Abstract

Angiotensin II is the principle effector molecule of the renin angiotensin system (RAS). It exerts its various actions on the cardiovascular and renal system, mainly via interaction with the angiotensin II type-1 receptor (AT1R), which contributes to blood pressure regulation and development of hypertension but may also mediate effects on the immune system. Here we study the role of the RAS in myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (MOG-EAE), a model mimicking many aspects of multiple sclerosis. Quantitative RT-PCR analyses showed an up-regulation of renin, angiotensin-converting enzyme, as well as AT1R in the inflamed spinal cord and the immune system, including antigen presenting cells (APC). Treatment with the renin inhibitor aliskiren, the angiotensin II converting-enzyme inhibitor enalapril, as well as preventive or therapeutic application of the AT1R antagonist losartan, resulted in a significantly ameliorated course of MOG-EAE. Blockade of AT1R did not directly impact on T-cell responses, but significantly reduced numbers of CD11b+ or CD11c+ APC in immune organs and in the inflamed spinal cord. Additionally, AT1R blockade impaired the expression of CCL2, CCL3, and CXCL10, and reduced CCL2-induced APC migration. Our findings suggest a pivotal role of the RAS in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system and identify RAS blockade as a potential new target for multiple sclerosis therapy.

Keywords: antigen presenting cell, blood pressure, chemokine, multiple sclerosis

The renin angiotensin system (RAS) plays a major role in the cardiovascular system. Renin cleaves angiotensinogen to angiotensin I (AngI). AngI is further processed by angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE/ACE2) to different Ang cleavage products, among them angiotensin II (AngII) (1). In mice, AngII exerts its actions on the cardiovascular and renal systems, mainly via interaction with the AngII type-1a receptor (AT1aR) and type-1b receptor (AT1bR). AngII enhances the release of catecholamines from the adrenal gland and nerve terminals, increases thirst, and promotes salt retention and vasoconstriction, thus significantly contributing to the development of hypertension (2). Moreover, AngII promotes the development of atherosclerosis where the pathogenic role of AngII has been linked to the monocyte chemoattractant protein CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 (3, 4). Recently, the RAS and AngII have also been implicated in inflammatory processes. In hypertensive rats, immunosuppressive treatment protects against AngII-induced renal damage (5). Further studies in RAG-1–/– mice highlight the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of AngII-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction (6). A relevance of AngII for inflammatory responses in humans was recently shown in kidney transplant patients, where the presence of AT1R-activating antibodies is associated with allograft rejection (7).

In many clinical trials, modulators of the RAS-including ACE inhibitors or AT1R antagonists display beneficial effects in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (8), and thus are widely used in clinical practice. One such approach is the pharmacological blockade of the AT1R by losartan, which in contrast to other AT1R blockers, like telmisartan, does not display additional peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor (PPAR)γ agonistic effects (9). Here we investigate the role of the RAS during autoimmune inflammation of the CNS in the model of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (MOG-EAE), which mimics many aspects of multiple sclerosis (10). In particular, MOG-EAE is characterized by Th1 and Th17 responses, infiltration of macrophages, and a critical role of different antigen presenting cell (APC) populations, like CNS-derived dendritic cells (DCs) (11), but no relation of the inflammatory response to the blood pressure. We show that during autoimmune inflammation, the RAS is up-regulated in the immune system and exerts its functions mainly via AT1R in a blood pressure-independent manner by modulating APC populations and governing the expression of chemokines.

Results

Expression of RAS Components During MOG-EAE.

