Abstract

Objective

To describe self-reported practice patterns of PCPs for the diagnosis, treatment, and management of men with CP/CPPS.

Methods

556 PCPs in Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles were presented a vignette, which described a man with typical CP/CPPS symptoms, followed by questions about CP/CPPS.

Results

The response rate was 52%. Only 62 percent of respondents reported ever seeing a patient like the one described in the vignette. Fully 16% of respondents were “not at all” familiar with CP/CPPS, and 48% were “not at all” familiar with the NIH classification scheme for prostatitis. PCPs reported practice patterns regarding diagnosis and treatment of CP/CPPS, which are not supported by evidence.

Conclusions

Although studies suggest that CP/CPPS is common, many PCPs reported little or no familiarity, important knowledge deficits, and limited experience in managing men with this syndrome.

Keywords: chronic prostatitis, primary care physicians, survey, practice patterns

INTRODUCTION

The term “prostatitis” is used to describe several conditions, including well-defined acute and chronic bacterial infections, poorly defined chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and asymptomatic inflammation in the prostate identified in pathology specimens. To limit confusion, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed a classification system and definitions for the prostatitis syndromes (1) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Categories of the Prostatitis Syndromes, According to the NIH Classification System(20).

| Category | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| I. Acute bacterial prostatitis | Associated with severe symptoms of prostatitis, systemic infection, and acute bacterial urinary tract infection |

| II. Chronic bacterial prostatitis | Caused by chronic bacterial infection of the prostate with or without symptoms of prostatitis and usually with recurrent urinary tract infections caused by the same bacterial strain |

| III. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome* | Characterized by symptoms of chronic pelvic pain and possibly symptoms on voiding in the absence of urinary tract infection |

| IV. Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis | Characterized by evidence of inflammation of the prostate in the absence of genitourinary tract symptoms; an incidental finding during evaluation for other conditions, such as infertility or elevated serum prostate- specific antigen levels |

This category is subdivided into inflammatory (category IIIA) and noninflammatory (Category B) prostatitis.

Although literature reviews provide compelling evidence that histologic prostatitis is common (2, 3), symptomatic, clinically-evident prostatitis is of greater importance to the patient and physician. The prevalence of current prostatitis-like symptoms (4, 5) or a previous physician’s diagnosis of prostatitis (6) is about 10%.

