Abstract

A convergent and highly stereocontrolled total synthesis of the cytotoxic macrolide (+)-superstolide A is described. Key features of this synthesis include the use of bimetallic linchpin 36b for uniting the C(1)-C(15) (43) and the C(20)-C(27) (38) fragments of the natural product, a late-stage Suzuki macrocyclization of 49, and a highly diastereoselective transannular Diels-Alder reaction of macrocyclic octanene 4. In contrast, the intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction of pentaenal 5 provided the desired cycloadduct with lower stereoselectivity (6:1:1).

Introduction

In 1994 Minale and co-workers reported the isolation and structural determination of superstolides A (1) and B (2), from the New Caledonian sponge Neosiphonia superstes.1,2 The superstolides are highly cytotoxic against several cancer cell lines including murine P388 leukemia cells (IC50 = 3 ng/mL for both 1 and 2), human nasopharyngeal cells (IC50 = 5 ng/mL for 2), and non-small-cell lung carcinoma cells (IC50 = 4 ng/mL for both 1 and 2). Due to their interesting chemical structures and potent biological properties, the superstolides have attracted considerable attention as synthetic targets. Efforts towards the C(21)-C(26) fragment have been reported by D’Auria,3 Jin,4 Romea,5 Paterson,6 Marshall,7 as well as our group.8 In 1996 we published a highly diastereoselective synthesis of the cis-fused octahydronaphthalene nucleus,9 and a few years later Jin and co-workers reported a different approach towards this part of the molecule.10 Recently, we reported the first total synthesis of (+)-superstolide A11 by a route that proceeds via the transannular Diels-Alder reaction of macrocyclic octaene 4, an element of the synthesis that is presumably biomimetic in nature.12,13 We report herein a full account of the evolution of the synthetic strategy that led to the successful synthesis of 1, and of the difficulties that were encountered along the way.

Synthetic Strategy

From the outset of our work on superstolide A, we intended to synthesize the highly-substituted cis-octahydronaphthalene unit by a Diels-Alder reaction performed in either the intramolecular (IMDA)9 or transannular (TDA) mode.8a We established in early studies that the IMDA reaction of a model substrate provided the cis-octahydronaphthalene nucleus with 6:1:1 selectivity.9 Although this was a promising result, a plan to pursue a transannular Diels-Alder reaction of the 24-membered octaene 4 also seemed attractive since several TDA reactions are known to be much more stereoselective than analogous IMDA cyclizations.14 We have successfully demonstrated this principle in several syntheses,15,16 and superstolide A provided another challenging test case to explore the generality of this concept. We recognized that there were several possible TDA reactions that could occur within macrocycle 4, however we anticipated that the proposed cyclization would predominate owing to the favorable kinetics of closure of a 6-membered ring at C(9)-C(14). While a 6-membered ring could also be closed by a TDA reaction of a C(2,3)-dienophile and a C(18–21)-diene, this cyclization would require the lactone to adopt a disfavored s-cis conformation. IMDA reactions of substrates with esters in the connecting chain are generally highly disfavored.14,17 Although the proposed transannular cyclization offered potential advantages in terms of stereoselectivity, we were aware of the chemical sensitivity of the two conjugated tetraene units of 4.

Therefore, we designed a strategy that would allow us to adjust the timing of the Diels-Alder reaction relative to the macrocyclization step late in the synthesis (i.e. use of 3 vs 4 as key intermediates, Scheme 1). On the basis of this analysis, we targeted functionalized pentaenal 5 as a common precursor to 3 and 4. In the synthetic direction, the aldehyde unit of 5 could be transformed into a vinylmetal intermediate capable of being coupled with iodide 6, either prior to or after the Diels-Alder reaction. Finally, pentaenal 5 could be assembled by coupling of suitably functionalized fragments 7–9, via olefination of 8 and 9 followed by a metal catalyzed cross-coupling reaction with 7.18

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Allylic Alcohols 7a, b

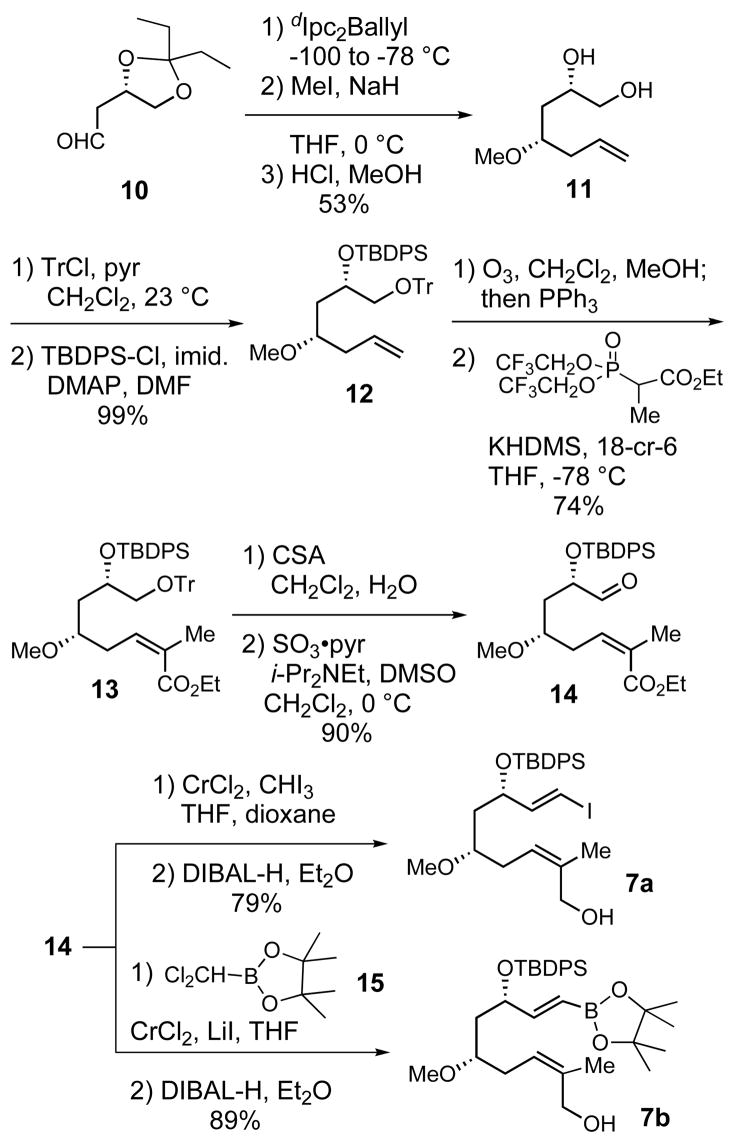

The synthesis of allylic alcohols 7a, b started with the asymmetric allylation (96:4 d.r.) of known aldehyde 10, using Brown’s dIpc2Ballyl reagent under salt free conditions (Scheme 2).19 O-Methylation of the resulting secondary alcohol followed by ketal hydrolysis afforded diol 11 in 53% yield over three steps. Selective formation of the primary trityl ether followed by protection of the secondary hydroxyl group gave triether 12. After ozonolysis of the double bond of 12, the resulting aldehyde was subjected to Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination according to the Still-Gennari20 procedure, which afforded (Z)-enoate 13 in 74% over four steps. Deprotection of the primary trityl ether of 13 followed by oxidation of the resulting alcohol using Parikh-Doering conditions provided aldehyde 14 (90%).21 This intermediate was elaborated to vinyl iodide 7a (79%) and vinylboronate 7b (89%) by using Takai22 or modified Takai23 conditions followed by DIBAL-H reduction of the ester.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Allylic Alcohols 7a–b

