Abstract

Nitrosyl derivatives of diiron dithiolato carbonyls have been prepared starting from the versatile precursor Fe2(S2CnH2n)(dppv)(CO)4 (dppv = cis-1,2-bis(diphenylphosphinoethylene). These studies expand the range of substituted diiron(I) dithiolato carbonyl complexes. From [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4 ([1(CO)3]BF4), the following compounds were prepared: [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4, [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4, NEt4[1(CO)(CN)2], and 1(CO)(CN)(PMe3). Some if not all of these substitution reactions occur via the addition of two equiv of the nucleophile followed by dissociation of one nucleophile and decarbonylation. Such a double adduct was characterized crystallographically in the case of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)(PMe3)2]BF4. This result shows that the addition of two ligands causes scission of the Fe-Fe bond and one Fe-S bond. When cyanide is the nucleophile, nitrosyl migrates away from the Fe(dppv) site, yielding a Fe(CN)(NO)(CO) derivative. Compounds [1(CO)3]BF4, [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4, and [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 were also prepared by the addition of NO+ to the di-, tri- and tetrasubstituted precursors. In these cases, the NO+ appears to form an initial 36e-adduct containing terminal Fe-NO, followed by decarbonylation. Several complexes were prepared by the addition of NO to the mixed-valence Fe(I)Fe(II) derivatives. The diiron nitrosyl complexes reduce at mild potentials and in certain cases form weak adducts with CO.

Introduction

The substitution chemistry for compounds of the type [Fe2(SR)2(CO)6-xLx]z is well developed for L = tertiary phosphines and cyanide.1 These synthetic transformations were mainly developed en route to functional and structural mimics of the active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase enzymes. The enzymes catalyze the redox interconversion of protons and H2, and do so at near-thermodynamic potentials.2 The high efficiency of the Fe-based catalysts has motivated numerous studies on the synthesis and reactivity of diiron dithiolato carbonyls.

Recently, we reported a series of diiron dithiolate-PMe3 complexes containing nitrosyl ligands. These compounds are of interest because they adopt ‘rotated’ structures as seen in related mixed-valence FeIFeII complexes, the so-called Hox models.3 Associated with their distinctive structure, these nitrosyl compounds are Lewis acidic, which is unknown for other [FeI]2 species, but characteristic of the mixed valence Hox state and its models. Our results indicated the likely stability of other nitrosyl complexes. We therefore have investigated the nitrosyl derivatives of the diiron(I) dithiolates supported by cis-1,2-bis(diphenylphosphinoethylene) (dppv). For studying the fundamental reactivity diiron(I) dithiolates, we have shown that Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)4(dppv) (n = 2, 3) are useful reagents because of their high reactivity and the simplified structures of the products.4 We expected, incorrectly as we show, that NO+ would yield highly polar derivatives of Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)4(dppv).

Nitrosyl derivatives of iron thiolates are of course well known. The first synthetic iron-sulfide cluster, Roussin's Red anion, [Fe2S2(NO)4]2-, led to the corresponding “esters,” Fe2(SR)2(NO)4 (R = alkyl, aryl).5 The Roussin esters have come under renewed scrutiny because of their connection to the so-called dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNIC's).6 Nitric oxide inhibits [NiFe] hydrogenases,7 although the reactivity of NO with [FeFe] hydrogenases have not been reported.

Both NO and NO+ are electrophiles,8 hence it is worth mentioning the reactivity of other electrophiles with Fe2(SR)2(CO)6-xLx. Substituted diiron(I) dithiolates protonate readily.9 Sources of SMe+,10 Br+, I+,11 and HgCl+,12 have long been known to add across the Fe-Fe bond.

Results

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+, a Versatile Synthetic Intermediate

The salts [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(NO)(CO)3(dppv)]BF4 (n = 2, [1(CO)3]BF4; n = 3, [2(CO)3]BF4) were found to form efficiently upon treatment of CH2Cl2 solutions of Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)4(dppv) with NOBF4 at 20 °C (Scheme 1). Indicative of their high electrophilicity, both [1(CO)3]BF4 and [2(CO)3]BF4 exhibit limited stability in MeCN solution at room temperature, although CH2Cl2 and THF solutions are stable for hours. These mononitrosyl complexes were unreactive toward additional equivs of NOBF4 at room temperature.

Scheme 1.

Diiron Dithiolato Nitrosyl Complexes Described in this Work.

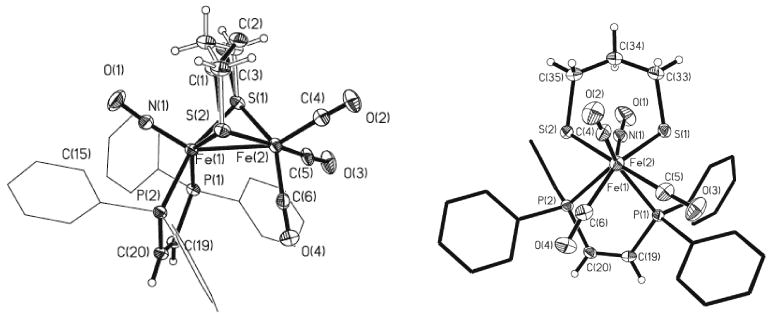

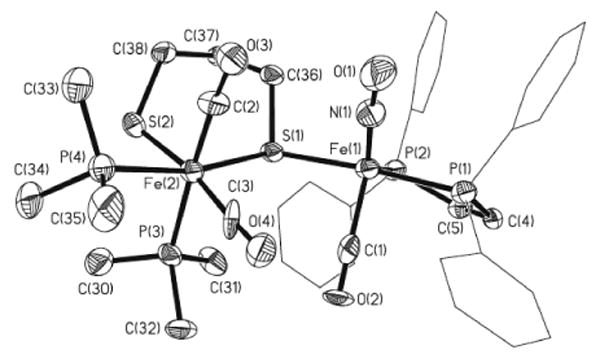

The crystallographically determined structure of [2(CO)3]BF4 revealed that the nitrosyl ligand is apical, the cation having idealized Cs symmetry (Figure 1). The complex exhibits a slight twisting distortion in both the Fe(dppv)(NO)+ and Fe(CO)3 subunits, reminiscent of the structure seen for [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)2(NO)]+.13

Figure 1.