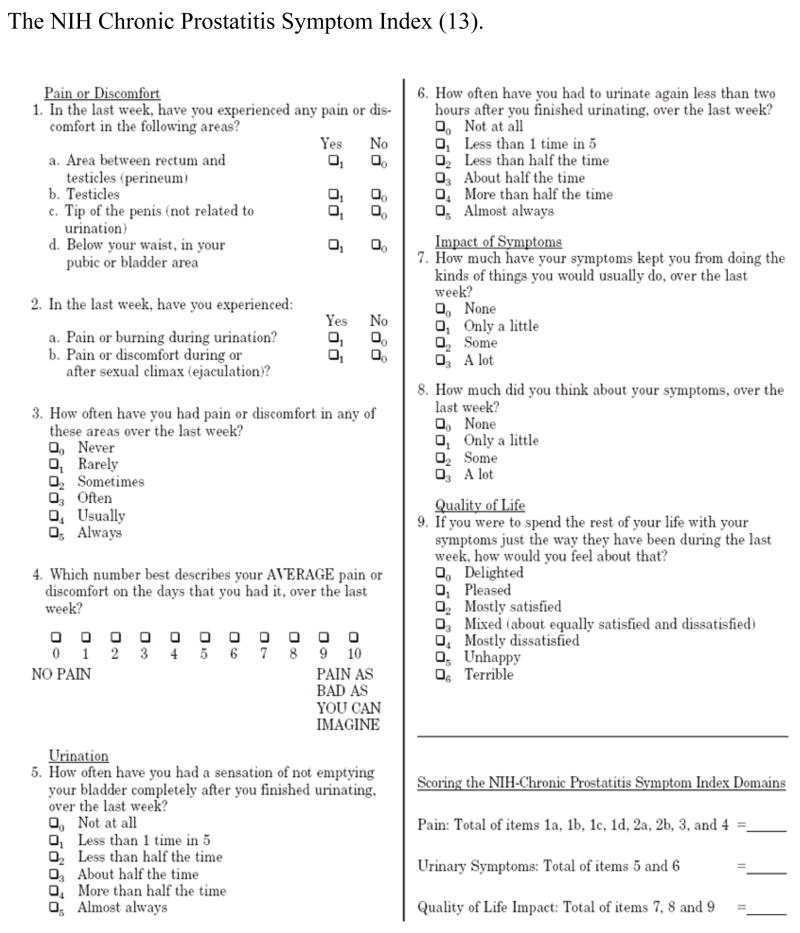

This study focuses on the predominant type of prostatitis, NIH Category III or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). CP/CPPS is a common(7), bothersome condition among men of all ages that impairs health-related quality of life(8, 9) and has a substantial economic impact (10, 11). The hallmark of CP/CPPS is pelvic area pain (12). The NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) (Figure) is a reliable, valid, self-administered index that measures symptoms of chronic prostatitis and their impact on daily life (13).

Figure.

The NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (13).

Although patients with CP/CPPS have traditionally been managed by urologists, many present first to primary care physicians with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS. Nonetheless, few studies (14–16) have examined what is known about primary care physicians’ practice patterns regarding CP/CPPS. To ascertain the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of primary care physicians about the diagnosis and treatment of CP/CPPS, we conducted a multi-center survey of primary care physicians in 2006.

METHODS

Study Sample

There was a convenience sample of 556 practicing primary care physicians who were eligible for the study at the participating institutions (Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), and Access Community Health Network (Access)). Access, located in Chicago, is the largest federally qualified health center organization in the United States. Lists of affiliated primary care physicians were obtained from the participating institutions, and these lists were refined using information provided by the General Medicine Divisions and the hospital directories to exclude physicians without direct patient care, residents and fellows, and those seeing only pediatric patients. A current interoffice mailing address was obtained for each physician.

Study Design

The Institutional Review Board of each institution approved the study and survey. Brief (<15 minutes), self-administered, pre-tested questionnaires were mailed to 556 physicians at the 3 institutions. The mailing included a cover letter from the Principal Investigator, a fact sheet describing the study, a $5 coffee gift card, and a pre-stamped, pre-addressed return envelope. About 2 weeks after the initial mailing, all physicians were mailed a brief 1-page thank you/reminder letter. Nonrespondents were sent a second complete packet about 3 weeks after the initial mailing. No further attempts to contact nonrepondents were made. Voluntary completion and return of the survey implied informed consent.

Questionnaire Development

A literature review identified 3 survey studies of primary care physicians regarding CP/CPPS as a starting point in questionnaire development (14–16). Across the study sites of Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles, we conducted a series of 5 primary care physician focus groups and subsequently drafted a preliminary questionnaire. The draft questionnaire was modified after several cognitive interviews with primary care physicians across the 3 study sites. The modified questionnaire was then pre-tested (with primary care physicians as well as a panel of 5 experts in CP/CPPS from North America) and refined following the debriefing. The finalized questionnaire (Appendix) included 5 domains; familiarity and experience with CP/CPPS, diagnosis (which included referral threshold), treatment, perceptions on managing patients with CP/CPPS (which included knowledge questions), and demographics. A vignette was presented and used to “anchor” responses to questions regarding how the physicians would evaluate and treat such a patient. The vignette read as follows:

A healthy 38-year old man reports several months of nonspecific perineal pain and urinary frequency. He is in a longstanding, monogamous relationship and has no history of STDs or UTIs. His prostate examination is normal. His urinalysis is normal and his urine culture is negative.

For analytic purposes, diagnostic tests and treatment recommendations were stratified into common (at least 50% of respondents do it “more than half the time” or “almost always”) and uncommon (at least 50% obtain a test “rarely” or “never” and recommend treatment to “very few” or “none”).

