Abstract

We report a role for the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) RESURRECTION1 (RST1) gene in plant defense. The rst1 mutant exhibits enhanced susceptibility to the biotrophic fungal pathogen Erysiphe cichoracearum but enhanced resistance to the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria brassicicola. RST1 encodes a novel protein that localizes to the plasma membrane and is predicted to contain 11 transmembrane domains. Disease responses in rst1 correlate with higher levels of jasmonic acid (JA) and increased basal and B. cinerea-induced expression of the plant defensin PDF1.2 gene but reduced E. cichoracearum-inducible salicylic acid levels and expression of pathogenesis-related genes PR1 and PR2. These results are consistent with rst1's varied resistance and susceptibility to pathogens of different life styles. Cuticular lipids, both cutin monomers and cuticular waxes, on rst1 leaves were significantly elevated, indicating a role for RST1 in the suppression of leaf cuticle lipid synthesis. The rst1 cuticle exhibits normal permeability, however, indicating that the disease responses of rst1 are not due to changes in this cuticle property. Double mutant analysis revealed that the coi1 mutation (causing defective JA signaling) is completely epistatic to rst1, whereas the ein2 mutation (causing defective ethylene signaling) is partially epistatic to rst1, for resistance to B. cinerea. The rst1 mutation thus defines a unique combination of disease responses to biotrophic and necrotrophic fungi in that it antagonizes salicylic acid-dependent defense and enhances JA-mediated defense through a mechanism that also controls cuticle synthesis.

Plants are constantly exposed to a variety of pathogenic microbes that often suppress plant growth and decrease crop yield. Plant resistance to these diverse pathogens is controlled by multiple plant defense pathways, which include both constitutive and inducible factors. Salicylic acid (SA) is a primary signal against biotrophic pathogens, whereas jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET), and oleic acid (OA; 18:1 fatty acid) are utilized as primary signaling compounds activated in response to necrotrophic infections (Kachroo et al., 2003a, 2003b; Loake and Grant, 2007).

For biotrophs, gene-for-gene resistance is one of the strongest forms of plant defense, wherein the product of a plant R gene recognizes, either directly or indirectly, race-specific elicitors produced by the pathogen. This type of resistance is often coupled to the hypersensitive response (Dangl and Jones, 2001). Pathogen-induced hypersensitive response is often associated with activation of SA-dependent defense mechanisms, which leads to systemic acquired resistance (SAR) characterized by an increase in endogenous SA, transcriptional activation of PATHOGENESIS-RELATED (PR) genes PR1, PR2, PR5, and GLUTATHIONE-S-TRANSFERASE1, and protection against biotrophic pathogens (Cao et al., 1997; Reuber et al., 1998; Dewdney et al., 2000). SA is thought to be necessary for SAR, since the removal of SA blocks the onset of SAR (Gaffney et al., 1993). SA accumulation in plants, either by genetic modification of SA metabolism or exogenous SA application, induces SAR (Malamy et al., 1990, 1992; Métraux et al., 1990; Rasmussen et al., 1991; Yalpani et al., 1991; Enyedi et al., 1992). On the other hand, JA, ET, and OA are signal molecules required for defense responses to necrotrophic pathogens such as Botrytis cinerea (Thomma et al., 1999; Kachroo et al., 2001; Diaz et al., 2002; Ferrari et al., 2003). Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants with altered JA and/or ET signaling or biosynthesis, or the synthesis of OA, show increased susceptibility to the necrotrophs B. cinerea and Alternaria brassicicola (Thomma et al., 1999; Kachroo et al., 2001; Nandi et al., 2005). Transcription of the plant defense genes PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 is enhanced in response to B. cinerea and A. brassicicola infection and is dependent on ET, JA, and OA signals (Epple et al., 1995; Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998; Kachroo et al., 2003a, 2003b). Recent studies demonstrate cross talk between these signaling networks, revealing antagonistic relationships between the SA and JA/ET signaling pathways and an associated role for OA (Doares et al., 1995; Kunkel and Brooks, 2002; Kachroo et al., 2003a, 2003b). As a case in point, eds4 and pad4 mutants that are deficient in SA accumulation have impaired responses to SA and display enhanced JA-regulated gene expression (Gupta et al., 2000)

The cuticle, composed primarily of free epicuticular and intracuticular waxes and an insoluble polymer composed primarily of cutin, covers the aerial epidermal cell walls of plants and serves as the outermost boundary between the plant and its environment (Nawrath, 2002, 2006; Goodwin and Jenks, 2005). Besides their role in abiotic stress tolerance, chemical components of the cuticle are thought to play an important role in plant defense against fungal (Jenks et al., 1994) and bacterial (Xiao et al., 2004) pathogens, potentially through direct influence on innate immunity (Reina-Pinto and Yephremov, 2009) and/or perception (or generation) of signals required for SAR (Xia et al., 2009). Saturated, desaturated, and hydroxylated fatty acids are major substrates for cuticle lipid synthesis and have been implicated in barley (Hordeum vulgare) and rice (Oryza sativa) resistance to Erysiphe graminis and Magnaporthe grisea, respectively (Schweizer et al., 1994, 1996). Cutin monomers have been shown to induce developmental processes in pathogenic fungi such as the germination and formation of appressoria in the rice blast fungus M. grisea and appressorial tube formation in E. graminis (Francis et al., 1996; Gilbert et al., 1996). Additionally, both cutin monomers and cuticular waxes serve as general elicitors of plant defense response pathways (Fauth et al., 1998). Mutations that cause increased cuticle permeability, such as occurs in the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase2 (lacs2) mutant, provide full immunity to B. cinerea and Sclerotiorum sclerotinia (Chassot et al., 2007). Mutation in the α/β-hydrolase-encoding BODYGUARD (BDG) gene and ectopic expression of a fungal cutinase in Arabidopsis (CUTE) likewise increase cuticle permeability and confer enhanced resistance to B. cinerea (Sieber et al., 2000; Kurdyukov et al., 2006; Chassot et al., 2007). It is still unclear, however, whether this resistance is due to changes in plant defense response signaling resulting from altered cuticle properties, from enhanced secretion of antifungal or effector compounds, or from some other undiscovered mechanism.

We recently described the Arabidopsis resurrection1 (rst1) mutant as having altered cuticular waxes (Chen et al., 2005). In this report, biochemical analyses were expanded to reveal that the amount of cutin monomers was significantly elevated on rst1 leaves, just as previously reported for the waxes on rst1 leaves. Further analysis revealed that rst1 mutants were more susceptible to the obligate biotrophic fungus Erysiphe cichoracearum but more resistant to the necrotrophic fungi B. cinerea and A. brassicicola. Analysis of defense gene expression and SA and JA levels in rst1 suggests that SA-dependent defense responses are attenuated, whereas JA-dependent defense is enhanced. A novel role for RST1 and cuticle lipids in an antagonistic interaction between the SA- and JA/ET-mediated pathogen response pathways is described.

RESULTS

Loss-of-Function Mutation in RST1 Results in Enhanced Susceptibility to E. cichoracearum

The original rst1-1 mutant was identified from a T-DNA-mutagenized population of Arabidopsis in the C24 genetic background using visual screening for altered glaucousness of the inflorescence stem. The rst1-2 and rst1-3 allelic mutants were isolated from the SALK T-DNA insertion collection in the Columbia ecotype (Col-0) obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Chen et al., 2005). Transcript analysis by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR detected truncated RST1 transcripts in rst1-1 and rst1-3 (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Sequence analyses suggest that RST1 is a membrane-bound protein with 11 transmembrane domains (Supplemental Fig. S1B; Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993).

The rst1-1 mutant exhibited elevated susceptibility to E. cichoracearum under naturally occurring powdery mildew infections in the greenhouse (Supplemental Fig. S2). Although the C24 ecotype is completely immune to E. cichoracearum infection, the rst1-1 mutant showed extreme susceptibility to the pathogen. Subsequent studies of the rst1-2 and rst1-3 allelic mutants, as well as a pad4-1 positive control, clearly showed enhanced growth of E. cichoracearum on leaves relative to the normally susceptible Col-0 wild type (Fig. 1). Thus, RST1 contributes to resistance in both ecotypes. To clearly establish the role of RST1 in resistance to E. cichoracearum, inoculated leaves of Col-0, rst1-2, rst1-3, and pad4-1 were examined for fungal growth and development. Detached leaves from 4-week-old plants inoculated with a low density of conidia were assessed for the percentage of germinating conidia, hyphal length, and the number of conidiophores per colony at 1, 4, and 5 d post inoculation (dpi; Table I). At 1 dpi, no significant difference in the asexual spore germination and development of appressorial germ tubes for the wild type and the mutants was observed; however, from 2 to 4 dpi, E. cichoracearum hyphal growth became highly branched and produced more conidiophores on rst1-2 and rst1-3 plants compared with the wild type (Fig. 2A; Table I). At 5 dpi, E. cichoracearum produced two to four times more conidiophores on the rst1 mutants than on wild-type plants (Fig. 2B; Table I). Although rst1-2 and rst1-3 are allelic mutants, rst1-3 displayed more susceptibility to powdery mildew infection than rst1-2 (Table I). By comparison, the development of E. cichoracearum was marginally faster on the leaves of pad4-1 than on the rst1 mutants, with all mutants displaying more rapid pathogen development than wild-type plants (Fig. 2A). These observations indicate that E. cichoracearum colonizes rst1 mutant leaves more rapidly than wild-type leaves once the penetration peg growth phase is reached.