Side-on (left) and end-on (right) views of [2(CO)3]BF4. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 35% probability and are omitted on the phenyl rings for clarity, as are the anion (one phenyl group is perpendicular to the plane of the page). Selected bond distances (Å): Fe(1)–Fe(2), 2.5931(7); Fe(1)-P(1), 2.2791(10); Fe(1)-P(2), 2.3128(10); Fe(1)-N(1), 1.659(2); Fe(2)-C(4), 1.806(3); Fe(2)-C(5), 1.806(3); Fe(2)-C(6), 1.785(3).

In addition to the νNO band at 1796 cm-1, the IR spectrum of [1(CO)3]BF4 features two νCO bands for the Fe(CO)3 subunit. Relative to Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv), these bands are shifted to higher energy by about 50 cm-1. A similar trend is observed for the propanedithiolato complexes.

The 31P NMR spectrum of [1(CO)3]BF4 shows two singlets in a 1:2 ratio, consistent with two isomers that differ with respect to the position of the dppv chelate.4 The smaller signal is assigned to a highly fluxional apical-basal isomer; this signal was found to broaden upon cooling the sample to -80 °C. A singlet assigned to the major isomer proved temperature-invariant, consistent with the dibasal stereochemistry. A similar trend is seen for [2(CO)3]BF4, except that the equilibrium concentration of the apical-basal isomer is barely detectable (Scheme 2, Table 1). The related Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) exhibits similar dynamics, although the apical-basal isomer is far more stabilized (20:1). In the -80 °C 31P NMR spectrum of [2(CO)3]+, four isomers are observed indicative of slowed folding of the propanedithiolate.

Scheme 2.

Isomerization Processes for the Fe(dppv)(NO)+ Subunit.

Table 1.

Ratios of Apical-Basal/Dibasal Isomers (dppv location) for [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)4-x(dppv)(NO)x]x+.

| (S2C2H4)(CO)4 | (S2C2H4)(CO)3(NO) | (S2C3H6)(CO)4 | (S2C3H6)(CO)3(NO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20:1 | 1:2 | 7:1 | 1:>25 (est.) |

Substitution of [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4 by PMe3

The salt [1(CO)3]BF4 proved highly reactive toward nucleophiles. Thus, treatment of [1(CO)3]BF4 with 1 equiv of PMe3 at room temperature gave [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4. The 31P NMR spectrum of [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 displayed singlets in both the dppv and PMe3 regionsm, which implicate axial PMe3 and dibasal dppv. The dibasal disposition of the dppv ligand is further evidenced by the 31P NMR chemical shift (δ74.1), following a pattern seen for related complexes.4

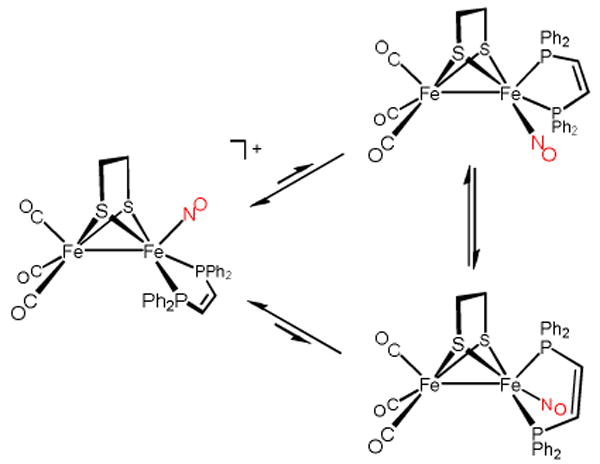

In a test of its relative electrophilicity, equimolar amounts of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) and [1(CO)3]BF4 were treated with one equiv of PMe3 at 20 °C. IR and 31P NMR measurements revealed exclusive consumption of [1(CO)3]BF4. In an attempt to elucidate some details of the substitution mechanism, a solution of [1(CO)3]BF4 was treated with one equiv of PMe3 at -20 °C; we observed complete disappearance of free PMe3, partial consumption of [1(CO)3]+, and the appearance of an intermediate species (νNO = 1727 cm-1). This reaction appears to rapidly give the double adduct [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]+, followed by a slower dissociation of PMe3 that reacts with remaining starting materials (eqs 1-2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

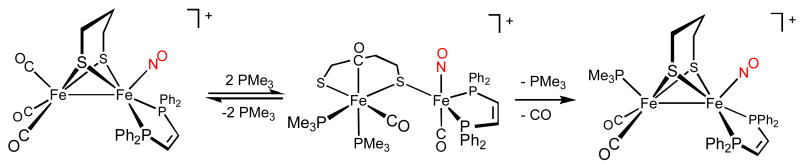

Upon warming to room temperature, the mixture of [1(CO)3]+ and the intermediate converted with good efficiency to [1(CO)2(PMe3)]+. When a solution of [1(CO)3]+ was treated with excess PMe3 at -20 °C, ESI-MS analysis of the reaction mixture confirmed the presence of a species corresponding to [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]+. The related reaction of [2(CO)3]+ with PMe3 gave similar results. The 31P NMR spectrum of the intermediate in the PMe3 region (∼δ25) revealed one major and two minor isomers, in each of which the PMe3 groups are nonequivalent, as virtually required since only low symmetry products could be produced.

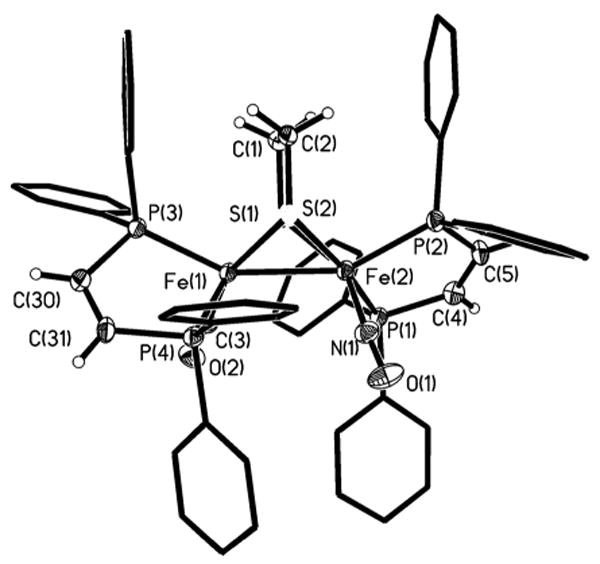

Solutions of [2(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4 readily produced crystals suitable for analysis by X-ray diffraction. The structure of [2(CO)3(PMe3)2]+ features both octahedral and trigonal bipyramidal iron centers, which are assigned as Fe(II) and Fe(0), respectively. The octahedral site features cis thiolates, cis phosphines, and cis carbonyl ligands. Viewing the pentacoordinate site as a trigonal bipyramid, the axial sites are occupied by the acceptor ligands, CO and NO+ (Figure 2). The crystallographic result shows that two molecules of PMe3 added to the Fe(CO)3 site, inducing migration of CO and scission of Fe-Fe and one Fe-S bonds.

