Abstract

In fiscal 2002, Delaware replaced traditional cost-reimbursement contracts with performance-based contracts for all outpatient addiction treatment programs. Incentives included 90% capacity utilization and active patient participation in treatment.

One of the programs failed to meet requirements. Strategies adopted by successful programs included extended hours of operation, facility enhancements, salary incentives for counselors, and two evidence-based therapies (MI and CBT). Average capacity utilization from 2001 to 2006 went from 54% to 95%; and the average proportion of patients’ meeting participation requirements went from 53% to 70%—with no notable changes in the patient population.

We conclude that properly designed, program-based contract incentives are feasible to apply, welcomed by programs and may help set the financial conditions necessary to implement other evidence-based clinical efforts; toward the overall goal of improving addiction treatment.

Keywords: Addiction treatment, Pay for performance, Evidence-based practices

1. Introduction

1.1. Patient contingencies and incentives in addiction treatment

There is now a compelling research literature showing the value of various types of behavioral contingencies coupled with reinforcement in the rehabilitation of addicted patients [1,2]. Behavioral contingencies coupled with various types of incentives have been effective in reducing cocaine positive urines [3,4], increasing likelihood of employment and housing among methadone-maintained patients [5,6], and improving marital relationships among alcohol-dependent couples [7]. The demonstrated impact of behavioral contingencies on patient-level performance leads to the question of whether such contingencies might also be useful in improving program or provider-level performance?

1.2. Provider contingencies in healthcare

At this writing, 29 state Medicaid offices have applied some types of state-level “pay for performance,” “value-based purchasing” or “performance contracting” contingency in their contracts with managed care organizations (n = 20), primary care physicians (n = 6) or nursing homes (n=3) [8]. An example of a typical performance contracting effort would be an end-of-year bonus for primary care physicians when 80% or more of their diabetes patients have had retinal examinations or have hemoglobin A1c (marker of diabetes severity) levels below an agreed upon threshold [8]. Most of these types of performance contracting efforts have been directed toward better management of common, expensive chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma and cardiovascular illness; and most have focused upon the performance of an individual physician [9–11]. While these provider or manager-based incentives for improved healthcare processes or better during-treatment outcomes have not all been successful [9], a 2006 poll showed that 85% of state Medicaid agencies planned to adopt new incentive-based contracts in the near future [8].

A notable exception to this trend is the treatment of addiction; only two states have used incentives to manage behavioral health problems and only one (Maine) has published a study of program-based payments contingent upon better patient-level results in the treatment of addiction [12]. From 1992 through 1995, the Maine Office of Substance Abuse changed its fee-for-service contracting procedure to provide financial penalties for all residential and outpatient programs whose patients failed to meet pre-negotiated threshold levels on twelve commonly used effectiveness measures such as abstinence, employment and no arrests. Two additional measures of program efficiency (e.g. number of clients served and number of services per client) were also part of the overall contingency contract. The effectiveness measures were collected and reported by program personnel from patients’ self-report at the time of treatment discharge. Though some rewards for better performance were made available (e.g. additional monies from block grant funds), the majority of the effort was directed at identifying and motivating programs with poor performance to change that performance. This was done through state meetings with identified poor performers, adding requirements for revised clinical procedures to a contract, or reducing a contract period from one year to six months.

The proportion of patients in the system who met minimal or better performance threshold levels across all the effectiveness measures, was tracked using the reported records from the programs to the state office from 1990 (two years prior to the performance contract) through 1994 (two years into contract change). This measure showed a significant positive change – in both outpatient and residential programs – from approximately 20% to about 45% achievement of performance threshold over the four-year period. There was a comparable increase over time in the efficiency measures as well. Time in treatment across both modalities changed from an average of 48 to 61 days over this period [12].

The authors used regression analysis to test the possibility that the favorable performance was due to a change in other program behaviors such as the new requirement to report outcomes; or to a change in patient characteristics. After adjusting for these other variables the authors still concluded that the state performance contracting was responsible for the improved efficiency and effectiveness at a rate of about 2% per quarter. Importantly, and consistent with their interpretation, the data showed that those programs with the greatest proportion of state contracting showed the largest performance increases over time. These favorable results were tempered by a subsequent report showing that over the course of the performance contracting, state providers were less likely to admit more severely affected patients [13].

1.3. Performance-based contracting in Delaware

In this context, the present paper describes an unusual and innovative effort by the Delaware Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health (DSAMH) to improve the accountability and effectiveness of clinical services for publicly served alcohol and other drug-dependent patients. The outpatient treatment providers in Delaware were eligible to receive financial bonuses contingent upon their ability to attract and engage their full complement of patients (i.e. capacity utilization) and to keep those patients actively engaged in all phases of that outpatient treatment. The mechanism by which they applied these behavioral contingencies was a standard performance contract between the agency and the treatment providers.

There were significant differences between the contingency contracting methods used by Delaware and by Maine. Specifically, only outpatient treatment programs were part of the performance contracting study in Delaware. The Delaware contract used both positive incentives (additional dollars) and penalties (loss of base dollars). Importantly, earned incentives were provided on a monthly basis as part of regular billing. Maine used 12 post-treatment patient measures as the performance thresholds; and these were self-report measures by the programs. Delaware used just three performance criteria, measured during-treatment, and they were verifiable, not purely self-report.

