Abstract

There are three enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the adrenal androgen dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) sulfate. Cholesterol side-chain cleavage (CYP11A1) and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17) metabolize cholesterol into DHEA, whereas steroid sulfotransferase family 2A1 (SULT2A1) is responsible for conversion of DHEA to DHEA sulfate. We previously examined the mechanisms regulating CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 transcription and found that each is regulated, in part, by the transcription factor GATA-6. Previous studies suggested that mediator complex subunit 1 (MED1, also called PPARBP or TRAP220) is a cofactor involved in not only the regulation of nuclear receptors but also the activation of GATA-6 transcription. Herein we demonstrated a role for MED1 in the regulation of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 transcription. Transient transfection assays with SULT2A1 deletion and mutation promoter constructs allowed the determination of specific the GATA-6 binding cis-regulatory elements necessary for transactivation of SULT2A1 transcription. Binding of MED1 and GATA-6 was confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation/Western analysis and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. We demonstrated expression of MED1 mRNA and protein in the human adrenal and determined that knockdown of MED1 expression via specific small interfering RNA attenuated CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 expression levels in H295R cells. In addition, we demonstrated that MED1 enhanced GATA-6 stimulated transcription of promoter constructs for each of these genes. Moreover, the activity of MED1 for SULT2A1 promoter was mediated by GATA-6 via the −190 GATA-binding site. These data support the hypothesis that MED1 and GATA-6 are key regulators of SULT2A1 expression, and they play important roles in adrenal androgen production.

Mediator complex subunit 1 is expressed in the human adrenal and plays a role in the regulation of enzymes involved in adrenal androgen biosynthesis.

The production of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) within the adrenal cortex relies on three steroid-metabolizing enzymes. Cholesterol side-chain cleavage (CYP11A1) and 17α-hydroxylase/ 17,20-lyase (CYP17) are involved in the conversion of cholesterol to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (1). CYP11A1 performs the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, whereas CYP17 catalyzes the 17α-hydroxylation of pregnenolone and, subsequently, the 17,20-lyase reaction on its 17α-hydroxy derivative to DHEA. CYP11A1 and CYP17 are expressed in both the zona fasciculata (ZF) and zona reticularis (ZR) of the human adrenal cortex (1). On the other hand, steroid sulfotransferase family 2A1 (SULT2A1), commonly known as steroid sulfotransferase, has been localized by immunohistochemistry to the DHEA-producing adrenal ZR, in which it catalyzes the conversion of DHEA to DHEAS (1,2,3). Although the enzymatic activity of SULT2A1 has been studied in some detail, little is known about the regulation of human SULT2A1 expression. We previously reported the role of three transcription factors, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1 or NR5A1), GATA-6, and estrogen-related receptor-α (or NR3A1) in the regulation of SULT2A1 transcription (4,5). However, the potential for transcription factor coactivator enhancement of adrenal ZR SULT2A1 expression has not been studied.

The mediator complex subunit 1 (MED1; also called PPARBP or TRAP220) was originally identified as a coactivator for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ but later shown to participate in the transactivation of other nuclear receptors (6,7,8,9,10,11). In addition, it is suggested that MED1 is a cofactor involved in not only the activation of nuclear receptors but also the activation of other groups of transcription factors (6). Crawford et al. (6) demonstrated that MED1 interacts with five GATA family transcription factors, including GATA-4 and GATA-6. The MED1 coactivator activity was independent of the nuclear receptor recognition sequence motif LXXLL, in which L is leucine, and X is any amino acid (6). GATA-6 is highly expressed in the adult and fetal adrenal cortex and is capable of regulating transcription of steroidogenic enzymes, including CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 (12,13,14). Saner et al. (4) previously reported that GATA-6 is a positive regulator of SULT2A1 transcription through a GATA-binding site in the proximal promoter.

Whereas MED1 is widely expressed in normal and tumor tissues, its potential role in the adrenal gland has not been examined (8,15,16,17,18,19). Herein we demonstrated that MED1 was expressed in the human adrenal gland and that it enhanced adrenal cell CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 gene expression. MED1 enhancement of SULT2A1 was through interactions with GATA-6, which bound to its respective response elements on the regulatory region of the SULT2A1 gene. The current study supports a potential role for MED1 in the regulation of adrenal DHEAS production.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue attainment

Human adult adrenal gland, brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, premenopausal ovary, salivary gland, skeletal muscle, and thymus were obtained through the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (Philadelphia, PA), CLONTECH (Palo Alto, CA), University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX), and Tohoku University School of Medicine (Sendai, Japan). The use of these tissues was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Medical College of Georgia (Augusta, GA), and Tohoku University School of Medicine.

