Abstract

The mammalian circadian clockwork is modelled as transcriptional and post-translational feedback loops, whereby circadian genes are periodically suppressed by their protein products. We show that adenosine 3′5′ monophosphate (cAMP) signalling constitutes an additional, bona fide component of the oscillatory network. cAMP signalling is rhythmic and sustains the transcriptional loop of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, determining canonical pacemaker properties of amplitude, phase and period. This role is general, being evident in peripheral mammalian tissues and cell lines, thus revealing an unanticipated point of circadian regulation in mammals qualitatively different from the existing transcriptional feedback model. We propose that daily activation of cAMP signalling, driven by the transcriptional oscillator, in turn sustains progression of transcriptional rhythms. In this way, clock output constitutes an input to subsequent cycles.

Report

The suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus are the principal circadian pacemaker in mammals, driving the sleep-wake cycle and co-ordinating subordinate clocks in other tissues(1). Disturbed circadian timing can have a major negative impact on human health(2). The molecular clockwork within the SCN has been modelled as a combination of transcriptional and post-translational negative feedback loops(3), whereby protein products of Period and Cryptochrome genes periodically suppress their own expression(4). It is unclear how long-term, high amplitude oscillations with a daily period are maintained, not least because transcriptional feedback loops are typically less precise than the oscillation of the circadian clock and oscillate at a higher frequency than one cycle per day(5). Moreover, recombinant cyanobacterial proteins can sustain circadian cycles of auto-phosphorylation in vitro, in the absence of transcription(6) and intracellular signalling molecules cADPR and Ca2+ are essential regulators of circadian oscillation in Arabidopsis and Drosophila(7, 8), indicating that transcriptional mechanisms may not be the sole, nor principal, arbiter of circadian pacemaking(9, 10). We show that the transcriptional feedback loops of the SCN are sustained by cytoplasmic adenosine 3′5′ monophosphate (cAMP) signalling, which determines their canonical properties of amplitude, phase and period. This extends the concept of the mammalian pacemaker beyond transcriptional feedback to incorporate its integration with rhythmic cAMP-mediated cytoplasmic signalling.