As evaluators of many types of addiction treatment interventions and programs, our group of researchers at the Treatment Research Institute found this approach to be quite novel and worthy of examination for several reasons. First, despite offering many trainings in various types of evidence-based clinical practices, DSAMH had had, at best, mixed success in getting the providers to adopt and sustain any of the newer evidence-based practices. We wondered whether financial incentives for better “program performance” might offer the conditions under which the adoption of new evidence-based therapies might be feasible and indeed a good business investment.

Another reason for our interest was that the actual performance-based contract language established a local standard of evidence (capacity utilization and patient participation) and encouraged programs to try combinations of research derived and locally developed practices to achieve that standard. We wondered which kind of interventions under these real world circumstances would produce “evidence” of improved patient engagement and participation; and the associated financial rewards. This is what Miller has called “practice-based evidence” [14]. Finally, given some of the negative side effects of “pay for performance” in the general healthcare field [9] and the adverse patient selection finding in the Maine study [13], we wondered whether and how the pressure for improved performance might lead to unforeseen negative results.

It should be noted at the outset that this state-wide experiment was locally created and implemented without funding for a systematic, concurrent evaluation. For these reasons, and like the Maine study, the information available for the evaluation consisted entirely of state records of program utilization and payments, prior to, during and following implementation of the performance contracting. Moreover, because the project was implemented in all outpatient treatment programs, there is no comparison group of programs that were not subjected to the performance contracting. Despite these limitations, the “realworld” context of this project coupled with the timely nature of the topic and issues offer a unique opportunity to examine performance contracting in a state addiction system.

To these ends, this paper first discusses the rationale and background for the performance contracting. The next part describes some of the clinical and programmatic adaptations by the providers to the terms of the new contract. The last part of the paper presents analyses of state-wide performance on the two major criteria (capacity utilization and active patient participation) throughout the six years of the performance contracting.

2. Part 1—Rationale and background for the performance contracting experiment

Like other Substance Abuse Single State Agencies, DSAMH licenses and monitors, funds, provides training and technical assistance, and oversees an array of services that include detoxification, outpatient, residential and methadone treatment programs across the State of Delaware. In this paper, we focus upon contracts with the five outpatient treatment provider organizations that operated all eleven outpatient programs in the state. All organizations were community-based and had longstanding contractual relationships with DSAMH for the provision of substance abuse treatment services to primarily lower socioeconomic status clients throughout the state.

Virtually all of the prior contracts negotiated between DSAMH and addiction treatment provider organizations had been cost-reimbursement or fee-for-service contracts based on the costs associated with the provision of a specified (by DSAMH) level of treatment services (e.g. outpatient, residential, etc.). This type of conventional contracting had no provision to reward programs with better performance or to penalize those with poor performance. In order to attain greater accountability and better clinical management, DSAMH looked to other governmental precedents for connecting payment to performance. For example, Transportation Departments frequently use payment incentives in contracts for roadwork. In those contracts, it is typical to provide financial rewards for completion ahead of schedule and penalties for failing to meet deadlines. Those contracts typically set specific standards for construction methods that the contractors must adhere to, as well as a clear indication of how the finished road will function. However, those contracts typically allow significant latitude in the construction methods actually used—to foster ingenuity and creativity among those who do this work as a profession. A key element in fostering creativity, ingenuity, and efficiency is that these contracts provide incentives for faster completion and/or for a better finished product—and penalties for poor performance.

That same thinking was applied to the purchase of the addiction treatment services in Delaware beginning in 2002. The standard requirements in the 2002 contract included core services commonly accepted as necessary for adequate care of public sector addiction clients such as the use of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [15–17] as an assessment; the provision of group, individual and family counseling; screening and referral for HIV, other infectious diseases and mental illnesses; and evidence of cultural competence in the delivery of those services. In addition, contracted providers were asked to identify at least one evidence-based practice and to provide evidence of their ability to perform that practice. Most providers chose Motivational Interviewing [18] and/or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [19]. Beyond these basic elements the overall intent was to provide significant latitude for the providers to determine how they would go about organizing and delivering services to meet the new performance criteria (see below). Importantly, there were significant financial incentives for meeting or exceeding each of these targets and financial penalties for failing to meet them.

2.1. Selecting and detailing performance criteria

With these general principles as the foundation for the initiative, three patient behaviors were selected as the key performance criteria: (1) capacity utilization, (2) active participation and (3) program completion.

2.2. Capacity utilization

Utilization represents the most important and basic indication of a program’s ability to attract addicted patients into treatment. It was operationally defined as admission into the outpatient program. Program capacity was negotiated individually with each program based upon consideration of their organizational capacity, the primary geographical area they would serve, and their annual costs of program operation at full utilization. From the outset all programs were required to accept all patients who sought admission and met eligibility criteria. In fiscal 2002, the first year of implementation, programs were required to maintain an 80% utilization rate each month to earn their base payment for the month. After 2002, the utilization rate was increased to 90%.