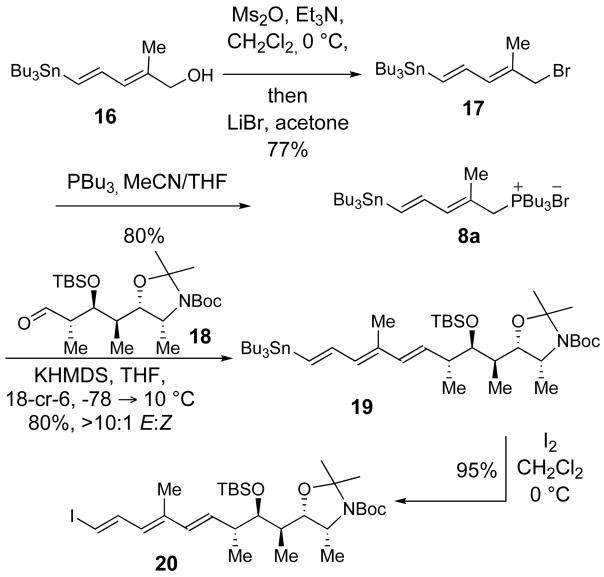

Synthesis of Trienyl Iodide 20

Trienyl iodide 20 was synthesized from the known allylic alcohol 1624 as outlined in Scheme 3. Evans had previously reported the conversion of 16 to the dienylic bromide 17 using carbon tetrabromide and triphenylphosphine.24 This reaction provided bromide 17 in variable yield and purity, therefore a much cleaner method with higher and more reliable yields was developed. The dienylic mesylate was generated by treatment of 16 with methanesulfonic anhydride and triethylamine in dichloromethane at 0 °C. The reaction was then diluted with acetone and lithium bromide was added at 23 °C to effect SN2 displacement giving dienylic bromide 17 in 77% yield. Treatment of 17 with PBu3 in a mixture of CH3CN and THF provided phosphonium salt 8a. The Wittig reaction of the ylide generated from phosphonium salt 8a and aldehyde 188b furnished trienyl stannane 19 in 80% yield with (E)-selectivity greater than 10:1. Initially, we had considered using Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons and Julia olefination sequences for the synthesis of trienyl stannane 19. However, these strategies were ultimately abandoned due to the low yields and poor stereoselectivities realized in the synthesis of (E, E, E)-triene 19 by using these reactions.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Trienyl Iodide 20

Trienyl stannane 19 was a viable Stille cross-coupling partner for 7a, but conversion to iodide 20 would be required for cross-coupling with vinylboronate 7b. Careful titration of trienyl stannane 19 with one equivalent of iodine afforded 20 in 95% yield. Iodide 20 was found to be very sensitive, with olefin isomerization occurring if any excess of iodine was used in the reaction with 19, and product decomposition occurred during attempted chromatographic purification of 20 on silica gel or alumina.

IMDA Approach: Initial Studies

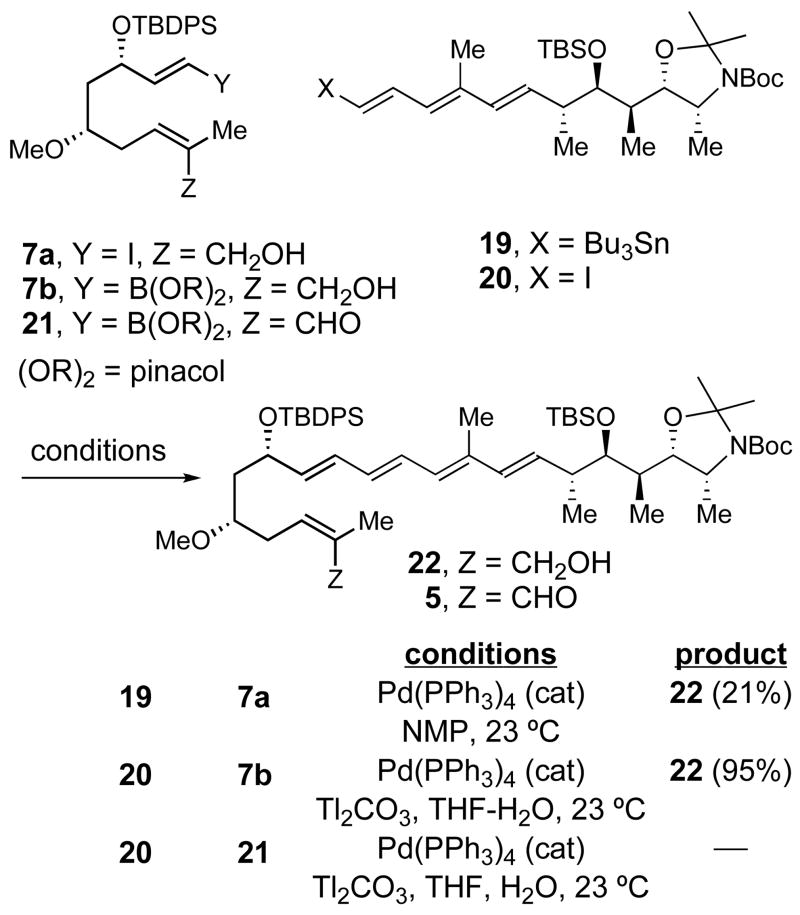

With all the cross-coupling partners in hand, we looked for optimal conditions for the fragment assembly (Scheme 4). Treatment of a mixture of iodide 7a and trienyl stannane 19 with catalytic Pd(PPh3)4 furnished allylic alcohol 22 in low yield (21%).25 In contrast, the Suzuki cross-coupling between 7b and 20 in the presence of thallium (I) carbonate26 gave 22 in excellent yield (95%). Hoping to minimize the manipulations of this sensitive intermediate, we attempted to use enal 21 in a Suzuki coupling with 20 but, unfortunately, this reaction was unsuccessful.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the IMDA precursor 22

Oxidation of allylic alcohol 22 with SO3-pyridine21 afforded 5, which was then subjected to the intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction conditions previously developed in our group for the superstolide synthesis.9 Specifically, heating a solution of 5 in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol at 70 ºC gave a ca. 6:1:1 mixture of products favoring the endo adduct 23 (65%).27

The relative stereochemistry of the cis-fused bicyclic octahydronaphthalene unit of 23 was assigned based on nOe interactions between H(9), H(10), H(14), H(17) and Me(30) (Figure 2). This assignment is in agreement with the nOe’s measured on the natural product1 and the results observed in the intramolecular Diels-Alder studies of model substrates.9

Figure 2.