Figure 2.

Structure of the cation in [2(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 35% probability and are omitted on the phenyl rings for clarity, as are the anion. Selected bond distances (Å): Fe(1)-N(1), 1.618(9); Fe(1)-C(1), 1.860(11); Fe(1)-P(1), 2.231(3); Fe(1)-P(2), 2.270(3); Fe(1)-S(1), 2.323(3); Fe(2)-S(1), 2.376(2); Fe(2)-S(2), 2.306(3); Fe(2)-C(2), 1.749(11); Fe(2)-C(3), 1.741(11); Fe(2)-P(3), 2.312(3); Fe(2)-P(4), 2.270(3); Fe(1)-Fe(2), 3.969.

Cyano-nitrosyl Complexes

Treatment of [1(CO)3]BF4 with two equiv of Et4NCN gave the dicyanide, Et4N[1(CN)2(CO)]. Shown in Figure 3, variable temperature 31P NMR measurements indicate that Et4N[1(CN)2(CO)] exists exclusively as a single diastereomer in solution wherein the dppv is apical-basal. We propose that this reaction proceeds via relocation of the nitrosyl to the Fe(CN)2 site. The IR spectrum of Et4N[1(CN)2(CO)] resembles that for [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 in the νCO region, but νNO occurs at 41 cm-1 lower energy. The switch of the dppv to apical-basal geometry is also consistent with a Fe(dppv)CO site; in Fe(dppv)NO sites, the dppv is invaribly dibasal in the absence of extreme steric effects.

Figure 3.

202 MHz 31P NMR spectra of Et4N[1(CN)2(CO)] (CD2Cl2 soln) at 20 (top) and -60 °C (bottom).

One equiv of [1(CO)3]BF4 was found to rapidly consume 2 equivs of Et4NCN. This behavior is analogous to the reaction of PMe3 and [1(CO)3]BF4 (see above). When examined by IR spectroscopy at -45 °C, the dicyanation of [1(CO)3]BF4 generated complex mixture characterized by several bands in the νCO and νCN region, although the region 1800 – 1600 cm-1 was blank.13

Despite their high electrophilicity, neither [1(CO)3]BF4 nor [2(CO)3]BF4, were observed to form adducts with CO, even at -80 °C. This behavior contrasts with the monodentate bis(phosphine) nitrosyl complexes, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)2(NO)]BF4 (n = 2, 3), which reversibly bind CO. Thus, it is not surprising that [1(CO)3]BF4 and [2(CO)3]BF4 react with excess PMe3 only near -20 °C, whereas at comparable reactant concentrations, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)2(NO)]BF4 react immediately with PMe3 at -80 °C.

NO as a Trapping Agent for Mixed-Valence Species: [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2(NO)]+ and Related Species

Treatment of [1(CO)3]BF4 with one equiv of dppv slowly and inefficiently afforded the bis(diphosphine), [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4. Alternatively, [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 also arises in the reaction of the dicarbonyl14 Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2 with NOBF4. This route suffered from the tendency of the mononitrosyl to further react with NOBF4 to irreversibly yield, inter alia, Fe(dppv)(NO)2. A potentially versatile route to diiron nitrosyl complexes entails a two-step process that involves one-electron oxidation of diiron(I) precursors followed by treatment with NO. Oxidation of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)214 and trapping with NO gave the corresponding mononitrosyl [Fe2(S2C2H4)(NO)(CO)(dppv)2]BF4 ([1(dppv)(CO)]BF4). The 31P NMR spectrum of [1(dppv)(CO)]BF4 showed four broad singlets at 25 °C, which sharpened upon cooling the sample to -80 °C. We conclude that the two dppv ligands span apical-basal coordination sites, as observed crystallographically in the solid state (Figure 4), but that the dynamic racemization process is subject to a low activation barrier. The precursor complex also exhibits a related dynamic process, but at a higher barrier.14 The complex [1(dppv)(CO)]BF4 is the only diiron ditholate nitrosyl observed in this series that features a basal nitrosyl ligand present in the major observed isomer. 31P NMR studies at low temperatures showed that [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 binds CO reversibly (see supporting info).

Figure 4.

Structure of [1(CO)(dppv)]. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 35% probability and are omitted on the phenyl rings for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å): Fe(1)–Fe(2), 2.5528(13); Fe(2)-P(1), 2.253(2); Fe(2)-P(2), 2.237(2); Fe(2)-N(1), 1.695(6); Fe(1)-C(3), 1.719(7); Fe(1)-P(3), 2.2026(19); Fe(1)-P(4), 2.247(2).

Oxidation of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv) with one equiv FcBF4 followed by the addition of about 1 equiv of NO gave [2(CO)3]BF4. We also prepared [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 via the mixed valence species [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)]BF4.4

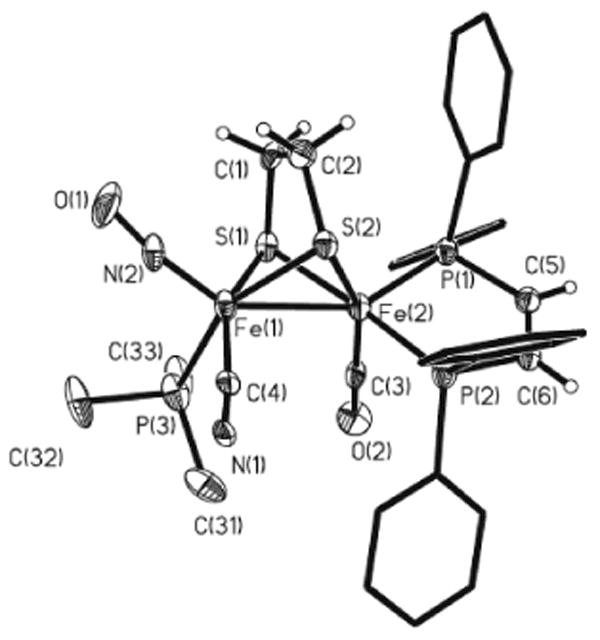

Nitrosyl Migations: Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)(dppv)(PMe3)(NO)

