzed those genes by Q-PCR in both untreated and oral BaP-treated mice; mRNA levels of all three genes were significantly elevated in the untreated triple-knockout compared with the untreated wild-type.

TABLE 5. Expression of hepatic mRNA, examining genes different between untreated or TCDD-treated wild-type and triple-knockout mice.

TCDD is regarded as the prototypical Cyp1 inducer and, when given intraperitoneally as a 15 μg/kg dose, usually induces the hepatic CYP1 mRNA and protein levels to the same maximal levels as intraperitoneal BaP at a 100 mg/kg dose. Values are expressed as the means ± S.E. mRNA levels, relative to β-actin mRNA (n = 6).

| Gene name |

Cyp1(+/+) |

Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) |

TKO/WT (Microarray) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | TCDD | U | TCDD | ||

| Cyp1a1 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 6,010 ± 51a | ND | ND | NA |

| Cyp1a2 | 450 ± 39 | 2,200 ± 180a | ND | ND | NA |

| Cyp1b1 | 6.2 ± 0.59 | 62 ± 6.3a | ND | ND | NA |

| Cox6b2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.39 ± 0.1a | 39 ± 0.1b | 13 ± 0.2a | +7.09 |

| Sult3a1 | 1.00 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.2a | 0.90 ± 0.1 | 0.29 ± 0.2a | +3.62 |

| Mid1 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.7b | 0.87 ± 0.03a | +2.93 |

| Vldlr | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.1a | 3.8 ± 0.2b | 2.8 ± 0.02a | +2.59 |

| Nqo1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.3a | 2.0 ± 0.2b | 3.7 ± 0.4a | +2.20 |

| Ugt1a6b | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.88 ± 0.3a | 2.4 ± 0.4b | 4.6 ± 0.4a | +2.15 |

| Ugt1a7c | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4a | 4.0 ± 0.2b | 4.6 ± 0.4 | +2.07 |

| Gsta1 | 0.83 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.06a | 0.29 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.1a | NA |

| Hmox1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.43 ± 0.1a | 0.15 ± 0.1b | 0.17 ± 0.4 | NA |

| Gclc | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.87 ± 0.3 | NA |

| Gclm | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.2 | 0.60 ± 0.3 | NA |

| St3gal4 | 1.2 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.1a | 0.29 ± 0.2b | 0.69 ± 0.1a | −5.86 |

| Mt1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.35 ± 0.2a | 0.21 ± 0.1b | 0.24 ± 0.4 | −3.61 |

| Mt2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.09 ± 0.4a | 0.41 ± 0.2b | 0.56 ± 0.4 | −3.66 |

| Mt4 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.4a | 0.78 ± 0.2 | 0.48 ± 0.2 | −1.91 |

| Trpm8 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.4a | 0.94 ± 0.4 | 0.60 ± 0.2 | −2.08 |

| Slco1a1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.2a | 0.78 ± 0.2 | 0.20 ± 0.3 | −2.02 |

| Socs2 | 1.00 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.2a | 0.90 ± 0.1 | 0.29 ± 0.2a | −1.97 |

| Ccne1 | 1.0 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.3a | 0.22 ± 0.1b | 0.08 ± 0.3 | −1.56c |

N.D., not detectable by Q-PCR; N.A., not applicable.

P < 0.05, comparing Q-PCR measurements of liver RNA from TCDD-treated with untreated (U) controls of same genotype.

P < 0.05, comparing Q-PCR in Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1/(−/−)versus Cyp1(+/+) mice.

Ccne1, quite significant after two dye flips, fell beyond the FDR ≤0.10 significance cutoff after three dye flips; yet, by way of Q-PCR this mRNA was significantly decreased in untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1/(−/−) compared with untreated Cyp1(+/+) mice.

Expression of the St3gal4, Ccne, Trpm8 and Slco1a1 genes were down-regulated in the untreated triple-knockout (Table 4); the former two were verified by Q-PCR analysis (Table 5); in the cases of Trpm8 and Slco1a1, the trend was downward but would require a larger sample size to prove these genes are down-regulated, as had been found in the microarray data.

