Abstract

In recent years, the EVB has become a widely used tool in the QM/MM modeling of reactions in condensed phases and in biological systems, with ever increasing popularity. However, despite the fact that its power and validity have been repeatedly established since 1980, a recent work (Valero et al., J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 5 (2009), 1) has strongly criticized this approach, while overlooking the fact that one of the authors is effectively using it themselves for both gas-phase and solution studies. Here, we have responded to the most serious unjustified assertions of that paper, covering both the more problematic aspects of their work as well as the more complex scientific aspects. Additionally, we have demonstrated that the poor EVB results shown in Valero et al. which where presented as verification of the unreliability of the EVB model were in fact obtained by the use of incorrect parameters.

Keywords: EVB, Dehalogenase, MOVB, Energy Surface

In recent years, the EVB has become a widely used tool in the QM/MM modeling of reactions in condensed phases and in biological systems, and, despite initial skepticism, its power and validity have been repeatedly established since 1980. In some respects, the widespread adoption of the EVB has been the best proof of its validity (see Ref. 1 for further details). Unfortunately, a recent work2 by Truhlar, Gao and their coworkers has strongly criticized the EVB approach, while overlooking the fact that one of the authors is using an effectively identical adaptation himself for both gas phase3 and solution studies4. Here, we provide clarification of the most problematic claims of the paper, and the implications thereof. We will start by first establishing the ethical issues and then move on to the more complex scientific aspects.

I. The Main Criticism of the EVB Approach is Apparently Incorrect

Ref. 2 is a lengthy work, which is presented as “Perspective” on diabatic models of chemical reactivity. On the surface, this work presents six different two-state approaches, one of which is the EVB. However, a close examination of this work will very quickly establish that its main aim is to undermine the validity of the EVB approach. We base this belief not on the fact that the EVB is repeatedly illustrated as comparing unfavorably to other approaches presented in the work, which in a fair comparison would be a justifiable and legitimate comparison to make, but rather on the fact that the unfavorable performance of the EVB is illustrated by a combination of very serious incorrect allegations. The problematic allegations can be grouped into 6 main categories: (i) Trying to reproduce our EVB gas phase surface while using incorrect parameters, which unsurprisingly resulted in an incorrect surface that has nothing to do with the actual EVB surface which was done without trying to use the relevant computer program in order to really examine the validity of their accusation (and then presenting the resulting incorrect surface as proof of the shortcomings of the EVB approach); (ii) claiming that the authors could not reproduce the EVB solution results, without actually having ever demonstrated any experience with EVB free energy calculations; (iii) stating that the EVB cannot calculate “detailed rate quantities such as kinetic isotope effects that require an accurate treatment of the potential energy surface, zero-point energy (ZPE), and quantum mechanical tunneling” whereas there are examples of the accurate calculation of all these properties in the literature, which the authors neglect to cite. This issue will be discussed in greater detail below, with examples; (iv) telling the readers that the EVB has never been parameterized to the ab initio surface, where this was done repeatedly (starting already in 1988), and has been clarified in our papers in addressing the authors' allegations; (v) trying to imply that EVB approaches that are parameterize to reproduce ab initio surfaces, including the authors' version (the so called MCMM model3-5, which is basically identical to the EVB as we have discussed in detail elsewhere1,6), are significantly different to our original EVB approach which does the same thing, and (vi) attacking the EVB usage of orthogonalized diabatic states and solvent independent off-diagonal elements, while ignoring the fact that a CDFT study7 has established the validity of such an approximation. All of this comes at a time when the lead author is presenting a “novel” approach for modeling chemical reactivity, which he refers to as the electrostatically embedded multiconfigurational molecular mechanics (MCMM) approach4, and which closer examination will demonstrate is for all intents and purposes identical to the EVB approach. The analogy between these methods was already illustrated in our recent Centennial Article for J. Phys. Chem.8 and will be discussed further below.

I.1. The EVB has been Parameterized on Ab Initio Surfaces for a Long Time, and thus the MCMM Versions do not Present Any Fundamental Change

We would first like to focus on one key point: Ref. 2 singles out our EVB approach from more recent EVB adaptations by repeating the claim that our EVB approach has presumably never parameterized the off-diagonal elements (i.e. the Hij term) by fitting them to ab initio calculations, and thus that this creates a major difference between our EVB and the MCMM adaptation of the EVB, as well as other EVB versions. As we have already repeatedly clarified since the first time that this allegation was made9, this is simply incorrect. The EVB was parameterized to reproduce ab initio results starting as early as 198810 (see Fig. 1 in this paper), even before the important work of Chang and Miller11, and this was done professionally in very careful studies12,13 long before the gas phase adaptation of the MCMM approach. This was done even earlier14 by Miller's approach11, and by approaches that parameterized the whole surface and not only the reactants and products12 (see Fig. 1). We have even reported EVB parameterization to ab initio results for the challenging case of the autodissociation of water in water15 and other studies13,16. Not mentioning this fact in Ref. 2 gives the reader a distorted view of the EVB approach. The main point is that the authors argue that there is a difference where there is none, and, as we will see below, the lead author uses the same EVB approach (repackaged with a different name), while simultaneously criticizing it.

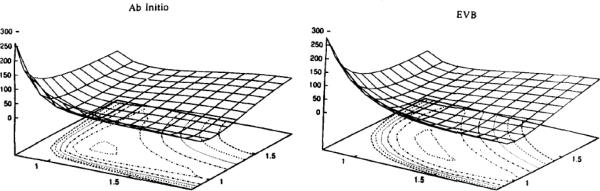

Figure 1.

Gas phase potential surfaces for proton transfer in the [HOHOH]- ion, obtained using both ab initio (MP2/6-31G**, left) and EVB (right) approaches. All results are given in kcal/mol, relative to the R00 minimum. This figure was originally presented in Ref. 12.

I.2 The Authors Present a Faulty EVB Surface as Evidence of Problems with the EVB Approach

One of the key criticism of the EVB approach presented in Ref. 2 focuses on the attempt to generate the corresponding gas phase surface without any serious effort to validate the similarity between the models used by the authors of Ref. 2 and the one that was used in Ref. 17. Such a validation should start by using the same program (which is readily available on request, but was not asked for) to demonstrate that one is actually able to reproduce available results, or by trying to reproduce the reported solution profile (which would require familiarity with the corresponding mapping), before moving on to one's own code. This is crucial, in particular when one is trying to discredit a given model without consulting the main author. As expected, we find major problems with the presumed reproduction of our gas phase EVB surface.

