Abstract

Summary: Founded upon diffusion with damping, ITM Probe is an application for modeling information flow in protein interaction networks without prior restriction to the sub-network of interest. Given a context consisting of desired origins and destinations of information, ITM Probe returns the set of most relevant proteins with weights and a graphical representation of the corresponding sub-network. With a click, the user may send the resulting protein list for enrichment analysis to facilitate hypothesis formation or confirmation.

Availability: ITM Probe web service and documentation can be found at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CBBresearch/qmbp/mn/itm_probe

Contact: yyu@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

1 INTRODUCTION

Protein interaction networks are presently under intensive research (Bader et al., 2008). Recently, a number of authors have applied the concept of random walk (with truncation) to extract biologically relevant information from protein interaction networks (Nabieva et al., 2005; Suthram et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2006). These approaches, however, do not model information loss/leakage that naturally occurs in all networks. For example, in cellular networks, proteases constantly degrade proteins, diminishing the strength of information propagation. We have recently developed a mathematical framework to model information flow in interaction networks with a novel ingredient, damping/aging of information (Stojmirović and Yu, 2007). Implementing the theory, we have constructed a web application ITM Probe, which also contains a new model of information propagation: the information channel.

ITM Probe models information flow in a protein interaction network through discrete time random walks. Unlike classical random walks, our model allows the walker a certain probability to dissipate or damp (that is, to leave the network) at each step. Each walk, simulating a possible information path, terminates either by dissipation or by reaching a boundary node.

We distinguish two types of boundary nodes: sources (emitting information) and sinks (absorbing information). ITM Probe offers three models: absorbing, emitting and channel. For any network node, the corresponding weight returned by the emitting model is the expected number of visits to that node by a random walk originating at given source(s). The absorbing model, on the other hand, returns the likelihood of a random walk starting at that node to terminate at sink(s). The channel model contains both sources and sinks as boundary and reports the expected numbers of visits to any network node from random walks originating at sources and terminating at sinks.

Each selection of boundary nodes and dissipation rates provides the biological context for the information transmission modeled. Small dissipation allows random walks to explore the nodes farther away from their origin, while large dissipation evaporates quickly most walks. For the channel model, dissipation controls how much a random walk can deviate from the shortest path from sources to sinks. We call the set of most significant nodes, in terms of the weights returned, an Information Transduction Module (ITM).

2 USAGE

Both the absorbing and emitting models navigate neighborhoods of selected nodes and illuminate the protein complexes associated with them. However, the absorbing model can reveal relatively distant ‘leaf’ nodes linked to a sink by a nearly unique path, while the emitting model favors highly connected clusters. The channel model combines both the emitting and absorbing models and enables information flow through neighboring but distinct complexes with certain directionality. It is suited for discovery of potential pathways linking proteins of interest or biological functions associated with them. For example, setting a membrane receptor as a source and a transcription factor as a sink may shed light on a potential signal transduction pathway, which can be validated experimentally. Using multiple sources may reveal the potential points of crosstalk between information channels, while a solution of multiple sinks chosen according to a set of competing hypotheses may suggest most biologically plausible pathways among many possible ones.

Every model of ITM Probe requires an interaction graph, the boundary nodes (sources and/or sinks) and the damping factors as input. The damping factors may be specified directly or by setting the desired average path length (emitting/channel model) or the average likelihood of absorption at sinks (absorbing model).

Although our mathematical framework can be applied to any directed graph, our web service presently supports only the yeast, human and fruit fly physical interaction networks derived from the BioGRID (Stark et al., 2006) database. The yeast network has the best coverage/quality and we offer three versions of it: Full, Reduced and Directed. The Full network consists of all interactions from the BioGRID as an undirected graph, while the Reduced consists only of those interactions that are from low-throughput experiments (that is, from publications reporting less than 300 interactions) or are reported by at least two independent publications. The Directed network is derived from Reduced by turning all interactions labeled as ‘Biochemical activity’ into directed links (bait → prey) and is thus suitable for exploring signaling cascades, for example, by phosphorylation. For human and fruit fly, only the Full networks are presently provided.

To assist in silico investigations on the impact of knocking out certain genes, ITM Probe allows users to specify nodes to exclude from the network. Furthermore, it is known (Steffen et al., 2002) that proteins with a large number of non-specific interaction partners might overtake the true signaling proteins in the information flow modeling. Therefore, ITM Probe by default excludes from the yeast networks the proteins that may provide undesirable shortcuts, such as cytoskeleton proteins, histones and chaperones. The user may choose to lengthen or shorten this list.