Statistical Analyses

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study, which utilized questionnaires to obtain pertinent data. The completed questionnaires were keyed into a data entry system, and double blind data entry provided 100% verification of coding and data entry. Analyses involved primarily the generation of descriptive statistics with appropriate confidence intervals. All analyses were performed at the data center (at the University of Illinois, Chicago) and utilized Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 15 (17).

Sample size

As part of the questionnaire development process, a set of correct answers was identified related to basic knowledge about CP/CPPS, and the proportion of primary care physicians who provided correct responses was calculated for each question. A similar study evaluating practice patterns in primary care physicians for the diagnosis and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) indicated that approximately one-third of these physicians followed all of the recommended guidelines (18). Because CP/CPPS is less familiar to PCPs than BPH, we expected that a lower proportion (estimated at 25%) would demonstrate adequate knowledge. Assuming a 25% population prevalence of PCP correct responses and a 95% probability that the proportion obtained would be +/− 5% of the population value, the sample size required was calculated to be approximately 288 subjects.

Descriptives and Predictors of Primary Care Physicians’ Responses

Descriptive statistics were used for all survey responses and physician characteristics. Chi-square and ANOVA were performed to detect variation in having familiarity with the CP/CPPS condition, its symptoms, and etiology based on physician demographic characteristics. Ability to identify symptoms of CP/CPPS and its etiology were considered as knowledge questions and responses were coded as correct and incorrect. Logistic regression analysis was used to predict which characteristics of primary care physicians were associated with the likelihood of performing various tests and recommending various treatments.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Among the 556 primary care physicians who were mailed the questionnaire, a total of 289 (52%) responded, most of those (59%) from the initial mailing. Respondents were distributed approximately equally by gender (53% male), and the time from graduation from medical school was an average of 19 years (range 1–51). Respondent practice type was community-based (38%), hospital-based (40%), and private practice-based (22%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Responding Physicians (n= 289)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Years since graduation from medical school (mean, SD) | 18.9 ± 10.8 |

|

| |

| Percentage of professional time devoted to clinical practice (mean %) | 72.8 % |

|

| |

| Practice setting | |

| Community-based | 37.7 % |

| Hospital-based | 39.9 % |

| Office-based/Private practice | 22.3 % |

|

| |

| Percent of patients that are male (mean, SD) | 37.8 ± 31.9 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 53.1 % |

| Female | 46.9 % |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5.5 % |

| White | 64.9 % |

| Black or African American | 5.9 % |

| Asian | 22.5 % |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.4 % |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.7 % |

Diagnosis of CP/CPPS

Only 62 percent (180/289) of respondents reported ever seeing a patient like the one described in the vignette. Those physicians had seen a mean of 3.2 patients like this (range 0–50) over the past 12 months, and reported a mean of 3.4 patients in their practice with a CP/CPPS diagnosis (0–30). Responders were asked, “When evaluating a patient like the one in the vignette to confirm the diagnosis, or to rule out other causes of his symptoms, how often do you do the following…”; their responses to 9 items are shown in Table 3. We found that testing for Chlamydia and gonorrhea and ordering serum creatinine were common diagnostic tests (reported being used at least more than half the time in 86% and 59%, respectively), and that obtaining pre- and post- massage urine cultures, ordering abdominal/pelvic CT scans, post void residuals, and prostate ultrasounds were all uncommon diagnostic tests (range of 61% to 70%, used rarely or never). Although testing for prostate specific antigen has not been shown to be helpful in the diagnosis of CP/CPPS(19, 20), approximately 50% of respondents reported ordering this test about half the time or more.

Table 3.