More specifically, we have evaluated the adiabatic potential energy (rather than the usual free energy) surface using our own MOLARIS18 software package to generate two EVB potential energy surfaces, using two different gas-phase shifts (α=-23.0 (incorrect) and +23.4 (correct)). The corresponding surfaces are shown in Figs. 2a and b respectively. From Fig. 2a, it can be seen that when we use an incorrect gas phase shift without thorough mapping, we obtain a very bad EVB surface that is qualitatively very similar to that presented in Ref. 2. However, when using the correct gas-phase shift (which is incidentally the one published in the supporting information of not only our Ref. 17, but also of that of Ref. 2) and careful mapping (i.e. examining each point to ensure that the true lowest energy free energy surface is obtained and that we have not crossed over into a different slice of the full multidimensional free energy surface), we obtained physically meaningful. This point is discussed in much more detail in Section II.4. To illustrate the seriousness of this error even further we would like to point out to the reader that the system under scrutiny is an exceedingly simple system, and computers have come a long way since the EVB approach was first introduced. The calculations required to generate Fig. 2 were run on Dell Quad-Core Intel® Xeon® dual-processor nodes on the USC HPCC cluster, and the entire process including setting up time took ~2 hours. To repeat the calculations using different gas-phase shifts for validation would not have been an extensive effort, and we are puzzled as to why the authors did not try this (that is, we find the thoroughness of their efforts to reproduce our results questionable due to the fact that these are simple calculations, and if they were able to generate the incorrect surface suggesting they were not very far from generating the correct surface merely by altering the gas-phase shift).

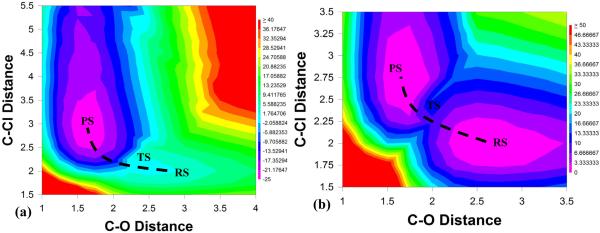

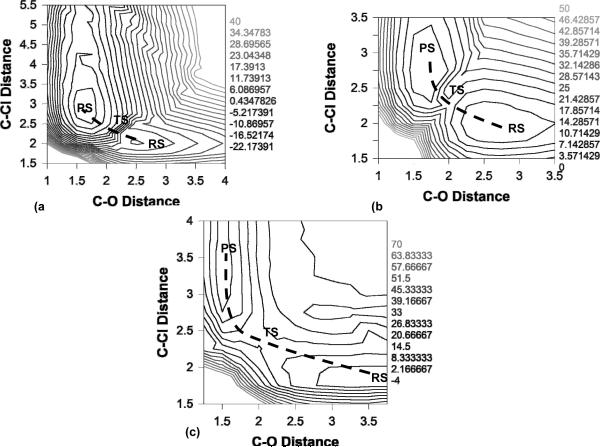

Figure 2.

Contour plot of the ground-state adiabatic potential surfaces obtained by (a) EVB with a gas-phase shift of -23.0, (b) EVB with a gas-phase shift of +23.4.

I.3. Overview of the Other Key Problems

Here, we will address the more specific contentious points in Ref. 2 in detail:

It is stated that “the EVB model is not well suited for computing detailed rate quantities such as kinetic isotope effects that require an accurate treatment of the potential energy surface, the zero-point energy (ZPE) and quantum mechanical tunneling”. Our EVB was never found to be insufficient for calculations of isotope effects, and there is not one example in the literature that shows this to be the case. In fact, as was shown by countless studies (by e.g. Warshel19,20, Åqvist21,22, Hammes-Schiffer23,…), the EVB is one of the most effective ways of reproducing isotope effects, in clear contrast to the misinformation being reported.

Similarly, Ref. 2 focuses on casting doubts about the accuracy of EVB calculations of reaction free energies, while neglecting to mention the 2006 study of the dehalogenase (DhlA) reaction24, which is the most direct examination of the EVB free energy surface by ab initio approaches. No other quantitative ab initio QM/MM free energy calculations of the dehalogenase system have been reported by any group, including by any of the authors of Ref. 2 (see more below).

Subsequently, Ref. 2 claims that the EVB keeps diabatic charges that do not change along the reaction coordinate and that “although in principle it is possible to make the atomic partial charges in EVB-type models dependent on molecular structure, it is rarely done, and such a procedure is laborious for chemical reactions”. Firstly, this is a distortion of facts, since many EVB studies, including the paper that introduced the EVB have considered the polarization of the diabatic state.(Eq. 29 in Ref. 25). The same was done in our 1988 papers (see Eq. 11 in Ref. 10 and Eq. 7 in Ref. 26, and even in our book 27, where Chapter 3 describes gas phase surfaces for SN2 reactions with polarization of the diabatic states. In fact, some of our treatments (see e.g. Eq. 7 of Ref. 26) are more consistent than any of the treatments presented in Ref. 2 (see Section II.3) Secondly, comparing the results with and without polarized diabatic states has established that using fixed charges it is a very good approximation for charge transfer reactions. This was established by examining the behavior of the solute charges in the gas phase and in solution, while calibrating the off-diagonal element to reproduce the change of the adiabatic charges along the reaction coordinate. Criticizing an approximation without examining its effect is not productive, especially when criticizing those who have invested major effort into exploring this point long ago.

In a seemingly thorough analysis of solvated EVB, we are told that including solvation effects in the diagonal and calibrating on the isolated fragment in solution “are mutually incompatible”. However, the isolated fragments have the same solvation as the diabatic states, since the mixing term has no effect when the fragments are at infinite separation. It should also be pointed out that the diatomic-in-molecule method which was brought up by the authors, and the EVB have very different physics. The EVB diabatic state at infinite separation is the isolated fragment, and it is identical to the adiabatic state. Overlooking this issue is a cause for concern. This problem is compounded by not pointing out the fact that the embedded MCMM also includes the solvation effect in the diagonal element. Of course, the EVB puts the solvent into the diagonal Hamiltonian. Trying to solvate the adiabatic charges rather than the diabatic states leads to bad physics, particularly in the case of SN1 type and proton transfer reactions (the problems with SN1 reactions were already clarified in the 1988 paper). Thus, the EVB calibration has little to do with the consistent incorporation of the solvent in the diagonal elements. In fact, when the EVB is calibrated at configurations that are not at infinite separation, we frequently demand that the adiabatic charges and energies in solution will be equal to the adiabatic solvated ab initio.

We are further told that using an environmentally independent H12 is a source of major error. This would have possibly been a reasonable criticism if: a) the authors were not aware of the recent CDFT calculations7 that proved that the EVB approximation of a phase-independent H12 is actually valid (see below); (b) the authors had any estimate of the proposed error, and (c) if the authors of Ref. 2 were not unknowingly themselves reproducing an H12 that is basically environmentally independent H12 (see the discussion in Ref. 8 and below). Furthermore, one would have expected a realization that H12 is different for different representations (i.e. with and without overlap). Obviously, we have explained this issue clearly since 198810. Finally, the authors of Ref. 2 proceed to discuss the reorganization energy, while criticizing how the EVB works, without having any apparent experience in the computation of this property (see below).