Cell culture

The human adrenocortical cell line (H295R) was used for all transfection experiments and was routinely cultured in DMEM/Ham F12 medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2.5% Ultroser G (Life Sciences, Cergy, France), penicillin, streptomycin (Life Technologies), gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1% insulin, human transferrin, selenious acid + universal culture supplement premix (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) (20). HEK293T cells were routinely cultured in DMEM/Ham F12 medium (Life Technologies, Inc.), 10% cosmic calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), and antibiotics consisting of penicillin, streptomycin, and gentamicin.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR)

The protocol for cDNA synthesis was previously described in detail (21). We measured the relative expression levels of MED1 mRNA in H295R cells and human tissues described above. Analysis of MED1 was performed using primers and probes from TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). qPCRs were performed using the ABI 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative normalization of cDNA in each tissue-derived sample was performed using expression of 18S rRNA as an internal control. Transcript expression was normalized as previously described (21).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on serial sections of adrenal tissue, using the streptavidin-biotin amplification method using a U.T.R. Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Antibodies used included SULT2A1 (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), GATA-6 (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and MED1 (rabbit polyclonal, kindly provided by Dr. R. G. Roeder, Laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Rockefeller University, New York, NY) (9). Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in a microwave oven for 15 min in citric acid buffer [2 mm citric acid and 9 mm trisodium citrate dehydrate (pH 6.0)]. The dilutions of the MED1 and GATA-6 primary antibodies used in this study were 1:200. The antigen-antibody complex was visualized with 3.3′-diaminobenzidine solution [1 mm 3.3′-diaminobenzidine; 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6); and 0.006% H2O2] and counterstained with hematoxylin. For positive control, a normal rat liver section was used (19). For negative control, normal rabbit or mouse IgG was used instead of primary antibodies.

Transfection of MED1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and examination of adrenal steroidogenic enzyme expression in H295R cells

siRNA of MED1 was commercially obtained from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). As a negative control, Stealth RNA interference (RNAi) negative control duplexes were also used (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Electrical transfection assays were performed using the Nucleofector system (AMAXA, Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, H295R cells were cultured to 80–90% confluence in growth medium and then trypsinized and resuspended in Nucleofector Solution R (AMAXA) at a ratio of 5 million cells per 100-μl solutions. Indicated amounts of MED1 siRNA or Stealth RNAi negative control duplexes (100 nm at final concentration) were added to the solution, and the mixture was run under program T20 in the Nucleofector system. Cells were allowed to recover for 48 h before treatment. Both RNA and protein were isolated from the cells for qPCR and Western analysis. For qPCR, primers and probes for the amplification of the selected human SULT2A1 sequence were done using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems). The primer/probe sets for human steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), CYP11A1, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD3B2), CYP17, and 21-hydroxylase (CYP21) were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). For Western analysis, a polyclonal human anti-MED1 (Abcam) and a monoclonal human anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. In addition, after transfection, the cells were incubated for 72 h and then incubated for 6 h in a low-serum medium containing 0.1% cosmic calf serum and 10 μm 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (Sigma). The medium was collected for DHEA measurement using ELISA (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) and DHEAS measurement using RIA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX).

Preparation of reporter constructs and expression vectors

The 5′-flanking DNA from the human genes for CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 were inserted upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the reporter vector pGL3basic (Promega, Madison, WI) (4). Mutations to the previously defined GATA-binding site (−190) in the SULT2A1 promoter were created by completely removing this site with a −332 deletion construct. Empty pGL3basic served as the control vector to measure basal reporter activity in all transfections. The human MED1 vector was also kindly provided by Dr. R. G. Roeder (Laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Rockefeller University, New York, NY) (9). The construct pMALT, encoding the full-length human GATA-6, was a gift from Dr. Christopher Gove (King’s College, London, UK) (22). The plasmids for GATA-6 short (MYQ) and long form (M147L) have been described previously (4).

Transfection study

Transient transfection assays were performed using Transfast (Promega) in a ratio of 4 μl Transfast per microgram of DNA and the indicated amounts of expression vectors. Cells were harvested 24 h after recovery and assayed for luciferase activity using the luciferase assay system (Promega). To normalize luciferase activity, cells were cotransfected with 50 ng/well of β-galactosidase plasmid (Promega).

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western analysis

H295R cells were grown to confluence on 10-cm dishes and lysed by passive lysis buffer (Promega). After centrifugation, supernatant was then incubated with Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (catalog no. sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h. After centrifugation, supernatant was then incubated with Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose and a polyclonal MED1 antibody for 24 h. The pellets were washed four times. The isolated protein complexes were denatured for 5 min at 95 C and followed by Western blotting analysis with the polyclonal GATA-6 antibody at a 1:200 dilution.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed using H295R cell lysates; EZ-ChIP (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA), MED1 polyclonal antibody, and GATA-6 polyclonal antibody. DNA was diluted into 20 μl of nuclease-free water, and 5 μl were used for each PCR of 32 cycles. The PCR primer sequences were designed based on a previous report showing the primary GATA-binding cis-element in the SULT2A1 promoter region (−190 site) (4). The PCR primer sequences used were as follows: SULT2A1 promoter, forward, 5′-ACTCTCAGGAACGCAAGCTC-3′, reverse, 5′-ACCTTGTCCCAGCATGTCAC-3′. Products were then separated on a 4% agarose gel for detection of promoter region amplification.

