Abstract

Motivation: In silico prediction of drug–target interactions from heterogeneous biological data is critical in the search for drugs for known diseases. This problem is currently being attacked from many different points of view, a strong indication of its current importance. Precisely, being able to predict new drug–target interactions with both high precision and accuracy is the holy grail, a fundamental requirement for in silico methods to be useful in a biological setting. This, however, remains extremely challenging due to, amongst other things, the rarity of known drug–target interactions.

Results: We propose a novel supervised inference method to predict unknown drug–target interactions, represented as a bipartite graph. We use this method, known as bipartite local models to first predict target proteins of a given drug, then to predict drugs targeting a given protein. This gives two independent predictions for each putative drug–target interaction, which we show can be combined to give a definitive prediction for each interaction. We demonstrate the excellent performance of the proposed method in the prediction of four classes of drug–target interaction networks involving enzymes, ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and nuclear receptors in human. This enables us to suggest a number of new potential drug–target interactions.

Availability: An implementation of the proposed algorithm is available upon request from the authors. Datasets and all prediction results are available at http://cbio.ensmp.fr/~yyamanishi/bipartitelocal/.

Contact: kevbleakley@gmail.com

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The search for interactions between compounds (ligands, molecules, drugs) and proteins (targets) is an important part of genomic drug discovery. Interactions with compounds can affect the action of many classes of pharmaceutically useful protein targets including enzymes, ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and nuclear receptors. High-throughput experiments analyzing the genome, transcriptome and proteome are beginning to lead to the understanding of genomic spaces populated by these classes of protein. Simultaneously, high-throughput screening of large chemical compound libraries enables us to explore the chemical space of possible compounds (Dobson, 2004; Kanehisa et al., 2006; Stockwell, 2000). Chemical genomics research aims to relate the chemical space with the genomic space in order to identify potentially useful compound–protein pairs. This said, our current knowledge about the relationship between these spaces is relatively limited. The PubChem database at NCBI (Wheeler et al., 2006), for example, stores information on millions of chemical compounds, but the number of compounds linked to target proteins remains very small. There is, therefore, a strong incentive to develop new methods that are able to predict new compound–protein interactions.

Experimental determination of compound–protein interactions remains challenging (Haggarty et al., 2003; Kuruvilla et al., 2002). It is thus of great practical interest to develop genuinely effective in silico prediction methods which can both provide new predictions to experimentalists and provide supporting evidence to experimental results. A variety of such approaches have been developed to analyze and predict compound–protein interactions. One of the most commonly used is docking simulations (Cheng et al., 2007; Rarey et al., 1996). This is relevant when the 3D structure of a protein is already known, which is unfortunately not often the case, limiting large-scale implementation. Keiser et al. (2007) provided a method to predict target protein families based on the known structures of a set of ligands. However, their approach does not take advantage of available sequence information of proteins and predicted interactions were limited to those between known ligands and different protein families. Another interesting approach by Campillos et al. (2008) was the use of similarities in the side-effects of known drugs to predict new drug–target interactions, some of which were verified by in vitro binding assays. The limitation of this approach is that it only applies to known side-effects of known drugs, thus limiting the ability of the method to perform high-throughput screening of potential interactions between new molecules and proteins.

The current state-of-the-art involves integrative methods that simultaneously take into account such things as target protein sequences, drug chemical structures and the currently known drug–target network. Indeed, Yamanishi et al. (2008) and Yamanishi (2009) developed supervised learning algorithms to infer unknown drug–target interactions by integrating the chemical space (e.g. drug chemical structures) and genomic space (e.g. target protein sequences) into a unified space which they call the ‘pharmacological space’. Another encouraging ‘integrative’ research direction is the kernel-based approach (Jacob and Vert, 2008; Nagamine and Sakakibara, 2007) for predicting compound–protein interaction pairs using a binary classification framework. In this context, compound–protein pairs are taken as inputs for classifiers such as support vector machines (SVMs) with pairwise kernels (pairwise SVMs). One serious problem with pairwise SVMs is that the complexity of the ‘training’ phase scales with the square of the ‘number of training ligands times the number of training proteins’, leading to prohibitive computational difficulties for large-scale problems.