In practice, DSAMH agreed to pay one-twelfth of the total annual operating costs for a program at the end of each month, contingent upon that program successfully maintaining an 80% rate of their utilization capacity on that month. Utilization rates of 70–79% for the month received 90% of full payment; 60–69% utilization received 70%; and utilization rates below 60% received only 50% of their monthly allocation. Because utilization was considered key to the general effort to improve the accountability and performance of the treatment system, the remaining criteria (see below) were only applicable if the utilization rate was at or above the target level—no other incentives could be earned if program utilization was below 80% and later 90% target rate.

2.3. Active participation in treatment

A second performance criterion for all outpatient programs was the ability to engage admitted patients into adequate levels of participation in the clinical activities they offered. This aspect of performance was also considered a fundamental part of care and management of addicted patients, well justified in the outcomes literature [20–23]. It was recognized that patients would need to have more intensive participation in the early stages of their outpatient care than at later times. Thus, a tiered system of participation intensity was agreed upon by DSAMH and all programs in the system (see Table 1). It is important to note that this criterion was not explicitly designed simply to reward greater lengths of stay—but rather, greater rates of performance among patients at each phase of their treatment.

Table 1.

Schedule of participation and bonus rates

| Treatment phase | Time in treatment (days) | Expected attendance | Compensation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | ≤30 | 2 sessions per week | 1 |

| Phase 2 | 31–90 | 4 sessions per month | 1 |

| Phase 3 | 91–180 | 4 sessions per month | 1 |

| Phase 4 | >180 | 2 sessions per month | 1 |

| Bonus for achieving all four targets | 1 |

For example, the expected participation rate for a patient in the first month of care (Phase 1: 1–30 days) was two group or individual sessions per week, whereas the expected level of participation for patients in the final tier (Phase 4: >180 days) was two sessions per month. Again using the individually negotiated costs of care for each program – and first contingent upon meeting the capacity utilization target – programs could earn an additional 1% for each of four participation targets met. If programs met all four participation criteria, the program received an additional 1% bonus. In practice, this was calculated in a three-step formula each month:

Length of time in treatment: Determine for each patient, the length of time that the client had been enrolled in treatment: 1–30 days; 31–90 days; 91–180 days; and 180+ days.

Attendance at treatment sessions: Determine for each patient, whether they had met the attendance minimums for that phase of treatment.

Incentive targets met: For each of the four phases of treatment, calculate the percentage of eligible clients who met the attendance minimums for that phase. The threshold performance levels were 50% for 1–30 days; 60% for 31–90 days; 70% for 91–180 days; and 80% for 180+ days. Thus, on a monthly basis, based on this formula, programs that met all the active participation targets could earn up to 5% above their base rate payment for that month.

2.4. Program completion

The third incentive payment was tied to successful completion of the program, operationally defined as active participation in treatment for a minimum of 60 days, achievement of the major goals of his/her treatment plan; and submitting a minimum of four consecutive weekly urine samples that were free from illegal drugs and alcohol. Providers could earn US$ 100 for each client that completed the program in accordance with those criteria. Due to a combination of funding restrictions and the fact that most programs rapidly improved their performance on this criterion, funding for this criterion was set to a yearly maximum for each program. In fact, almost all programs achieved that maximum prior to the end of each fiscal year. We do not report further on this criterion.

3. Part 2—Helping programs adapt to the contingencies

Because the performance-based contracting introduced a major systemic change, DSAMH offered three types of assistance at the beginning of the new contract period: a trial period, cooperative meetings, and training on evidence-based practices.

The first six months following the implementation of the performance incentives in fiscal 2002 were considered a “hold harmless” period where programs were expected to try procedures that would increase utilization and active participation, but all programs received full payment of one-twelfth of their annual budget—though not performance incentives. During this time period, DSAMH hosted regular provider meetings to encourage sharing of their strategies for improving utilization and patient attendance. These meetings gradually produced a closer partnership between the state and providers, and among providers themselves. The meetings encouraged providers to share successes and failures, good ideas and emerging practices. The meetings also identified some state mandated procedures that were barriers to the new approach, leading to change or removal of the procedures.

Concurrent with program experimentation during this six-month period, DSAMH worked on improving data collection procedures for the key criteria, developed auditing procedures and streamlining the payment reimbursement procedures. Finally, DSAMH offered clinical training in Motivational Interviewing [18] and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [19] since programs felt these might help them meet their goals.

4. Part 3—Changes in program and patient behaviors

4.1. Program adaptation

Two important characteristics of this experiment bear re-emphasis. First, DSAMH structured the contingencies to foster inter-program collaboration and exchange of ideas. Second, while DSAMH did require a core set of basic services, they did not force programs to use any particular technique or specified set of clinical procedures to achieve the performance targets. This was widely appreciated by the programs that considered it respectful of their judgment, responsibility and clinical expertise. The result was a situation where innovation, creativity and collaboration were rewarded and the procedures developed from this “practice-based evidence” are among the most important interim products of the experiment.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to fully describe all the clinical and administrative strategies that were tried by the programs. Also, there was not a formal qualitative evaluation of these program-level responses. However, multiple interviews and meetings with the providers and DSAMH officials over the years suggest several “best practices” that were widely adopted in response to the new contract. First, efforts were made to make access and participation by the patients easier and more engaging. All programs streamlined their admission procedures, reducing the data collection burden and focusing early sessions upon meeting the patients’ needs and promoting engagement. All programs increased their hours of operation making it easier for patients to attend sessions in the morning and evening. Three programs opened additional satellite offices to make services more easily accessible in previously under-served areas. Several programs made physical changes in their programs to make them more attractive and inviting. Four programs developed methods of sharing the program performance bonuses directly with the clinical staff. Some tied patient performance bonuses directly to the salaries of their counselors, while other programs created group incentives based on the performance of the clinical teams. Finally, all programs learned at least one evidence-based clinical practice—primarily Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

