Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are common causes of ineffective hematopoiesis and cytopenias in the elderly. Various myelosuppressive and proinflammatory cytokines have been implicated in the high rates of apoptosis and hematopoietic suppression seen in MDS. We have previously shown that p38 MAPK is overactivated in MDS hematopoietic progenitors, which led to current clinical studies of the selective p38α inhibitor, SCIO-469, in this disease. We now demonstrate that the myelosuppressive cytokines TNFα and IL-1β are secreted by bone marrow (BM) cells in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. Their secretion is stimulated by paracrine interactions between BM stromal and mononuclear cells and cytokine induction correlates with CD34+ stem cell apoptosis in an inflammation-simulated in vitro bone marrow microenvironment. Treatment with SCIO-469 inhibits TNF secretion in primary MDS bone marrow cells and protects cytogenetically normal progenitors from apoptosis ex vivo. Furthermore, p38 inhibition diminishes the expression of TNFα- or IL-1β-induced proinflammatory chemokines in BM stromal cells. These data indicate that p38 inhibition has anti-inflammatory effects on the bone marrow microenvironment that complements its cytoprotective effect on progenitor survival. These findings support clinical investigation of p38α as a potential therapeutic target in MDS and other related diseases characterized by inflammatory bone marrow failure.

Introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) comprise a hematologically and biologically diverse group of stem cell malignancies characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis that leads to refractory cytopenias with increased risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [1,2]. MDS is characterized by a clonal expansion of abnormal hematopoietic stem cells within a bone marrow (BM) microenvironment with aberrant homeostasis associated with increased extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and excess production of inflammatory cytokines [1-3]. Cytokines play an important role in the regulation of hematopoiesis and a fine balance between the actions of stimulatory hematopoietic growth factors and myelosuppressive factors is required for optimal production of cells of different hematopoietic lineages. Since functional hematopoietic failure is the cause of cytopenias in MDS, cytokine dysregulation has been targeted as one contributory mechanism potentially amenable to therapeutic intervention [3].

The overproduction of varied proinflammatory cytokines has been implicated in the pathobiology of MDS. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) is a classic pro-apoptotic cytokine that is known to promote progenitor apoptosis in MDS [4,5]. High plasma concentrations of TNFα have been observed in the peripheral blood [6] and bone marrow [7] of MDS patients, and a higher expression of TNF receptors and TNF mRNA have also been reported in MDS bone marrow mononuclear cells [8,9]. Interferon γ (IFNγ) has been implicated strongly in aplastic anemia [10-12] and the hematopoietic failure of Fanconi anemia [13], and in certain MDS subtypes, bone marrow mononuclear cells display increased levels of IFNγ mRNA transcripts compared to healthy controls [14]. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) is an angiogenic cytokine implicated in the generation of inflammatory cytokines through its paracrine effects [15]. VEGF also dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo [16] and has been shown to support the self-renewal of cytogenetically abnormal clones in the bone marrow [15]. Myelomonocytic precursors in MDS display increased cellular VEGF and higher expression of high affinity VEGFR-1 receptor, implicating an autocrine stimulatory loop [17]. Similarly, increased production of IL-1β are demonstrable in MDS bone marrow mononuclear cells [8], whereas the spontaneous production of IL-1β in AML blast cells has been implicated in the pathogenesis of leukemia transformation [18,19]. IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that has variable regulatory effects on hematopoiesis [20]. At physiological concentrations, IL-1β acts as a hematopoietic growth factor that induces other colony stimulating factors (CSF), such as granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) and IL-3 [21]. At higher concentrations, as in chronic inflammatory bone marrow states, IL-1β leads to the suppression of hematopoiesis through the induction of TNFα and PGE2, a potent suppressor of myeloid stem cell proliferation [20]. In addition to these cytokines, high levels of Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) are also demonstrable [17]. Collectively, these data indicate that many different cytokines may have pathogenetic roles in the ineffective hematopoiesis of MDS regulated through paracrine and autocrine interactions.

MDS bone marrow stromal cells and infiltrating mononuclear cells have been implicated in the production of pathogenetic cytokines. Stromal cells are an important source of cytokine production and play a role in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma, myelofibrosis, and many other hematologic diseases [22-24]. It remains unclear whether stromal cells in MDS are intrinsically defective [25-28] or are simply reactive bystanders [7,29,30]. The bone marrow microenvironment includes macrophages and lymphocytes that are potent producers of TNFα and IFNγ, cytokines implicated in the increased apoptosis seen in aplastic anemia, a bone marrow failure disease with phenotypic overlap with MDS [8,31]. Lymphocyte populations are commonly clonally expanded in MDS, supporting the notion that host immune cells may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease in select individuals [32-35]. In fact, recent findings have shown that clonally expanded CD8+ lymphocytes in MDS cases with trisomy of chromosome 8 display specificity for WT-1, a protein encoded on this chromosome and overexpressed in this MDS subtype [34,35]. These clonal lymphocyte populations directly suppress hematopoiesis by progenitors containing the trisomy 8 abnormality, providing evidence for involvement of immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ineffective hematopoiesis [34,35]. Even though studies suggest that both stromal cells and infiltrating immune effectors may interact with the MDS clone to create an adverse cytokine milieu fostering ineffective hematopoiesis, the molecular mechanisms involved in cytokine generation are not known. Signaling pathways involved in the generation of proinflammatory cytokines in MDS would be attractive targets for therapeutic intervention with perhaps greater disease specificity.

One important regulatory pathway is the p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway. The p38 MAPK is a serine/threonine kinase, originally discovered as a stress-activated kinase that is involved in transducing inflammatory cytokine signals and in controlling cell growth and differentiation [36-38]. Our recent data have shown that p38 MAPK is activated in lower risk MDS bone marrows and that increased p38 activation correlates with increased apoptosis of normal progenitors [39]. Pharmocological inhibition of p38 kinase activity or downregulation of p38 expression by siRNAs leads to stimulation of hematopoiesis in MDS progenitors. Additionally, we have shown that treatment with SCIO-469, a potent and selective inhibitor of p38α, increases erythroid and myeloid colony formation from MDS hematopoietic progenitors in a dose-dependent fashion [39]. Constitutive activation of p38 MAPK in MDS bone marrow could arise from chronic stimulation by proinflammatory cytokines present in the MDS microenvironment. In this report, we show that elaboration of many of these cytokines from bone marrow cells is regulated by p38α. Inhibition of p38α activity by SCIO-469 not only leads to the reduction in the production of these cytokines, but also to the inhibition of their effects on the secondary induction of other proinflammatory factors that may contribute to the pathobiology disease.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human IL-1β, TNFα, IL-12, IL-18, stem cell factor (SCF), thrombopoietin (Tpo), Flt3-ligand (FL) and TGF-β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies CD45-FITC, CD34-PerCP, CD3-Pacific Blue, CD19-APCCy7, CD56-PECy7, CD14-APC, IL-1β-PE, TNFα-PE, phospho-p38-PE, and their corresponding fluorochrome-conjugated isotype IgG control antibodies were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Brefeldin A (Golgi Plug) was obtained from BD Biosciences.