Compared to naive mice, MOG-EAE-diseased mice displayed a trend toward an increased renin activity in the serum on day 31 postimmunization (p.i.), while in the spinal cord and spleen, renin mRNA expression was significantly increased. In the serum, we could not delineate any difference in ACE activities between mice suffering from MOG-EAE (day 31 p.i.), and healthy control mice, yet there was a significant gender effect with higher ACE activities in males (Fig. S1). RT-PCR analyses of inflamed spinal cord and spleen (Fig. 1 A–D) revealed a significantly increased expression of AT1aR (up to 2-fold) and AT1bR (up to 7-fold), as well as ACE, which could be down-regulated by the AT1R blocker losartan. Upon direct comparison, expression of AT1bR in the spleen and spinal cord was 17- to 70-fold higher than the respective levels of AT1aR (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Expression of RAS components during MOG-EAE (day 31 p.i.). Induction of MOG-EAE leads to an (A) up to 2-fold increase in AT1aR expression and (B) up to 6-fold increase in AT1bR in the spinal cord, as well as to a (C) small increase in AT1aR expression and (D) significant increase in AT1bR expression in the spleen. In comparison to naive control mice, AT1aR (E) and AT1bR (F) on peritoneal macrophages derived from EAE diseased mice are both massively up-regulated, and can be down-regulated by losartan. Data are presented as relative expression with the respective gene expression in naive control mice or EAE mice set to 1 (n = 4–8 per group). n.d. = not detectable. In myeloid DCs prepared from murine bone marrow, expression of AT1aR (G) and AT1bR (H) is significantly up-regulated during differentiation in vitro from day 0 (d0), day 4 (d4), and day 7 (d7) until day 9 (d9).

Table 1.

Relation of AT1aR to AT1bR mRNA expression in the spinal cord, spleen, macrophages, T cells, and DCs in naive mice and after EAE induction with or without losartan treatment

| Ratio AT1bR/AT1aR in naive mice | Ratio AT1bR/AT1aR in MOG-EAE mice | Ratio AT1bR/AT1aR after AT1R blockade in MOG-EAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal cord | 29.4 ± 4.3 | 18.2 ± 9.2 | 48.7 ± 22.0 |

| Spleen | 16.8 ± 7.5 | 68.3 ± 35.1 | 58.6 ± 18.8 |

| Macrophages | n.d. | 1,113.8 ± 467.0 | 3,063.7 ± 855.7 |

| T cells | n.d. | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 20.5 ± 5.2 |

| DCs | 3.0 ± 0.4 | n.d. | n.d. |

Data are given as mean ± SD

We next analyzed the expression of ATR and ACE, as well as ACE2, in different immune cell subsets. In contrast to AT1bR, expression of AT1aR was not detectable in peritoneal macrophages and T cells of naive control mice, while in DCs both AT1aR and AT1bR were significantly up-regulated during DC maturation (Fig. 1 E–H and Fig. S2). Subsequently, we investigated the influence of MOG-EAE on the expression of RAS components in immune cells. On day 16 p.i., the expression of AT1aR, AT1bR, ACE, and ACE2 were significantly increased in peritoneal macrophages in comparison to healthy controls. In peritoneal macrophages from EAE mice, AT1R blockade down-regulated expression of AT1aR, but not AT1bR, ACE, or ACE2 (see Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). Additionally, we found a significant increase of AT1aR and AT1bR expression in T cells from EAE mice, while ACE and ACE2 were rather down-regulated as compared to healthy controls (see Fig. S2). All immune cell subsets including DCs displayed a predominant expression of AT1bR compared to AT1aR, which was especially evident in macrophages from EAE mice with a 3,000-fold increase (see Table 1).

Functional Role of the RAS During MOG-EAE as Revealed by Pharmacological Blockade.