In this article, we propose a novel supervised method to predict unknown drug–target interactions from chemical and genomic data that combines the best features of each of these state-of-the-art techniques; we implement a kernel-based method [e.g. as for Jacob and Vert, (2008)], but with the computational simplicity of the work of Yamanishi et al. (2008). Our method involves an extension of the concept of local models (Bleakley et al., 2007; Mordelet and Vert, 2008) to the bipartite network problem and we use it to learn and predict protein–compound interaction networks. Local models are a way to transform edge-prediction problems into well-known binary classification problems of points with labels. Versions of local models have previously been very successful in learning and predicting protein–protein interaction and metabolic networks (Bleakley et al., 2007) and regulatory networks (Mordelet and Vert, 2008).

We then apply the bipartite local models (BLMs) approach to make predictions for four classes of important drug–target interactions in human, involving enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs and nuclear receptors. The proposed method is shown to give superior performance to precursor algorithms of those proposed recently for drug–target interactions in Yamanishi et al. (2008). Indeed, we obtained AUC (area under ROC) scores of >97% in some cases and, more importantly from a biological point of view, AUPR (area under precision–recall) scores of up to 84%. For example, for the ion channel benchmark dataset with 1476 known drug–target interactions (out of a possible 42 840), this meant that we achieved nearly 90% precision at 60% recall. Using an idea that came out of the BLM approach, we then slightly modified the comparison method (Yamanishi et al., 2008) and were able to improve their own AUC and AUPR scores in certain situations. Simple schemes for combining BLM predictions and those of the other method usually further improved AUC and AUPR results. A comprehensive prediction of the four drug–target interaction networks then enabled us to suggest several new potential drug–target interactions.

2 MATERIALS

2.1 Drug–target interaction data

We obtained information about the interactions between drugs and target proteins from the KEGG BRITE (Kanehisa et al., 2006), BRENDA (Schomburg et al., 2004), SuperTarget (Gunther et al., 2008) and DrugBank (Wishart et al., 2008) databases. At the time of writing of Yamanishi et al. (2008), the number of known drugs targeting enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs and nuclear receptors was found to be 445, 210, 223 and 54, respectively. The number of target proteins in these classes was found to be 664, 204, 95 and 26 and the number of known interactions was 2926, 1476, 635 and 90, respectively. We worked with this exact same dataset as Yamanishi et al. (2008) in order to facilitate benchmark comparisons between the two methods. Further details on the curation of these data along with various statistics on the properties of the four drug–target interaction networks are given in Yamanishi et al. (2008).

2.2 Chemical data

Chemical structures of the compounds came from the DRUG and COMPOUND sections in the KEGG LIGAND database (Kanehisa et al., 2006). We computed the chemical structure similarity between compounds using SIMCOMP (Hattori et al., 2003), which provides a global similarity score based on the size of common substructures between compounds using a graph alignment algorithm. In this algorithm, the similarity between compounds c and c′ is given by sc(c, c′)=|c∩c′|/|c∪c′|. Applying this operation to all compound pairs, we constructed a similarity matrix denoted by Sc, which is considered to represent the chemical space.

2.3 Genomic data

Amino acid sequences of the target proteins were obtained from the KEGG GENES database (Kanehisa et al., 2006). In this study, we focused on human proteins. We computed sequence similarities between proteins using a normalized version of Smith–Waterman scores (Smith and Waterman, 1981). The normalized Smith–Waterman score between two proteins g and g′ is given by  , where SW(·, ·) means the original Smith–Waterman score. Applying this operation to all protein pairs, we constructed a similarity matrix denoted Sg, which is considered to represent the genomic space.

, where SW(·, ·) means the original Smith–Waterman score. Applying this operation to all protein pairs, we constructed a similarity matrix denoted Sg, which is considered to represent the genomic space.

3 METHODS

3.1 The problem of supervised bipartite graph prediction

We consider the problem of predicting new edges in a partially known drug–target bipartite network using side information about the vertices. More precisely, we consider the following framework. Suppose that we have a set Vd={d1, d2,…, dm} of drugs (or potential drugs) and a set Vt={t1, t2,…, tn} of target (or potential target) proteins. Suppose further that each drug di and target tj is characterized by a set of pertinent biological data. We make no restriction requiring that drugs be characterized by the same or similar types of data as targets. Putting an edge eij between drug di and target tj signifies that the drug interacts with that target protein, and seen over the whole set of possible drug–target interactions, this produces a bipartite graph, i.e. a graph where edges are only allowed to pass between one class of nodes (drugs) and the other (targets). Therefore, unlike the local model approach of Bleakley et al. (2007), there is potentially heterogeneity in the types of data representing nodes of the same graph, reflecting the fact that they are either drugs or targets, meaning that the previous approach does not immediately follow over.