1H nOe interactions in the IMDA adduct 23

Aldehyde 23 was subjected to modified Takai conditions23 using dichloromethylboronate 1528 to provide pinacol vinylboronate 24 in 95% yield (Scheme 6). With 24 in hand, we focused on the synthesis of its cross-coupling partner (Scheme 7). Aldehyde 2729 was subjected to Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination using phosphonate 2830 to give enoate 29 (77%). Treatment of 29 with iodine in CH2Cl2 provided iodide 6 in 61% yield.

Scheme 6.

Elaboration of the IMDA adduct 23

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of iodide 6

Treatment of a mixture of 24 and 6 in wet THF with thallium(I) carbonate26 and catalytic Pd(PPh3)4 furnished the trienoate ester 3 in 66% yield (Scheme 6). We thought this intermediate would undergo global silyl deprotection upon treatment with a suitable fluoride source. However, treatment of 3 with TAS-F afforded 25 with a TBS ether remaining on C(23).31 Unfortunately, further attempts to effect global deprotection with a model substrate failed under a variety of conditions. It was clear from these results that the macrocyclization substrate must have an easily removable protecting group on C(23)-OH. Accordingly, we decided to protect C(23)-OH as a triethylsilyl ether. Accordingly, aldehyde 26 was synthesized following the same sequence shown for the TBS ether 23. However, despite considerable efforts, we were unable to accomplish the Takai olefination of this intermediate with 15 to give the corresponding pinacol vinylboronate.

Synthesis of iodo boronate 30

Due to the difficulties encountered in Scheme 6, we decided to install the vinylboronate unit prior to the IMDA cycloaddition. We thought 30 would be a suitable intermediate for joining the different fragments of the molecule (Scheme 8). Importantly, this modified strategy would still allow us to establish the octahydronaphthalene unit via an intramolecular or transannular Diels-Alder reaction.

Scheme 8.

Revision of the Synthetic Strategy

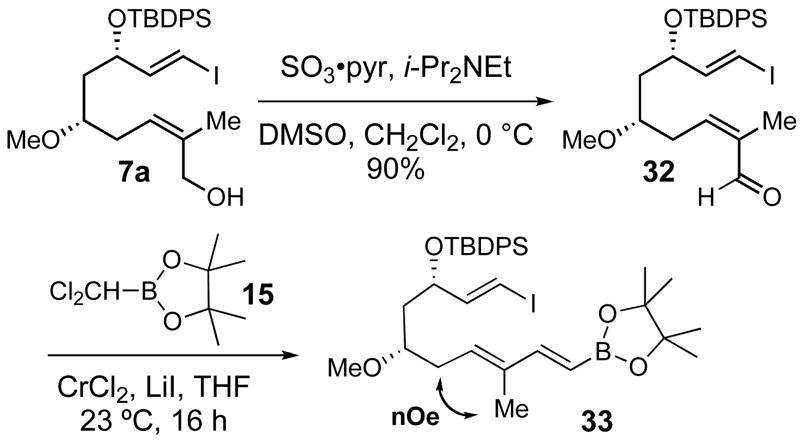

Oxidation of alcohol 7a under Parikh-Doering conditions21 provided aldehyde 32 in 90% yield (Scheme 9). Surprisingly, the Takai olefination of 32 with dichloromethylboronate 15 resulted in complete Z/E isomerization of the (Z)-trisubstituted double bond to give (E)-33 as a single isomer. Since only one boronic ester was isolated from the Takai olefination, this isomerization was not suspected in our initial trials, in which aldehyde 32 was used directly as the crude product from oxidation of 7a. However, silica gel chromatographic purification of 32 provided material that was a 70:30 Z:E mixture of enals. When this mixture was subjected to Takai olefination with 16, 33 was again obtained as a single (E) product, as determined by nOe analysis.

Scheme 9.

Unexpected Z/E isomerization during Takai olefination of 32

We also tried to introduce the vinylboronate moiety through a hydroboration reaction of an alkyne derived from 32. However, despite extensive efforts to convert 32 to the requisite enyne (Seyferth-Gilbert,32 trimethylsilyldiazomethane33 and Corey-Fuchs34 conditions), we were unable to devise a high yielding and highly stereoselective synthesis of the enyne and this approach was ultimately abandoned. Here again, isomerization of the trisubstituted olefin was a significant complication.

Second Generation Strategy

At this point, it became apparent that a different strategy was required to construct the C(1)-C(7) fragment of superstolide A. The new approach was designed to proceed from the four building blocks 35–38 (Scheme 10). Again, we intended that the timing of the Diels-Alder reaction relative to the macrocyclization event could be adjusted late in the synthesis. We thought a Wittig reaction between phosphonium salt 35 and aldehyde 37 could avoid the isomerization of the labile (Z)-trisubstituted double bond C(8)-C(9) demonstrated in Scheme 9. Although we had already developed a synthesis of the Suzuki cross-coupling partner 20 (Scheme 3), the sequence proved not to be highly reproducible on a multigram scale. Therefore, use of the bifunctional linchpin 36 with orthogonal cross-coupling functional groups was considered for synthesis of the C(14)-C(21) tetraene.35

Scheme 10.

Second Generation Retrosynthesis of Superstolide A

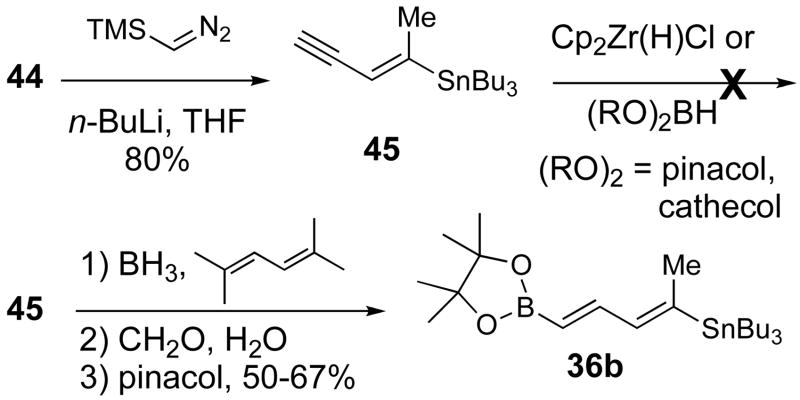

Development of a Bimetallic Diene Linchpin

The bifunctional linchpin 36 was designed such that the two termini would bear functional groups capable of undergoing sequential cross coupling reactions. Initially vinylsilane/vinylstannane 36a and vinylboronate/vinylstannane 36b were targeted (Scheme 11). Vinylsilane 36a was prepared by olefination of 4429 using lithiated bis(trimethylsilyl)methane,36 albeit in low yield. Other bases were screened for deprotonation of bis(trimethylsilyl)methane (methyllithium, tert-butyllithium, TMEDA as additive) but with no improvement in reaction efficiency.

Scheme 11.

