Abstract

We propose that the NMR solvent signal be utilized as a universal concentration reference because most solvents can be observed by NMR, and solvent concentrations can be readily calculated or determined independently. In particular, a highly protonated solvent such as water can serve as a primary concentration standard for its stability, availability and ease of observation. The potential issues of radiation damping associated with a strong NMR signal can be alleviated by small pulse angle excitations. The solvent signal then can be detected by the NMR receiver with the same efficiency as a dilute analyte. We demonstrated that the analyte's proton concentration can be accurately determined from 4 μM to more than 100 M, referenced by solvent (water) protons of concentrations more than 10 M. The proposed method is robust and indifferent to probe tuning, and does not require any additional concentration standard.

Keywords: NMR, concentration determination, concentration reference

Concentration determination by modern spectroscopic methods typically requires instrument calibration by a standard. While an internal standard is preferred for its advantage of offsetting experimental condition variations, it might be tedious or difficult to make a universal standard for vastly different solutions. Moreover, introduction of an internal standard is subject to some operator uncertainties and may run the risk of causing some physical or chemical changes to the solution. A stable internal standard that is free of these problems and easily available is highly desired.

We propose the solvent be utilized as an internal standard for concentration determination by modern high resolution NMR. Since the FID (free induction decay) in NMR is essentially an emission spectrum, we believe the theoretical linear relationship between the NMR signal amplitude and the concentration can potentially allow any signal to be utilized as a concentration reference. The solvent signal is uniquely suited for this purpose for its ease of observation by NMR and its concentration can be accurately determined or calculated. Tissue water has been suggested as a concentration standard in MRI, although the precision was rather limited and the accuracy could not be independently validated.1, 2 On the other hand, the residual proton signal in a deuterated solvent, once with its concentration determined based on another standard, was demonstrated capable of serving as a internal concentration reference in its solutions.3 We would further argue that essentially any proton containing solvent, regardless how high the proton content is, can indeed serve as a concentration standard. Especially in biological samples, the highly protonated water (frequently with 10% v/v deuteration or less) is a good candidate for consideration as a primary concentration standard.

Significant technical difficulties, such as the potential non-uniform excitation/detection (or RF inhomogeneity), radiation damping for large solvent signals, and non-linear amplification by the NMR receiver due to the dramatic concentration difference between the reference and the analyte, frequently hinder the universal application of any given concentration standard in NMR measurements that require accuracy of 5% or better. However, we realized that the NMR signal size can be easily manipulated by excitation pulse angles. As a result, the receiver gain can be set high and kept the same for both the reference and analyte so that optimum sensitivity for the dilute analyte can be achieved. Furthermore, the RF inhomogeneity information can be obtained from signals of constant or known concentrations. We believe a single solvent concentration standard is sufficient to determine the concentration of almost any analyte that is amenable for observation by NMR, regardless of how concentrated or dilute that analyte is.

In this Note, we demonstrate that the analyte's concentration can be readily determined both precisely and accurately (2% or better) over a wide range (> 6 orders of magnitude) by using dominant water signals (of proton concentration >10 M) as concentration references.

Experimental Section

For simplicity, we focus on protons because they are not only more sensitive but also more frequently observed, although the analysis can be expanded to any other nucleus. Residual solvent protons can always be observed by NMR for any partially or highly deuterated solvent in real life. For an example, even with 99.9% deuteration, a solvent such as chloroform still has a residual proton concentration of more than 10 mM, which can be precisely detected by a modern NMR spectrometer in a matter of minutes and then utilized to as a concentration reference for a dilute analyte dissolved in the same solvent.