4.2. Patient behavior changes

4.2.1. Capacity utilization

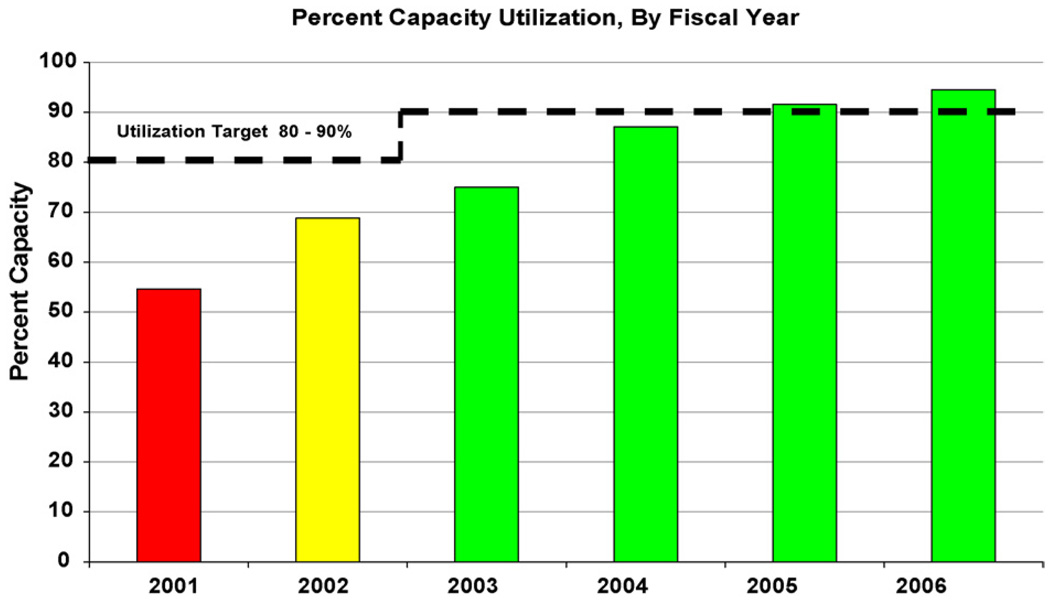

Fig. 1 shows the mean percent of total outpatient addiction treatment capacity utilization in the state of Delaware prior to the performance contracting and throughout the following five fiscal years. (Note: Contract requirements were only enforced during the last six months of fiscal 2002; and the target capacity threshold was changed to 90% in 2003.) As can be seen, there was an immediate, significant and continuing improvement in capacity utilization from 54% in 2001 to 95% utilization by 2006.

Fig. 1.

Shows the mean percent of total outpatient addiction treatment capacity in Delaware, by year.

As part of the evaluation we wondered whether the utilization targets were achieved by simply reducing system capacity. In this regard, Table 2 illustrates some of the specifics of the growth in capacity utilization over the years. As can be seen, in 2001 there were five provider organizations each operating a single outpatient program with a total system capacity of 860 slots. On an average month in 2001 only about 464 patients (54% of 860) were engaged in treatment.

Table 2.

Outpatient system capacity and utilization, by provider and year

| 2001 capacity | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2006 capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider 1 | 175 | 43% | 51% | |||||

| Provider 2 | 125 | 69% | 94% | 87% | 89% | 91% | 107% | 130 |

| Provider 2a | 61% | 92% | 98% | 89% | 60 | |||

| Provider 3 | 135 | 48% | 56% | 89% | 88% | 89% | 90% | 130 |

| Provider 3a | 65% | 90% | 92% | 90% | 110 | |||

| Provider 4 | 125 | 47% | 64% | 82% | 83% | 82% | 83% | 125 |

| Provider 5 | 300 | 66% | 79% | 90% | 88% | 90% | 92% | 300 |

| Provider 5a | 51% | 80% | 99% | 111% | 60 | |||

| 860 | 54% | 69% | 75% | 87% | 92% | 95% | 915 |

Table shows increased system capacity through the creation of additional treatment programs (2a, 3a and 5a), and improved utilization by all but one program (1) during the course of performance-based contracting.

Two changes took place over the ensuing five years. First, Program 1 was unable to meet its utilization target and voluntarily withdrew from the contract by the beginning of fiscal year 2003. In response, two other providers opened additional program sites in the Program 1 region (Table 2, Providers 2a and 3a). Provider 5 also opened an additional program (5a) in a separate area to meet expected demand. As can be seen, each of these new programs achieved their performance targets within two years. Thus, by 2006, on an average month, there were approximately 869 patients in treatment (95% of 915)—an increase of 87%.