Studies on the Synthesis of a Bimetallic Linchpin

The homologation of aldehyde 44 to the vinylboronate 36b was also problematic. Olefination under Takai conditions using pinacol dichloromethylboronate gave 36b with no Z/E selectivity, and use of bis(1,3,2-dioxaborin-2-yl)methane37 was hampered by the difficulty and unpredictability of its preparation.

We also hoped that homologation of aldehyde 44 to alkyne 45 would allow opportunities for hydrometallation (Scheme 12). Alkyne 45 was prepared from aldehyde 44 by treatment with lithiotrimethylsilyldiazomethane.33 Unfortunately, attempted hydrozirconation of 45 using the Schwartz reagent38 did not give the desired compound and hydroboration with catechol or pinacol borane were also unsuccessful. Gratifyingly, hydroboration of 45 according to Snieckus’ procedure39 provided 36b in good yield (50–67%).

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of Bimetallic Linchpin 36b

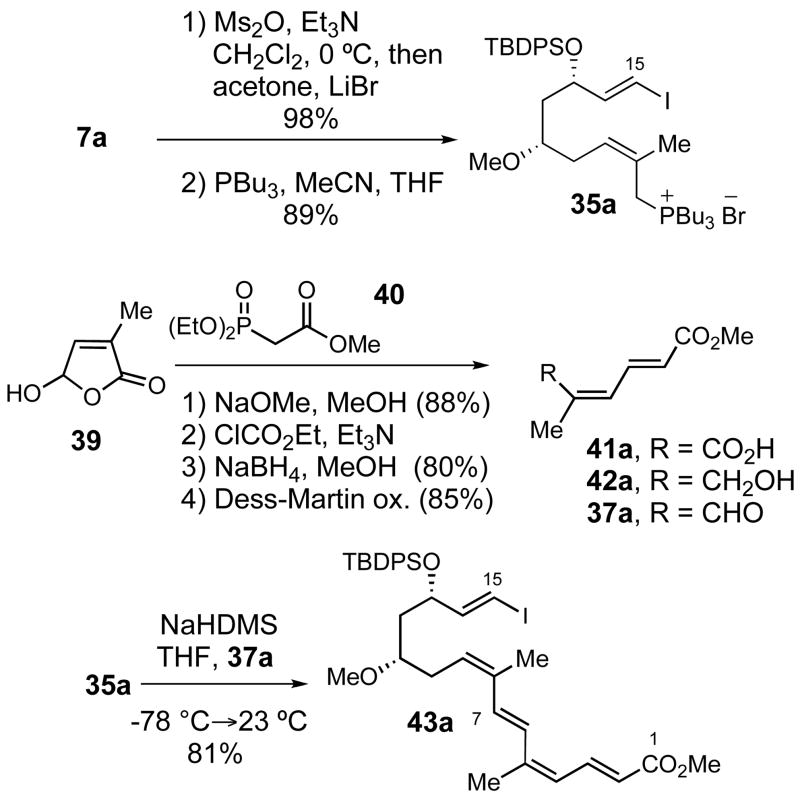

Synthesis of Pentaenoate 43a

Phosphonium salt 35a was synthesized from alcohol 7a by conversion to the corresponding allylic bromide (98%) followed by treatment with PBu3 (89%, Scheme 13). The synthesis of the aldehyde coupling partner 37a started from hydroxybutenolide 39.40 Horner- Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of 39 with the β-phosphonoester 40 provided 41a (72%). Reduction of the carboxylic acid via the mixed anhydride followed by oxidation of the primary alcohol using the Dess-Martin periodinane41 gave 37a in 68% yield. This aldehyde was then coupled with phosphonium salt 35a to provide the isomerically pure pentaenoate 43a in 81% yield.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis and Wittig coupling of 35a and aldehyde 37a

Synthesis of the C(16)-C(27) Fragment 47

Vinylboronate 47 was synthesized starting from alcohol 46 (Scheme 14).8b Temporary protection of C(25)-OH of 46 as a TES ether followed by ozonolysis of the alkene provided the corresponding aldehyde. Treatment of this intermediate with CrCl2-CHI3,22,42 and deprotection of C(25)-OH gave 38 in 79% yield over four steps. Attempted Stille cross-coupling reaction between 38 and bimetallic linchpin 36b, using catalytic Pd2(dba)3 and AsPh3 in THF at 50 ºC,43 gave only decomposition of the bimetallic fragment. However, treatment of 38 and 36b with catalytic Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 in DMF afforded vinylboronic ester 47 in 50–60% overall yield.44

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of the C(16)-C(27) Fragment 47

Fragment Assembly and Total Synthesis of Superstolide A

With tetraenoate 43a and vinylboronic ester 47 in hand, we envisioned two possible ways to combine the two fragments: a Suzuki cross coupling reaction followed by a macrolactonization (path a, Scheme 15) or a cross-esterification prior to the Suzuki reaction (path b, Scheme 15). Path a initially seemed more attractive to us since intermediate 48 would be a suitable precursor to test both the intramolecular and transannular Diels- Alder cycloadditions.

Scheme 15.

Fragment Assembly Strategies

Treatment of 43a and 47 in wet THF with TlOEt and catalytic Pd(PPh3)4 provided isomerically pure polyunsaturated ester 48 in 62% yield (Scheme 16).45 Heating a solution of 48 in CF3CH2OH resulted in decomposition probably due to acidity of the solvent. When the IMDA reaction of 48 was attempted in toluene, the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product showed low conversion and decomposition of 48. Slightly better results (ca. 40% of a mixture of diastereomers) were obtained by treatment of 48 with Otera’s catalyst 52,46 but there was evidence that 48 decomposed upon heating.

Scheme 16.

Macrolactonization Pathway for Superstolide Synthesis

Deprotection of the methyl ester of 48 by treatment with KOSiMe3 gave seco acid 50.47 Although in some trials we could obtain isomerically pure 50, this reaction was not reproducible, and inseparable mixtures of compounds derived from isomerization of the labile C(2)-C(9) tetraenoate unit were usually obtained. Pure carboxylic acid 50 was subjected to macrolactonization conditions. Unfortunately, treatment of 50 under Yamaguchi conditions48,49 or with 2-methyl-6-nitrobenzoic anhydride50 gave a complex mixture of products.