Whereas Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3) is inert towards substitution by cyanide, its nitrosylated derivative [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 was found to react with one equiv of cyanide to produce 1(CN)(CO)(PMe3). The 31P NMR spectrum of 1(CN)(CO)(PMe3) consisted of two doublets in the dppv region, indicative of a single diastereomer. Apparently, rapid turnstile rotation4,14 equilibrates the diastereomeric rotamers. The structure of this species was confirmed crystallographically; the compound is chiral and crystallizes as the racemate (Figure 5). Carbonyl, cyanide, and nitrosyl ligands were distinguished by their bond lengths; the crystallographic refinement also clearly favored one set of assignments. The dppv spans the apical-basal sites, as is typical for Fe(CO)(dppv) centers.4 Cyanide and PMe3 are basal and NO is apical, as is typical in this series of compounds. Distinctively, the nitrosyl is no longer bound to the same Fe as the dppv, a finding that implicates the intramolecular migration of NO (eq 3).

Figure 5.

Structure of 1(CN)(CO)(PMe3). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 35% probability and are omitted on the phenyl rings for clarity. Distances (Å): Fe(1)–Fe(2), 2.275(4); Fe(1)-N(2), 1.631(12); Fe(1)-P(3), 2.275(4); Fe(1)-C(4), 1.926(15); Fe(2)-P(1), 2.183(4); Fe(2)-P(2), 2.208(4); Fe(2)-C(3), 1.713(14).

| (3) |

A similar NO migration reaction had been implicated for the cyanation of [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(PMe3)(NO)]BF4, which gives Fe2(S2C3H6)(CN)(CO)3(PMe3)(NO).13

Electrochemistry of Nitrosyl Derivatives

Cyclic voltammetric studies showed that replacement of CO by NO+ shifts the first reduction and first oxidation events by ca. 1 V anodically, an effect that is akin to that of protonation. Furthermore, the observed redox events are typically reversible: the species, [1(CO)3]+ reduces quasi-reversibly at -630 and -1.090 mV versus Ag/AgCl. The bulky complex [1(CO)(dppv)]+ can be reversibly oxidized and reduced (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Redox Properties for Selected Nitrosyl Complexes. Potentials are Referenced Ag/AgCl. Voltammograms Recorded in CH2Cl2 Solution with 50 mM Et4NPF6, at a 100 mV/s.

| Compound | Oxidation (V) | Reduction (V) |

|---|---|---|

| Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) | -0.060 | -2.070a |

| [1(CO)3]+ | > 1 | -1.150c, -1.610c |

| [2(CO)3]+ | > 1 | -1.210c, -1.730c |

| Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)4 | -0.300b | |

| [1(CO)2(PMe3)]+ | 0.850 | -1.51b, -1.99a |

| Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2 | -0.695b | |

| [1(CO)(dppv)]+ | 0.22b | -1.62b |

Irreversible

Reversible

Reversible at scan rates < 100 mV/s.

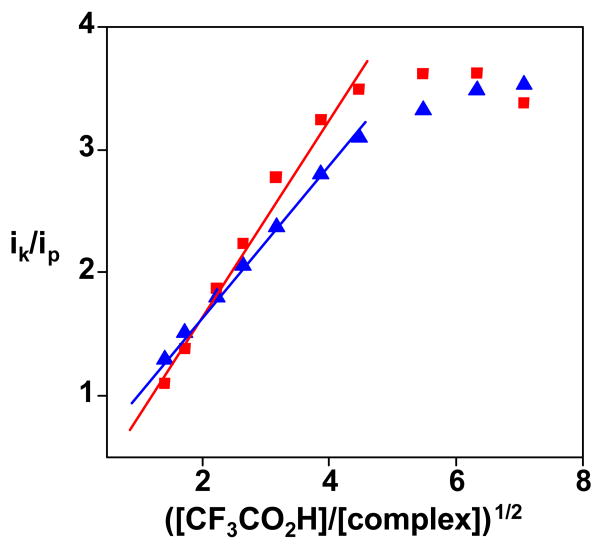

Given their mild reduction potentials, we assayed the redox properties of the diiron nitrosyl complexes in the presence of acids. The simple dppv complexes [1(CO)3]BF4 and [2(CO)3]BF4 exhibited catalytic waves at their primary reductions, both of which were mild (-1.15 and -1.21 V, respectively, versus the Fc0/+ couple see Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Cyclic voltammograms of complex 1 mM [2(CO)3]BF4 in CH2Cl2 (∼50 mM Bu4NPF6) solution as a function of [CF3CO2H] (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 expressed as molar equiv). Scan rate 100 mV s-1 at a glassy carbon electrode 0.3 cm in diam.

At the concentration ratio of [CF3CO2H]/([2(CO)3]+) ≤ 20, no catalysis was observed at the potential of the second reduction step. This behavior is explicable if the acid in the diffusion layer is consumed during the first reduction wave. A rough estimate of the catalytic efficiency of the FeNO derivatives can be obtained from the variation of the catalytic peak current with the acid concentration. As shown in Figure 8, the peak current varies linearly with the square root of the acid concentration, which indicates that the rate determining step in the catalytic reaction is first order in acid (see supplementary material).15 We estimated (see experimental) an overall catalytic rate constant k′ ∼ 130 and 100 M-1 s-1 for [1(CO)3]+ and [2(CO)3]+, respectively. These values compare well with those calculated by the same procedure for cobaloxime catalysts, which are known to be highly efficient.16 Note however that the overall rate constant k′ does not reflect precisely the rate determining step but is a composite of equilibrium and rate constants.

Figure 8.

Plots of the catalytic current as a function of the acid concentration for [1(CO)3]+ (squares) and [2(CO)3]+ (triangles): ik and ip are the peak current in the presence and in the absence of acid, respectively.

At high [H+], the catalytic current becomes almost independent of the acid concentration, indicative of a change in the rate determining step, which could be the release of H2, as has been proposed previously.16 Catalysis by [1(CO)3]+ and [2(CO)3]+ is unaffected by the presence of CO, although the corresponding hexacarbonyl catalysts are poisoned by CO.17

Compounds [1(CO)3]+ and [2(CO)3]+ are not protonated even in the presence of excess triflic acid, consistent with proton reduction catalysis that is initiated by electron-transfer (E step) followed by protonation (C step). The sequence of the two subsequent steps, EC or CE, is unknown. Consistent with the EC mechanism, [2(CO)3]BF4 was chemically reduced with ∼1.1 equiv of Cp2Co at -78 °C to generate the thermally unstable species 2(CO)3. Following the addition of CF3CO2H, we observed regeneration of [2(CO)3]BF4.