Statistical analysis

Results are given as the mean ± se where appropriate. Statistical analyses were done by unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc test for comparisons between two groups dependent on the data types. Significance was accepted at the 0–0.05 level of probability (P < 0.05).

Results

Human adrenal tissue expresses MED1 mRNA and protein

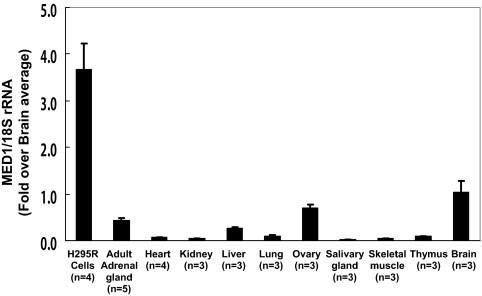

qPCR was performed using mRNA isolated from several types of human tissues and H295R cells (Fig. 1). The level of MED1 transcript was significantly higher in H295R cells compared with all other human tissues that were examined (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). The expression level of MED1 mRNA was not significantly different among human tissues examined in this study (Fig. 1). It is likely that MED1 mRNA is widely expressed in human organs including both steroidogenic and nonsteroidogenic tissues.

Figure 1.

Quantification of MED1 transcript levels in human tissues and H295R cells. Levels of MED1 mRNA were compared in human adult adrenal gland, brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, premenopausal ovary, salivary gland, skeletal muscle, thymus, and H295R cells using qPCR and normalized to 18s rRNA. Data points are expressed as the fold over the average expression levels seen in the brain (19). The level of MED1 transcript was significantly higher in H295R cells compared with any types of human tissues that were examined (P < 0.05). However, the expression level of MED1 mRNA was not significantly different among human tissues examined.

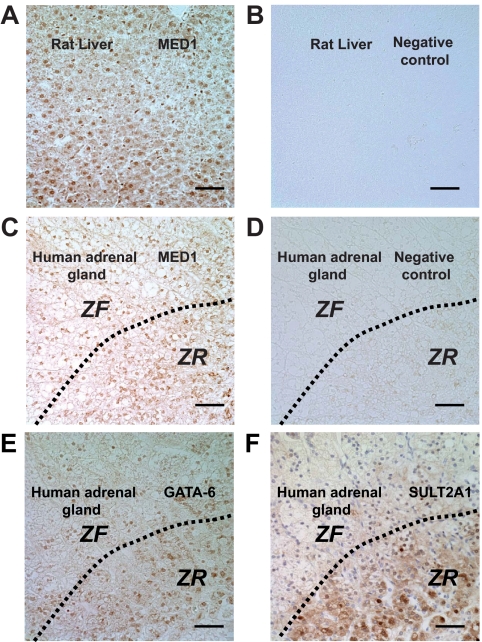

MED1 immunoreactivity was examined in rat liver (positive control) and human adrenal gland (Fig. 2). MED1 immunoreactivity was detected in nuclei of both the liver and adrenocortical cells, including ZF and ZR (Fig. 2C). No staining was observed in the absence of MED1 antibody (Fig. 2D). We also confirmed that GATA-6 was expressed in both the ZF and ZR (Fig. 2E), whereas SULT2A1 was predominantly expressed in the ZR (Fig. 2F), consistent with previous reports (4,23).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of MED1 in the human adrenal gland. MED1 immunoreactivity was detected in the nuclei of rat liver cells (positive control) (A). As a negative control, primary antibody was replaced with buffer only, and no specific immunoreactivity was detected in liver cells (B). MED1 immunoreactivity was also detected in the nuclei of cortical cells of the adrenal cortex (C). When primary antibody was replaced with buffer alone, there was no specific immunoreactivity (D). Immunohistochemical analysis of GATA-6 (E) and SULT2A1 (F) in human adult adrenal gland. Bar, 10 μm.

Effects of MED1 down-regulation on adrenal cell steroidogenic enzyme transcript levels and steroid production