Figure 1.

Loss of RST1 function increases Arabidopsis susceptibility to E. cichoracearum. A, The rst1-2 and rst1-3 plants exhibit enhanced susceptibility to E. cichoracearum. The pad4-1 mutant shows susceptibility to powdery mildew and was used as a control for the disease assay. B, Constitutive expression of RST1 rescues the E. cichoracearum susceptibility of rst1-2 and rst1-3 to wild-type (Col-0) levels. Plants were grown on soil for 30 d and infected with E. cichoracearum. At least 10 plants were tested per genotype. Photographs were taken 10 to 14 dpi. The experiment was repeated at least three times, and representative results are shown. OE (overexpression) indicates plants expressing the RST1 genomic region including the introns from the CaMV 35S promoter (CaMV 35Spro:RST1).

Table I.

E. cichoracearum development on leaves of Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, rst1-2, and rst1-3 plants

Detached leaves were inoculated and incubated on petri plates as described in “Materials and Methods.” Leaves were fixed and stained with trypan blue.

| Genotype | Germinationa | Hyphal Lengthb | Conidiophores per Colonyc |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | mm | ||

| Col-0 | 62.1 (100)d | 0.887 ± 0.074 (8) | 8.9 ± 4.0 (7) |

| rst1-2 | 59.3 (100) | 1.053 ± 0.056 (7) | 19.3 ± 6.1 (9) |

| rst1-3 | 68.6 (100) | 1.188 ± 0.069 (9) | 46.8 ± 5.5 (9) |

Asexual spore germination measured at 1 dpi.

The length of secondary hyphae per germling measured at 4 dpi. Values are means ± sd.

Conidiophores were counted on five to six randomly selected single fungal colonies per leaf on three to five leaves at 5 dpi. Values are means ± sd.

Numbers within parentheses indicate the number of replicates.

Figure 2.

Microscopic analyses showing the growth of E. cichoracearum in inoculated plants. A, E. cichoracearum growth at 4 dpi showing hyphal branching on leaves of wild-type Col-0, rst1-2, rst1-3, and pad4-1 at 4 dpi. B, E. cichoracearum growth at 5 dpi showing sporulation in rst1-2 and rst1-3 leaves. Bottom panels of both A and B are magnified views of the boxes on the respective top panels. Representative samples are shown. The experiment was repeated at least three times. Bars = 100 μm.

To confirm genetic complementation, the RST1 gene including approximately 200 bp of both upstream and downstream untranslated regions was expressed in wild-type and rst1 plants. The overexpression of RST1 in the wild type does not affect responses to E. cichoracearum, whereas in the mutant, the RST1 gene rescued the E. cichoracearum susceptibility back to wild-type levels (Fig. 1B). Complementation tests using reciprocal crosses of rst1-2 with rst1-3 further confirmed that the observed phenotypes in the mutants are due to defects in RST1. All F1 plants resulting from crosses between the two mutant alleles exhibited a clear rst1 mutant glossy stem phenotype and enhanced disease susceptibility comparable to the parental mutant plants (data not shown). These results confirm that the phenotypes of rst1-2 and rst1-3 mutants are solely caused by defects in the RST1 gene.

The rst1 Mutant Has Elevated Levels of Leaf Cuticular Lipids But Displays Normal Cuticle Permeability

Previously, we showed that mutation in RST1 caused a 43% elevation in cuticular wax amounts on rst1 leaves (Chen et al., 2005). To provide a more complete analysis of leaf cuticle lipids, we examined the amount and composition of the leaf cutin monomers on wild-type Col-0 and the isogenic allelic mutants rst1-2 and rst1-3. Overall, the total amount of cutin monomers was significantly higher in both rst1-2 (16.4%) and rst1-3 (32.1%) compared with wild-type plants (Table II). Just as in their powdery mildew response, the rst1-3 mutation showed a stronger effect than rst1-2 on cutin monomers. In both allelic mutants, the C18:2 dicarboxylic acids were significantly higher than wild-type levels, rising from 47.5% of the total cutin monomers in the wild type to 56.2% and 66.3% of total cutin monomers for rst1-2 and rst1-3, respectively (Table II). Other cutin monomers changed very little in these allelic mutants (Table II). As such, both cuticular wax (Chen et al., 2005) and cutin amount per leaf area are significantly elevated in the rst1 mutants. Since the leaf areas of rst1-2 and rst1-3 are unchanged from their isogenic wild-type parent (data not shown), both cutin and wax synthetic pathways appear to have been activated by the mutation in RST1.

Table II.

Effects of the rst1 mutation on Arabidopsis leaf cutin monomers

The amount (μg dm−2) of total cutin monomers was higher in rosette leaves of the two isogenic allelic mutants rst1-2 and rst1-3 than in wild-type Col-0, due primarily to an increase in C18:2 dicarboxylic acids. Values represent means ± sd (n = 5). Asterisks indicate significant differences from the wild-type Col-0 amount as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05).

| Cutin Monomersa | Col-0 | rst1-2 | rst1-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16-OH C16:0 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| 10(9),16-OH C16:0 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 1.2 |

| C16:0 dioic acid | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 8.1 ± 0.7 |

| 18-OH C18:2 | 5.2 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 1.7 |

| 18-OH C18:1 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| 18-OH C18:0 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| C18:2 dioic acid | 47.5 ± 4.5 | 56.2 ± 0.2* | 66.3 ± 7.7* |

| C18:1 dioic acid | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 1.3 | 5.9 ± 0.3 |

| C18:0 dioic acid | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Total | 73.0 ± 6.0 | 84.8 ± 3.8* | 96.4 ± 8.0* |

16-OH C16:0, 16-Hydroxy hexadecanoic acid; 10(9),16-OH C16:0, 10(9),16-dihydroxy hexadecanoic acid; C16:0 dioic acid, hexadecane-1,16-dioic acid; 18-OH C18:0, 18-hydroxy octadecanoic acid; 18-OH C18:1, 18-hydroxy octadec-9-enoic acid; 18-OH C18:2, 18-hydroxy octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid; C18:0 dioic acid, octadecane-1,18-dioic acid; C18:1 dioic acid, octadecene-1,18-dioic acid; C18:2 dioic acid, octadecadien-1,18-dioic acid. OH denotes a hydroxyl functional group.

Previous studies have implicated leaf permeability due to altered cuticle composition as a factor in pathogen response, so we examined leaf permeability of rst1 using measures of transpiration rate, stomatal index, toluidine blue staining, and sensitivity to xenobiotics as criteria. Transpiration rates of detached leaves of soilless medium-grown rst1 plants did not differ from those of the wild type. Moreover, sensitivity to herbicide (BASTA) was not significantly different between the wild type and rst1, nor did the leaves of rst1 and the wild type show differences in the rate of uptake of toluidine blue stain (Supplemental Figs. S3–S5). Additionally, no difference was observed in stomatal index or trichome number of the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces on rst1 compared with the wild type (Chen et al., 2005). These results provide strong evidence that, although rst1 has an increased amount of leaf cutin monomers and cuticular waxes, these cuticular modifications cause no significant changes in general leaf cuticle membrane permeability, although it is possible that permeability to specific chemical(s) has been altered.

The rst1 Mutant Has Attenuated SA-Dependent Defense to E. cichoracearum

To determine whether enhanced susceptibility to E. cichoracearum in rst1 is associated with altered defense responses, we determined the expression of defense genes PR1, PR2, and PDF1.2 following E. cichoracearum or B. cinerea inoculation. The expression of both PR1 and PR2 was slightly elevated in noninoculated rst1-2 and rst1-3 compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S6). After E. cichoracearum infection, both the wild type and mutants showed a dramatic induction of PR1 and PR2 transcripts (Fig. 3). However, induction of PR1 and PR2 in rst1-2 and rst1-3 was much less than in Col-0, averaging 21% to 26% and 11% to 14%, respectively, of wild-type induction levels. The lower expression of these PR genes in rst1-3 than in rst1-2 corresponds well with the relatively greater increase in susceptibility of rst1-3 over rst1-2 to E. cichoracearum (Table I). Both noninoculated and inoculated pad4 mutants show very low levels of PR1 and PR2 expression (Fig. 3). Expression of the PDF1.2 gene, a marker for JA/ET-dependent defense responses, was increased in rst1-2, rst1-3, and pad4-1 compared with the wild type following E. cichoracearum infection (Fig. 3). The RST1 gene is also responsive to pathogen infection, with expression in the wild type being slightly induced in response to E. cichoracearum (Fig. 3). The expression of SA signaling genes NPR1 and PAD4 is significantly reduced in the rst1 mutants relative to the wild type. We next examined the accumulation of SA in wild-type, rst1, and pad4 plants with and without powdery mildew inoculation. The amount of SA was not altered in rst1-2 and rst1-3 compared with the wild type in noninoculated plants (Fig. 4). However, in the rst1-2 and rst1-3 mutants, accumulation of SA after inoculation with E. cichoracearum was severely reduced relative to wild-type plants (Fig. 4), providing further evidence for an association between SA synthesis or accumulation and RST1 function. Thus, RST1 is required for normal pathogen-induced SA accumulation and downstream responses.