Mt1, Mt2, and Mt4 expression was down-regulated in the untreated triple-knockout (Table 4), and this was confirmed by Q-PCR (Table 5). Because the Mt genes are up-regulated under conditions of oxidative stress, we tested three additional oxidative-response genes: Hmox1 and Gclm were down-regulated in untreated triple-knockout mice, but Gclc was not (Table 5). Curiously, TCDD treatment of Cyp1(+/+) mice caused significant down-regulation in the Hmox1, Mt1, Mt2, and Mt4 genes.

Zymosan-Induced Peritonitis

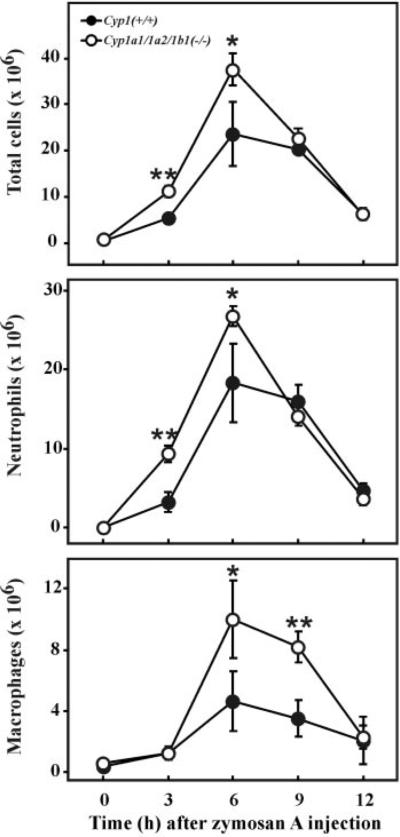

Members of the CYP1, CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4 families have been shown to be involved in eicosanoid biosynthesis and metabolism (Nebert and Russell, 2002). Several dozen of the 151 “most significantly perturbed genes” (Supplemental Data) are involved in lipid mediator and inflammation pathways. For these reasons, we therefore decided to compare the inflammatory response of Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice with Cyp1(+/+) mice. No differences in peritoneal cells (total cell numbers, or numbers of neutrophils and macrophages) between the two geno-types were found in untreated animals (Fig. 5). After zymosan intraperitoneal injection, however, the triple-knockout displayed an exaggerated response (peaking at 6 h) compared with that in the wild-type, with significant increases in neutrophil, macrophage and total cell infiltration into the peritoneal cavity.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic analysis of zymosan-induced peritonitis in wild-type and triple-knockout mice. Top, total number of peritoneal cells. *P = 0.02. **, P = 0.0002. Middle, total number of peritoneal neutrophils. *P = 0.02. **, P = 0.0001. Bottom, total number of macrophages. *P = 0.04. **, P = 0.002. In untreated mice at time 0, Cyp1(+/+) and Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mice exhibited 1.14 ± 0.12 × 106 and 1.25 ± 0.44 × 106, respectively (P = 0.62). Values are expressed as means ± S.E., using Student's two-tailed t test (n = four to eight mice per time-point per group).

Discussion

In this study, we have described multiple outcomes in the triple-knockout F1 mouse—which has all three Cyp1 genes ablated—compared with wild-type mice: embryolethality before GD11; significantly increased risk of hydrocephalus, hermaphroditism, and cystic ovaries; striking differences in urinary endogenous metabolite profiles detected by LC-MS analysis; dramatic differences in urinary metabolite profiles detected by LC-MS analysis after oral BaP treatment; at least 89 and 62 genes very significantly up- and down-regulated, respectively. The gene categories most perturbed were lipid, steroid, and cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism; nucleosome and chromatin assembly; carboxylic and organic acid metabolism; metal-ion binding; and ion homeostasis. The triple-knockout also showed an exaggerated response to zymosan-induced peritonitis.