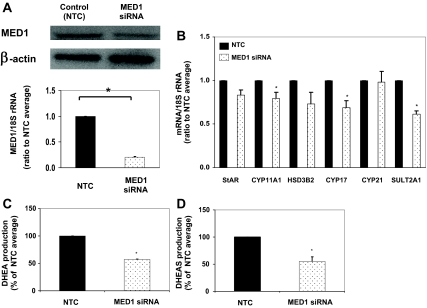

To determine whether MED1 plays a role in the expression of steroid-metabolizing enzymes, we used siRNA to decrease its expression in H295R adrenal cells. Seventy-two hours after transfection of H295R cells with MED1-specific siRNA, the levels of MED1 mRNA dropped by 80% and protein level by 40%, compared with control cells (NTC) (Fig. 3A). SULT2A1 mRNA levels were significantly decreased by 40% in the H295R cells after MED1 siRNA transfection (Fig. 3B). CYP11A1 and CYP17 mRNA levels were also significantly decreased in the H295R cells after MED1 siRNA transfection (Fig. 3B). StAR, HSD3B2, and CYP21 mRNA levels did not significantly decrease afterMED1 siRNA transfection (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of siRNA depletion of MED1 on the transcript levels of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes. A, H295R adrenal cells were transfected with or without siRNA against MED1 (MED1 siRNA) or Stealth RNAi (negative control; NTC). After 48 h, mRNA and protein for MED1 were detected by qPCR and Western analyses, respectively. 18S rRNA and β-actin protein were used for normalization. Data are presented as mean ± se for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. B, Transcript levels for adrenal steroidogenic enzymes were determined using qPCR. StAR, CYP11A1, HSD3B2, CYP17, CYP21, and SULT2A1 mRNAs were examined 48 h after H295R cells were transfected with or without siRNA against MED1 (MED1 siRNA) or Stealth RNAi (NTC). Data are presented as mean ± se for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. C and D, Production of DHEA (C) and DHEAS (D) by H295R cells 72 h after MED1 siRNA transfection. To examine the capacity to produce DHEA and/or DHEAS, cells were treated with MED1 (MED1 siRNA) or Stealth RNAi (NTC). After this treatment, the cells were incubated for 6 h with 10 μm 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol. Data are presented as mean ± se of values from three independent experiments and expressed as a percent of NTC. *, P < 0.05, compared with NTC.

To examine the effects of MED1 knockdown on H295R cell production of DHEA and DHEAS, cells were incubated with 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (10 μm) for 6 h. This steroid precursor is rapidly metabolized by steroidogenic cells and provides a measure of steroidogenic capacity (24). Seventy-two hours after transfection of cells with MED1 siRNA, there was a decrease in the production of both DHEA and DHEAS (∼40% for each) (Fig. 3, C and D).

MED1 activates the transcription of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1

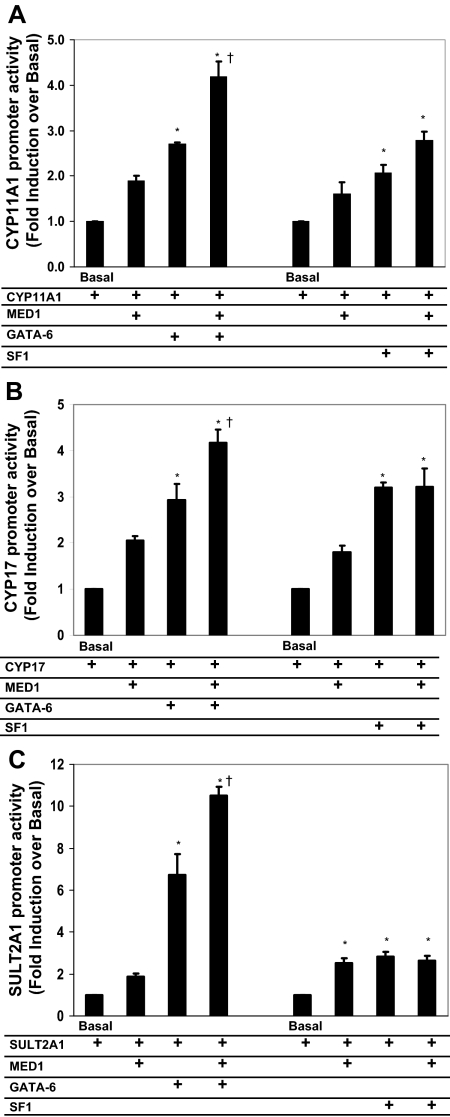

We previously showed that transcription of SULT2A1, CYP11A1, and CYP17 are increased by GATA-6 and SF-1 (4,13). To determine whether these genes were regulated by MED1 with GATA-6 or SF-1, we used promoter constructs for each of these steroidogenic genes in transient transfection of H295R cells. We cotransfected each of the reporter constructs with SF-1 or GATA-6 alone or in combination with MED1. Compared with transfected SF-1 alone, there was no significant additive effect of MED1 on the induction of any of the reporter gene activities (Fig. 4). However, GATA-6 showed an additive stimulation of reporter gene activities for CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 when cotransfected with MED1 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the effects of MED1 and GATA-6 or SF-1 on the transcriptional activity of CYP11A1 (A), CYP17 (B), or SULT2A1 (C) reporter gene activity after transfection with reporter gene constructs. Luciferase promoter constructs containing CYP11A1, CYP17, or SULT2A1 (1 μg/well) was cotransfected in H295R cells with MED1 expression plasmid (0.1 μg/well) and GATA-6 plasmid (0.1 μg/well). H295R cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Data were normalized to cotransfected β-galactosidase expression vector, and data are expressed as fold induction over basal reporter. Results represent the mean ± se of data from at least three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05, compared with basal level; †, P < 0.05, compared with only GATA-6-transfected group.

Both isoforms of human GATA-6 increases SULT2A1 gene transcription with MED1

It has been reported previously that both the human and mouse genomes have two isoforms of GATA-6, which use two distinct promoters and initiation codons (22). Both isoforms are present in the fetal and adult mouse tissues in which GATA-6 is normally present (25,26). In humans, both the long and short isoforms of GATA-6 are highly expressed in ovarian theca cells and adrenal cells (4,27).