The p38α MAPK inhibitor SCIO-469 was synthesized by Medicinal Chemistry (Scios Inc.; Mountain View, CA). SCIO-469 has an IC50 of 9 nM for inhibition of p38α based on direct enzymatic assays, about 10-fold selectivity for p38α over p38β, and at least 2000-fold selectivity for p38α over a panel of 20 other kinases, including other MAPKs. No significant affinity was detected in a panel of 70 enzymes and receptors. In a cell based assay for inhibition of LPS-induced TNFα secretion in whole human blood, an IC50 of 1.3 μM is observed.[39]

BMMNC and BMSC Cell Cultures

Primary human bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNC) were obtained from MDS patients after IRB-approved informed consent from the institutional review boards of Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the University of South Florida. BMMNC were isolated by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation. Whole blood was diluted 1:1 with Iscove's Modified Dulbecco Medium (IMDM, Cambrex; Walkersville, MD) containing 2% FBS and 10 mL of diluted sample was layered onto 15 mL Ficoll-Paque (Stem Cell Technologies; Vancouver, B.C., Canada) in a 50 mL conical tube at room temperature. The tube was centrifuged at 400 g for 30 min. The top plasma layer was discarded while the whitish mononuclear layer was transferred to a 17 × 100 mm polystyrene tube. Cells were washed with 10 mL of IMDM + 2% FBS twice and resuspended in 1 mL IMDM + 2% FBS. Normal BMMNC were obtained cryopreserved from Cambrex (Atlanta, GA) and maintained in IMDM + 15% FBS containing 50 ng/mL each of SCF, Tpo, and FL.

Non-irradiated bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) from normal donors were obtained from Cambrex and maintained in Myelocult H5100 medium supplemented with 10−6 M hydrocortisone (Stem Cell Technologies). BMSC from MDS patients were derived from adherent layers that grew after two weeks in cell cultures of MDS BMMNC in IMDM + 10% FBS containing the hematopoietic stem cell cytokine panel. These cells were subsequently maintained in Myelocult H5100 medium.

Bone marrow sera from 3 MDS patients (after IRB approved informed consent) were obtained after centrifugation of bone marrow aspirates. 100uL of these were added to 2.4ml of methylcellulose containing cytokines and 10,000 normal bone marrow derived CD34+ cells. This was plated in duplicate and BFU-Erythroid and CFU-GM colonies were counted after 14 days of culture as described before [40]

ELISA

Concentration of TNFα in cell culture supernatants was assayed using ELISA kits from BioSource International (Camarillo, CA).

Multicolor Flow Cytometry

BMMNC were washed in FBS buffer (PBS containing 1% FBS and 0.09% sodium azide, BD Biosciences) and then stained with fluorochrome-conjugated receptor antibodies for 30 min at RT. Cells were washed twice in FBS buffer and then simultaneously fixed and permeabilized in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed twice in 1X staining solution (Cytoperm/Cytowash, BD Biosciences) and intracellularly stained with either TNFα-PE or IL-1β-PE for 30 min at RT. Cells were washed twice in staining solution and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS. Cells were analyzed by multicolor flow analysis using the BD LSR II flow cytometer and the FACSDiva software program (BD Biosciences).

Apoptosis Assay

Detection of apoptotic cells was performed by staining with Annexin V-PE and 7-Amino Actinomycin D (7-AAD) (BD Pharmingen; San Diego, CA). BMMNC samples were co-stained with anti-CD34-PE Cy7 and CD45-APC Cy7 to detect apoptosis of CD34+ progenitors (CD34+CD45− cell population). Samples were analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry using the BD LSR II flow cytometer and the FACSDiva software program. 7-AAD is a nucleic acid dye that is used to exclude nonviable cells in flow cytometric assays. Cells that were Annexin V-PE positive and 7-AAD negative were considered early apoptotic.

Intracellular cytokine staining

To enumerate TNF production by MDS bone marrow mononuclear cells, intracellular cytokine staining was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions [41]. Briefly, isolated BMMNC were incubated in the presence of 10 μg/mL of immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (145-2C11, ATCC; Manassas, VA) plus 2 μg/mL of anti-CD28 antibody (PV-1, ATCC) in the presence of monensin for 6 h at 37°C. Addition of anti-CD28 antibody providing costimulation and monensin blocking secretion of the cytokines during the incubation allows sensitive assessment of cytokine producing cells. After the stimulation, the cells were stained with CD14-PE antibody. The cells were then fixed, permeabilized and stained for intracellular TNF using APC-labeled antibody according to the protocol of BD Biosciences.

cDNA Microarray Analysis

Details of microarray and data analysis have been described previously[42] The data was normalized using the maNorm function in marray package of Bioconductor version 1.5.8. Differential expression values were expressed as the ratio of the median of background-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the experimental RNA to the median of background-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the control RNA. The total BMSC RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA). Arrays were probed in quadruplicate for a total of 16 hybridizations: control versus TNF□ (24 hours), TNFα̣ versus SCIO-469 + TNFα (24 hours), control versus IL-1β (24 hours), IL-1β versus SCIO-469 + IL-1β (24 hours).

