Abstract

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) catalyzes a rate-limiting step in glycogen and starch synthesis in bacteria and plants, respectively. Plant AGPase consists of two large and two small subunits that were derived by gene duplication. AGPase large subunits have functionally diverged, leading to different kinetic and allosteric properties. Amino acid changes that could account for these differences were identified previously by evolutionary analysis. In this study, these large subunit residues were mapped onto a modeled structure of the maize (Zea mays) endosperm enzyme. Surprisingly, of 29 amino acids identified via evolutionary considerations, 17 were located at subunit interfaces. Fourteen of the 29 amino acids were mutagenized in the maize endosperm large subunit (SHRUNKEN-2 [SH2]), and resulting variants were expressed in Escherichia coli with the maize endosperm small subunit (BT2). Comparisons of the amount of glycogen produced in E. coli, and the kinetic and allosteric properties of the variants with wild-type SH2/BT2, indicate that 11 variants differ from the wild type in enzyme properties or in vivo glycogen level. More interestingly, six of nine residues located at subunit interfaces exhibit altered allosteric properties. These results indicate that the interfaces between the large and small subunits are important for the allosteric properties of AGPase, and changes at these interfaces contribute to AGPase functional specialization. Our results also demonstrate that evolutionary analysis can greatly facilitate enzyme structure-function analyses.

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) catalyzes the conversion of Glc-1-P (G-1-P) and ATP to ADP-Glc and pyrophosphate. This reaction represents a rate-limiting step in starch synthesis (Hannah, 2005). AGPase is an allosteric enzyme whose activity is regulated by small effector molecules. In plants, AGPase is activated by 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde (3-PGA) and deactivated by inorganic phosphate (Pi).

Plant AGPase is a heterotetramer consisting of two identical large and two identical small subunits. The large and small subunits of AGPase were generated by a gene duplication. Subsequent sequence divergence has given rise to complementary rather than interchangeable subunits. Indeed, both subunits are needed for AGPase activity (Hannah and Nelson, 1976, Burger et al., 2003). Biochemical studies have indicated that both subunits are important for catalytic and allosteric properties (Hannah and Nelson, 1976; Greene et al., 1996a, 1996b; Ballicora et al., 1998; Laughlin et al., 1998; Frueauf et al., 2001; Kavakli et al., 2001a, 2001b; Cross et al., 2004, 2005; Hwang et al., 2005, 2006, 2007; Kim et al., 2007; Ventriglia et al., 2008). Surprisingly, Georgelis et al. (2007, 2008) showed that, in angiosperms, the small subunit is under greater evolutionary pressure compared with the large subunit. Detailed analyses have shown that the greater constraint on the small subunit is due to its broader tissue expression patterns compared with the large subunit and the fact that the small subunit must interact with multiple large subunits.

Large subunits have undergone more duplication events than have small subunits (Georgelis et al., 2008). This has led to the creation of five groups of large subunits that differ in their patterns of tissue of expression (Akihiro et al., 2005; Crevillen et al., 2005; Ohdan et al., 2005). Crevillen et al. (2003) studied the biochemical properties of four Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) AGPases consisting of the four different large subunits and the only functional small subunit in Arabidopsis. The different AGPases had different kinetic and allosteric properties. More specifically, the AGPases differed in their affinity for the allosteric regulator 3-PGA and the substrates G-1-P and ATP. This possibly reflects the different 3-PGA, G-1-P, and ATP levels in the various tissues. This evidence indicates that not only did the different large subunit groups subfunctionalize in terms of expression, but also these groups may have specialized in terms of protein function. While the study of Crevillen et al. (2003) pointed to functional specialization of the large subunit, the identity of the amino acid sites in the large subunit that account for these kinetic and allosteric differences was not pursued.

Georgelis et al. (2008) presented supporting evidence for AGPase large subunit specialization by identifying positively selected amino acid sites in the phylogenetic branches following gene duplication events. We also identified amino acid residues that were conserved in one large subunit group but not conserved in another large subunit group (type I functional divergence; Gu, 1999) and amino acid residues that are conserved within large subunit groups but are variable among large subunit groups (type II functional divergence; Gu, 2006). Positively selected type I and type II sites could have contributed to specialization of the different large subunit groups. Indeed, positively selected type II sites in several proteins have been proven via site-directed mutagenesis (Bishop, 2005; Norrgård et al., 2006; Cavatorta et al., 2008; Courville et al., 2008) to be important for protein function and functional specialization. Additionally, several positively selected type I and type II amino acid sites in the large AGPase subunit identified in our previous evolutionary analysis (Georgelis et al., 2008) have been implicated in the kinetic and allosteric properties and heat stability of AGPase. The role of these sites was demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis experiments of large subunits from Arabidopsis, maize endosperm, and potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber (Ballicora et al., 1998, 2005; Kavakli et al., 2001a; Jin et al., 2005; Linebarger et al., 2005; Ventriglia et al., 2008). These analyses indicate that the rest of the amino acid sites identified as positive type I and type II sites in our previous evolutionary analysis (Georgelis et al., 2008) represent promising candidate targets for mutagenesis.

To identify large subunit amino acids that are possibly important in controlling enzyme properties and that may have contributed to large subunit specialization, we conducted site-directed mutagenesis of the maize endosperm large subunit encoded by Shrunken-2 (Sh2). We specifically identified amino acids of SH2 that correspond to amino acid sites that were detected as positive type I and type II sites during the large subunit evolution (Georgelis et al., 2008). We then replaced the SH2 residues with amino acids of a group different from the SH2 family. Several amino acid sites important for the kinetic and allosteric properties and heat stability of AGPase were identified. Our results indicate that the subunit interfaces between the large and small subunits are important for the allosteric properties of AGPase. They also indicate that amino acid changes at subunit interfaces have been important for AGPase specialization in terms of allosteric properties. These experiments also support the idea that the majority of positively selected sites as detected by codon substitution models (Nielsen and Yang, 1998; Yang et al., 2000) and type II sites are not false positives. Site-directed mutagenesis of such sites can greatly facilitate enzyme structure-function analyses.