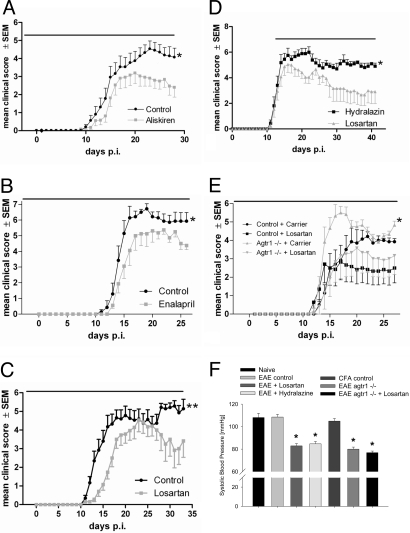

To investigate the role of renin or ACE as critical enzymes in RAS signaling pathways, we treated mice with the human renin inhibitor aliskiren (25 mg/kg body weight) (12) or the ACE inhibitor enalapril (10 mg/kg body weight). Preventive treatment with both compounds starting on day –3 p.i. significantly ameliorated the course of MOG-EAE in comparison to controls receiving carrier only (Fig. 2 A and B). To examine the receptor pathways, mice were treated with losartan, which blocks both the AT1aR and AT1bR without intrinsic PPARγ agonistic function. Preventive application of losartan in males (Fig. 2C) as well as females (Fig. S3a) significantly ameliorated the course of MOG-EAE similar to aliskiren. Losartan treatment at dosages of 30 mg/kg or 120 mg/kg body weight resulted in a later onset and a delayed maximum of disease. In the later phase of MOG-EAE, losartan-treated mice displayed a milder disease course with only tail weakness while in the control group, disability incrementally increased (Fig. S3b and see Fig. 2C) (P < 0.05). We also tested a therapeutic approach with application of losartan after the onset of MOG-EAE (day 12 p.i.). Here, the efficacy of losartan was compared to the vasodilatator hydralazine to exclude blood pressure-related effects. Both losartan and hydralazine lowered the blood pressure to a similar degree as in AT1aR knockout (agtr1–/–) mice (Fig. 2F), while only losartan significantly ameliorated the course of EAE (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Functional role of the RAS during MOG-EAE. In (A) to (E), the duration of treatment is indicated by a black bar on top of the respective graphs. (A–C) Preventive inhibition of RAS components. (A) Treatment with aliskiren (n = 22 vs. 20 mice per group, P < 0.05 on day 28 p.i., data are pooled from a total of 3 experiments), (B) enalapril (n = 7 vs. 8 mice; P < 0.05 on day 26 p.i., a representative experiment is shown), and (C) losartan (n = 19 vs. 21 mice; P < 0.01 on day 31 p.i., data are pooled from 3 independent experiments) lead to an ameliorated course of MOG-EAE. (D) Therapeutic losartan application after onset of EAE results in an ameliorated disease course. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n = 11 vs. 12 mice; P < 0.05 on day 38 p.i.). (E) Agtr1–/– mice display a more severe disease course of MOG-EAE (n = 7 wild-type and n = 6 agtr1–/– mice, P < 0.05 on day 27 p.i.). Upon treatment with losartan, there is a therapeutic effect both in wild-type and agtr1–/– mice. (F) Therapeutic efficacy of losartan in MOG-EAE is independent from the blood pressure. Application of losartan or dihydralazine in MOG-EAE leads to a similar lowered blood pressure as in agtr1–/– mice, where the effect can only slightly be extended by AT1R blockade. In contrast, immunization with MOG or CFA does not alter the blood pressure in comparison to naive control mice. Data are pooled from 4 independent experiments (n = 7 for naive mice, n = 15 for the EAE control, n = 9 for the losartan treated and n = 5 for the hydralazine treated group, n = 5 for the complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) control, n = 4 for agtr1–/– mice).

Finally, we were interested to discriminate between effects mediated via AT1aR and AT1bR and studied MOG-EAE in agtr1–/– mice. These mice express unaltered levels of AT1bR (Fig. S3c), but increased renin levels in the spinal cord and spleen (see Fig. S3 d and e). In contrast to the application of losartan and aliskiren in MOG-EAE, the disease course in agtr1–/– mice was more severe. Agtr1–/– mice displayed a paraparesis, while age- and gender-matched control mice only suffered from gait ataxia (Fig. 2E). To further confirm the pivotal role of the AT1bR as proinflammatory mediator in EAE, we treated agtr1–/– mice with losartan and observed a significant therapeutic effect (see Fig. 2E), thus speaking for the pivotal role of AT1bR as proinflammatory mediator in EAE.

Role of AT1R for APC Function in EAE.