3.2 Bipartite graph inference with local models

We propose to solve the bipartite graph inference problem by training several local models to predict new edges linking drug nodes in Vd with target nodes in Vt. More precisely, we predict presence or absence of edge eij between drug di and target tj in the following way.

Excluding target tj, we make a list of all other known targets of di in the bipartite network, as well as a separate list of the targets not known to be targeted by di. The known targets are given a label +1 and the others a label −1.

We look for a classification rule that tries to discriminate the +1-labeled data from the −1-labeled data using the available genomic sequence data for the targets.

We take this rule and use it to predict the label of tj and hence an edge or non-edge between di and tj.

We fix the same target tj, then, excluding drug di, we make a list of all other known drugs targeting tj in the bipartite network, as well as a list of drugs not known to target tj. Similar to before, drugs known to target tj are given the label +1 and the others the label −1.

We look for a classification rule that tries to discriminate the +1-labeled data from the −1-labeled data, using the available chemical structure data for the drugs.

We take this rule and use it to predict the label of di and hence an edge or non-edge between di and tj.

Part of the originality of the present approach is the steps 4–6, where the goal is to make a second independent prediction of the same edge, whenever possible. Even though we are attempting to predict exactly the same edge in both cases, we are doing it with a different dataset in each case and potentially a different classification rule (or class of rules). This gives us two independent predictions for the same edge, though with one caveat. In practice, either the drug may have no known targets or the target may have no known targeting drug. Results in this article are therefore presented to give a clear idea of prediction accuracy in each of the following three cases, where for a given putative drug–target interaction:

The drug has no known target and the target has at least one known targeting drug.

The target has no known targeting drug and the drug has at least one known target.

The drug has at least one known target and the target has at least one known targeting drug.

The first two cases reflect the situation where we want to predict unknown interactions involving newly arriving drug–candidate compounds or target–candidate proteins outside of the training dataset. The third case represents a kind of ‘double application’ of the algorithm, treating each edge of the bipartite network as two directed edges pointing in opposite directions. In this case, we end up with two independent predictions for the same edge. Essentially, we then define a function m(·, ·) that aggregates the two (or even more) prediction scores for the same edge into a global score. A simple heuristic used in this article was the choice m(x, y) = max{x, y}, explored further in Section 5.

3.3 SVM and kernels

In this article, following Bleakley et al. (2007) and Mordelet and Vert (2008), we further investigate the use of SVMs as local classifiers. These are known to provide state-of-the-art performance in many applications (Schölkopf and Smola, 2002; Vapnik, 1998), in particular in computational biology (Schölkopf et al., 2004). Given biological data about the vertices (either the drugs or the targets), each local SVM learns from the labels of these vertices a real-valued function that can then assign a continuous score to the left-out drug or target. Under the local model framework, this is equivalent to assigning a score to the left-out edge. Although the {−1, +1} prediction is usually obtained by simply taking the sign of this score, the value of the score itself contains some form of confidence in the prediction. We propose to rank all candidate edges by the value of their SVM prediction. In cases where we have two scores for candidate edges, we can if we desire first choose a rule to convert these two scores into one score, then rank these aggregated scores.

A further advantage of SVMs is that they can handle vectorial as well as non-vectorial data to represent biological data by the use of the so-called kernel trick (Vapnik, 1998). This means that instead of encoding the biological information about a drug or target v as a vector Xv, an SVM only needs the definition of a positive semi-definite kernel K(u, v) between any two vertices derived from biological information. Many particular kernels for biological data have been developed for various applications in recent years (Schölkopf et al., 2004), and our approach can therefore fully take advantage of these results to learn the structure of local networks around vertices from varied biological data.

3.4 Comparison methods

In order to focus on the differences between the method proposed in this article and the best results we know of by other methods on the given benchmark datasets, we provide a detailed comparison with the kernel regression-based method (KRM) (Yamanishi et al., 2008). We note that this method gave slightly better results than the two methods in Yamanishi (2009) (unpublished data). We also provide a comparison with the baseline method of a nearest neighbor (NN) algorithm. We now briefly recall these methods.