RESULTS

Previous Phylogenetic Analysis and Structural Mapping of Type II and Positively Selected Sites

AGPase large subunits can be placed into five groups depending on sequence similarity and tissues of expression (Supplemental Fig. S1; Georgelis et al., 2007, 2008). Group 4 includes only two sequences whose role has not been studied. Accordingly, we restricted further evolutionary analysis to the remaining four groups. We identified 21 type II sites (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S1) by doing an analysis of all of the pairwise comparisons between the different large subunit groups shown in Supplemental Figure S1 (Georgelis et al., 2008). These amino acid sites potentially contributed to the functional divergence among AGPase large subunits. Type II sites 96 and 106 were shown to play an important role in enzyme catalysis (Ballicora et al., 2005), while site 506 has been implicated in the allosteric properties of the potato tuber AGPase (Ballicora et al., 1998). We also detected 18 amino acid sites upon which potential positive selection may have taken place in the tree branches following the gene duplications that led to the different large subunit groups (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S1; Georgelis et al., 2008). These sites could also be important in large subunit specialization, since functional diversification among different large subunits could have been beneficial for the fitness of the plant. Positively selected sites 104, 230, 441, and 445 are implicated in the allosteric properties of AGPase (Kavakli et al., 2001a; Ballicora et al., 2005; Jin et al., 2005). Finally, we identified 91 type I sites. These sites are apparently important for AGPase function in one group but not in another group, and they could contribute to subfunctionalization or specialization or both among large subunit groups. The usefulness, however, of type I sites in detecting functional divergence has been disputed (Philippe et al., 2003), since type I divergence between orthologous and paralogous groups is indistinguishable in some instances (Gribaldo et al., 2003). It would be expected that paralogues should exhibit more functional divergence compared with that revealed by orthologues. Therefore, there may be a considerable number of false-positive sites of type I divergence that do not necessarily represent functional divergence.

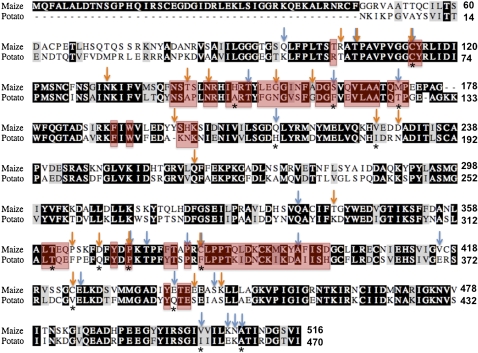

Figure 1.

Amino acid alignment between maize endosperm (SH2) and potato tuber large subunit. Red boxes indicate sites that make direct contact with the small subunit as determined by Tuncel et al. (2008). Blue and orange arrows indicate type II and positively selected sites, respectively. Sites subjected to mutagenesis in this study are marked with asterisks.

The fact that several type II and positively selected sites have already been shown to be important for the kinetic and allosteric properties of AGPase strongly suggests that the remaining type II and positively selected sites may also be important for enzyme function. To gain insight into the potential role of these sites, we placed them on the modeled structure of the SH2 protein. The type I sites were excluded from this initial analysis, since the potential inclusion of a high number of false positives could confound the results.

Although the only plant crystal structure available is a potato tuber small subunit homotetramer (Jin et al., 2005), the high degree of identity (40%–45%) and similarity (55%–65%) between the small and large subunits strongly suggests that the structure of the physiologically relevant AGPase heterotetramer will be very similar or identical to the resolved homotetramer structure. Superimposition of SH2 and maize endosperm small subunit (BT2) on the solved potato structure agrees with this conjecture (Fig. 2). Additionally, the potato tuber AGPase heterotetramer was modeled after the homotetrameric structure, and a molecular dynamics study was conducted to determine the most thermodynamically favorable interactions between the large and small subunits (Fig. 1; Tuncel et al., 2008). Superimposition of the potato tuber large subunit on SH2 indicates that the two structures are virtually identical (Fig. 3). This enables us to use the potato tuber large subunit modeled structure to determine the areas of SH2 that interact with BT2. According to the modeled potato tuber heterotetramer (Tuncel et al., 2008), a SH2 molecule makes direct contacts with one molecule of BT2 through its C-terminal domain (tail-to-tail interaction) and to the second BT2 protein through its N-terminal catalytic domain (head-to-head interaction), as shown in Figure 2. We observed that 17 out of 29 amino acid sites (type II and positively selected) were at or near the subunit interfaces (Fig. 4). The areas of SH2 that participate in subunit interactions do not constitute more than 30% of the SH2 monomer structure. Hence, almost 60% of the residues that were selected through evolutionary analysis were located in less than 30% of the SH2 monomer. This preferential localization of the residues at subunit interfaces points to the possibility that subunit interfaces are important for the functional specialization of the AGPase large subunit.

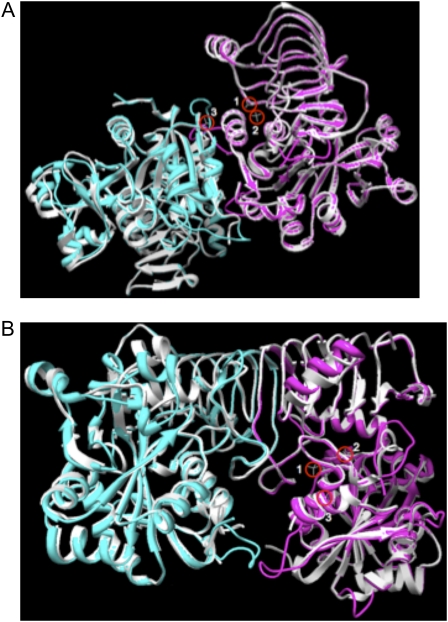

Figure 2.

AGPase subunit interactions. The white structures correspond to the resolved structure of potato tuber small subunit homodimers. Cyan and magenta modeled structures of the small (BT2) and large (SH2) subunits of maize endosperm, respectively, are superimposed on the structure of potato tuber small subunit homodimers. Red circles indicate the candidate Pi-binding sites. A, Head-to-head subunit interaction. B, Tail-to-tail subunit interaction.

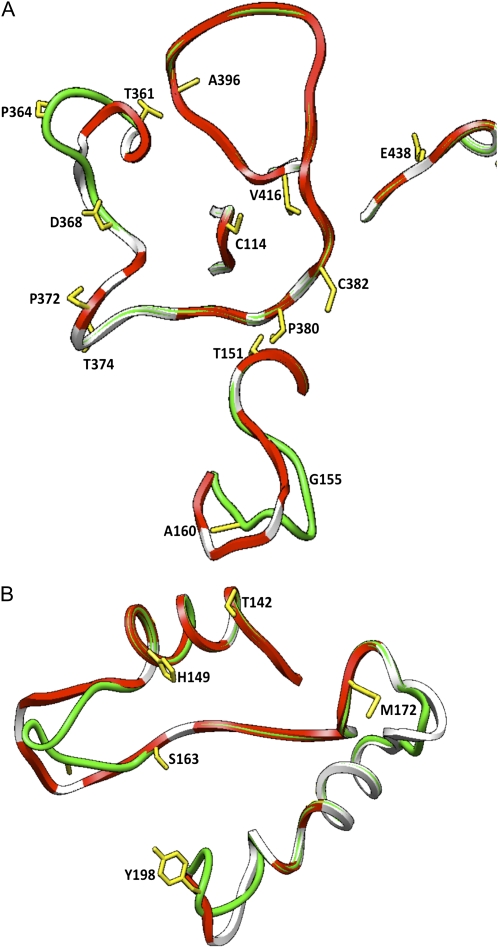

Figure 3.