In the simplest 1D experiment under normal conditions (free of radiation damping effects), the NMR signal size A (per scan) or the peak integration is proportional to the nucleus' concentration c, the receiver gain function f(RG) and the sine of the pulse excitation angle θ (smaller than or equal to 90°; subscripts s and a represent the solvent and analyte):

| (1) |

To improve spectral quality and sensitivity, data from multiple scans may be summed (and phase-cycled). Then it is required that all reference and interesting magnetizations return to equilibrium, or reach the same steady state before the next scan starts. If the analyte and the reference signals are obtained from different samples, the NMR signal size A will be normalized by its corresponding relative receiving efficiency, which can be correlated to the 90° pulse length.4, 5 Moreover, f(RG) is a function of the receiver gain (RG) describing how much a unit FID signal is amplified by the receiver. If the receiver is linear, then f(RG)=RG.

In accurate concentration determinations, one has to be aware of the RF field inhomogeneity in the NMR samples, if the analyte and the reference have to be observed separately.6 With the excitation angle θ treated as a nominal angle, an inhomogeneity function ℐ(θ) can be introduced to eq.(1):

| (2) |

While a given NMR spectrometer may not have a strict linear receiver, it is convenient to set the receiver gain (RG) to a fixed value for both the analyte and the reference. Then eq.(2) can be simplified to

| (3) |

For modern NMR probes with high RF homogeneity, ℐ is roughly 1, with a weak dependence on θ. If θa and θs are comparable or both are small (less than 15°), ℐ(θa) equals to ℐ(θs). Generally speaking, only the ratio of sin(θ)ℐ(θ) between two excitation angles is important, and that value can be determined accurately from any reference of constant concentration. Again, the residual solvent signal offers such a reference.

Radiation damping may be significant for the strong solvent signal. As a result, its line-shape, phase and peak integration may be distorted.7 Nevertheless, it is possible to mitigate the detrimental impacts on the phase or peak integration by employing a small excitation angle or using a less protonated solvent (i.e.2% H2O).8 Under such conditions, eq.(3) continues to hold for the strong solvent signal.

NMR Samples partially deuterated samples were made by diluting a stock D2O (>99% deuteration) by distilled water, and their respective amount was measured by weight (table 1). The exact proton content in each sample could be calculated, once that of the stock D2O stock was determined (as 0.536% v/v; vide infra).

Table 1.

A set of partially deuterated water samples were made by adding stock D2O (>99% v/v deuteration) to water, with individual components weighed. Proton content for each sample could be calculated after the exact residual proton amount in the stock D2O was accurately determined (see RESULTS AND DISCUSSION section).

| D2O samples | H2O weight (mg) | D2O (>99 v/v) weight (mg) | τ90 (μs) | Calculated H2O content (v/v %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock D2O | 0 | - | 8.64 | 0.537a |

| 1 | 33 | 634.1 | 8.64 | 5.96 |

| 2 | 181.3 | 469.4 | 8.67 | 30.3 |

| 3 | 362.3 | 270.3 | 8.72 | 60.0 |

| 4 | 570.7 | 36.0 | 8.77 | 94.6b |

residual proton content was determined, using sample 4 as a reference (proton content 94.6% v/v)

calculated residual proton content varies less than 0.1%, if residual proton content in the stock D2O varies between 99% and 100%.

168 mg sodium acetate (specific assay 100.1%) was dissolved in 45.28g water at room temperature, resulting in the acetate concentration as 39.6 mM. Subsequently 1 ml stock D2O (99.5% v/v deuteration) was added to 10 ml above solution, leading to a stock solution containing 36.0 mM sodium acetate and 9.05% D2O (v/v). 200 μl of the stock solution was further diluted by 800 μl 2 M NaCl solution and water to make a set of 7.20 mM sodium acetate samples with NaCl concentration up to 1.6 M (table 2).

Table 2.

