Abstract

In a 3-year longitudinal, mixed-method study, 67 children in two schools were observed during literacy activities in Grades 1–3. Children and their teachers were interviewed each year about the children’s motivation to read and write. Taking a grounded theory approach, content analysis of the child interview protocols identified the motivations that were salient to children at each grade level in each domain, looking for patterns by grade and school. Analysis of field notes, teacher interviews, and child interviews suggests that children’s motivation for literacy is best understood in terms of development in specific contexts. Development in literacy skill and teachers’ methods of instruction and raising motivation provided affordances and constraints for literate activity and its accompanying motivations. In particular, there was support for both the developmental hypotheses of Renninger and her colleagues (Hidi & Renninger, 2006) and of Pressick-Kilborne and Walker (2002). The positions of poor readers and the strategies they used were negotiated and developed in response to the social meanings of reading, writing, and relative literacy skill co-constructed by students and teachers in each classroom. The relationship of these findings to theories of motivation is discussed.

Teachers of young children often list “developing a love of reading and writing” as among their most important literacy goals for their students (Nolen, 2001). Yet relatively little research has focused on the process of developing literacy motivation among the youngest readers and writers. In part, this lack is due to the difficulties of applying traditional approaches of motivation research to young children. Previous research on motivation to read, for example, has relied on self-reports, particularly surveys (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Guthrie, Van Meter, McCann, & Wigfield, 1996). Concern about how young students interpret survey and interview questions has limited their use. Some researchers have relied on teacher or parent questionnaires (e.g. Baker & Scher, 2002) but these strategies make it difficult to discern the child’s perspective. Even less research has taken the literacy learning context into account. The study presented here uses ethnographic observation, along with interviews of students and their teachers, in a longitudinal design to examine changes in literacy motivation over three years for primary students in two schools.

Motivation theory has seen a recent shift from considering context as an independent variable influencing individuals’ motivation, and toward considering motivation itself as socially constructed, both influenced by and influencing the meaning of acts and beliefs in contexts. Such a position entails the possibility that individuals’ definitions of motivation, interest, learning, achievement, and other constructs are different in different situations, and that they develop over time. Some motivation theories distinguish between stable, trait-like orientations and situation-specific involvement (Nicholls, 1989; Nolen, 1988; Thorkildsen & Nicholls, 1998). Hidi and her colleagues (Hidi, 1990; Hidi & Anderson, 1992; Hidi & Berndorff, 1998; Renninger & Hidi, 2002) distinguish between situational interest, a temporary state of being drawn to an object, and individual interest, a stable or trait-like attraction to the same object over time.1 It has been suggested, with some empirical support, that situational interest, if sustained over time by providing interesting and autonomy-supportive instructional environments, can develop into a stable individual interest (Hidi, Berndorff, & Ainley, 2002; Krapp, 2002; Lipstein & Renninger, 2006; Mitchell, 1993; Renninger & Hidi, 2002). Reading, for example, could lead to the development of individual interest in specific topics (Hidi et al., 2002), but may also lead to or be reinforced by a well-developed interest in the activity of reading (Renninger & Hidi, 2002).

Most motivation research has been deductive, proceeding from a particular theory (with its particular definitions of motivation, achievement, interest, and the like) to hypothesis testing and back to theory. Developmental studies have been primarily cross-sectional or of relatively short duration, making assumptions about the meaning of motivational constructs across time that may not be warranted (Nolen, 2004). For studying motivation development as situated in social contexts, however, taking the students’ perspectives into account, other approaches become necessary. In particular, some way to account for the role of social contexts and the changing meanings attached to various motivated actions is needed (Pressick-Kilborn & Walker, 2002; Walker, Pressick-Kilborn, Arnold, & Sainsbury, 2004).

Recently, a number of researchers have taken a more ethnographic approach to studying the role of context in motivation for learning over time (e.g., Nolen, 2001; Oldfather, 2002; Oldfather, West, White, & Wilmarth, 1999; Pressick-Kilborn & Walker, 2002; Renninger & Hidi, 2002; Thorkildsen, 2002; Thorkildsen, Nicholls, Bates, Brankis, & DeBolt, 2002; Walker et al., 2004). In the longitudinal study presented here, the analysis characterized children’s emic views of reading and writing in particular contexts, including the reasons for reading and writing they found salient. The role of the classroom contexts in children’s adoption of these reasons was explored through analysis of ethnographic fieldnotes, and teacher and child interviews. Change over time was analyzed in relation to increasing levels of literacy skill and to changes in classroom context as children moved from one grade to another.

MOTIVATION TO READ AND WRITE

Reading and writing are particularly rich areas for motivation research because there are so many reasons for engaging in these activities, and because of the essentially social nature of literacy. Reading can be a source of pleasure, a source of information, a classroom task, or a context for social interaction. It can be seen as a means to gaining knowledge or status, or as an enjoyable activity in itself. One of the few studies of reasons for reading taking an emic perspective is the work of Guthrie and his colleagues (Guthrie et al., 1996). They used a semi-structured interview to identify 13 different reasons for reading2 in a sample of 20 third- and fifth-grade students participating in the Cognitively Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) reading intervention. The CORI intervention stresses reading to understand and learn about interesting topics in science, and presents specific strategies in the context of purposeful reading. Children gave reasons for reading ranging from interest in learning more about a science topic, to compliance with authority, to reading to avoid work. The reasons for reading that are salient to children may be, in part, a result of the reasons stressed in their schools or classrooms. Because Guthrie and colleagues interviewed only the CORI intervention group, this possibility could not be addressed.

Like reading, writing also has utilitarian, tool-like aspects but can be seen as means of social interaction or an inherently engaging activity in its own right. Silva and Nicholls (1993) found that adult college students’ beliefs about what it meant to write well and their goals for writing were related to their intrinsic motivation to write. They identified three definitions of success in writing with distinctive goals: creativity and self-expression goals, goals of improving logical reasoning and knowledge of subject matter, and the goal of being methodical and correct in surface-level conventions (e.g., punctuation and spelling). Creative self-expression goals were most strongly related to intrinsic commitment to writing. Children’s goals and motivations are likely to be related as well, but may change with instructional and social context. In classrooms where student writing is shared with a wide audience, for example, the goal of creative self-expression or entertaining one’s friends might rise to the fore.

The Role of Social Context in Developing Literacy Motivation

The social contexts in which reading and writing occur contribute to children’s notions of the nature of reading and writing and their place in school and family life (Baker, Scher, & Mackler, 1997; Freppon, 1991; Heath, 1982; Scher & Baker, 1997). Numerous researchers have documented relationships between instruction and other contextual variables and motivation for literacy (Bogner, Raphael, & Pressley, 2002; Guthrie & Alao, 1997; Guthrie & Knowles, 2001; Oldfather, 2002; Oldfather & Dahl, 1994; Thorkildsen, 2002). In a series of studies, Guthrie and his colleagues, for example, found that motivation for expository reading is greater when instruction is organized around a conceptual theme; students interact with tangible objects, events, or experiences; students are allowed opportunities for self-direction, self-expression, and social collaboration; and students are provided with interesting texts and supports for strategic reading, including modeling and coaching, peer discussions, and student reflection (Guthrie & Knowles, 2001).

Instruction that provides cognitive and emotional supports for learning can also increase students’ motivation (Turner et al., 1998). Allowing students to pursue their interests, for example, does more than provide a sense of autonomy and self-direction. It allows children to make use of prior knowledge useful for understanding and producing text (Hidi & Anderson, 1992; Hidi et al., 2002), making success experiences more likely and fostering self-efficacy and positive emotions (Pajares, 2003; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002; Walker, 2003). Teachers who normalize individual differences by using methods that allow for individual differences in skill, purpose, and strategy can communicate to students that they are valued for who they are, encouraging students to be honest about their weaknesses and to take pride in their strengths (Oldfather, 2002; Thorkildsen, 2002; Thorkildsen et al., 2002).