4.2.2. Changes in patient characteristics over time

One evaluation question that arises from these data and from the results of the prior Maine study [13] is whether there were changes in patient admission characteristics over time due to the performance contracting. Specifically, we wondered whether the programs had changed admission practices in an effort to attract less severe and better socially supported patients who might be more likely to remain in treatment and be more compliant with the attendance regimen.

We only had limited information on demographic and treatment history information on admissions prior to the start of the performance contracting, as standard reporting was not well systematized at that point and computer records were less available. However, admission records were available on all admissions to seven programs (no data were obtained from Provider 1 after the first year), from fiscal 2002 through 2006. Table 3 shows patient characteristics averaged across those programs over the five-year period, since no significant differences in these trends were found in individual program analyses.

Table 3.

Patient demographics and characteristics across years

| Fiscal year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 (N= 1204) | 2003 (N= 2227) | 2004 (N= 2121) | 2005 (N= 2004) | 2006 (N= 2099) | |

| New admissions (%) | 90 | 85 | 81 | 79 | 77 |

| Gender (% male) | 80 | 78 | 77 | 78 | 75 |

| Mean age (S.D.) | 33.0 (10.7) | 32.8 (9.9) | 33.1 (10.3) | 33.6 (10.5) | 34.0 (10.7) |

| Race (%) | |||||

| Caucasian | 56 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 56 |

| African-American | 41 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| Other minority | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Employed (% employed) | 57 | 55 | 55 | 54 | 52 |

| Reported mental illness | 12 | 13 | 14 | 20 | 23 |

| History of substance abuse treatment | 67 | 70 | 65 | 67 | 68 |

| Primary substance of abuse (%) | |||||

| Alcohol | 35 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 33 |

| Cocaine | 22 | 23 | 19 | 20 | 22 |

| Marijuana | 34 | 33 | 31 | 30 | 32 |

| Legal involvement (%) | |||||

| None current | 18 | 16 | 25 | 23 | 28 |

| Awaiting charges/sentencing | 10 | 27 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| Supervised probation | 44 | 38 | 53 | 51 | 48 |

Note: Data represent seven of the eight programs continuously involved in the performance contracting (see text).

On average, the 9655 admissions during the 2002–2006 period, were largely male (78%), employed for pay (54%) and for the most part Caucasian (56%) or African-American (40%). The average age of patients was 33.4 (S.D. = 10.4); 17% reported serious mental illness at admission, and 67% reported a prior history of drug and alcohol treatment. In terms of major drug problems reported, 35% endorsed alcohol, 32% endorsed marijuana, and 21% endorsed cocaine as their primary substance of abuse. Twenty-two percent reported no current legal involvement leading to their treatment episode, while 14% faced pending charges or sentencing, and 47% had been sentenced to probation and supervision.

Importantly, the majority of Table 3 data indicate general stability in patient characteristics, though some yearly trends are worth noting. The percentage of patients endorsing a history of mental illness at admission actually increased over time from 12% of patients to 23%, the number of women attending treatment rose from 20% to 25%, and the number of patients working for pay dropped from 57% to 52%. These trends suggest programs were admitting somewhat more severe patients over time—perhaps because the requirement to maintain 90% capacity pressed them to accept patients they might not have.

Given the finding of greater amounts of program participation with each year of the contract, we were concerned that this could be due to the effect of enforced participation among patients mandated to treatment by the criminal justice system. On the contrary, there was a cross-years increase in the proportion of patients without legal pressure—from 18% to 28%. Finally, it is of interest that only 14.8% of patients (N= 1165) had a second episode of care; and only 3.4% (N= 268) had three or more episodes of care at any time during this five-year period. These low rates of readmission indicate that the contracting mechanism was not simply attracting the same patients multiple times.

4.2.3. Active participation

DSAMH did not simply want admitted patients to “stay longer” which would have been a very easy criterion to report—time between admission and discharge dates. However, such a criterion would have invited falsification; and is not by itself, consonant with good clinical performance. The result is that the participation contingencies were not structured to reward longer lengths of stay—but rather, full participation within each of the treatment phases (see Table 2). Thus, for each month, that capacity utilization targets had been met, DSAMH calculated the proportion of patients in each of the four treatment phases who also met the attendance requirements. For example, all patients admitted within the prior 30 days were expected to have at least eight records indicating attendance.