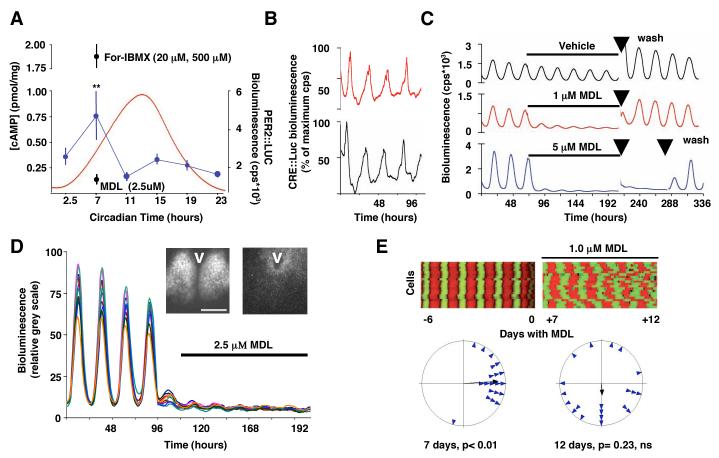

We tracked the molecular oscillations of the SCN as circadian emission of bioluminescence by organotypical slices from transgenic mouse brain. Rhythmic luciferase activity controlled by the Per1 promoter (Per1::luciferase) reported circadian transcription and a fusion protein of mPER2 and LUCIFERASE (mPER2::LUC) reported circadian protein synthesis rhythms. Under these conditions, the cAMP content of the SCN was circadian (Fig. 1A) and accompanied by a circadian cycle in activity of cAMP response element sequences (CRE) reported by a CRE::luciferase adenovirus (Fig. 1B). In molluscs, birds and in the mammalian SCN, cAMP is implicated in entrainment or maintenance of clocks or both(11-13) or mediation of clock output. It has not been considered as part of the core oscillator(14). If the cAMP-mediated rhythm of CRE activity is necessary for SCN pacemaking, its suppression should compromise circadian gene expression. We treated SCN slices with MDL-12,330A (MDL), a potent, irreversible inhibitor of adenylyl cyclase (AC)(15) to reduce concentrations of cAMP to basal levels (Fig. 1A). MDL rapidly suppressed circadian CRE::luciferase activity, presumably through loss of cAMP-dependent activation of CRE sequences (Fig. S1A), and caused a dose-dependent decrease in the amplitude of cycles of circadian transcription and protein synthesis observed with mPer1::luciferase and mPER2::LUC (Fig 1C, S1B, C). Damping was reversible over several days and not an artefact of the bioluminescent reporters because MDL also suppressed mPer1-dependent circadian transcription reported by green fluorescent protein (Fig. S1D). Video imaging of mPER2::LUC expression showed that MDL (2.5 μM) rapidly suppressed cellular circadian gene expression to barely detectable levels (Fig. 1D). Prolonged exposure to MDL (1.0 μM) suppressed and desynchronised the transcriptional cycles of SCN cells (Fig. 1E). Pharmacological inactivation of AC therefore mimicked the effect of pertussis toxin(16) and loss of the gene encoding the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 (Vip2r), an activator of AC within the SCN(17). MDL also reduced cAMP to undetectable levels in NIH 3T3 fibroblast cultures (Fig. S2A, B) and suppressed circadian transcriptional cycling revealed by a Bmal1::luc reporter(3) (Fig. S2C-E). MDL had no effect, however, on luciferase expression from NIH 3T3 cells transfected with a control, non-circadian (CMV) promoter (Fig. S2F).

Fig. 1. Dampened and desynchronised cellular circadian gene expression in SCN after suppression of cAMP and CRE rhythms.

(A) Circadian oscillation of cAMP concentration (blue) and PER2::LUC bioluminescence (red), and cAMP concentration in SCN slices treated with MDL-12,330A (MDL) or with forskolin plus IBMX. **p<0.01 vs. other samples, ANOVA and post-hoc Duncan’s. (B) Circadian oscillation of CRE activity in two representative SCN slices reported by CRE:luciferase adenovirus. (C) Reversible, dose-dependent suppression of SCN PER2::LUC expression by MDL. Arrows indicate medium changes. (D) Effect of MDL on PER2::LUC expression in individual SCN neurons (n= 20), bioluminescence expressed as relative grey scale (0-255 pixel intensity). Videomicrographs illustrate distribution of PER2::LUC expression before (left) and during (right) treatment with MDL, V= 3rd ventricle, bar= 500μm. (E) Desynchronisation of cellular pacemakers of SCN revealed by (above) raster plots and (below) Rayleigh plots of PER2::LUC oscillations of 20 representative SCN neurons before and after addition of MDL. Data representative of 3 or more slices.