Whether the gas-phase EVB gives the exact gas-phase ab initio result or not is another problematic question (in addition to the fact, considered above, that our gas phase surface was completely misrepresented). That is, there exists an extremely careful study (that should be known to the authors28), where the EVB is used as a reference for the ab initio calculations. This work demonstrates the excellent and accurate performance of the EVB in solutions and enzymes (no such demonstration was ever reported by the authors). The surface presented in Ref. 28 should have been discussed for the sake of transparency.

The authors of Ref. 2 include the overlap integral, S12, in their specification of H12, and we are told that neglecting the overlap is an additional source of error. This statement is problematic, since the authors cannot actually judge or establish any error, as this has to be done by comparison to ab initio calculations in solution, which were never done by the authors (but has been done in our FDFT study). Moreover, talking about “errors” due to neglecting the overlap is misleading, as this is a formally orthogonalized model without errors (since the selection of the diabatic states is the way the model is defined, and for each diabatic treatment we can have a unique H12 that reproduces the exact adiabatic surface). Different adiabatic states require different off-diagonal terms, and a model without overlap (which is what is done in the so called embedded MCMM approach discussed below) has different off-diagonal terms than the one with overlap. Obviously such different models should be very different from the H12 with overlap. More specifically, in the bottom right paragraph of pg. 7, the authors state that “it would be meaningless to specify without also specifying S12 ”. This is a strange assertion in view of the adoption of this same approach in their own MCMM approach. Moreover the strength of the EVB stems from not using the wave function and overlap but rather using a unique relationship (Eq.1 below) between the diabatic and adiabatic states. We have known since 198025 that the overlap between the VB states presents a major difficulty in the practical implementation of VB type approaches and thus chose the EVB strategy. Now, the authors still consider the EVB wrong since they believe its H12 is very different to that obtained by the MOVB orthogonalization. However, the H12 obtained by the Truhlar QM approach of Ref. 2 is also extremely different from that of the MOVB coupling (see Fig 9 of Ref. 2). More revealing is the fact that the presumably wrong EVB H12 is not much different from that obtained by Truhlar's MCMM treatment4, where both are almost constant.

It is stated that calculations using the EVB surface “have been unable to reproduce the free energy of activation obtained by molecular dynamics simulations (24.9 kcal/mol). These findings cast doubts on the reported EVB results and suggest that a careful parameterization of the gas-phase reaction might have been useful in order to obtain more meaningful results for the condensed-phase reaction by the EVB method.” This is extremely problematic, particularly considering that the authors have not tried to actually perform EVB free energy calculations in any of their published works, yet venture to claim that such calculations are wrong. More detailed discussion of this problematic conduct will be given below.

The calculated EVB solvation energies reported by the authors in Table 4 of their paper have little to do with the correct EVB solvation energies, and, more disturbingly, have no similarity to the values reported in our paper29, or to the values expected form decent solvation models. Thus, the results reported in Table 4 suggesting that our results are wrong should have been sufficient warning that an incorrect model was used. More specifically, to claim that the EVB gives more solvation in the TS that in the ground state in SN2 reaction, whereas neither we nor any other EVB user ever obtained this in any EVB calculations is a cause for concern. Though this is not the only cause for concern in this work, we believe that the discussion and analysis of the solvation results of our EVB is one of the most misleading parts of the paper. Apparently, the authors also overlook our footnote in Ref. 29, and conclude that a negative barrier must be present in the gas phase of our work, which is simply factually incorrect. Subsequently, they speculate on the reason why the solvation energies that were attributed to us are different to those we reported, without trying to use our program (which is readily available on request to any interested party and would have been to the authors of Ref. 2 had they ever asked for it). We are then told that our reported solution results could not be reproduced because our gas phase EVB is wrong, which is very concerning - regardless of our gas phase surface (which is apparently correct, see Fig. 2). That is, we reported our solution results and failing to reproduce it means that something is wrong in the approach used to reproduce our solution results. In case the reader finds this point unclear, let us repeat that the issue is what our results actually are, and not what the authors of Ref. 2 think that our results are.

Giving so much importance to the failure to reproduce our free energy surfaces in solution by a treatment that does not involve proper EVB mapping is puzzling. The authors in their 2003 Biochemistry paper30 implied that the EVB energy gap mapping (which is very widely used, see e.g. Refs. 23,31-34) is ineffective, without having accurately calculated it themselves. This issue has been discussed in Ref. 35 and further elaborated below.

We are told it is possible to unify treatments based on different choices of the reaction coordinate (i.e. a valence-coordinate reaction path or a collective reaction coordinate) by calculating not only the transition state theory rate constant but also the transmission coefficient. However, just above this, the authors themselves assert that in their present work, they are “examining the EVB diabatic curves in a different context, using a geometrical reaction coordinate different from the one (an energy-gap coordinate) for which they were originally parameterized along. This basically puts the authors in a precarious position when it comes to commenting on the efficiency of the EVB in evaluating transmission factors as they are not using the original approach. Firstly, not checking the EVB with the energy gap because, presumably, a quantitatively correct atomistic description in term of “all relevant atomic coordinates” is crucial for evaluating transmission factors is strange. Furthermore, it is important to note that the assertion about the transmission factor (i.e. that evaluating this property is essential for unifying different approaches) is misleading, as it carries a veiled suggestion that only the authors knew how to do so, while forgetting to tell the reader that countless works (including ours19 as well as that of Hammes-Schiffer31 and Karplus36) that actually have used the EVB surface and/or the EVB energy gap gave exactly the same or better results for the transmission factor for different proteins, including the same system19 that they venture to mention here.

The authors then argue that the MOVB approach gives different solute-solvent interaction energies than the EVB, and thus the EVB is presumably problematic. However, as was demonstrated in our 2006 paper (see Fig. 3 of this work, which was originally presented in Ref. 24), the EVB gives rigorous solute-solvent interaction energies, that are the same as the ab initio results. No such study was ever reported by the MOVB. More specifically, the authors state that by using MOVB, they only find a weak change in solute-solvent interactions along the reaction coordinate in contrast to our 1988 paper10. Firstly, they overlook the fact that the Ref. 10 gave time dependence along the correct downhill path and not along some arbitrary reaction coordinate, and, of course we are not aware of any dynamical MOVB study that is able to produce such time dependence, or in fact any time dependence of the charge solvent interaction. In fact, our study is consistent with the experimental trend of solvation dynamics. We are also not aware of any proper study of the variation of the solute-solvent interaction, which requires looking at the adiabatic charges and the solvent, which we have done in comparing the EVB to ab initio QM/MM. Finally, it is unjustified to criticize the work of Ref. 10 with regards to its solute-solvent interaction, when it presented an accurate ab initio gas phase potential and an accurate free energy in solution, and thus obviously the correct interaction with the solvent.