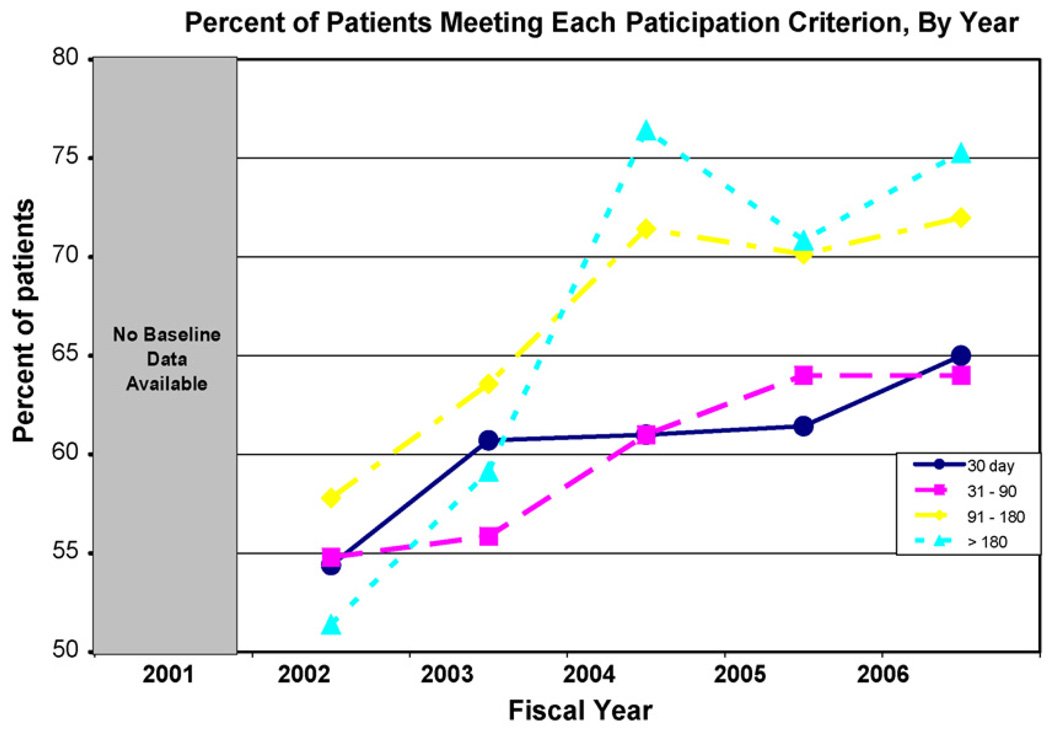

Fig. 2 presents the average proportion of patients who met the active participation performance thresholds in each of the four treatment phases. Note that there is no pre-contract baseline information as data collection for these measures began with the contract in fiscal 2002. The data show a systematic increase in the proportion of patients’ meeting active participation criteria in all four stages of care. The increases were particularly substantial among those in the last two phases (91–180; >180). Though not shown, we also examined these same data for each of the individual providers. As might be expected, there were significant differences among providers in the active participation rates within each of the four treatment phases (these data are available upon request from the senior author).

Fig. 2.

Percent of patients’ meeting each paticipation criterion, by year.

Two points are relevant to a full interpretation of Fig. 2. First, these data do not necessarily mean that more patients were staying in treatment for longer periods over the years. We do know that more patients stayed and participated fully in their first 30 days of treatment. This inference is possible because both more patients were admitted each year (Fig. 1) and because greater proportions of patients were meeting participation criteria in the 30-day phase of treatment (Fig. 2). However, for the rest of the treatment phases performance incentives were calculated separately and there was undoubtedly drop-out between phases. To illustrate, if 10 patients were admitted to a program and all attended eight sessions that month, this would count as 100% Phase 1 participation. If only five patients remained after the first month – but all five attended weekly sessions – that would equal 100% Phase 2 participation. Unfortunately, the only data available to us were the payment threshold calculations (shown in the figure) and not the actual number of patients in each phase of care, that would provide more information.

A second point pertains to the differences in responsiveness to the contingencies among the four treatment phases. As can be seen, the two long-term treatment phases (91–180 days and >180 days) showed substantially more change than the two short-term treatment phases (30 days and 31–90 days). This may be due to a differential level of effort required to obtain the reward bonus across the different treatment phases. The 2002 levels of patient participation were very similar (51–54%) for all phases of care—but the reward thresholds were purposely set at different levels. By the end of fiscal 2002, the average participation rate among 30-day (Phase 1) patients was already at the threshold reward level (50%) and no additional improvement was needed to maintain the bonus. The same was true for the Phase 2 patients (60% threshold) by 2003; and this group also showed little additional improvement beyond that point. In contrast the other two groups had to achieve 70% (Phase 3) and 80% (Phase 4) participation rates in order to receive the reward bonus: this required significantly greater movement from baseline and thresholds were not achieved until 2004.

The relative importance of the contingencies bears re-emphasize. The ability to achieve 80% capacity utilization was critical for the majority (94%) of the funding available to a program and thus their very survival. It is perhaps not surprising that the programs showed remarkable and rapid levels of improvement on that criterion. In contrast, each of the participation criteria could only account for an additional 1% increment; and while seemingly potent enough to engender change (Fig. 2), those rates of change were not dramatic.

5. Discussion

We have described the rationale, procedures and basic evaluation information regarding a novel performance contracting experiment conducted by the Delaware Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health (DSAMH) in their outpatient addiction treatment programs. DSAMH, like all other SSA’s, had been challenged to bring accountability and better clinical management to their statewide treatment systems [24,25]. What makes the Delaware situation particularly interesting is that in an era where so much effort has been expended toward greater specification of the exact clinical procedures that should be used to achieve this goal – e.g. “evidence-based procedures,” “clinical-best practices,” “critical pathways,” etc. [26], DSAMH chose not to focus upon program practices – but rather their clinical performance. DSAMH thus set achievable, measurable target indicators for what “accountable clinical management” would look like; and then used standard contracting methods to reward programs that met those targets. Those administrative and clinical practices that were most consistently associated with the achievement of targeted clinical performance measures were adopted by the system—what Miller has called “practice-based evidence” [14].