Superimposition of maize endosperm large subunit (SH2) modeled structure (magenta) on the potato tuber large subunit modeled structure (white). Red areas indicate sites in the potato tuber large subunit that are proposed to make direct contact with the small subunit (Tuncel et al., 2008).

Figure 4.

Placement of all type II and positively selected amino acids on the subunit interfaces of maize endosperm large subunit (SH2). Type I sites 149 and 361 that were changed by site-directed mutagenesis are also placed on the structure of SH2. SH2 modeled structure (green) was superimposed on potato tuber large subunit modeled structure (white). Red areas indicate sites in the potato tuber large subunit that are proposed to make direct contact with the small subunit (Tuncel et al., 2008). Type I, type II, and positively selected sites detected by Georgelis et al. (2008) are shown in yellow. A, Areas that participate in tail-to-tail interactions. B, Areas that participate in head-to-head interactions.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

To determine the role, if any, of type II and positively selected amino acid sites, and particularly the ones found at the subunit interfaces, in AGPase function and to gain insight into their potential roles in large subunit specialization, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on 12 sites in SH2. We mutagenized seven SH2 sites (four type II, one positively selected, and two both type II and positively selected) located at the subunit interfaces and five sites (three type II, two positively selected) located in the rest of the SH2 monomer. In all cases, the residue of SH2, which belongs to group 3b (Supplemental Fig. S1), was changed to a residue found in other groups. To gain more information about the subunit interfaces, we scanned type I sites for the ones that are located in the subunit interfaces. We selected type I site 149 as a target because SH2-containing group 3b contains a His while other groups contain the physicochemically different Ala or Ser. His was changed to a Ser. We also selected type I site 361, which is also located in subunit interfaces. This site is invariant in group 2 but variable in group 3b. Group 3b can be subdivided in two subgroups, one that contains only endosperm-specific large subunits, including SH2, and one that includes mostly embryo large subunits. SH2 along with the other members of the former subgroup contain a Thr at site 361, while the latter subgroup contains a Cys. The Thr of SH2 was changed to a Cys, which has different physicochemical properties.

Glycogen Production

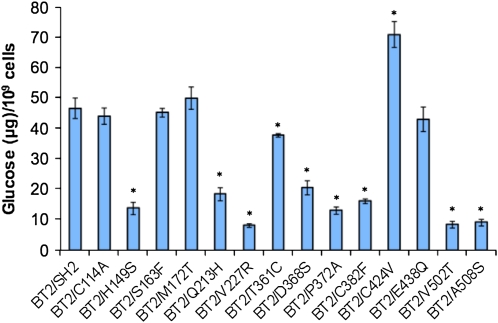

Wild-type SH2 and the 14 SH2 variants created by site-directed mutagenesis were expressed with wild-type BT2 in Escherichia coli strain AC70R1-504 (see “Materials and Methods”), and the resulting glycogen of each genotype was quantified. The majority (10 of 14) of the SH2 variants resulted in altered amounts of glycogen (Fig. 5). This strongly suggests that the majority of the mutations introduced in SH2 were not neutral, at least when expressed in E. coli, despite the fact that the substituted amino acid residues are present in other large subunit groups.

Figure 5.

Glycogen produced by SH2 wild type and variants expressed in E. coli along with BT2. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with wild-type BT2/SH2 at P = 0.05 (Student's t test; n = 4). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Expression of the Sh2 mutants without the presence of the BT2 protein in E. coli resulted in no glycogen production (data not shown), indicating that potential SH2 homotetramers are inactive. It is also known that wild-type SH2 and BT2 homotetramers do not produce any glycogen in E. coli (Georgelis and Hannah, 2008). Hence, the changes in glycogen production of the Sh2 mutants are most likely due to altered properties of the SH2/BT2 heterotetramer.

Characterization of Kinetic and Allosteric Properties of SH2 Variants

Glycogen levels suggested that some of the mutants alter AGPase function at the protein/enzyme level. Therefore, the SH2 variants and wild-type SH2 were expressed in E. coli along with wild-type BT2, and the resulting heterotetramers were purified (see “Materials and Methods”). The affinity of the SH2/BT2 complexes for the allosteric activator 3-PGA (Ka) was determined in the forward direction (G-1-P + ATP → ADP-Glc + PPi). Interestingly, seven out of the 14 SH2 variants had a higher Ka compared with wild-type SH2/BT2 (Table I). The overwhelming majority of them (six of seven) had an amino acid change in a site at the subunit interfaces. Two changes were in the head-to-head interaction areas (H149S, S163F), while four (T361C, D368S, P372A, C382F) were in the tail-to-tail interaction areas (Fig. 4). One change (Q213H) was in the N-terminal catalytic domain far from the subunit interfaces (Supplemental Fig. S2). The affinity for the deactivator Pi (Ki) was also determined in the presence of 15 mm 3-PGA by use of Dixon plots. Higher Ka values in the variants described above were accompanied by lower Ki (Table I). It has been proposed that 3-PGA and Pi are competing for binding to AGPase and that they may even bind to the same site (Boehlein et al., 2008). Therefore, the lower affinity for 3-PGA may maximize the efficiency of Pi inhibition.

Table I.

Kinetic and allosteric properties of the wild type and SH2 mutants in a complex with BT2

All reactions were performed in triplicate. The Hill coefficient for Ka values and Km values varies from 0.9 to 1.3. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with BT2/SH2 at P = 0.05. Statistical significance was estimated by an F test implemented by Prizm (GraphPad).

| Sample | Km G-1-P | Kcat | Km ATP | Ka 3-PGA | (15 mm 3-PGA) Ki Pi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mM | s−1 | mM | mM | mM | |

| BT2/SH2 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 39.17 ± 1.23 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 16.80 ± 3.84 |

| BT2/C114A | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 37.21 ± 1.78 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 13.23 ± 3.57 |

| BT2/H149S | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 35.21 ± 1.50 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 2.11 ± 0.13* | 3.96 ± 1.50* |

| BT2/S163F | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 34.65 ± 2.07 | 0.42 ± 0.09* | 3.29 ± 0.81* | 1.83 ± 0.96* |

| BT2/M172T | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 38.58 ± 1.98 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 17.61 ± 3.78 |

| BT2/Q213H | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 29.36 ± 1.72 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 3.01 ± 0.52* | 3.21 ± 1.13* |

| BT2/V227R | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 16.17 ± 1.06* | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 14.5 ± 4.01 |

| BT2/T361C | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 38.12 ± 1.62 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.05* | 5.34 ± 1.30* |

| BT2/D368S | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 23.34 ± 1.10* | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.11* | 4.26 ± 1.67* |

| BT2/P372A | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 42.32 ± 1.55 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 1.83 ± 0.15* | 3.72 ± 1.26* |

| BT2/C382F | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 40.75 ± 1.56 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.12* | 2.28 ± 1.12* |

| BT2/C424V | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 59.86 ± 3.45* | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 18.36 ± 4.43 |

| BT2/E438Q | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 32.87 ± 2.24 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 15.22 ± 3.34 |

| BT2/V502T | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 41.91 ± 3.13 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 17.93 ± 2.93 |

| BT2/A508S | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 35.77 ± 1.80 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 20.43 ± 4.25 |