A set of constant concentration (7.20 mM) sodium acetate solutions were made by adding 200 μl 36.0 mM sodium acetate 9.05% D2O solution to 800 μl 2 M NaCl and water. The total volume of each solution was assumed to be the simple sum of individual volumes. The resulting NaCl concentrations in this set of samples ranged from 0 M or 1.6 M, and D2O content was 1.81% (v/v) throughout.

| 36.0 mM NaOAc stock solution (ml) | 2 M NaCl in water (ml) | H2O (ul) | final NaCl concentration (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 0 | 800 | 0 |

| 200 | 25 | 775 | 0.05 |

| 200 | 50 | 750 | 0.1 |

| 200 | 75 | 725 | 0.15 |

| 200 | 100 | 700 | 0.2 |

| 200 | 125 | 675 | 0.25 |

| 200 | 150 | 650 | 0.3 |

| 200 | 200 | 600 | 0.4 |

| 200 | 300 | 500 | 0.6 |

| 200 | 400 | 400 | 0.8 |

| 200 | 600 | 200 | 1.2 |

| 200 | 800 | 0 | 1.6 |

Distilled water was added to 92.7 mg N, N-dimethylformide (DMF; 99.8% purity) to a final weight of 17.478 g, resulting in a 72.4 mM DMF solution. A 256 μM DMF solution was made by diluting 52.3 mg of the above solution with water to a final weight of 14.783 g. 20 μl D2O of the stock D2O was added to 480 μl 256 μM DMF, leading to the DMF concentration of 246 uM and water proton concentration of 106.4 M (or 96.0% v/v).

62.7 mg 256 μM DMF solution was added to 588 mg stock D2O resulting in DMF concentration of 26.9 μM and water proton concentration of 12.2 M (or 11.0% v/v).

NMR spectroscopy All NMR data were acquired on a Bruker Avance 800 spectrometer operating at 25°C with the probe tuned and matched to 50 Ω. Acquisition time was 4 s and sweep width was 10 ppm. Delays between successive data acquisitions were generally set sufficiently long so that all magnetizations could essentially return to equilibrium (e.g. 40 s for DMF and 60 s for acetate if the excitation pulse angle is 90°). Receiver gain was fixed for any given sample or set of samples that share the same concentration reference, to overcome the receiver's potential non-linearity. The water signal was observed using small excitation angles so that the peak integrations were not compromised by radiation damping. In particular, to observe dilute analytes (246 μM and 26.9 μM DMF), the receiver gain was set to 80.6 after WET water suppression, which accommodates good sensitivity and still avoids receiver saturation. The water proton signal was observed in a separate acquisition with a very small-angle excitation pulse.

All FID's were exponentially broadened by 0.1Hz, Fourier transformed and phased manually, followed by polynomial baseline corrections. NMR signal sizes were treated as simple sums of corresponding peak intensities over the range of about 50 times the natural line-width at full height.

Results and Discussion

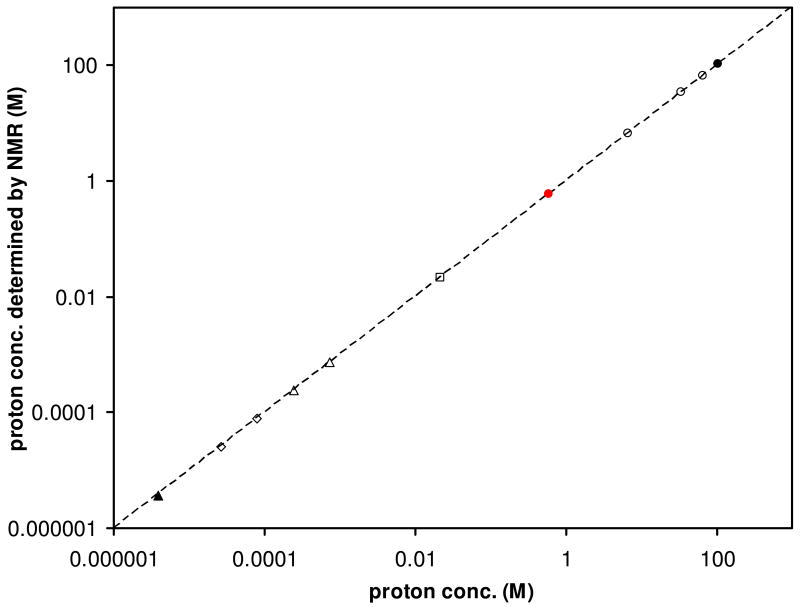

Fig 1 demonstrates the correlation between the expected and NMR determined proton concentrations (open circles, square, diamonds, triangles), using the solvent protons (> 10 M) as the concentration references. The ideal correlation is plotted as the dashed line with a slope of 1. For proton concentrations above 75 μM, the experimentally determined values are within 2% of the expected. For proton concentrations of 26.9 μM and 4.0 μM, the experimental values are 4.5 and 8% underdetermined, presumably due to the lower signal-to-noise ratios achieved within a limited amount of time.