Reported Frequency of Primary Care Physicians’ Performing Diagnostic Tests in the Evaluation of a Patient with Symptoms Suggestive of CP/CPPS* (n= 180).

| I refer to a specialist at this point | |

| Almost always | 9.3 % |

| More than half the time | 15.7 % |

| About half the time | 16.3 % |

| Less than half the time | 19.8 % |

| Rarely | 29.7 % |

| Never | 9.3 % |

|

| |

| I obtain testing for Chlamydia and gonorrhea | |

| Almost always | 70.6 % |

| More than half the time | 15.6 % |

| About half the time | 5.0 % |

| Less than half the time | 6.1 % |

| Rarely | 1.7 % |

| Never | 1.1 % |

|

| |

| I order post void residual | |

| Almost always | 4.5 % |

| More than half the time | 6.8 % |

| About half the time | 6.2 % |

| Less than half the time | 17.5 % |

| Rarely | 33.9 % |

| Never | 31.1 % |

|

| |

| I order serum creatinine | |

| Almost always | 39.9 % |

| More than half the time | 19.1 % |

| About half the time | 9.6 % |

| Less than half the time | 8.4 % |

| Rarely | 15.7 % |

| Never | 7.3 % |

|

| |

| I order abdominal/pelvic CT scan | |

| Almost always | 4.0 % |

| More than half the time | 6.2 % |

| About half the time | 9.6 % |

| Less than half the time | 10.7 % |

| Rarely | 47.5 % |

| Never | 22.0 % |

|

| |

| I obtain pre- and post- prostate massage urine cultures | |

| Almost always | 12.4 % |

| More than half the time | 10.7 % |

| About half the time | 7.3 % |

| Less than half the time | 8.5 % |

| Rarely | 27.1 % |

| Never | 33.9 % |

|

| |

| I order serum prostate specific antigen test | |

| Almost always | 21.7 % |

| More than half the time | 18.9 % |

| About half the time | 8.6 % |

| Less than half the time | 9.1 % |

| Rarely | 21.1 % |

| Never | 20.6 % |

|

| |

| I order a prostate ultrasound | |

| Almost always | 2.3 % |

| More than half the time | 5.7 % |

| About half the time | 10.3 % |

| Less than half the time | 14.3 % |

| Rarely | 33.7 % |

| Never | 33.7 % |

|

| |

| Perform any other procedure | |

| Yes | 5 % |

| No | 95 % |

Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

Treatment of CP/CPPS

Physicians were asked, “For how many of your patients like the one described in the vignette have you recommended treatment (either initial treatment or follow-up treatment) with…”; their response to the following 12 items are shown in Table 4. Antibiotics were a common treatment recommendation (72% recommending more than half the time or almost always), while prostate massage, pelvic floor physical therapy, 5- alpha reductase inhibitors, bladder analgesics, complementary/alternative therapies, narcotic pain medications, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and anticholinergics were all uncommon recommendations (range of 75% to 97%, treated very few or none). Despite being a common treatment recommendation, the use of antibiotics for the treatment of men with CP/CPPS is not supported by the evidence (21). Although the evidence for the use of alpha blockers is inconsistent (22), we found that 41% of respondents recommended this treatment about half the time or more. While not supported by evidence, NSAIDs are often considered an adjunctive medication and our results showed that 61% recommended anti-inflammatory medications about half the time or more.

Table 4.

Reported Frequency of Primary Care Physicians’ Treatment Recommendations for a Patient with Symptoms Suggestive of CP/CPPS* (n= 180)