Discussion

Nitrosylation provides an easy means to significantly modify the electronic environment of the diiron dithiolato carbonyls without altering its formal oxidation state. Replacement of CO by NO+ causes νCO to increase by 50 cm-1 (Table 1). Such shifts in νCO are about half the effect induced of protonation of related diiron complexes.18 The nitrosyl derivatives exhibit enhanced tendency to undergo substitution reactions as well as to serve as proton reduction catalysts at potentials approaching the thermodynamic limit.19

As shown in this and the previous report, NO+ induces novel stereochemistry on the diiron site. In contrast to all other ligands evaluated on diiron(I) dithiolates, NO+ displays a high preference for the apical site. The complexes characterized in this work all exhibit apical NO+ ligands, except for the (dppv)2 derivatives where steric factors destabilize the isomer containing with both dibasal and apical-basal diphosphines. Even this complex is less stereochemically rigid than the analogous carbonyl derivative.

The structure and reactivity of the complexes [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PR3)2(NO)]+ strongly depends on whether the two phosphines are dppv or PMe3. The complex [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)2(NO)]+ adopts a strongly distorted “rotated” structure,13 whereas [1(CO)3]+ adopts the normal distorted-C2v motif. We suggest that the electronic asymmetry of the (PMe3)2 derivatives, which feature Fe(CO)2(PMe3) and Fe(NO)(CO)(PMe3)+ sites, is greater than for the dppv derivatives described in this work.

The new nitrosyl diiron(I) complexes were prepared by three methods:

Direct electrophilic nitrosylation by attack of NO+. This method is effective but limited by the range of substituted diiron dithiolates, since the diiron center must contain some donor ligands; the hexacarbonyls do not form isolable derivatives upon reaction with NOBF4. We propose that the electrophilic nitrosylation proceeds similarly to the protonation of diiron complexes, i.e. by attack of the electrophile at a terminal metal site.9 We have shown that related 36e diiron nitrosyl complexes are prone to decarbonylation.13

Nitrosylation by attack of NO on mixed valence diiron complexes. This method is complementary to the previous one. It has been shown that NO+ reacts with some metal carbonyls via inner sphere electron-transfer followed by dissociation of NO.20 Many of the oxidized diiron carbonyl dithiolates studied by us previously react with NO.

Substitution of diiron nitrosyl complexes. The considerable electrophilicity of [1(CO)3]BF4 is indicated both by the rate and the stoichiometry of its substitution reactions. The presence of the nitrosyl allows the preparation of highly substituted diiron(I) complexes, which would be difficult to prepare without NO+. These include Et4N[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)2(CO)(dppv)(NO)], [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(dppv)(PMe3)2(NO)]+, and the chiral-at-metal derivative Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(PMe3)(CO)(dppv)(NO). The facility of the intermetallic migration of NO+ limits the range of isolable substituted products. Also impressive is the rate of substitutions: cyanation of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)6 at 25 °C and [2(CO)3]BF4 at −78 °C were found to proceed at comparable rates. This temperature difference roughly corresponds to a 30% decrease in activation energy.

One striking finding is the tendency of [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+ to undergo substitution via the intermediacy of a 2:1 adduct, as illustrated by [(PMe3)2(CO)2Fe(S2CnH2n)Fe(CO)(dppv)(NO)]+ (Scheme 3). These adducts form via the scission of the Fe-Fe bond and one Fe-S bond. The 2:1 adducts illustrate the possibility that other [Fe(I)]2 species substitute via mixed valence adducts. Such a mechanism may be relevant to the finding that attempted monocyanation of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)6 mainly affords the dicyanide.21 The presence of the NO ligand, a very strong acceptor, favors such electron-transfer processes. Related Fe-S scission reactions occur upon the reduction of diiron dithiolates.17,22

Scheme 3.

Pathway Proposed for Substitution of [2(CO)3]+ by PMe3.

Experimental Section

Methods have been recently described.23 NOBF4 was purified by rapid sublimation at 220 °C at ∼ 0.01 mm Hg and was stored in a dry glove box at -30 °C. Since NOBF4 is poorly soluble, the solid was ground to a fine powder prior to use in sensitive reactions.

Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry experiments were conducted in a ∼10-mL one-compartment glass cell, with a Pt wire (counter electrode) and a glassy carbon working electrode. All voltammagrams were referenced vs. an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (50 mM KCl).

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4, [1(CO)3]BF4

A slurry of 0.141 g (1.21 mmol) of pulverized NOBF4 in 20 mL CH2Cl2 was treated with a solution of 0.865 g (1.21 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) in 100 mL of CH2Cl2. The reaction mixture was immediately cooled to 0 °C and after 10 h, the deep red reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. Addition of 50 mL of hexanes to the concentrated solution precipitated the dark red colored product. Yield: 0.912 g (94%). 500 MHz 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 8.6 – 7.2 (m, 20H, C6H5), 3.0 (dd, 2H, PCH), 2.05 (m, 1H, SCH), 1.6 (m, 1H, SCH), 1.3 (m, 1H, SCH), 0.8 (m, 1H, SCH). 202 MHz 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 77.1 (s, dppv), 72.0 (s, dppv). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, -80 °C): δ 78.5 (s, dppv), 73.3 (s, dppv). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2070, 2006; νNO = 1796 cm-1. ESI-MS: m/z = 714.1 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+). Anal. Calcd (Found) for C31H26BF4Fe2NO4P2S2: C, 46.86 (46.86); H, 3.25 (3.27); N, 1.60 (1.75).

[Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4, [2(CO)3]BF4

This compound was prepared following the method described for [1(CO)3]BF4. Yield: 2.0 g (88%). 500 MHz 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 8.5 – 8.2 (m, 20H, C6H5), 2.9 (bs, 2H, PCH), 2.6 (m, 4H, (SCH2)2CH2), 2.0 (m, 2H, (SCH2)2CH2). 202 MHz 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 69.7 (s, dppv). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, -80 °C): δ 76.7 (s, dppv), 75.1 (s, dppv), 72.4 (s, dppv), 69.5 (s, dppv). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2069, 2005; νNO = 1788 cm-1. ESI-MS: m/z = 728.1 ([Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+). Anal. Calcd (Found) for C31H26BF4Fe2NO4P2S2: C, 47.15 (46.56); H, 3.46 (3.41); N, 1.72 (1.86).