Figure 3.

Basal and E. cichoracearum-induced expression of defense response and RST1 genes. Quantitative RT-PCR data showing the expression of the SA pathway defense genes PR1, PR2, PAD4, and NPR1 and the ET/JA-pathway defense genes PDF1.2 and RST1. Total RNA was extracted from leaves of plants at 7 dpi. Arabidopsis TUBULIN was used as an internal control. Control samples were normalized to 1. Values represent means ± sd (n = 4).

Figure 4.

The rst1 mutants accumulate less SA than the wild type after E. cichoracearum inoculation. The amount of free SA in leaves from 4-week-old plants was analyzed using HPLC. Samples were collected with or without E. cichoracearum infection at 7 dpi. Values represent means ± sd (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight.

The rst1 Mutant Displays Enhanced Resistance to Necrotrophic Pathogens A. brassicicola and B. cinerea

To determine the effects of impaired RST1 function on plant responses to necrotrophic pathogens, we examined the response of rst1 to A. brassicicola and B. cinerea. The rst1-2 and rst1-3 mutants displayed elevated resistance to both necrotrophs relative to the wild type based on disease symptoms and pathogen growth (Figs. 5 and 6A). The size of disease lesions on inoculated leaves of B. cinerea was approximately 3-fold smaller than on the wild type (Fig. 6B). The inoculated rst1 mutant alleles supported significantly lower pathogen sporulation and showed confined disease lesions, suggesting that rst1 suppresses pathogen growth and disease symptoms. Consistent with restoration of E. cichoracearum resistance in rst1 plants expressing the wild-type RST1 gene (Fig. 1B), B. cinerea susceptibility was restored to wild-type levels in rst1 mutants expressing the 35Spro:RST1 construct (as was the wild-type wax phenotype), further confirming that expression of the wild-type RST1 gene promotes infection by the necrotrophic fungi tested (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5.

The rst1 mutants exhibit enhanced susceptibility to the necrotrophic pathogen A. brassicicola. A, Disease symptoms on leaves of drop-inoculated wild-type and rst1 plants at 6 dpi. B, Spore count on A. brassicicola-inoculated plants at 4 dpi. Data represent means ± sd. The mean values were determined from three independent experiments. Each experiment contained an average spore count from 20 inoculated leaves per genotype.

Figure 6.

The rst1 mutants show enhanced resistance to the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. A, rst1 mutants show fewer disease symptoms on drop-inoculated leaves. Top row, Col-0, rst1-2, and rst1-3 plants at 3 dpi. Bottom row, rescued rst1 mutant phenotype of plants harboring CaMV 35Spro:RST1. B, Mean disease lesion size at 3 dpi with B. cinerea. Data represent means ± sd. The mean values were determined from three independent experiments. Each experiment contained the average lesion size from 20 inoculated leaves per genotype. OE, Overexpression.

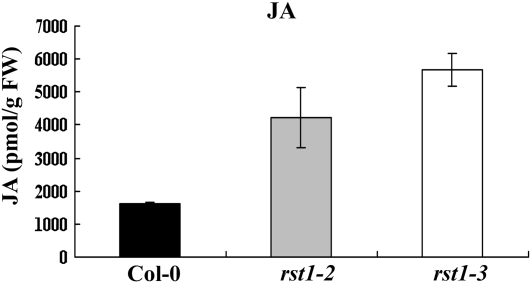

Expression of the plant defensin gene PDF1.2 positively correlates with activation of JA/ET-dependent defenses and resistance to necrotrophic pathogens (Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998). In an effort to further examine the role of RST1 in JA/ET-mediated defenses, we determined the expression levels of PDF1.2 in wild-type and rst1 plants at various time points after inoculation with B. cinerea, as described previously (Veronese et al., 2006). The expression of PDF1.2 in uninoculated rst1 plants was significantly higher than in wild-type plants. After inoculation, the expression continued to increase in both the wild-type and rst1 plants at comparable levels up to 24 h post inoculation (hpi). However, in the rst1 mutants, the expression of PDF1.2 surpassed that of the wild type by 48 hpi (Fig. 7A). After 48 h, PDF1.2 expression began to decline in wild-type plants but continued to increase in the rst1 mutants (Fig. 7A). The induced expression of the PDF1.2 gene was sustained in a manner consistent with the sustained resistance response to the pathogen. The highly induced expression of RST1 in wild-type plants at 48 hpi preceded the observed increase in PDF1.2 expression (Fig. 7B). Consistent with their observed disease responses, the rst1-2 and rst1-3 mutants had 2.6- to 3.5-fold higher basal levels of JA than the wild-type plants (Fig. 8). Together, these results demonstrate that RST1 regulates plant responses to A. brassicicola and B. cinerea, likely through the modulation of JA-dependent plant defenses.

Figure 7.

The expression of PDF1.2 and RST1 genes in B. cinerea-inoculated plants. A, The expression of PDF1.2 in wild-type, rst-2, and rst1-3 plants before inoculation and at 24, 48, and 60 hpi with B. cinerea. Asterisks indicate significant differences from wild-type Col-0 at each time point as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05). B, The expression of RST1 in wild-type Col-0 plants before and 24 and 48 hpi with B. cinerea. The data represent means ± sd. Mean values were determined from three independent experiments. Arabidopsis TUBULIN was used as an internal control. Control samples were normalized to 1 hpi. The asterisks indicates a significant difference from the 0-h time point as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

The rst1 mutants show increased basal JA accumulation. The basal amounts of JA in rst1-2 and rst1-3 is higher than that of Col-0. The levels of JA in leaves from 4-week-old soil-grown plants of Col-0, rst1-2, and rst1-3 were analyzed using HPLC-mass spectrometry. Values represent means ± sd (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight.

The Mutation of RST1 Appears to Induce Several JA-Regulated Genes and Elevates JA Levels

To determine the genome-wide effects of loss of RST1 function on gene expression, we performed transcriptome analysis of the rst1 mutant to obtain preliminary indications of genes that have altered transcript levels in the rst1 genetic background. Hundreds of genes were significantly up- and down-regulated in rst1 compared with the wild type (data not shown). The full set of the raw intensity microarray data are deposited at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, with GEO accession numbers GSE16875, GSM422925, GSM422926, and GSM422927. As a means to verify microarray data, we used RT-PCR to examine the expression of numerous genes revealed as highly expressed in the mutant array, including PR1, PR2, PDF1.2, BG1, GLYCOSYL HYDROLASE FAMILY19 (CHITINASE), and ATHILA RETROELEMENT, to find similar high expression (Figs. 3 and 7A; Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7). Of the genes that were up-regulated in rst1, six were associated with JA synthesis, two with JA signaling, and 18 were JA responsive, indicating a strong impact of the RST1 gene mutation on JA synthesis and signaling, results consistent with the elevated JA levels in the mutant (Table III). By comparison, ET synthesis-related genes were not altered in rst1, and only three ET-specific signaling or stimulus genes had elevated expression, albeit in the lower range (data not shown). Interestingly, the BG1 gene, whose product cleaves abscisic acid (ABA) from a glycosyl conjugate, shows extremely high expression in rst1, indicating an association of the general stress-responsive ABA with RST1 function (Table II). Furthermore, the PAD3 gene that encodes the cytochrome P450 protein required for the synthesis of the Arabidopsis phytoalexin camalexin was also up-regulated in rst1 (Table II). As such, the enhanced resistance of rst1 to B. cinerea and A. brassicicola may also involve enhanced phytoalexin accumulation. Furthermore, the FAD6 gene, whose product is involved in synthesis of fatty acids leading to the synthesis of JA and other lipid-related products, shows increased expression in rst1 compared with the wild type (Ferrari et al., 2007; Chaturvedi et al., 2008). Arabidopsis fad mutants show increased susceptibility to pathogen infection and insect attack (McConn et al., 1997; Staswick et al., 1998; Vijayan et al., 1998) providing further evidence for a complex regulatory function of RST1 in disease response.

Table III.