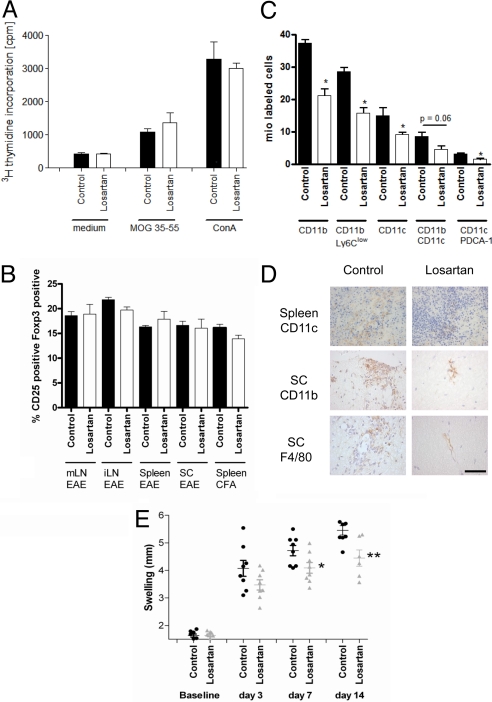

Histopathological analyses of the spinal cord after preventive blockade of AT1R by losartan revealed reduced numbers of inflammatory CD3+ T cells and Mac-3+ macrophages/microglia in losartan-treated mice on day 18 and day 31 p.i. (Table 2). Preventive application of losartan in vivo starting on day –3 p.i. did not influence ex vivo T-cell proliferation in a recall assay after stimulation with MOG or ConA (Fig. 3A). In vivo AT1R blockade did not alter expression of IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-5, IL-10, and TGF-β in supernatants from these ex vivo cultures (Fig. S4a). On day 10 p.i., frequencies of CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) in spleen, mesenteric, and inguinal lymph nodes and spinal cord were not different between losartan- and vehicle-treated mice, which was also observed after immunization with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) only (Fig. 3B). Finally, transfer of T cells from losartan- vs. vehicle-treated mice into recipients 1 day before immunization did not reveal beneficial effects on the course of MOG-EAE (Fig. S4b). Upon investigation of immune organs from losartan-treated mice, we found a significantly reduced number of splenocytes in MOG-immunized and losartan-treated mice (101 ± 11 mio; n = 8) vs. sham-treated controls (167 ± 12 mio; n = 5, P = 0.002) and mice immunized with CFA only (187 ± 14 mio; n = 9). Yet, losartan treatment did not influence numbers of annexin V or propidium iodide-positive, apoptotic or necrotic splenocytes ex vivo or after 4 or 48 h in vitro. Further FACS analyses revealed a reduction in absolute numbers of CD11b+ APC and CD11c+ APC in MOG/CFA or CFA-only immunized mice treated with losartan (Fig. 3C). In contrast, numbers of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, as well as natural killer (NK) cells and NK T cells remained unchanged (Fig. S4c). We found that losartan reduced the numbers of CD11b+ Ly6clow monocytes as well as CD11b+ CD11c+ myeloid DCs, and also CD11c+ PDCA-1+ or CD11c+ Ly6c+ plasmacytoid DCs (see Fig. 3C). Expression of MHC-II or costimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86) on macrophages was not different after AT1R blockade. We corroborated these data by immunohistochemistry for CD11b and CD11c on day 18 p.i. In comparison to vehicle-treated controls, F4/80+, CD11b+, or CD11c+ cells were reduced in the spleen and in the spinal cord of losartan-treated mice (Fig. 3D). To investigate the specificity of the findings in MOG-EAE, we investigated the delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response after injection of ovalbumin and CFA. Losartan treatment resulted in a significant reduction of foot-pad swelling (day 7 and day 14 p.i.) (Fig. 3E). In summary, these data speak for an activity of AT1R blockade in the effector stage of autoimmune inflammation.

Table 2.

Histopathological analysis of spinal cord cross-sections from losartan- (n = 4) vs. vehicle-treated mice (n = 6) on day 18 and day 31 p.i. of MOG-EAE

| Day 18 p.i. |

Day 31 p.i. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Losartan | Control | Losartan | |

| Inflammatory index | 8.4 ± 2.7 | 0.6 ± 0.6* | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2* |