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(NO)(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4, [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4

To a mixture of 0.200 g (0.263 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)4 and 0.030 g (0.263 mmol) of finely pulverized NOBF4 was added 15 mL of CH2Cl2. After stirring for 5 min., the solution was concentrated to 5 mL, and the dark red product was precipitated upon addition of 30 mL of hexanes. Crystals were grown via slow diffusion of hexanes into a CH2Cl2 solution of the complex. Yield: 0.19 g (86%). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 74.1 (s, dppv), 25.0 (s, PMe3). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, -70 °C): δ 78.1 (s, dppv), 75.7 (s, dppv), 26.8 (s, PMe3), 23.0 (s, PMe3). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2002, 1958, νNO = 1775. In situ spectra (ReactIR™ 4000, Mettler-Toledo) indicated the presence of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)(NO)]BF4 after 3 h of vigorous stirring at -78 °C: (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2037, 1992, 1957 νNO = 1775. ESI-MS: m/z = 762.2 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(dppv)(PMe3)(NO)]+). Anal. Calcd (Found) for C33H35BF4Fe2NO3P3S2: C, 46.67 (46.66); H, 4.15 (4.37); N, 1.65 (1.62).

Synthesis via Oxidation and Trapping with NO

To a solution of 0.196 g (0.258 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)4 in 15 mL of CH2Cl2, cooled to -45 °C, was added 0.070 g (0.256 mmol) of FcBF4. The IR spectrum of the purple solution displayed signals matching [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)]BF4.4 The reaction vessel was sealed and to the cooled solution was injected 6 mL (0.268 mmol) of NO gas. After 1 h, the IR spectrum of the resulting deep red solution matched that for [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4. The product precipitated upon addition of 60 mL of hexanes. Yield: 0.116 g (53%). Analogous procedures were followed for the sequential oxidation and trapping of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv) to give [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4: To a solution of 0.045 g (0.062 mmol) of Fe2S2C3H6 in 5 mL of CH2Cl2, cooled to -45 °C, was added a solution of 0.017 g (0.062 mmol) of FcBF4 in 5 mL of CH2Cl2. To the resultant reaction mixture was added 3.2 mL of NO (0.124 mmol), and the reaction vessel was sealed. After 20 min, the IR spectrum matched that of [2(CO)3]BF4, and the product was precipitated upon addition of 50 mL of hexanes. Yield: 77%.

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(dppv)2(NO)]BF4, [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4

To a solution of 0.150 g (0.142 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2 in 20 mL of CH2Cl2, cooled to -45 °C, was added 0.039 g (0.142 mmol) of FcBF4. An immediate IR spectrum of the dark brown solution displayed signals attributed to [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(μ-CO)(dppv)2]BF4: νCO = 1959 (s), 1887 (w, br) cm-1.23 The reaction vessel was sealed and to the cooled solution was injected 3.6 mL (0.161 mmol) of NO gas. After 1 h, the resultant dark brown solution displayed an IR spectrum corresponding to [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4. The solution was warmed to room temperature and concentrated in vacuo to ∼ 5 mL. The product precipitated upon addition of 30 mL of Et2O. Impurities observed in the 31P NMR spectrum can be removed after several recrystallizations from CH2Cl2-Et2O. Yield: 0.080 g (49%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 8.2 – 6.8 (m, 40H, dppv), 1.7 – 0.8 (m, 4 H, SCH2CH2S). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 101.7 (br s, dppv), 87.8 (broad s, dppv), 81.2 (br s, dppv), 74.9 (br s, dppv). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1928, νNO = 1760 cm-1. ESI-MS: m/z = 1054.2 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(dppv)2(NO)]+). Acceptable CHN analyses were not be obtainable. Anal. Calcd (Found) for C55H48BF4Fe2NO2P4S2: C, 57.87 (56.00); H, 4.24 (4.00); N, 1.23 (1.31). Excess of NOBF4 gave Fe(dppv)(NO)2:24 νNO = 1718 and 1666 cm-1; ESI-MS: m/z = 512.

Alternative routes were examined: addition of dppv to 1(CO)3, and treatment of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2 with NOBF4. The raw product contained the targeted complex as well as unidentified impurities as indicated by the 31P NMR and IR spectra. Treatment of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)2(dppv)2(NO)]BF4 with NOBF4 produced Fe(NO)2(dppv).24

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)2(NO)]BF4, [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4

Onto a frozen solution of 0.206 g (0.26 mmol) of [1(CO)3]BF4 in 10 mL of CH2Cl2 was distilled 1 mL of PMe3. The mixture was allowed to thaw at -78 °C, warmed in an ice water bath for 1 min, followed by cooling again to -78 °C. The IR spectrum of the reaction mixture indicated [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4. Addition of 50 mL of hexanes to the reaction mixture yielded a dark brown oil that was dried in vacuo. IR spectra of the redissolved material contained showed traces of [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4, indicative of the thermal instability of [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4. 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 0 °C), A, B, and C correspond to three isomers: δ 98.4 (d, JP-P = 48.3, dppv A), 98.0 (d, JP-P = 44.3, dppv B), 97.3 (d, JP-P = 39.7, dppv C), 81.5 (d, JP-P = 48.9, dppv A), 81.3 (d, JP-P = 45.8, dppv B), 78.8 (d, JP-P = 38.4, dppv C), 25.3, 17.8 (d, J = 64.1, PMe3 C), 17.0 (d, J = 62.5, PMe3 A), 10.0 (ABq, J = 292, JAB = 245, PMe3 B), 6.4 (d, J = 64.2, PMe3 C), 5.4 (d, J = 65.6, PMe3 A).

Crystallization of [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(dppv)(PMe3)2(NO)]BF4, [2(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4

Approximately 0.2 mL of PMe3 was distilled onto a frozen solution of 0.070 g of [1(CO)3]BF4 in 7 mL of CH2Cl2. Aliquots briefly warmed (<2 min.) to room temperature displayed an IR spectrum that indicated the presence of [2(CO)3(PMe3)2(NO)]BF4. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2021, 1971, 1951. νNO = 1721 cm-1. NMR (CD2Cl2, -20 °C): A, B, and C correspond to three isomers: δ 97.4 (d, JP-P = 34.2, dppv A), 95.0 (d, JP-P = 28.6, dppv B), 78.2 (d, JP-P = 38.2, dppv A), 76.9 (d, JP-P = 29.0, dppv B), 15.9 (d, JP-P = 71.6, PMe3 A), 15.2 (d, JP-P = 72.4, PMe3 C), 9.0 (ABq, J = 964.5, JAB = 193, PMe3 B), 4.1 (d, JP-P, PMe3 A), 2.8 (d, JP-P = 71.9, PMe3 C). The dppv signals for isomer C are not reported because of overlap with isomer A's signals). The reaction mixture was thawed to -45 °C followed by transfer via cannula to a Schlenk tube cooled to -78 °C. This solution was layered with 50 mL of a 1/1 mixture of Et2O and hexane and stored at -30 °C. After 1 week, red rhombs were visible.