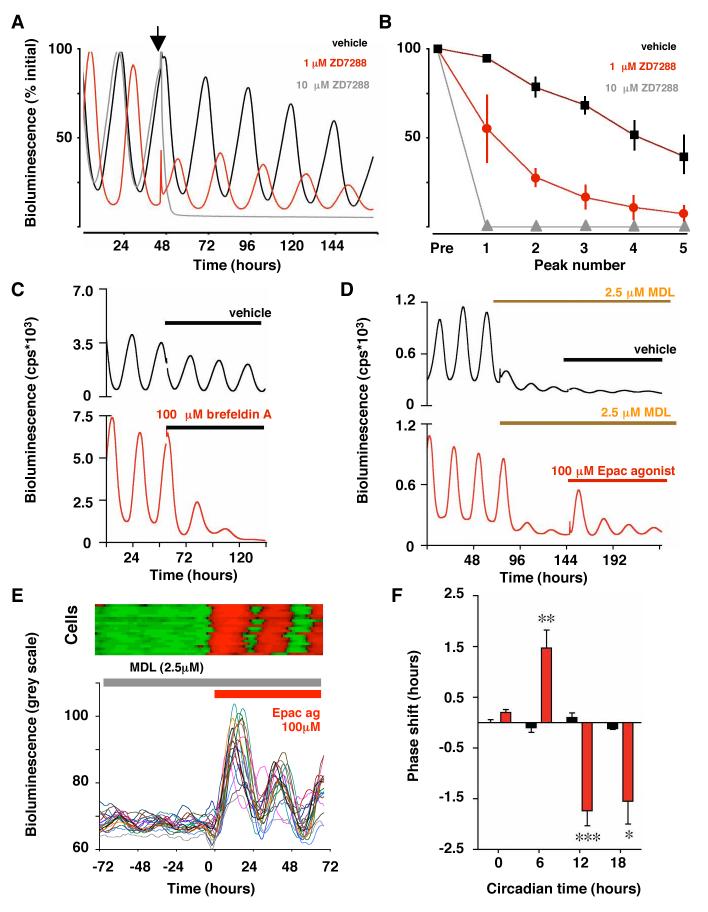

If cAMP sustains the clock, interference with cAMP effectors should compromise pacemaking. Treatment of brain slices with inhibitors of cAMP-dependent protein kinase had no effect, however, on circadian gene expression in the SCN (Fig. S3). cAMP also acts through hyperpolarising cyclic-nucleotide gated ion channels (HCN)(18) and through the guanine nucleotide-exchange factors Epac1 and Epac2(19). The irreversible HCN channel blocker ZD7288, which would be expected to hyperpolarize the neuronal membrane, dose-dependently dampened circadian gene expression in the SCN (Figure 2A, B). This is consistent with disruption of transcriptional feedback rhythms by other manipulations that hyperpolarize clock neurons(17, 20, 21). Brefeldin A applied at a dose that antagonises Epac but does not affect synaptic transmission(22) also rapidly and chronically suppressed SCN pacemaking (Fig. 2C, S4A). Thus, circadian pacemaking is sustained by cAMP effectors as well as AC activity. Direct activation of the effectors might compensate, therefore, for inactivation of AC by MDL. A hydrolysis-resistant Epac agonist (Sp-8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMPS, Fig. 2D, S4B) transiently activated oscillations in transcriptional activity in SCN treated with MDL. An agonist active on both Epac and PKA (Sp-8-CPT-cAMPS) also transiently activated circadian gene expression, whereas an agonist specific for PKA (6-Bnz-cAMP) had no effect (Fig. S4B). Video imaging showed that Epac agonist synchronously activated circadian gene expression in individual SCN cells (Fig. 2E). The transcriptional cycles induced by Epac agonism damped rapidly in the presence of MDL, however, demonstrating that when cAMP concentrations were permanently suppressed, the re-activated transcriptional feedback loops were not self-sustaining.

Fig. 2. Influence of effectors of cAMP signalling on SCN circadian pacemaking.

(A) Effect of HCN channel blocker ZD7288 (arrowhead) on SCN mPER2:LUC circadian gene expression. (B) Damping of peak bioluminescence in SCN slices treated with vehicle or ZD7288 (Pre= pre-treatment, Mean±SEM, n>4). (C) Brefeldin A suppresses circadian gene expression in PER2::LUC SCN. (D) Transient re-activation of MDL-suppressed circadian PER2::LUC expression in SCN slices by Sp-8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMPS. (E) Acute activation of cellular circadian gene expression (expressed as relative grey scale units) by Epac agonist in presence of MDL, illustrated by raster (upper panel) and graphical plots (lower panel) of 20 representative cells. (F) Phase shifts of SCN circadian PER2::LUC bioluminescence rhythm by Epac agonist (Sp-8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, red) but not vehicle (black, mean±SEM, n>3 per time point, ** p<0.01 vs. vehicle, ANOVA and Bonferroni).

Epac can lead to activation of the transcription factor CRE-binding protein (CREB) by phosphorylation(23), and so CRE sequences in Per1 and Per2 are likely points of integration between Epac and the core loop. Epac agonist acutely triggered CREB phosphorylation (Fig. S4C) and CRE::luciferase activity (% increase±S.E.M.: vehicle 1.9±0.7%, Epac agonist 38.4±13.0, n= 4) in SCN slices treated with MDL. If Epac activity were rate-limiting during the normal circadian cycle, acute activation should reset the oscillator, and indeed a short-acting, hydrolysable Epac agonist (Sp-8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) phase-shifted SCN slices (Fig. 2F). As with cAMP agonists(13) treatment of slices with Epac agonist during the circadian day advanced the SCN. The dependence of circadian gene expression on cAMP mediators Epac1 and Epac2 and HCN confirms the necessary contribution of cAMP signalling in sustaining the SCN pacemaker.