The place of literacy (and of reading and writing competence) in the social structure of the classroom may also influence children’s motivation to learn. Literacy is highly valued in most societies (and classrooms); thus, mastery or competence motivation (Nicholls, 1989; White, 1959) might be important to young children. Children may also begin to internalize adults’ reasons for reading and writing as necessary for success in life or social relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Thorkildsen, 2002). Becoming a skilled reader and writer might confer social status if teachers prefer those with higher literacy skills (West, 2002). At the same time, such status differences might provide added incentive for less-skilled students to increase their efforts. Although it has been primarily treated as an individual difference variable, interest can also be fostered and channeled by peers, teachers, and other aspects of the social context (Pressick-Kilborn & Walker, 2002; Walker et al., 2004).

The Role of Interest in Motivation for Literacy

Interest is usually studied as an individual difference variable, and refers to the affective and cognitive interaction of a person with an interest object (e.g., topic, activity, physical object) (Hidi, 1990; Krapp, Hidi, & Renninger, 1992). To date, studies of interest in reading and writing have primarily focused on the influence of interest on learning from text (Hidi & Anderson, 1992; Schiefele, 1990, 2001) or quality of writing production (Benton, Corkill, Sharp, Downey, & Khramtsova, 1995; Hidi et al., 2002; Hidi & McLaren, 1991). The type of interest generally invoked is “topic interest,” or interest in a subject-matter area. If one were interested in the subject of human development, for example, one would be expected to process texts on human development more deeply and effectively, and to produce longer and more elaborated text on the topic. Reading and writing activities are viewed as means to an end—tools to be used in learning and communicating about interesting topics. Nevertheless, it is possible to consider interest in reading and writing for their own sake as interesting activities. This possibility has received less research attention.

Reading and writing share certain characteristics relevant to interest and motivation. Both can involve working with more or less interesting texts. Both reading and writing can be used for utilitarian purposes; both can afford pleasure and present challenges to the learner. Motivation to read and motivation to write also differ from each other in some fundamental ways. Interest in reading may consist primarily of an opportunity for what Schiefele (2001) calls “object-related” interest, stimulated by the material that is read rather than the act of reading itself. Writing is different in that is primarily an act of creating or producing texts, rather than consuming them. In situations where the writer has some choice in the manner or subject of composition, the motivation for text production may come, in part, from an interest in the topic, but may also emerge from the positive emotions that accompany creativity and self-determination (Pekrun et al., 2002). Because interest has a clear relationship to ongoing intrinsic motivation and to learning from and producing text, the development of interest is explored in this study.

A LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF LITERACY MOTIVATION DEVELOPMENT

This study uses a longitudinal design to examine changes in individuals’ motivations to read and write across 2 or 3 years. It builds on previous research in a number of ways. It extends research on the role of classroom context on motivation by following children across different literacy contexts over 3 years. This longitudinal design provides data on changes in both literacy skill and the role of literacy in the classroom. It provides an opportunity to assess the motivations that are salient from the child’s perspective, and to compare these motivations with the constructs in current motivation theories. The study also provides an opportunity to look for evidence regarding the developmental prediction that situational interest over time might lead to more stable individual interests (Renninger & Hidi, 2002).

Unlike much research on the development of motivation, it should be noted that this is not a study of how levels of motivation change over time, but is a study of how the salience of different motives changes with development and experience in contexts. I take an ecological perspective on development, assuming that it is unrealistic to try to separate the effects of literacy development from the contexts in which they occur. This does not mean that there are not more generalized developmental trends accounting for similar patterns in different contexts. In a small-scale longitudinal study such as this one, it is possible to get to know the individuals and their classroom contexts in enough detail to examine how changes in both may be related to differences in children’s reasons for reading and writing (see also Pressick-Kilborn & Walker, 2002; Walker et al., 2004).

A NOTE ON METHODOLOGY: USING MULTIPLE METHODS

Pekrun and his colleagues (Pekrun et al., 2002) called for the use of qualitative research as a way to check the conceptual breadth of existing theories of motivation. An exclusive use of experimental or survey research, they argue, can result in missing aspects of interest and motivation that are important to students. Neglecting the complexity of the social contexts in which interests and motivation develop can similarly result in missed opportunities to understand the processes involved. In this longitudinal study, multiple methods were used, including content and prevalence analyses of children’s interview protocols, ethnographic observations of literacy activities in classrooms, and teacher reports of goals, practices, and observations of their students’ change over time. This approach made it possible to study the aspects of reading that children saw as salient motivations to read and write, how various aspects of motivation and interest were related, how the reasons for literacy changed as children became more experienced and able readers and writers, and how the trajectories of specific aspects of interest and motivation arose in different classroom contexts. The use of multiple methods allowed for triangulation of data and interpretation.

Grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was considered the most appropriate approach to this study, given the relative rarity of motivation research at these age levels and the methodological and measurement issues involved. Deductive research searching for changes in the amount of motivation over time faces challenges due to a lack of construct invariance across developmental levels and contexts. For example, “mastery” of writing may mean “better spelling” to a beginning writer or to one in a classroom where conventions are stressed over meaning. Mastery may be construed as “better communication of my ideas” to an older, more skilled writer if that function of writing is stressed in school (Graves, 1983). Differences in item interpretation complicate the interpretation of changes in responses to fixed motivation scales. However, it is not a problem for grounded theory, which assumes that meanings differ systematically across individuals and contexts. Analysis begins with the words and actions of the participants, and the aim is to construct concepts and categories that reflect participants’ own meanings. This is not to say that existing theories and constructs do not influence the analysis. Strauss and Corbin caution that researchers should use concepts from the literature “with care, always making certain that they are embodied in these data and then being precise about their meanings (similarities, differences, and extensions) in the present research” (p. 115). This is particularly relevant to the current research, where one of the questions regarded whether current theoretical constructs in motivation and interest were reflected in students’ own concerns.

Research Questions

In a grounded theory approach, researchers may begin with initial research questions to focus observations, but leave themselves open to modifying or adding to the research questions in response to ongoing analysis of the data, using constant comparison of data to emerging categories and their properties. The initial research questions for this study were:

What motivations for literacy are salient to children across the primary grades (in which they are becoming fluent at reading and producing text)? How do these motivations compare to the constructs in current theories of motivation and interest?

-

Which motivations remain salient and which change over time? Can changes be described as development-in-context?

What is the evidence that changes are related to development of reading and writing skill?

What is the evidence that these changes occur in relation to classroom social context, particularly the social construction of conceptions of reading and writing? What aspects of the social context seem most related to the salience of different motives?

-

Is there evidence to support a proposed development of individual interest from sustained situational interest in reading and writing?

In the second year, a fourth research question arose in response to classroom observations that suggested the emergence of ego concerns. In Grades 2 and 3, ego concerns can emerge as children begin to become aware of how differences in ability can limit the effects of effort on performance (Nicholls, 1989; Nicholls & Miller, 1984). Increasing ego involvement can lead students to withdraw from activities to avoid looking incompetent. This concern can be increased in environments that stress social comparisons and privilege those with superior ability (Nicholls, 1989). Together with one of the teachers (Ms. Bowers), I noticed that some struggling Grade 2 readers seemed to be withdrawing from reading activity. To explore students’ views of ability differences, the following research question was added:

How are individual differences in reading viewed and treated by students in different contexts, and at different ages? How might this affect motivation, particularly in struggling readers?3

This study is part of a research program investigating the development of motivation for literacy in children aged 5–10 years. For 4 years, beginning with kindergarten (Nolen, 2001), children and their teachers were observed regularly in their classrooms and interviewed annually about reading and writing. The study reported here focuses on the data from Grades 1–3.

Method

Participants

Across the three years of the study presented here, a total of 67 students, beginning in Grade 1 (n = 49, average age 6–7 years) and ending in Grade 3 (n = 36, average age 8–9 years), and their teachers, recruited from two suburban elementary schools in the northwest United States, participated.4 School 1 served a high socio–economic status (SES) population, with an average across the three years of 2% receiving free or reduced lunch; School 2 served a low-to-middle income population, with an average of 40% free or reduced lunch. Although both schools averaged 78%, White—the ethnic composition was somewhat more diverse in School 2, with 4% Black, 8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 3% Native American, and 6% Latino. The second largest ethnic group in School 1 was Asian/Pacific Islander (18%) with less than 2% in any other group. The total sample included all students who had participated in any grade, and was used to develop the coding scheme. All teachers in the study were White. All teachers were veterans with over 15 years experience, except for Ms. Donovan, who was a beginning-level teacher.