Fluorescent In situ hybridization

Primary MDS bone marrow aspirate cells were treated in the presence and absence of SCIO-469 (500uM) for 48 hours and then cytospun on slides. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (FISH) was performed on methanol-acetic acid fixed interphase nuclei using the manufacturer's protocol (Vysis, IL. USA) with slight modifications. Slides were denatured in 70% formamide/2X SSC at 72°C for 5 minutes and dehydrated in a cold ethanol series. Probes against EGR1 on chromosome 5q31 locus and centromeric controls (D5S23, D5S721, Vysis, IL) were used to detect cells with chromosome 5q deletion. Probes were mixed with appropriate volumes of buffer/distilled water and denatured at 72° C for 5 minutes. Probe mixtures were applied to denatured chromosomes and placed in a moist chamber at 37° C overnight. Post-hybridization washes for all the probes were in a 0.4X SSC/0.3% NP-40 solution at 73° C for 2 minutes, and then in 2X SSC/0.1% NP-40 solution at room temperature. Air-dried slides were then counterstained with DAPI. FISH images were captured (Zeiss Axioplan II Imaging, Germany), enhanced and stored using the computerized image analysis system (Metasystems, MA. USA).

Results

1. Inflammatory bone marrow mononuclear cells secrete TNFα and IL-1β in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner

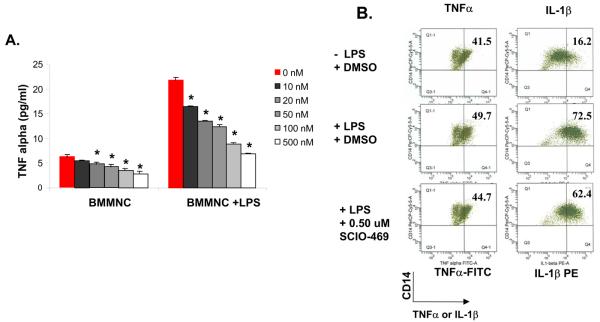

We have previously shown that p38 MAPK is highly activated in a majority of BM cells from MDS patients [39]. This activation was noted in stromal cells, infiltrating mononuclear cells as well as hematopoietic progenitors [39]. As TNFα and IL1-β are proinflammatory cytokines that are found to be overexpressed in MDS patients [3], we wanted to determine the role of p38 MAPK in the generation of these cytokines in the bone marrow. Since the specific inducer of proinflammatory cytokine expression in MDS is still largely unknown, we initially used LPS as a primary inducer of inflammation in primary human bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNC). Both basal and LPS-induced TNFα production was detected by ELISA from supernatants of normal BMMNC cultures after 24 hours (Fig. 1A). Treatment with the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SCIO-469, currently being used in clinical trials in MDS, potently inhibited the secretion of TNFα from both basal or LPS-induced cell cultures with an IC50 of 50 nM (Fig. 1A). IL-1β is another proinflammatory cytokine implicated in MDS pathogenesis. LPS is known to highly induce both TNFα and IL-1β expression in peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes even after only 3 hours of in vivo or in vitro stimulation (37). Thus, we compared the LPS-induced expression of both TNFα and IL-1β in adherent CD14+ monocyte/macrophage cells isolated from the BM of a different normal donor (Fig. 1B). Intracellular flow cytometry revealed that IL-1β was induced earlier (after 4 hours of LPS stimulation) when compared to TNFα in BM-derived CD14+ cells and was dose-dependently inhibited by SCIO-469 (Fig 1C,D). Further analysis showed (Fig. 1C) that IL-1β expression was induced in BM CD14+ monocytes as well as in CD34+ progenitor cells but not in BM-derived CD56+ NK cells, CD3+ T cells or CD19+ B cells. SCIO-469 effectively reduced the intracellular IL-1β expression in both CD14+ and CD34+ populations (Fig. 1C). While TNFα may not have been highly induced early in BM CD14+ cells (after 4 hours of LPS stimulation) we wanted to determine if IL-1β, which is induced and secreted early under these conditions, could have re-stimulated the same BM cells to secrete TNFα at the later time point. IL-1β stimulated TNFα expression specifically in BM CD14+ monocytes and CD3+ T cells after 24 hours (Fig. 1D). TNFα expression in these cells as well as in CD56+ NK and CD19+ B cells was inhibited by SCIO-469 in a dose-dependent manner, with TNFα inhibition reaching below basal levels in different cell types (Fig 1E). Thus p38 MAPK activation was required in the generation of both IL-1β and TNFα from primary bone marrow cells.

Figure 1. Inflammatory bone marrow mononuclear cells secrete TNFα and IL-1β in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner.

A. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNC) (1 × 106) from a normal healthy donor were cultured in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of SCIO-469 for 24h without or with 10 ng/mL LPS. TNFα concentration in cell supernatants was determined by ELISA. Figure represents Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 vs “DMSO”. B. Primary BM-derived CD14+ cells from a normal donor were incubated in IMDM + 10% FBS in the presence or absence of 20 ng/mL LPS and SCIO-469 for 4h. Brefeldin A (golgi plug) was added to a final concentration of 2 ug/mL during the last hour of incubation. Cells were harvested, washed with FBS staining buffer and labeled with anti-CD14-PerCP Cy5.5 followed by intracellular staining with anti-IL-1β–PE and anti-TNFα–FITC. Figure shows percent double-stained CD14+ TNFα+ (left) and CD14+ IL-1β+ (right) in the same cell population. C. BMMNC from a normal donor (1 × 106) were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL LPS for 4h. Brefeldin A (golgi plug) was added to a final concentration of 2 ug/mL during the last hour of incubation. Cells were harvested, washed and labeled with different fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD14 (monocytes), CD56 (NK cells) and CD34 (progenitor cells) followed by intracellular staining with PE-conjugated anti-IL-1β. Figure shows the relative IL-1β expression for each of the specific BM populations: CD14+ cells (green), CD34+ cells (light blue), CD56+ cells (violet). D BMMNC from a different normal donor (1 × 106) were treated with or without 0.5 μM SCIO-469 and incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL LPS for 4h. Brefeldin A (golgi plug) was added to a final concentration of 2 ug/mL during the last hour of incubation. Cells were harvested, washed and labeled with different fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD45 (leukocytes), CD14, CD3 (T cells), CD19 (B cells), CD56 and CD34 followed by intracellular staining with PE-conjugated anti-IL-1β. Figure shows the relative IL-1β expression for each of the specific BM population. Results are expressed as Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.001 or *P < 0.01 vs “+ LPS − SCIO-469”. E. BMMNC (1 × 106) were incubated without or with increasing concentrations of SCIO-469 and in the presence or absence of 50 ng/mL IL-1β for 24h. Brefeldin A was added to a final concentration of 2 ug/ml during the last 2 hours of incubation. Cells were harvested, washed, labeled and then fixed with different fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD45, (leukocytes), CD14 (monocytes), CD3 (T cells), CD19 (B cells), CD56 (NK cells) and CD34 (progenitor cells) followed by intracellular staining with PE-conjugated anti-TNFα. Figure shows the relative TNFα expression for each of the specific BM populations. Results are expressed as mean +/− S.D. of three independent experiments. **P < 0.001 or *P < 0.01 or #P < 0.05 vs “+ IL-1β − SCIO-469”.