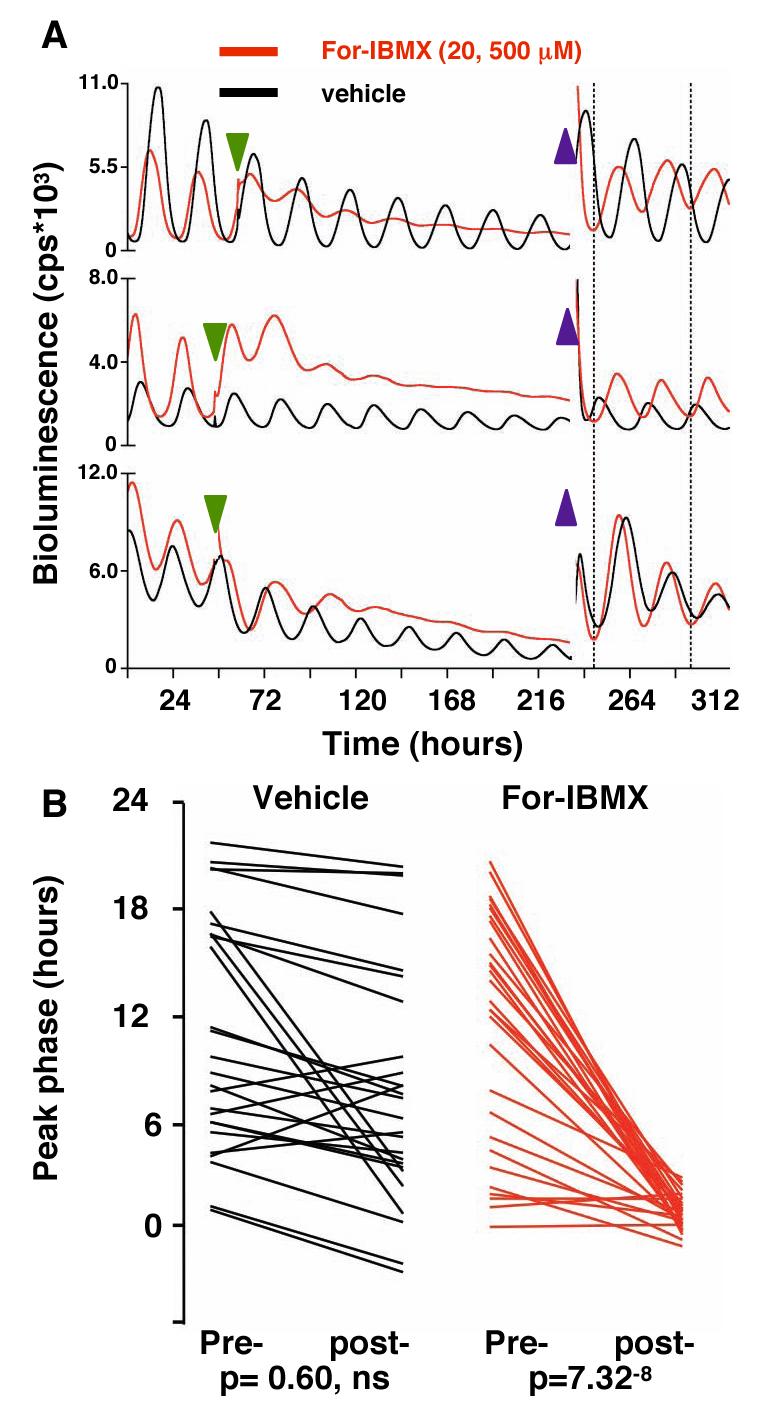

If circadian cAMP signalling is an intrinsic part of the pacemaker, feeding back into the transcriptional loops rather than just being an output, it should determine their temporally specific parameters of phase and period. To test this, we de-coupled cAMP concentrations from the transcriptional oscillator by treating SCN slices with forskolin (For), the activator of AC, and the cAMP phosphodiestease inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxhantine (IBMX). This chronically elevated cAMP levels (Fig. 1A) and acutely increased mPER2::LUC activity (Fig. 3A). Previously asynchronous SCN slices were re-synchronised: an effect inconsistent with cAMP signalling acting solely as an output (Fig. S5A). Continued exposure of slices to For-IBMX elevated the circadian nadir of mPER2::LUC expression, damping amplitude and definition of the circadian profile of the slice and of individual cells across the SCN (Fig. 3A, S5B, C). With sustained elevation of cAMP concentrations the imposed synchrony between free-running slices dissipated (Fig. S5D).

Fig. 3. Alterations in the phase of the SCN oscillator after acute transitions in cAMP concentrations.

(A) PER2::LUC bioluminescence rhythms from SCN treated with vehicle or forskolin and IBMX (green arrowhead), followed by washout (blue arrowheads). Dotted lines highlight synchrony of For-IBMX-treated slices, but not control slices, after washout. (B) Phases of PER2::LUC rhythms in individual SCN immediately before (pre-) and four days after (post-) washout of vehicle or For/IBMX. Removal of For-IBMX caused resynchronisation, driving slices to a common phase regardless of phase before washout.

After 5-7 days of treatment with For-IBMX, we acutely reduced cAMP concentrations by transferring slices to fresh medium. This was done as a “wedge” experiment(24, 25), such that the reduction of cAMP concentrations was imposed at different phases of the ongoing oscillations of different slices. If cAMP signals constitute part of the pacemaker and not solely its output, the enforced decline in cAMP concentrations would set the transcriptional oscillator to a new unique phase. Consequently the gene expression rhythms of all slices would be synchronised, regardless of their phase before washout. Washout did not synchronise vehicle-treated SCN (Fig. 3B, S5D). In contrast, washout re-synchronised SCN previously treated with For-IBMX to a common phase distinct from that of control slices. Importantly, the phase of peak PER2::LUC activity occurred ca. 39±11 minutes after washout, which is consistent with the ca. 1 hour delay between the circadian minimum of cAMP content and peak PER2::LUC activity in free-running SCN slices (Fig. 1A). Hence, the behaviour of the transcriptional loop was determined by acute changes in cAMP signalling, de-coupled pharmacologically from that loop. As with protein synthesis(25), these results identify cAMP as a component of the SCN oscillator.