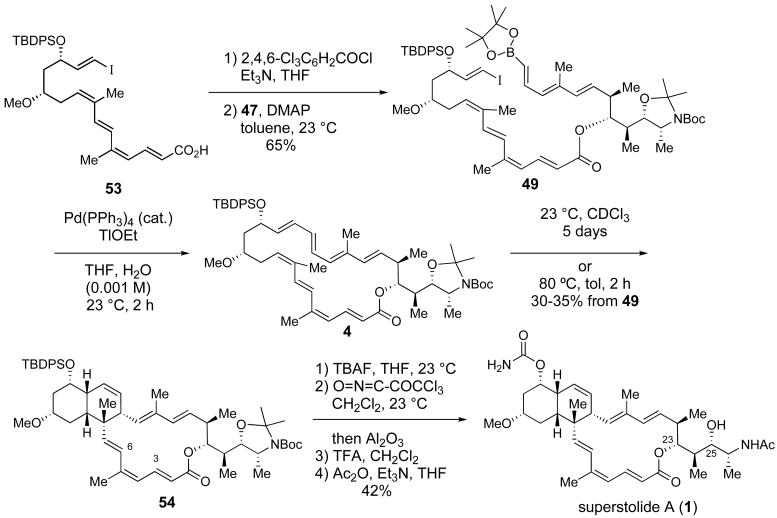

After this result, we turned our attention to the approach shown in path b. Not surprisingly after the difficulties encountered with 48, attempted deprotection of methyl ester 43a was problematic (Scheme 17). Under various ester cleavage conditions, we obtained 50 as mixtures of E/Z isomers at the C(8)-C(9) trisubstituted alkene. It was clear that synthesis of this sensitive substrate would require a different protecting group strategy for the carboxylic acid of immediate precursors. Accordingly, we elected to use a β-trimethylsilylethyl ester. Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of hydroxybutenolide 3940 and β-phosphonoester 2830 afforded 41b in 76% yield. Reduction of the carboxylic acid via the mixed anhydride followed by oxidation of the dienylic alcohol using Dess-Martin conditions41 provided aldehyde 37b in 85% yield. Wittig olefination of this aldehyde using phosphonium salt 35a provided ester 43b (87%). Selective deprotection of the ester by treatment with TASF in DMF gave carboxylic acid 53 as a single isomer in 75% yield.51

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of carboxylic acid 53

Coupling of the carboxylic acid 53 and alcohol 47 by using the Yamaguchi esterification procedure48,49 (53, trichlorobenzoyl chloride, Et3N, then 47 and DMAP) gave ester 49 in 65% yield (Scheme 18). Treatment of a 0.001 M solution of 49 in wet THF with TlOEt and catalytic P(PPh3)4 effected an intramolecular Suzuki reaction that provided the macrocyclic octaene 4 (35–40%).52 We also isolated products believed to arise from bimolecular cross coupling of 49. Gratifyingly, macrocycle 4 underwent a highly diastereoselective transannular Diels-Alder cyclization at 23 ºC over 5 days, or in 2 h at 80 ºC, to give 54 as the only observed cycloadduct in 30–35% overall yield (two steps from 49). Interestingly, 1H NMR analysis of 54 at 23 ºC showed doubling of the 1H resonance for many protons in the vicinity of the N-Boc unit, but also distal protons including H(3) and H(6). This observation suggested that 54 exists as a dynamic mixture of N-Boc rotamers along with conformational isomers within the newly formed 16-membered ring; this deduction was confirmed by variable temperature 1H NMR studies.

Scheme 18.

Completion of the Total Synthesis of Superstolide A

Elaboration of 54 to superstolide A proceeded smoothly (Scheme 18). Removal of the TBDPS ether by treatment with TBAF followed by treatment of the resulting alcohol with trichloroacetyl isocyanate53 installed the carbamate moiety at C(13) in 65% yield from 54. Finally, treatment of the resulting carbamate with TFA, to remove the Boc and acetonide protecting groups, followed by addition of Ac2O and Et3N provided synthetic (+)-superstolide in 42% yield from 54. Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR data of synthetic and natural superstolide A showed excellent agreement.1

Summary

We have achieved the first total synthesis of (+)-superstolide A by a convergent and highly stereoselective sequence. Highlights of this work include an intramolecular Suzuki coupling reaction and a highly stereoselective transannular Diels-Alder cycloaddition of 4 to assemble the tricyclic skeleton of superstolide A. This work demonstrates that conformational preferences imposed by the macrocycle improve the stereoselectivity of the key Diels-Alder step, since conventional intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition of 5 gives a 6:1:1 mixture of three cycloadducts. Additionally, the example described herein expands the number of successful applications of Suzuki macrocyclizations to highly functionalized late-stage intermediates in the total synthesis of complex natural products.52

A significant part of our efforts in this synthetic venture concerned the efficient and stereoselective synthesis of polyene fragments. Many of the late-stage intermediates were extremely sensitive toward acid, base or even storage which required the optimization of each individual transformation to avoid isomerization of the double bonds. The solutions found, as well as the synthetic strategies described herein, should be useful for the synthesis of superstolide analogs and other polyene containing macrolactones.

Experimental Section.54

Synthesis of Ester 49

To a 0 ºC solution of vinyl iodide 43b (167 mg, 0.217 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (2 mL) was added TAS-F (0.62 mL of a 0.5 M solution in DMF freshly prepared, 0.31 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and quenched with 10% aq. NaHCO3 (0.5 mL). Water (2 mL) and EtOAc (5 mL) were added. The organic phase was washed with water (2 × 2 mL) and brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to afford carboxylic acid 53 (109 mg, 0.163 mmol, 75%) as a colorless oil, which was immediately used in the next reaction.

To a solution of the crude acid 53 (133 mg, 0.198 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added triethylamine (0.14 mL, 0.99 mmol) followed by 2,4,6-trichlorobenzoyl chloride (50 μL, 0.32 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. Hexanes (3 mL) were added and the slurry was filtered through Celite and concentrated. The crude product was dissolved in toluene (2 mL) and was added to a solution of alcohol 47 (93 mg, 0.18 mmol) and DMAP (98 mg, 0.80 mmol) in toluene (2 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature, diluted with EtOAc (4 mL) and poured into water (4 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 4 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Purification by flash chromatography (1 g Davisil™, 5% EtOAc/hexanes) afforded ester 49 (128 mg, 0.109 mmol, 61%) as a yellow oil. The isolated product was contaminated with a small amount of 47 and was immediately used in the next reaction without further purification: 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.76 (ddd, J = 14.4, 12.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.63-7.59 (m, 4H), 7.43-7.30 (m, 7H), 6.87 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (dd, J = 14.4, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.09 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 5.76-5.69 (m, 1H), 5.51 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.39 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (td, J = 7.5, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (m, 1H), 3.98-3.95 and 3.81-3.78 (2 m, 1H combined), 3.68 (ddd, J = 10.0, 8.1, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.32-3.27 (m, 1H), 3.19 (s, 3H), 2.63-2.55 (m, 1H), 2.40-2.25 (m, 2H), 2.07-2.00 (m, 1H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H), 1.88 (s, 3H), 1.79-1.72 (m, 1H), 1.60-1.50 (m, 1H), 1.57 and 1.52 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.47 and 1.41 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.45 and 1.44 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.11 and 1.07 (2 d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H combined), 1.07-1.04 (m, 3H overlapped), 1.05 (s, 9H), 0.91 and 0.88 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 166.2, 151.7, 151.4, 148.5, 146.4, 142.6, 139.2, 139.0, 138.9, 136.2, 136.1, 135.6, 135.5, 134.4, 134.1, 134.0, 133.8, 132.2, 130.1, 129.3, 129.0, 128.5, 124.9, 121.1, 121.0, 93.3, 92.5, 82.9, 79.2, 78.8, 77.7, 77.3, 77.0, 76.9, 75.6, 75.5, 74.2, 56.0, 54.9, 54.7, 42.2, 41.2, 41.1, 34.4, 34.2, 31.6, 30.1, 28.6, 28.4, 27.6, 27.2, 25.1, 24.95, 24.91, 23.9, 21.0, 20.3, 19.5, 17.5, 17.4, 14.1, 13.4, 12.9, 9.8, 9.5 [note: the carbon attached to boron was not observed due to quadrupole broadening caused by the 11B nucleus]; IR (neat) 2977, 2934, 2280, 1698, 1609, 1455, 1428, 1391, 1342, 1254, 1145, 1106, 993, 703 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z for C63H91BINO9SiNa [M + Na]+ calcd 1194.5504, found 1194.5502.