2. Secretion of TNF requires p38 MAPK-dependent interactions between stromal and mononuclear cells

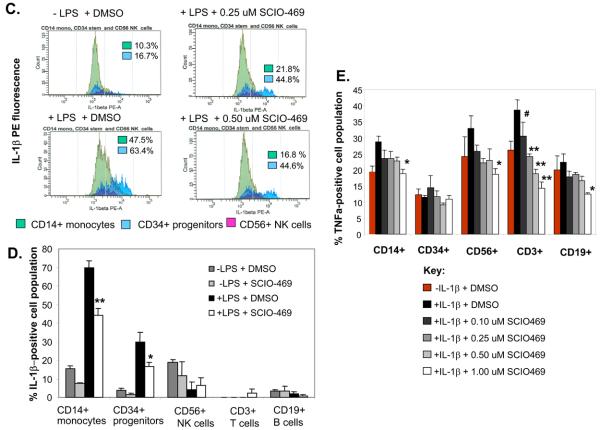

The bone marrow microenvironment and stroma are hypothesized to play an important role in the pathogenesis of MDS though it is not clear if they are intrinsically defective or are just a facilitator of the disease process. We first determined the role of BM stroma in stimulating BM mononuclear cells to secrete TNFα. Primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) were isolated from healthy donors and grown to form an adherent cell line and were cocultured with bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNC) isolated from a different normal donor. BMSC were able to strongly induced TNFα secretion from BMMNC in vitro. This process was p38 MAPK dependent as TNFα production was specifically inhibited by SCIO-469 (Fig. 2A). We further determined the functional differences between stromal cells derived from MDS and healthy controls in stimulating BMMNCs. BM stromal cells were isolated from two different low risk MDS patients whose BM cells have been found to have activated p38 in our previous report [39]. These stromal cells were cocultured with BMMNC isolated from a normal donor. BMSC from MDS patients were capable of inducing normal BMMNC to secrete TNFα at levels similar to those induced by normal BMSC (Fig. 2B), suggesting that they may not be inherently transformed in the disease. Since the bone marrow in MDS comprises many different cell types including stroma and BMMNCs, we next wanted to determine the cumulative role of p38 MAPK inhibiton in primary total MDS bone marrow aspirates ex vivo. Fresh total bone marrow aspirates from 3 patients with MDS (containing mononuclear cells as well as stromal cells) were cultured ex vivo in the presence and absence of SCIO-469 in an attempt to mimic in vivo bone marrow microenvironment in MDS. Intracellular flow cytometry revealed that significant levels of TNFα was secreted by CD14+ cells in MDS BM aspirates and this was inhibited in the presence of SCIO-469 (Fig. 2C). This observation coupled with earlier results suggest that selective inhibition of p38α by SCIO-469 inhibits the production of TNFα in total BM aspirates isolated from MDS patients by disrupting the BMSC-BMMNC paracrine interactions (Fig. 2) as well as directly inhibiting cytokine generation by the mononuclear cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 2. Secretion of TNF requires p38 MAPK-dependent interactions between stromal and mononuclear cells.

A. BMSC and BMMNC from normal donors were either cultured alone or cocultured together for 72h in the presence and absence of 0.5 μM SCIO-469. TNFα concentration in cell supernatants was determined by ELISA. Figure represents Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. B. Similar co-culture experiments were conducted as in (A) but using BMSC derived from either normal healthy control or from low risk MDS patients. Figure represents Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. C. Total bone marrow aspirates isolated from three different MDS patients were assessed for intracellular TNFα production by using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were incubated in the presence of 10 μg/mL of immobilized anti-CD3 mAb plus 2 μg/mL of anti-CD28 antibody with or without 0.5 μM SCIO-469 in the presence of monensin for 6h at 37°C. Addition of anti-CD28 antibody providing costimulation and monensin blocking secretion of the cytokines during the incubation allows sensitive assessment of cytokine-producing cells. After the stimulation, cells were stained with anti-CD14-PE and TNFα-APC before analyzing by flow cytometry. CD14+ cells with intracellular TNF were expressed as a percentage of total CD14+ cells.

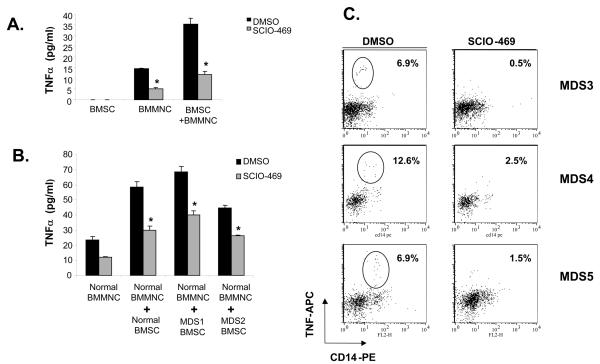

3. CD34+ stem cell apoptosis induced by inflammatory bone marrow cells correlates with TNF secretion

MDS is characterized by increased apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow that leads to ineffective hematopoiesis and low peripheral blood counts. The exact etiology of apoptosis is still unknown. We next wanted to determine the role of TNF production by the bone marrow microenvironment in this process. Primary BM-derived mononuclear cells were cultured in the presence of LPS to simulate an inflammatory BM microenvironment and apoptosis was measured in the CD34+ bone marrow stem cells. Bone marrow MNCs displayed increased CD34+ apoptosis after 48 hours of exposure to LPS (Fig. 3A). The increase in CD34+ apoptosis was effectively inhibited by treatment with increasing concentrations of SCIO-469 (Fig. 3A and 3B). The percentage of viable CD34+ cells inversely correlated with the levels of TNFα secreted in the cell cultures (Fig. 3C). Treatment with SCIO-469 proportionately reduced the levels of TNFα and correspondingly increased the proportion of viable CD34+ progenitors in primary bone marrow cells.