In a purely descriptive sense, there are many indications that the performance contracting has been effective. From the perspective of a potential patient, the system now has more treatment venues, better proximity to the most needy populations, more convenient hours of operation and refurbished facilities. Interviews with program administrators and clinical staff at all levels indicate a sense of fairness, clinical value and pride in the achievements so far. From a policy perspective, performance contracting has also recently been applied to the longstanding problem of increasing continuity of care between detoxification and rehabilitative care: new contracts provide significant incentives for patients who transfer from detoxification into stable participation in outpatient rehabilitation treatment.

5.1. Limitations

Despite indications that the performance contracting “works” there are significant limitations to the evaluation design and data [27]. One problem is the lack of a control or comparison group. We did have capacity utilization measures for one year prior to performance contracting; and for both capacity utilization and all active participation measures we have measures from the first “hold harmless” period in 2002. Against those baselines there were clear and orderly increases in all the target measures with the initiation of the performance contracting. However, without data from a similar set of programs that did not have performance contracts, it remains possible that some other general, system-wide emphasis upon quality improvement was fully or partly responsible for much of the observed improvements. In this regard, we have asked the DSAMH representatives about such general quality improvement initiatives and indeed there were several over the course of the five year period. For these reasons, and despite its attractiveness, it is simply not possible to attribute the system improvements exclusively to the performance contracting.

A second limitation is the fact that only payment data from the DSAMH contracting office were available from which to calculate changes in the target performance indicators—but not raw data on fundamental issues such as the number of patients in each phase of treatment; or even dates of first and last appointments. These data leave many important questions unanswered.

Finally, even if it is accepted that the performance contracting was responsible for the observed gains in utilization and patient participation, these criteria are related to, but not an adequate proxy for, traditional rehabilitation outcomes capturing the broader goals of recovery embraced by most providers [28,29]. Thus, while these criteria have many strengths, particularly in clinical and administrative management, it remains to be seen whether and to what extent they relate to traditional outcomes.

5.2. Implications

Given the significant limits on causal inference from the available evaluation information, what are the reasonable implications from this interesting, real-world experiment? We think three merit discussion.

First, all indications that are relative to other system-wide efforts to improve treatment accountability, performance-based contracting is less costly and complicated to implement and seemingly quite compatible with other accountability initiatives. Put simply, it is the type of intervention a small to mid-sized system could do within the limits imposed by most contemporary budgets. As also seen in performance contracting experiments in the general healthcare literature, there are right and wrong ways to implement these contracts. The DSAMH principles (described below) offer some important benchmarks for other agencies interested in this type of contracting.

As implemented by DSAMH, the performance-based contracting did not require significant training in new clinical or administrative techniques, nor the hiring of different personnel. Though an efficient, responsive information system was essential to the operation of the contracting and reimbursement procedures, that system was not complicated to administer. Also, the performance contracting did not interfere with – and in fact fostered interest in – system adoption of new, evidence-based clinical interventions such as Motivational Interviewing [18] and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [19]. The explicit setting of financial incentives based upon achieving patient engagement and retention goals, essentially set the necessary conditions under which there was both clinical and financial benefit to programs to institute these therapies.

A third implication from this application of performance contracting is that it had intuitive appeal to all parties associated with the process. Patients, program administrators, clinicians and policy makers immediately understand the essence of the intervention. Providers proudly talked about how the performance contracts could work for them clinically and financially. The strategy as implemented simply makes economic, managerial and clinical sense.

5.3. What lessons can be learned from the Delaware Model?

There were three important general principles underlying the original design of the performance-based contracting system that we think led to the positive results seen. First and most importantly was that patient behaviors, rather than provider processes were the foundation of the performance system. This principle was quite consistent with DSAMH’s responsibility not only to meet the needs of the individual patient but also to improve public health through better management of patients.

The decision to measure patient performance during the course of outpatient treatment rather than 6–12 months following treatment discharge was critical for establishing clinically and financially manageable contingencies within the contract mechanism. Providers have legitimately complained that patient outcomes, measured months after discharge, are not within their clinical ability to control or to accept responsibility for. Here programs were asked to take clinical (and now financial) responsibility for engaging and retaining patients in the treatment process—a very realistic scope of work for the programs. Finally, the during-treatment measures of patient engagement and participation were administratively feasible to collect and report through the information system; and were subject to audit for accuracy.

A second important principle that DSAMH decided upon early within the general design of the system was that the process by which financial incentives were set should foster collaboration among providers. The performance contracting system could have been designed to provide extra financial rewards for the “best” programs within the network, inevitably pitting one program against another. Instead, the performance criteria for each program were based upon their individual capacity and provider-wide agreement on levels of appropriate patient participation.

This design feature encouraged each provider to try any legitimate set of administrative and clinical procedures they thought might enhance performance; and to share those “best practices” with the other programs, without detracting from their own potential earnings. From a clinical perspective a collaborative system was clearly necessary for adequate treatment of patients who sometimes moved from one region to another and who would be expected to transition across different levels of care that were not available from all providers. A competitive system that adversely affected patient transition would have detracted from the focus of improving client services. From a methodological perspective, an inter-program system of competition would have had to consider between-program differences in patient characteristics in the evaluation; so-called “case mix adjustment.” Most researchers would agree that all forms of statistical efforts to adjust for case mix differences are flawed and subject to challenge [30].