| Mac-3 pos. cells/mm2 | 2042 ± 244 | 440 ± 116*** | 784 ± 93 | 502 ± 97** |

| CD-3 pos. cells/mm2 | 638 ± 54 | 91 ± 47*** | 346 ± 38 | 224 ± 44** |

P values were considered significant at *P < 0.05 and

highly significant at **P < 0.01 or

***P < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Pharmacologic blockade of AT1R in MOG-EAE targets antigen presenting cells. (A) Losartan treatment does not alter T-cell proliferation in response to MOG35–55 or ConA. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (n = 10 vs. 13 mice). (B) FACS analysis of CD25+ FoxP3+ T cells on day 10 p.i. reveals similar frequencies of CD4+ regulatory T cells in the mesenterial (mLN), inguinal lymph nodes (iLN), spleen, or spinal cord (SC) on day 10 of MOG-EAE or after immunization with CFA only. Data are pooled from 2 representative out of 4 experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (C) Upon FACS analyses of APC frequencies in the spleen on day 10 p.i., losartan treatment leads to about a 50% reduction of different APC subsets (n = 5 per group). (D) Reduction of CD11c+ DCs in the spleen and CD11b+ APC as well as F4/80+ macrophages on spinal cord cross-sections on day 18 p.i. after preventive losartan application. Representative images from the spleen and the anterior columns of the thoracolumbar spinal cord are shown. (Scale bar, 50 μm for all images.) (E) In comparison to baseline, injection of ovalbumin and CFA leads to increased foot swelling on day 7 and 14 p.i, which is significantly reduced after losartan treatment starting on day –3 p.i. (n = 8 per group).

The AT1R Exerts Effects on APC via Interference with Chemokine-Mediated Migration.

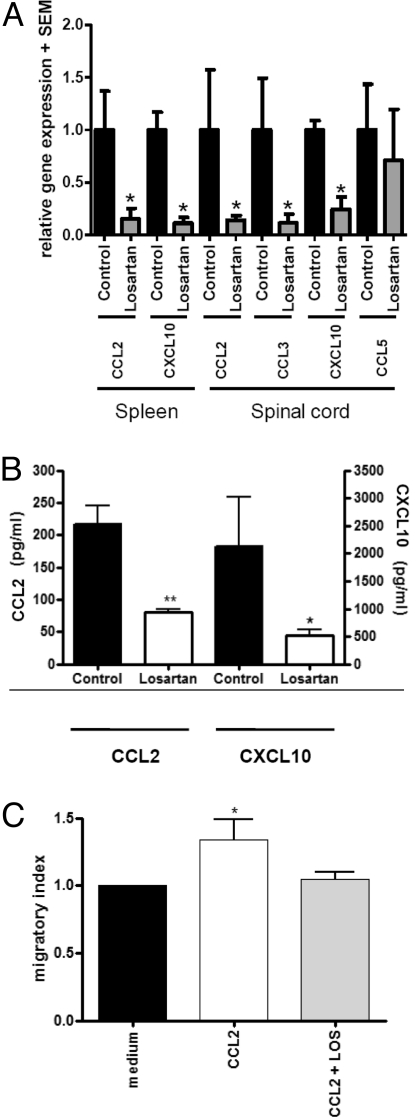

In view of the effects of AT1R blockade on the distribution of different APC subsets, we investigated the expression of chemokines. In acute (day 16 p.i.) and chronic EAE (day 31 p.i.), mRNA levels of CCL2, CCL3, and CXCL10 were significantly reduced in the spleen and inflamed spinal cord of losartan-treated mice, while the expression of CCL5 was not changed (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained upon RT-PCR analysis of macrophages (Fig. S5). In culture of peritoneal macrophages from EAE mice, protein expression of CCL2 and CXCL10 was reduced after preventive treatment with losartan in vivo (Fig. 4B). Finally, we tested the application of losartan in a macrophage chemotaxis assay in vitro. While the propensity to migrate was significantly increased upon stimulation with CCL2, this effect could be blocked after addition of losartan (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

AT1R blockade in MOG-EAE affects chemokine-induced APC migration. (A) After losartan treatment, CCL2 and CXCL10 are significantly reduced in the spleen and CCL2, CCL3, and CXCL10 are reduced in the spinal cord on day 31 p.i. of MOG-EAE. Data are presented as relative expression with the respective chemokine expression in the vehicle-treated mice set to 1 (n = 5 per group). (B) Preventive AT1R blockade until day 16 p.i. impairs CCL2 and CCL3 production in macrophages on the protein level (n = 4 vs. 3 mice per group). (C) In an ex vivo migration assay, application of CCL2 induces migration of macrophages in comparison to medium, which can be blocked by addition of losartan. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (total of 5 mice per group).