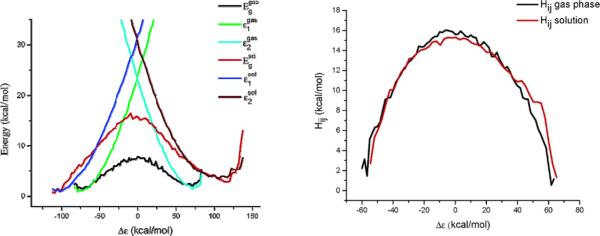

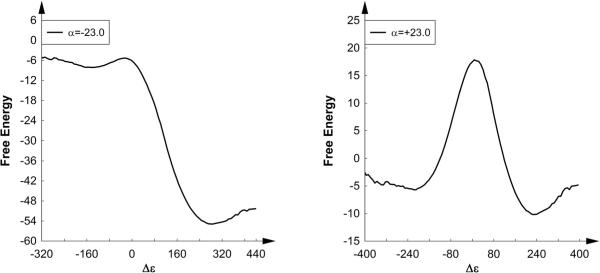

Figure 3.

(left) Diabatic and adiabatic FDFT energy profiles for the reaction, Cl- + CH3Cl → ClCH3 + Cl-, in the gas phase and in solution, where the reaction coordinate is defined as the energy difference between the diabatic surfaces, Δε = ε1 - ε2. (right) Plot of the Hij of the reaction, Cl- + CH3Cl → ClCH3 + Cl-, both in the gas phase and in solution. The data are obtained from the diabatic and the adiabatic curves of Figure 1, using . These figures were originally presented in Ref. 7.

We are told that in the future (after presumably validating the gas phase surfaces), the VB method will be effective in studies of enzymes. This unfortunate statement (that overlooks all previous quantitative validation of the EVB in solutions and enzymes, as is shown in for instance Fig 3) will be addressed in the concluding remarks.

In addition to the above concerns, it is worrying to see that the paper tries to imply that the MOVB (or perhaps some other approach) is the best way to treat enzymatic reactions in general and the DhlA reaction in particular when we have yet to see any single condensed phase MOVB study of DhlA, whereas the EVB has been used as the basis for what is, to date, the most rigorous ab initio QM/MM-free energy perturbation study of an enzymatic reaction that has been performed on DhlA24 (see below for further discussion). Thus, not only has the EVB been shown to be much more effective and quantitative than the MOVB, but, from the implications of Ref. 2, it would seem that the authors are now trying to use the EVB under a new name for studies of enzymatic reactions.

II. Misunderstandings of Scientific Issues

Although Ref. 2 is presented as a perspective on diabatic representations, in reality it is mainly a repeated attack on the EVB approach. The major problem is that most of the attacks are unjustified, as they are simply scientifically incorrect. Here, we will address the main misunderstandings about the nature of the diabatic representation. We will start with the general points, and then move to more detailed discussion.

II.1 The Justification for the EVB Diabatic Representation

The work of Ref. 2 focuses on criticizing the use of the EVB orthogonal surfaces as well as the use of a solvent independent H12. We will not continue to point out that this is the approach used in the embedded MCMM, and by any of the EVB workers, but will rather first clarify that strange dismissal of the orthogonal diabatic representation is based on the perspective that since the MOVB and other VB approaches have a very large (and complex) overlap effect, it must be included in all diabatic treatments. This view is fundamentally flawed, as the diabatic representation is not a “reality”, but rather a powerful mathematical tool, and the best tool is of course the one that produces the most accurate adiabatic QM/MM free energy surface. Here we are not aware of any careful study by the MOVB that has done so, whereas our CDFT studies37,38 (which were overlooked in Ref. 2) involved an ab initio constrained DFT (CDFT) diabatic treatment of an SN2 reaction as well as proton transfer reactions (see also recent related studies such as that in Ref. 39). The CDFT approach constructed two diabatic states with formal Löwdin orthogonality, as is done in all EVB studies. These surfaces (ε1 and ε2) are constructed by mixing the effective off diagonal terms, and the ground state energy (Eg) is obtained as the lowest eigenvalue of the 2×x2 EVB Hamiltonian. Using both the diabatic surfaces and the adiabatic surface obtained by treating the whole reaction system with a regular DFT treatment will give us per definition the rigorous off-diagonal element by the relationship below:

| (1) |

This relationship is shown schematically in Fig. 3. The study of Ref. 7 established that the EVB approximation of a solvent independent H12 is an excellent one. However, no such study has been reported by the MOVB or was ever explored in any successful use of this method in condensed phase studies. Thus, we have demonstrated that using formally orthogonal diabatic surfaces (were the solvation of each diabatic state is included in the diabatic energies) is an excellent approximation since it reproduces the correct solvated adiabatic QM/MM results. Obviously, such a validation is much more meaningful than the scientifically incorrect assertions about the alleged invalidity of our approach.

II.2 Accurate EVB Treatments of the Reaction of DhlA

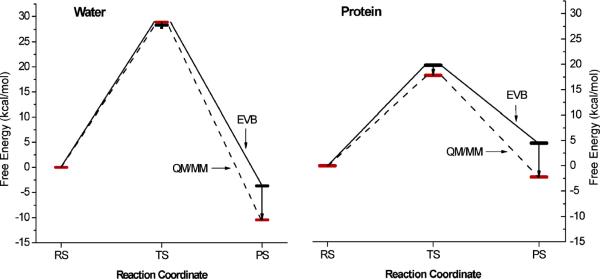

Ref. 2 focused on the gas phase reaction of DhlA, where they tried to imply that the EVB treatment of this system is, at best, simply incorrect. As stated above, the authors have not cited accurate EVB treatments of this very system in their perspective. One example is a work that used EVB to successfully resolve the highly controversial question about the energetics of the reaction in solution29. This study actually indicated that our EVB estimate of the catalytic effect and the effect of the enzyme are quantitatively correct. Trying to cast doubt on the conclusions of Refs. 29 and 17 based on irrelevant gas phase analyses (the gas phase energy cancels out in the difference between the enzymatic and solution barriers) is problematic, especially by workers that have not examined the ab initio free energy surface in the enzyme and in solution. To further illustrate the above point, we provide the results of the study of Ref. 24 in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

QM/MM activation free energies obtained by moving from the EVB to the QM/MM surfaces. This figure was originally presented in Ref. 24.