Figure 3. SCIO-469 inhibits LPS-induced CD34+ Apoptosis and TNFα production in normal BMMNC in vitro.

A. BMMNC (1 × 106) from a normal healthy donor were cultured in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of SCIO-469 without or with 10 ng/mL LPS for 48h. Cells were stained with anti-CD34-PE Cy7, anti-CD45-APC Cy7, Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometry using the BD LSR II. Dot plot shows Annexin V-PE (X-axis) and 7-AAD (Y-axis) staining of CD34+ gated cells. B. Bar graph showing percent early apoptotic (Annexin V+, 7-AAD−), late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+, 7-AAD+), and necrotic (Annexin V−, 7-AAD+) in CD34+ gated cell populations. Figures represents Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 or #P < 0.05 vs “+ LPS − SCIO-469”. C. TNF concentration was measured by ELISA in supernatants collected from experiment performed above and correlated with percentage of viable CD34+ cells. Figures represent Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 for DMSO + LPS.

4. TNF and Il-1β can stimulate proinflammatory chemokines in a p38-dependent fashion in the bone marrow

Recent data has implicated chemokines in the migration and activation of proinflammatory leukocytes to the bone marrow in various hematologic diseases [43,44]. Since TNF and IL-1β are important in MDS pathophysiology, we wanted to determine if these two cytokines could also regulate the propagation of inflammation in the bone marrow by influencing chemokine production by the stroma. To also examine whether such mechanism could be regulated by p38, we stimulated BMSC with TNFα or IL-1β for 24 hours in the presence or absence of SCIO-469 and analyzed the gene expression profile in these cells by microarray analysis. We found a number of chemokines that were strongly induced by IL-1β and TNFα and were strongly inhibited by SCIO-469 (Table 1). These include chemokines such as CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MCP-1), CCL7 (MCP-3), CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCL6 (granulocyte chemotactic protein-2), CXCL3 (Gro-gamma), and CXCL1 (Gro-alpha). Most of these chemokines have been recently implicated in promoting adhesion of leukocytes to BM stromal cells [45] and our data implicate p38 MAPK in another inflammatory pathway in the bone marrow microenvironment.

Table 1.

Gene Microarray Analysis of Chemokines Induced by IL-1β and inhibited by SCIO-469 in BMSC

| Symbol | Other Name | Name | IL-1β (24hr) * | SCIO-469 + IL1β (24hr) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1 | GRO | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 1 | 125.9 | −1.6 |

| CCL2 | MCP-1 | Chemokine (CC) ligand 2 | 9.9 | −1.4 |

| CXCL6 | GCP2 | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 6 | 138.8 | −1.6 |

| CXCL3 | GROγ | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 3 | 40.6 | 1.3 |

| CCL7 | MCP3 | Chemokine (CC) ligand 7 | 6.2 | −1.5 |

| CXCL10 | IP10 | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 10 | 1 | 1 |

| CXCL11 | ITAC | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 11 | 1 | 0 |

| CXCL16 | SR-PSOX | Chemokine (CXC) ligand 16 | 9.3 | −4.2 |

Fold change of gene expression over control unstimultaed BMSCs

Fold change of gene expression over IL-1beta stimulated BMSCs

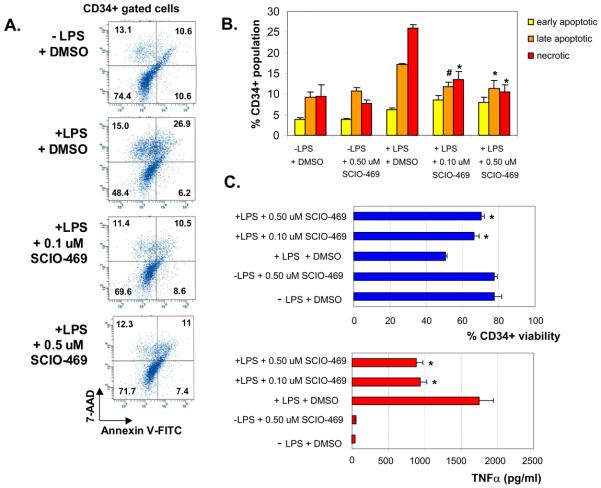

5. SCIO-469 can protect normal stem cell clones from apoptosis in MDS

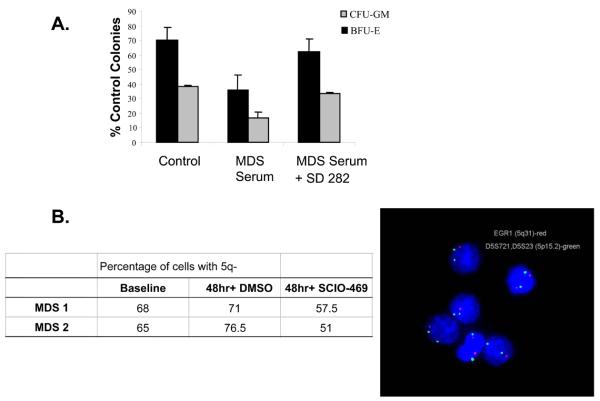

To demonstrate the collective effect of all these proinflammatory cytokines in inhibiting hematopoiesis, normal CD34+ stem cells were incubated with fresh BM-derived sera from 3 MDS patients and assessed for erythroid and myeloid colony formation (Fig. 4A). We determined that MDS sera was able to suppress both Blast Forming Unit-Erythroid (BFU-E) and Colony Forming Unit-Granulocytic-Monocytic (CFU-GM) colonies when compared to the effects of normal BM serum derived from healthy controls. Inhibition of p38 with another specific p38α inhibitor SD-282 [46] resulted in increases of both BFU-E and CFU-GM colony numbers similar to those found in normal controls. These results suggest that inhibitory factors present in MDS sera can activate p38 MAPK in normal CD34+ cells resulting in decreased hematopoiesis.

Figure 4. SCIO-469 can protect normal stem cell clones from apoptosis in MDS.