JA synthesis, perception, and response genes up-regulated in rst1 mutants

Annotation was based on The Arabidopsis Information Resource database (http://Arabidopsis.org). The expression fold change of probe sets is indicated only when change is significant (P ≤ 0.01 and P ≥ 2.0). Collected data were from three independent experiments and analyzed as indicated in “Results.”

| Description | AGI Code | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| JA biosynthesis | ||

| LOX2 | At3g45140 | 4.3 |

| LOX3 | At1g17420 | 2.2 |

| Putative LOX | At1g72520 | 2.1 |

| OPR3/DDE1 | At2g06050 | 2.1 |

| 4CL-like | At4g05160 | 2.4 |

| KAT2 | At2g33150 | 2.2 |

| JA-mediated signaling pathway | ||

| RCD1 | At1g32230 | 4.3 |

| SGT1B | A4g11260 | 2.4 |

| Response to JA stimulus | ||

| JAZ2 | At1g74950 | 2.1 |

| JAZ5 | At1g17380 | 2.2 |

| JAZ6 | At1g71030 | 2.0 |

| JAZ7 | At2g34600 | 2.0 |

| JAZ9 | At1g70700 | 2.2 |

| ATPRB1 | At2g14580 | 3.0 |

| TAT3 | At2g24850 | 3.5 |

| MYB2 | At1g52030 | 5.5 |

| CPL3/ETC3 | At4g01060 | 2.2 |

| F2N1_20 | At4g01280 | 2.0 |

| GSH1 | At4g23100 | 2.4 |

| JR2/CORI3 | At4g23600 | 3.9 |

| VSP2 | At5g24770 | 4.7 |

| PDF1.2a | At5g44420 | 5.4 |

| PDF1.2c | At5g44430 | 5.4 |

| PDF1.2b | At2g26020 | 5.1 |

| PDF1.3 | At2g26010 | 4.6 |

| Other pathogen-related genes | ||

| BG1 | At1g52400 | 16 |

| Chitinase | At2g43570 | 5.4 |

| Peroxidase50 | At4g37520 | 5.0 |

| PAD3 | At3g26830 | 4.8 |

| FAD6 | At4g30950 | 2.3 |

To further determine how RST1 interacts within the JA/ET-dependent defense pathways, we constructed double mutants rst1-2 coi1-1 and rst1-2 ein2-1. The coi1-1 and ein2-1 mutants are impaired in JA perception and ET signaling, respectively (Xie et al., 1998; Alonso et al., 1999). Both coi1 and ein2 show enhanced susceptibility to B. cinerea (Thomma et al., 1998, 1999). B. cinerea disease assays of double mutants reveal that coi1 is completely epistatic to rst1, whereas ein2 is partially epistatic to rst1 (Fig. 9). Thus, the resistance observed in the rst1 mutant to B. cinerea is dependent on functional COI1 and EIN2 genes. Taken together, these results implicate RST1 as a negative regulator for JA synthesis or signaling whose down-regulation enhances Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea and A. brassicicola.

Figure 9.

Effects of coi1 and ein2 mutations on the B. cinerea resistance of the rst1 mutant. A, Disease symptoms on drop-inoculated leaves of wild-type, single mutant, and double mutant plants at 3 dpi with B. cinerea. B, Mean disease lesion size in B. cinerea-inoculated plants at 3 dpi. Data represent means ± sd. The values were determined from three independent experiments. Each experiment contained measurements from lesions of 20 inoculated leaves per genotype. Disease assays were performed by drop inoculation of leaves on whole plants, and representative leaves were detached for pictures.

RST1 Has No Role in Plant Response to the Bacterial Pathogen Pseudomonas syringae

To determine whether the rst1 mutation affects responses to a bacterial pathogen, we inoculated rst1 plants with the virulent P. syringae pv tomato (Pst) strain DC3000 and the avirulent P. syringae DC3000 strain expressing avrRps4. No significant differences in bacterial growth and disease symptoms were observed between the wild types and their isogenic rst1 mutants (Supplemental Fig. S8). As previously reported, enhanced susceptibility was exhibited in pad4-1 and NahG plants to both the virulent Pst DC3000 and avirulent Pst DC3000 (avrRps4) strains (Feys et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2007). Thus, RST1 appears to have no role in basal defense response to P. syringae and RPS4-mediated race-specific resistance, indicating that RST1 has a certain level of pathogen specificity rather than being a general defense regulator.

The RST1 Transcript Is Expressed in Vascular and Anther Tissues, and the RST1 Protein Is Localized to the Plasma Membrane

To determine the spatial and temporal expression of RST1, we expressed a GUS reporter gene in Arabidopsis Col-0 under the control of a 1,200-bp fragment of the RST1 promoter region. The RST1pro:GUS construct was transformed into Arabidopsis using the floral dip method, and a total of eight independent transformants were used for expression analysis. Strong GUS activity was detected in the veins of leaves, petioles, and hypocotyls from 1-week-old seedlings and anthers of mature flowers (Fig. 10A). GUS activity was not easily detected in the inflorescence stem, root, cauline leaves, siliques, and seeds, consistent with a previous report (Chen et al., 2005) demonstrating that RST1 expression in those tissues is very low and best detected using PCR-based methods. The 35Spro:GUS vector control showed blue staining in essentially all tissues (data not shown). The expression of RST1 in anther tissues is consistent with its role in JA-related functions, as JA has been implicated in male fertility (Feys et al., 1994; Park et al., 2002).

Figure 10.

Tissue-specific expression of RST1pro:GUS-derived fusion protein and subcellular localization of RST1:GFP-derived fusion protein in Arabidopsis roots. A, Series of images showing GUS activity in transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing GUS under the control of the RST1 promoter. Two-week-old seedlings and leaves (top row) and the flowers from 8-week-old plants (bottom row) are shown. The white arrow indicates a pollen tube on the stamen of a flower. B, Subcellular localization of the CaMV 35Spro:RST1:GFP-derived fusion protein in the roots of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Subcellular localizations of RST1 (top row), GFP control (middle row), and no-vector control (bottom row) are shown.

The RST1 cDNA was fused to the GFP to examine the subcellular localization of the RST1 protein in root cells of transgenic plants. The cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35Spro:RST1:GFP (containing full-length RST1 cDNA) was transformed into rst1-2, and then transgenic plants were isolated from the T1 generation. Stem glossiness and seed abortion phenotypes were observed as being reverted to the wild type in the complemented lines. GFP localization within the T2 generation of these fully complemented lines was verified using the confocal microscope. The rescued phenotypes of rst1-2 provide strong evidence that the recombinant RST1 protein localized to the normal in situ location. Visualization of RST1:GFP root cell expression using confocal light microscopy provided results consistent with RST1 protein localization to the plasmalemma (Fig. 10B). To exclude autofluorescence signal from the cell wall (due to phenolics), we confirmed that green fluorescence was undetectable in Col-0 under the same conditions (Fig. 10B).

DISCUSSION

We describe the unique role of the Arabidopsis RST1 gene in regulating plant immunity to an obligate biotrophic pathogen and two species of necrotrophic fungi. Compared with the isogenic wild-type parents, the rst1 mutant is more resistant to the two necrotrophic fungi, B. cinerea and A. brassicicola, but more susceptible to the biotrophic fungus E. cichoracearum. By comparison, the response of rst1 to virulent and avirulent strains of the bacterial P. syringae did not differ from the wild type. Although many Arabidopsis mutants have been reported showing increased resistance to biotrophs but increased susceptibility to necrotrophs, rst1, to our knowledge, is the first plant mutant to show, in contrast, a clearly elevated resistance to necrotrophs but susceptibility to biotrophs. An Arabidopsis mutant like rst1 with a comparable disease phenotype, lacs2, in a similar way shows elevated resistance to the necrotroph B. cinerea and higher susceptibility to P. syringae (Tang et al., 2007). The P. syringae pathogen, however, is not a strict biotroph or an obligate parasite, as is E. cichoracearum, and as such, rst1 defines a unique defense response in this regard. Consistent with a role for SA in mediating resistance to biotrophs, many of the previously reported biotroph-resistant but necrotroph-susceptible mutants exhibit elevated levels of SA and enhanced cell death prior to or after infection (Epple et al., 2003; Bohman et al., 2004; Veronese et al., 2004; Nandi et al., 2005). The eds4 and pad4 mutants show enhanced susceptibility to biotrophs similar to rst1 and are also similarly deficient in SA accumulation, defective in SA responses, and exhibit enhanced expression of JA-mediated genes (Penninckx et al., 1996; Gupta et al., 2000). However, eds4 and pad4 do not exhibit increased resistance to necrotrophic pathogens (Ferrari et al., 2003; Dhawan et al., 2009), as does rst1. Several Arabidopsis mutations, including mpk4, bik1, and wrky33, impair JA- and ET- dependent plant defense responses and cause susceptibility to the necrotrophic pathogens A. brassicicola and/or B. cinerea (Petersen et al., 2000; Wiermer et al., 2005; Veronese et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2006). As such, MPK4, BIK1, and WRKY33 appear, along with RST1, to play a role in the antagonistic cross talk regulating the SA and JA pathogen-defense signaling pathways. The rst1 mutation, however, uniquely suppresses SA through the up-regulation of JA levels, rather than the reverse. A third group of Arabidopsis mutants show increased resistance to necrotrophic fungi without an apparent effect on SA defense responses (Penninckx et al., 2003; Coego et al., 2005). The Arabidopsis response to P. syringae is mediated by SA-dependent defense pathways. However, we observed no effect of the rst1 mutation on plant response to P. syringae despite rst1's reduced SA levels and SA-dependent responses. Whether the differences in cuticle lipids between the wild type and rst1 influence any of the differential responses to the bacterial pathogen P. syringae (a nonobligate pathogen) and the obligate biotrophic fungus and necrotrophic fungi examined here, either through physical or chemical cues, requires further investigation. The specificity of the susceptible responses in the rst1 mutant to an obligate biotrophic fungus, however, suggests that there may be a unique RST1-regulated pathogen response linked to cuticle production.