II.3 The MCMM and the Electrostatically Embedded MCMM

In view of the proliferation of the use of the EVB, and its reincarnation as seemingly different approaches, it is instructive to discuss the recent attempts of Truhlar and coworkers3-5 to capture the physics of the EVB approach under a new name. This was initially started with gas-phase studies3,5 under the name “Multi Configurational Molecular Mechanics” (MCMM), which is effectively an identical approach to the EVB, as has already been discussed in Refs. 1,6. The more recent attempt to extend the EVB to studies in solution4 under the name “electrostatically embedded MCMM based on the combined density functional and molecular mechanical method”4 is more problematic, because it may come across to the reader as being a novel innovation. However, the electrostatically embedded MCMM (which we refer to here as the EE-MCMM(EVB)), is basically identical to regular EVB. In fact, there is only one minor modification, which is unfortunately in itself problematic (except for cases where it has negligible effect). That is, this method has the same diagonal EVB elements ε1 and ε2 (called V11 and V22 in Ref. 4), and the same crucial embedding by adding the interaction of the diabatic charges with the solvent potential to ε1 and ε2 as in the original EVB, and the ground state energy (Eg) is again obtained by mixing the effective off diagonal terms from Eq. 1 above. That is, the EE-MCMM(EVB) uses the Hamiltonian:

| (2) |

whereas the original EVB uses the identical expression:

| (3) |

Now the diagonal energies of the EE-MCMM are given by:

| (4) |

Here, Qi is the vector of the residual charges in the ith diabatic state and ΔΦ is the vector of the potential on the solute atoms. Viiind (this term is formally equivalent to the last two terms of Eq. 21 of Ref. 4) is the effect of polarizing the solute diabatic charges. The EVB uses (see Eq. 2.25 in Ref. 27):

| (5) |

where U is the potential on the solute atoms and where the inductive effect of Eq. (4) is sometimes included in the EVB treatment (εiind of Eq. 5). Thus, the solvent is incorporated into the EE-MCMM diagonal elements in the same way as is done by the standard EVB treatment. Even the addition of the solute polarization in the MCMM states has long been implemented in some EVB studies. In fact, our εiind has been treated more consistently than in the treatment of in Ref. 4, being evaluated consistently (see Eq. 7 of Ref. 26) with the effect of the solvent permanent and induced dipoles included (which are not yet considered by the EE-MCMM), and not by trying to do so by an expansion treatment that might or might not provide correct results.

The solute diabatic charges are evaluated by DFT in the gas-phase exactly as in the EVB, and thus, the impression of combining DFT and MCMM may be misleading, as it gives the impression that this is a novel QM/MM approach (the issue of H12 is dealt with separately below). The implementation in Ref. 4 evaluates the potential from the solvent by an integral equation rather than by a microscopic MM treatment, but, obviously, the application of this approach to enzymes will require moving back to the microscopic electrostatic treatment of the EVB.

Additionally, the off-diagonal element of the EE-MCMM is not written explicitly in Ref. 4, and we are told4 in the text that H12 (V12) is based on the Shepard interpolation scheme, where it is really based on the EVB equation (Eq. 1), a fact which the authors do not explicitly mention. Of course, many interpolation approaches could be used to fit to the ab initio and some of them could be more effective where all the discussion is about the technical interpolation, which whether intentional or not has the effect of drawing attention away from the basic EVB treatment. At any rate it is stated that V12 is evaluated as in Ref. 5, which uses precisely the EVB equation (Eq. 1) above. Now the aim of all this is to show a new approach to obtain energy surfaces in aqueous solution with electronic structure information obtained entirely in the gas phase using a solvent dependent V, based on the gas phase charges4:

| (6) |

However, this expansion treatment does not provide a quantitative way of obtaining the solvated V12 or the solvate ground state. That is, if the expansion treatment of Ref. 4 was able to reproduce a correct description of the ground state adiabatic surface in solution, there would be no need for any EVB treatment or any diabatic Vii, and the expansion would have provided the long awaited solution to the general QM/MM-FEP problem by gas-phase expansion so that no one would need an EVB type formulation. Regarding the problems with evaluating Vg (and thus H12) by the expansion approach, we can return to our standard example of SN1 reactions10,27. In this case, the gas phase system in the large separation range is a bi-radical, with zero charge on the separated atoms. The first term in the expansion will be zero since this term is the gas phase charge, thus, the expansion will give zero solvent effect on Vg (in contrast to the enormous effect obtained with the correct solvation treatment). In fact, the success of the approach of Ref. 4 in the case of SN2 reactions is to be expected, since even the full gas phase charge distribution (in the Jorgensen's QM-FE treatments) gives reasonable results40. However, the same results would be obtained with the EVB and constant H12, and this type of EVB also works extremely well in the case of SN2 reactions27,41.

It may still be argued that the EE-MCMM is different to the EVB since the H12 term is solvent dependent in the EE-MCMM. However the correct H12 is almost solvent independent, as was initially assumed in the EVB and established in our recent studies7 and those of others42. In fact, the result reported in Fig. 9 of Ref. 4 show a solvent independent H12 in solution using the solvated diagonal elements and the expansion of Vg by applying the EVB relationship of Eq 1. This approach only gives reasonable results because the use of a solvated Hii makes H12 solvent independent. In fact, the solvated ground state surface, Vg, used to evaluate H12 (in the specialized treatment of Ref. 4) would strongly depend on the solvent in challenging charge separation reactions, which are very different from the trivial SN2 case studied in Ref. 4, and this dependence could not be represented by a simple expansion (see below). However, once the basic and crucial embedding idea of the EVB is adopted, the off-diagonal term becomes more or less solvent independent, and any treatment that tries to asses its solvent dependence will look reasonable.

In summary, the EE-MCMM method is practically identical to the EVB approach (once H12 is taken to be solvent independent), and the attempt to add solvent dependence is in itself problematic as was discussed above. Thus, the consistent embedding is entirely due to the effect of the solvent on the diagonal EVB elements. The argument that we have a new method here is particularly concerning when it is presented as the development of a “novel approach” that can be used for studies of enzymatic reactions.

II.4 Discrediting the EVB Surface without Using the Same Parameters or the Same Computer Program is Ethically Questionable Practice

As stated in section I, the effort to discredit the EVB begins in earnest with an attempt to generate the corresponding gas phase surface without actually validating the similarity between the models used here and the one that was used in Ref. 17. Such a validation should start by using the same program (which is easily available and would have been to the authors had they actually asked for it), or by trying to reproduce the reported solution profile (which would require familiarity with the corresponding mapping) to verify that the correct original models are being used, before progressing to one's own code. This is crucial, in particular when one is trying to discredit a given model without consulting the main author. Here, we should note that our concern is not that our approach was reported to give poor results. Comparing different approaches and demonstrating that one does not perform as well as other presented models does not suggest that the authors are trying to discredit a given approach. However, when the poor results have been obtained by using incorrect parameters and an error that would be very easy to validate and check for, but the senior corresponding author of the original work is never contacted to discuss this problem, then it becomes highly questionable whether the aim was anything but to discredit that model. As expected, we find major problems with the presumed reproduction of our gas phase EVB surface. In Fig. 5 of Ref. 2, the authors show three ground-state adiabatic potential surfaces for comparison. The first two are both generated using ab initio, whereas the third is stated to be generated using our EVB approach. In the first two cases (ab initio), the authors show surfaces corresponding to an SN2 reaction, with the reactant, product and transition states being clearly defined. However, the EVB surface that they present is, for lack of a better word very vague, in that is hard to discern a clear distinction between the reactant and transition states, and they appear to have a very low barrier of ~2-3 kcal/mol as opposed to the much higher barrier of ~14-19 kcal/mol they obtain with various ab initio approaches.