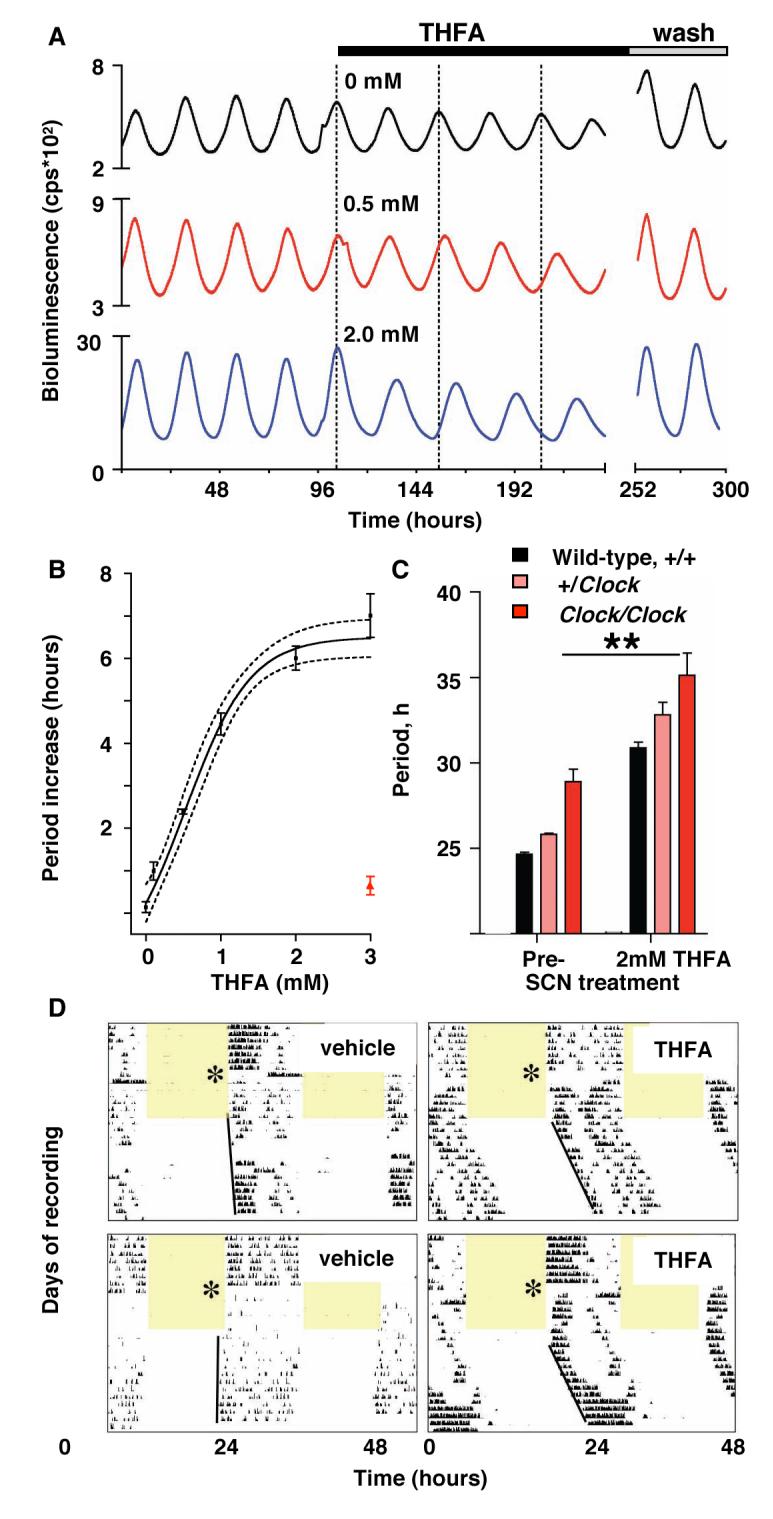

Finally, if cAMP signalling is an integral component of the SCN pacemaker, altering the rate of cAMP synthesis should affect circadian period. 9-(tetrahydro-2-furyl)-adenine (THFA) is a non-competitive AC inhibitor (15) which slows the rate of Gsα–stimulated cAMP synthesis, thereby attenuating peak concentrations (Fig. S2A, B). THFA dose-dependently increased the period of circadian pacemaking in the SCN, from 24 to 31 hours (Fig. 4A, B) with rapid reversal upon washout. Rhythm amplitude decreased at higher concentrations of THFA (Fig. S6A). Imaging of individual cells revealed that THFA increased period in neurons across the SCN (Fig. S6B). Other non-competitive inhibitors also lengthened SCN period (Fig. S6C). The effect of THFA was additive to that of the Clock mutation (Fig. 4C), suggesting THFA acts in addition to, and independently of, E-box mediated trans-activation by CLOCK and BMAL1. Further, THFA acted additively with inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), generating unusually long periods of 36 hours (Fig. S6D, E). THFA also lengthened period of circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from mPER2::LUC mice and fibroblasts transfected with Bmal1::luc reporter (Fig. S7A-D). Importantly, THFA lengthened circadian period of wheel-running when delivered continuously, directly to the SCN of mice via intra-cerebral cannulae (Fig. 4D, S7E). The differential circadian effects of AC inhibitors: damping vs. period lengthening by MDL and THFA respectively, reflect their particular actions on cAMP kinetics. The current results therefore suggest that non-competitive inhibitors such as THFA might be of therapeutic value in patients with acute (jet-lag, shiftwork) or maintained (Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome(26)) acceleration of circadian period.

Fig. 4. Prolonged SCN circadian period in vitro and in vivo after inhibition of AC by THFA.