CYP1-Mediated Eicosanoid Metabolism

All of the above-described phenotypic alterations may well be the result of alterations in the production, catabolism and/or function of eicosanoids: bioactive mediators derived from arachidonic acid via ω-6 fatty acids (including prostaglandins, prostacyclins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, hepoxilins, and lipoxins) and bioactive mediators derived from eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid via ω-3 fatty acids, (including resolvins, docosatrienes, eoxins, and neuroprotectins). Eicosanoids exert largely unappreciated complex control over virtually all physiological processes: inflammation (Chiang et al., 2005; Leone et al., 2007; Mariotto et al., 2007; Serhan, 2007; Seubert et al., 2007), resolution phase of inflammation (Serhan, 2007), innate immunity (Ballinger et al., 2007), cardiopulmonary and vascular functions (Moreland et al., 2007; Seubert et al., 2007), angiogenesis (Fleming, 2007; Inceoglu et al., 2007), sensor of vascular pO2 (Sacerdoti et al., 2003), bowel motility (Proctor et al., 1987), regulation of lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity (Larsen et al., 2007; Nigam et al., 2007; Spector and Norris, 2007), central nervous system functions (Miyata and Roman, 2005; Jakovcevic and Harder, 2007), modulation of non-neuropathic pain (Inceoglu et al., 2007), neurohormone secretion and release (Inceoglu et al., 2007), fibrinolysis (Westlund et al., 1991; Jiang, 2007), inhibition of platelet aggregation (Westlund et al., 1991; Jiang, 2007), reproductive success (Cha et al., 2006; Weems et al., 2006), blastocyst implantation (Cha et al., 2006; Kennedy et al., 2007), early embryonic as well as fetal development (Cha et al., 2006), stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation (Chen et al., 1998), G protein-signaling (Inceoglu et al., 2007), modulation of nuclear factor κB (Inceoglu et al., 2007), cation and anion homeostasis (Sacerdoti et al., 2003; Hao and Breyer, 2007; Inceoglu et al., 2007; Nüsing et al., 2007; Plant and Strotmann, 2007; Spector and Norris, 2007; Xiao, 2007), and cell division, proliferation, and chemotaxis (Fleming, 2007; Inceoglu et al., 2007; Medhora et al., 2007; Nieves and Moreno, 2007; Spector and Norris, 2007).

Eicosanoids can be quickly released by most cell types (often stored in red blood cells) and act as autocrine or paracrine mediators, which are then rapidly inactivated. Eicosanoid biosynthesis involves metabolism by the 5-, 12-, and 15-lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenases-1 and -2—as well as most, if not all, CYP1, CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4 enzymes. These same P450 enzymes also participate in the rapid inactivation/degradation of eicosanoids. We propose that the absence of all three CYP1 enzymes in the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mouse perturbs the following: reproductive success; normal implantation and early embryogenesis, leading to a greater incidence of embryolethality (Table 1); proper development of ventricle valves in the central nervous system, leading to hydrocephalus; physiological differentiation of the Müllerian and Wolffian ducts, causing hermaphroditism; normal development of the ovary during fetogenesis, leading to cystic ovaries; many of the genes in the GO categories of lipid, steroid, and cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism; nucleosome and chromatin assembly; carboxylic and organic acid metabolism; metal-ion binding; ion homeostasis (Table 4); and the pro-inflammatory and -resolution processes—leading to an exaggerated response to zymosan-induced peritonitis (Fig. 5).

In fact, the Ahr(−/−) knockout mouse displays patent ductus venosus and other arteriovenous-shunt problems (Lahvis et al., 2005), along with immune dysregulation (Fernandez-Salguero et al., 1995), and increased susceptibility to infection (Shi et al., 2007)—probably caused also by perturbation of eicosanoid function. Indeed, six different prostaglandins (albeit at relatively high concentrations) have been shown to activate the AHR and induce the CYP1 enzymes (Seidel et al., 2001). Furthermore, a differential gene-expression microarray between Ahr(−/−) and wild-type mice (Yoon et al., 2006) shows perturbation of genes in all the categories listed above that reflect eicosanoid functions. Whereas the Ahr(−/−) mouse has no functional AHR and therefore all downstream genes regulated by the AHR would be affected, the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mouse has a functional AHR but has just the three CYP1 enzyme functions genetically removed. Therefore, using these two mouse lines, we should be able to distinguish between AHR-dependent functions and AHR-regulated CYP1-dependent functions in the intact mouse.