Figure 5.

Contour plot of the ground-state adiabatic potential surfaces obtained by (a) EVB with a gas-phase shift of -23, (b) EVB with a gas-phase shift of +23.4 and (c) ab initio (B3LYP/6-311++G**). The reaction has been defined in terms of C-O (x-axis) and C-Cl (y-axis) distances. All energies are given relative to that of the reactant state, and all energies are given in kcal/mol.

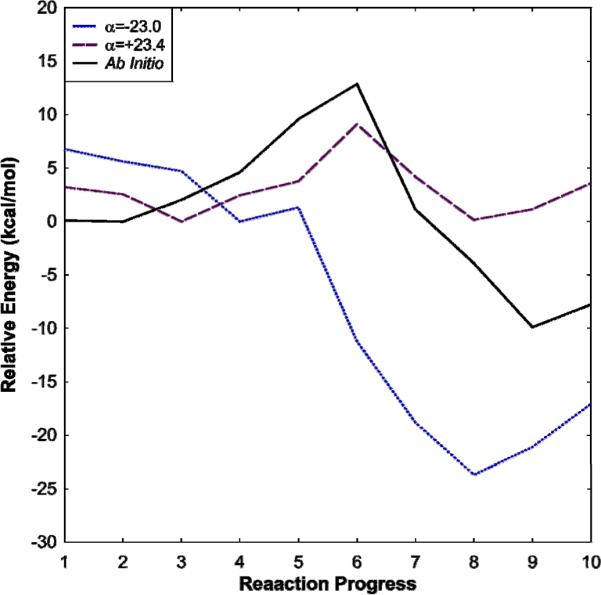

In an attempt to understand what misunderstanding led the authors of Ref. 2 to obtain such a poor result, we have evaluated the adiabatic potential energy (rather than the usual free energy) surface using our own MOLARIS18 software package. We have obtained our EVB free energy surfaces using two different gas-phase shifts (α=-23.0 and +23.4), and the corresponding surfaces are shown in Figs. 5a and b (as stated earlier in this work, this is a very small system so the surfaces can be obtained within a matter of hours). Additionally, for comparison, we have evaluated the ab initio gas phase energy surface using the B3LYP density functional which is shown in Fig. 5c. Finally, Fig. 6 shows a comparison of reaction progress along the ground state adiabatic potential energy profiles obtained by ab initio, and EVB using the different gas-phase shifts.

Figure 6.

Ground-state adiabatic potential energy profiles along the reaction coordinate obtained by (a) EVB, with a gas-phase shift of -23.0 (solid line), EVB with a gas-phase shift of +23.4 (dashed) and (c) B3LYP (dotted line). In each case, all energies are shown in kcal/mol relative to the ground state.

From Fig. 5a, it can be seen that when we use an incorrect gas phase shift without thorough mapping (i.e. mapping in all directions both backwards and forward to check for hysteresis and other potential problems, and by using careful reaction coordinate pushing), we obtain a very bad EVB surface that is qualitatively very similar to that presented in Ref. 2. However, when using the correct gas-phase shift and careful reaction coordinate pushing, we obtain an energy surface that shows a clear SN2 pathway, where ΔV≠ = 9 kcal/mol (the energetics from all three approaches is shown in Table 1). Incidentally, this is the same gas-phase shift that was published in the supporting information of not only our Ref. 17, but also the one the authors of Ref. 2 claim to have used according to their supplementary material, making it very likely that incorrectly handling the gas-phase shift is why they obtained a surface similar to that in Fig. 5a and not that of Fig. 5b. Finally, it can be seen that we obtain good agreement between the surface obtained using the correct gas-phase shift (Fig. 5b) and that obtained using ab initio in the region pertaining to the SN2 reaction (it should be noted that B3LYP is not necessarily the ideal functional for dealing with ionic systems, but we used it for comparison to Ref. 2). In light of this, it should also be pointed out that in comparison, the MOVB results presented in Ref. 2 are actually quite poor - they give a barrier of 19.2 or 23.8 kcal/mol depending on the scheme used (which is too high for an SN2 reaction of charged species in the gas phase), and overestimate the exothermicity of the reaction by ~10 kcal/mol. Additionally, Ref. 2 does not present a 2-D ground-state adiabatic potential energy surface obtained by their MOVB, making it impossible to comment on how this would compare to e.g. the very poor EVB surface they present in their Fig. 5c.

Table 1.

A comparison of the energetics of the reaction profiles obtained by EVB with a gas-phase shift of -23.0, EVB with a gas-phase shift of +23.4 and B3LYP. All energies are given in kcal/mol.

| ΔV0 | ΔV≠ | |

|---|---|---|

| EVB, α=-23.0 | -23.7 | 1.3 |

| EVB, α=+23.4 | 0.2 | 9.0 |

| Ab Inittio | -9.9 | 12.8 |

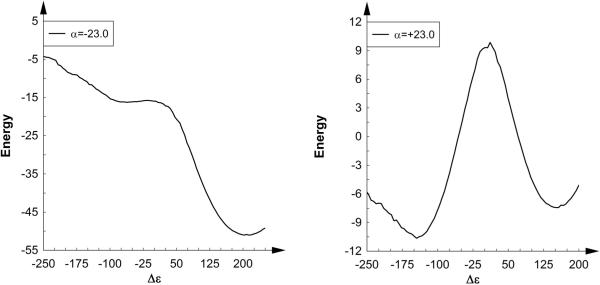

We truly hope that the authors of Ref. 2 generated their surface mistakenly due to the use of incorrect parameters or potential functions. However, this problem becomes quite serious in the case of the authors' attempt to calculate the EVB solution surface, where the authors have state that our results cannot be reproduced without ever having discussed the issue with the senior corresponding author of the manuscript. This issue will be discussed in greater detail below. In response to the allegation that our solution results are irreproducible, we have performed our EVB runs in both the gas-phase and in solution using the same parameters (i.e. those presented in the supplementary material of Ref. 17), and the corresponding energy and free energy surfaces obtained using both α = -23.0 (incorrect) and +23.4 (correct) are shown in Figs. 7 and 8 respectively. In order for our results (both in the gas-phase and in solution) to be reproducible to any interested reader, we have made all the required input files, our output files, a guest binary for the MOLARIS software package, and instructions on how to run the calculations available on our website (http://futura.usc.edu), under the section “EVB Verification”.

Figure 7.