2.1 Output and analysis

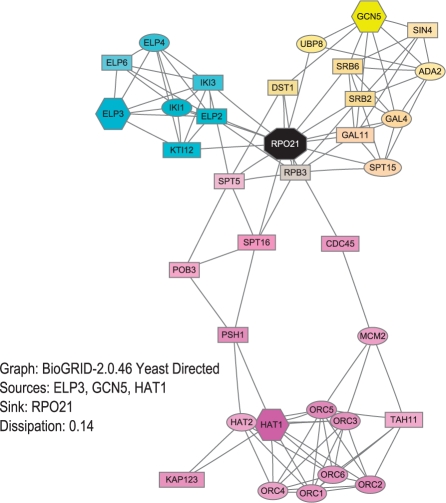

ITM Probe outputs a list of the top ranking nodes together with an image of the sub-network consisting of these nodes (Fig. 1). Images are produced using the Graphviz suite (Gansner and North, 2000). Each protein listed is linked to its full description in several external databases. The number of nodes to be listed can be specified directly by the user or determined automatically from the model results through a criterion such as participation ratio (Stojmirović and Yu, 2007) or the cutoff value. The resulting weights for all nodes can be downloaded in the CSV format for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

An example ITM from running the ITM Probe channel model.

Each ITM image can be rendered and saved in multiple formats (SVG, PNG, JPEG, EPS and PDF). For each rendering, the users can choose which aspects of results to display, the color map and the scale for presentation (linear or logarithmic). When multiple boundary points are specified, it is possible to obtain an overview of all of their contributions simultaneously by selecting the color mixture scheme (Fig. 1). In this case, each source (channel/emitting model) or sink (absorbing model) is assigned a basic CMY (cyan, magenta or yellow) color and the coloring of each displayed node is a result of mixing the colors corresponding to its source- or sink- specific values for each of the boundary points.

While it is possible to specify any proteins in the network as sources and sinks, not every context produces biologically meaningful results. To facilitate biological interpretation of the users' results, we have locally implemented a Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000) enrichment tool based on GO::TermFinder of Boyle et al. (2004). It compares a given input list of proteins to the lists annotated with GO terms and finds those GO terms that statistically best explain the input list. Every ITM Probe results page contains a query form allowing the user to specify the number of the top ranking proteins to consider for GO-term enrichment analysis.

2.2 Example

Histone acetyltransferases remodel chromatin by acetylating histone octamers and hence may play an important role in transcription activation (Sterner and Berger, 2000). To explore the interface between them and the RNA Polymerase II core in yeast, we choose three histone acetyltransferases (Hat1p, Gcn5p, Elp3p) as sources and a catalytic subunit Rpo21p of RNA Polymerase II as a sink for the channel model (Fig. 1). From the color mixing image it appears that Elp3p and Gcn5p interact with Rpo21p through a wide channel of proteins, while Hat1p seems to be remote from Rpo21p. This prompts the hypothesis that Hat1p is not directly involved in transcription activation. Enrichment analysis, using the 16 nodes (shown in magenta color in Fig. 1) mostly visited from Hat1p, shows that Hat1p and these nodes participate mainly in DNA replication and only indirectly in transcription regulation, thus reinforcing the hypothesis. Similar analysis on the nodes associated with Elp3p indicates that the interaction is almost exclusively through the elongator complex. The nodes associated with Gcn5p are less specific, indicating a more generic interface, but are all involved mRNA transcription.

3 OUTLOOK

We plan to include additional genetic and physical interaction networks from a variety of organisms. In principle, the analysis from ITM Probe can be integrated with existing partial knowledge to form a broad picture of possible communication paths in cellular processes. The concept of context-specific analysis may find applications beyond biological networks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ITM Probe implementation relies on a variety of open source projects, which we acknowledge on our web site.

Funding: Intramural Research Program of the National Library of Medicine at National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader S, et al. Interaction networks for systems biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1220–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle EI, et al. GO::TermFinder—open source software for accessing gene ontology information and finding significantly enriched gene ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansner ER, North SC. An open graph visualization system and its applications to software engineering. Software—Practice and Experience. 2000;30:1203–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Nabieva E, et al. Whole-proteome prediction of protein function via graph-theoretic analysis of interaction maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl. 1):302–310. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, et al. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D535–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen M, et al. Automated modelling of signal transduction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojmirović A, Yu Y-K. Information flow in interaction networks. J. Comput. Biol. 2007;14:1115–1143. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2007.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthram S, et al. eQED: an efficient method for interpreting eQTL associations using protein networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:162. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, et al. An integrative approach for causal gene identification and gene regulatory pathway inference. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e489–e496. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]