Figure 1.

Experimental proton concentrations, determined by NMR signal sizes at room temperature, for partially deuterated water (open circles), sodium acetate (square) and DMF (diamonds, triangles) are plotted against the expected values. The dashed line shows the ideal correlation between experimental and expected values with a slope of 1. Standard deviations are generally too small to be plotted for concentrations higher than 75 μM.

The circles in Fig 1 represent the stock D2O (>99% deuteration) and four dilutions of the stock D2O in H2O (table 1). First, the most protonated water sample's proton content can be assumed to be 94.6% v/v (or 104.9 M) at room temperature (filled black circle), because majorities of its protons come from the protonated water: this sample's proton concentration is expected to vary less than 0.1% even if the D2O stock's deuterium content varies between 99% and 100%. By comparing their normalized NMR signal sizes with that of the 104.9 M sample, the residual proton concentrations in other three less protonated water samples (open circles) and the stock D2O (filled red circle) were determined to be 66.4 M, 33.6 M, 6.60 M and 0.594 M, each with standard deviation less than 0.1%. With the knowledge of proton content in the stock D2O (0.594 M or 0.537% v/v) and how each solution was made (table 1), one could easily calculate the three aqueous samples' proton concentrations as 66.8 M, 33.8 M and 6.66 M (open circles). Hence the NMR determined proton concentrations are all within 1% of the expected values. As all five samples were loaded into different NMR tubes, the NMR signal sizes had to be normalized by the receiving efficiency or 90° pulse length.4, 5 Essentially, this can be the strategy to determine any solvent proton concentration for any given sample including any deuterated solvent on the fly using an external protonated solvent reference.

The two open triangles in Fig. 1 represent the formyl and methyl proton (per methyl) concentrations from an aqueous sample containing 246 μM dimethylformide (DMF) and 4.0% (v/v) D2O. Considering the fact that the proton concentration in the aqueous sample is very high (calculated as 106.4 M at room temperature) and will likely create a much stronger signal than those from the DMF protons, we decided to acquire two proton spectra separately to achieve good sensitivity for the dilute analyte: DMF was first observed with a angle pulse (θs) about 11.25° and a receiver gain of 80.6, after a WET water suppression;9 then the water proton was detected after another very small angle pulse excitation (θs ∼ 0.715°) so that the same receiver gain could be applied without causing signal saturation. The exact pulse angles are not so critical, since the value of sin(θa)ℐ(θa)/sin(θs)ℐ(θs) in eq.(3) was experimentally determined as the signal size ratio by applying the those two excitation angles to the same resonance. Again, the solvent signal (or any other clear strong signal) can readily serve for this purpose and sin(θa)ℐ(θa)/sin(θs)ℐ(θs) was found to be 15.4 in the current case. Alternatively, sin(θa)/sin(θs) in eq.(3) can be calculated as 15.6 from the assumption of the transmitter's linear power attenuation, and the ratio of the RF inhomogeneity factor ℐ(θa)/ℐ(θs) can be treated as 1. With a modest number of scans, the concentration was determined to be 242 ± 3 μM for the DMF formyl proton and 748 ± 6 μM for the methyl protons (per methyl; corrected for the exclusion of natural abundance 13C satellites in peak integrations), both of which are accurate within 2% of the expected 246 μM and 738 μM.