The longitudinal subsample (n = 36), which provided the data for the developmental analyses, comprised students who were interviewed annually for either 2 (n= 23) or 3 (n=13) years of the study. In School 1, children who had been together in K-1 were shuffled and classes recomposed. Because of access issues, this resulted in 1 loss and 13 new students in School 1 Grade 2. This group stayed stable in Grade 3. The School 2 (multi–age) class stayed stable across 3 years (adding 2 students in Grade 2, the other differences in sample were due to equipment issues). The subsample included 29 European Americans, 2 Asian Americans, 1 African American, 1 Latino, and 2 unknown. There were 9 boys and 12 girls from School 1, and 8 boys and 6 girls from School 2. One student had received but was no longer receiving English as a Second Language (ESL) services at the time of participation in this study.

Procedures

Recruitment of teachers

At the beginning of this study, Grade 1 teachers from two schools were recruited from a group participating in a summer literacy workshop, part of a larger study of literacy instruction (see McCutchen et al., 2002; McCutchen & Berninger, 1999). Ms. Adams (School 1, higher SES) and Ms. Norman (School 2, lower SES) were both experienced and highly regarded in their schools.5 In School 1, 2 Grade 2 teachers (Ms. Bower and Ms. Curtis) were recruited from among those who received students from Ms. Adams’ class. Students in these classes remained together during Grade 3, with Ms. Bower’s students moving to Ms. Donovan’s class, and Ms. Curtis’s students moving to Ms. Evans’s class. In School 2, Ms. Norman team-taught a multiage (Grades 1–3) class with Ms. Oliver. Adams, Bowers, Norman, and Oliver attended the workshop and agreed to participate in the study. The teachers are described in Appendix A, with a focus on their goals and instructional techniques.

Classroom observations

Each class was observed seven or eight times from fall to spring each year by the author.6 Observations lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours. During the observation, detailed fieldnotes were taken using a laptop. The focus was on any literacy-related activity (any activity related to reading or writing, no matter the subject area). The study presented here was part of a larger project focused on the development of motivation in struggling readers and writers in social contexts. Thus, three to four “target” students who were struggling with reading and/or writing, or who had struggled in the past, formed the nucleus of the field observations.7 During the course of these observations the children took part in large- and small-group activities and lessons (small groups were flexible and changed frequently) and received individual attention from teachers and other adults while I attempted to capture verbatim the teacher’s and students’ talk. Over the course of the year, these students interacted with all or most of their classmates, and peer-to-peer conversations were also observed and recorded “live” via fieldnotes. In addition to providing specific information about the target students, the observations were analyzed as part of the present study of the larger sample.

Child interviews

Interviews were conducted during the last 2 months of each school year in a quiet location outside the classroom, primarily by the author but with six children in the third year interviewed by a research assistant. All participating children were individually interviewed about reading and writing; each interview took between 20 and 25 min to complete. In Grade 1, the interviewer used a monkey hand-puppet which “asked” children to describe reading and writing in school. In Grades 2 and 3, the interviewer explained that she was interested in how children’s views might have changed from the previous year. In all three grades, the first questions were purposefully very general, to see whether children raised motivational issues spontaneously when discussing their reading and writing. The interview ended with a more specific question to elicit their views on the necessity of learning to read and write and their views about reading and/or writing in groups. The entire interview was analyzed for content related to motivation, but the questions (and probes) which prompted this content were:

Tell me about reading (writing) this year in school. (Follow-ups to affective responses were: What do you/don’t you like? What’s fun about it?)

What kinds of things do you read (write) in school?

-

Do you read (write) at home or outside of school? What kinds of things?

If the child mentioned preferences in answer to these questions, the interviewer probed for more details. For example, “What do you like about Harry Potter?”

Are there any things in particular you like to read (write) or read (write) about?

Do you think everyone should learn to read (write)? Why/why not?

Do you ever read (write) with other people? How is that?

Reading scenarios

To address the fourth research question about children’s views of ability differences, two sets of interview questions were added in second year. First, children were shown line drawings of children reading alone, in pairs, or in groups of four. They were asked which way of reading they preferred, and why. This question was included to surface any personal worries about reading in public, as well as any social reasons for reading. Second, a hypothetical situation highlighting ability differences was created to tap children’s perspectives on the social status, treatment, and motivation of poor readers. To avoid priming them to focus on any particular construal of ability or on ability per se, it was important that the interviewer not label students as “better” of “poorer” readers. Instead, the interviewer modeled the reading of each child aloud as the children participated in an imaginary round-robin reading group.

Using the line drawing of four children reading together, the interviewer demonstrated the reading of two imaginary fluent and one disfluent reader, indicating the drawing of the “reader” each time. The disfluent reader was always the same sex and apparent ethnicity as the interviewee. At the point where the interviewer demonstrated getting stuck on the word “knelt” (“k-k-k-n-e…”), the child was asked:

What should the other kids do? (This elicits knowledge of helping strategies.)

Why would that be a good thing to do? (This surfaces conceptions of reading in social situations, possible outcomes of helping strategy use.)

How would (he/she) feel if the other kids did that? Why? (This elicits awareness of emotional implications and beliefs about how poor readers should be treated by those who are more able.)

What if every time he/she got stuck on a word like that, the other kids gave him/her the word? Why? (This elicits consequences of over-helping or appropriateness of helping strategies.)

We don’t know what they would really do, but how do you think these kids would feel about having this boy/girl in their group? Why? (This elicits knowledge of social implications, status differences, as well as beliefs about the purposes of reading in groups).

Finally, to mitigate any negative feelings aroused by these questions, children were asked to name their favorite recess activity, and engaged briefly in conversation about it. Children were thanked for their help and escorted back to their classrooms.

Teacher interviews

After the end of the school year, teachers were interviewed by the author at a location away from the school. Because Ms. Norman and Ms. Oliver team-taught a multiage class, divided so that second graders were split between them, these teachers were interviewed together after the Grade 2 year of the study. Teachers were asked to describe their goals, instructional techniques, and the progress of target children. All interviews were taped and transcribed verbatim. Teacher interview questions are listed in Appendix B.

Analysis and Results

Analysis Overview

Consistent with a grounded theory approach, the first step in analysis was to identify and categorize the ways children talked about motivation to read and write during the interviews. Content codes were developed as described below, and the qualitative changes in motivational talk over the 3 years of the study were characterized. Next, the salience or prevalence of the major categories of motivational talk was estimated through quantitative analysis, along with changes in salience with age. The patterns revealed by this quantitative analysis were then explored through additional qualitative analysis of student interviews, field notes, and teacher interviews. Field notes and teacher interview data were used primarily to help in analyzing the patterns observed in the content analysis by providing a context and crosscheck for students’ remarks. A more detailed analysis of 2 third-grade teachers’ interview data and field notes was aimed at exploring between-class differences in changes from Grade 2 to Grade 3. All interview transcripts and field notes were analyzed using ATLAS/ti qualitative analysis software (Version 4.2, Build 61, Scientific Software, 1996–2003).

Content Analysis of Interviews: Coding Children’s Motivational Talk

Code development

In keeping with a grounded theory approach, code development proceeded from the bottom up; that is, codes were created to capture the ways children talked about their feelings about reading in school and at home. To develop the coding scheme, the author, a researcher familiar with a variety of motivation theories, read transcribed interviews from Grade 1 for content related to motivation to read or to learn to read. These codes were then grouped by similar content into minor categories. The minor categories were inspected for their relationship to theoretical constructs from research on motivation and interest, and major theoretical categories were created that subsumed the minor categories. Multiple readings of quotations in the context of the entire interview, as well as comparisons to field notes collected during the year and teacher interviews, led to refinement of codes and categories.

This process was repeated for Grade 2, beginning with the codes developed for Grade 1, but with new codes and minor categories added to capture new ideas expressed by second graders. Then Grade 1 interviews were reread in light of the Grade 2 codes and categories, and refinements made. At this point, a subsample of 20% of the combined Grade 1 and Grade 2 interviews was coded by three additional coders unfamiliar with motivation theory to check and refine the reading categories (Nolen & Gonzales, 2000).