A. Normal CD34+ cells obtained from healthy volunteer were grown in methylcelluose in the presence 100 μL of primary bone marrow sera obtained from bone marrows of 3 MDS patients. These experiments were done in the presence or absence of 100 nM SD-282. Erythroid and Myeloid colonies were counted after 14 days. Mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments are shown. B. BMMNC from 2 patients with MDS with chromosome 5q deletion were cultured in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM SCIO-469 for 48h. Cells were fixed onto slides pre- and post-treatment and used for fluorescent in situ hybridization using EGR-1 probe (5q31-RED) to detect the number of abnormal clones. A 5p15 centromeric (GREEN) probe was used as internal control. 200 cells per slide were counted and result expressed as percentage.

Since both normal and malignant stem cell clones are found to coexist in MDS bone marrows, it is very important to determine which of these are targets of proinflammatory cytokines in the marrow and are rescued by p38 inhibition. To evaluate this, we treated bone marrow MNCs from two MDS patients with chromosome 5q deletion with SCIO-469 in vitro. Cells harboring the 5q deletion belonged to the abnormal clone and were found to comprise 65-68% of the bone marrow mononuclear cells by FISH analysis. Treatment with p38 inhibitor for 48 hrs led to a decrease in the percentage of cells with 5q- deletion in both cases (Fig. 4B). Since we have shown earlier that similar treatment with SCIO-469 increases the number of total viable MDS bone marrow progenitor cells [39], we believe this clonogenic data suggests that p38 inhibition may be rescuing the cytogenetically normal cells from apoptosis.

Discussion

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are considered potent paracrine mediators of ineffective hematopoiesis in MDS. Our studies show that SCIO-469, a selective inhibitor of p38α MAPK, effectively inhibits the production of several proinflammatory proteins implicated in the pathobiology of MDS. These cytokines include the proinflammatory and myelosuppresive cytokines such as IL-1β (Fig. 2 and 3) and TNFα (Fig. 3-5) as well as inflammatory chemokines that recruit and activate cytokine-secreting inflammatory cells to the local site of inflammation in the BM [3]. TNFα can directly induce CD34+ apoptosis through the activation of p38 MAPK [40,47]. IL 1β, which is secreted by BM macrophages and proliferating myeloblasts, has been linked to more aggressive biologic behavior of leukemia [18,19]. Moreover, TNFα and IL-1β levels have been correlated with the cause of anemia by suppressing the growth of mature erythroid colony forming units (CFU-E) and by inhibiting the effects of erythroipoietin (Epo) on red blood cell development [48,49]. In addition to its direct effects, IL-1β also induces the production of TNFα and Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), both potent suppressors of the myeloid stem cell development [20]. We have shown that IL-1β-induced TNFα expression is regulated by p38 MAPK and inhibited by SCIO-469 in primary BM monocytes and T cells. TNFα has also been shown to induce IL-1β through the activation of NFκB [50], and TNFα-induced NFκB activation, in turn, has been shown to be regulated by p38 MAPK [51]. In addition to regulating transcription, p38 MAPK has also been shown to regulate post transcriptional modification of TNFα and IL-1β, through message stabilization involving MapKapk-2 [52]. Thus our data is consistent with previous reports of crosstalk between various inflammatory cytokine signaling pathways and demonstrates the central role of p38 MAPK activation in this network in primary human hematopoietic cells.

TNFα and IL-1β induce the secretion of a number of inflammatory chemokines by the bone marrow stroma in a p38-dependent manner. These chemokines serve as chemoattractants for leukocytes, particularly monocytes, T cells and granulocytes, to the local sites of inflammation, which could lead to the amplification of the inflammatory signal found in chronic inflammation [45]. Recent data have shown that chemokines and their receptors are involved in regulating hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis [44] and in the pathogenesis of various bone marrow diseases [43]. Collectively, our data implicate p38 MAPK in multiple autocrine and paracrine cytokine loops that are activated in MDS bone marrows.

In addition to MDS, stromal cell-mediated production of cytokines has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of other hematologic diseases such as multiple myeloma [22,23] and idiopathic myelofibrosis [24]. It is still unclear if stromal cells in MDS have a primary defect [25-28] or are just innocent bystanders [7,29,30]. Our data demonstrate that primary stromal cells from 2 MDS patients are functionally similar to those from healthy volunteers, with regards to the levels of TNF production. Our data also demonstrate that interactions between hematopoietic progenitors and stromal cells are very important mediators of cytokine production in the bone marrow. Thus agents that disrupt inflammatory stromal cell interactions with abnormal hematopoietic stem cell clones can be potential therapeutic targets in certain subsets of MDS.

MDS is a clonal hematologic malignancy, and at the low grade stage of the disease, both normal and cytogenetically abnormal hematopoietic clones are found to exist in the marrow [53]. Previous reports have shown that abnormal MDS progenitor clones have higher levels of anti apoptotic proteins such as bcl-2, are resistant to apoptosis, and behave similarly to leukemic cells [54]. We have previously shown that p38 inhibition can expand total numbers of CD34+ cells from MDS patients [39]. In the present study, we show direct evidence that treatment with p38 inhibitors can reduce the numbers of stem cell clones with 5q chromosomal deletion. Taken together, these data imply that p38 inhibition rescues the normal stem cell clones in MDS. This observation has important implications for translation research efforts with SCIO-469 in MDS. A new immunomodulatory drug, lenalidomide (Revlimid), has shown remarkable clinical efficacy in MDS subsets with deletion of chromosome 5q [55,56]. Treatment with this drug leads to reductions in the abnormal stem cell clones in 47% of patients, but the exact mechanism of action is unknown. It is known that lenalidomide leads to alterations in functions of immune and NK cells and can alter the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance [3,57,58]. Thus our similar in vitro observations with p38 inhibition in two patient samples with 5q- MDS may reiterate the role of cytokine dysregulation in the pathogenesis of this clinically important subset of MDS.

Altogether, our results demonstrate that in addition to its direct anti-apoptotic effects on CD34+ stem cells, SCIO-469 also inhibits the expression of various proinflammatory factors in the bone marrow and disrupts the inflammatory loop that leads to the pleiotropic production of such factors. SCIO-469 is presently being used in a Phase I/II clinical trial in low grade cases of MDS. Early results have shown some efficacy in this disease [59]. Due to the multiple cytokine pathways implicated in MDS pathogenesis, strategies to selectively inhibit individual cytokines and their receptors have not yielded much success in this disease [60]. Our data demonstrates that p38 MAPK may represent a common signaling pathway used by multiple cytokine pathways in MDS and thus may be an attractive therapeutic target in this disease.