Furthermore, we examined the methyl satellite peaks of DMF in this sample arising from the 1.07% natural abundance 13C.10 The solvent proton signal was observed with the same small angle excitation pulse (θs ∼ 0.715°), and the solute FID was acquired after water suppression and a nominal 90° excitation pulse. The experimental methyl proton concentration (per satellite) was determined as 3.63 ± 0.1 μM (filled triangle in Fig 1), while the expected is 3.95 μM. The error is 8%.

The two open diamonds in Fig 1 are concentrations of the formyl and methyl protons (per methyl) in the aqueous sample containing 26.9 μM DMF. The solvent water proton was calculated as 11.0% (or 12.2 M), based on the information of the proton content in the stock D2O (filled red circle) and its dilution by H2O. The same strategy of two different excitation angles (90° for DMF and 2.85° for water) was employed and the value of sin(θa)ℐ(θa)/sin(θs)ℐ(θs) was experimentally determined as 20.9 using the water resonance (or 20.4 by calculation, assuming ℐ(θa)/ℐ(θs) is still 1). With the solvent proton as the concentration reference, the DMF proton concentration was found to be 25.7 ± 0.4 μM for the formyl and 79.7 ± 0.6 μM for each methyl group. Compared with the expected 26.9 μM and 80.7 μM, the experimental values are 4.5% and 1.2% under-determined. Since some of the proton signals might be reduced in baseline corrections, it is not unexpected that the very dilute DMF protons (<75 μM) tend to be under-determined by eq.(3). Under same conditions, the formyl proton is more prone to underestimation due to its broader apparent line-width however longer spin-lattice relaxation time.

Finally, the open square in Fig 1 is the average proton concentration from twelve 7.20 mM sodium acetate aqueous samples, in the presence of up to 1.6 M sodium chloride (table 2). In this series of samples, the acetate proton and water proton signals could readily be observed simultaneously with a moderate receiver gain after a small angle pulse excitation. Therefore, the angular terms in eq.(1) or (3) would disappear. The water proton concentration was calculated from the known solution density of each sample (ignoring the impact of the relatively small amount of sodium acetate),11 and then reduced by 1.81% to reflect the small amount of D2O added to all samples (solid line in Fig 2). The signal size for acetate was obtained by peak integration excluding the 1.07% 13C natural abundance satellites, and then corrected by 0.989. The averaged molar concentration of acetate for twelve samples (squares in Fig 2), taken as one-third of the methyl proton concentration, was determined to be 7.23 ± 0.14 mM, which again differs from the expected value of 7.20 mM (Fig 2 dashed line) by less than 1%.

Figure 2.

Sodium acetate concentrations (open squares) were determined using solvent water (98.2% proton) as the internal concentration reference. The average concentration determined by NMR is 7.23 +/- 0.14 mM, while the expected value is 7.20 mM for all samples (dashed line). Presence of sodium chloride (up to 1.6 M) may cause several percent drop in water proton concentration. However, that has a minimal impact to the concentration determination, since water proton concentration (solid line) can still be accurately calculated from known densities.

In the current study, we have used DMF, acetate and residual solvent protons in aqueous solutions as examples to show the good linear relationship between NMR determined and expected proton concentrations over a wide concentration range. In practice, eqs.(1) and (3) can be easily extended to determine any proton's concentration. Hence, the knowledge of the solvent proton concentration as the concentration reference is critical. In most dilute aqueous biological samples, the solvent is frequently dominated by water, the concentration of which can be readily calculated from their densities, even in the presence of some common salts such as sodium chloride or sodium phosphate.11 If the proton concentration is high (>1 M), the solvent should be observed by a small angle pulse to alleviate radiation damping effects and avoid receiver saturation. The analyte's signal can be observed separately by a different excitation pulse for optimum sensitivity after the solvent suppression.