Suzuki Macrocyclization of 49 and Transannular Diels-Alder Reaction of 4: Synthesis of Cycloadduct 54

To a solution of ester 49 (120 mg, 0.102 mmol) in degassed THF:H2O (3:1) (100 mL, 3 freeze-pump-thaw cycles) was added a solution of Pd(PPh3)4 (17 mg, 0.01 mmol) in THF (1 mL) followed by TlOEt (14 μL, 0.20 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h, then was filtered through Celite and poured into water (20 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was filtered through a short pad of Davisil™ (5% EtOAc-hexane, with 2% Et3N) to afford macrocyclic octaene 4, which was immediately used in the next reaction without further purification: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.75-7.60 (m, 4H), 7.45-7.30 (m, 6H), 6.60 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (dd, J = 14.8, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (dd, J = 15.3, 12.2 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (dd, J = 17.1, 14.3 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 5.65 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (app td, J = 15.3, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.47-5.32 (m, 3H), 5.06 and 5.04 (2 dd, J = 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H combined), 4.07 (m, 1H), 3.99 and 3.83 (2 m, 1H combined), 3.71 (m, 1H), 3.04 (s, 3H), 2.97 (m, 1H), 2.33 (m, 2H), 2.18 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 1.96 (s, 3H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.56 and 1.51 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.45 (m, 1H overlapped), 1.45-1.43 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.38 and 1.35 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.14 and 1.12 (2 d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H combined), 1.08-1.03 (m, 3H), 0.95 and 0.93 (2 d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H combined).

A solution of the crude macrolactone 4 and BHT (1 crystal) in toluene (54 mL, 0.001M) was degassed (3 freeze-pump-thaw cycles), heated at 80 ºC for 2 h and then concentrated in vacuo. Purification of the crude product by flash chromatography (0–5% EtOAc-CH2Cl2) afforded 54 (31 mg, 0.034 mmol, 33% two steps) as a colorless oil: [α]25 D = +58.0º (c 0.70, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70-7.68 (m, 4H), 7.44-7.35 (m, 6H), 7.06 and 7.05 (2 dd, J = 15.5, 10.4 Hz, 1H combined), 6.60 and 6.59 (2 d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H combined), 6.10 and 6.09 (2 d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H combined), 6.00 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 5.86 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 5.73 and 5.72 (2 d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H combined), 5.64 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 5.57 and 5.56 (2 d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (dt, J = 10.3, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 5.37 and 5.34 (2 dd, J = 15.3, 9.7 Hz, 1H combined), 4.96 and 4.95 (2 dd, J = 10.5, 3.6 Hz, 1H combined), 3.95 and 3.79 (2 qd, J = 6.0, 4.6 Hz, 1H combined), 3.88 and 3.85 (2 dd, J = 10.5, 4.5 Hz, 1H combined), 3.69 (dt, J = 11.6, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (s, 3H), 3.06 (br d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (tt, J = 11.1, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.49-2.39 (m, 2H), 2.03-1.92 (m, 2H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.63 (m, 1H), 1.58 and 1.53 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.49 and 1.47 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.48-1.46 (m, 1H), 1.47 and 1.45 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.39-1.26 (m, 2H), 1.15 and 1.12 (2 d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H combined), 1.09 (s, 9H), 1.08 and 1.07 (2 d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H combined), 0.86 and 0.85 (2 d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H combined); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.85-7.82 (m, 4H), 7.35 (dd, J = 15.3, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26-7.22 (m, 6H), 6.78 and 6.77 (2 d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H combined), 6.28 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.96 and 5.93 (2 d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H combined), 5.94 and 5.90 (2 d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H combined), 5.81-5.77 (m, 2H), 5.63 (br d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.57 and 5.56 (2 d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H combined), 5.29 and 5.28 (2 dd, J = 15.3, 9.7 Hz, 1H combined), 5.30 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 4.10 and 3.87 (2 m, 1H combined), 4.02 and 3.96 (2 dd, J = 10.6, 4.5 Hz, 1H combined), 3.84 (m, 1H), 3.11 (br d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.00 and 2.99 (2 s, 3H combined), 2.71-2.61 (m, 2H), 2.31-2.21 (m, 2H), 1.96-1.89 (m, 1H), 1.87 (s, 3H), 1.84 (m, 1H), 1.72 and 1.69 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.68 and 1.65 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.64 (m, 1H overlapped), 1.50 and 1.45 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.44 (m, 1H overlapped), 1.22 (s, 9H), 1.20-1.16 (2 d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H combined), 0.98 (s, 3H), 0.92 and 0.91 (2 d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H combined), 0.64 and 0.63 (2 d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H combined); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 167.3, 151.9, 151.5, 142.5, 141.8, 138.2, 135.6, 135.4, 135.3, 134.2, 134.1, 132.7, 132.6, 132.2, 130.8, 129.7, 129.6, 129.5, 127.61, 127.57, 125.80, 125.77, 125.32, 125.28, 122.2, 122.0, 92.7, 92.3, 79.6, 79.0, 77.7, 77.2, 77.0 (overlapping w/chloroform), 75.7, 75.6, 71.5, 55.7, 54.5, 43.3, 41.6, 41.52, 41.48, 41.47, 41.4, 41.3, 38.6, 37.1, 34.3, 34.1, 30.81, 30.77, 30.0, 29.9, 28.6, 28.5, 28.2, 27.3, 27.0, 24.7, 23.5, 21.1, 19.3, 17.6, 17.5, 13.7, 13.0, 11.99, 11.97, 9.3, 9.2; IR (neat) 2929, 1695, 1388, 1258, 1110, 1003, 867, 820 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z for C57H79NO7SiNa [M + Na]+ calcd 940.5518, found 940.5517. [Note: compound 54 exhibited coalescence of 1H NMR signals at 50 ºC in C6D6. See Supporting Information (2)]