The code-development procedure was repeated for Grade 3 interviews. Finally, interviews from all three grades were reread to check for theoretical consistency within and across grades. Next, writing codes for Grades 1–3 were developed using the same procedures. The final step was to have new coders recode a subsample of about one-third of the interviews in each grade. Any inconsistencies in coding were corrected at this point. Interrater agreement was above 90% for each grade and subject area. Final coding decisions were made by the author. Major and minor category codes with sample descriptive codes and examples of student quotations are shown in Appendices C and D. Two descriptive codes with sample quotes from each grade level are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sample Quotes for Two Descriptive Codes

| Reading Interest: Get involved with plot, characters: |

| 1st Grade: [Reading is fun because] if you really like a story, it’s like you’re going into stories when you’re reading it. |

| 2nd Grade: Well, it’s like fun. It’s like adventure… It’s like I was someone in an explorer book, like Harry Potter, like I was part of the characters. |

| 3rd Grade: I like reading about Mary Kate and Ashley; they’re twins, they’re in Hollywood. They’re like 13. |

| Creative Self-Expression: Like having choices, creative control |

| 1st Grade: [Writing is] fun, and sometimes you get to write about whatever you want. |

| 2nd Grade: Like if we get free writing, we get to write about anything you want and then that’s fun. |

| 3rd Grade: Its fun to think about it, if you get to make the decisions, rather than, “OK, you write this, you write that.” Because it’s not your creation, it’s not your idea. It’s better if you got to make your idea. |

Content analysis

Major and minor codes were similar for motivation to read and write. For both subjects, children talked about three aspects of task orientation (Nicholls, 1989): mastery, interest, and enjoyment. A fourth aspect differed for reading and writing: For reading, children talked about making sense of what they read, long considered an aspect of task orientation (Nicholls, 1989). For writing, children talked about creativity, choice, and self-expression, combined in the code “Creative Self-Expression.” Silva and Nicholls (1993) found a similar category in older writers. Children also talked about reading and writing as extrinsically motivated school tasks and as sources of ego concerns; they discussed social motives as well as utilitarian reasons for learning both subjects. Finally, some children talked about both reading and writing avoidance.

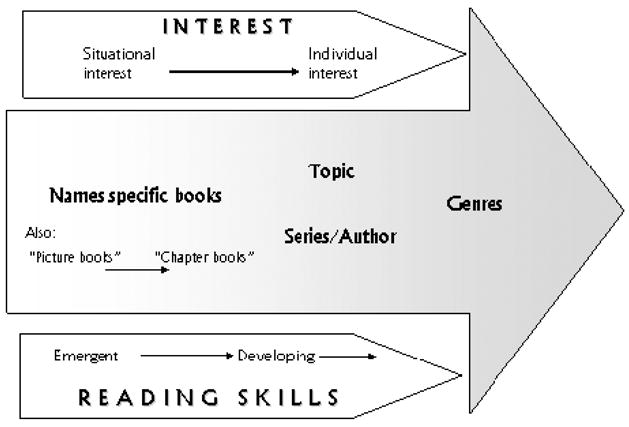

Increasing complexity of talk about interest

In both reading and writing, students developed increasingly differentiated ways of describing their motivation. This differentiation is particularly evident in their talk about interest. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, students’ talk became more detailed with age, requiring additional codes to capture meaning, especially as students moved from talking about situational interest to more stable, individual interests. There were also parallels in the nature of the interest students described for reading and writing: Three of the four types of interest mentioned were the same in both subjects. Students talked about both topic and genre interest in Grade 2, and by Grade 3 were also expressing interest in the activity of reading and writing.

TABLE 2.

Codes for Interest in Reading, by Grade

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest | Like specific book Get involved with plot or characters Likes books, stories |

Like specific book Get involved with plot or characters Likes books, stories Interest is necessary to enjoy reading Why-favorite: funny, exciting Like to read comics, magazines |

Get involved with plot or characters Likes books, stories Interest is necessary to enjoy reading Why-favorite: funny, exciting |

| Topic | Like to read favorite topic | Like to read favorite topic Like certain topics |

|

| Genre | Like to read: Nonfiction Favorite series, author |

Like to read: Nonfiction Favorite series, author Favorite genre |

Like to read: Favorite series, author Favorite genre Why-favorite: writing style |

| Activity | Love to read all the time Reading is interesting Why-favorite: interesting Why learn to read: to read interesting books |

TABLE 3.

Codes for Interest in Writing, by Grade

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writing Stories | Like writing stories and poems Write stories/books at home |

Like writing stories Write stories at home Why learn to write: so can write stories |

Like writing stories Like to write at home: stories, group story with friends, ideas for publishing at school Why learn to write: so can write stories |

| Topic | Like to write on favorite topic Favorite writing: topic |

Like to write on favorite topic Favorite writing: topic Like to write if topic is good |

|

| Genre | Favorite writing: genre Write poetry at home Like rhymes, sound play |

Like to write at home: poetry, jokes, essays, book reports, nonfiction Like to write: favorite genre Favorite writing: genre |

|

| Activity | Like to write because it is interesting This year writing is more interesting Writing makes life interesting |

As expected, the students’ ways of describing their interests reflected their increased knowledge of a range of genres and purposes for reading and writing. This finding likely reflects not only that older children are more articulate in describing their thoughts and feelings, but also that their notions of literacy and their interest in it were also developing. Compare Odelia’s responses while in Grade 1 at School 1 to her responses 2 years later.

Interviewer: Well, tell me about reading. What’s reading like at school?

Odelia (1st grade): Well, it’s fun.

Interviewer: What makes it fun?

Odelia: The stories.

In Grade 1, Odelia described her interest in reading in very general terms. By Grade 3, Odelia talked in more detail about her reading interests, specifying ongoing interest in book series and the works of certain authors:

Odelia (3rd grade): Well, the reading in school this year is very challenging because it’s harder than last year but I like the books that we’re reading, like I read “Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes,” it’s sad but it’s an easy story to read. [At home] I like to read like “Ramona,” those books? I read that to my friend. And she started laughing… And I like to read the Roald Dahl books. And I just read a lot of other books.

Similar growth is shown in Aidan’s responses to questions about writing. While in Grade 1 at School 2, he shows an interest in writing stories and poems, but speaks in very general terms (“I just like it”).

Aidan (1st grade): Why [writing’s] fun is because—hmm. I just like it and I think I’m good or something. I just like it.

Interviewer: What kinds of things do you write in school?

Aidan: We write about like poems and stories and stuff. And like our teacher usually reads a book to us or sometimes she doesn’t read a book to us, and she’ll say write a poem about bla bla bla or like something. And so that’s what I like about it.

Aidan’s most specific reason for liking to write in Grade 1 is because the teacher’s writing assignments relate to a book read aloud. By the end of Grade 3, however, he can describe his growing interest in writing in more detail, specifying favorite genres as well as discussing his pleasure in creative self-expression and research:

Aidan: I like to put ideas down on paper and I like to make up stories and stuff. [At home] I made a nonfiction book and I got books from the library and wrote about tigers and elephants. I like to write nonfiction books. And I just write lots of stuff at home. Mostly adventure books, nonfiction, those things.

These increases in complexity were likely due, in part, to children’s experiences with literacy in school and at home. All the teachers in this study made connections between reading and writing, although these varied somewhat in prominence and content. In most classrooms but increasingly with higher grade level, students were exposed to different kinds of texts and invited to produce similar texts. Experiences ranged from writing “patterned stories” (stories with a repeated motif in content and form) in Grades 1 and 2 to reading biographies or histories and then researching and producing their own in Grade 3. When students produced extended texts, teachers often guided the composition by suggesting or specifying topics or genres to be used. Given the opportunity to develop interests in particular topics and genres, along with a vocabulary for describing them, it is not surprising that topic and genre emerged as categories within interest talk in both reading and writing.