Microarray cDNA Expression Data

The mouse 70-mer Mouse Exonic Evidence-Based Oligonucleotide (MEEBO) library version 1.05 has 25,130 genes, which is supposed to cover nearly the entire genome. In several dozen instances, there are two sets of primers for the same gene, which serves as a rigorous check on the accuracy of the expression data. However, with only three replicates (Supplemental Data), we realize that we could still be missing dozens of additional relevant genes having important differential expression differences between untreated Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) and Cyp1(+/+) mice.

The Cox6b2 gene is ~7-fold higher in triple-knockout than in wild-type mice (Tables 2 and 5). Cox6b2 transcripts are ubiquitous (Taanman et al., 1990). O2 consumption is known to increase in liver mitochondria prepared from Ahr(−/−) mice but not from Cyp1a1(−/−) or Cyp1a2(−/−) mice (Senft et al., 2002). TCDD decreases the cytochrome oxidase rate constant, but increases O2 consumption and increases coenzyme Q-cytochrome c reductase activity (Shertzer et al., 2006). Could it be that the mitochondrial CYP1 enzymes are part of the cytochrome-oxidase complex, which divert, or supply, electrons from (or to) O2? Hence, if all three mitochondrial CYP1 enzymes are absent, then the cytochromeoxidase complex might compensate by a striking elevation of the COX6B2 subunit.

The Stegal4 gene is ~5.3-fold lower in untreated triple-knockout than in wild-type mice (Tables 3 and 5). Sialyltransferases modulate the increased expression of surface-sialylated structures during the generation of dendritic cells derived from monocytes (Videira et al., 2008), which is likely to be associated with eicosanoid-mediated changes in various cell functions.

The Socs2 gene, whose hepatic expression is down-regulated ~2-fold in the triple-knockout (Tables 3 and 5), is of special interest. Both endogenous and exogenous ligands have been shown to up-regulate SOCS2 expression. TCDD has been shown to drive SOCS2 expression in lymphocytes in an AHR-dependent fashion (Boverhof et al., 2004). Inhibition of dendritic cell pro-inflammatory cytokine production by lipoxins (which are pro-resolution eicosanoids) is dependent on AHR-driven up-regulation of SOCS2 expression (Machado et al., 2006). The decreased expression of SOCS2 observed in the triple-knockout suggests an obvious potential mechanism for the exaggerated inflammatory response seen in response to zymosan challenge, as well as the possibility that these CYP1 enzymes play an important role in the generation of endogenous eicosanoid ligands for the AHR. Activation of the AHR by the lipoxins triggers expression of SOCS2, which causes the ubiquitinylation of tumor necrosis factor α-receptor-association factors encoded by each of seven Traf genes in the mouse.

The [Ah] Gene Battery

The Nqo1, Ugt6b, and Ugt7c genes were 2.20-, 2.15-, and 2.07-fold increased, respectively (Tables 2 and 5). These data are particularly intriguing, because various cell culture studies (Nebert et al., 2000b) had shown that several members of the [Ah] gene battery become up-regulated when CYP1 enzyme activity is absent; moreover, addition of a mouse CYP1A1 or human CYP1A2 expression vector restores expression of these [Ah] member genes to their low basal wild-type phenotype status (RayChaudhuri et al., 1990). Long ago, these findings were interpreted as CYP1 enzymes being required to degrade a putative endogenous ligand of the AHR; when all CYP1 activity is extinguished, the AHR is highly activated (Robertson et al., 1987). This hypothesis has been supported experimentally by studies using CYP1- and AHR-deficient cells in culture (Chang and Puga, 1998) and by studies comparing the lung of Ahr(−/−) versus Ahr(+/+) mice (Chiaro et al., 2007).

Curiously, a number of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes (XMEs) are overexpressed in the triple-knockout (Table 2): all three Gstm genes; the sulfotransferase Sult3a1; Cyp17a1 (important in steroid biosynthesis), Cyp2b20, and Cyp26a1 (important in metabolism of the morphogen retinoic acid); and two Ugt1 genes. Feedback inhibition and interactions of XMEs and their XME-related transporters during inflammation and tumorigenesis have been reviewed (Nebert and Dalton, 2006; Zhou et al., 2006). It is tempting to speculate that some (or all) of these genes might also be members of the [Ah] gene batter.