KRM: first, drugs and target proteins on the partially known interaction network are embedded into a unified Euclidean space called the ‘pharmacological space’. Second, a regression model is learned between the chemical structure (respectively, genomic sequence) similarity space and the pharmacological space with respect to drugs (respectively, target proteins). Third, new potential drugs (respectively, target proteins) are mapped into the pharmacological space. Finally, predicted interacting drug and target protein pairs are those which are closer to each other than a given threshold in the pharmacological space.

NN: given a test drug candidate compound, we find a known drug (in the training set) sharing the highest structure similarity with the new compound, and predict the new compound to interact with target proteins known to interact with the nearest drug. Likewise, given a new target candidate protein, we find a known target protein (in the training set) sharing the highest sequence similarity with the new protein, and predict the new protein to interact with drugs known to interact with the nearest target protein. Newly predicted compound–protein interaction pairs are assigned prediction scores with the highest structure or sequence similarity values involving new compounds or new proteins in order to draw receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and PR curves. For more details, see Section 3.1 of Yamanishi et al. (2008).

3.5 Experimental protocol

In order to compare performance of the methods, we performed systematic experiments simulating the process of bipartite network inference from biological data on four drug–target interaction networks. Each experiment represented a full leave-one-out cross-validation experiment, where one known edge (or non-edge) is left out and we try to recover its true label using only the knowledge of the data we have on the drugs and on the targets, including all other known edges between drugs and targets. In order to test the robustness of the new method and further quantify experimental improvements found, we also performed 10 trials of 10-fold cross-validation of all experiments. The 10-fold results can be found in Tables 1–4 in the Supplementary Material and also on the web site (http://cbio.ensmp.fr/~yyamanishi/bipartitelocal/).

Table 1.

Prediction performance for the enzyme dataset

| Method | AUC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| KRMd | 82.8* | 38.7 |

| BLMd | 83.1 | 40.6 |

| m(KRMd,BLMd) | 86.9 | 39.4 |

| KRMt | 92.9* | 80.6 |

| BLMt | 94.2 | 82.3 |

| m(KRMt,BLMt) | 94.4 | 80.7 |

| m(KRMd,KRMt) | 96.7 | 83.1 |

| m(BLMd,BLMt) | 97.3 | 84.1*** |

| m(KRMd,KRMt,BLMd,BLMt) | 97.6** | 83.3 |

| NNd | 68.2 | 33.5 |

| NNt | 89.9 | 76.9 |

| m(NNd,NNt) | 93.0 | 63.8 |

Table 2.

Prediction performance for the ion channel dataset

| Method | AUC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| KRMd | 74.5* | 33.7 |

| BLMd | 74.5 | 33.0 |

| m(KRMd,BLMd) | 73.9 | 33.9 |

| KRMt | 91.7* | 79.6 |

| BLMt | 93.5 | 80.9 |

| m(KRMt,BLMt) | 93.5 | 81.3*** |

| m(KRMd,KRMt) | 96.9 | 77.8 |

| m(BLMd,BLMt) | 97.0 | 77.9 |

| m(KRMd,KRMt,BLMd,BLMt) | 97.3** | 78.1 |

| NNd | 64.7 | 22.9 |

| NNt | 88.7 | 72.8 |

| m(NNd,NNt) | 91.7 | 53.8 |

Table 3.

Prediction performance for the GPCR dataset

| Method | AUC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| KRMd | 87.3* | 40.5 |

| BLMd | 82.3 | 38.8 |

| m(KRMd,BLMd) | 88.2 | 41.4 |

| KRMt | 82.8* | 57.7 |

| BLMt | 87.2 | 56.9 |

| m(KRMt,BLMt) | 86.7 | 57.4 |

| m(KRMd,KRMt) | 94.7 | 66.4 |

| m(BLMd,BLMt) | 95.3 | 66.7*** |

| m(KRMd,KRMt,BLMd,BLMt) | 95.5** | 66.7*** |

| NNd | 69.5 | 32.5 |

| NNt | 81.2 | 52.1 |

| m(NNd,NNt) | 88.5 | 48.5 |

Table 4.