Comparison of Salience Across Schools

The proportion of children in each school mentioning various aspects of motivation was calculated, providing a measure of the prevalence or salience of each aspect. Because the two schools drew from different socio-economic strata, it is plausible that differences in the salience of different motives may have been related to the community or family context. Salience differences may also be related to either development of literacy skill or changing classroom contexts. Thus, school by grade crosstabulations were conducted, using likelihood ratios and, where appropriate, Fisher’s exact test for matrices with few or no observations in a particular cell. The analysis cell sizes are shown in Appendix A.

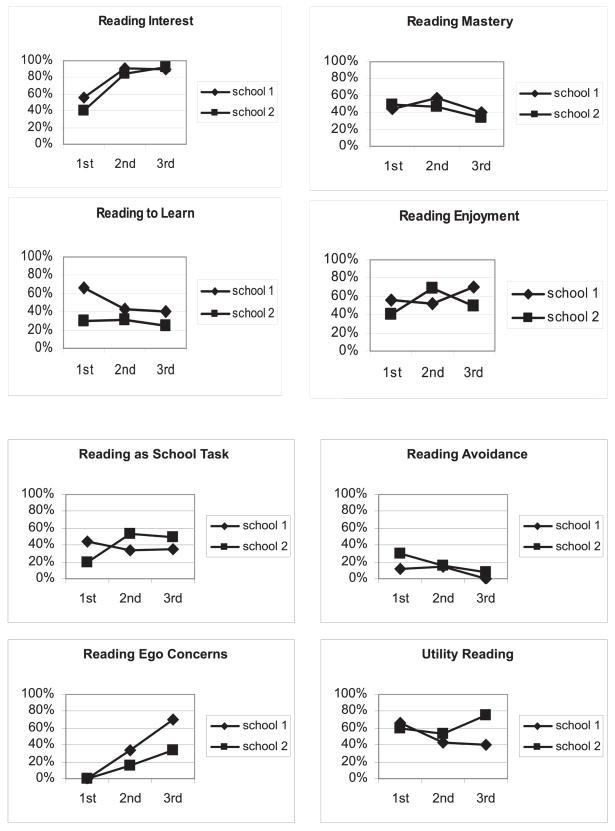

Reading motivation

The proportion of students whose talk about reading was coded into each of six motivational categories is shown in Figure 1. In general, grade-related changes in the salience of motivations to read were similar in the two schools. However, various aspects of what has been termed intrinsic motivation, task orientation, or mastery orientation (see Figure 2) showed changes with age. The proportion of children who talked about interest increased sharply from Grade 1 (47%) to Grade 3 (91%). Mastery concerns trended downward during this period as more children gained fluency, though the motivation to improve reading skill still appeared in over one-third of the interviews. Enjoyment remained fairly stable across years. Extrinsic reasons for reading showed patterns in line with previous developmental work in motivation. Both schools assigned reading as homework, either “reading minutes”(School 1) or “Book-It” (School 2), and the importance of reading for school success was clearly salient in both schools.8

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of children mentioning each type of motivation to read, by school and grade. Note: 1st grade—School 1 n = 9, School 2 n = 10; 2nd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 13; 3rd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 12.

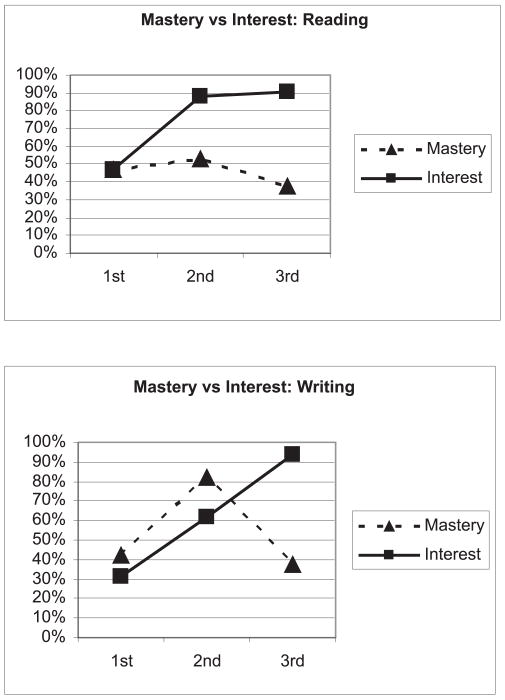

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of students giving mastery and interest as reasons for learning to read and write, by school and grade. Note: 1st grade—School 1 n = 9, School 2 n = 10; 2nd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 13; 3rd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 12.

The salience of ego concerns increased with grade in both schools; there was a significant difference by school and grade in the proportion of students mentioning them. More third graders in School 1 raised ego concerns than in School 2 (likelihood ratio(1) = 4.15, p =.042). This distinction may reflect differences in the community contexts; parents in the high SES school, for example, may have been more active in ensuring their child would be above average. Differences in the salience of ego concerns have also been related to the social context of the classroom, and the social meaning assigned to ability differences.

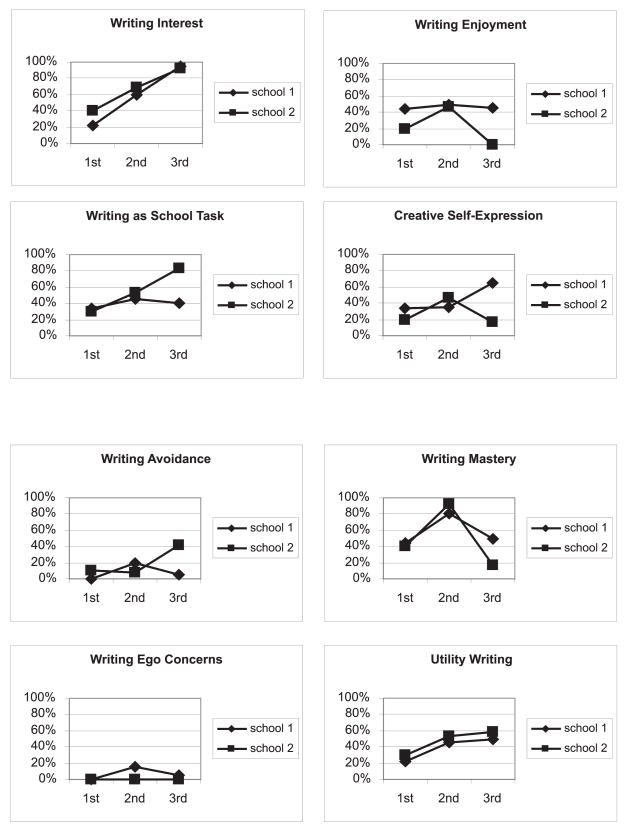

Writing motivation

As was the case for reading motivation, there are similarities between schools in the salience of different motivations to write, shown in Figure 3. In addition to the increase in the proportion of students mentioning interest, there were similar changes across grades in ego concerns, utility, and mastery. In Grades 1 and 2, the proportions of children mentioning each type of motivation is comparable in the two schools; in Grade 2 it is almost identical. Mastery showed approximately the same pattern in both schools, peaking in Grade 2 with the focus on cursive penmanship and dropping sharply in Grade 3.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of children mentioning each type of motivation to write, by school and grade. Note: 1st grade—School 1 n = 9, School 2 n = 10; 2nd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 13; 3rd grade—School 1 n = 20, School 2 n = 12.

Between-school differences in the salience of various writing motivations also appeared in Grade 3, just at the time when most students have mastered handwriting to the point where they can produce text fairly fluently. A higher proportion of third graders in School 1 cited mastery motives (50%) as compared to School 2 (17%), although this was not significant at traditional levels (likelihood ratio = 3.80, p =.051, two-tailed). Writing enjoyment remained constant in School 1, appearing in the interviews of around half the children each year. In School 2, the number of children mentioning the fun of writing declined to zero in Grade 3. Crosstabulation using Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) found this difference to be significant (likelihood ratio =10.50, p =.012). More students in School 2, on the other hand, mentioned avoiding writing (42%), while only 5%—one student—mentioned avoidance in School 1 (likelihood ratio =6.64, p =.018). There were also differences favoring School 1 in the extent to which students talked about creative self-expression (likelihood ratio =7.53, p =.012). The reasons for these differences were explored in the analysis of classroom contexts.