EVB energy profiles along the reaction coordinate for the DhlA model reaction in water, obtained using gas-phase shifts of -23.0 (left) and +23.4 (right), as well as the same EVB parameters as those presented in the supplementary material of Ref. 17. All energies are shown in kcal/mol.

Figure 8.

EVB free energy profiles along the reaction coordinate for the DhlA model reaction in water, obtained using gas-phase shifts of -23.0 (left) and +23.4 (right), as well as the same EVB parameters as in the gas phase (i.e. those presented in the supplementary material of Ref. 17). All energies are shown in kcal/mol.

The most trivial and correct way to check if one reproduced someone else's force field correctly without using his program is to see if one gets the same results from a few fixed structures. We are genuinely shocked by the fact that the authors obtain results that are different from the reported results, and then claim that their results are necessarily the correct one without having done any verification. Additionally, in the field of computer simulation, it has been known that in order to reproduce the same results, it is essential to use the same algorithm. None of the authors of Ref. 2 ever approached us to request a copy of our code for the purpose of examining their statements, which would have been readily available to them had they asked for it. We have no idea how the authors have actually attempted to implement our EVB, but the idea that since a given diabatic model gives different results to that of the MOVB this automatically disqualifies that model from validity is fundamentally flawed, and we strongly believe that the basic requirement of somebody from the computational modeling community would be to ensure that they can get the same energy as the model that they are criticizing on at least one point. Finally, consider the fact that, for instance, Warshel's approach for evaluating reorganization energies is now widely accepted (e.g. Refs. 43-45, amongst others), so we do not see why this is attacked.

II.5 Parameterization to Ab Initio Surfaces

A key point, the clarification of which may confuse some readers who tend to accept the arguments brought forth by the authors of Ref. 2, is related to what the best information that should be used for the parameterization of EVB surfaces actually is. It is easy to tell those who are not familiar with the reliability of studies of enzymatic reactions that the best approach is by calibration based on gas phase ab initio results. However, such a proposition suggests inexperience in the case of the study of enzyme catalysis. That is, in our extensive experience of actually doing such calculations, we have realized that the best way to parameterize reliable EVB surfaces for studies in condensed phases is to calibrate to ab initio calculations using either implicit or explicit solvation models.

The reason for this (which was already discussed in Ref. 24) is that in the gas phase, electrostatic interactions between ionized groups lead to major polarization effects that are difficult to quantify (even when using large basis sets), and are also hard to parameterize. On the other hand, in solution, these interactions are strongly screened (this occurs both in proteins and in solution), and thus one obtains a far more stable set of parameters as well as more stable and reliable differences between the enzymatic and solution results. We do not expect that workers who are only familiar with gas phase calculations will instantly follow our point, but we do on the other hand believe that any one who will be involved in refining EVB surfaces will eventually appreciate the point we are trying to make. Similarly, it should be noted that other major force fields such as CHARMM are not validated at random, but rather by comparison to ab initio calculations49. However, even here there are differences. For instance, in the case of optimizing Van der Waals (VdW) parameters, it has been suggested to reproduce these parameters by using ab intio calculations to reproduce the electron distribution around a molecule49, whereas a much simpler and far more accurate approach is to refine the VdW parameters in such a way as to accurately reproduce the solvation free energies obtained by the model used, as was done by us since 197950, and by others51.

It is useful to note that the key unresolved issue in the study of DhlA has been the barrier height in water29. When examining this issue we of course tried to consider ab initio calculations, but found out that we are dealing with the very challenging issue of the energetics of negative ions, and decided to first try to look for relevant experimental information. We used a careful analysis of LFER results (see the discussion in footnote 68 in Ref. 29). Subsequently24, we were the only group to perform a quantitative ab initio FEP calculation on this system, and established the fact that our previous estimates were indeed accurate. Finally, we have already conducted a very careful gas phase study of precisely the dehalogenase (DhlA) system that is addressed by Ref. 2 and the results have been presented in Ref. 29.

II.6 Solvation Energy, Energy Gap, Reorganization Energy and Free Energy Surfaces in Solution

We find worth noting that the authors of Ref. 2 have no reported experience with correctly performing the EVB mapping, and indeed provide no discussion of this issue at all in Ref. 2. The problem the authors have with understanding the EVB mapping can be established by simply considering their argument that EVB mapping does not offer any special convergence advantage relative to PMF calculations that change the solute coordinate52 (for further discussion please also see Ref. 35). Unfortunately, the corresponding analysis has not involved any attempt to compare the EVB and the PMF mapping, but instead examined the irrelevant behavior of the energy gap during PMF mapping. It is hard to realize that a mapping that takes into account changes of charges and bond lengths (as is done by the EVB) is more effective than one that only changes bond lengths without performing a comparative study. Unfortunately, it was assumed in Ref. 52 that the EVB uses the energy gap as the mapping potential. However, the EVB actually uses the energy gap as the reaction coordinate, and for the mapping it uses a superimposition of the reactant and product potentials, as shown in Eq. 7 below:

| (7) |

Here, εm is the mapping potential that keeps the reaction coordinate x in the region of x', ◊m denotes an average over an MD trajectory on this potential, β = (kBT)-1, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. If the changes in εm are sufficiently gradual, the free energy profile, Δg(x'), obtained with several values of m overlap over a range of x', and putting together the full set of Δg(x') will yield a complete free energy curve for the reaction which moves the system continuously from the charges and structure of the reactant to those of the product state, rather than using an artificial constraint on only a few bonds. Thus, it is important to realize that Ref. 52 did not examine the EVB mapping approach. One of the main issues here is the convergence time and hysteresis, and this cannot be examined without actually comparing the two approaches, as was done in several of our studies (e.g. Refs 53 and 54). Continuing to try to discredit the EVB mapping approach while attempting to adopt the EVB overlooks the fact that very serious scientists are currently using this mapping approach (see e.g. Refs. 23,31-34).

The authors also attempt to address the issue of the reorganization energy, λ. Here, they simply define the reorganization energy as “the energy difference between the product and reactant diabatic states at the reactant geometry”2, and from the discussion that follows suggest that they appear to not have a clear understanding of what the reorganization energy actually is. The reorganization energy can in fact be estimated by use of the expression:

| (8) |

where ⟨Δε⟩ is the difference between εa and εb and ⟨Δε⟩a designates average over trajectories on εa or the value obtained by evaluating the microscopic Marcus parabolas, which were evaluated professionally in our works in a way used now by all workers in the field (e.g. Refs. 23,33,34, amongst others). This has little to do with the evaluation of the energy along the least energy MOVB path used in Ref. 2. Furthermore, calculations of λ by MOVB will be meaningless since it should be defined for pure non-mixed diabatic states.