Acknowledgements

SCIOS: We would like to thank Bruce Koppelmann, Jing Ying Ma, Heather Maecker, Gilbert O'Young, Yu-Wang Liu, and Ann M. Kapoun for their contributions to this project.

Supported by NIH 1R01HL082946-01, Community Foundation of Southeastern Michigan JP Mccarthy fund award, NIH RO1 AG029138 and Immunology and Immunooncology Training Program T32 CA009173

Reference

- 1.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, Sanz M, Vallespi T, Hamblin T, Oscier D. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–88. and others. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaney ML, Golde DW. Myelodysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1649–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma A, List AF. Cytokine targets in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Curr Hematol Rep. 2005;4:429–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allampallam K, Shetty V, Mundle S, Dutt D, Kravitz H, Reddy PL, Alvi S, Galili N, Saberwal GS, Anthwal S. Biological significance of proliferation, apoptosis, cytokines, and monocyte/macrophage cells in bone marrow biopsies of 145 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Hematol. 2002;75:289–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02982044. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claessens YE, Park S, Dubart-Kupperschmitt A, Mariot V, Garrido C, Chretien S, Dreyfus F, Lacombe C, Mayeux P, Fontenay M. Rescue of early stage myelodysplastic syndrome-deriving erythroid precursors by the ectopic expression of a dominant negative form of FADD. Blood. 2005 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zorat F, Shetty V, Dutt D, Lisak L, Nascimben F, Allampallam K, Dar S, York A, Gezer S, Venugopal P. The clinical and biological effects of thalidomide in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:881–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03204.x. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeg HJ, Beckham C, Loken MR, Bryant E, Lesnikova M, Shulman HM, Gooley T. Negative regulators of hemopoiesis and stroma function in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:405–14. doi: 10.3109/10428190009089441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allampallam K, Shetty V, Hussaini S, Mazzoran L, Zorat F, Huang R, Raza A. Measurement of mRNA expression for a variety of cytokines and its receptors in bone marrows of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:5323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundle SD, Reza S, Ali A, Mativi Y, Shetty V, Venugopal P, Gregory SA, Raza A. Correlation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF alpha) with high Caspase 3-like activity in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Lett. 1999;140:201–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufour C, Corcione A, Svahn J, Haupt R, Battilana N, Pistoia V. Interferon gamma and tumour necrosis factor alpha are overexpressed in bone marrow T lymphocytes from paediatric patients with aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:1023–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welsh JP, Rutherford TR, Flynn J, Foukaneli T, Gordon-Smith EC, Gibson FM. In vitro effects of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on CD34+ bone marrow progenitor cells from aplastic anemia patients and normal donors. Hematol J. 2004;5:39–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike M, Ishiyama T, Tomoyasu S, Tsuruoka N. Spontaneous cytokine overproduction by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and aplastic anemia. Leuk Res. 1995;19:639–44. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00044-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dufour C, Corcione A, Svahn J, Haupt R, Poggi V, Beka'ssy AN, Scime R, Pistorio A, Pistoia V. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma are overexpressed in the bone marrow of Fanconi anemia patients and TNF-alpha suppresses erythropoiesis in vitro. Blood. 2003;102:2053–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa M, Saito I, Kuwata T, Yoshida S, Yamaguchi S, Takahashi M, Tanizawa T, Kamiyama R, Hirokawa K. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interferon (IFN)-gamma by bone marrow cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 1997;11:2049–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellamy WT, Richter L, Sirjani D, Roxas C, Glinsmann-Gibson B, Frutiger Y, Grogan TM, List AF. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor is an autocrine promoter of abnormal localized immature myeloid precursors and leukemia progenitor formation in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2001;97:1427–34. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabrilovich D, Ishida T, Oyama T, Ran S, Kravtsov V, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Blood. 1998;92:4150–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aguayo A, Kantarjian H, Manshouri T, Gidel C, Estey E, Thomas D, Koller C, Estrov Z, O'Brien S, Keating M. Angiogenesis in acute and chronic leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2000;96:2240–5. and others. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurzrock R, Kantarjian H, Wetzler M, Estrov Z, Estey E, Troutman-Worden K, Gutterman JU, Talpaz M. Ubiquitous expression of cytokines in diverse leukemias of lymphoid and myeloid lineage. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffin JD, Rambaldi A, Vellenga E, Young DC, Ostapovicz D, Cannistra SA. Secretion of interleukin-1 by acute myeloblastic leukemia cells in vitro induces endothelial cells to secrete colony stimulating factors. Blood. 1987;70:1218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagby GC., Jr Interleukin-1 and hematopoiesis. Blood Rev. 1989;3:152–61. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(89)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigorieva I, Thomas X, Epstein J. The bone marrow stromal environment is a major factor in myeloma cell resistance to dexamethasone. Exp Hematol. 1998;26:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui H, Hideshima T, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Novel therapeutic strategies targeting growth factor signalling cascades in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:385–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tefferi A. Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1255–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores-Figueroa E, Arana-Trejo RM, Gutierrez-Espindola G, Perez-Cabrera A, Mayani H. Mesenchymal stem cells in myelodysplastic syndromes: phenotypic and cytogenetic characterization. Leuk Res. 2005;29:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narendran A, Hawkins LM, Ganjavi H, Vanek W, Gee MF, Barlow JW, Johnson G, Malkin D, Freedman MH. Characterization of bone marrow stromal abnormalities in a patient with constitutional trisomy 8 mosaicism and myelodysplastic syndrome. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;21:209–21. doi: 10.1080/08880010490276917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauro S, Hepburn MD, Bowen DT, Pippard MJ. Assessment of stromal function, and its potential contribution to deregulation of hematopoiesis in the myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2001;86:1038–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aizawa S, Nakano M, Iwase O, Yaguchi M, Hiramoto M, Hoshi H, Nabeshima R, Shima D, Handa H, Toyama K. Bone marrow stroma from refractory anemia of myelodysplastic syndrome is defective in its ability to support normal CD34-positive cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Leuk Res. 1999;23:239–46. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deeg HJ. Marrow stroma in MDS: culprit or bystander? Leuk Res. 2002;26:687–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aizawa S, Hiramoto M, Hoshi H, Toyama K, Shima D, Handa H. Establishment of stromal cell line from an MDS RA patient which induced an apoptotic change in hematopoietic and leukemic cells in vitro. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:148–55. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young NS, Maciejewski J. The pathophysiology of acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1365–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705083361906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kook H, Zeng W, Guibin C, Kirby M, Young NS, Maciejewski JP. Increased cytotoxic T cells with effector phenotype in aplastic anemia and myelodysplasia. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1270–7. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selleri C, Maciejewski JP, Catalano L, Ricci P, Andretta C, Luciano L, Rotoli B. Effects of cyclosporine on hematopoietic and immune functions in patients with hypoplastic myelodysplasia: in vitro and in vivo studies. Cancer. 2002;95:1911–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sloand EM, Mainwaring L, Fuhrer M, Ramkissoon S, Risitano AM, Keyvanafar K, Lu J, Basu A, Barrett AJ, Young NS. Preferential suppression of trisomy 8 versus normal hematopoietic cell growth by autologous lymphocytes in patients with trisomy 8 myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2005 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloand EM, Pfannes L, Chen G, Shah S, Solomou EE, Barrett J, Young NS. CD34 cells from patients with trisomy 8 myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) express early apoptotic markers but avoid programmed cell death by up-regulation of antiapoptotic proteins. Blood. 2007;109:2399–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-030643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar S, Boehm J, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:717–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Platanias LC. Map kinase signaling pathways and hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;101:4667–79. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navas TA, Mohindru M, Estes M, Ma JY, Sokol L, Pahanish P, Parmar S, Haghnazari E, Zhou L, Collins R. Inhibition of overactivated p38 MAPK can restore hematopoiesis in myelodysplastic syndrome progenitors. Blood. 2006;108:4170–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023093. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma A, Deb DK, Sassano A, Kambhampati S, Wickrema A, Uddin S, Mohindru M, Van Besien K, Platanias LC. Cutting edge: activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway mediates cytokine-induced hemopoietic suppression in aplastic anemia. J Immunol. 2002;168:5984–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohindru M, Kang B, Kim BS. Initial capsid-specific CD4(+) T cell responses protect against Theiler's murine encephalomyelitisvirus-induced demyelinating disease. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2106–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim MY, Wang H, Kapoun AM, O'Connell M, O'Young G, Brauer HA, Luedtke GR, Chakravarty S, Dugar S, Schreiner GS. p38 Inhibition attenuates the pro-inflammatory response to C-reactive protein by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:1111–4. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.09.015. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haneline LS, Broxmeyer HE, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Carreau M, Buchwald M, Clapp DW. Multiple inhibitory cytokines induce deregulated progenitor growth and apoptosis in hematopoietic cells from Fac−/− mice. Blood. 1998;91:4092–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devine SM, Flomenberg N, Vesole DH, Liesveld J, Weisdorf D, Badel K, Calandra G, DiPersio JF. Rapid mobilization of CD34+ cells following administration of the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 to patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1095–102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.List AF. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway as an emerging target in hematologic malignancies. Oncologist. 2001;6(Suppl 5):24–31. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_5-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nath P, Leung SY, Williams A, Noble A, Chakravarty SD, Luedtke GR, Medicherla S, Higgins LS, Protter A, Chung KF. Importance of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in allergic airway remodelling and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;544:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma A, Deb DK, Sassano A, Uddin S, Varga J, Wickrema A, Platanias LC. Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates the suppressive effects of type I interferons and transforming growth factor-beta on normal hematopoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7726–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Means RT, Jr., Dessypris EN, Krantz SB. Inhibition of human erythroid colony-forming units by interleukin-1 is mediated by gamma interferon. J Cell Physiol. 1992;150:59–64. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jelkmann W, Wolff M, Fandrey J. Modulation of the production of erythropoietin by cytokines: in vitro studies and their clinical implications. Contrib Nephrol. 1990;87:68–77. doi: 10.1159/000419481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werner SL, Barken D, Hoffmann A. Stimulus specificity of gene expression programs determined by temporal control of IKK activity. Science. 2005;309:1857–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1113319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brinkman BM, Telliez JB, Schievella AR, Lin LL, Goldfeld AE. Engagement of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 leads to ATF-2- and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent TNF-alpha gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30882–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotlyarov A, Neininger A, Schubert C, Eckert R, Birchmeier C, Volk HD, Gaestel M. MAPKAP kinase 2 is essential for LPS-induced TNF-alpha biosynthesis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:94–7. doi: 10.1038/10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Legare RD, Gilliland DG. Myelodysplastic syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol. 1995;2:283–92. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199502040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenberg PL. Apoptosis and its role in the myelodysplastic syndromes: implications for disease natural history and treatment. Leuk Res. 1998;22:1123–36. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, Giagounidis A, Raza A, Feldman E, Powell B, Greenberg P, Thomas D, Stone R. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.List A, Gewald G, Bennett J, Giagounadis A, Raza A, Feldman E, Powell B, Greenberg P, Faleck H, Zeldis J. Results of the MDS-002 and -003 international phase II studies evaluating lenalidomide (CC-5013; Revlimid*) in the treatment of transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) Haematologica. 2005;90:307a. and others. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tai YT, Li XF, Catley L, Coffey R, Breitkreutz I, Bae J, Song W, Podar K, Hideshima T, Chauhan D. Immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide (CC-5013, IMiD3) augments anti-CD40 SGN-40-induced cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma: clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11712–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1657. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson KC. Lenalidomide and thalidomide: mechanisms of action--similarities and differences. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:S3–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sokol L, Cripe L, Kantarjian H, Sekeres M, Parmar S, Greenberg P, Goldberg S, Bhushan V, Shammo J, Hohl R. Phase I/II, Randomized, MultiCenter MultiCenter, Dose, Dose-Ascension Study of the p38 MAPK inhibitor Ascension Study of the p38 MAPK inhibitor Scio Scio-469 in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) 469 in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) American Society of Hematology. 2006;108:Poster 2657. and others. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raza A, Candoni A, Khan U, Lisak L, Tahir S, Silvestri F, Billmeier J, Alvi MI, Mumtaz M, Gezer S. Remicade as TNF suppressor in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:2099–104. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001723322. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]