Synthesis of (+)-Superstolide A from Cycloadduct 54

To a 0 ºC solution of 54 (20.0 mg, 0.022 mmol) in THF (1 mL) was added TBAF (0.13 mL of a 0.5 M solution in THF, freshly prepared, 0.066 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h, diluted with EtOAc (3 mL) and poured into water (2 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 3 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated. Purification of the crude product by flash chromatography (30–50% EtOAc-hexanes) afforded the C(13)-alcohol (designated SI-11, 11 mg, 0.016 mmol, 73%) as a white foam: [α]25 D = +76.5º (c 1.00, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.08 and 7.07 (2 dd, J = 15.5, 10.5 Hz, 1 H combined), 6.67 and 6.65 (2 d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H combined), 6.11 (2 d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H combined), 5.89 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.75 and 5.74 (2 d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H combined), 5.67 (2 d, 2H overlapped), 5.54 (dt, J = 10.2, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 5.39 and 5.38 (2 dd, J = 15.3, 9.7 Hz, 1H combined), 4.97 and 4.96 (2 d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H combined), 3.95 and 3.78 (qd and m, J = 6.4, 4.9 Hz, 1H combined), 3.88 and 3.85 (2 dd, J = 10.5, 4.6 Hz, 1H combined), 3.82-3.75 (m, 1H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 3.12 (br d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (m, 1 H), 2.74 (br s, 1H), 2.44 (m, 1H), 2.17 (br d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1H), 1.88 (s, 3H), 1.78 (s, 3H), 1.77 (m, 1H), 1.58 and 1.53 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.50 and 1.47 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.47 and 1.45 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.44-1.40 (m, 2H), 1.25 (m, 1H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.12 and 1.09 (2 d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H combined), 1.08 and 1.07 (2 d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H combined), 0.87 and 0.85 (2 d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H combined); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 167.3, 151.9, 151.5, 142.3, 141.8, 138.1, 135.32, 135.28, 132.9, 132.8, 132.0, 131.0, 130.25, 130.23, 126.04, 126.01, 125.45, 125.43, 121.3, 120.9, 92.7, 92.3, 79.7, 79.0, 77.8, 77.1, 76.9, 75.70, 75.66, 70.3, 55.9, 54.51, 54.50, 43.4, 41.9, 41.8, 41.5, 41.4, 41.3, 38.6, 36.73, 36.69, 34.2, 34.0, 31.0, 30.9, 30.2, 30.1, 28.6, 28.5, 28.2, 27.3, 24.7, 23.5, 21.1, 17.55, 17.52, 13.7, 13.0, 12.02, 12.00, 9.3, 9.2; IR (neat) 3460, 2977, 2934, 2873, 1737, 1698, 1456, 1392, 1375, 1253, 1176, 1113, 1052, 1003, 738 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z for C41H61NO7Na [M + Na]+ calcd 702.4340, found 702.4405.

To a solution of the C(13)-alcohol (SI-11, 11.0 mg, 0.016 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL) was added trichloroacetyl isocyanate (6.0 μL, 0.05 mmol). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 30 min and then loaded directly onto neutral Al2O3 and allowed to stand for 4 h. The product was flushed from the neutral Al2O3 with EtOAc and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. Purification of the crude product by flash chromatography (30–50% EtOAc/hexanes) afforded the C(13)-carbamate (SI-12, 9.0 mg, 0.012 mmol, 76%) as a white foam: [α]25 D = +64.9º (c 0.74, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.08 and 7.06 (2 dd, J = 15.3, 10.6 Hz, 1H combined), 6.67 and 6.65 (2 d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H combined), 6.11 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 5.90 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 5.75 and 5.74 (2 d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H combined), 5.66 (m, 3H), 5.53 (dt, J = 10.3, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 5.39 and 5.38 (2 dd, J = 15.4, 9.7 Hz, 1H combined), 4.97 and 4.96 (2 d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H combined), 4.76 (dt, J = 12.5, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (br s, 2H), 3.96 and 3.79 (2 m, 1H combined), 3.88 and 3.86 (2 dd, J = 10.7, 4.5 Hz, 1H combined), 3.34 (s, 3H), 3.14-3.06 (m, 2H), 2.87 (br s, 1H), 2.44 (m, 1H), 2.25 (br d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1 H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.79 (s, 3H), 1.58 and 1.53 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.50 and 1.47 (2 s, 3H combined), 1.50-1.40 (m, 2H overlapped), 1.47 and 1.45 (2 s, 9H combined), 1.30 (m, 1H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.12 and 1.09 (2 d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H combined), 1.08 and 1.07 (2 d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H combined), 0.87 and 0.85 (2 d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 167.3, 156.0, 151.9, 151.5, 142.0, 141.8, 138.2, 135.3, 135.2, 133.0, 132.9, 131.8, 131.1, 130.51, 130.50, 126.13, 126.09, 125.51, 125.47, 121.3, 121.1, 92.7, 92.3, 79.7, 79.0, 77.5, 77.1, 77.0 (overlapping w/chloroform), 75.7, 75.6, 72.9, 56.0, 54.5, 43.2, 41.53, 41.51, 41.44, 41.39, 41.3, 36.1, 34.3, 34.0, 33.6, 31.1, 31.0, 30.2, 30.1, 28.6, 28.5, 28.2, 27.3, 24.7, 23.5, 21.1, 17.55, 17.51, 13.7, 13.0, 12.03, 12.01, 9.3, 9.2; IR (neat) 3422, 2977, 1681, 1673, 1632, 1391, 1257, 1112, 1054, 1003, 867 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z for C42H62N2O8Na [M + Na]+ calcd 745.4398, found 745.4439.

To a solution of carbamate SI-12 (6 mg, 0.008 mmol) in wet CH2Cl2 (20 μL of water in 0.80 mL of CH2Cl2) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.4 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature and then concentrated in vacuo. Toluene (1 mL) was added and the solution was concentrated (x 3, to remove all trifluoroacetic acid). The residue was diluted in THF (0.8 mL) and triethylamine (12 μL, 0.083 mmol) was added followed by acetic anhydride (3 μL, 0.03 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature and then concentrated. Purification of the crude product by flash chromatography (50–100% EtOAc/hexanes) afforded totally synthetic (+)-superstolide A (1) (4 mg, 0.006 mmol, 75%) as an amorphous white solid: [α]25 D = +84.0 º (c 0.40, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.21 (dd, J = 15.2, 11.0 Hz, 1H, H-3), 6.87 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H, H-6), 6.29 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, H-20), 6.23 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.91 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H, H-4), 5.79 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H, H-18), 5.70 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.68 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-16), 5.60 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H, H- 7), 5.52 (dt, J = 10.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H, H-15), 5.32 (dd, J = 15.2, 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-21), 4.79 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H, H-23), 4.77 (m, 1H, H-13), 4.63 (br s, 2H, NH2), 4.19 (m, 1H, H-26), 3.35 (s, 3H, MeO), 3.33 (br s, 1H, OH-25, overlapped), 3.16 (dd, J = 10.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-25), 3.10 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.89 (br s, 1H, H-14), 2.71 (m, 1H, H-22), 2.24 (br d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H, H-12), 1.97 (s, 3H, Me-28), 1.92 (s, 3H, Me-29), 1.80 (m, 2H, H-10, H-24), 1.77 (s, 3H, Me-32), 1.48 (m, 1H, H-9), 1.45 (m, 1H, H-10), 1.30 (m, 1H, H-12), 1.15 (s, 3H, Me-30), 1.08 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, Me-33), 1.05 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, Me-35), 0.90 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Me-34); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.7, 169.0, 156.1, 142.7, 142.6, 139.3, 137.1, 133.1, 132.4, 130.2, 129.4, 125.8, 125.5, 121.3, 120.3, 77.0 (2C overlapping w/chloroform), 73.1, 72.8, 56.1, 45.5, 42.9, 41.8, 40.9, 40.4, 37.6, 36.0, 33.7, 31.3, 30.8, 23.5, 20.7, 18.0, 12.6, 12.0, 8.8; IR (neat) 3434, 3351, 2961, 2927, 1716, 1692, 1528, 1451, 1376, 1331, 1261, 1100, 1059, 981 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z for C36H52N2O7Na [M + Na]+ calcd 647.3667, found 647.3666.