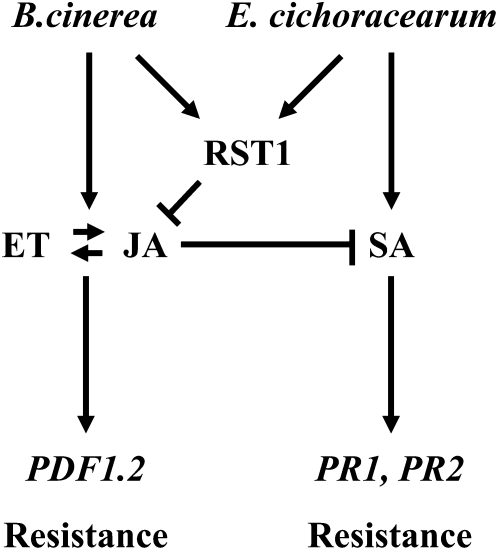

In spite of cross talk between these pathways, plant defense to biotrophs is primarily modulated by SA-dependent signaling, whereas defense to necrotrophs is primarily modulated by ET/JA-dependent signaling (Thomma et al., 1999; Dewdney et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2002; Ferrari et al., 2003). Based on our results, RST1 appears to be most closely associated with direct regulation of the JA-dependent defense pathways but likely has a strong indirect effect on SA signaling pathways as well. In support of a regulatory role of RST1 in JA signaling, the rst1 mutant exhibits increased basal expression of the PDF1.2 gene and enhanced PDF1.2 transcription upon necrotrophic infection. By comparison, the PR1 and PR2 genes are suppressed in rst1 after inoculation with the biotrophic pathogen E. cichoracearum. In addition, rst1 mutants have much lower SA levels compared with the wild type during biotrophic infection, indicating a negative effect of the rst1 mutation on SA signaling or synthesis. Transcriptome analysis reveals a surprisingly high induction of numerous JA synthesis genes in the rst1 mutant, suggesting that the wild-type RST1 protein likely serves as a suppressor of JA synthesis (just as RST1 appears to suppress cutin and wax synthesis). Previous reports show that activation of the JA defense pathway can have a suppressive effect on SA synthesis and associated gene expression (Petersen et al., 2000). Based on this, we hypothesize that in the absence of RST1, JA synthesis is elevated, leading to the suppression of SA synthesis and/or responses (Fig. 11). The increased susceptibility of rst1 to E. cichoracearum is consistent with this hypothesis, as resistance to obligate pathogens is primarily mediated through an SA-dependent pathway. Impaired or reduced SA synthesis or responses is known to reduce PR1 and PR2 gene expression and is associated with increased susceptibility to biotrophic pathogens. In this way, our results are consistent with the previously reported antagonistic interactions between the JA/ET- and SA-dependent pathways (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002; Spoel et al., 2003).

Figure 11.

A model for the function of RST1 as a modulator of plant defense through the suppression of JA biosynthesis.

A previous report on the rst1 mutant revealed that the RST1 gene is associated with cuticle wax synthesis and embryo development (Chen et al., 2005). The rst1 mutant exhibited a deficiency in stem cuticle waxes of 59% but an increase in rosette leaf waxes of 43% (primarily due to increased leaf alkanes of 31 and 33 carbon chain length). In this report, we show that the level of total leaf cutin monomers was increased as much as 32% above wild-type levels (due primarily to increased C18:2 dicarboxylic acids), indicating that the functional RST1 acts as a suppressor of both cutin monomer and wax production pathways. Similarly, the Arabidopsis bdg mutant (defective in an α/β-hydrolase fold-containing protein) had increased amounts of leaf cutin monomers and waxes and, like rst1, exhibited enhanced resistance to B. cinerea (Kurdyukov et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2007). The lacs2 mutant (defective in an acyl-CoA synthetase protein) also has increased B. cinerea resistance, but in contrast to rst1 and bdg, it has decreased cutin monomers, especially C18:2 dicarboxylic acids (Bessire et al., 2007; Chassot et al., 2007). In previous studies, it was speculated that the increased cuticle permeability of bdg and lacs2 may cause elevated secretion of antifungal compounds through a less restrictive cuticle, resulting in the increased B. cinerea resistance observed in bdg and lacs2 (Bessire et al., 2007). However, the rst1 mutant, in contrast to bdg and lacs2, does not show elevated permeability of its leaf cuticles relative to the wild type, indicating the existence of some other mechanism for rst1's resistance to necrotrophic infection. It is interesting that transcriptome analyses of another wax mutant, cer6 (defective in 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase required for very long-chain wax synthesis), revealed that many ET/JA- and SA-dependent defense genes were differentially expressed (Fiebig et al., 2000; Garbay et al., 2007) and indicated that cuticle metabolic pathways may play a direct role in modulating plant pathogen-defense-responsive pathways. Whether this cuticle modulation of plant defense occurs via physical factors or chemical signaling is still uncertain. Potentially, the increased amounts of cutin and cuticular wax on rst1 leaves could protect against fungal necrotrophs by creating a more significant physical barrier that restricts pathogen turgor- and cutinase/esterase-driven infection and penetration processes (Pascholati et al., 1992; Fric and Wolf, 1994; Nicholson and Kunoh, 1994; Zimmerli et al., 2004; Skamnioti and Gurr, 2007). The perturbation of SA signaling, JA-mediated responses, and SA and JA levels also raises the possibility that rst1's altered cuticle lipids could serve themselves as elicitors of plant defense responses (Lin and Kolattukudy, 1978; Woloshuk and Kolattukudy, 1986; Podila et al., 1988; Trail and Koeller, 1993; Francis et al., 1996; Li et al., 2002; Chassot and Métraux, 2005). Still, it cannot be dismissed that RST1 or its protein product could also act more directly as a regulatory or otherwise fungus-active compound, with cuticle modifications being a secondary effect of the RST1 defect.

Recent reports demonstrate that the 18:1 free fatty acid products of SSI2, a stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase, are important signaling determinants conferring resistance to B. cinerea through the JA signaling pathway (Kachroo et al., 2001; Chandra-Shekara et al., 2007; Chaturvedi et al., 2008). Although our microarray analysis of rst1 does not show altered SSI2 expression, a fatty acid desaturase gene, FAD6, is significantly induced in the rst1 background, indicating that lipid synthesis pathways other than cuticle lipid pathways may also be affected by the rst1 mutation. Furthermore, a previous report showed that the rst1 mutation blocks the synthesis of seed storage lipids derived from triacylglycerols (Chen et al., 2005). The effect of RST1 expression on multiple lipid synthetic pathways raises intriguing questions about the function of RST1 in generating lipids that might have signaling roles in plant pathogen interactions. Further studies are clearly needed, however, to dissect the mechanism of RST1 function and determine the point of action at which it regulates lipid biosynthesis.

Finally, our microarray analysis revealed another possible role for RST1 in ABA-associated defense response pathways. Of note, the rst1 mutant shows a 16-fold increase in transcription of the BG1 gene, a gene that encodes a glycosyl hydrolase known to cleave ABA from its glycosyl conjugate (Lee et al., 2006). Previous reports show that ABA affects plant defense responses negatively or positively depending on the plant-pathogen combination (Mauch-Mani and Mauch, 2005). ABA has been shown to suppress SA signaling (Audenaert et al., 2002; Mohr and Cahill, 2007), and antagonistic cross talk has been observed between SA- and ABA-mediated signaling in certain environmental stress responses (Yasuda et al., 2008). In addition, ENHANCED DISEASE RESISTANCE1-mediated resistance to powdery mildew is mediated, in part, by enhanced ABA signaling (Wawrzynska et al., 2008). As such, the down-regulation of SA synthesis in rst1 could be due to alterations in rst1's ABA levels. Further studies are thus needed to assess ABA amounts and other disease-associated ABA-related phenotypes in the rst1 mutant.