A final general design principle for the system was that the performance incentive dollars would be calculated and reimbursed to the programs each month, rather than in a lump sum at the end of a year. This may appear to be a mundane property of the system but in fact, close contiguity between behavior and incentives (rewards) is a critical behavioral principle [1–3]. Beyond the psychological aspects, most of the programs essentially went at risk for new funding, and rapid return of the earned income (within 30–45 days of invoice receipt) was necessary to maintain liquidity and assure adequate cash flow.

6. Conclusion

Despite the obvious limitations in the evaluation information, we think this novel, state-wide experiment in performance-based contracting suggests some important lessons for researchers, providers and policy makers. First, as implemented, the performance contracting mechanism may have actually set the financial conditions necessary for fostering clinical innovation and improvement. Second, as implemented, the performance contacting was administratively, clinically and politically feasible to apply. Third, as implemented, the performance-based contracting offered these real world programs the unusual opportunity to determine for themselves whether their own, or some research-derived interventions would produce evidence of better clinical and financial performance. While it is fair to say that interventions that produce better performance during treatment may not produce better post-treatment outcomes—the reverse is also true.

Finally, the reader will note that we have repeated the phrase “as implemented” in all our conclusions. This is to emphasize that while the contract mechanism between a state or county government agency and community providers can be a major instrument of clinical policy and practice, there is need for real care in the selection of contract contingencies, criteria and incentives for it to achieve its potential. In future work we hope to more fully investigate the interactions between this type of provider-level contract and clinician-level clinical interventions toward the goals of improved care and better management.

Footnotes

Work on this project was supported by NIDA Grants RO1 DA13134 and R01 DA015125; and by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the work, nor in the writing or submission of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Higgins ST, Silverman K, editors. Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers: contemporary research on contingency-management interventions. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamb RJ, Kirby KC, Morral AR, Galbicka G, Iguchi MY. Improving contingency management programs for addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:507–523. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Raczynski JM, Caldwell E, Engle M, Michael M, et al. Sufficient conditions for effective treatment of substance abusing homeless persons. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1996 December;43(1–2):39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidorf M, Hollander JR, King VL, Brooner RK. Increasing employment of opioid dependent outpatients: an intensive behavioral intervention. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1998 March;50(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Farrell TJ, Choquette KA, Cutter HSG. Couples relapse prevention sessions after behavioral marital therapy for male alcoholics: outcomes during the three years after starting treatment. Journal Studies on Alcohol. 1997;28:341–356. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhmerker K, Hartman T. Pay-for-performance in state Medicaid programs. The Commonwealth Fund. Report #1018. 2007 Available at http://www.cmwf.org.

- 9.Rosenbaum S. negotiating the new health system: purchasing publicly accountable managed care. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14 Suppl. 3:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kizer K. Establishing health care performance standards in an era of consumerism. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(10):1213–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maio V, Goldfarb N, Carter C, Nash D. Value-based purchasing: a review of the literature. The Commonwealth Fund. Report #636. 2007 Available at http://www.cmwf.org.

- 12.Commons M, McGuire T, Riordan M. Performance contracting for substance abuse treatment. Health Systems Research. 1997;32(5):631–650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Y. Selection incentives in a performance based contracting system. Health Services Research. 2003;38(2):535–552. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller SD, Mee-Lee D, Plum B, Hubble M. Making treatment count: client-directed, outcome informed clinical work with problem drinkers. In: Lebow J, editor. Handbook of clinical family therapy. New York: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1980;168(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The fifth edition of The Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Carise D, Alterman AI. The ASI at 25: a review of findings, problems and possibilities. American Journal on Addictions. 2005;15:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bien T, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88(3):315–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gawin FH. A comparative trial of psychotherapies for ambulatory cocaine abusers: relapse prevention and interpersonal psychotherapy. American Journal on Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1991;17:229–247. doi: 10.3109/00952999109027549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM. Drug abuse treatment: a national study of effectiveness. Chapel Hill (NC): University of North Carolina Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moos RH, Finney JW, Cronkite RC. Alcoholism treatment: context, process and outcome. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crossing the quality chasm: improving the quality of care for mental and substance use disorders. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2006. Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garnick DW, Lee M, Chalk M, Gastfriend D, Horgan CM, McCorry F, et al. Establishing the feasibility of performance measures for alcohol and other drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;45:124–131. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization. Attributes of core performance measures and associated evaluation criteria. 2002 Available at http://www.jcaho.org/pms/core+measures/attributes+of+core+performance+measures.htm.

- 26.Roman PM, Johnson JA. Adoption and implementation of new technologies in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salasin SE, Davis HR. Facilitating the utilization of evaluation: a rocky road. In: Davidoff I, Guttentag M, Offutt J, editors. Evaluating community mental health services: principles and practice. Rockville (MD): National Institute of Mental Health, The Staff College; 1977. pp. 428–443. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLellan AT, McKay JR, Forman R, Cacciola J, Kemp J. Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: from retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction. 2005;100:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCaffrey D, Ridgeway G, Morral A. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating adolescent substance abuse. Psychological Methods. 2004;22:34–42. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]