Discussion

Here we show that the RAS is expressed in the immune system during MOG-EAE, which is well in line with studies in cardiovascular disease models (6). Moreover, both blockade of the RAS by direct renin inhibition and ACE inhibition, as well as AT1R blockade, significantly ameliorate the clinical course of EAE. These data show a functional, blood pressure-independent role of the RAS in autoimmune inflammation of the CNS. Successful blockade of the RAS already at the level of renin indicates that mainly AngII and not other Ang peptides promote the pathogenesis of MOG-EAE. The clinical course of EAE after AT1R blockade implies a pivotal function of the AT1R for proinflammatory responses. The prevalence of AT1b receptors in immune cells, as well as the course of EAE in agtr1–/– mice point at the importance of AT1bR, while in the cardiovascular system and kidney, AT1aR plays a role (4). These data on the proinflammatory role of AT1bR in immune cells are well in line with a more severe interstitial fibrosis in agtr1a−/− mice (13), as well as observations on the course of autoimmune nephritis in agtr1a–/– mice (14).

While AT1R is expressed on both T cells and APC, modulation of the RAS in EAE especially affects CD11b+ as well as CD11c+ APC. In particular, blockade of AT1R interferes with migration of CD11b+ Ly6clow monocytes, but also affects different populations of CD11c+ DCs in which the importance of the RAS was highlighted in previous studies (5, 15). On the one hand, this effect on APC may decrease macrophages in the inflamed CNS. On the other hand, it also limits numbers of DCs, whose presence in the CNS is crucial for the local activation of infiltrating T cells and, thus, the initiation and progression of EAE (11). An influence of the RAS on migration of CD11b+ monocytes and DCs was also shown in models of cardiovascular disease, like atherosclerosis, where chemokines and their receptors, such as CCL2 and CCR5, may be involved (3, 16). In particular, inhibition of the RAS at the level of AngII formation or AT1R may affect adhesion of monocytes to blood vessels or migration of monocytes into atherosclerotic plaques (17). In EAE, the inhibition of APC migration may be mediated by an effect of the RAS on chemokine expression. Well in line with this observation, RAS blockade reduced the AngII-induced release of the chemokine CCL2 in monocytes in vitro and in vivo (18, 19). On a molecular level, the effects of AT1R blockade on chemokine expression may be explained by an impaired activation of NF-κB, which is a key regulator of the CCL2 gene (20). Previous studies revealed that AngII is a potent activator of NF-κB-mediated pathways in vitro and in vivo in models of cardiovascular and renal disease (21). Consequently, inhibition of NF-κB protects from AngII-induced organ damage (22). In reverse, RAS blockade may also impair NF-κB activation (18).

In addition to its effects on APC, components of the RAS may regulate T-cell functions (6, 23). Preliminary data in T cell-mediated autoimmunity already point to a role for the RAS in inflammation, and application of the ACE inhibitor captopril in EAE provided beneficial effects (24). However, ACE inhibitors do not only block AngII formation but also affect bradykinine pathways, which may also modulate autoimmunity of the CNS (25). The results in agtr1–/– mice and with the renin inhibitor aliskiren support the concept that in EAE, targeting the RAS acts via AngII-mediated pathways. While telmisartan suppresses experimental autoimmune uveitis (26), it also possesses a PPARγ agonistic effect (9), which somehow limits the specificity of this observation for the RAS. Our data extend these previous findings and definitely identify the AT1R as a pivotal RAS signaling pathway in autoimmune inflammation that is linked to APC function independent of bradykinine or PPARγ functions.

So far, clinical studies on RAS inhibition in autoimmune disease are rare (for example see ref. 27). Yet, none of the trials elucidated a mechanism showing how RAS blockade may have a beneficial effect on the outcome of these autoimmune diseases. Here, we show a pivotal role for the RAS in immune cell migration in autoimmune inflammation. These results in the animal model of EAE may well relate to multiple sclerosis, where levels of serum ACE activity were suggested as an indicator of disease activity (28). ACE inhibitors and AT1R blockers are used by millions of people worldwide for cardiovascular indications, with good tolerability; no long-term adverse effects on the immune system have been discerned so far. Thus, studies in multiple sclerosis patients with drugs targeting the RAS are highly warranted.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Harlan Winkelmann), agtr1–/– mice from Jackson Laboratories (Charles River), and kept under pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were approved by the North-Rhine-Westphalia authorities for animal experimentation.

Induction and Clinical Evaluation of EAE and DTH Assay.