| Antibiotics | |

| Almost all | 36.5 % |

| More than half | 35.4 % |

| About half | 11.2 % |

| Less than half | 7.3 % |

| Very few | 4.5 % |

| None | 5.1 % |

|

| |

| Alpha blockers | |

| Almost all | 2.3 % |

| More than half | 19.4 % |

| About half | 19.4 % |

| Less than half | 13.7 % |

| Very few | 21.1 |

| None | 24.0 |

|

| |

| Anti-inflammatory medications | |

| Almost all | 16.5 % |

| More than half | 29.5 % |

| About half | 15.3 % |

| Less than half | 9.7 % |

| Very few | 15.3 % |

| None | 13.6 % |

|

| |

| Anti-depressant medications | |

| Almost all | 0.6 % |

| More than half | 2.3 % |

| About half | 8.5 % |

| Less than half | 14.1 % |

| Very few | 32.2 % |

| None | 42.4 % |

|

| |

| Anticholinergics (e.g., oxybutynin) | |

| Almost all | 0.6 % |

| More than half | 4.0 % |

| About half | 5.1 % |

| Less than half | 15.3 % |

| Very few | 34.5 % |

| None | 40.7 % |

|

| |

| Anticonvulsants (e.g., neurontin) | |

| About half | 1.7 % |

| Less than half | 2.8 % |

| Very few | 29.5 % |

| None | 65.9 % |

|

| |

| Narcotic pain medications | |

| About half | 0.6 % |

| Less than half | 2.3 % |

| Very few | 21.1 % |

| None | 76.0 % |

|

| |

| Complementary/alternative medicine therapies | |

| Almost all | 1.1 % |

| More than half | 1.7 % |

| About half | 2.8 % |

| Less than half | 10.2 % |

| Very few | 26.1 % |

| None | 58.0 % |

|

| |

| Bladder analgesics (e.g., pyridium) | |

| Almost all | 1.7 % |

| More than half | 2.8 % |

| About half | 5.6 % |

| Less than half | 11.3 % |

| Very few | 25.4 % |

| None | 53.1 % |

|

| |

| 5 Alpha Reductase Inhibitors | |

| Almost all | 0.6 % |

| More than half | 0.6 % |

| About half | 6.3 % |

| Less than half | 6.3 % |

| Very few | 18.9 % |

| None | 67.4 % |

|

| |

| Pelvic floor physical therapy | |

| More than half | 2.3 % |

| About half | 2.3 % |

| Less than half | 4.5 % |

| Very few | 20.5 % |

| None | 70.5 % |

|

| |

| Prostate massage | |

| More than half | 1.7 % |

| About half | 2.8 % |

| Less than half | 2.8 % |

| Very few | 16.5 % |

| None | 76.1 % |

|

| |

| Other | |

| Yes | 4.5 % |

| No | 95.5 % |

Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

Knowledge and Perception of Managing Patients with CP/CPPS

Fully 16% (46/289) were “not at all” familiar with CP/CPPS, and 48% (139/289) were “not at all” familiar with the NIH classification of prostatitis (1)(Table 5). Sixty five percent of respondents (188/289) correctly identified the hallmark symptom of CP/CPPS as pelvic pain. Regarding etiology, 71% (205/289) correctly indicated that the majority of cases of CP/CPPS were non-infectious; however, 37% (107/289) incorrectly indicated that it was caused by a sexually transmitted disease, and 36% (104/289) incorrectly indicated that it was caused by a psychiatric illness. (Table 5).

Table 5.

Physician Knowledge and Perception of Managing Patients with CP/CPPS* (n=289)

| Number of male patients that carry the diagnosis (mean, SD) | 3.39 ± 5.159 |

|

| |

| Familiarity with the condition of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men | |

| Very familiar | 6.6 % |

| Somewhat familiar | 45.6 % |

| A little bit familiar | 31.4 % |

| Not at all familiar | 16.4 % |

|

| |

| The “hallmark” symptom of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome | |

| Pelvic Area Pain (correct answer) | 64.4 % |

| Urinary Frequency | 13.8 % |

| Nocturia | 1.1 % |

| Other | 2.7 % |

| I do not know | 18.0 % |

|

| |

| Familiarity with the NIH classification of prostatitis | |

| Very familiar | 2.2 % |

| Somewhat familiar | 16.4 % |

| A little bit familiar | 33.5 % |

| Not at all familiar | 48.0 % |

|

| |

| The majority of cases of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men are Non-infectious (correct answer) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1.5 % |

| Disagree | 15.2 % |

| Agree | 44.6 % |

| Strongly agree | 26.8 % |

| I don’t know | 11.9 % |

|

| |

| Caused by sexually transmitted diseases (incorrect answer) | |

| Strongly disagree | 14.7 % |

| Disagree | 48.5 % |

| Agree | 20.3 % |

| Strongly agree | 3.8 % |

| I don’t know | 12.8 % |

|

| |

| Caused by psychiatric illness (incorrect answer) | |

| Strongly disagree | 15.5 % |

| Disagree | 49.1 % |

| Agree | 14.3 % |

| Strongly agree | 1.5 % |

| I don’t know | 19.6 % |

Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

We also asked how frequently the PCPs manage patients with other chronic conditions that often have uncertain etiology (Table 6). While the majority of PCPs reported that they frequently manage patients with chronic low back pain, chronic headache, and irritable bowel syndrome, and almost a quarter of PCPs reported frequently managing patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, only about 5% reported frequently managing patients with CP/CPPS.