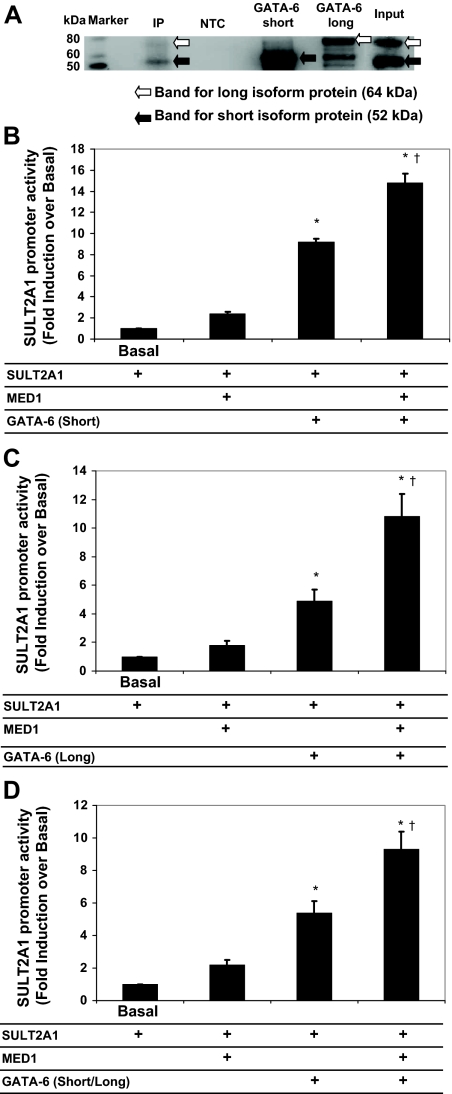

Our Western analysis demonstrated that input of H295R cell nuclear protein had both the long and short GATA-6 proteins, with the short isoform being the predominantly expressed protein, as previously reported (Fig. 5A) (4). In our coimmunoprecipitation and Western analysis, the complex of cell lysates and MED1 antibody could detect distinct bands that corresponded to both short and long GATA-6 isoforms (Fig. 5A). However, the negative control with nuclear extract of H295R cells and rabbit IgG instead of MED1 antibody did not lead to distinct bands for either isoform (Fig. 5A). The results indicate that MED1 interacts with both short and long isoforms of GATA-6 in H295R cells (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Comparison of GATA-6 isoforms on MED1-enhanced SULT2A1 gene transcription. A, Coimmunoprecipitation with nuclear extract of H295R cells using a MED1 antibody. The complex of cell lysates and MED1 antibody (IP) allowed detection of distinct bands for both short (52 kDa) and long (64 kDa) GATA-6 isoforms, which were also seen in the input sample (input). The negative control (NTC) was prepared with nuclear extract of H295R cells and rabbit IgG instead of MED1 antibody. In vitro-prepared short isoform (GATA-6 short) and long isoform (GATA-6 long) represented lysates obtained from H295R cells that had elevated expression of each isoforms after transient transfection with the respective expression vector and acted as positive controls. B–D, In vitro-prepared short isoform (GATA-6 short), long (GATA-6 long) isoform, and both short and long isoforms (GATA-6 short/long) proteins were also included as positive controls. MED1 effects on SULT2A1 reporter gene activity with GATA-6 short (B), GATA-6 long (C), or GATA-6 short/long (D) isoforms are shown. Luciferase promoter constructs containing SULT2A1 (1 μg/well) were cotransfected in H295R cells with MED1 expression plasmid (0.1 μg/well) and GATA-6 short (B), GATA-6 long (C), or GATA-6 short/long (D) isoforms plasmid (0.1 μg/well). Cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Data were normalized to cotransfected β-galactosidase expression vector, and data shown are expressed as the fold induction over basal reporter. Results represent the mean ± se of data from at least three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05, compared with basal level; †, P < 0.05, compared with only GATA-6-trasfected group.

To determine whether MED1 increased SULT2A1 transcription by either the long or short isoforms of GATA-6, we cotransfected the SULT2A1 reporter constructs with both isoforms of GATA-6 in combination with MED1. Transient transfection analyses were performed in H295R cells, with expression vectors encoding either the long isoform (MALT), the short isoform (MYQ), or a mutated form that could encode only the long isoform (M147L). Both forms of GATA-6 additively stimulated transcription of SULT2A1 with MED1 (Fig. 5, B–D).