(A) Effect of THFA on circadian period of representative SCN slices, reported by mPer1::luciferase (B) Sigmoidal curve fit to one-site inhibition model with 95% confidence limits. Red data point indicates period after washout. (C) Circadian period in SCN from wild-type and Clock mutant mice, before or during treatment with THFA (**p<0.01 vs. pre-treatment, ANOVA and Bonferroni test). All data plotted as mean±SEM, n≥3. (D) Representative double-plotted, wheel-running records of mice treated with (left) vehicle- and (right) THFA (delivered to SCN via osmotic mini-pump). Mice entrained to 12 hours light (shaded) and 12 hours dim red light were released into continuous dim-red. Asterisk indicates day of surgery and commencement of infusion.

We conclude that circadian pacemaking in mammals is sustained and its canonical properties of amplitude, phase and period are determined by a reciprocal interplay in which transcriptional and post-translational feedback loops drive rhythms of cAMP signalling, and that dynamic changes in cAMP signalling, in turn, regulate transcriptional cycles. Thus, output from the current cycle constitutes an input into subsequent cycles. The interdependence between nuclear and cytoplasmic oscillator elements we describe for cAMP also occurs in the case of Ca2+ and cADPR (7, 8), thus highlighting an important newly recognized common logic to circadian pacemaking in widely divergent taxa.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Butcher for technical support, S.R. Williams, C.P.Kyriacou and G. Churchill for discussion, H. Okamura (Kyoto, Japan), H. Ueda (RIKEN, Japan) and H. Rehmann (Utrecht, The Netherlands) for reagents. Funded by Medical Research Council and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK.

Footnotes

The Authors have no competing financial interests.

Summary sentence: Cytosolic cAMP signalling integrates with, sustains and determines the rhythmic properties of the transcriptional feedback loops of the mammalian circadian clock.

Supporting Online Material. ??www.sciencemag.Tbc Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S7 References.

References

- 1.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Nature. 2002 Aug 29;418:935. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003 Aug;4:649. doi: 10.1038/nrn1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueda HR, et al. Nat Genet. 2005 Feb;37:187. doi: 10.1038/ng1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato TK, et al. Nat Genet. 2006 Mar;38:312. doi: 10.1038/ng1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirata H, et al. Science. 2002 Oct 25;298:840. doi: 10.1126/science.1074560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima M, et al. Science. 2005 Apr 15;308:414. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd AN, et al. Science. 2007 Dec 14;318:1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1146757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrisingh MC, Wu Y, Lnenicka GA, Nitabach MN. J Neurosci. 2007 Nov 14;27:12489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3680-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakin-Thomas PL. J Biol Rhythms. 2006 Apr;21:83. doi: 10.1177/0748730405286102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Y, Hida A, Anderson DA, Izumo M, Johnson CH. Curr Biol. 2007 Jul 3;17:1091. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskin A, Takahashi JS, Zatz M, Block GD. J Neurosci. 1984 Oct;4:2466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-10-02466.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi JS, Zatz M. Science. 1982;217:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.6287576. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prosser RA, Gillette MU. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9(3):1073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-03-01073.1989. 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zatz M, Mullen DA. Brain Res. 1988 Jun 21;453:51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippe C, Ardizzone C. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1991;99:209. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(91)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aton SJ, Huettner JE, Straume M, Herzog ED. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Dec 12;103:19188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607466103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maywood ES, et al. Curr Biol. 2006 Mar 21;16:599. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum T, Gordon SE. Neuron. 2004 Apr 22;42:193. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Rooij J, et al. Nature. 1998 Dec 3;396:474. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitabach MN, Blau J, Holmes TC. Cell. 2002 May 17;109:485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundkvist GB, Kwak Y, Davis EK, Tei H, Block GD. J Neurosci. 2005 Aug 17;25:7682. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CC, Hsu KS. Mol Pharmacol. 2006 Mar;69:846. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi GX, Rehmann H, Andres DA. Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Dec;26:9136. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronson BD, Johnson KA, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Science. 1994 Mar 18;263:1578. doi: 10.1126/science.8128244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi S, et al. Science. 2003 Nov 21;302:1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1089287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y, et al. Nature. 2005 Mar 31;434:640. [Google Scholar]