When making a detailed comparison of the carbon spectrum of the synthetic sample of (+)-superstolide A with that from the isolation paper, we noticed that the peak for the ester carbon of the macrolactone in our spectrum was significantly smaller than that in the isolation paper. Numerous experiments (increased number of scans, increased relaxation time, increased temperature) were tried in order to minimize this difference, but without success. However, from the proton spectrum it was clear that the isolation sample had a much more water present than the synthetic sample. Remarkably, addition of 1 μL of water to the NMR sample of synthetic (+)-superstolide A provided a 13C NMR spectrum that perfectly matched the 13C NMR spectrum available in the literature for natural superstolide A.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 1.

Superstolides A and B

Scheme 5.

IMDA of Pentaenal 5

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM026782) is gratefully acknowledged. We also acknowledge Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain, for a postdoctoral fellowship to M. T.

References

- 1.D’Auria MV, Debitus C, Paloma LG, Minale L, Zampella A. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:6658. [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Auria MV, Paloma LG, Minale L, Zampella A, Debitus C. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:1595. doi: 10.1021/np50113a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zampella A, D’Auria MV. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:1543. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu W, Zhang Y, Jin Z. Org Lett. 2001;3:1447. doi: 10.1021/ol0100273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solsona JG, Romea P, Urpi F. Org Lett. 2003;5:4681. doi: 10.1021/ol035874f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson I, Mackay AC. Synlett. 2004:1359. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall JA, Mulhearn JJ. Org Lett. 2005;7:1593. doi: 10.1021/ol050289v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Roush WR, Hertel L, Schnaderbeck MJ, Yakelis NA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4885. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yakelis NA, Roush WR. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3838. doi: 10.1021/jo0341012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roush WR, Champoux JA, Peterson BC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hua Z, Yu W, Su M, Jin Z. Org Lett. 2005;7:1939. doi: 10.1021/ol050339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tortosa M, Yakelis NA, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2722. doi: 10.1021/ja710238h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stocking EM, Williams RM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3078. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oikawa H, Tokiwano T. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:321. doi: 10.1039/b305068h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Takao K-i, Munakata R, Tadano K. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4779. doi: 10.1021/cr040632u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Deslongchamps P. Aldrichimica Acta. 1991;24:43. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roush WR. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, editor. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1991. pp. 513–550. [Google Scholar]; (d) Craig D. Chem Soc Rev. 1987;16:187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roush WR, Koyama K, Curtin ML, Moriarty KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7502. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Mergott DJ, Frank SA, Roush WR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401247101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Winbush SM, Mergot DJ, Roush WR. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1818. doi: 10.1021/jo7024515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeckman RK, Jr, Flann CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5035. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Review of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions in total synthesis: Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4442. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500368.

- 19.Smith AB, III, Chen SS-Y, Nelson FC, Reichert JM, Salvatore BA. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10935. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Still WC, Gennari C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:4405. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh JR, Doering WvE. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5505. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takai K, Nitta K, Utimoto K. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7408. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takai K, Shinomiya N, Kaihara H, Yoshida N, Moriwake T. Synlett. 1995:963. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans DA, Gage JR, Leighton JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9434. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stille JK, Groh BL. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:813. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markó IE, Murphy F, Dolan S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:2507. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMDA cyclization of 5 was attempted in toluene at 70–80 ºC but 1H NMR analysis showed lower conversion and decomposition of 5.

- 28.Wuts PG, Thompson PA. J Organometallic Chem. 1982;234:137. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominguez B, Pazos Y, de Lera AR. J Org Chem. 2000;65:5917. doi: 10.1021/jo9917588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cushman M, Casimiro-Garcia A, Hejchman E, Ruell JA, Huang M, Schaeffer CA, Williamson K, Rice WG, Buckheit RWJ. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2076. doi: 10.1021/jm9800595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compound 25 could not be fully characterized due to the small quantities obtained from these experiments but 1H NMR spectra showed a TBS ether on C(23).

- 32.(a) Seyferth D, Marmor RS, Hilbert P. J Org Chem. 1971;36:1379. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gilbert JC, Weerasooriya U. J Org Chem. 1982;47:1837. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohira S, Okai K, Moritani T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1992:721. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corey EJ, Fuchs PL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972;13:3769. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Coleman RS, Walczak MC. Org Lett. 2005;7:2289. doi: 10.1021/ol050768u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coleman RS, Lu X. Chem Commun. 2006:423. doi: 10.1039/b514233d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gröbel BT, Seebach D. Chem Ber. 1977;110:852. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matteson DS, Moody RJ. Organometallics. 1982;1:20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buchwald SL, LaMaire SJ, Nielsen RB, Watson BT, King SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:3895. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalinin AV, Scherer S, Snieckus V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fell SCM, Harbridge JB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4227. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7277. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans DA, Black WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:4497. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farina V, Krishnan B. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9585. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bimetallic linchpin 36 provided an alternative route to access IMDA precursors analogous to 22 and 5 for the synthesis of IMDA adduct 26 (See Supporting Information). This sequence was more reliable than the previously described in schemes 3 and 4.

- 45.Frank SA, Chen H, Kunz RK, Schnaderbeck MJ, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2000;2:2691. doi: 10.1021/ol0062446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otera J, Danoh N, Nozaki H. J Org Chem. 1991;56:5307. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laganis ED, Chenard BL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:5831. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hikota M, Tone H, Horita K, Yonemitsu O. J Org Chem. 1990;55:7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiina I, Kubota M, Ibuka R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:7535. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheidt KA, Chen H, Follows BC, Chemler SR, Coffey DS, Roush WR. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6436. [Google Scholar]

- 52.For recent examples of Suzuki macrocyclization reactions: Jia Y, Bois-Choussy M, Zhu J. Org Lett. 2007;9:2401. doi: 10.1021/ol070889p.Wu B, Liu Q, Sulikowski GA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6673. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461469.Molander GA, Dehmel F. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10313. doi: 10.1021/ja047190o.

- 53.Kocovsky P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:5521. [Google Scholar]

- 54.The spectroscopic and physical properties (e.g., 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR, mass spectrum and/or C, H analysis) of all new compounds were fully consistent with the assigned structures. Yields refer to chromatographically and spectroscopically homogeneous materials (unless noted otherwise). Experimental procedures and tabulated spectroscopic data for other new compounds are provided in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.