Motivations Developing in School Contexts

The content analysis of children’s interviews, followed by school by grade comparisons of salience, provided the starting point for the ethnographic analysis. They provided a sense of “what develops” in early literacy motivation and provided some hints of possible mechanisms. By analyzing field notes, child interviews, and teacher interviews, the role of classroom context in literacy motivation development was explored. Although children read and write in other contexts, literacy is the focus of activity for hours each day of school. Classrooms are important places to study how developing motivation is related to the nature of literate activity, literacy’s role in social life, and the ways in which meanings and positions were negotiated.

Data Sources

In order to be able to triangulate on the basis of the three data types, the ethnographic analysis focused on two classrooms at each grade in each school in which observations and child and teacher interviews were conducted. Again, the data from children who participated at least 2 of 3 years were examined. (Six children were in other classes where observations and/or teacher interviews were declined.) The sources of data for the context analysis are shown in Appendix A.

Organization of classrooms within the schools

Students from both schools were in multiage classes. In School 1, all students spent Grade 1 with Ms. Adams, which she taught in collaboration with a kindergarten teacher. Ms. Adams taught Language Arts (LA) to all first graders in the combined class. In Grade 2, Ms. Adams’ students were reassigned, and some went to Ms. Bowers’ team-taught 2nd/3rd class. Second graders in this class had LA instruction with Ms. Bowers, although some activities (e.g., literacy groups) were mixed age and cotaught. The students remained together in Grade 3 (taking in a new group of second graders), but restaffing resulted in having a different teaching team. Ms. Donovan was a beginning teacher responsible for the third graders’ LA instruction and cotaught social studies. In School 2, Ms. Norman and Ms. Oliver team-taught a 1-2-3 multiage class, with approximately 16 children in each grade. For LA instruction, Ms. Norman took all first graders and some less-skilled second graders. Ms. Oliver taught rest of the second graders and all the third graders. During Year 2, both teachers were interviewed.

Coding

Field note coding followed the research questions. To examine the role of context in the development of interest, field notes were coded for evidence of student interest, social interaction related to interest, and teacher strategies for promoting interest. To examine differences in the growth of ego concerns in reading, field notes were coded for social comparison events, marginalization of target students, behavior of target students reflecting ego concerns, classroom activity structures that either highlighted or downplayed differences in literacy skill, and teacher strategies for normalizing individual differences. One set of codes, used to examine the differences in the salience of different motivations for writing that emerged at Grade 3, focused on the contexts and purposes for which students wrote, structure of writing tasks, and opportunities for creative control.

Teacher and child interviews were used to check interpretations and to triangulate data. Important data for this purpose included teachers’ descriptions of their literacy goals, the strategies they used, and their descriptions of target students. Student interviews were examined for talk about teacher strategies, sources of their own interest, and ego concerns. The latter were based on their reasons for preferring social versus individual reading and on their interpretation of the small-group reading scenario. Particular attention was paid to target children’s responses to teaching strategies.

An analytical memo was created for each observation, providing a summary of codes and additional description of the observation as a whole. Based on these memos, teacher interviews, and target child interviews, an analytic memo was created for each teacher at each grade. Descriptions of each classroom, based on these memos, are available on the author’s website: http://faculty.washington.edu/sunolen/C&I_classroom_descriptions.html

Classroom Contexts and Reading Motivations

Development of interest in reading: The role of context

Over the three years of the study, reading instruction in both schools changed as children developed skill: phonemic awareness and decoding gave way to fluency and information-finding. In both schools, there was increased emphasis on literary analysis and interpretation, exposure to a variety of genres, and reading for learning and enjoyment. There were also similarities in many of the strategies teachers used to increase children’s motivation to read, including use of good children’s literature, books on interesting topics, emphasizing social aspects of reading, and incorporating art, music, and poetry into communicating about text. Practice in beginning reading skills was usually framed as a game or fun activity. As shown in Figure 2, increasing skill brought with it opportunities to read and to discuss more interesting texts, reducing the concern with mastery and increasing the salience of interest as a motivator in both schools.

Teachers in this study believed that finding interesting activities and texts would lead students to develop a “love of” reading. This is similar to the developmental hypotheses of Renninger, Hidi, and others (Hidi et al., 2002; Krapp, 2002; Lipstein & Renninger, 2006; Renninger & Hidi, 2002) that individual or stable interests develop from triggered and then sustained situational interest. A particularly interesting story, for example, or a class activity where children read to find out more about the Titanic after seeing the movie with family, might trigger a child’s interest and hold it for an hour or a day. If some aspect of the context sustained interest in particular books, genres, or activities over time (e.g., social interaction around books, sharing favorite authors, using the Titanic as a theme relating reading, writing, art, and science), students could develop a more stable interest that might extend to other contexts (e.g., home, the library).

Beginning in Grade 1, aspects of the context in both classes afforded opportunities for this development. Teachers raised student interest by positioning reading and books as interesting, informative, and enjoyable. Early in Grade 1, Ms. Adams introduced a unit on Antarctica, by asking for predictions about “what we’ll find there,” and reading interesting bits out of a book with lots of expression. She encouraged interest through modeling her own. “Oh, my goodness, listen to this!” she gasped, “They think there might be gold there?”.

In both classrooms, lessons and units of instruction were modified or scrapped to capitalize on students’ current fascinations. Students’ writing was also held up as interesting and enjoyable, positioning them as producers of these fascinating objects. In October, Ms. Norman read a funny, high-interest story about animals wearing underwear, then introduced their journal prompt:

(Field notes, October 23) “What do you think I’m going to let you write about in journals today?”

“Underwear!” chorus the kids.

“There’s only going to be one rule: When we write about underwear today, we’re going to write about animals. Do you want to give me some names of animals so I can write them on the board for you?”

Several hands go up. A boy asks if he can put underwear on a pumpkin? Ms. Norman expands the rules to allow animals and plants.

Marsha raises her hand, “Boa constrictors.”

“That word makes me laugh, just hearing it,” smiles T. During journal time, Marsha works on describing her boa constrictor wearing underwear. Others at her table suggest funny ways to show how a snake could wear underwear, having no legs.

Regular opportunities to share good stories, poems, and books also provide the social space to interact around reading. In all the classes in this study, there was a semistructured period of reading self-selected books each day. In Ms. Norman’s and Ms. Oliver’s classroom, this period could involve reading to other children or sharing books. Most children, especially in Grades 1 and 2, referred to this quiet reading period when asked about “reading in school,” rather than to reading lessons. This free-reading period provided a natural context for children to discuss and recommend books they had read, leading to the spread of interest in particular books or (later) series and authors. Both Ms. Adams and Ms. Norman used partner reading to provide social reasons to practice reading.

Karen, a girl in the Norman–Oliver class, exemplifies the development of interest in classroom social context. Karen declared that, “reading is fun” in Grade 1 because she gets to sound out words. However, she did not like to read at home. In Grade 2, Karen’s decoding skills had improved (perhaps related to increased opportunities to read with partners as Ms. Norman emphasized fluency more), allowing her to read more smoothly. (In her interview, Ms. Norman cited feeling competent in reading as one of the main reasons for her focus on fluency.) Although Karen was still vague about what she read at home and school (“Just books, that’s all”), a particular book caught her fancy around the time of the interview. The source of this triggered situational interest was the fact that the title character shared her family name. By Grade 3, Karen had become a fluent reader. She had been introduced to a series of books by a friend; the series was a popular one among children in Oliver’s and Norman’s class. She describes her ongoing interest in that series.

Karen (3rd): I read these books that are really good, they’re a series kind? And it’s really good. It’s different than books I read last year. Because I just read them out of the tubs [of reading books in school] but this was from my friend, she had these books and I read them. And they’re good.

Karen contrasted her current, ongoing interest in a specific group of books to her former, rather random selection of books to read “out of the tubs,” books the teacher provided. The fact that it is a series with the same characters in each book, in combination with the social value of reading and talking about this series, afforded an opportunity to develop a more stable interest.