On day 0 p.i., 10-week-old mice received a s.c. injection of 200 mg of MOG35-55 peptide (Charite) in CFA containing 200 mg of Mycobacteria tuberculosis [Difco/BD Biosciences(BD)]. On day 0 and day 2 p.i., 200 ng of pertussis toxin (List/Quadratec) were applied i.p. Mice were weighed and scored for clinical signs daily according to a 10-scale score (29): 0 = normal; 1 = reduced tone of tail; 2 = limp tail, impaired righting; 3 = absent righting; 4 = gait ataxia; 5 = mild paraparesis of hindlimbs; 6 = moderate paraparesis; 7 = severe paraparesis or paraplegia; 8 = tetraparesis; 9 = moribund; 10 = death. Assessment of DTH responses was performed as described in ref. 30.

Treatment with Losartan and Aliskiren.

Thirty or 120 mg/kg body weight losartan (Sigma) was given orally once a day. Twenty-five mg/kg body weight aliskiren (Novartis) was applied via s.c. implanted osmotic pumps (Alzet/Charles River). Vehicle alone was applied as a negative control.

Blood Pressure Measurements.

Systolic blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff plethysmography (BP-98A; Softron Co.). Ten measurements per mouse were recorded daily for 3 days before EAE induction and after day 28 p.i.

Immunohistochemistry.

H&E staining and immunohistochemistry were performed on 3 μm cross paraffin or cryosections, as described in ref. 29, to determine inflammatory infiltrates, T cells (Serotec), macrophages, and DCs (BD). Omitting the primary antibody served as negative control. Blinded quantification of labeled cells was performed as described (31).

Cell Culture.

Peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with IFN-γ (100 IU/ml) (Immunotools) or LPS (100 ng/ml, Sigma). Pan T cells were stimulated with α-CD3 and α-CD28, each at 1 μg/ml for 48 h. Bone marrow-derived myeloid DCs were cultured and differentiated as described in ref. 31.

Proliferation Assay.

Splenocytes (3 × 105) were stimulated with 20 μg/ml MOG35-55 peptide or 1.25 μg/ml ConA (Sigma) or medium alone as control for 48 h, followed by a 16-h pulse with 0.2 μCi 3H-thymidine (ICN). Incorporated radioactivity was measured with a Betaplate liquid scintillation counter (Perkin–Elmer).

ELISA.

Supernatants were collected after 6 h (peritoneal macrophages) or 48 h (primary splenocyte culture) and were tested for IFN-γ, TGF-β, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, CCL2, and CXCL10 expression by sandwich ELISA kits (BD and R&D Systems).

FACS Analyses.

FACS analysis was performed using a FACS Canto II (BD) and CellQuest software. Monoclonal antibodies purchased from BD were used to detect CD4, CD8a, CD3, Ly6c, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, CD80, CD86, MHC-II, NK1.1, and PDCA-1 (clone JF05–1C2.4.1, Miltenyi). For intracellular staining, the FoxP3 staining kit (eBioscience) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-PCR.

For quantification of murine CCL2, CXCL10, CCL3, CCL5, renin, AT1aR, AT1bR, ACE, and ACE2, we used predeveloped assays from Applied Biosystems with β-actin as control. All PCR reactions were performed on a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) in quadruplicates; relative quantification was performed according to Livak and Schmittgen (32).

Macrophage Migration Assay.

The chemotactic activity of peritoneal macrophages was assayed using a modified protocol as described in ref. 31, with a polycarbonate filter (pore size 5 μm). After 16 h incubation, migrated cells were counted by FACS after gating.

Statistical Analyses.

Analysis was performed using a Mann Whitney U-test for clinical courses and histological quantifications, a Kruskal-Wallis test for blood pressure, and a Student's t-test for ELISA, RT-PCR, proliferation assays, and FACS analyses (PRISM software, GraphPad). Data are given as mean values ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. P-values were considered significant at *P < 0.05 and highly significant at **P < 0.01 or ***P < 0.001.

SI.