The Km values for G-1-P and ATP were determined for all variants at 15 mm 3-PGA. Except for a 4-fold lower affinity of BT2/S163F for ATP, all the other variants exhibited indistinguishable and wild-type Km values. Similarly, most Kcat values were similar to wild-type BT2/SH2, except for BT2/C424V (approximately 150%), BT2/V227R (approximately 40%), and BT2/D368S (approximately 60%). This indicates that the allosteric changes in the variants affected the affinity for effectors to a much greater extent than the effect on the mechanism of activation.

The purified complex of SH2/BT2 is present in three forms: a heterotetramer, a heterodimer, and monomers of SH2 and BT2 (Boehlein et al., 2005). The SH2 and BT2 monomers have negligible activity at the levels of 3-PGA, G-1-P, and ATP used in this study (Burger et al., 2003). Additionally, Greene and Hannah (1998a) showed that the SH2/BT2 heterodimer is inactive. Therefore, all extant evidence strongly suggests that the AGPase activity in this study comes from the SH2/BT2 heterotetramer.

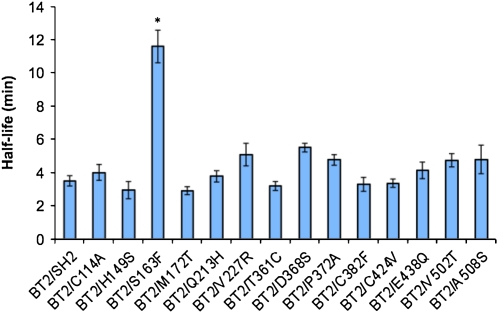

Heat Stability

The structures of the large and small subunits are almost identical. It has been shown that the loop connecting the C-terminal β-helix to the N-terminal catalytic domain in the small subunit is implicated in the heat stability of AGPase (Boehlein et al., 2009). This loop makes contact with the homologous loop in the large subunit, suggesting that the respective loop in the large subunit is also important for heat stability. Since nine out of 14 substitutions in SH2 were in sites located at the subunit interfaces, including the loop described above (amino acids 362–399), the heat stability of the resulting variants was determined. The variants and wild-type BT2/SH2 were heated for various amounts of time at 39°C, and remaining activity was determined by assaying in the forward direction using 20 mm 3-PGA and saturating amounts of substrates. With the exception of BT2/S163F, which showed a 3-fold increase in heat stability, all of the other variants were similar to wild-type BT2/SH2 (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the majority of the mutagenized sites at the subunit interfaces have a specific role only on the allosteric properties of AGPase.

Figure 6.

Heat stability of SH2 wild type and variants in a complex with BT2. The asterisk indicates a significant difference compared with wild-type BT2/SH2 at P = 0.05 (Student's t test; n = 6). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Correlation of Kinetic and Heat Stability Data with Glycogen Production

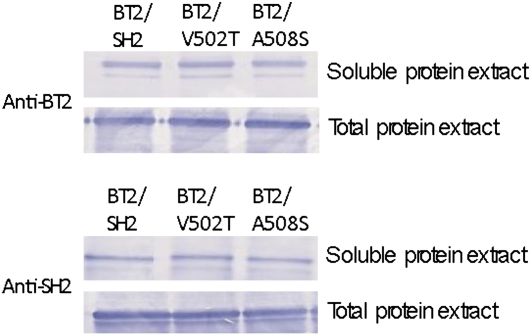

In general, the amount of glycogen produced by the variants in E. coli was consistent with the kinetic data. Six of seven allosteric variants produced lowered amounts of glycogen compared with the wild type. In the case of the exceptional BT2/S163F, the Ka was increased and hence decreased glycogen production might have been expected. This was not observed. However, the higher heat stability of BT2/S163F may counteract the increased Ka. As a result, BT2/S163F produces wild-type amounts of glycogen. BT2/M172T, BT2/C114A, and BT2/E438Q had wild-type kinetic properties and heat stability. Not surprisingly, they produced wild-type amounts of glycogen. BT2/V227R and BT2/C424V had lower and higher Kcat and glycogen production compared with the wild type, respectively. BT2/V502T and BT2/A508S exhibited wild-type kinetic properties and heat stability. However, glycogen production was markedly reduced in these mutants. Perhaps these variants have reduced solubility and/or increased susceptibility to proteases in E. coli, or perhaps transcription or translation is reduced in these mutants. These possibilities would predict reduced amounts of SH2 and/or BT2 protein in E. coli extracts. To investigate these possibilities, western-blot analysis was conducted on total and soluble protein extracts from E. coli expressing wild-type BT2/SH2, BT2/V502T, and BT2/A508S. The amount of SH2 and BT2 in both total and soluble protein extracts is indistinguishable from that in the wild type in these two variants (Fig. 7). Therefore, the possible explanations discussed above for the reduced glycogen produced by BT2/V502T and BT2/A508S should be excluded. The underlying reason for reduced glycogen production in these variants remains unresolved.

Figure 7.

Western blot of protein extracts from E. coli cells expressing SH2, V502T, and A508S along with BT2. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Interestingly, none of the SH2 variants gave a null phenotype in E. coli. The exact ratio of 3-PGA to Pi in our E. coli system is not known. Some tentative amounts for 3-PGA and Pi are 0.5 to 0.75 mm and 5 to 10 mm, respectively, depending on the type of cells and the growth conditions (Moses and Sharp, 1972; Ugurbil et al., 1978; Ishii et al., 2007). Since the ratio of 3-PGA to Pi is low, it may be expected that our AGPase variants have very low to almost no activity in E. coli. However, maize endosperm AGPase is known to have some low activity even in the absence of 3-PGA (5%–10% compared with the presence of saturating amounts of 3-PGA; Boehlein et al., 2009). Pi negates the presence of 3-PGA and brings the AGPase activity down to the level that is observed in the absence of 3-PGA (Boehlein et al., 2008). Further reduction of activity requires much higher amounts of Pi (Boehlein et al., 2009). This may explain why our allosteric variants do not show a null phenotype in our E. coli system.