Reaction of [1(CO)3] with 1 equiv PMe3

To a J. Young NMR tube was added a solution of 0.025 g (0.03 mmol) of [1(CO)3]BF4 in 1 mL of CD2Cl2. The solution was frozen in liquid nitrogen, and to it was added 0.3 mL of a 0.13 M solution of PMe3 in CH2Cl2. The tube was immediately capped, immersed in liquid nitrogen, and evacuated. The contents were allowed to warm and were monitored by NMR spectroscopy at various temperatures. At -38 °C, no reaction was observed. Upon warming to 0 °C, partial consumption of [1(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4 and nearly complete consumption of PMe3 was accompanied by growth of several peaks. These peaks were assigned to one major (“B”) and two minor (“A” and “C”) intermediates (see above spectra assignments). Upon warming to room temperature overnight, conversion of the remaining intermediate(s) to [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 was observed.

NEt4[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)2(CO)(dppv)(NO)]

A solution of 0.503 g (0.63mmol) of [1(CO)3]BF4 in 30 mL of MeCN was cooled to -45 °C followed by treatment with a solution of 0.199 g (1.3 mmol) of NEt4CN in 30 mL of MeCN, also cooled to -45 °C. The solution immediately darkened, and after 3 h, the dark brown solution was allowed to warm to room temperature followed by stirring overnight. After the solvent was removed in vacuo, the residue was extracted into 5 mL of CH2Cl2 and the product was precipitated by the addition of 30 mL of Et2O. IR (CH2Cl2): νCN = 2100, νCO = 1923, νNO = 1719. 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 96.1 (s, dppv). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, -60 °C): δ 99.3 (d, JP-P = 22.4, dppv), 94.1 (d, JP-P = 22.4, dppv). MS ESI: m/z = 710.0 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)2(CO)(dppv)(NO)]+), 682.0 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)2(dppv)(NO)]+). Suitable CHN analyses were not be obstained.

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)(CN)(dppv)(PMe3)(NO)]BF4, [1(CO)(CN)(PMe3)]BF4

A solution of 0.221 g (0.26 mmol) of [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 in 30 mL of CH2Cl2 was treated with a solution of 0.041 g (0.26 mmol) of NEt4CN in 10 mL MeCN. After 60 min., the dark brown-colored reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was extracted into 30 mL of toluene. The dark red-colored extract was concentrated followed by dilution with 30 mL of hexanes to precipitate the product. Yield: 0.065 g (33%). 1H NMR (d8-toluene): δ 8.5 – 6.7 (m, C6H5 and P2C2H2), 2.1 – 1.6 (m, S2C2H4), 1.26 (d, JP-H = 9.9, 9H, PCH3). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 95.3 (d, JP-P = 20.9, dppv), 74.2 (d, JP-P = 24.5, dppv), 7.9 (s, PMe3). IR (CH2Cl2): νCN = 2096, νCO = 1910, νNO = 1734. FD-MS: m/z = 760 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)(dppv)(PMe3)(NO)]+). Anal. Calcd (Found) for C33H35Fe2N2O2P3S2: C, 52.54 (52.13); H, 4.72 (4.64); N, 3.53 (3.68).

Relative Electrophilicity of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+

To a solution of 0.015 g (0.02 mmol) of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]BF4 and 0.014 g (0.02 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was added 0.5 mL of 0.19 M solution of PMe3 in CH2Cl2. The reaction was monitored by IR spectroscopy over the course of 7 h during which time the absorption bands for [1(CO)3(NO)]BF4 decayed and those for [1(CO)3(PMe3)(NO)]BF4 increased. The bands for Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) remained unchanged.

Semi-quantitation of Catalytic Proton Reduction

An electron transfer followed by a fast catalytic reaction can be formulated by the following equations:

|

where k′ is the rate constant for the reaction of reagent Z with the reduced species R to give product P. When the concentration of Z is large compared to the concentration of the catalyst and the potential sufficiently negative with respect to E1/2, the catalytic current ik is given by the following relation:15

where n is the number of electrons involved in the catalytic process, F the Faraday constant, A the area of the electrode, and D the diffusion coefficient for the catalyst. For graphs of ik against Cz1/2, the slope is nFACO(k′D)1/2. The value for ACOD1/2 can be obtained from the voltammetric peak current, ip, of the catalyst in the absence of acid:

where ν is the potential scan rate.

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals were mounted on a thin glass fiber using Paratone-N oil (Exxon). Data, collected at 198 K on a Siemens CCD diffractometer, were filtered to remove statistical outliers. The integration software (SAINT) was used to test for crystal decay as a bilinear function of X-ray exposure time and sin(Θ). The data were solved using SHELXTL by Direct Methods; atomic positions were deduced from an E map or by an unweighted difference Fourier synthesis. H atom U's were assigned as 1.2Ueq for adjacent C atoms. Non-H atoms were refined anisotropically. Successful convergence of the full-matrix least-squares refinement of F2 was indicated by the maximum shift/error for the final cycle. The assignment of NO vs CO was tested by refining the cations with these ligands interchanged. Optimal refinements were found only for cases with the Fe(dppv)(NO) centers.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammogram of 1 mM [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 in CH2Cl2 solution (50 mM Bu4NPF6, 20 °C, 100 mV/s).

Table 2.

IR Data (cm-1, CH2Cl2 soln) for Selected Compounds.

| Compound | νCO | νNO |

|---|---|---|

| [1(CO)3]+ | 2070, 2006 | 1796 |

| [1(CO)2(PMe3)]+ | 2002, 1958 | 1775 |

| [1(CO)(dppv)]+ | 1928 | 1760 |

| 1(CO)(PMe3)(CN) | 1910 | 1734 |

| [1(CN)2(CO)]- | 1923 | 1719 |

Table 4.