In both schools, children in the sample moved from describing their interest in specific books to favorite series. Since these were often mystery or fantasy series, other similar books and series were shared among the children. The triggered situational interest in specific stories or books appeared to be sustained by the plots and characters of series and/or by multiple books on specific topics. As librarians, teachers, and parents built on these interests, they seemed to expand into emerging individual interests in particular genres (mysteries, adventures). Based on interview data, 33 of 35 children fit this general pattern of change, although starting at various points in the continuum. In the 22 children mentioning interest in 2 or more years, 12 sustained interests in the same topic or genre. In four cases there was evidence of expanding to interest in multiple genres. Spontaneous sharing of books and series was observed in both schools. The general trend of interest in reading is shown graphically in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Developmental changes in how children talk about reading preferences.

Social meaning, identity, and the development of ego concerns

As children develop, they become increasingly aware of their ability relative to others (Nicholls, 1989). The classroom social context is likely to play an important role in determining the meaning these differences have for children’s status in the group. These meanings and students’ identities are continually co-constructed by teachers, children, and parents through their acts in the classroom and school (Holland, Jr., Skinner, & Cain, 1998; Vauras, Salonen, Lehtinen, & Lepola, 2001). Using longitudinal ethnographic data, it is possible to look for the emergence of these meanings and how reading skill is or is not linked to the development of ego concerns.

The role of helping has been identified as important in negotiating the meaning of skill differences and the positions of less-skilled readers and writers (Berry, 2006). Children who are over-helped or who are always the one receiving help, never providing it, may come to be identified as individuals who have nothing of value to contribute. In Grades 1 and 2 there is a great deal of oral reading, making obvious that some children can read fluently while others must sound out or guess at many words. When a student hesitates while reading aloud to a peer or to a group, questions of power, learning, and group purposes are raised.

Norman–Oliver

In Ms. Norman’s first- and second-grade class in School 2, children were assigned rotating partners for reading practice. To avoid reinforcing less-skilled readers’ identities as incapable, she was careful to shuffle pairs so that sometimes children read with someone of similar skill and other times with peers of higher or lower skill. Lower-skilled second graders were often asked to help younger students, an advantage of the multiage structure. To prevent over-helping, Ms. Norman taught all students coaching skills that emphasized leaving control with the student being helped. The specific decoding strategies taught helped them build their own skills. Jonah, one of the target children, talked about the role of peers in learning to read.

Interviewer: So how did you learn to read?

Jonah: By teachers, other kids helping me to sound out sounds, and mostly by my mom and dad and my teachers and just me sounding out the words…

Interviewer: So your teachers and your mom and dad help you to read?

Jonah: Yeah. And other kids.

Further, both Ms. Norman and Ms. Oliver publicly emphasized that all children could and would improve, and that individual differences were natural and nonproblematic. Ms. Norman especially stressed the importance of practice in the second year. Many literacy activities were framed as opportunities to practice and improve, but the practice-improvement link was highlighted across the spectrum of important skills:

(Field notes, February 22) 10:07 Ms. Norman finds Fred over at Jonah’s table, getting advice from Jonah on his drawing. She guides Fred back to his desk. “You know, Jonah is a really good artist, but so are you. And you will get better with practice. Maybe during center time you can ask Jonah about this.”

Ms. Norman’s and Ms. Oliver’s emphasis on practice and improvement reinforced the normative view that individual skill differences were normal and nonthreatening. The message given to students was that all children could improve through practice. The children themselves talked about individual differences in a matter-of-fact way, focused on learning. In his Grade 2 interview, Jonah responded to the question “How’s reading this year?” with “Well, I really, really improved on it. Before—I’m still struggling but I think I can get better and I feel like I’m learning more.” The following year, Jonah again began by describing his own improvement: “A lot better. Almost up to Grade 3 level.” Asked about reading aloud to the whole class, he described his peers as supportive:

“Well… I can’t really explain it. I mean, sometimes I skip words, no one laughs, I’m having trouble, but they know I’m getting better. Because they know that me and Scott have trouble, but they know we’re getting a lot better…”

Beliefs about ability differences also surfaced when students talked about the round-robin reading group scenario. Student interviews in Norman and Oliver’s classroom suggested that children had adopted these promoted beliefs. This adoption is reflected in second-graders’ response to the round-robin reading scenarios and the struggling reader:

Interviewer: How do you think the other kids feel about having this boy in their group?

Tom: That he needs like more work so it’s kind of good to read like that sometimes, if someone needs work.

Abigail, a slower reader herself, reflects the teachers’ message that individuals will differ in various abilities, and that these differences do not translate into inferiority or superiority:

Interviewer: How do you think these kids feel about having this girl in their group?

Abigail: Happy. Because she’s just as smart as they are.

Adams–Bower

In School 1, Ms. Adams and Ms. Bower both encouraged students to help each other, but did not specifically focus on normalizing individual differences nor did they teach coaching strategies. Ms Adams’ students suggested “help with the word” or “help sound it out” as strategies for helping, most likely based on their own experiences. When the interviewer described the reading group scenario to Ms. Bower’s second graders, 6 of 14 students suggested that the other children should just “give her the word” (pronounce “knelt” for the struggling reader). Observational data confirmed that “giving the word” was the strategy of choice when reading aloud in mixed groups, often before the slower reader had a chance to try decoding the word.

Most children in Ms. Bowers’ class also believed that the others would not like having a struggling reader in the group. Without an emphasis on practice leading to improvement, fluent students did not see themselves as important contributors to that improvement. In addition, the stress early in Grade 2 on finishing before recess positioned slower readers as obstructions to pleasure. The slower readers were well aware of this view.

Carl, one of several poor readers in the class, suggested the fluent readers should explain the silent K rule rather than give the word, so the struggling reader could learn. When asked why the other children might just give him the word, Carl explained the social situation and possible consequences:

Carl: Maybe because they get frustrated. About him not reading fast enough.

Interviewer: That could be. How do you think he’d feel about that?

Carl: Probably pretty bad. Because it’s like it’s having somebody like yelling at you for something you can’t help.

Interviewer: So we don’t know what they’d do, but how do you think they’d feel about having that boy in their group?

Carl: They would probably not really like—they might like him but they might not because maybe they have to like do it in a certain time and maybe he can’t read it fast enough so they had to stay in [at recess time]. So they might get really angry at him and never want to have him again.

In Ms. Bower’s class, reading preceded recess, and at the beginning of the year, children were usually required to finish reading work before they could play. In Normans’ and Oliver’s class, this was done rarely. Comparing second-graders’ responses in the two classrooms, almost all (93%) of Ms. Bower’s students stated that the other members of the group would feel “bad” about having a struggling reader in their group compared to 69% of students in the Norman–Oliver class, but this difference was not statistically significant (X2 = 3.39, p = .084). However, there was a significant difference in the number of students who thought the others would like having a struggling reader in their group: 54% of the Norman–Oliver students, compared with only 13% of Ms. Bower (X2 = 4.09, p = .043).

Ms. Bowers was never comfortable in withholding recess, and stopped using this consequence by mid-year. She also started emphasizing that students had time or could take the time needed to do the work. The interview data suggest that value of quick reading persisted despite her efforts to influence the meaning of slower work. Other aspects of the context likely helped maintain the devaluing of slow reading and marginalization of slower students.

Ms. Bowers and her partner decided earlier in the year that small groups needed an adult leader, and parent volunteers generally provided this assistance. Unlike Norman, however, neither Adams nor Bowers was observed to have trained parent volunteers in coaching strategies. Like the faster readers, the parents also over-helped, supplying words at the least sign of hesitation, rather than promoting learning by coaching or providing time for the child to try reading him or herself. Parents also modeled impatience with slow readers, as in the following observation from field notes:

(Field notes, March 24) Bowers (2nd) Great Books group, led by an adult volunteer.

The adult (a parent) asks Glen (a target student) to read first. “Do you feel like a competent reader?”

Glen looks puzzled. “What?”

“Are you feeling like a good reader today?”

Glen asks, “Do I have to?”

“I’d like you to,” responds the adult.

It is not clear why the adult raised competence concerns so publicly at the beginning of the round-robin reading. Glen’s response suggests that this concern is unexpected, and may be connected to his attempt to avoid reading aloud.