Table 6.

Reported Frequency of Primary Care Physicians’ Managing Chronic Conditions (n=289)

| Chronic headache | |

| Frequently | 77.4 % |

| Sometimes | 21.5 % |

| Never | 1.1 % |

|

| |

| Chronic low back pain | |

| Frequently | 92.6 % |

| Sometimes | 7.0 % |

| Never | 0.4 % |

|

| |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | |

| Frequently | 23.9 % |

| Sometimes | 67.2 % |

| Never | 9.0 % |

|

| |

| Chronic postatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome | |

| Frequently | 5.6 % |

| Sometimes | 71.3 % |

| Never | 23.1 % |

|

| |

| Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome | |

| Frequently | 7.1 % |

| Sometimes | 75.8 % |

| Never | 17.1 % |

|

| |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Frequently | 61.3 % |

| Sometimes | 38.3 % |

| Never | 0.4 % |

Predictors of Primary Care Physicians’ Responses

Using univariate analyses, we show that there are certain physician characteristics that are significantly associated with the likelihood of (1) having familiarity with CP/CPPS in men (practice setting, male gender, more years of practice, and higher percentage of male patients); (2) having knowledge of the hallmark symptoms of CP/CPPS (male gender); and (3) having knowledge in managing patients with CP/CPPS (male gender, more years of practice, higher percentage of male patients). Table 7 presents only significant associations between physician characteristics and familiarity and knowledge questions.. In the multivariate analyses of primary care physicians’ characteristics and the likelihood of performing various tests and recommending various treatments, results of the logistic regression analysis did not predict any consistent pattern in reporting various tests and recommending various treatments.

Table 7.

Physician characteristics that significantly predict familiarity and knowledge with CP/CPPS* and etiology and symptoms

| Statistic | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician characteristics that significantly predict familiarity with CP/CPPS in men | ||||

| Practice setting | X2= 8.67 | df= 2 | n=268 | 0.013 |

| Gender | X2=38.61 | df=3 | n=270 | 0.000 |

| Years of practice | F=4.26 | df=3 | n=267 | 0.006 |

| Percent of patients that are male | F=12.43 | df=3 | n=266 | 0.000 |

| Physician characteristics that significantly predict knowledge of hallmark symptom of CP/CPPS | ||||

| Gender | X2= 6.63 | df= 1 | n=259 | 0.01 |

| Physician characteristics that predict knowledge about managing patients with CP/CPPS | ||||

| CP/CPPS is non-infectious | ||||

| Years of practice | T=−2.00 | df=158.4 | n=265 | 0.046 |

| Percent of patients that are male | T=−2.27 | df= 262 | n=264 | 0.024 |

| CP/CPPS is caused by STD | ||||

| Gender | X2=6.48 | df=1 | n=264 | 0.011 |

| Percent of patients that are male | T=−2.74 | df=259 | n=261 | 0.007 |

Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of physician practices, including approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients is fundamental to both the development and evaluation of continuing medical education, medical school curricula, and national educational programs. The emerging recognition of CP/CPPS as an important medical condition was the impetus for us to survey the diagnostic, treatment, and management patterns of primary care physicians in the United States.

Our study showed that many PCPs reported little or no familiarity with CP/CPPS, have important knowledge deficits, and have limited experience in managing men with this syndrome. Over one-third of PCPs reported never having seen a patient like the one with CP/CPPS described in the vignette. PCPs reported practice patterns regarding diagnosis and treatment of CP/CPPS, which are not supported by evidence, such as ordering prostate-specific antigen tests and prescribing antibiotics. In order to effectively diagnose and treat CP/CPPS, physicians need to understand the NIH classification system for prostatitis; however, PCPs reported little or no familiarity with this classification scheme.