In some dilute aqueous or organic samples with a highly deuterated solvent, the residual solvent and the analyte proton signals can be conveniently observed by the same excitation pulse. In that case, the concentration ratio is reduced to the NMR signal size ratio according to eq.(1) and the RF inhomogeneity factor in eq.(3) would cancel. While most deuterated solvents have their deuterium content specified by the vendors, the residual proton concentration calculated from that information is frequently inadequate to be utilized as an accurate concentration standard without further calibration.3 Additionally, the amount of residual solvent proton can vary depending on the storage condition or usage history: for example, DMSO or deuterium oxide may absorb moisture (protonated water) in the air. Nevertheless, NMR again can offer a straightforward way for residual proton content determination once and for all or on a regular basis, by comparing the signal size with that of a known external reference such as a highly protonated water reference (vide supra). As the circles in Fig 1 show, such a strategy works rather well, with accuracy of 1% or better. Once the proton content is accurately known, a partially deuterated solvent is ready to be used as an internal reference for any dilute sample that it makes.

On the other hand, not all solutions are known priori to be dilute or behave ideally. Moreover, the solute may increase or decrease the residual proton content of the solvent, even though the solution is still dilute. In general, the residual proton concentration can be determined by NMR using another solvent (e.g. a highly protonated water) as either an internal or external concentration reference. For an example, a deuterated DMSO solvent's residual proton concentration can be readily determined by adding water to it. Alternatively, the residual proton concentration can be referenced by a separate water sample. In the external reference method, the receiving efficiency or 90° pulse length frequently differ between the interesting sample and the reference, and hence the signal sizes in eqs.(1) and (3) need to be corrected.4, 5 Once the residual proton concentration of the solvent becomes known, it can be used for further calculations if the solution will be subsequently diluted, or serve as an internal concentration standard in the same solution next time when the probe tuning condition may change and/or data are acquired on an different NMR spectrometer.

Throughout the current study, we have chosen the water proton signal as the concentration reference. Potentially the strategy can be applied to other nuclei. The solvent signal is at its best when used as an internal concentration reference so that sample volume or the RF inhomogeneity does not influence the outcome. Of course, any known proton signal can be utilized as a standard. For an example, trimethylsilyl-2,2,3,3-tetradeuteropropionate (TSP) or any other randomly chosen compound can serve as a concentration standard (the role of TSP as the chemical shift reference is ignored here). However, such an internal concentration reference may come at some cost and risk: for a large number of samples, significant amount of the reference compound might be consumed, and manual or automatic accurate introduction of the reference to every sample may need independent validation; second, addition of the concentration reference to an interesting sample not only dilutes that sample but may also suffer from interactions with proteins in biological samples;12 third, hygroscopicity, limited purity, long term stability or solvent volatility may prevent TSP or another randomly chosen reference as a good choice to serve as a primary concentration standard.

While the residual solvent signal, once calibrated by another primary concentration reference, can serve as an internal concentration, one has to make sure that the solute or any salvation process does not significantly change the proton content of the solvent. For an example, a hygroscopic compound may render the residual proton content of a D2O solution no longer reliable even though the proton content has been pre-determined. Here we would argue that a protonated solvent can serve as a primary concentration standard to determine the residual proton content in the deuterated solvent stock. In particular, neat water (with optional minimal deuteration for spectrometer locking) is an excellent choice as the primary proton NMR concentration standard for its many virtues including no cost, no hazard, simplicity, high stability, ready availability and well characterized properties under normal conditions.

More recently, we proposed the concept of receiving efficiency, which is a quantitative measure of how efficient the NMR signal can be observed from a unit excited magnetization.4 While nuclei of the same type in the same sample generally have the same receiving efficiency regardless of chemical shift difference, the NMR signal size needs to be normalized by the receiving efficiency in case of external referencing. Concentration can be accurately determined by an external reference such as neat water. However, this method does require good NMR practice, and may not work very well when the NMR sample volume is less than the active volume that a probe coil allows (e.g. when the sample is placed into a restrictive Shigemi tube).