Further methods are available in the SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Fred Lühder and Niels Kruse, Göttingen, Germany for helpful discussions; Christina Schwandt, Düsseldorf, Germany for excellent technical assistance; Prof Friedrich C. Luft, Berlin, Germany for critically reading of the manuscript, and Novartis Pharma AG, Basle, Switzerland for providing aliskiren.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903602106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goodfriend TL, Elliott ME, Catt KJ. Angiotensin receptors and their antagonists. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1649–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606203342507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowley SD, et al. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17985–17990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Combadiere C, et al. Combined inhibition of CCL2, CX3CR1, and CCR5 abrogates Ly6C(hi) and Ly6C(lo) monocytosis and almost abolishes atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:1649–1657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.745091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griendling KK, Lassegue B, Alexander RW. Angiotensin receptors and their therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:281–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller DN, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment protects against angiotensin II-induced renal damage. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1679–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzik TJ, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dragun D, et al. Angiotensin II type 1-receptor activating antibodies in renal-allograft rejection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:558–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner C, et al. RAS blockade with ARB and ACE inhibitors: current perspective on rationale and patient selection. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:418–431. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clasen R, et al. PPARgamma-activating angiotensin type-1 receptor blockers induce adiponectin. Hypertension. 2005;46:137–143. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168046.19884.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrero-Herranz E, Pardo LA, Gold R, Linker RA. Pattern of axonal injury in murine myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: implications for multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2005;11:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller DN, Derer W, Dechend R. Aliskiren—mode of action and preclinical data. J Mol Med. 2008;86:659–662. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishida M, et al. Absence of angiotensin II type 1 receptor in bone marrow-derived cells is detrimental in the evolution of renal fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1859–1868. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley SD, et al. Glomerular type 1 angiotensin receptors augment kidney injury and inflammation in murine autoimmune nephritis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:943–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI34862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahmod KA, et al. Control of dendritic cell differentiation by angiotensin II. FASEB J. 2003;17:491–493. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0755fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tacke F, et al. Monocyte subsets differentially employ CCR2, CCR5, and CX3CR1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:185–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soehnlein O, et al. ACE inhibition lowers angiotensin-II-induced monocyte adhesion to HUVEC by reduction of p65 translocation and AT 1 expression. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:399–407. doi: 10.1159/000087340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmeisser A, et al. ACE inhibition lowers angiotensin II-induced chemokine expression by reduction of NF-kappaB activity and AT1 receptor expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:532–540. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf G, Schneider A, Helmchen U, Stahl RA. AT1-receptor antagonists abolish glomerular MCP-1 expression in a model of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. Exp Nephrol. 1998;6:112–120. doi: 10.1159/000020513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueda A, Ishigatsubo Y, Okubo T, Yoshimura T. Transcriptional regulation of the human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene. Cooperation of two NF-kappaB sites and NF-kappaB/Rel subunit specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31092–31099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Ortega M, et al. Angiotensin II participates in mononuclear cell recruitment in experimental immune complex nephritis through nuclear factor-kappa B activation and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis. J Immunol. 1998;161:430–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller DN, et al. Aspirin inhibits NF-kappaB and protects from angiotensin II-induced organ damage. FASEB J. 2001;15:1822–1824. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0843fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Constantinescu CS, Ventura E, Hilliard B, Rostami A. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor captopril on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1995;17:471–491. doi: 10.3109/08923979509016382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulze-Topphoff U, et al. Activation of kinin receptor B1 limits encephalitogenic T lymphocyte recruitment to the central nervous system. Nat Med. 2009;15:788–793. doi: 10.1038/nm.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okunuki Y, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker telmisartan suppresses experimental autoimmune uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2255–2261. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin MF, et al. Captopril: a new treatment for rheumatoid arthritis? Lancet. 1984;1:1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constantinescu CS, Goodman DB, Grossman RI, Mannon LJ, Cohen JA. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:1012–1015. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550200068012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linker RA, et al. CNTF is a major protective factor in demyelinating CNS disease: a neurotrophic cytokine as modulator in neuroinflammation. Nat Med. 2002;8:620–624. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetzl EJ, et al. Enhanced delayed-type hypersensitivity and diminished immediate-type hypersensitivity in mice lacking the inducible VPAC(2) receptor for vasoactive intestinal peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13854–13859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241503798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linker RA, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor deficiency modulates the immune response and limits autoimmune demyelination: a new role for neurotrophic cytokines in neuroinflammation. J Immunol. 2008;180:2204–2213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.