Details of Data Collection and Structure Refinement.

| [2(CO)3]BF4 | [1(CO)2(PMe3)]BF4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| chemical formula | C32H28BF4Fe2NO4P2S2 | C35H39BCl4F4Fe2NO3P3S2 | |

| Formula weight | 815.12 | 1019.01 | |

| T (K) | 193(2) | 193(2) | |

| Space group | P 21/c | P 21/n | |

| a (Å) | 10.094(4) | 15.2650(11) | |

| b (Å) | 17.701(7) | 19.3588(13) | |

| c (Å) | 19.493(8) | 15.5567(11) | |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 | |

| β (deg) | 97.814(6) | 95.573(3) | |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 | |

| Z | 4 | 4 | |

| V (Å3) | 3451(2) | 4575.5(6) | |

| λ (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | |

| Dcalc (g cm-3) | 0.001569 | 0.001479 | |

| μ (cm-1) | 0.01114 | 0.01114 | |

| R(Fo2) | 0.0278 | 0.0406 | |

| Rw(Fo2) | 0.0568 | 0.1086 | |

| [1(CO)(dppv)]BF4 | [1(CN)(CO)(PMe3)]BF4 | [1(CO)3(PMe3)2]BF4 | |

| chemical formula | C58H54BCl6F4Fe2NO2P4S2 | C33H35Fe2N2O2P3S2 | C38H46BF4Fe2NO4P4S2 |

| Formula weight | 1396.23 | 760.36 | 967.27 |

| T | 193(2) | 193(2) | 193(2) |

| Space group | P21 | P na21 | P-1 |

| a (Å) | 10.8808(16) | 19.629(5) | 13.4269(19) |

| b (Å) | 17.757(3) | 11.016(3) | 13.637(2) |

| c (Å) | 16.692(2) | 32.186(9) | 14.435(2) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 | 74.158(9) |

| β (deg) | 104.511(3) | 90 | 73.229(9) |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 | 79.917(9) |

| Z | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| V (Å3) | 3122.3(8) | 6959(3) | 2421.2(6) |

| λ (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Dcalc (g cm-3) | 0.001485 | 0.001451 | 0.001327 |

| μ (cm-1) | 0.00945 | 0.01124 | 0.00868 |

| R(I >2σ)a | 0.0610 | 0.0886 | 0.0773 |

| Rw(I >2σ)b | 0.1256 | 0.1186 | 0.1628 |

R = Σ‖Fo| - |Fc|/Σ|Fo|.

Rw = {[w(|Fo| - |Fc|)2]/Σ [wFo2]}1/2, where w = 1/σ2(Fo).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. We thank Terésa Prussak-Wieckowska for assistance with the crystallographic analyses. M.T.O. thanks the NIH Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Program for a fellowship. We thank the CNRS-UIUC cooperation program for support for F.G. during his time at UIUC.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: X-ray crystallographic data and additional spectroscopic and synthetic details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Liu X, Ibrahim SK, Tard C, Pickett CJ. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:1641–1652. [Google Scholar]; Mejia-Rodriguez R, Chong D, Reibenspies JH, Soriaga MP, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12004–12014. doi: 10.1021/ja039394v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhao X, Georgakaki IP, Miller ML, Yarbrough JC, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9710–9711. doi: 10.1021/ja0167046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4366–4413. doi: 10.1021/cr050191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu T, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7008–9. doi: 10.1021/ja071851a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Justice AK, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6152–6154. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, van der Vlugt JI, Wilson SR. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1655–1664. doi: 10.1021/ic0618706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler AR, Megson IL. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1155–1165. doi: 10.1021/cr000076d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster MW, Cowan JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4093–4100. [Google Scholar]; Stamler JS, S DJ, Loscalzo J. Science. 1992;258:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1281928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Harrop TC, Song D, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3528–9. doi: 10.1021/ja060186n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang HW, Tsou CC, Kuo TS, Liaw WF. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:2196– 2204. doi: 10.1021/ic702000y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasna AI, Rittenberg D. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1954;40:225–227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.40.4.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ahmed A, Lewis RS. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97:1080–1086. doi: 10.1002/bit.21305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter-Addo GB, Legzdins P. Metal Nitrosyls. Oxford University Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezzaher S, Capon JF, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Pichon R, Kervarec N. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:3426–3428. doi: 10.1021/ic0703124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treichel PM, C RA, Matthews R, Bonnin KR, Powell D. J Organomet Chem. 1991;402:233–248. [Google Scholar]; Georgakaki IP, Miller ML, Darensbourg MY. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:2489–2494. doi: 10.1021/ic026005+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines RJ, de Beer JA, Greatrex R. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1976:1749–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arabi MS, Mathieu R, Poilblanc R. Inorg Chim Acta. 1977;23:L17–L18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen MT, Bruschi M, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008 doi: 10.1021/ja802268p. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB. Chem Commun. 2007:2019–21. doi: 10.1039/b700754j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods Fundamentals and Applications. J Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu XL, Brunschwig BS, Peters JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8988–8998. doi: 10.1021/ja067876b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borg SJ, Behrsing T, Best SP, Razavet M, Liu X, Pickett CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16988–16999. doi: 10.1021/ja045281f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X, Hsiao YM, Lai CH, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. Inorg Chem. 2002:699–708. doi: 10.1021/ic010741g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gloaguen F, Lawrence JD, Rauchfuss TB, Bénard M, Rohmer MM. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/ic025838x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felton GAN, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL, Evans DH. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9181–9184. doi: 10.1021/ic060984e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connelly NG, Demidowicz Z, Kelly RL. Dalton Trans. 1975:2335–2340. [Google Scholar]; Ashford PK, Baker PK, Connelly NG, Kelly RL, Woodley VA. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1982:477–479. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gloaguen F, Lawrence JD, Schmidt M, Wilson SR, Rauchfuss TB. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12518–12527. doi: 10.1021/ja016071v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felton GAN, Vannucci AK, Chen J, Lockett LT, Okumura N, Petro BJ, Zakai UI, Evans DH, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12521–12530. doi: 10.1021/ja073886g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Aguirre de Carcer I, DiPasquale A, Rheingold AL, Heinekey DM. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:8000–8002. doi: 10.1021/ic0610381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Justice AK, Nilges M, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR, De Gioia L, Zampella G. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5293–5301. doi: 10.1021/ja7113008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillaume P, Wah HLK, Postel M. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:1828–31. [Google Scholar]