An artificial signal termed ERETIC was suggested to serve as the concentration reference.13 This method is essentially using an external reference, because the ERETIC signal itself has no physical meaning and has to be calibrated separately by a real standard. Neither is it influenced by the excitation angle or RF inhomogeneity. Generating such a signal frequently requires re-arranging spectrometer cables and/or filters. Moreover, the ERETIC signal can become easily misused if constant sample load and consistent probe tuning cannot be maintained for both the observed nucleus (proton) and the ERETIC channel.

The advantages of using solvent signal as the concentration reference especially as an internal reference include easy preparation, as the solvent concentration is only dependent on solution density (for a dilute sample) and generally indifferent to its volume. Moreover, acquiring a separate spectrum for the solvent signal after a small angle excitation, if needed, is quite straightforward, since the solvent's proton content is likely to be reasonably high (sub-molar range or higher) and predictable based on the known densities or common sense. The effort in maintaining a certain reference concentration itself can be greatly reduced even if that concentration may still need to be determined or calibrated. Furthermore, the internal solvent concentration reference has no special requirements for operating temperature or probe tuning conditions.

The errors in the current concentration determination study mainly come from several sources. First, the peak integration can have about 1% error, due to the combination of limited integration range and signal to noise ratio. In the example of 3.95 μM DMF proton concentration determination, the signal-to-noise ratio is about 10, and the baseline tends to be overcorrected leading to under-integration. In such a case, curve-fitting may produce more accurate results than the simple sum of peak intensities.14 Second, the reference concentration or expected concentration is subject to some uncertainties arising from either the assumption of dilute solutions or the way each solution was made. As a result, using a highly protonated solvent such as water is beneficial. Third, WET water suppression sequence can attenuate the observed analyte signals, depending on the offset and selective RF pulse strength. In the current study, the estimated impact is about 0.5%. Finally, excitation angle determination in separate data acquisitions can potentially introduce up to 1% error too. In our experience, the error in concentration determinations can be controlled within 2% under favorable conditions if the signal-to-noise ratio is sufficient and interesting peaks are reasonably resolved (free of severe spectral overlaps).

Conclusions

The solvent concentration referencing method is robust, and eliminates the need to prepare any additional internal, external or artificial standard. With demonstrated precision and accuracy of 2% or better from 100 M to 75 μM (or lower) and the ability to detect almost all organic and many inorganic compounds, NMR offers an essentially universal concentration determination method.

Supplementary Material

Table lists of water and DMF concentrations for Fig 1, and acetate concentrations for Fig 2.

Acknowledgments

Partial support to D.R. from the National Institutes of Health (1R01GM085291-01) and assistance in sample preparation by Dr. Zhenglai Fang are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Gasparovic C, Song T, Devier D, Bockhol HJ, Caprihan A, Mullins PG, Posse S, Jung RE, Morrison LA. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1219–1226. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreis R, Ernst T, Ross BD. J Magn Reson B. 1993;102:9–19. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierens GK, Carroll AR, Davis RA, Palframan ME, Quinn RJ. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:810–813. doi: 10.1021/np8000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mo, H; Zhang, S; Harwood, J. S.; Xue, Y.; Santini, R.; Raftery, D. unpublished work, Purdue University, West Lafayette, 2008

- 5.Wider G, Dreier L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2571–2576. doi: 10.1021/ja055336t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szantay C., Jr J Magn Reson. 1998;135:334–352. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao XA, Guo JX. Phys Rev B. 1994;49:15702–15711. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.49.15702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connell MA, Davis AL, Kenwright AM, Morris GA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:1568–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogg RJ, Kingsley PB, Taylor JS. J Magn Reson B. 1994;104:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden NE. In: CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. 82nd. Lide DR, editor. CRC press; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. section 11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lide DR. In: CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. 82nd. Lide DR, editor. CRC press; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. section 8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu A, Ikeguchi M, Sugai SJ. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:859–862. doi: 10.1007/BF00398414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akoka S, Barantin L, Trierweiler M. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2554–2557. doi: 10.1021/ac981422i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rischel C. J Magn Reson A. 1995;116:255–258. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table lists of water and DMF concentrations for Fig 1, and acetate concentrations for Fig 2.