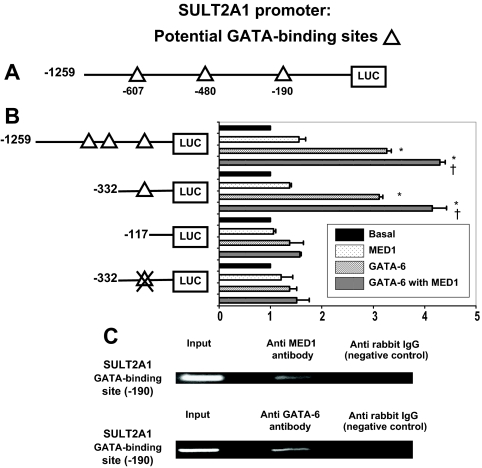

MED1 enhances SULT2A1 transactivation by GATA-6 via a specific DNA binding site on the SULT2A1 promoter

We previously reported that GATA-6 transactivation of SULT2A1 was lost only when the −190 GATA-binding site was deleted or mutated. In this study, we used both deletion and mutation analysis to determine whether the −190 GATA-binding site was necessary for optimal MED1 activation of SULT2A1. As in our previous study, transient transfections were done in HEK293T cells to avoid interactions with adrenal cell SF-1 (13). We demonstrated that deletion or mutation of the −190 GATA-binding site blocked transactivation of SULT2A1 by GATA-6 alone and with MED1. This suggests that the −190 site was necessary for MED1- and GATA-6-mediated activation of SULT2A1 gene transcription (Fig. 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

The role of the −190 GATA binding cis-element in the regulation of SULT2A1 transcription. A, A schematic representation of SULT2A1 promoter with potential GATA binding sites. Triangles represent potential binding sites, and the numbers below represent the base pair at which the site begins (based on the translational start site). B, Deletion and mutation analysis in HEK293T cells. A series of pGL3 reporter constructs containing progressively smaller amounts of SULT2A1 5′-flanking DNA (1 μg/well) were cotransfected in HEK293T cells with MED1 expression plasmid (0.1 μg/well) and GATA-6 plasmid (0.1 μg/well). Data were normalized to cotransfected β-galactosidase expression vector. Results represent the mean ± se of data from at least three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05, compared with basal level; †, P < 0.05, compared with the GATA-6 only transfection group. C, ChIP assay using H295R nuclear lysate demonstrated a distinct band corresponding to the −190 site of the SULT2A1 promoter (input). Immunoprecipitation with either GATA-6 or MED1 antibodies showed that both proteins were associated with the −190 site in the SULT2A1 promoter. ChIP assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

The binding of MED1 to the SULT2A1 promoter region was demonstrated using ChIP assay in H295R cells. ChIP assay using MED1 antibody demonstrated interaction with the −190 site in the SULT2A1 promoter (Fig. 6C). ChIP assay without antibody (negative control) did not show the band corresponding to MED1 (Fig. 6C, upper panel). MED1 is known to lack a DNA binding domain (6). However, we have previously shown that GATA-6 directly binds the SULT2A1 promoter (4). In this study, ChIP assay using GATA-6 antibody also demonstrated interaction with the −190 site in the SULT2A1 promoter (Fig. 6C, lower panel). Taken with our current coimmunoprecipitation and Western analysis, these findings suggest that MED1 association with the SULT2A1 promoter is likely through GATA-6 and its binding to the SULT2A1 promoter.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that MED1 mRNA and protein were expressed in the human adrenal cortex. In addition, MED1 was found to additively increase the effects of GATA-6 on the transcription of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1. Moreover, the ability of MED1 to increase SULT2A1 promoter activity was mediated by GATA-6 via its −190 DNA binding site. These data support the hypothesis that adrenal androgen production can be regulated by GATA-6 and MED1.

MED1 is known to be ubiquitously expressed in many mouse and rat tissues (17,18,19,27,28,29). MED1 expression is also seen in the human brain and uterus as well as breast and lung cancer cells (8,15,19). However, to our knowledge, there is no previous study demonstrating the expression of MED1 in the adrenal gland. In this study, we demonstrated abundant expression MED1 mRNA in H295R adrenal cells and that MED1 protein is expressed in the nuclei of human adrenocortical cells. MED1 was previously shown to participate in the transactivation of both nuclear receptors and transcription factors (6,7,8,9,10,11). MED1 also has a function in the regulation of growth, differentiation and metabolism of the central nervous system through nuclear receptors (19). Therefore, we postulated that adrenal MED1 acts as a transcriptional coactivator that regulates adrenal differentiation.

CYP11A1 and CYP17 are known to play critical roles in cholesterol conversion to DHEA in the adrenal ZR. Both genes are also required for production of cortisol and therefore are present in both the adrenal ZF and ZR (4,30). On the other hand, SULT2A1 is predominantly expressed in the cytoplasm of adrenocortical cells in the ZR, in which it acts to convert DHEA to DHEAS. Herein we demonstrated a role for MED1 in regulating expression of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 in H295R cells. MED1 knockdown decreased expression of these genes, whereas increased expression of MED1 augmented transcription of reporter constructs driven by their promoters. In addition, we demonstrated that knockdown of MED1 in adrenal cells decreased production of DHEA and DHEAS. Together these experiments suggest a role for MED1 in adrenal androgen biosynthesis.

MED1 participates in the transactivation of both nuclear receptors and transcription factors (6,28,29). Crawford et al. (6) previously demonstrated that MED1 interacts with five GATA factors using a mouse model: GATA-1, GATA-2, GATA-3, GATA-4, and GATA-6. GATA-6 and the nuclear hormone receptor SF-1 are highly expressed in the adrenal cortex and have previously been shown to have a role in regulating expression of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 (4,13,14,31,32). In this study, we examined the ability of MED1 to influence SF-1 and GATA-6 regulation of the enzymes needed for DHEAS biosynthesis. Whereas MED1 had no significant effect on SF-1 induction of these genes, we demonstrated that MED1 enhanced the transcriptional activation of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 by GATA-6. Based on these findings, our results also indicate that MED1 interacts with GATA-6 protein to enhance the capacity for adrenal androgen production.