Two previous survey studies done 10 and 15 years ago, respectively, were from Canada (16) and the Netherlands. The only study done in the United States, done 10 years ago, was from one county in the state of Wisconsin (15). Previous studies did not specifically ask primary care physicians about chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, but instead referred to “prostatitis” in general. We were particularly interested in surveying physicians about new cases of CP/CPPS, as this is an important current research area. It is unclear whether the management of men with newly diagnosed CP/CPPS should vary from men with longstanding, treatment refractory CP/CPPS. Unlike the previous studies, we used a clinical vignette to be certain that primary care physicians were aware that our questions pertained to men with a specific type of prostatitis, namely CP/CPPS.

While studies suggest that the symptoms of CP/CPPS are common in the community(11, 23), and that 1% of all visits to primary care physicians are for the diagnosis “prostatitis”(24), our data indicated that fully 38% (110/289) of PCPs reported never having seen a patient like the one with CP/CPPS described in the vignette. In addition, 16% (46/289) reported being “not at all” familiar with the condition, CP/CPPS. Furthermore, PCPs in our study reported infrequently managing men with CP/CPPS; they reported more frequently managing other chronic pain conditions, such as chronic headache, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis, which do not appear to have correspondingly higher population-based prevalence than CP/CPPS. Whether these findings represent a large pool of men with CP/CPPS who do not seek care or seek care directly from urologists, or whether men who visit primary care physicians may not volunteer their CP/CPPS symptoms or PCPs may not feel comfortable discussing them cannot be determined from our survey. It is also possible that CPPS is less common than we think, as most visits for “prostatitis” identified in studies such as the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey studies(24) may not reflect CP/CPPS. Lastly, it could be that our sample of PCPs for this study may not be truly representative of PCPs in the community.

Responding physicians also reported varying practice patterns regarding diagnosis, referral, and treatment, and reported important knowledge deficits. Approximately half of the physicians in our survey study were “not at all” familiar with the classification of prostatitis, which is a fundamental tenet to caring for men with CP/CPPS, and should be a key feature of any educational outreach efforts to PCPs. Our finding that almost one-third of primary care physicians did not correctly respond that the etiology of CP/CPPS is non-infectious, coupled with the finding that antibiotics were (inappropriately) the most common prescribed therapy, also suggest an essential need to educate PCPs. Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis, which are infectious diseases, need to be differentiated from chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, which likely does not have an infectious etiology. In addition, approximately one-third of primary care physicians incorrectly reported that CP/CPPS is caused by psychiatric illness. Improved education of PCPs about CP/CPPS may help change this potentially damaging perception that the chronic pelvic pain in men is psychogenic. Finally, there is a potential for harm (i.e., unnecessary anxiety, prostate biopsies) to men with symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS by the inappropriate ordering of PSA tests, which our study showed was a common practice, yet there is no evidence to support this practice(19, 20).

Understandably a big challenge to managing men with CP/CPPS remains the fact that there is neither a gold standard diagnostic test nor proven effective treatment (25); therefore, there lacks an evidence-based clinical guideline to help primary care physicians in the management of this condition. Meanwhile, ongoing clinical trials funded by the NIDDK seek to identify new and effective treatments for men with CP/CPPS (www.uppcrn.org). Research is also underway to elucidate the natural history, etiology, and pathophysiology of this condition, such that early identification and intervention in primary care may result in improved outcomes for patients.

Another reason for educating primary care patients about CP/CPPS is that this condition is among those that cause chronic nonmalignant pain, an important new topic in primary care medicine (26). Since most primary care physicians are not comfortable treating patients with chronic nonmalignant pain, educational efforts are underway to increase PCPs’ willingness to manage patients with chronic pain. Educational efforts about chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men could serve as a useful model of a chronic nonmalignant pain condition, during medical training, including medical school, residency, fellowship, and continuing medical education courses.