Glen starts reading aloud. When he hesitates, the adult supplies the word. Sometimes one of the students does, too. Glen reads most words slowly, with little intonation. He stumbles on “buggy.” Right at the end of the last sentence, the adult steps in.

“That’s good, Glen. Arnie do you want to read?”

“Can I read two pages?” asks Arnie eagerly.

Glen asks, “Do I have to read any more?”

“No,” responds the adult, “You did fine. You don’t have to read any more.”

As the other kids read, Glen follows along in his book, using a bookmark to mark his place. The other kids in the group read much more fluently than Glen, until it is Sally’s turn. Sally reads slower than Glen, stumbling frequently over words. Every time she hesitates, the adult and other kids supply the word. After a sentence or two, the adult stops her and says she (adult) will finish for her.

Sally protests, “But I want to read it!”

“You can read it later,” says the adult. “But I want to have a little teeny discussion about this part, so… (starts reading)”

When no one asks children if they want help with their reading, it is nearly impossible to avoid the usurpation of reading rights. Opportunity to read was a common reason for children to choose “reading alone” over “partner reading” or “group reading.” It also allowed “reading in my head” and less-frequent interruption by others. But even when directed to read in groups, target students in Ms. Bowers’ class resisted being marginalized. Withdrawing from the task (without leaving the group) was a common strategy. After being over-helped and shut out of a discussion about the Great Book her group was reading, Georgia physically withdrew by scooting her chair back a few inches. Target children also fought back by acting out, being silly, or refusing to answer questions. When the parent leading Georgia’s group asked her questions later in the lesson, she resisted:

(Field notes, March 24) Leading the discussion, the adult asks the group, “Why did Bubber question this?”

Georgia responds, “Maybe he doesn’t want to be weird.”

The adult doesn’t pay any attention to this, talking mostly with the two children next to her. When the adult asks another question, Georgia says, quickly, “I don’t know.”

The adult probes, “Do you remember the conversation?”

“Yes,” replies Georgia, grinning. Discussion moves on, still the adult and the two kids doing most of the talking.

Unfortunately, these resistance strategies have their costs. When students withdraw or act out, they reduce opportunities for skill improvement while reinforcing their identities as difficult students. “Silly” behavior can result in teacher sanctions or lead to peer rejection. With one exception, target children were accepted socially (as evidenced by playground observations and teacher reports). However, over the 3 years of the study, reading and writing skill gradually replaced friendship as the main criterion for selecting reading/writing project partners.

Resistance can also have more positive outcomes; it is a way to alert teachers to problems. When Ms. Bowers began to notice withdrawal behavior, she asked me to include three students with low reading and writing skills in my target group. Based in part on my initial observations, she identified aspects of the context that might privilege reading speed (e.g., the requirement to finish before recess, her own statements about time constraints) and addressed those.

For the children who spent Grade 2 with Ms. Norman’s group, the transfer to Ms. Oliver’s presented some challenges. After spending a year positioned as older, more able readers, they moved into a position of being the low-skilled ones. The pace of lessons was faster, the texts more difficult, and the expectations higher in this new LA setting. The three target children negotiated new positions with the students and teacher over the course of the year. Marsha was the best reader in Ms. Norman’s class during Grade 2 and enjoyed the leadership position this status afforded. Since kindergarten, Marsha regularly “played school” with friends, particularly relishing the teacher role. In her new class, Marsha negotiated a leadership position during many small group activities by surrounding herself with Grade 2 girls. Scott became more withdrawn during large-group work, except for lessons where he could contribute actively. In small groups, he began to run into problems when others had to wait for him to finish:

February 16. When I turn back the boys are challenging Scott on whether here members anything from his reading. “OK, I remember something. I remember that…(can’t catch).” Scott is grinning. He points something out in the book, distracting them. They get into a mutual demonstration of ways to cough and clear one’s throat.

Scott was well-liked by the others, and seemed to capitalize on this popularity by smiling and joking in situations like this one. When the Norman–Oliver class worked on projects together, Scott was observed as trying to direct younger students’ work, perhaps trying to recapture his former position.

Ms. Oliver, like Ms. Norman, used small, flexible reading groups to prevent students from being stigmatized. She worked to support less-skilled readers and encouraged others to do the same. In practice, this strategy may have positioned less able readers as having lower status, as in the following excerpt from field notes:

9:40 In reading group, Ms. Oliver reprimands Jonah for not paying attention. “You need to follow when Tom reads. He’s an excellent reader.” Jonah follows industriously after that… “Now Jonah, what I want you to do is, now that you’ve heard me read this paragraph, you go back and read it out loud.” Jonah reads slowly, about half to three-quarters as fast as Tom. When he’s finished, the teacher says to the other two children, “What did you think of Jonah’s reading? That was really good reading.” They look noncommittal.

Summary

Classrooms across schools shared common practices that increased children’s interest and motivation in reading. Teachers provided ways to see reading as an opportunity for enjoyment and learning, even phonemic awareness and penmanship practice was framed as a game by the two Grade 1 teachers. Adams and Norman especially followed students’ changing interests to frame lessons and units. All teachers built in opportunities for social interaction around books. Students exchanged books and recommendations, spontaneously discussed books and stories they were reading, and shared favored books during partner reading. These similarities are reflected in the similar patterns in the salience of positive-reading motivations across schools.

Classrooms differed in the kinds of identities afforded for less-skilled readers and in the role reading skill played in social status. Aspects of the social context that appeared particularly important in the development of ego concerns included how classroom communities socially constructed the meanings of skill differences. Certain activities were noted to contribute to the rise of ego concerns in both schools, including the actions of peers and adults in supporting skill development and positioning children as readers or nonreaders; the presence or absence of specific, shared coaching strategies; and the constraints on reading time.

Classroom Contexts and Writing Motivations

As shown in Figures 3(a) and 3(b), the salience of the various motivations was similar across the two schools in Grades 1 and 2, but a number of differences emerged in Grade 3. These patterns reflect, in part, a set of relationships in each context: the position writing enjoyed in each classroom community and the function it served, the extent to which the context supported sustained interest and enjoyment, and the development of writing skill.

In Grades 1 and 2, both teachers stressed that their main goal in writing was for students to gain confidence in their ability to communicate ideas in writing. For some, this process started at learning to produce single letters, although most were using invented spellings to write sentences and others were already writing notes and cards to friends and family. The positioning of writing as a tool for expression and communication was accomplished through a variety of writing tasks and frequent sharing of work with others. Children wrote frequently in both classes, usually about an interesting topic. Standard topics were writing about their own lives or experiences, writing about interesting classroom activities, writing to extend stories or patterned books, and writing letters and notes. Spelling and mechanics were gradually introduced, but the point of writing was always creative expression or communication. Both teachers frequently read aloud (or had children read aloud) their stories and poems and provided positive comments that pointed out techniques that made the writing interesting.

In Grade 2, this pattern continued in Ms. Norman’s room. Children kept journals and wrote in them daily on a variety of topics. There was always support for choice and creativity; when the journals began to be used for other kinds of expression (e.g., drawings, notes), Ms. Norman had children create a second “journal” that was for students’ purposes alone. Ms. Bowers used some of the same interesting activities (e.g., pattern stories, extensions of carefully selected interesting or enjoyable books); both teachers scaffolded composition and used brainstorming to generate interest and ideas. Brainstorming was especially important for those children who often had a hard time coming up with their own ideas for writing. Writing assignments included some choice, but tended to be more teacher-directed in Bowers’ class, where children did more independent practice on syllable structure and other literacy tasks. More scripted writing and the usually single-task structure made social comparison easier in Ms. Bowers’ than in Ms. Norman’s class, where multiple-task structure was more common.

Writing instruction in the two Grade 3 classes was similar in some respects, with elements of Guthrie’s suggestions for intrinsically motivated contexts for reading (Guthrie & Alao, 1997; Guthrie & Knowles, 2001): both teachers integrated their writing instruction with social studies content and historical research, and both allowed for student collaboration and provided some interesting texts. Both teachers also taught grammar and composition strategies, and both used “Daily Oral Language” exercises in which students found and corrected teacher-generated errors in grammar, spelling, and punctuation. In both classes there was a year-end class goal of producing writing for a real audience.