DISCUSSION

Structure-function analysis of AGPase has attracted intense interest, since AGPase catalyzes a rate-limiting step in starch synthesis. An understanding of the specific role of amino acid sites or protein motifs can facilitate the engineering of AGPases, leading to greater starch yield in plants. A bacterial expression system has facilitated the understanding of plant AGPase function, since random mutagenesis and rapid screening of activity in E. coli are feasible. Detailed extant analyses have identified sites important for kinetic and allosteric properties and heat stability (Greene et al., 1996a, 1996b; Greene and Hannah, 1998b; Laughlin et al., 1998; Kavakli et al., 2001a, 2001b; Ballicora et al., 2007; Georgelis and Hannah, 2008; Hwang et al., 2008). Additionally, random mutagenesis of these variants has led to the identification of intragenic suppressors of initial mutants and resulted in the identification of additional sites that are important for allosteric properties of AGPase (Greene et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2007). Site-directed mutagenesis has also greatly facilitated structure-function analysis of AGPase. The resolved structure of the potato tuber small subunit homotetramer (Jin et al., 2005) along with structure modeling have been used to identify candidate sites for mutagenesis (Bejar et al., 2006; Hwang et al., 2006, 2007). Additionally, evolutionary comparison of AGPase with other pyrophosphorylases has identified conserved amino acid sites that have undergone site-directed mutagenesis (Ballicora et al., 1998, 2005; Fu et al., 1998; Frueauf et al., 2001, 2003).

Herein, we have identified positively selected sites in the large subunit of AGPase and amino acid sites that are conserved within large subunit groups but variable between groups. We argue that these sites may have been important in functional diversification of the large subunits and, subsequently, AGPases in plants. After placing these amino acid sites on the modeled structure of SH2, we observed that the majority of them were localized at tail-to-tail or head-to-head subunit interfaces. This strongly suggests that the subunit interfaces have been important in AGPase isoform specialization. To gain insight into the potential role of the amino acid sites, especially the ones located at subunit interfaces, we mutagenized 12 of these sites in SH2. We also mutagenized two type I sites that were located at subunit interfaces for reasons discussed above. The original amino acid in SH2 was replaced with an amino acid found in other large subunit groups.

Interestingly, 10 of 14 SH2 variants resulted in the synthesis of altered amounts of glycogen in E. coli. Additionally, nine of the SH2 variants showed distinct kinetic and allosteric properties compared with wild-type BT2/SH2. These results indicate that the majority of the amino acid changes are not neutral at the enzyme/physiological level, even though the replacement amino acids do exist in nature in other large subunits. This result supports and encourages the use of phylogenetic analysis software, such as PAML (for detection of positive selection; Yang, 1997) and DIVERGE (for detection of type I and II sites; Gu and Velden, 2002), in biochemical structure-function studies. DIVERGE and PAML were used by Georgelis et al. (2008) to detect the sites that were biochemically tested in this study.

Surprisingly, six of nine changes in SH2 that are located at subunit interfaces had altered allosteric properties. Indeed, these variants showed 2.4- to 10-fold increases in 3-PGA Ka and similar decreases in the Pi Ki. One substitution, S163F, also resulted in a 4-fold increase in the ATP Km, while change D368S resulted in a slight decrease in Kcat (approximately 60% of the wild type). Overall, Kcat values were not appreciably altered in the allosteric variants. Therefore, most of the changes in these variants were quite specific for Ka and Ki. This indicates that the changes introduced by mutagenesis primarily affected the affinity for the allosteric effectors rather than the mechanism of activation after effector binding. These results clearly indicate that subunit interfaces (both head-to-head and tail-to-tail interfaces) are important determinants of the affinity for allosteric effectors. The results also strongly suggest that the subunit interfaces have played an important role in enzyme function specialization, particularly in diversification in terms of affinity for the allosteric effectors, 3-PGA and Pi.

Based on the potato tuber small subunit homotetramer (Jin et al., 2005), one potential Pi-binding site (site 3) is formed by the head-to-head interaction area (Fig. 2). Two additional potential Pi-binding sites (sites 1 and 2) are between the N-terminal catalytic and C-terminal β-helix domains, with site 1 making contact with the loop that participates in tail-to-tail interactions (Fig. 2). Hence, the fact that the subunit interfaces are important for allosteric properties is consistent with the structural localization of the Pi-binding sites. However, most mutagenized sites are relatively far from the Pi-binding sites and could not directly bind allosteric effector molecules. This indicates that these sites would not have been selected for mutagenesis if only the structure of AGPase were considered in the experimental design.

Additional evidence pointing to the importance of the tail-to-tail interaction area in allosteric properties comes from studies with potato tuber AGPase (Kim et al., 2007). Here, an amino acid change in the loop connecting the β-helix to the catalytic domain of the potato tuber small subunit is important for the allosteric properties, although the site does not make direct contact with Pi. Overall, changes in the head-to-head and tail-to-tail interaction areas of either subunit are likely to affect allosteric properties, especially affinity for effector molecules, either because they directly make contact with the effectors or they change the orientation of amino acid residues that make direct contact with the effector molecules.

SH2 site 213 is also important in allosteric properties, although it is far from the subunit interfaces of the potential effector-binding sites (Supplemental Fig. S2). This is not the first case of a large subunit residue being important in allosteric properties yet far from the potential effector-binding sites. Site 230 was implicated in the allosteric properties of AGPase in a study of the potato tuber large subunit, although it is not close to effector sites or subunit interfaces. Site 230 was initially isolated through random mutagenesis, because its alteration suppressed the phenotype of an existing allosteric variant (Kavakli et al., 2001a). The finding that site 213 in SH2 is important for allosteric properties highlights the importance of phylogenetic analysis (site 230 was also identified in our evolutionary analysis). Phylogenetic analyses identify sites that are not readily targeted for mutagenesis based on structure alone. The most likely scenario is that changes in sites 213 and 230 indirectly affect allosteric properties by changing the structure of AGPase.

Since nine out of 15 SH2 variants were at or near subunit interfaces, we asked whether these alterations affected AGPase heat stability. Alteration in heat stability has been noted with at least one mutant (Greene and Hannah, 1998b) that affects large subunit-small subunit interactions. The loop connecting the N-terminal domain to the β-helix of the small subunit participates in tail-to-tail interactions with the large subunit and is important for AGPase heat stability (Boehlein et al., 2009). However, only one variant, BT2/S163F, showed altered heat stability. Either the specific changes were not sufficient to change heat stability or the specific sites are not important for heat stability in BT2/SH2.

Apart from altering allosteric properties, our site-directed mutagenesis specifically altered the specific activity of BT2/V227R and BT2/C424V. Site 227 is located in the N-terminal domain, while site 424 is in the C-terminal β-helix. Interestingly, BT2/C424V shows a 50% greater Kcat compared with wild-type BT2/SH2. This finding is supported by the fact that BT2/C424V produced almost 50% more glycogen compared with BT2/SH2 when expressed in E. coli. This variant alone or in combination with other existing variants may lead to agronomic gain when expressed in plants.