Prediction performance for the nuclear receptor dataset

| Method | AUC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| KRMd | 83.6* | 43.6 |

| BLMd | 81.2 | 41.3 |

| m(KRMd,BLMd) | 85.4 | 45.0 |

| KRMt | 52.3* | 36.2 |

| BLMt | 53.6 | 35.8 |

| m(KRMt,BLMt) | 53.6 | 36.0 |

| m(KRMd,KRMt) | 86.7 | 61.0 |

| m(BLMd,BLMt) | 85.8 | 60.0 |

| m(KRMd,KRMt,BLMd,BLMt) | 88.1** | 61.2*** |

| NNd | 73.3 | 40.5 |

| NNt | 68.7 | 42.3 |

| m(NNd,NNt) | 85.1 | 53.6 |

In order to apply SVM-based methods using kernels, we normally require positive semi-definite kernel functions Kd and Kt that calculate pairwise similarities between any pair of drugs and between any pair of targets. However, for practical applications, in reality all that we need are positive semi-definite matrices of pairwise similarities Kd and Kt for sets of given drugs and targets. The chemical and genomic similarity matrices Sc and Sg were not all positive semi-definite, so those that were not were made so by symmetrizing (adding the transpose and dividing by 2), then adding a small multiple of the identity matrix to their diagonal until all eigenvalues became non-negative. These turned out to be very minor modifications to the original Sc and Sg. We used the LIBSVM (v.2.88) SVM implementation (Chang and Lin, 2001) freely available for the MATLAB environment and the R package (R Development Core Team, 2008) for other data analysis not requiring SVM software. In applying the SVM algorithm to our data, we did not use balanced penalization in the case of positive and negative training sets of different sizes. In all experiments, we fixed the C regularization parameter at 1.

The quality of the ranking was assessed using two criteria. First, as in previous studies, we computed the ROC curve of true positives as a function of false positives when the threshold to predict interactions from the ranking varies. The AUC is used to summarize the ROC curve. Although widely used in classification, the AUC criterion is not always relevant for practical biological applications because there are often magnitudes of order more negative than positive examples. What matters in practice is that, among the best ranked predictions that could potentially be experimentally tested, a sufficient quantity of true positives is present. One way to quantify this is to look at the PR curve, that is, the plot of the ratio of true positives among all positive predictions for each given recall rate. The area under this curve provides a quantitative assessment of how well, on average, predicted scores of positive examples are separated from predicted scores of negative examples. The closer the area under this curve (AUPR for area under PR) is to 1, the better we consider the method to be. In particular, PR curves have greater biological significance than ROC curves for situations where there are very few positive examples as they punish much more the existence of false positive examples found among the best ranked prediction scores.

We refer back to Section 3.2 for a description of BLMs. These, in conjunction with the SVM algorithm provided two independent real-valued prediction scores for each putative drug–target interaction which could be combined to give a global score in various ways (see Sections 4 and 5). These scores were then ranked from smallest to largest and compared with their true (more correctly, ‘known’) label, i.e. edge or not-known edge. The method given in Yamanishi et al. (2008) was tested under the same leave-one-out scheme in order to give directly comparable results.

4 RESULTS

Tables 1–4 give comprehensive results for each of the four benchmark datasets; KRM (Yamanishi et al., 2008), BLMs and NN. m is a given function that accepts several predictions for the same edge and outputs an aggregated prediction. Here, m outputs the largest score from the set of input scores, though other choices are possible. Each table is divided into four parts:

The first gives AUC and AUPR when performing leave-one-out on potential drugs (d).

The second gives results when performing leave-one-out on potential target proteins (t).

The third gives results when combining two or four leave-one-out predictions for the same edge.

The fourth gives results using the NN algorithm and leave-one-out on potential drugs (d), potential target proteins (t) and the result obtained when combining the two.

In each table, (*) indicates the original AUC results for the KRM method (Yamanishi et al., 2008); (**) the best AUC results for methods introduced in this article and (***) the best AUPR result across all methods.

We also performed 10 trials of 10-fold cross-validation of all experimental conditions. These results (with SDs) giving some idea of the robustness of the algorithm, are shown in Tables 1–4 of the Supplementary Material and also on the web site (http://cbio.ensmp.fr/~yyamanishi/bipartitelocal/) and are in general accordance with the results we present here for leave-one-out experiments. These leave-one-out results are separately evaluated based on the three experimental conditions described in Section 3.