Finally, the presumed calculations of the EVB solvation energies (see Table 4 of Ref. 2) are incorrect, and have no similarity at all to the values reported in our paper29, or to the values expected from any decent solvation model. To claim that the EVB gives more solvation in the TS than in the ground state in an SN2 reaction, where this was never obtained in any EVB calculations by us or any other EVB user is quite disconcerting.

III. Concluding Remarks

As we have demonstrated here in great length, the strategy employed in Ref. 2 seems to be a combination of neglecting to alert the reader to the similarities between the MCMM approach and our original EVB approach and then trying to discredit our approach by asserting that the EVB surfaces are un-physical (even though they were obtained using an incorrect treatment). Additionally, the authors attack the diabatic EVB solvation treatment, without saying that it is being used by their own embedded MCMM, and while misrepresenting the EVB solvation results. The most worrying part in all of this is the fact that one of the authors is now starting to use the very same EVB that he presents as unreliable and invalid in in Ref. 2, albeit using a different name.

Here, the most alarming message comes through when we are told that after checking the gas phase surfaces, which are presumably wrong in our EVB, it will be possible to use the VB methods in enzymes. This is particularly concerning in light of the fact that our EVB approach has been applied effectively and quantitatively to enzymatic reactions since 1980 and has been adopted by others23,31-34 for the same purpose. Implying that the EVB was not validated is a major misinformation (the reader just has to look at Fig. 4 above or in many of our works to see that this is an untrue allegation). But what is more worrying is the strategy of trying to use the same EVB under a different name in enzymes (which is what they implied they would be proceeding to do in Ref. 2).

In summary, the MCMM approach is exactly the same as the EVB approach. In other words, the MCMM approach is not equal to the diatomic-in-molecule approach or any other method that the authors of Ref. 2 are trying to invoke, but rather, it is precisely identical to the EVB (the attempt to add solvent effects to H12 is inconsistent, and we leave it to the reader to judge the effectiveness of the new version, based on the discussion in this work). Additionally, the embedded MCMM approach is practically identical to the solvated EVB. It is unfortunate that the authors try here to discredit our results when they are using an incorrect gas phase shift and poor reaction coordinate mapping, as well as probably questionable charges. The diabatic EVB is now used by many major players who have all carefully established its validity (e.g. Refs. 41,55). Finally, the authors are optimistic that their initial gas phase study in Ref. 2 will pave the way for the study of reactions in enzymes. We would like to point that we have already studied not only the model reaction in solution, but also the DhlA reaction itself by means of ab initio QM/MM with extensive configurational sampling using the EVB as a reference potential24, with highly promising results. No similar study has been ever done by any of the authors using a VB approach, nor have they evaluated the barrier in solution using hybrid QM/MM. At any rate, we are confident that the EVB will remain one of the most powerful methods for studies of enzymatic reactions.

IV. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant GM24492. All computational work was supported by the University of Southern California High Performance Computing and Communication Centre (HPCC).

V. References

- (1).Warshel A, Florian J. Empirical valence bond and related approaches. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Valero R, Song L, Gao J, Truhlar DG. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:1. doi: 10.1021/ct800318h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Albu TV, Corchado JC, Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:8465. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Higashi M, Truhlar DG. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:790. doi: 10.1021/ct800004y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kim Y, Corchado JC, Villa J, Xing J, Truhlar DG. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;112:2718. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Florian J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:5046. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hong G, Rosta E, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:19570. doi: 10.1021/jp0625199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kamerlin SCL, Haranczyck M, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:1253. doi: 10.1021/jp8071712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:5048. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hwang JK, King G, Creighton S, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:5297. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chang Y-T, Miller WH. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:5884. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Muller RP, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:17516. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bentzien J, Muller RP, Florian J, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:2293. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hwang JK, Chu ZT, Yadav A, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:8445. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Strajbl M, Hong G, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:13333. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Villa J, Bentzien J, Gonzalez-Lafon A, Lluch JM, Bertran J, Warshel A. J. Comp. Chem. 2000;21:607. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Shurki A, Strajbl M, Villa J, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4097. doi: 10.1021/ja012230z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lee FS, Chu ZT, Warshel A. J. Comp. Chem. 1993;14:161. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Olsson MH, Siegbahn PEM, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2820. doi: 10.1021/ja037233l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Liu H, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7852. doi: 10.1021/jp070938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Feierberg I, Luzhkov V, Aqvist J. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bjelic S, Brandsdal BO, Aqvist J. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10049. doi: 10.1021/bi801177k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hatcher E, Soudackov AV, Hammes-Schiffer S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5763. doi: 10.1021/ja039606o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rosta E, Klähn M, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:2934. doi: 10.1021/jp057109j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Warshel A, Weiss RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6218. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Warshel A, Sussman F, Hwang J-K. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;201:139. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Warshel A. Computer modeling of chemical reactions in enzymes and solutions. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Klähn M, Braund-Sand S, Rosta E, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:15645. doi: 10.1021/jp0521757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Olsson MHM, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15167. doi: 10.1021/ja047151c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Garcia-Viloca M, Truhlar DG, Gao J. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13558. doi: 10.1021/bi034824f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Watney JB, Agarwal PK, Hammes-Schiffer S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3745. doi: 10.1021/ja028487u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kuharski RA, Bader JS, Chandler D, Sprik M, Klein ML, Impey RW. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:3248. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Cascella M, Magistrato A, Tavernelli I, Carloni P, Rothlisberger U. Proc. Natl. Ada. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:19641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607890103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Blumberger J, Bernasconi L, Tavernelli I, Vuilleumier R, Sprik M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3928. doi: 10.1021/ja0390754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Liu H, Warshel A. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6011. doi: 10.1021/bi700201w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Neria E, Karplus M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;267:23. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Olsson MH, Hong G, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5025. doi: 10.1021/ja0212157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Xiang Y, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:1007. doi: 10.1021/jp076931f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wu Q, Cheng CL, Van Voorhis T. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:164119. doi: 10.1063/1.2800022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Chandrasekhar J, Jorgensen WL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3049. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kim HJ, Hynes JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10508. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lappe J, Cave RJ, Newton MD, Rostov IV. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:6610. doi: 10.1021/jp0456133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Marcus RA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;32:1111. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Mao J, Hauser K, Gunner MR. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9829. doi: 10.1021/bi027288k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Cherepanov DA, Krishtalik LI, Mulkidjanian AY. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1033. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MH. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3210. doi: 10.1021/cr0503106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Gao J. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:184. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Olsson MH, Parson WW, Warshel A. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1737. doi: 10.1021/cr040427e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).MacKerrel AD. Atomistic models and force fields. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. 1979;83:1640. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Aqvist J. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;95:4587. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Garcia-Viloca M, Truhlar DG, Gao JL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13558. doi: 10.1021/bi034824f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Muller RP, Warshel A. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99:17516. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Villa J, Warshel A. Journal Of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:7887. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Benjamin I. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:074508. doi: 10.1063/1.2970083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]