To further detail the mechanisms of MED1 action, we demonstrated that deletion or mutation of the SULT2A1 −190 GATA-binding site resulted in a loss of GATA-6 as well as MED1/GATA-6 transactivation. We previously reported that GATA-6 transactivation of SULT2A1 was due to its direct interaction with the −190 GATA-binding site (4). On the other hand, MED1 is known not to have a direct DNA binding domain (6). However, our current coimmunoprecipitation and Western analysis showed that GATA-6 and MED1 interact with each other. These findings along with the results of our ChIP assay suggest that MED1 does not directly bind to the SULT2A1 promoter; rather, it enhances GATA-6 mediated transcription. Human GATA-6 consists of two isoforms transcribed using two distinct promoters (22). The long isoform of GATA-6 (MALT) encodes a protein of 595 amino acids, whereas the short isoform (MYQ) encodes a protein of 449 amino acids. We previously reported that in normal human adrenal gland, the long form was preferentially expressed, whereas in the H295R cells, the short isoform was the major isoform present (4). These observations agree with the results of our current coimmunoprecipitation showing the difference of intensity between the bands of short and long forms. However, both our previous and current studies suggest that there was no significant difference in the effects of either isoform on SULT2A1 transcription. MED1 interactions with the two GATA-6 isoforms have not been previously studied. Herein we demonstrate that the transcriptional activation of SULT2A1 by both isoforms is enhanced by MED1.

Compared with transcription factors, the potential roles for transcription factor coactivators in adrenal androgen production have not been well studied (4,5). In the current study, we demonstrated that the stimulatory effect of GATA-6 on SULT2A1 reporter gene activity was additive with MED1. These results indicate that the expression of SULT2A1 is controlled by not only transcription factors but also their coactivators. Our findings suggest that further studies are needed to define the role of other candidate coactivators in the expression of SULT2A1 and other genes involved in adrenal androgen biosynthesis.

In summary, we confirmed the expression of MED1 mRNA and protein in the adrenal gland and demonstrated that MED1 additively enhanced GATA-6 activation of CYP11A1, CYP17, and SULT2A1 promoter constructs. Down-regulation of MED1 also decreased DHEAS biosynthesis. These data support the hypothesis that adrenal DHEAS production can be regulated by GATA-6 and MED1.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants DK69950, DK43140, and HD11149 from the National Institutes of Health (to W.E.R.).

Disclosure Summary: W.E.R. was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Other authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online June 4, 2009

Abbreviations: ChIP, Chromatin immunoprecipitation; CYP11A1, cholesterol side-chain cleavage; CYP17, 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase; CYP21, 21-hydroxylase; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHEAS, DHEA sulfate; HSD3B2, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2; MED1, mediator complex subunit 1; qPCR, quantitative real-time RT-PCR; RNAi, RNA interference; SF-1, steroidogenic factor 1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein; SULT2A1, steroid sulfotransferase family 2A1; ZF, zona fasciculata; ZR, zona reticularis.