Our study has several limitations. First, although our response rate of 52% is typical of physician surveys(27), response bias is a possibility. Secondly, our study population was chosen by convenience sampling, therefore, our findings warrant replication in a larger, more representative sample. Thirdly, the data on the practice patterns of PCPs were based on physician self-report and may not match actual practice. Fourthly, the associations between the physician characteristics and management practices must be viewed with caution, given that multiple tests of association were performed.

In conclusion, the results of this multi-center, primary care physician survey study suggest that educational efforts on the care of patients with CP/CPPS should target PCPs, especially since pain is now considered the hallmark symptom of this syndrome and diagnosis, treatment, and management of chronic nonmalignant pain in primary care practice has become a national health care priority.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source: This research was funded by grants (U01 DK65187, DK 65277, and DK 65257) from the National Institutes of Health, which had no other role in the design or conduct of the study, or preparation of the manuscript.

Financial Support: This research was funded by grants (U01 DK65187, DK 65277, and DK 65257) from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank all the participating primary care physicians for making this study possible.

References

- 1.Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Jr, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282(3):236–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Bostwick DG, Jacobsen SJ. A review of clinical and pathological prostatitis syndromes. Urology. 1997;49(6):809–21. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett B, Richardson P, Gardner W. Histopathology and cytology of prostatitis. In: Lepor H, Lawson R, editors. Prostate Diseases. Philadelphia: WB Saunders and Co.; 1993. pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, Clark J. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol. 2001;165(3):842–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a community based cohort of older men. J Urol. 2002;168(6):2467–71. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Bostwick DG, Jacobsen SJ. Prevalence of a physician-assigned diagnosis of prostatitis: the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status Among Men. Urology. 1998;51(4):578–84. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keeffe Rosetti MC, Gao SY, Calhoun EA. Incidence and clinical characteristics of National Institutes of Health type III prostatitis in the community. J Urol. 2005;174(6):2319–22. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000182152.28519.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary MP, et al. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):656–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner JA, Ciol MA, Von Korff M, Berger R. Health concerns of patients with nonbacterial prostatitis/pelvic pain. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):1054–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calhoun EA, McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, et al. The economic impact of chronic prostatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1231–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNaughton Collins M, Pontari M. Prostatitis. In: Litwin M, Saigal C, editors. Urologic Diseases in America. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office; 2007. pp. 9–41. NIH Publication No. 07-5512. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger JN, Egan KJ, Ross SO, Jacobs R, Berger RE. Chronic pelvic pains represent the most prominent urogenital symptoms of “chronic prostatitis” . Urology. 1996;48(5):715–21. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00421-9. discussion 721–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162(2):369–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Rosette JJ, Hubregtse MR, Karthaus HF, Debruyne FM. Results of a questionnaire among Dutch urologists and general practitioners concerning diagnostics and treatment of patients with prostatitis syndromes. Eur Urol. 1992;22(1):14–9. doi: 10.1159/000474715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon TD. Questionnaire survey of urologists and primary care physicians’ diagnostic and treatment practices for prostatitis. Urology. 1997;50(4):543–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickel JC, Nigro M, Valiquette L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of prostatitis in Canada. Urology. 1998;52(5):797–802. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SPSS program]. Version 15. SPSS, Inc

- 18.Collins MM, Barry MJ, Bin L, Roberts RG, Oesterling JE, Fowler FJ. Diagnosis and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Practice patterns of primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(4):224–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadler RB, Collins MM, Propert KJ, et al. Prostate-specific antigen test in diagnostic evaluation of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2006;67(2):337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaeffer AJ. Clinical practice. Chronic prostatitis and the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1690–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp060423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander RB, Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Ciprofloxacin or tamsulosin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(8):581–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weidner W. Treating chronic prostatitis: antibiotics no, alpha-blockers maybe. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(8):639–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu JC, Link CL, McNaughton-Collins M, Barry MJ, McKinlay JB. The association of abuse and symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: results from the Boston Area Community Health survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1532–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0341-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins MM, Stafford RS, O’Leary MP, Barry MJ. How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol. 1998;159(4):1224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNaughton Collins M, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic abacterial prostatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(5):367–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S. Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(2):93–100. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellerman S, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]