Incomplete Penetrance

Finally, we found embryolethality—as well as the risk of the hydrocephalus, hermaphroditism, and cystic ovaries—to be inherited as incomplete penetrance traits (Table 1, Fig. 1), despite the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) genotype having been placed directly into a >99.8% C57BL/6J genetic background. Rather than explaining incomplete penetrance as being the result of a heterogeneous genetic background, therefore, it is more likely to be explained by redundancy; i.e., the AHR-controlled basal and inducible CYP1 expression levels and their downstream functions must overlap with expression levels and functions of other genes and gene products.

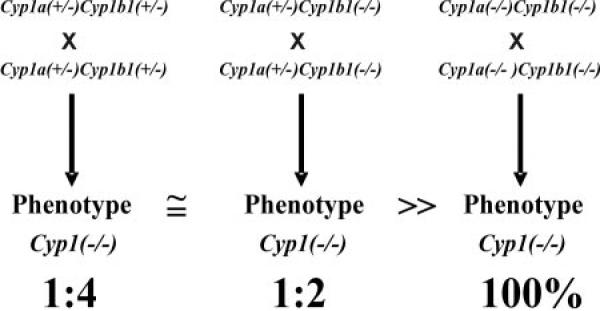

Most interestingly, as we have continued to breed the triple-knockout F1 homozygote survivors for more than 10 generations, the embryolethality and birth defects have disappeared. Note the trend of more pups per litter, even between the F1 and F2 generations (Fig. 1A). We believe this can be explained by natural selection: as the healthiest animals survive and are chosen for breeding in the next generation—genetic and epigenetic factors associated with embryolethality and birth defects give way to those associated with improved viability and high reproductive performance. Accordingly, we are maintaining in our mouse colony the double-heterozygote and single-heterozygote as mating pairs (Fig. 6); it is very clear that pups from these two breeding combinations provide animals with greatly affected phenotypes, compared with that seen in pups derived from the continued inbreeding of homozygous triple-knockout mice. To our knowledge, this effect of natural selection during subsequent brother × sister matings (when one sees F1 embryolethality or other phenotypes having incomplete penetrance) has not been considered previously in knockout-mouse studies. We are certain, however, that this must commonly occur.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram to illustrate that those triple-knockout pups derived from the double-heterozygote mating (left) and from the single-heterozygote mating (middle) will show incomplete-penetrance traits that differ dramatically from pups derived from the continual double-homozygote mating (right) (i.e., maintenance of the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) triple-knockout mouse line).

Future Studies

The microarray expression data described herein represent a gold mine of opportunities for determining the various downstream genes and their functions—when all three Cyp1 genes have been ablated. Future comparisons between the Ahr(−/−) mouse and the Cyp1 triple-knockout mouse should uncover new exciting findings. We propose that studies such as these will provide us with a greater understanding of AHR-dependent versus AHR-regulated CYP1-dependent eicosanoid biosynthesis and degradation, as well as their concomitant autocrine and paracrine functions. The Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1(−/−) mouse line is available to any investigator who might be interested.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Howard Shertzer and other colleagues for valuable discussions and critical readings of the manuscript. We appreciate very much the earlier help of Shige Uno and Tim Dalton in creating the Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) double-knockout line. We are also grateful to Mario Medvedovic for statistical advice and especially to Marian L. Miller for participation in histology, microscopy, as well as all graphics.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01-ES08147 (D.W.N.), R01-ES014403 (D.W.N.), and P30-ES06096 (M.L.M., C.L.K., and D.W.N.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CYP, P450

cytochrome P450

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- BaP

benzo[a]pyrene

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-pdioxin

- GD

gestational day

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- QTOF

quantitative time-of-flight

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GO

gene ontology

- Q-PCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- XME

xenobiotic-metabolizing enzyme

- SOCS2

suppressor of cytokine-signaling-2

Footnotes

N.D. and Z.S. contributed equally to this study.