4.1 The drug has no known target and the target has at least one known targeting drug

This corresponds to rows 1–3 and 10 in Tables 1–4 and refers to the case where we have a new molecule to screen against the known drug–target bipartite graph. We see that in seven of the eight experimental conditions (dataset ∈{1,2,3,4} × {AUC, AUPR}), the best result comes from the BLMs method or the aggregation of the scores of the two methods via the function m(KRMd,BLMd) = max{KRMd,BLMd}.

4.2 The target has no known targeting drug and the drug has at least one known target

This corresponds to rows 4–6 and 11 in Tables 1–4 and refers to the case where we have a potential target protein (with no known targeting drugs) to screen against the known drug–target bipartite graph. Here, in six of the eight experimental conditions, the best result comes from the BLM method or the aggregation of the scores of the two methods via the function m.

4.3 The drug has at least one known target and the target has at least one known targeting drug

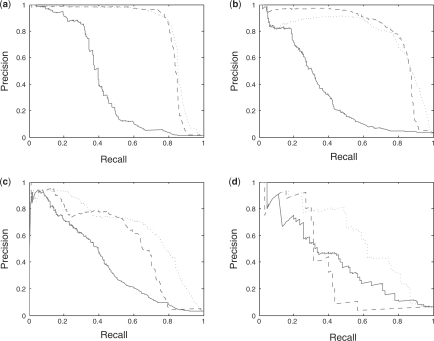

This corresponds to rows 7–9 and 12 in Tables 1–4 and simulates the prediction of missing drug–target interactions in the known bipartite network. Here, we see the significant improvement in AUC and AUPR scores that can be achieved by aggregating the set of prediction scores for the same drug–target interaction (edge) into a global prediction score, also illustrated in the PR curves of Figure 1. We see that in all cases, aggregating scores across the BLM method or across the two methods gives the best AUC and AUPR scores. It is important to note that the idea to aggregate scores via a function m was not used in Yamanishi et al. (2008), so the aggregated results shown in Tables 1–4 for their method, seen alone, are actually an improvement on the results shown in their original article.

Fig. 1.

PR curves for predicted drug–target interactions using BLMs on four benchmark datasets: (a) enzyme, (b) ion channel, (c) GPCR and (d) nuclear receptor. The solid line is for leave-one-out on potential drugs (row 2 of Tables 1–4), the dashed line for leave-one-out on potential target proteins (row 5 of Tables 1–4) and the dotted line for aggregating the two scores for each putative drug–target interaction (row 8 of Tables 1–4). In the benchmark experiments (a), (c) and (d), the aggregated curve mimics or gives a significant improvement over the other two curves. For ion channels (b), leave-one-out on potential target proteins (dashed line) perform slightly better overall than aggregation (dotted line), but both curves represent extremely strong results.

4.4 Global evaluation

The main result is this: the best AUC score for methods introduced in this article is significantly larger than the best score found directly using the kernel regression method for the four benchmark data sets, passing respectively from 92.9 to 97.6, 91.7 to 97.3, 87.3 to 95.5 and 83.6 to 88.1 for the enzyme, ion channel, GPCR and nuclear receptor data sets. Additionally, the best AUPR scores, more biologically relevant, also improve across all 4 benchmark data sets, passing respectively from 80.6 to 84.1, 79.6 to 81.3, 57.7 to 66.7 and 43.6 to 61.2 for the enzyme, ion channel, GPCR and nuclear receptor data sets.

4.5 New predictions

We focus here on the third experimental condition: prediction of missing drug–target interactions in the known bipartite graph, as these results are those which gave a significant improvement with respect to Yamanishi et al. (2008). Essentially, left-out edges that obtain a high positive prediction score, but which are not known to be drug–target interactions, are ideal candidates. We calculated the 20 highest scoring drug–target pairs that were not known to be drug–target interactions at the time of writing of Yamanishi et al. (2008) for each of the four datasets. All predictions along with high-resolution images of the predicted networks for each of the four datasets can be found in the Supplementary Material and also on the web site (http://cbio.ensmp.fr/~yyamanishi/bipartitelocal/). Because of space limitations, we focus here on the results for nuclear receptors.