BT2/C424V is the only variant among four (424, 438, 502, 508; Supplemental Fig. S2) in the C-terminal β-helix (excluding the part that participates in subunit interactions) that exhibited an enzyme phenotype. However, this does not mean that the C-terminal β-helix is not important for enzyme function. Indeed, it makes direct contact with the effector-binding sites and in this way influences the allosteric properties of AGPase. Sites 441, 445, and 506 are important for allosteric properties (Ballicora et al., 1998; Kavakli et al., 2001a), and they were all detected by our phylogenetic analysis as either type II or positively selected sites.

Surprisingly, BT2/V502T and BT2/A508S synthesize markedly less glycogen in E. coli, even though their kinetic properties and heat stability are indistinguishable from the wild type. Decreased expression, decreased solubility, or increased protease susceptibility in E. coli are not likely explanations for reduced glycogen synthesis (Fig. 7). Perhaps these variants affect a form of regulation in E. coli that hitherto has escaped detection.

Collectively, our results indicate that the areas of the large subunit that participate in tail-to-tail and head-to-head interactions with the small subunit are crucial for the allosteric properties of AGPase. It was previously shown that the allosteric properties of AGPase are determined by the functional interaction between the large and small subunits (Cross et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2007). However, this is, to our knowledge, the first report that indicates that the interfaces between the large and small subunits are important for the allosteric properties and more specifically the affinity for 3-PGA and Pi. Additionally, the high proportion of type II and positively selected sites in these areas indicates that the subunit interfaces have been important in functional diversification of AGPase isoforms. These results are in accord with a biochemical study conducted by Crevillen et al. (2003) that indicated a functional specialization of the large subunit in terms of allosteric properties. However, this study pinpoints specific amino acids and areas in the large subunit that account for specialization in allosteric properties. This study also indicates that the specialization has taken place mainly in terms of the affinity for 3-PGA and Pi. Indeed, the mechanism of activation seems unaffected, since the Kcat values in the presence of activators or inhibitors of the vast majority of these mutants are very similar to wild-type AGPase.

Our mutagenesis also resulted in a change in site 424 that increased the specific activity of AGPase. This mutation may lead to agronomic gain when expressed in plants. The allosteric sites detected can also be targets of mutagenesis to obtain variants with low 3-PGA Ka and high Pi Ki that would also be of agronomic interest. Variants with low Ka and high Ki can also be achieved by isolation of intragenic suppressors of our allosteric variants through random mutagenesis.

Additionally, the results show that evolutionary analysis can substantially benefit structure-function studies. The present study is among the few examples where a large collection of positively selected and type II sites initially detected by phylogenetic analysis were verified biochemically. The fact that the majority of the changes in these sites are not neutral should encourage biochemists to use more evolutionary analysis to study enzyme structure-function relationships. In this study, evolutionary analysis led to the selection of several amino acid sites that are important for enzyme function. These sites would not have been selected based solely on the structure of AGPase. The majority of the type II and positively selected sites alter amounts of glycogen synthesized and/or enzymatic properties. Type I sites can also be useful in detecting sites important for function, since changes in type I sites 149 and 361 altered enzyme properties. However, a large-scale study should be conducted on type I sites to determine the false-positive rate.

Overall, this study enhanced our understanding of the evolution and structure-function relationships in AGPase, set the stage for protein engineering that may lead to increased starch yield in crops, and provided support for the use of evolutionary analysis to understand protein function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Alignment and Amino Acid Numbering

Maize (Zea mays) SH2 (accession no. P55241) and potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber large subunit (accession no. CAA43490) protein sequence alignment was obtained using MEGA software (Kumar et al., 2004) with BLOSUM matrix followed by manual inspection. The large subunit amino acid numbers used throughout this report correspond to SH2.

Structure Modeling

BT2, SH2, and the potato tuber large subunit monomer structures were modeled after the potato small subunit in the recently published three-dimensional structure of the potato tuber homotetrameric AGPase (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank no. 1YP2c). SWISS MODEL was used for performing homology modeling (Schwede et al., 2003; Arnold et al., 2006). The potato tuber large subunit and SH2 were modeled from amino acids 34 and 94 to the end, respectively, due to poor alignment of the N termini. WHATCHECK (Vriend, 1990) and VERIFY3D (Luthy et al., 1992) were used to structurally evaluate the models. The corresponding WHATCHECK values (z values for Ramachandran plot, backbone conformation, χ-1/χ-2 angle correlation, bond lengths, and bond angles) were within acceptable ranges. The high quality of the models was verified by the positive values assigned by VERIFY3D throughout all the structures. Visualization and superimposition of models and structures was done with Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

The PCR for site-directed mutagenesis was done with high-fidelity Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs) using pMONcSh2 as a template. The mutations were verified by double-pass sequencing performed by the Genome Sequencing Services Laboratory of the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research at the University of Florida. The following pairs of primers were used for generating C114A, H149S, S163F, M172T, Q213H, V227R, T361C, D368S, P372A, C382F, C424V, E438Q, V502T, and A508S, respectively: 5′-CCTGTTGGAGGAGCATACAGGCTTATTG-3′ and 5′-CAATAAGCCTGTATGCTCCTCCAACAGG-3′; 5′-CTTAACCGCCATATTTCTCGTACATACCTTG-3′ and 5′-CAAGGTATGTACGAGAAATATGGCGGTTAAG-3′; 5′-CAACTTTGCTGATGGATTTGTACAGGTATTAGC-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACCTGTACAAATCCATCAGCAAAGTTG-3′; 5′-GCGGCTACACAAACGCCTGAAGAGCCAG-3′ and 5′-CTGGCTCTTCAGGCGTTTGTGTAGCCGC-3′; 5′-CTTGAGTGGCGATCATCTTTATCGGATG-3′ and 5′-CATCCGATAAAGATGATCGCCACTCAAG-3′; 5′-CTTGTGCAGAAACATCGAGAGGACGATGCTG-3′ and 5′-CAGCATCGTCCTCTCGATGTTTCTGCACAAG-3′; 5′-GCAAACTTGGCCCTCTGTGAGCAGCCTTCC-3′ and 5′-GGAAGGCTGCTCACAGAGGGCCAAGTTTGC-3′; 5′-GCAGCCTTCCAAGTTTTCATTTTACGATCCAAAAACACC-3′ and 5′-GGTGTTTTTGGATCGTAAAATGAAAACTTGGAAGGCTGC-3′; 5′-GTTTGATTTTTACGATGCGAAAACACCTTTCTTC-3′ and 5′-GAAGAAAGGTGTTTTCGCATCGTAAAAATCAAAC-3′; 5′-CTTCACTGCACCCCGATTCTTGCCTCCGACGC-3′ and 5′-GCGTCGGAGGCAAGAATCGGGGTGCAGTGAAG-3′; 5′-CGTGTCAGCTCTGGAGTTGAACTCAAGGACTC-3′ and 5′-GAGTCCTTGAGTTCAACTCCAGAGCTGACACG-3′; 5′-GCGGACATCTATCAAACTGAAGAAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCTTCTTCAGTTTGATAGATGTCCGC-3′; 5′-GGTCTGGAATCACGGTGATCCTGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCAGGATCACCGTGATTCCAGACC-3′; and 5′-GATCCTGAAGAATTCAACCATCAACGATG-3′ and 5′-CATCGTTGATGGTTGAATTCTTCAGGATC-3′.