References

- Rainey WE, Carr BR, Sasano H, Suzuki T, Mason JI 2002 Dissecting human adrenal androgen production. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:234–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennerson AR, McDonald DA, Adams JB 1983 Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase localization in human adrenal glands: a light and electron microscopic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 56:786–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Sasano H, Takeyama J, Kaneko C, Freije WA, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2000 Developmental changes in steroidogenic enzymes in human postnatal adrenal cortex: immunohistochemical studies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 53:739–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saner KJ, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Pizzey J, Ho C, Strauss JF, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2005 Steroid sulfotransferase 2A1 gene transcription is regulated by steroidogenic factor 1 and GATA-6 in the human adrenal. Mol Endocrinol 19:184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely J, Amigh KS, Suzuki T, Mayhew B, Sasano H, Giguere V, Laganière J, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2005 Transcriptional regulation of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) by estrogen-related receptor α. Endocrinology 146:3605–3613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford SE, Qi C, Misra P, Stellmach V, Rao MS, Engel JD, Zhu Y, Reddy JK 2002 Defects of the heart, eye, and megakaryocytes in peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-binding protein (PBP) null embryos implicate GATA family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem 277:3585–3592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qi C, Jain S, Rao MS, Reddy JK 1997 Isolation and characterization of PBP, a protein that interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. J Biol Chem 272:25500–25506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qi C, Jain S, Le Beau MM, Espinosa 3rd R, Atkins GB, Lazar MA, Yeldandi AV, Rao MS, Reddy JK 1999 Amplification and overexpression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding protein (PBP/MED1) gene in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:10848–10853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan CX, Ito M, Fondell JD, Fu ZY, Roeder RG 1998 The TRAP220 component of a thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein (TRAP) coactivator complex interacts directly with nuclear receptors in a ligand-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7939–7944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachez C, Lemon BD, Suldan Z, Bromleigh V, Gamble M, Näär AM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman LP 1999 Ligand-dependent transcription activation by nuclear receptors requires the DRIP complex. Nature 398:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näär AM, Beaurang PA, Zhou S, Abraham S, Solomon W, Tjian R 1999 Composite co-activator ARC mediates chromatin-directed transcriptional activation. Nature 398:828–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiveri S, Liu J, Westerholm-Ormio M, Narita N, Wilson DB, Voutilainen R, Heikinheimo M 2002 Differential expression of GATA-4 and GATA-6 in fetal and adult mouse and human adrenal tissue. Endocrinology 143:3136–3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez P, Saner K, Mayhew B, Rainey WE 2003 GATA-6 is expressed in the human adrenal and regulates transcription of genes required for adrenal androgen biosynthesis. Endocrinology 144:4285–4288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiveri S, Liu J, Heikkilä P, Arola J, Lehtonen E, Voutilainen R, Heikinheimo M 2004 Transcription factors GATA-4 and GATA-6 in human adrenocortical tumors. Endocr Res 30:919–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty SM, Mazhawidza W, Bohn AR, Robinson KA, Mattingly KA, Blankenship KA, Huff MO, McGregor WG, Klinge CM 2006 Gender difference in the activity but not expression of estrogen receptors α and β in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Endocr Relat Cancer 13:113–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urahama N, Ito M, Sada A, Yakushijin K, Yamamoto K, Okamura A, Minagawa K, Hato A, Chihara K, Roeder RG, Matsui T 2005 The role of transcriptional coactivator TRAP220 in myelomonocytic differentiation. Genes Cells 10:1127–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Yu S, Jia Y, Ahmed MR, Viswakarma N, Sarkar J, Kashireddy PV, Rao MS, Karpus W, Gonzalez FJ, Reddy JK 2007 Critical role for transcription coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-binding protein/TRAP220 in liver regeneration and PPARα ligand-induced liver tumor development. J Biol Chem 282:17053–17060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Sarkar J, Ahmed MR, Viswakarma N, Jia Y, Yu S, Sambasiva Rao M, Reddy JK 2006 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-binding protein (PBP) but not PPAR-interacting protein (PRIP) is required for nuclear translocation of constitutive androstane receptor in mouse liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 347:485–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Wang XF, Xi ZQ, Gong Y, Liu FY, Sun JJ, Wu Y, Luan GM, Wang YP, Li YL, Zhang JG, Lu Y, Li HW 2006 Decreased expression of thyroid receptor-associated protein 220 in temporal lobe tissue of patients with refractory epilepsy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348:1389–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey WE, Bird IM, Mason JI 1994 The NCI-H295 cell line: a pluripotent model for human adrenocortical studies. Mol Cell Endocrinol 100:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Aoki S, Xing Y, Sasano H, Rainey WE 2007 Metastin stimulates aldosterone synthesis in human adrenal cells. Reprod Sci 14:836–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer A, Gove C, Davies A, McNulty C, Barrow D, Koutsourakis M, Farzaneh F, Pizzey J, Bomford A, Patient R 1999 The human and mouse GATA-6 genes utilize two promoters and two initiation codons. J Biol Chem 274:38004–38016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Gang HX, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Rainey WE 2009 Adrenal changes associated with adrenarche. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 10:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey WE, Viard I, Mason JI, Cochet C, Chambaz EM, Saez JM 1988 Effects of transforming growth factor β on ovine adrenocortical cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 60:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer A, Nemer G, Gove C, Rawlins F, Nemer M, Patient R, Pizzey J 2002 Widespread expression of an extended peptide sequence of GATA-6 during murine embryogenesis and non-equivalence of RNA and protein expression domains. Mech Dev 119(Suppl 1):S121–S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD 2000 The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem 275:38949–38952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JR, Nelson VL, Ho C, Jansen E, Wang CY, Urbanek M, McAllister JM, Mosselman S, Strauss 3rd JF 2003 The molecular phenotype of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) theca cells and new candidate PCOS genes defined by microarray analysis. J Biol Chem 278:26380–26390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C, Zhu Y, Reddy JK 2000 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, coactivators, and downstream targets. Cell Biochem Biophys 32:187–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG 2000 The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev 14:121–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey WE, Nakamura Y 2008 Regulation of the adrenal androgen biosynthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 108:281–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Ikeda Y, Mukai T, Morohashi K, Kurihara I, Ando T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi S, Murai M, Saito I, Saruta T 2001 Expression profiles of COUP-TF, DAX-1, and SF-1 in the human adrenal gland and adrenocortical tumors: possible implications in steroidogenesis. Mol Genet Metab 74:206–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley NA, Rainey WE, Wilson DI, Ball SG, Parker KL 2001 Expression profiles of SF-1, DAX1, and CYP17 in the human fetal adrenal gland: potential interactions in gene regulation. Mol Endocrinol 15:57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]