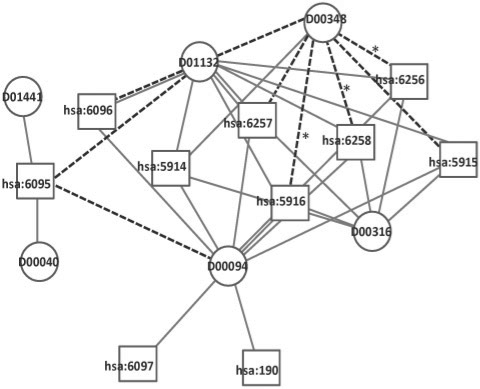

Figure 2 shows part of the predicted network for nuclear receptor data, where edges from the set of the top 20 scoring predictions are shown as dashed lines. These predicted edges enabled us to suggest potentially new drug–target relationships. Table 5 shows the list of the top 10 (of 20) predicted compound–protein pairs, with biological annotation as given in the KEGG database (Kanehisa et al., 2006).

Fig. 2.

Part of the predicted interaction network for the nuclear receptor data. Circles indicate drugs and squares target proteins. Solid edges represent known interactions and dashed ones show some of the 20 highest scoring predicted interactions. Dashed edges with asterisks represent compound–protein interactions now annotated in the SuperTarget database or confirmed in the literature.

Table 5.

Top 10 scoring predicted compound–protein pairs for the nuclear receptor data

| Rank | Pair | Annotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | D00094 | Tretinoin (JAN/USP/INN) |

| 6095 | RORA; RAR-related orphan receptor A | |

| 2 | D00182 | Norethisterone (JP15/INN) |

| 2099 | ESR1; estrogen receptor 1 | |

| 3 | D00348 | Isotretinoin (USP) |

| 5915 | RARB; retinoic acid receptor, beta | |

| 4 | D00348 | Isotretinoin (USP) |

| 5916 | RARG; retinoic acid receptor, gamma | |

| 5 | D00348 | Isotretinoin (USP) |

| 6256 | RXRA; retinoid X receptor, alpha | |

| 6 | D00348 | Isotretinoin (USP) |

| 6257 | RXRB; retinoid X receptor, beta | |

| 7 | D00348 | Isotretinoin (USP) |

| 6258 | RXRG; retinoid X receptor, gamma | |

| 8 | D00094 | Tretinoin (JAN/USP/INN) |

| 3174 | HNF4G; hepatocyte nuclear factor 4, gamma | |

| 9 | D00690 | Mometasone furoate (JAN/USP) |

| 2908 | NR3C1; nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1 | |

| 10 | D00075 | Testosterone (JAN/USP) |

| 5241 | PGR; progesterone receptor | |

Pairs in bold are now annotated in the SuperTarget database or confirmed in the literature.

We used the latest version of the SuperTarget database (Gunther et al., 2008) as of January 2009 to look for evidence supporting our approach. Out of our top 10 predictions, three on the list are now in fact annotated as interacting drug–target pairs: the drug Isotretinoin (D00348) is linked to the protein RARG (hsa:5916) and to RXRA (hsa:6256), and the drug Mometasone furoate (D00690) is linked to the protein NR3C1 (hsa:2908). We did not find the predicted drug–target interaction between Isotretinoin (D00348) and RARB (hsa:5915) in SuperTarget. However, Lotan et al. (1995) show that RARB is selectively lost in premalignant oral lesions and can be restored by treatment with isotretinoin.

To put this result into perspective, we started with a set of 90 known drug–target interactions and 1314 drug–target pairs not known to interact. Of these 1314, we selected only 20 as the most likely to be interacting drug–target pairs, and found that at least 4 of the top 10 of them are experimentally verified drug–target interactions. We take this as strong evidence supporting the practical relevance of our approach.

5 DISCUSSION

In this article, we proposed new statistical methods to predict unknown drug–target interactions from chemical structure information and genomic sequence information simultaneously and on a large scale. The originality of the proposed method lies in the formalization of bipartite graph inference as a set of independent local supervised learning problems, each of which predicts which new drug candidate compounds (respectively, new target candidate proteins) are connected to each target protein (respectively, each compound) in the training set. The results we obtained when predicting human drug–target interaction networks involving enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs and nuclear receptors demonstrated the strength of our proposed method for real drug–target prediction problems, with AUC scores of >97% in some cases and AUPR scores of up to 84%. Figure 1 indicates that in general, the information obtained from the amino acid sequence alignments is more predictive than that obtained from the chemical structure information, suggesting that one way to improve results would be to improve the similarity measure between chemical compounds. Recently added drug–target interactions to the SuperTarget database (Gunther et al., 2008) and a literature search immediately allowed us to confirm at least 4 of the 10 most strongly predicted drug–target interactions for the nuclear receptor dataset obtained using our method.