We report here the first plant mutant, to our knowledge, to exhibit resistance to necrotrophic pathogens but susceptibility to biotrophic pathogens, in contrast to previously reported mutants that exhibit increased susceptibility to necrotrophs but resistance to biotrophs (Veronese et al., 2006). RST1 modulates defense responses by affecting interactions between JA and SA synthesis and response pathways. Our findings here also implicate lipid pathways and ABA as players in RST1-mediated defense responses. Although the localization and bioinformatic analyses presented here indicate that RST1 is a plasma membrane-bound protein having 11 predicted transmembrane domains (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993), RST1 does not show significant identity to any protein of known function. Notwithstanding, the predicted three-dimensional protein structure of RST1 reveals similarity to the peroxisomal ATP-binding cassette transporter COMATOSE (CTS), a protein involved in JA synthesis via its role in transporting JA precursors into the peroxisomal lumen (Theodoulou et al., 2005). In contrast to rst1, the basal JA levels were greatly reduced in the cts mutant, and JA accumulates much less in response to wounding in cts plants compared with the wild type. If the RST1 protein is in fact a transporter similar to CTS, it is unclear why its deficiency would increase rather than decrease JA levels, as does a deficiency of CTS. Further studies are needed to shed light on the exact role of RST1 in the complex signaling networks leading to plant disease resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were grown on soilless medium (Metro-Mix200; Grace-Sierra) in growth chambers under a 12-h-light (23°C)/12-h-dark (22°C) or a 16-h-light (23°C)/8-h-dark (22°C) cycle at 70% relative humidity. Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and C24 were used as a wild type. The T-DNA insertion mutant rst1-1 (C24 background) was screened as described previously (Chen et al., 2005) and was selected from backcross populations to remove additional T-DNA inserts. rst1-2 and rst1-3 (Col-0 background) were obtained from the SALK T-DNA insertion collection at the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and had been backcrossed one time. rst1-2 and rst1-3 were crossed reciprocally. The pad4-1 line was described previously (Feys et al., 2005).

Pathogen Infections

Erysiphe cichoracearum strain UCSC1 was provided by Dr. Roger Innes (Indiana University, Bloomington). E. cichoracearum UCSC1 was maintained by inoculation of 4- or 5-week-old pad4-1 plants by tapping conidia from two or three infected leaves. Actively growing conidia (7–10 dpi) were used for inoculation of plants for experiments. Two methods of inoculation were used. High-density inoculations (20–50 conidia mm−2) were conducted by gently touching infected leaves to target plants. This method was used to determine disease resistance score with various ecotypes of Arabidopsis and in initial observation. Low-density inoculations were conducted with a modified settling tower (Adam and Somerville, 1996), a square metal tower 71 cm high covered with nylon mesh (40-μm openings) to break up the conidial chains. The more uniform low-density method was used for quantitative analysis of fungal development.

Cultures of Botrytis cinerea strain BO5-10 and Alternaria brassicicola strain MUCL 20297 were grown and disease assays were performed as described previously (Veronese et al., 2006). The bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato vir (Pst DC3000) and avr (Pst DC3000 avrRps4) were grown at 30°C on King's B agar plates or in liquid medium (King et al., 1954) containing 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and 50 μg mL−1 rifampicin. Cultured bacteria were resuspended in 10 mm MgCl2 and then adjusted to 1 × 105 colony-forming units mL−1. Suspended cells were infiltrated into leaves using a 1-mL syringe without a needle. Three leaf discs were collected from three independent samples and then ground in 10 mm MgCl2, serial diluted at 1:10, and plated on King's agar plates. Colonies were counted 48 h after incubation at 30°C.

Quantification of E. cichoracearum Growth

For quantitative analysis, the leaves were detached from 4- to 5-week-old plants grown in a growth chamber and placed on a 1.5% water agar plate with petioles embedded in the medium. The leaves could be sustained for at least 6 d under these conditions. The plates were inoculated using a settling tower as described above. The agar plates were placed in a Percival growth chamber at 20°C. High humidity was maintained by covering the plates with a plastic lid. The germination of spores was determined at 1 d after inoculation. Secondary hyphal length (4 d after inoculation) and conidiophore number (5 d after inoculation) were obtained from a minimum of six stained leaves from independent experiments. The number of conidiophores was counted per colony. Leaves were stained by boiling for 2 min in alcoholic lactophenol trypan blue (20 mL of ethanol, 10 mL of phenol, 10 mL of water, 10 mL of lactic acid, and 10 mg of trypan blue). The stained leaves were mounted under coverslips with 50% glycerol and examined using standard light microscopy images. Well-separated colonies in the central part of upper leaf surface were selected for analysis.

RNA Preparation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Two micrograms of total RNA was used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis with SuperScript II (Invitrogen) and an oligo(dT) primer. One microliter of cDNA was used as a template for the following primer sets: RST1-F (5′-TGGATGCCTACACTGTGGTT-3′), RST1-R (5′-GTACATGAGGAGAAGCGCAA-3′), PR1-F (5′-CATACACTCTGGTGGGCCTT-3′), PR1-R (5′-GACCACAAACTCCATTGCAC-3′), PR2-F (5′-ATCTCCCTTGCTCGTGAATC-3′), PR2-R (5′-TCGAGATTTGCGTCGAATAG-3′), PDF1.2-F (5′-GTTTGCGGAAACAGTAATGC-3′), PDF1.2-R (5′-CACACGATTTAGCACCAAAGA-3′), Tublin-F (5′-CGTGGATCACAGCAATACAGAGCC-3′), and Tublin-R (5′-CCTCCTGCACTTCCACTTCGTCTTC-3′). Gene-specific primers were designed using PrimerQuest (http://www.idtdna.com/Scitools/Applications/Primerquest/). Hairpin stability and compatibility were analyzed using OligoAnalyzer 3.0 (http://www.idtdna.com/analyzer/Applications/OligoAnalyzer/). The PCR products were 130 to 150 bp in length. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in 20-μL reactions containing 20 ng of template obtained from first-strand cDNA synthesis. Amounts were 0.3 μm each primer and 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen). The following PCR program was used to amplify: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s (denaturing), 58°C for 1 min (annealing), and 72°C for 1 min (extension). Primer efficiencies and relative expression levels were calculated using the comparative CT method (User Bulletin 2, ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System). 2−ΔΔCT values of control samples were normalized to 1.

Microarray Hybridization and Statistical Analysis

Total RNA (70 μg) was extracted from each sample using the Qiagen RNeasy Plant RNA Miniprep kit, RNA samples were reverse transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), and cDNAs were labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 by indirect labeling (Gong et al., 2005). Microarray slides over 26,000 probes (70-mer oligonucleotides) were used (http//ag.arizona.edu/microarray). To eliminate bias in the microarrays as a consequence of dye-related differences in labeling efficiency, dye labeling for each paired sample (mutant/wild type) was swapped. Three biological repeats were performed. Signal intensities were collected by GenePix 4000B (Axon Instruments), and images were analyzed using GenePix Pro 4.0. Lower intensities of the spots than background or with an aberrant spot shape were flagged by the GenePix software and confirmed manually, and original raw data of GPR files were analyzed by the TIGR-TM4 package (http://www.tm4.org; Saeed et al., 2003). Statistical analyses were performed using TM4-MEV (version 3.0.3). In MEV, a one-way t test with P = 0.01 was carried out to determine the different expression (mutant/wild type).

SA Measurements

Leaf tissues were collected from 4-week-old soil-grown plants. Tissue (0.3 g fresh weight) was extracted in 6 mL of ice-cold methanol for 24 h at 4°C and then in a solution of 3.6 mL of water plus 3 mL of chloroform with 20 μL of 5 mm 3,4,5-trimethoxy-trans-cinnamic acid (internal standard) for 24 h at 4°C. Supernatants were dried by speed vacuum. The residue was resuspended in 0.6 mL of ice-cold water:methanol (1:1, v/v), and SA was quantified by HPLC as described previously (Freeman et al., 2005).

Quantification of JA Levels

Leaf tissue (300 mg fresh weight per sample) was collected and immediately frozen at −80°C. The leaves were then extracted using 6 mL of cold methanol for 24 h at 4°C. At the time of methanol addition, 60 ng of dihydro-JA was added as an internal standard for quantitation. The methanol was separated from the plant tissue. The methanol solution was added to 3.6 mL of water and 3 mL of chloroform. After shaking, samples were allowed to sit for 24 h at 4°C. The supernatants were dried by speed vacuum. The residue was resuspended in 0.5 mL of an 80% methanol:20% water solution. The solution was centrifuged at 16,000g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new vessel and dried by speed vacuum. The remaining residue was redissolved in 50 μL of 50% mobile phase A and 50% mobile phase B prior to analysis by HPLC-mass spectrometry. Separations were performed on an Agilent 1100 system using a Waters Xterra MS C8 column (5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm). A binary mobile phase consisting of solvent systems A and B was used in gradient elution where A was 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in double distilled water and B was 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile. The mobile phase flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1. Initial conditions were set at 75:25 A:B with a linear gradient to 20:80 from 0 to 30 min. Gradient conditions were reset to 75:25 A:B from 30 to 32 min, then the column was equilibrated for 10 min at initial conditions prior to the next run. Following separation, the column effluent was introduced by negative mode electrospray ionization into an Agilent MSD-TOF spectrometer. Electrospray ionization capillary voltage was −3.5 kV, nitrogen gas temperature was set to 350°C, drying gas flow rate was 9.0 L min−1, nebulizer gas pressure was 35 psig, fragmentor voltage was 135 V, skimmer was 60 V, and octopole radio frequency was 250 V. Mass data (mass-to-charge ratio from 65 to 800) were collected and analyzed using Agilent MassHunter software. JA quantification was accomplished using a multilevel calibration curve.