Glycogen Quantitation

Glycogen quantitation was performed by phenol reaction (Hanson and Phillips, 1981) as described by Georgelis and Hannah (2008).

Enzyme Expression and Purification

The SH2 wild type and variants were expressed along with wild-type BT2 in Escherichia coli AC70R1-504 cells (Iglesias et al., 1993). Briefly, AC70R1-504 cells containing wild-type Bt2 were transformed with plasmids containing each of the variant Sh2 genes. Transformation mixes were diluted and grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 75 μg mL−1 spectinomycin and 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin. Glycogen amounts were determined in cells grown in the presence 2% (w/v) Glc until optical density at 600 nm was around 2.0. For enzyme purification, cells were induced for 4 h with 0.2 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside and 0.02 mg mL−1 nalidixic acid after cells had reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. The resulting enzymes were purified as described by Georgelis and Hannah (2008). In brief, cell paste was harvested by centrifuging at 5,000g for 10 min, and the cells were lysed using a French press. AGPase was purified by protamine sulfate and ammonium sulfate fractionation, followed by anion-exchange and affinity (hydroxyapatite) chromatography. AGPase was concentrated, desalted, and exchanged into 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm EDTA before use. Bovine serum albumin (0.5 mg mL−1) was added to confer stability to AGPase. Purified AGPase was stored at −80°C.

Enzyme Kinetics

The forward direction of the reaction was used (G-1-P + ATP → ADP-Glc + PPi) for estimating Kcat, Km for ATP and G-1-P, and affinities for 3-PGA (Ka) and Pi (Ki). Specifically, 0.04 to 0.12 μg of purified enzyme was assayed, at 37°C for 10 min, in the presence of 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 15 mm MgCl2, 2.5 mm ATP, 2.0 mm G-1-P, and varying amounts of 3-PGA to determine Ka. Ki was determined in the presence of 15 mm 3-PGA. Km values for G-1-P and ATP were estimating by varying the amount of G-1-P and ATP, respectively, in the presence of 15 mm 3-PGA. The reaction was terminated by boiling for 2 min, and PPi was coupled to a reduction in NADH concentration using a coupling reagent as described by Georgelis and Hannah (2008). The kinetic constants were calculated with Prism 4.0 (GraphPad). The Hill coefficients were calculated as described by Cross et al. (2004). The specific activity was linear with time and amount of AGPase for all AGPase variants under all conditions.

Heat Stability

Heat stability of the SH2 wild type and variants expressed with wild-type BT2 was determined as described by Georgelis and Hannah (2008). The enzyme was heated at 39°C.

Western-Blot Detection of SH2 and BT2

Western-blot detection of both BT2 and SH2 in BT2/SH2, BT2/V502T, and BT2/A508S variants was performed as described by Georgelis and Hannah (2008). A polyclonal antibody against SH2 (1:2,000, v/v) was used in addition to a polyclonal antibody against BT2 to detect both SH2 and BT2.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers P55241 and CAA43490.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Amino acid tree of AGPase large subunits in angiosperms.

Supplemental Figure S2. Placement of SH2 sites 213, 424, 502, and 508 on the modeled SH2 structure.