Various other computational methods have been developed to analyze drug–target or compound–protein interactions. A powerful method is docking simulation (Cheng et al., 2007; Rarey et al., 1996), but this requires 3D structure information for target proteins. Most pharmaceutically useful target proteins are membrane proteins such as ion channels and GPCRs. Determining the 3D structures of membrane proteins is still quite difficult, which limits the use of docking. For example, there are only two GPCRs with 3D structure information (bovine rhodopsin and human β2-adrenergic receptor) at the time of writing. In the same vein, Campillos et al. (2008) require side-effect information of the chemical compounds, which is only well characterized for known drugs. Our method does not need 3D structure information or side-effect information, it only requires chemical structure information of compounds and sequence data of proteins. Thus, an advantage of the method presented here is that it is suitable for simultaneously screening huge numbers of drug–candidate compounds and target candidate proteins.

In the present article, we suggested aggregating scores using the function m(a, b) = max{a, b}. This is a heuristic that appears to work well for extremely ‘unbalanced’ learning problems where there are orders of magnitude more of −1 examples than +1, as is the case here. The vast number of −1 examples has the effect of pulling all predicted scores closer to −1. Therefore, by taking m as the max function, we are saying that we give a potential edge a high aggregated score even if only one of its initial scores escapes the pull of −1. It remains an open question as to whether there is some ‘optimal’ way to select a function m. In particular, Table 2 shows that choosing m(a, b) = max{a, b} is perhaps not always a good idea, especially if one of the two prediction scores for each edge is systematically of low quality.

Lastly, the method we have proposed belongs to a large general class of kernel methods (Schölkopf et al., 2004), so we know that its performance can be potentially improved by using more sophisticated or biologically relevant kernel similarity functions designed for genomic sequences (Saigo et al., 2004) and chemical structures (Mahe et al., 2006).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jean-Philippe Vert and Martial Hue for useful discussions.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bleakley K, et al. Supervised reconstruction of biological networks with local models. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i57–i65. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campillos M, et al. Drug target identification using side-effect similarity. Science. 2008;321:263–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1158140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-C, Lin C-J. LIBSVM: a Library for Support Vector Machines. 2001 Available at http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/∼cjlin/libsvm. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, et al. Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson C. Chemical space and biology. Nature. 2004;432:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature03192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther S, et al. Supertarget and matador: resources for exploring drug-target relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D919–D922. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggarty S, et al. Multidimensional chemical genetic analysis of diversity-oriented synthesis-derived deacetylase inhibitors using cell-based assays. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, et al. Development of a chemical structure comparison method for integrated analysis of chemical and genomic information in the metabolic pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11853–11865. doi: 10.1021/ja036030u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob L, Vert J-P. Protein-ligand interaction prediction: an improved chemogenomics approach. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2149–2156. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser M, et al. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nbt1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla F, et al. Dissecting glucose signalling with diversity-oriented synthesis and small-molecule microarrays. Nature. 2002;416:653–657. doi: 10.1038/416653a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotan R, et al. Suppression of retinoic acid receptor-β in premalignant oral lesions and its up-regulation by isotretinoin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1405–1410. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahe P, et al. The pharmacophore kernel for virtual screening with support vector machines. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006;46:2003–2014. doi: 10.1021/ci060138m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordelet F, Vert J-P. SIRENE: supervised inference of regulatory networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i76–i82. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine N, Sakakibara Y. Statistical prediction of proteinĐchemical interactions based on chemical structure and mass spectrometry data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2004–2012. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rarey M, et al. A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;261:470–489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigo H, et al. Protein homology detection using string alignment kernels. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1682–1689. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf B, Smola AJ. Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf B, et al. Kernel Methods in Computational Biology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg I, et al. BRENDA, the enzyme database: updates and major new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D431–D433. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Waterman M. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell BR. Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000;1:116–125. doi: 10.1038/35038557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik VN. Statistical Learning Theory. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D173–D180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D, et al. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D901–D906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi Y. Supervised bipartite graph inference. In: Koller D, et al., editors. Proceedings of the Conference on Advances in Neural Information and Processing System 21. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 1433–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi Y, et al. Prediction of drug-target interaction networks from the integration of chemical and genomic spaces. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i232–i240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]