Cutin Polyester Analysis

Leaf polyester content was analyzed on 20-d-old plants based on modification of depolymerization methods described previously (Bonaventure et al., 2004; Franke et al., 2005). Ground leaf tissues were delipidated in a Soxhlet extractor for 72 h with chloroform:methanol (1:1, v/v) containing 50 mg L−1 butylated hydroxytoluene. After delipidation, tissues were washed with methanol containing 50 mg L−1 butylated hydroxytoluene and dried in a vacuum desiccator for 4 d to 1 week before chemical analysis. Depolymerization reactions consisted of 6 mL of 3 n methanolic hydrochloride (Supelco) containing 0.45 mL (7%, v/v) of methyl acetate at 60°C. Methyl heptadecanoate was used as an internal standard. After 16 h, reactions were allowed to cool to room temperature and terminated by the addition of 6 mL of saturated, aqueous NaCl followed by two extractions (10 mL) with distilled dichloromethane to remove methyl ester monomers (Bonaventure et al., 2004). The organic phase was washed three times with 0.9% (w/v) aqueous NaCl, dried with 2,2-dimethoxypropane, and dried under nitrogen gas. Monomers were derivatized in pyridine and BSTFA (1:1, v/v) for 15 min at 100°C. Excess pyridine:BSTFA was removed with nitrogen gas, and the sample was dissolved in heptane:toluene (1:1, v/v) prior to analysis with a Hewlett-Packard 5890 series II gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and a 12-m, 0.2-mm i.d. HP-1 capillary column with helium as the carrier gas. The gas chromatograph was programmed with an initial temperature of 80°C and increased at 15°C min−1 to 200°C, then increased at 2°C min−1 to 280°C. Quantification was based on uncorrected flame ionization detection peak areas relative to the internal standard methyl heptadecanoate peak area. Areas of rosette leaves were determined by ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) using digital images of flattened leaves. Cutin data were analyzed using SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute). Student's t tests were used to detect significant differences between cutin monomer means. Five replicates of each line were used for leaf cutin monomer analysis, and α was set at 0.05.

Generation of RST1 Overexpression and Complemented Transgenic Plants

To generate the CaMV 35Spro:RST1 construct, RST1 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR with primer sets (including an XbaI restriction site [boldface] in the first part of the forward primer) F (5′-GCTCTAGATTGGGCCAAATCGGACGGC-3′) and R (5′-GTGGCGACAATTTAAGGAG-3′) for the first part and F2 (5′-GACCTTTCAGCGTCCGGCG-3′) and R2 (5′-GGCTACTATGTCGATGTACC-3′) for the second fragment. Two fragments were amplified, as few applicable multiple cloning sites were present in the binary vector pCAMBIA99-1 (a pCAMBIA 1200-based vector containing modified enzyme sites). The first fragment (3,858 bp) consists of the 50 bp from the start codon to about 50 bp downstream of the PstI site in the middle of the RST1 genomic sequence. The second part (4,410 bp) consists of about 30 bp upstream of PstI to about 100 bp downstream of the stop codon. Amplified PCR fragments were subcloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Subcloned first and second fragments in T Easy vector were digested by XbaI and PstI or by PstI and EcoRI, respectively, and then two fragments were subcloned into pCAMBIA99-1 between the XbaI and EcoRI sites. The construct was introduced into rst1-2, rst1-3, and wild-type Col-0 using an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated (strain GV3101) floral dipping transformation method (Clough and Bent, 1998).

Construction of the RST1 Promoter:GUS Reporter and GUS Activity Assay

To generate RST1 promoter:GUS, a 1,200-bp upstream region including the initiation codon of RST1 was amplified by PCR with the following primers containing BamHI and SpeI restriction sites: 5′-GAATTCCGCGGCCCCTCCACTAACC-3′ and 5′-CCATGGCGTATGAGGCCATCGCTTTGG-3′, respectively. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and SpeI and subcloned at BamHI and SpeI sites of the pCAMBIA 1303 vector, which harbors GUS and GFP reporter genes. The RST1pro:GUS:GFP clone, along with a 35Spro:GUS:GFP control, were transformed into Arabidopsis Col-0 using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Various developmental stages of transgenic plants were incubated overnight in 1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (Rose Scientific) and 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5 with 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100). Chlorophyll was removed by washing samples two to three times with 70% (v/v) ethanol. Samples were monitored and captured using a Nikon E 800 microscope.

Subcellular Localization of RST1

To generate CaMV 35Spro:RST1:GFP, the full-length RST1 open reading frame without stop codon was synthesized with the following primer set including XhoI and SpeI restriction sites: F (5′-CTCGAGATGGCCTCATACGCTACG-3′) and R (5′-ACTAGTAGACATGTCCATAGAAGCAA-3′), respectively. The PCR products were subcloned in pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), digested with XhoI, produced as a blunted end using Klenow fragment polymerase (Roche), and then digested with SpeI. The fragment including a 5′ blunted end and a 3′ cohesive end was subcloned in frame with pCAMBIA 1302 prepared as an insert fragment except using NcoI instead of XhoI. Plasmids were purified using the Qiagen Plasmid Mini Purification kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The plasmids were introduced into rst1-2. Five rescued plants in the T3 generation were screened from the rst1-2 background. Plants were grown on a Murashige and Skoog solid plate for 3 to 4 d. Images were taken using a Radiance 2100 MP Rainbow (Bio-Rad) on a TE2000 (Nikon) inverted microscope using a 60 × 1.4 numerical aperture lens. The 488-nm line of the four-line argon laser (National Laser) was used to excite the GFP, and the fluorescence emitted between 500 and 540 nm was collected. The transformants in the Col-0 background were confirmed as controls.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number AY307371.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Characterization of rst1 mutations and the predicted structure of the RST1 protein.

Supplemental Figure S2. Response of Arabidopsis wild-type C24 and the rst1-1 mutant to E. cichoracearum inoculation.

Supplemental Figure S3. Transpiration rate in the dark of wild-type Col-0, rst1-2, and pad 4-1.

Supplemental Figure S4. Sensitivity of Col-0, rst1-3, pad4-1, and C24 plants to BASTA.

Supplemental Figure S5. Permeability assay on leaf cuticles of wild-type Col-0, rst1-2, rst1-3, pad4-1, and lacs2-3.

Supplemental Figure S6. The rst1 mutants show slightly high basal expression of PR1 and PR2.

Supplemental Figure S7. The rst1 mutants show higher basal expression of BG1 (At1g52400), CHITINASE (At2g43570), and ATHILA RETROELEMENT (At5g32475).

Supplemental Figure S8. The rst1 mutants display normal bacterial growth after inoculation with Pst strains DC3000 and DC3000 expressing avrRps4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shisong Ma and Dong-ha Oh for statistical data analyses. We thank Dr. David Salt's laboratory for help with the SA assay and Dr. Roger Innes for providing E. cichoracearum strain UCSC1. We also thank the World Class University Program (R32-10148) of the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology in Korea for their support. Lastly, we thank the SALK Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory and the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA mutants (SALK 070359 and 129280).

This work was supported by the National Research Initiative of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (grant no. 2006–35304–17323).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Matthew A. Jenks (jenksm@purdue.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Adam L, Somerville SC (1996) Genetic characterization of five powdery mildew disease resistance loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 9 341–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR (1999) EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284 2148–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenaert K, De Meyer GB, Hofte MM (2002) Abscisic acid determines basal susceptibility of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and suppresses salicylic acid-dependent signaling mechanisms. Plant Physiol 128 491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessire M, Chassot C, Jacquat AC, Humphry M, Borel S, Petéot J, Méraux JP, Nawrath C (2007) A permeable cuticle in Arabidopsis leads to a strong resistance to Botrytis cinerea. EMBO J 26 2158–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman S, Staal J, Thomma BP, Wang M, Dixelius C (2004) Characterization of an Arabidopsis-Leptosphaeria maculans pathosystem: resistance partially requires camalexin biosynthesis and is independent of salicylic acid, ethylene and jasmonic acid signalling. Plant J 37 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventure G, Beisson F, Ohlrogge J, Pollard M (2004) Analysis of the aliphatic monomer composition of polyesters associated with Arabidopsis epidermis: occurrence of octadeca-cis-6, cis-9-diene-1,18-dioate as the major component. Plant J 40 920–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Glazebrook J, Clarke JD, Volko S, Dong X (1997) The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene that controls systemic acquired resistance encodes a novel protein containing ankyrin repeats. Cell 88 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra-Shekara AC, Venugopal SC, Barman SR, Kachroo A, Kachroo P (2007) Plastidial fatty acid levels regulate resistance gene-dependent defense signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 7277–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassot C, Métraux JP (2005) The cuticle as source of signal for plant defense. Plant Biosyst 139 28–31 [Google Scholar]