Supplemental Table S1. Type II and positively selected sites in the large subunit of AGPase (Georgelis et al., 2008).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jon Stewart and Sue Boehlein for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. IBN–0444031 and IOS–0815104 to L.C.H.) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Competitive Grants Program (grant nos. 2006–35100–17220 and 2008–35318–18649 to L.C.H.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: L. Curtis Hannah (hannah@mail.ifas.ufl.edu).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Akihiro T, Mizuno K, Fujimura T (2005) Gene expression of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase and starch contents in rice cultured cells are cooperatively regulated by sucrose and ABA. Plant Cell Physiol 46 937–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T (2006) The SWISS-MODEL Workspace: a Web-based environment for protein structure homology modeling. Bioinformatics 22 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Dubay JR, Devillers CH, Preiss J (2005) Resurrecting the ancestral enzymatic role of a modulatory subunit. J Biol Chem 280 10189–10195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Erben ED, Yazaki T, Bertolo AL, Demonte AM, Schmidt JR, Aleanzi M, Bejar CM, Figueroa CM, Fusari CM, et al (2007) Identification of regions critically affecting kinetics and allosteric regulation of the Escherichia coli ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase by modeling and pentapeptide-scanning mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 189 5325–5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Fu Y, Nesbitt NM, Preiss J (1998) ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase from potato tubers: site-directed mutagenesis studies of the regulatory sites. Plant Physiol 118 265–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar CM, Jin X, Ballicora MA, Preiss J (2006) Molecular architecture of the glucose 1-phosphate site in ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylases. J Biol Chem 281 40473–40484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JG (2005) Directed mutagenesis confirms the functional importance of positively selected sites in polygalacturonase inhibitor protein. Mol Biol Evol 22 1531–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlein SK, Sewell AK, Cross J, Stewart JD, Hannah LC (2005) Purification and characterization of adenosine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase from maize/potato mosaics. Plant Physiol 138 1552–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlein SK, Shaw JR, Stewart JD, Hannah LC (2008) Heat stability and allosteric properties of the maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase are intimately intertwined. Plant Physiol 146 289–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlein SK, Shaw JR, Stewart JD, Hannah LC (2009) Characterization of an autonomously activated plant adenosine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 149 318–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger BT, Cross J, Shaw JR, Caren J, Greene TW, Okita TW, Hannah LC (2003) Relative turnover numbers of maize endosperm and potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylases in the absence and presence of 3-PGA. Planta 217 449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavatorta JR, Savage AE, Yeam I, Gray SM, Jahn MM (2008) Positive Darwinian selection at single amino acid sites conferring plant virus resistance. J Mol Evol 67 551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courville P, Urbankova E, Rensing C, Chaloupka R, Quick M, Cellier MF (2008) Solute carrier 11 cation symport requires distinct residues in transmembrane helices 1 and 6. J Biol Chem 283 9651–9658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevillen P, Ballicora MA, Merida A, Preiss J, Romero JM (2003) The different large subunit isoforms of Arabidopsis thaliana ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase confer distinct kinetic and regulatory properties to the heterotetrameric enzyme. J Biol Chem 278 28508–28515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevillen P, Ventriglia T, Pinto F, Orea A, Merida A, Romero JM (2005) Differential pattern of expression and sugar regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase-encoding genes. J Biol Chem 280 8143–8149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, Clancy M, Shaw J, Boehlein S, Greene T, Schmidt R, Okita T, Hannah LC (2005) A polymorphic motif in the small subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase modulates interactions between the small and large subunits. Plant J 41 501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, Clancy M, Shaw J, Greene TW, Schmidt RR, Okita TW, Hannah LC (2004) Both subunits of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase are regulatory. Plant Physiol 135 137–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueauf JB, Ballicora MA, Preiss J (2001) Aspartate residue 142 is important for catalysis by ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 276 46319–46325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueauf JB, Ballicora MA, Preiss J (2003) ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase from potato tuber: site-directed mutagenesis of homologous aspartic acid residues in the small and large subunits. Plant J 33 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Ballicora MA, Preiss J (1998) Mutagenesis of the Glc-1-phosphate-binding site of potato tuber ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 117 989–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Braun EL, Hannah LC (2008) Duplications and functional divergence of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase genes in plants. BMC Evol Biol 8 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Braun EL, Shaw JR, Hannah LC (2007) The two AGPase subunits evolve at different rates in angiosperms, yet they are equally sensitive to activity-altering amino acid changes when expressed in bacteria. Plant Cell 19 1458–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Hannah LC (2008) Isolation of a heat-stable maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase variant. Plant Sci 175 247–254 [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Chantler SE, Kahn ML, Barry GF, Preiss J, Okita TW (1996. a) Mutagenesis of the potato ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase and characterization of an allosteric mutant defective in 3-phosphoglycerate activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 1509–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Hannah LC (1998. a) Maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase SHRUNKEN2 and BRITTLE2 subunit interactions. Plant Cell 10 1295–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Hannah LC (1998. b) Enhanced stability of maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is gained through mutants that alter subunit interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 13342–13347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Kavakli IH, Kahn M, Okita TW (1998) Generation of up-regulated allosteric variants of potato ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase by reversion genetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 10322–10327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Woodbury RL, Okita TW (1996. b) Aspartic acid 413 is important for the normal allosteric functioning of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 112 1315–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribaldo S, Casane D, Lopez P, Philippe H (2003) Functional divergence prediction from evolutionary analysis: a case study of vertebrate hemoglobin. Mol Biol Evol 20 1754–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X (1999) Statistical methods for testing functional divergence after gene duplication. Mol Biol Evol 16 1664–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X (2006) A simple statistical method for estimating type-II (cluster-specific) functional divergence of protein sequences. Mol Biol Evol 23 1937–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Velden K (2002) DIVERGE: phylogeny-based analysis for functional-structural divergence of a protein family. Bioinformatics 18 500–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC (2005) Starch synthesis in the maize endosperm. Maydica 50 497–506 [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC, Nelson OE Jr (1976) Characterization of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Shrunken-2 and brittle-2 mutants of maize. Biochem Genet 14 547–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RS, Phillips JA (1981) Chemical composition. In P Gerhandt, RGE Murray, RN Costilow, EW Nester, WA Wood, NR Krieg, GB Phillips, eds, Manual of Methods for General Bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp 328–364

- Hwang SK, Hamada S, Okita TW (2006) ATP binding site in the plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit. FEBS Lett 580 6741–6748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Hamada S, Okita TW (2007) Catalytic implications of the higher plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit. Phytochemistry 68 464–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Nagai Y, Kim D, Okita TW (2008) Direct appraisal of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit in enzyme function by study of a novel mutant form. J Biol Chem 283 6640–6647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Salamone PR, Okita TW (2005) Allosteric regulation of the higher plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is a product of synergy between the two subunits. FEBS Lett 579 983–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias A, Barry GF, Meyer C, Bloksberg L, Nakata P, Greene T, Laughlin MJ, Okita TW, Kishore GM, Preiss J (1993) Expression of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 268 1081–1086 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Nakahigashi K, Baba T, Robert M, Soga T, Kanai A, Hirasawa T, Naba M, Hirai K, Hoque A, et al (2007) Multiple high-throughput analyses monitor the response of E. coli to perturbations. Science 316 593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Ballicora MA, Preiss J, Geiger JH (2005) Crystal structure of potato tuber ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase. EMBO J 24 694–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavakli IH, Greene TW, Salamone PR, Choi SB, Okita TW (2001. b) Investigation of subunit function in ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281 783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavakli IH, Park JS, Slattery CJ, Salamone PR, Frohlick J, Okita TW (2001. a) Analysis of allosteric effector binding sites of potato ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase through reverse genetics. J Biol Chem 276 40834–40840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Hwang SK, Okita TW (2007) Subunit interactions specify the allosteric regulatory properties of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 362 301–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M (2004) MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5 150–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin MJ, Payne JW, Okita TW (1998) Substrate binding mutants of the higher plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Phytochemistry 47 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linebarger CR, Boehlein SK, Sewell AK, Shaw J, Hannah LC (2005) Heat stability of maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is enhanced by insertion of a cysteine in the N terminus of the small subunit. Plant Physiol 139 1625–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D (1992) Assessment of protein models with 3-dimensional profiles. Nature 356 83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses V, Sharp PB (1972) Intermediary metabolite levels in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol 71 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Yang Z (1998) Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics 148 929–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrgård MA, Ivarsson Y, Tars T, Mannervik B (2006) Alternative mutations of a positively selected residue elicit gain or loss of functionalities in enzyme evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 4876–4881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohdan T, Francisco PB Jr, Sawada T, Hirose T, Terao T, Satoh H, Nakamura Y (2005) Expression profiling of genes involved in starch synthesis in sink and source organs of rice. J Exp Bot 56 3229–3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H, Casane D, Gribaldo S, Lopez P, Meunier J (2003) Heterotachy and functional shift in protein evolution. IUBMB Life 55 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC (2003) SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res 31 3381–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuncel A, Kavakli IH, Keskin O (2008) Insights into subunit interactions in the heterotetrameric structure of potato ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Biophys J 95 3628–3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugurbil K, Rottenberg H, Glynn P, Shulman RG (1978) 31P nuclear magnetic resonance studies of bioenergetics and glycolysis in anaerobic Escherichia coli cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75 2244–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventriglia T, Kuhn ML, Ruiz MT, Ribeiro-Pedro M, Valverde F, Ballicora MA, Preiss J, Romero JM (2008) Two Arabidopsis ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunits (APL1 and APL2) are catalytic. Plant Physiol 148 65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriend G (1990) What If: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph 8 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z (1997) PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci 13 555–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Krabbe Pedersen AM (2000) Codon-substitution models for heterogenous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics 155 431–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.