These data were presented at the 27th Annual Meeting of the Society of Toxicology; 27 March 2007, Charlotte, NC.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm. aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Ballinger MN, McMillan TR, Moore BB. Eicosanoid regulation of pulmonary innate immunity post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2007;55:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle FG, Eales BA, Nishioka Y. A DNA polymorphism from five inbred strains of the mouse identifies a functional class of domesticus-type Y chromosome that produces the same phenotypic distribution of gonadal hermaphrodites. Genome. 1991;34:96–104. doi: 10.1139/g91-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boverhof DR, Tam E, Harney AS, Crawford RB, Kaminski NE, Zacharewski TR. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induces suppressor-of-cytokine-signaling-2 in murine B cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1662–1670. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buters JT, Sakai S, Richter T, Pineau T, Alexander DL, Savas U, Doehmer J, Ward JM, Jefcoate CR, Gonzalez FJ. Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 determines susceptibility to 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha YI, Solnica-Krezel L, DuBois RN. Fishing for prostanoids: deciphering the developmental functions of cyclooxygenase-derived prostaglandins. Dev Biol. 2006;289:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Puga A. Constitutive activation of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:525–535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JK, Falck JR, Reddy KM, Capdevila J, Harris RC. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and their sulfonimide derivatives stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation and induce mitogenesis in renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29254–29261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory circuitry: lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor ALX. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaro CR, Patel RD, Marcus CB, Perdew GH. Evidence for an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated cytochrome P450 autoregulatory pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1369–1379. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton TP, Dieter MZ, Matlib RS, Childs NL, Shertzer HG, Genter MB, Nebert DW. Targeted knockout of Cyp1a1 gene does not alter hepatic constitutive expression of other genes in the mouse [Ah] battery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:184–189. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database For Annotation, Visualization, And Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragin N, Uno S, Wang B, Dalton TP, Nebert DW. Generation of “humanized” hCYP1A1_1A2_Cyp1a1/1a2(−/−) mouse line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Salguero P, Pineau T, Hilbert DM, McPhail T, Lee SS, Kimura S, Nebert DW, Rudikoff S, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science. 1995;268:722–726. doi: 10.1126/science.7732381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, cell signaling and angiogenesis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Falcón MS, Gonzalez-Amigo S, Lage-Yusty MA, Lopez de Alda Villaizan MJ, Simal-Lozano J. Determination of benzo[a]pyrene in lipid-soluble liquid smoke (LSLS) by HPLC-FL. Food Addit Contam. 1996;13:863–870. doi: 10.1080/02652039609374473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao CM, Breyer MD. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of lipid mediators in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MA, Clark J, Ireland A, Lomax J, Ashburner M, Foulger R, Eilbeck K, Lewis S, Marshall B, Mungall C, et al. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inceoglu B, Schmelzer KR, Morisseau C, Jinks SL, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition reveals novel biological functions of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcevic D, Harder DR. Role of astrocytes in matching blood flow to neuronal activity. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;79:75–97. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)79004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. Erythrocyte-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Nakamura T, Jain VK, Sugimoto T. An experimental model of communicating hydrocephalus in C57 black mouse. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1987;86:111–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01402294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TG, Gillio-Meina C, Phang SH. Prostaglandins and the initiation of blastocyst implantation and decidualization. Reproduction. 2007;134:635–643. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Kwack SJ, Lee BM. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidant enzymes, and benzo[a]pyrene quinones in the blood of rats treated with benzo[a]pyrene. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;127:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaczkowska E, Chadzinska M, Scislowska-Czarnecka A, Plytycz B, Opdenakker G, Arnold B. Gelatinase B/matrix metalloproteinase-9 contributes to cellular infiltration in a murine model of zymosan peritonitis. Immunobiology. 2006;211:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahvis GP, Pyzalski RW, Glover E, Pitot HC, McElwee MK, Bradfield CA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is required for developmental closure of the ductus venosus in the neonatal mouse. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:714–720. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BT, Campbell WB, Gutterman DD. Beyond vasodilatation: non-vasomotor roles of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the cardiovascular system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone S, Ottani A, Bertolini A. Dual acting anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:265–275. doi: 10.2174/156802607779941341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang HC, Li H, McKinnon RA, Duffy JJ, Potter SS, Puga A, Nebert DW. Cyp1a2(−/−) null mutant mice develop normally but show deficient drug metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1671–1676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado FS, Johndrow JE, Esper L, Dias A, Bafica A, Serhan CN, Aliberti J. Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered lipoxin are SOCS-2 dependent. Nat Med. 2006;12:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nm1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotto S, Suzuki Y, Persichini T, Colasanti M, Suzuki H, Cantoni O. Cross-talk between NO and arachidonic acid in inflammation. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1940–1944. doi: 10.2174/092986707781368531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan BJ, Bradfield CA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor sans xenobiotics: endogenous function in genetic model systems. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:487–498. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhora M, Dhanasekaran A, Gruenloh SK, Dunn LK, Gabrilovich M, Falck JR, Harder DR, Jacobs ER, Pratt PF. Emerging mechanisms for growth and protection of the vasculature by cytochrome P450-derived products of arachidonic acid and other eicosanoids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata N, Roman RJ. Role of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) in vascular system. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2005;41:175–193. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.41.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland KT, Procknow JD, Sprague RS, Iverson JL, Lonigro AJ, Stephenson AH. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 participate in 5,6-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-induced contraction of rabbit intralobar pulmonary arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:446–454. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Dalton TP. The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in endogenous signalling pathways and environmental carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:947–960. doi: 10.1038/nrc2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Dalton TP, Okey AB, Gonzalez FJ. Role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of the CYP1 enzymes in environmental toxicity and cancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23847–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Dalton TP, Stuart GW, Carvan MJ., III “Gene-swap knock-in” cassette in mice to study allelic differences in human genes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000a;919:148–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Roe AL, Dieter MZ, Solis WA, Yang Y, Dalton TP. Role of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor and [Ah] gene battery in the oxidative stress response, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000b;59:65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Russell DW. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet. 2002;360:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Zeldin DC, Hoffman SM, Maltais LJ, Wain HM, Nebert DW. Comparison of cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes from the mouse and human genomes, including nomenclature recommendations for genes, pseudogenes and alternative-splice variants. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves D, Moreno JJ. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids induce growth inhibition and calpain/caspase-12 dependent apoptosis in PDGF-cultured 3T6 fibroblast. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1979–1988. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam S, Zafiriou MP, Deva R, Ciccoli R, Roux-Van der MR. Structure, biochemistry and biology of hepoxilins: an update. FEBS J. 2007;274:3503–3512. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsing RM, Schweer H, Fleming I, Zeldin DC, Wegmann M. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids affect electrolyte transport in renal tubular epithelial cells: dependence on cyclooxygenase and cell polarity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F288–F298. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00171.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TD, Strotmann R. TRPV4. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;179:189–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor KG, Falck JR, Capdevila J. Intestinal vasodilation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: arachidonic acid metabolites produced by a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Circ Res. 1987;60:50–59. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RayChaudhuri B, Nebert DW, Puga A. The murine Cyp1a1 gene negatively regulates its own transcription and that of other members of the aromatic hydrocarbon-responsive [Ah] gene battery. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1773–1781. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-12-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Identifying differentially expressed genes using false discovery rate-controlling procedures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JA, Hankinson O, Nebert DW. Autoregulation plus positive and negative elements controlling transcription of genes in the [Ah] battery. Chem Scripta. 1987;27A:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JR, Felton JS, Levitt RC, Thorgeirsson SS, Nebert DW. Relationship between “aromatic hydrocarbon responsiveness” and the survival times in mice treated with various drugs and environmental compounds. Mol Pharmacol. 1975;11:850–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacerdoti D, Gatta A, McGiff JC. Role of cytochrome P450-dependent arachidonic acid metabolites in liver physiology and pathophysiology. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2003;72:51–71. doi: 10.1016/s1098-8823(03)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor M, Schwanekamp J, Halbleib D, Mohamed I, Karyala S, Medvedovic M, Tomlinson CR. Microarray results improve significantly as hybridization approaches equilibrium. Biotechniques. 2004;36:790–796. doi: 10.2144/04365ST02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel SD, Winters GM, Rogers WJ, Ziccardi MH, Li V, Keser B, Denison MS. Activation of the AH receptor signaling pathway by prostaglandins. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2001;15:187–196. doi: 10.1002/jbt.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft AP, Dalton TP, Nebert DW, Genter MB, Puga A, Hutchinson RJ, Kerzee JK, Uno S, Shertzer HG. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen production is dependent on the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]