- Chassot C, Nawrath C, Métraux JP (2007) Cuticular defects lead to full immunity to a major plant pathogen. Plant J 49 972–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi R, Krothapalli K, Makandar R, Nandi A, Sparks AA, Roth MR, Welti R, Shah J (2008) Plastid ω3-fatty acid desaturase-dependent accumulation of a systemic acquired resistance inducing activity in petiole exudates of Arabidopsis thaliana is independent of jasmonic acid. Plant J 54 106–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Goodwin SM, Liu X, Bressan RA, Jenks MA (2005) Mutation of the RESURRECTION1 locus of Arabidopsis reveals an association of cuticular wax with embryo development 1. Plant Physiol 139 909–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coego A, Ramirez V, Gil MJ, Flors V, Mauch-Mani B, Vera P (2005) An Arabidopsis homeodomain transcription factor, OVEREXPRESSOR OF CATIONIC PEROXIDASE 3, mediates resistance to infection by necrotrophic pathogens. Plant Cell 17 2123–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JD (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewdney J, Reuber TL, Wildermuth MC, Devoto A, Cui J, Stutius LM, Drummond EP, Ausubel FM (2000) Three unique mutants of Arabidopsis identify eds loci required for limiting growth of a biotrophic fungal pathogen. Plant J 24 205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan R, Luo H, Foerster AM, Abuqamar S, Du HN, Briggs SD, Mittelsten Scheid O, Mengiste T (2009) HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION1 interacts with a subunit of the mediator complex and regulates defense against necrotrophic fungal pathogens in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 1000–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J, ten Have A, van Kan JAL (2002) The role of ethylene and wound signaling in resistance of tomato to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 129 1341–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doares SH, Narvaez-Vasquez J, Conconi A, Ryan CA (1995) Salicylic acid inhibits synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in tomato leaves induced by systemin and jasmonic acid. Plant Physiol 108 1741–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi AJ, Yalpani N, Silverman P, Raskin I (1992) Localization, conjugation, and function of salicylic acid in tobacco during the hypersensitive reaction to tobacco mosaic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 2480–2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple P, Apel K, Bohlmann H (1995) An Arabidopsis thaliana thionin gene is inducible via a signal transduction pathway different from that for pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Physiol 109 813–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple P, Mack AA, Morris VR, Dangl JL (2003) Antagonistic control of oxidative stress-induced cell death in Arabidopsis by two related, plant-specific zinc finger proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 6831–6836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth M, Schweizer P, Buchala A, Markstadter C, Riederer M, Kato T, Kauss H (1998) Cutin monomers and surface wax constituents elicit H2O2 in conditioned cucumber hypocotyl segments and enhance the activity of other H2O2 elicitors. Plant Physiol 117 1373–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Galletti R, Denoux C, De Lorenzo G, Ausubel FM, Dewdney J (2007) Resistance to Botrytis cinerea induced in Arabidopsis by elicitors is independent of salicylic acid, ethylene, or jasmonate signaling but requires PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT3. Plant Physiol 144 367–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Plotnikova JM, De Lorenzo G, Ausubel FM (2003) Arabidopsis local resistance to Botrytis cinerea involves salicylic acid and camalexin and requires EDS4 and PAD2, but not SID2, EDS5 or PAD4. Plant J 35 193–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJ, Moisan LJ, Newman MA, Parker JE (2001) Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. EMBO J 20 5400–5411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJ, Wiermer M, Bhat RA, Moisan LJ, Medina-Escobar N, Neu C, Cabral A, Parker JE (2005) Arabidopsis SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE101 stabilizes and signals within an ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 complex in plant innate immunity. Plant Cell 17 2601–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJF, Benedetti CE, Penfold CN, Turner JG (1994) Arabidopsis mutants selected for resistance to the phytotoxin coronatine are male sterile, insensitive to methyl jasmonate, and resistant to a bacterial pathogen. Plant Cell 6 751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig A, Mayfield JA, Miley NL, Chau S, Fischer RL, Preuss D (2000) Alterations in CER6, a gene identical to CUT1, differentially affect long-chain lipid content on the surface of pollen and stems. Plant Cell 12 2001–2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SA, Dewey FM, Gurr SJ (1996) The role of cutinase in germling development and infection by Erysiphe graminis f. sp. hordei. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 49 201–211 [Google Scholar]

- Franke R, Briesen I, Wojciechowski T, Faust A, Yephremov A, Nawrath C, Schreiber L (2005) Apoplastic polyesters in Arabidopsis surface tissues: a typical suberin and a particular cutin. Phytochemistry 66 2643–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JL, Garcia D, Kim D, Hopf A, Salt DE (2005) Constitutively elevated salicylic acid signals glutathione-mediated nickel tolerance in Thlaspi nickel hyperaccumulators 1. Plant Physiol 137 1082–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fric F, Wolf G (1994) Hydrolytic enzymes of ungerminated and germinated conidia of Erysiphe graminis DC. f.sp. hordei Marchal. J Phytopathol 140 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooij B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J (1993) Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 261 754–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbay B, Tautu MT, Costaglioli P (2007) Low level of pathogenesis-related protein 1 mRNA expression in 15-day-old Arabidopsis cer6-2 and cer2 eceriferum mutants. Plant Sci 172 299–305 [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert RD, Johnson AM, Dean RA (1996) Chemical signals responsible for appressorium formation in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 48 335–346 [Google Scholar]

- Gong Q, Li P, Ma S, Indu Rupassara S, Bohnert HJ (2005) Salinity stress adaptation competence in the extremophile Thellungiella halophila in comparison with its relative Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 44 826–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SM, Jenks MA (2005) Plant cuticle function as a barrier to water loss. In MA Janks, PM Hasegawa, eds, Plant Abiotic Stress. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp 14–36

- Gupta V, Willits MG, Glazebrook J (2000) Arabidopsis thaliana EDS4 contributes to salicylic acid (SA)-dependent expression of defense responses: evidence for inhibition of jasmonic acid signaling by SA. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Stoffel W (1993) TMbase: a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 374 166 [Google Scholar]

- Jenks MA, Joly RJ, Peters PJ, Rich PJ, Axtell JD, Ashworth EN (1994) Chemically induced cuticle mutation affecting epidermal conductance to water vapor and disease susceptibility in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Plant Physiol 105 1239–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo P, Kachroo A, Lapchyk L, Hildebrand D, Klessig DF (2003. a) Restoration of defective cross talk in ssi2 mutants: role of salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, and fatty acids in SSI2-mediated signaling. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16 1022–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo A, Lapchyk L, Fukushige H, Hildebrand D, Klessig D, Kachroo P (2003. b) Plastidial fatty acid signaling modulates salicylic acid- and jasmonic acid-mediated defense pathways in the Arabidopsis ssi2 mutant. Plant Cell 15 2952–2965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo P, Shanklin J, Shah J, Whittle EJ, Klessig DF (2001) A fatty acid desaturase modulates the activation of defense signaling pathways in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 9448–9453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE (1954) Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med 44 301–307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel BN, Brooks DM (2002) Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyukov S, Faust A, Nawrath CBS, Voisin D, Efremova N, Franke R, Schreiber L, Saedler H, Méraux JP (2006) The epidermis-specific extracellular BODYGUARD controls cuticle development and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 321–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Nam J, Park HC, Na G, Miura K, Jin JB, Yoo CY, Baek D, Kim DH, Jeong JC (2007) Salicylic acid-mediated innate immunity in Arabidopsis is regulated by SIZ1 SUMO E3 ligase. Plant J 49 79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Piao HL, Kim HY, Choi SM, Jiang F, Hartung W, Hwang I, Kwak JM, Lee IJ (2006) Activation of glucosidase via stress-induced polymerization rapidly increases active pools of abscisic acid. Cell 126 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DX, Sirakova T, Rogers L, Ettinger WF, Kolattukudy PE (2002) Regulation of constitutively expressed and induced cutinase genes by different zinc finger transcription factors in Fusarium solani f. sp. pisi (Nectria haematococca). J Biol Chem 277 7905–7912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TS, Kolattukudy PE (1978) Induction of a polyester hydrolase (cutinase) by low levels of cutin monomers in Fusarium solani f.sp. pisi. J Bacteriol 133 942–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loake G, Grant M (2007) Salicylic acid in plant defence: the players and protagonists. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10 466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J, Carr JP, Klessig DF, Raskin I (1990) Salicylic acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science 250 1002–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J, Hennig J, Klessig DF (1992) Temperature-dependent induction of salicylic acid and its conjugates during the resistance response to tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Cell 4 359–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch-Mani B, Mauch F (2005) The role of abscisic acid in plant-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8 409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConn M, Creelman RA, Bell E, Mullet JE (1997) Jasmonate is essential for insect defense in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 5473–5477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métraux JP, Signer H, Ryals J, Ward E, Wyss-Benz M, Gaudin J, Raschdorf K, Schmid E, Blum W, Inverardi B (1990) Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science 250 1004–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr PG, Cahill DM (2007) Suppression by ABA of salicylic acid and lignin accumulation and the expression of multiple genes, in Arabidopsis infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Funct Integr Genomics 7 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Moeder W, Kachroo P, Klessig DF, Shah J (2005) Arabidopsis ssi2-conferred susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea is dependent on EDS5 and PAD4. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18 363–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C (2002) The biopolymers cutin and suberin. In CR Somerville, EM Meyerowitz, eds, The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, doi/, http://www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nawrath C (2006) Unraveling the complex network of cuticular structure and function. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson RL, Kunoh H (1994) Early interactions, adhesion, and establishment of the infection court by Erysiphe graminis. Can J Bot 73 S609–S615 [Google Scholar]